In 1945 the world still had time for one decent old-school mad scientist film before the genre imploded on itself. Swedish heart-throb Nils Asther shines in a Dorian Gray-inspired major studio production by Paramount about a 120 year old genius searching for the secret of everlasting life, while telling everyone around him that he is only 35. 6/10

The Man in Half Moon Street. 1945, USA. Directed by Ralph Murphy. Written by Garrett Fort & Charles Kenyon. Based on play by Barré Lyndon. Starring: Nils Asther, Helen Walker, Reinhold Schünzel, Paul Canavagh, Edmund Breon, Morton Lowry. Produced by Walter MacEwen. IMDb: 6.3/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Dr. Julian Karell is dead: to begin with. At least that is the assumption we are supposed to make from the cavalcade of talking heads in the beginning of The Man in Half Moon Street answering the question from an off-screen interviewer; “What kind of man was Julian Karell?” The answer, as is prone to be the case in mad scientist films, range from madman to genius.

After this not-so-subtle introduction we meet Dr. Karell himself (Nils Asther), by all accounts a modern Leonardo Da Vinci, and his fiancée to be, Eve Brandon (Helen Walker), daughter of the wealthy Sir Humphrey Brandon (Edmund Breon), in the latter’s sprawling London estate. We are here for a cocktail party on the occasion of the unveiling of a portrait of Ms. Brandon, which, naturally, Dr. Karell has painted. The fact that one of the guests says he could swear that the painting was done by an artist active in the 19th century is but one of the many not-so-subtle hints dropped during the first scene of the movie that makes it more than clear for the audience that Dr. Karell is a good deal older than he lets on. (At one point in the film he says he is 35, which is stretching it for a 48-year old actor, even one as well preserved as Nils Asther.)

Here begins our story about Dr. Karell, who has an apartment and a medical lab in London’s Half Moon Street. In short, Dr. Karell is actually 120 years old, but has preserved his youth thanks to a marvellous breakthrough in medical science he made with his colleague, Dr. Kurt van Bruecken (Reinhold Schünzel) at the end of the 19th century. While never explained in length, it apparently has something to do with transplanting some glands from another man into his own body, in combination with drinking some radioactive potion over the years. At this point in his life he needs another glandular transplant, and his now aged friend Dr. Bruecken has come to assist him in his task – and Karell has recruited a suicidal young man (Morton Lowry) to become organ donor – without telling him (or the audience) that the operation will lead to his death.

But things become complicated when Sir Brandon, who is suspicious of his daughter’s suitor, seeks out his friends at the Scotland Yard when Karell finally asks for Eve’s hand in marriage, asking them to check into Karell’s past. With some help from a friend (Paul Cavanagh), he manages to get Karell’s fingerprints to the police, who are perplexed by the fact that they match fingerprints found at the scene of six murders committed 60 years ago. And catching wind of the fact that his six previous test subjects died on the operating table, Karell’s young guinea pig unsurprisingly has second thoughts about going through with the project. And when Karell makes it clear that he has no qualms about stepping over a few dead bodies for his rejuvenation, his old friend van Bruecken also wants to call it all off, going as far as breaking the beaker holding the radioactive fluid that’s been halting Karell’s ageing. Plus, Karell also faces a few moral dilemmas regarding his potential marriage: To tell Eve he is 120 years old before or after? And as for a larger question: Can he live a life of eternal youth while watching his beloved wife fading before his eyes as the years pass, only to be left to face eternity alone? But of course, his most pressing problem is escaping the clutches of the Scotland Yard.

The Man in Half Moon Street came at the tail end of the mad scientist craze of the thirties and forties, before it more or less passed into obscurity in the latter half of the decade. However, unlike most of the “glandular horror” films made at the time, this picture was made for major studio Paramount – albeit by their B movie unit. While I have not found any confirmation for the reason why Paramount suddenly wanted to make a mad scientist B movie, one can note that rival MGM started their prestige production of a film with a very similar theme in 1944, namely The Picture of Dorian Gray. That film hit the movie theatres in March 1945, and Paramount probably saw their chance to ride the coat-tails of the hype around the picture, and rushed The Man in Half Moon Street into theatres in January 1945.

The Man in Half Moon Street is based on a play with the same name by Barré Lyndon (pseudonym of Alfred Edgar), which premiered in 1939 at London’s New Theatre. Lyndon was journalist and short story writer before becoming a playwright. He had already had great success with his debut play The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse (1936), first in London and then for three months on Broadway with Cedric Hardwicke in the title role. The play was turned into a film in 1939, co-starring a young Humphrey Bogart, back when all he did was play heavies. While Clitterhouse didn’t enter SF mode and was more of a straightforward crime mystery, it did borrow its underlying theme, that of the good man’s fascination with the forbidden world of crime and debauchery, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 classic Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

With this in mind, it is certainly no surprise that The Man in Half Moon Street, his third play, also takes inspiration from a fin-de-siecle Gothic novel, namely Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1890). Kenneth George Godwin at Cagey Films points out that the theme of the play can also trace its roots back to the myth-enshrouded 18th century nobleman and adventurer the Count of St. Germain, who sometimes claimed to have achieved an extension of youth through alchemy (he claimed to be 500 years old). In her book The English Crime Play in the Twentieth Century, Beatrix Hesse writes that The Man in Half Moon Street did not achieve the same success as Lyndon’s first play, “and like most science fiction, it has not aged well”. Still it had a good run of 172 shows at the New London Theatre and probably remains Lyndon’s best remembered play.

I have not been able to track down a copy of the play, but according to Amnon Kabatcnik’s book Blood on the Stage, 1925–1950, “the basic theme […] was preserved, but some plot elements were changed” in the film. From the synopses I have read, there is something about Karell’s butler being a former burglar as plot point in the play, which is absent in the film, and also as far as I can tell, the ending is somewhat different. The film also goes out of his way to make Karell a more sympathetic character – in the play he is almost immediately identified as a man with little moral scruples: at one point he orchestrates a bank robbery, thus luring the unsuspecting inside man, a bank guard, to his operating table under the pretence of giving him a new face through plastic surgery. Plus, almost all the names have been changed for some reason. In the play, Karell is called Thackarey, Eve Brandon is called Elizabeth Ryan and Kurt van Bruecken is called Ludwig Weisz.

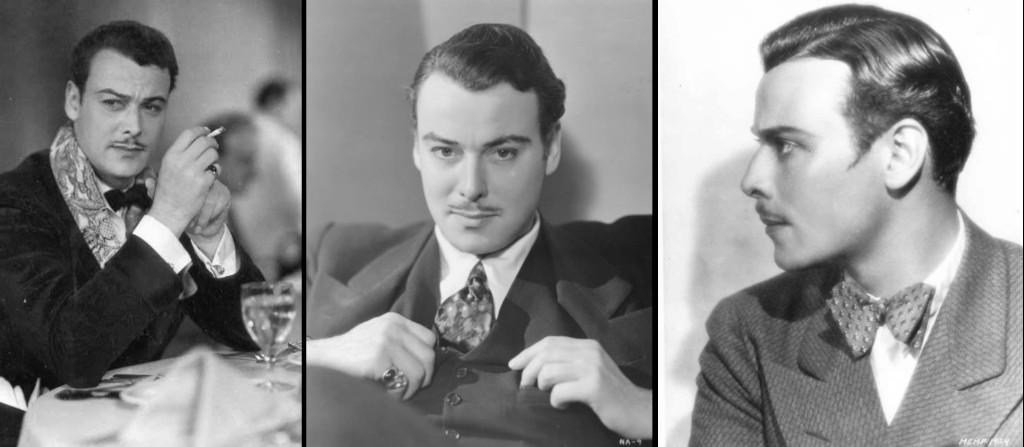

Thackaray was played, to much acclaim, by the distinguished character actor Leslie Banks, known for his gruff, often villainous portrayals, both on stage and in film. One of his most memorable roles on the screen was that of the crazed hunter Zareff in the manhunt film The Most Dangerous Game (1932). He also played the second lead in the British version of the SF movie The Tunnel (1935). Originally Alan Ladd was supposed to play Karell in the film, but Paramount finally settled on Swedish heart-throb Nils Asther.

Although produced by a major studio, The Man in Half Moon Street is decidedly a B movie made with limited resources. As almost all films made by Paramount between 1930 and 1950, the movie is imbued with the emblematic European elegance and moody chiaroscuro lighting of supervising art director Hans Dreier. However, the actual design of the film was probably left to his underling, the young Walter Tyler, who later achieved great acclaim with his designs for films like Samson and Delilah (1949), which he won an Oscar for, A Roman Holiday (1953), Sabrina (1954) and The Ten Commandments (1956). However, despite Tyler’s pedigree, there’s nothing especially memorable about the production design of The Man in Half Moon Street. Largely, one imagines, because of the constraints on time and resources, much of the film takes place in rather nondescript rooms and facades.

Much like Paramount’s earlier movies which encroached on horror and SF territory, like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review) and Island of Lost Souls (1932, review), The Man in Half Moon Street takes its subject seriously and avoids the campy low-budget feel of, for example, many of Universal’s and, naturally, low-budget efforts like PRC’s and Monogram’s mad scientist movies. It’s imbued with a certain class and solid quality running from screenplay to post-production. It’s not without its flaws, mind you, and the fact that it is based on a play is obvious from its static set-ups and talky script.

As this is a film which we are supposed to take a little bit more seriously than the Monogram mad scientist cheapos churned out in the forties, which must of course be judged by a wholly different standard, one also comes to judge its script a bit more seriously. One of the problems here is that there’s too many things going on, too many moral questions being half-heartedly probed and too many strands to the, in essence, rather simple story of a man trying to get a gland transplant in order to remain young. Dr. van Bruecken, who chose not to go through with the operation back in the 19th century, over moral qualms, is set up as Karell’s conscience, and we’re asked not only to ask ourselves if reaching for immortality is an affront to God, but also try to find in our hearts sympathy for a man who isn’t ready to tell his wife to be that he is a dried-up mummy, who kidnaps suicidal students in order to use them as raw material for his experiments and who has at least six other murders on his account. Nils Asther’s innate charm and charisma goes a long way to redeem the character in the audience’s eyes, but even so Karell cuts an unsympathetic figure. This would be fine and well if we either 1) cared about any of the other characters or 2) were given a strong psychological drama exploring the mind of a 120-year old con man. But the film fails on both accounts. The first is never even given a chance. Young Guthrie and Eve Brandon simply have too little to say and to do, and all we see of them is how they relate to Karell and his schemes. Helen Walker and Morton Lowry both do good jobs in their respective roles, but they just don’t have enough script to assist them. The script does try to confront Karell on a psychological level, but is never able to get deep enough for the movie to become anything else than a standard mad scientist plot with a glued-on psycho jargon.

One of the culprits here is the secondary plot in which Sir Brandon and the Scotland Yard are trying to figure out Karell with the aid of a Dr. Henry Latimer (Cavanagh), a character I was never quite able to place. This is a nod to the times in which the play was written, when mystery and detective plays were still all the rage both on and off Broadway. It was the sort of stuff that, even if not a major hit, was pretty sure to draw a decent crowd, in the same way that crime shows on TV tend to pull their audience today, pretty much regardless of the show’s qualities. The detective story in The Man in Half Moon Street is not handled particularly well. The previous murder sort of enter the story from out of the woods halfway through, and none of the people involved in solving the case are characters we care about or have spent any period of time following. But despite this, a lot of time is spent explaining the merits of the fingerprinting technique, pondering the ramifications of the matching prints, etcetera. These are rather dull stretches, which also take away from time we could be spending with the main characters of the movie.

As if this secondary plot was not enough, there’s also the case of the kidnapped suicide case/guinea pig locked in a room up in the attic, which is a character that we are set up top care about in the beginning, but who almost completely disappears from the film for long stretches, and ends up being little more than a plot convenience. The script further complicates matters by giving van Bruecken a trembling hand due to a stroke, which means he can’t perform the operation as planned – and yet another subplot becomes Karell trying to find a surgeon who can (and will) complete the procedure. Plus, there’s the whole romantic angle, which, naturally, is as flat as it is underused. At an hour and a half the film is simply too short to deal with all the different subplots and still have time create an emotionally gripping drama.

This said, the film’s narrowly qualities outweigh its flaws. The atmosphere is great and the acting solid, especially Asther shines, even if he is a bit of a surprise pick for the role. He carries the character’s suave, world-weary charm splendidly, and balances it well with his shrewd and calculated cold-heartedness when it comes to preserving his youth. Morton Lowry is also very good as the wide-eyed but suicidal college student, and it’s just a shame we don’t see more of him. Reinhold Schünzel cuts a sympathetic figure as the old friend of Karell’s, even if he is perhaps laying on his “frail old man” schtick a bit heavy. Helen Walker is underused but gets a chance to show off her acting chops in the end of the movie. If it seems I’m taking pot shots at the script, it’s because there’s actually enough plot here to aim at. At least the writers were attempting to do something halfway original, even if the whole thing stumbles on its own clay feet. Plus, the film has a pretty impressive, if somewhat unimaginative, score by the great Miklos Rosza.

The Man in Half Moon Street is pretty difficult to track down online, which may explain why there’s so few reviews of it out there. Still, those that are to be found are mixed to positive. Italian Kolossal a Confronto gives the movie 3/5 stars, while Richard Scheib at Moria awards it woth 2.5/5 stars. According to Scheib it “works well for the most part”, even if “Ralph Murphy’s direction is slow and talky”. Scheib also writes that “it may […] be the audience expectation of the era but one feels that the script tries to build up a mystery that is obvious from the outset – that Nils Asther has an immortality treatment”. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings gives it a positive but yet negative review writing: “there are several scenes in this movie that are individually very finely written […] What you get ultimately is a series of very nice scenes, but when you string them together, the end result is a movie that is talky and somewhat slow, and with a little too much time spent on talking about themes you take for granted in other horror movies, and not from particularly fresh angles, either. Ultimately, it may be a little too refined for its subject matter; nonetheless, if you’re interested in character, relationships, and crisp, well-written dialogue, this movie certainly has a lot to offer, though I myself find it’s a little easier to take in small doses than in one sitting.” TV Guide gives it 3/5 stars, calling it “a skillfully scripted and atypically intelligent B movie”. Not everyone is amused. D Cairns at Shadowplay writes: “watched half an hour before sinking into a coma. Will try again, using strong stimulants. Even duller than remake, The Man Who Cheated Death. Even with the lovely Helen Walker, an immortal snore.”

The special effects in the film are few and far between — the most impressive one, and this is a bit of a spoiler, is when Karell starts rapidly ageing at the end of the movie, which someone described as in “Indiana Jones style”. In a couple of shots we can see Nils Asther ageing before our eyes, without any seeming cuts, double exposures or overlays. The effect is the same one that created such a fuss in Paramount’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the studio’s makeup guru Wally Westmore who was the makeup man on that film is indeed back again in The Man in Half Moon Street. In short: As you know, colours are invisible under a matching tinted light. If you shine a red light on a white paper with a red line, in theory, the red line becomes invisible. If you remove the light, the line seems to appear out of nowhere. In black and white photography, of course, tinted lights don’t register, and you can switch between different coloured lights as long as you keep the luminosity the same. So by switching camera filters on the fly, or indeed changing the lighting on set, one could make different makeups appear or disappear with a simple change of lighting. A gradual change would make them appear slowly on the actor’s face, enhancing the eerie effect.

Much could be written about the Westmore makeup dynasty, but keeping it short here, Wally Westmore was one of the six sons of one of the early makeup pioneers in Hollywood, George Westmore. All of the six brothers followed in his footsteps, with four of them becoming chief makeup artists at four of Hollywood’s major studios. Not only did Wally work on or supervise the makeup work on a number of Hollywood’s most successful films, such as Sunset Boulevard (1950), Roman Holiday, The Ten Commandments, Vertigo (1958) and Hud (1963). He also worked on a number of high-profile (and some lesser-profiled) science fiction films. Apart from the afore-mentioned, he had a hand in, among others: Island of Lost Souls, When Worlds Collide (1951, review), The War of the Worlds (1953, review), Conquest of Space (1955, review), The Space Children (1958), Visit to a Small Planet (1960), The Nutty Professor (1963), Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964) and the legendarily bad Village of the Giants (1965).

Director Ralph Murphy and cinematographer Henry Sharp are perhaps the odd men out in an otherwise very impressive crew, being rather anonymous figures in movie history. Both were Hollywood workhorses who worked steady, but seldom on high-end productions. I can’t say which film Murphy is best known for, because he didn’t direct any well-known films. As a TV director he worked, among other things on the Lassie TV show. Without rivalry, Sharp’s greatest claim to fame is working as the cinematographer on the Marx Brothers classic Duck Soup (1933), a film that isn’t primarily remembered for its camera work. He also worked on the surprisingly good colour science fiction film Dr. Cyclops (1940, review), but the great special effects work on that one should perhaps primarily be attributed to the great Farciot Edouart. Lyndon’s play was adapted to the screen by Charles Kenyon and Garrett Fort. the latter who worked on a number of Universal’s horror movies, including Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931, review) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review).

Hungarian composer Miklos Rosza began composing music for film for his countryman Alexander Korda in London in the late thirties and soon relocated to Hollywood where he was steadily employed, and in high demand, for four decades. Rosza, with a solid classical background, had a flair for psychology and drama, and composes the music for some of Hollywood’s greatest film noirs and epics of the Golden Age. He was nominated for Oscars a dozen times, and won for Spellbound (1945), A Double Life (1947) and Ben-Hur (1959). His soundtrack for the latter film was also nominated for a Grammy. While not especially active in the field of science fiction, he did compose the theme song for the TV series Atom Squad (1953–1954), and in the latter part of his career composed music for the SF films The World, The Flesh and The Devil (1959), The Power (1968) and the H.G. Wells variation Time After Time (1979), for which he actually was awarded a Saturn Award. Ironically, this was three years after the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films had already given him a Golden Scroll lifetime achievement award.

Born in Copenhagen in 1897 to wealthy Swedish parents, Nils Asther trained as a stage actor, but quickly found himself a a movie star after Finnish-Swedish director Mauritz Stiller cast him as the lead in the lead of the poetic film The Wings in 1916 – a very early film exploring homosexuality. After a successful early career on screen in Sweden, Denmark and Germany, Asther was called up in 1926 by his old friend and, allegedly, lover, Mauritz Stiller, who had been offered a contract at MGM, and had just flown over with his young protegé Greta Garbo. At MGM the studio brass was soon impressed with Asther’s talent, but even more with his exotic allure and beauty, and he was quickly dubbed “the male Garbo” after securing his first romantic lead with the studio in 1928. After acting opposite Pola Negri and Joan Crawford, he got his final breakthrough in 1929 and 1930, with two roles playing opposite his friend Greta Garbo in Wild Orchids and The Single Standard.

The coming of sound did hurt his career somewhat, as his accent ruled him out of parts that were supposed to be American, thus ruling out the majority of male leading man roles in Hollywood. On the other hand, Asther was already known as an exotic flavour, so he didn’t suffer the the clash of expectations that befell some foreign actors. In fact, his best remembered role came in a talkie in 1932, when he played the titular General Yen opposite Barbara Stanwyck in The Bitter Tea of General Yen. He continued playing romantic leads opposite actresses like Fay Wray, Gloria Stuart and Irene Dunne and in 1934 played the lead in a romantic biopic about composer Franz Schubert.

However, despite the success, Hollywood and Asther didn’t quite get along. His homosexuality was well-known behind the scenes at MGM, and when rumours started spreading, he entered a so-called “lavender wedding” with actress Vivian Duncan, which produced a child, but ended tempestuously in 1932 after having been the fodder for many a tabloid write-up. Described as a charming but difficult man, Asther would often flout studio rules about interview embargoes and invite journalists to his home, where he gave cryptic and evasive answers about his private life, and caused the studio brass a number of headaches. His happy-go-lucky lifestyle and numerous affairs and one-night-stands didn’t help matters. And he seemed to thrive on testing the system’s limits. On the other hand, he wrote in his autobiography Nils Asther: Narrens väg – Ingen gudasaga, he was suffering from depression, panic attacks and compulsive delusions. The last drop for MGM’s manager Louis B. Mayer came in 1934 when Asther’s young Korean lover was arrested when trying to forge Asther’s signature on a cheque. According to a Mayer at boiling-point, Asther was “one of those dual-sex boys and lesbos” who needed to be driven out of Hollywood. So MGM cited a “contract breach”, which led to Asther being blacklisted for four years in Hollywood.

Asther moved to London, where he made a few of movies, the best known one probably being the historical drama Abdul the Damned (1935) and The Marriage of Corbal (1936), “a daft French Revolution Romance”, according to Nils Asther aficionado Verity Holloway, who writes that the film has a “cross-dressing love triangle at the heart of the story [which] gives the film a sexual ambiguity [that] Nils is clearly revelling [in]”. Back in Hollywood in 1938, he was no longer the marquee name he once was, but still managed to work solidly in lesser and greater roles, some of them probably a lot more fun than the stuffy leading men he did in the twenties. It didn’t hurt that much of Hollywood’s male talent was engaged in the war effort. In the forties Asther did everything from second leads in crime thrillers to character parts in romantic dramas and more far-flung roles in horror movies, like Universal’s Night Monster (1942) with both Bela Lugosi and Lionel Atwill, and Bluebeard (1944) with John Carradine. However, after the war ended, roles dried up, partly because his behaviour continued to irk studios, who, according to his memoirs, now only offered him Nazi roles. So after a good year in 1945, he packed his bags and moved to a little apartment in Philadelphia, where he took odd jobs as truck driver and mailman. According to himself, he liked the freedom of 1 dollar an hour jobs and preferred them to playing Nazis. He tried to reinvent himself as a TV guest actor in the fifties, with little success, and moved back home to Sweden in 1958. Here he did a couple of more films before retiring in 1963.

He passed away in 1981, after having worked on his posthumously released memoirs – that according to his friends were in part greatly exaggerated, in part completely made up. For SF fans Asther doesn’t have very much to offer other than The Man in Half Moon Street –– that is apart from a bit part in the pioneering Danish space fantasy A Trip to Mars (1918, review), where he plays the unlucky Martian who’s wounded by a grenade thrown by one of the barbarous Earthlings when they arrive on the planet.

Neither is there much genre fare in the career of Helen Walker, a talented actress whose career hit a speed bump, literally, in 1947. Picking up three hitch-hiking WWII veterans, she hit a divider in the road and one of her passengers died in the accident. The surviving two accused her of drunk driving and speeding. Although Walker was acquitted of all charges, her career was irreparably damaged — she continued with some success to play femme fatales, but soon found herself relegated to B movies and Poverty Row features in the fifties. Her film career ground to a halt in 1955, and she passed away from cancer in 1960, only 47 years old.

Edmund Breon, who plays Eve’s meddling father has some SF credibility, as he had an uncredited bit part in the classic The Thing from Another World (1951, review) as one of the scientists at the Arctic research station where the flying saucer is found. Paul Cavanagh was a British former barrister and royal Canadian mountie, who carved out a decent career on Broadway and in Hollywood playing British aristocrats. Interestingly enough, his only other SF role was in yet another film im which scientists dabble with eternal life. In The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957, review), he plays a villain-turned-hero as a member of a cabal that use their positions as administrators of a female prison to leech the life force out of young delinquents. I a tiny role as a trawler captain we meet again the amazing Frank Moran, whom we saw previously on this blog as the titular Ape Man in the god-awful Lugosi/Carradine movie Return of the Ape Man (1944, review). A dentist, marine veteran and prize-fighter, Moran (born 1887) fought twice for the heavyweight championship of the world, but lost both bouts. Between 1932 and 1957 he played in nearly 150 movies, often credited with roles as heavies, brawlers, henchmen and the occasional police officer. In the forties he was part of Preston Sturges’ stock company. His genre films were few and far between.

Janne Wass

The Man in Half Moon Street. 1945, USA. Directed by Ralph Murphy. Written by Garrett Fort & Charles Kenyon. Based on the play with the same name by Barré Lyndon. Starring: Nils Asther, Helen Walker, Reinhod Schünzel, Paul Canavagh, Edmund Breon, Morton Lowry, Matthew Boulton, Brandon Hurst, Frank Moran. Music: Miklós Rósza. Cinematography: Henry Sharp. Editing: Thomas Neff. Art direction: Hans Dreier, Walter Tyler. Makeup artist: Wally Westmore. Sound recordists: Ferrol Redd, Philip Wisdom. Produced by Walter MacEwen for Paramount.

Leave a comment