∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗∗

(6/10) Sci-fi inspired melodrama with political undertones, this 1920 film is an early, but slightly clumsy, example of German expressionism. Occasionally stunning visuals and camera work are hampered by a meandering script and good performances are lost due to the lack of any character development.

Algol (Algol – Tragödie der Macht). 1920, Germany. Directed by Hans Werckmeister. Written by Hans Brennert & Friedrich Köhne. Starring: Emil Jannings, John Gottowt, Hanna Ralph, Käthe Haack, Ernst Hofman. IMDb score: 6.5. Tomatometer: N/A. Metascore: N/A.

Algol – sometimes known in English as Power – isn’t quite among the masterpieces of Weimar cinema in the 1920’s, but it is interesting for a number of reasons: it was perhaps the first serious feature-length movie about an alien visitor, and a good example of the sort of politically charged Faustian tales that were so popular in Germany during the teens and the twenties. Made in 1920, it was an early work of the highly influential German expressionism, a style that had made a huge splash just a few months earlier through director Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr Caligari.

German expressionism was born out of the strange predicament that the German film industry was in, as well as the social restlessness between the two world wars, and the rise of artistic movements such as surrealism and modernism. Having been taxed with heavy war retributions to pay, Germany was economically in a bad situation, which also hit the film industry hard. But on the other hand, the war worked as a vitamin shot for the German movie production, as the demand for domestic films skyrocketed when the government banned films from allied countries – which basically meant all major film industries except neutral Denmark. Between 1914 and 1918 the number of German movies quadrupled from 40 to 120 a year.

Not being able to produce lavish and costly sets, art directors like Walter Reimann instead turned to surrealism and symbolism, creating unrealistic and cheap but very interesting set-pieces, most notably perhaps in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, a film that is almost entirely played against obvious plywood or chipboard facades with exaggerated geometrical shapes, and furniture, objects and shadows painted on. Other features of expressionism were an abundance of darkness and shadow, skewed and innovative camera angles, exaggerated make-up and deliberate over-acting. The style proved hugely influential for both European and American film, having inspired directors from Orson Welles, James Whale and Alfred Hitchcock, through Ingmar Bergman, Francois Truffaut and John Huston to Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton. The great Hollywood explosion of Expressionism was partly due to the large influx of German film makers to the States following the rise of Hitler (perhaps mots importantly directors F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang and cinematographer Karl Freund, the latter pioneered the American gothic horror together with director Tod Browning with Dracula in 1931).

But, alas, director Hans Werckmeister was no Fritz Lang. Therefore Algol is a muddled mishmash of surrealism and realism, creating a strange juxtaposition where the Expressionist elements stand out as gaudy against the realism, and the weight of the seriousness is reduced by the exaggerated acting and symbolism of the sometimes clumsily Expressionist elements. Confusion is further added by the fact that the film promises sci-fi, but only partly delivers, then promises a social and political allegory, but fails to go the distance and settles for being something of a personal melodrama in the end.

The story in itself is fairly simple: Mine worker Robert Herne (Oscar-winner Emil Jannings) befriends a new worker (John Gottowt, who later played the van Helsing-esque professor in Nosferatu), who turns out to be Algol, an inhabitant of a planet revolving around the star Algol. The alien gives him the plans of a machine that harnesses the light of Algol, converting it into electricity. Herne uses the secret of the machine to build power plants all over the world, creating free energy, making him the most rich and powerful man in the world. But instead of using this power for good, Herne uses it to create a ruthless monopoly by first putting coal mines out of business, and then charges impossible tributes from the people for giving them use of his electricity. Coal miners who at first rejoice at the thought of being freed from the dreadful mines soon find themselves in even worse predicaments in the new factories creating products for paying off Herne.

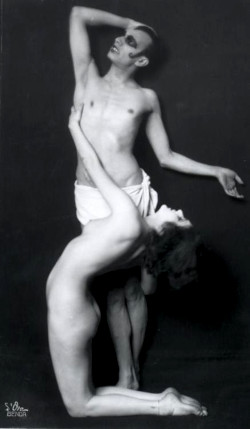

The revolutionary machine creates a catastrophic economic upheaval that in effect creates a ruling class and an underclass. Herne becomes evil and ruthless, corrupted by the power he wields, and effectively alienates his old friends and loved ones, including his girlfriend Maria Obal (Hanna Ralph, Janning’s wife at the time), who becomes a leader of he rural ”Third World”. The evil industrial conglomerate is shown in stark contrast to the family-oriented and just life of the poor agricultural workers of Obal’s country. But trouble looms when the coal runs out, Obal and her son cannot afford to pay for Herne’s ”Bio Werks” – and they plea for him to turn over the technology to the people, for the good of mankind. Herne refuses, thus finally also alienating his beloved daughter. There is also a few subplots here with Herne’s daughter (Erna Morena) and Maria Obal’s son (Hans Adalbert Schlettow), as well as Herne’s hedonistic and evil playboy son (Ernst Hofman) trying to take power for himself, but these take up a little too much of the rather long playing time of 112 minutes. Although Hofman is extremely sexy as the androgynous and hedonistic evil playboy. And we get a half naked dance routine by the young underground cult dancer Sebastian Droste, who would later create scandals with his bizarre, dark and sexual performances with fellow dancer Anita Berber.

There’s a popular uprising from the lower class, with calls to hand over the control of the Bio-Factories to the people, in socialist fashion. But this subplot sort of just teeters out and the film comes to an end with the old Herne realises his own power madness, and destroys the Bio Werks rather than pass it to his corrupted son. As is appropriate in these films, he also dies in the process. Algol the alien is seen here and there creating restlessness, but his role is really played out once he gives his machine to Herne. However, his double role as both socialist rabble-rouser and capitalist fiend is interesting, as it is one that is found in numerous German films from the era. Olaf Fønss’ Homunculus did it in Otto Rippert’s sci-fi horror film Homunculus (1916, review), and Brigitte Helm famously did the same with Maria/Maschinenmensch in Lang’s Metropolis (1927, review).

In the home country of Goethe and Wagner, Faustian themes were incredibly popular in the teens and twenties, starting with what could arguably be called the first feature-length horror film in 1913, Paul Wegener’s The Student of Prague, and continuing with dozens upon dozens of movies.

Visually the film certainly has its moments. The architecture inside Herne’s palace is heavily inspired by modernist, cubist art, and one can clearly see the influence of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. This is no surprise, as the art director Walter Reimann is the same that designed that movie. However, some of it just looks like amateur backdrops from a community theatre play – that’s when the filmmakers try to create realistic backdrops, such as the exteriors of the factory, as seen through a window, or the starry skies. The bad paintings clash wildly with the impressive architectural design. And the scale engine that Algol produces for Herne looks like something from an elementary school science project. Reimann also worked on Otto Rippert’s The Plague of Florence (1919), Henrik Galeen’s Alraune (1928, review), Ernst Lubitsch’s Eternal Love (1929) and Richard Oswald’s remake of his influential film Unheimliche Geschichten (1932).

The cinematography is partly awesome, partly workmanlike, courtesy of Danish veteran Axel Graatkjær, who honed his skills making short films in he early days of Danish cinema, and switched almost exclusively to feature films upon his move to Germany around 1915. Among his better known work is the controversial Danish film A Victim of the Mormons (1911), the first German adaptation of Bernhard Kellermann’s sci-fi novel The Tunnel (1915), and the famous 1921 adaptation of Hamlet, starring Danish superstar Asta Nielsen in the title role as a female Hamlet.

What Axel Graatkjær and Werckmeister do right is the lighting, from the pitch-black caverns of the coal mines to the brightly lit halls of Herne’s palace. However, the camera work is completely unimaginative, mostly static shots, sometimes in spaces that seem too cramped. However, Werckmeister does use a refreshing variety of wide, medium and close shots, and the editing is surprisingly advanced for 1920. There are a few visual effects, like double exposures as Algol appears and disappears, although they aren’t all that impressive, and these effects were rather old hat even at the time. The wardrobe isn’t the film’s strong point, with sometimes odd choices. The demon/alien outfit of Algol is just silly, looking like he’s about to step into a ballet in his sheer chiffon robe.

Emil Jannings is impressive as Herne, and Ernst Hofman is magnetic when he is on screen. Most actors do a decent job, but the direction is messy and as mentioned before the juxtaposition between the realistic and expressionist elements makes especially John Gottowt’s scenery-chewing overtly dramatic performance downright silly.

The film is too long (112 minutes) and there are too many subplots of marginal value to the film. Perhaps because of the fear of being labelled communists, writers Hans Brennert and Friedel Köhne (or director Werckmeister) sort of forget about the whole working class upheaval thing when it becomes time for the finale. Instead they cop out and makes the personal tragedy of Robert Herne and his power madness the tipping point of the film. Ultimately it is a misanthropic ending – nothing good can come into this world, because man ultimately will strive for his own interests and power hunger, it seems to say (man here represented by both himself and his son).

Swiss/German actor Emil Jannings had a successful and diverse career. He started out as a character actor in legendary director Max Reinhardt’s theatre company in Germany, and started acting in films in 1914. He starred in multiple films made by F.W. Murnau (of Nosferatu fame), perhaps best known for his portrayal of Mephistopheles in 1926’s Faust. In 1927-1929 he made a string of successful films in Hollywood, for Canadian Victor Fleming (The Way of All Flesh, 1927) German Ernst Lubitsch (The Patriot, 1928), Finnish Mauritz Stiller (Street of Sin, 1928) and Russian Lewis Milestone/Lev Milstein (Betrayal, 1929), among others.

Jannings was the first actor to win an Oscar, for his work in The Way of All Flesh and Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command. He is also the only actor to win a single Oscar for multiple performances. Later research has shown that he was actually the second choice of the Academy jury. The actual winner of the vote was the dog Rin Tin Tin. Fearing that the Academy would not be taken seriously – it was their first Oscar gala – they decided not to have a canine winner. But Janning’s Hollywood career was over almost as soon as it had begun – his thick German accent made him completely unintelligible in talkies, and he moved back to Germany, where he then became an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazis, appearing in many propaganda films. This fact meant his career was completely over after the fall of the Third Reich, and he retired to Austria. His home town of Rorschach, Switzerland, honoured him with their own version of Hollywood Walk of Fame star in 2004. But apparently someone hadn’t done their research, as they were not aware of his work with the Nazis. They were informed of this just hours before the ceremony, and the star was removed just a few days later.

Austrian-Hungarian John Gottowt (Algol) was a highly regarded actor and director, and appeared in the 1913 version of The Student of Prague, a story freely adapted from Edgar Allan Poe’s short story William Wilson and the German legend Faust. Prior to Algol he starred in Robert Wiene’s Genuine (1920), and later as Professor Bulwer (Abraham van Helsing renamed for copyrights reasons) in the genre-defining, but unauthorized Dracula-adaptation Nosferatu in 1922. He also appeared alongside greats as Emil Jannings, Conrad Veidt, Werner Krauss and William Dieterle in the 1924 film Waxworks (Das Wachsfigurenkabinett, 1924). Hans Adalbert Schlettow had a long and successful career, spanning nearly 40 years, and is perhaps best known for appearing in Dr. Mabuse, der Speiler (1922).

It is worth mentioning that all four female actors in the movie had long and successful careers in film and on stage, a bit unusual in a medium that often chose pretty faces for the female roles than accomplished actors. Hanna Ralph was for a time married to Emil Jannings, one of the greats of German silent cinema, and was a trusted character actress. Her film production was not extremely prolific, but when she appeared on screen it tended to be in prestigious productions. She is perhaps best known for her role as Brunhilde, one of the female leads, in Fritz Lang’s epic Die Nibelungen (1926). She also appeared in F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1924) and opposite Werner Krauss in Napoleon at St. Helena (1929). She successfully made the transition to sound, but retired from acting during WWII. She made a brief return to the screen in the fifties, and was awarded a lifetime achievement award at the German Film Awards in 1964.

Erna Morena was a tall, dark-haired actress often playing wealthy foreign femme fatales, like in Algol, or noble aristocrats. While she appeared in 120 films between 1913 and 1940, and worked with many of Germany’s top directors, she is seldom remembered today, perhaps because she somehow managed to navigate between these directors’ most famous films. She is perhaps best known for her sexual appearances in the lead of two of her early films, Lulu (1917) and Richard Oswald’s The Diary of a Lost Woman (1918). Morena also had the bad fortune to sign on for the infamous Anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda film Jud Süß (1940), and she dropped out of film acting soon after.

Gertrude Welcker was a renowned stage actress who appeared in over 50 silent films, perhaps most notably as Countess Dusy Told in Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922).

Käthe Haack, playing Herne’s daughter Magda, was a petite blonde beauty who had a film and TV career that spanned an astounding 70 years. She started her career as a teenager, and made her first film appearance as an 18-year old in 1915, and made her last TV appearance in the veterinarian sitcom Ein Heim für Tiere in 1985, a year before her death at 88 years old. Even though she remained true to the stage for all of her life, she had the time to make over 250 film or TV appearances. Best known are probably her roles in the hugely expensive 1941 adaptation of Münhchausen, starring megastar Hans Albers, her role as Emil’s mother the 1931 children’s film Emil und die Detektive, and in Hedda Gabler (1925), starring Asta Nielsen. Despite working in Germany through the war, Haack was able to avoid the most egregious propaganda films and too close an entanglement with the Nazi party, even though she seems to have been slapped with a two-year ban from the film industry between 1945 and 1947, as were many actors who appeared in wartime Nazi movies. This did not affect her career nor reputation much, though, and in 1973 she was also awarded a lifetime achievement award at the German Film Awards.

Dancer Sebastian Droste only appears in a short segment in the film, but it is notable as it may well be the only existing footage of him – at least publicly available. Droste (born Hugo Knobloch) appears as an enigmatic, sexual cult leader in an orgy-like dance scene in Herne’s palace, half naked. He was at the time an up an coming dancer with a very bizarre routine flavoured by sex, death and drugs. He quickly became an underground cult figure and a gay icon. He rose to prominence after he (allegedly) married fellow dancer and cocaine addict Anita Berber in 1923 and together they created a touring routine called Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase (Dances of sin, horror and ecstasy). The show was a scandal throughout Europe, and both dancers rose to temporary, but at least for Droste, fleeting, fame.

In 1925 he stole some furs and jewellery from Berber and moved to New York, where he met photographer Francis Bruguiere, who took a series of stunning photographed of him, which she titled The Way. They were to be promotional shots for an upcoming German expressionist film starring Droste – but unfortunately the film studio UFA ultimately scrapped the idea. He also wrote expressionist prose, regarded as derivative and clumsy. In New York he soon became ill with tuberculosis, and moved home to his parents in Hamburg, where he died in 1927. Some commentators have drawn parallels between Droste and film director Ed Wood, both men with huge ambitions, burning passion and unique visions, but ultimately hampered by a lack of talent. Although this comparison may not really be fair towards Droste, he was and remains in the shadow of the much more successful Berber.

All in all, one could say that Algol is a bold undertaking that foreshadows Fritz Lang’s and Thea von Harbou’s epic Metropolis, and must certainly have inspired it. However, Harbou was a much better writer than Brennert and Köhne, and the script is perhaps the biggest stumbling block of Algol. Granted, the task of describing the rise and fall of a business tycoon over the span of several decades is “cyclopean”, as H.P. Lovecraft would put it. Herne’s arc is is rather believable, partly because he is no sympathetic character to begin with, and it is easy to imagine that ones he gets his power, he clings to it – in the end even to his grave, as he would not share it even with his children. But then there are a bit too many strands of the story spiralling out in all directions, with too many characters that are left rather under-developed for us to care much about them.

Another problem is that the film lacks a clear central character. On the surface it is Robert Herne, but he is too much of an unsympathetic villain for the purpose, and about a third into the film he simply becomes the passive wall against which the rest of the characters are smashing their heads. Reginald Herne, the son, is clearly a spoiled money-grabber from the beginning and remains such throughout the movie, which is too bad, since it is a character that could have been interesting, had it been allowed a proper arc and perhaps a hero mantle. Maria Obal is a central character, but vanishes into the role of old and wise mother too soon, sitting on her farm speaking truths. The proper hero of the film is Peter Hell’s son, who is basically the same character as Peter Hell, and enters the film half-way through. But he remains anonymous, and while there’s nothing particularly wrong with Hans Adalbert Schlettow’s performance, he’s just simply too bland for us to really take notice. Which leaves Reginald’s rich muse and femme fatale Yella Ward, superbly played by Erna Morena, and Herne’s daughter Magda, in a sympathetic and delicate portrayal by Käthe Haack. Yella Ward is clearly a villain from the start, manipulating Reginald to betray his father, but Magda could very well have been allowed a more central and active role. She is set up as the conscience of the family but like most other characters has no real character arc, and because of her sex she is denied the role as a pivotal actor in the drama, as so often is the case. Oh, and I almost forgot about coal mine inheritor and Robert Herne’s wife Leonore Nissen (Gertude Welcker), but that’s just because her role in the film simply ends with her marrying Herne, after which she just sort of tags along.

Algol himself plays surprisingly little importance in the movie after he hands over the secret of the machine to Herne, and has no relevance whatsoever to the climax of the film. He just sort of lurks around on the fringes of the movie without any seeming motivation or stakes, severely deflating the Faustian premise that’s built up in the beginning.

The script builds up to a political showdown, but despite talk of workers rising up against Herne, and repeated pleas from several characters to “hand over the power to the people”, the screenwriters seem oddly disinterested in the politics of the theme, and the issue is never addressed properly. Brennert and Köhne early on dismiss the social democratic notion of capitalists and workers meeting half-way through the failure of of Leonore Nissen. Clearly their sympathies are with the workers, but they simply leave the issue hanging as the film develops into a rather bland moral tale about the corruption of power.

As my countryman Antti Alanen puts it: “Kein Meisterwerk von Werckmeister, but a fascinating and memorable contribution to Weimar cinema and the great legacy of German film fantasy”. The film is “most definitely an experience”, according to Paul Joyce, and I tend to agree, however I don’t share his unbridled enthusiasm over it, and I seem to echo the sentiment of a majority of reviewers in my opinion that the film is impressive but problematic. Looking at concept art for the movie, it seems that Werckmeister and Reimann were gunning for something like the opulence later seen in Metropolis for the modern city and factories, but simply seem to have run out of budget and time, and we never really get to see any of the planned exteriors, other than that painfully bad matte painting in one scene.

Algol has been somewhat overlooked in writing the history of Weimar cinema, probably partly because it was overshadowed by some of the greatest films made in history, and partly because it was lost for decades, and was restored in the 2000s by the legendary Stefan Drössler, and screened at MoMA in 2010. Despite its flaws Algol is not to be overlooked by by friends of German Expressionism or indeed science fiction movies. A bit too long, a bit bland as far as storytelling and intellectual substance goes, but a wild visual ride of Wagnerian scale, and an important precursor to movies like Aelita (1924, review) and Metropolis.

Janne Wass

Algol (Algol – Tragödie der Macht). 1920, Germany. Directed by Hans Werckmeister. Written by Hans Brennert & Friedrich Köhne. Starring: Emil Jannings, John Gottowt, Hanna Ralph, Käthe Haack, Hans Adalbert Schletto, Erna Morena, Gertrude Welcker, Ernst Hofman, Sebastian Droste. Cinematography: Axel Graatkjær, Hermann Kircheldorff. Art direction: Walter Reimann, Paul Scheerbart. Produced for Deutsche Lichtbild-Gesellschaft.

Leave a reply to Janne Wass Cancel reply