A doctor is wrongfully condemned to an asylum and forced to do blood research for a mad doctor. This 1958 Hammer horror knock-off written by Jimmy Sangster is entertaining in its “all but the kitchen sink” approach, but ultimately forgettable. 5/10

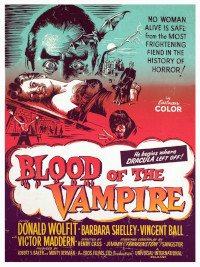

Blood of the Vampire. 1958, UK. Directed by Henry Cass. Written by Jimmy Sangster. Starring: Donald Wolfit, Vincent Ball, Barbara Shelley, Victor Maddern.. Produced by Robert Baker & Monty Berman. IMDb: 5.5/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

1874, Transylvania. In a gloomy mountenous landscape, a suspected vampire is staked and buried. However, disfigured hunchback Carl (Victor Maddern), kills the undertaker and digs up the body of his master, and retains the services of a local doctor to give his master a new heart.

So begins Blood of the Vampire, a 1958 Hammer horror clone written by Jimmy Sangster himself. Filmed in colour, it was produced by British B-movie studio Tempean Films and directed Henry Cass.

Meanwhile, in Carlstadt, young doctor John Pierre (Vincent Ball) is condemned to life in prison after being accused of murdering a patient through means of the pioneering technique of blood transfusion. He appeals to the judges to contact his mentor, Professor Meinster (Henry Vidon), who, he swears, will explain that he was trying to save is already dying patient. However, a letter from Meinster arrives saying that the Professor knows of no person called John Pierre, and that he should be condemned most harshly. While Pierre is thrown into jail, his fiancée Madeleine (Barbara Shelley) swears to seek out Meinster in order to rectify the situation.

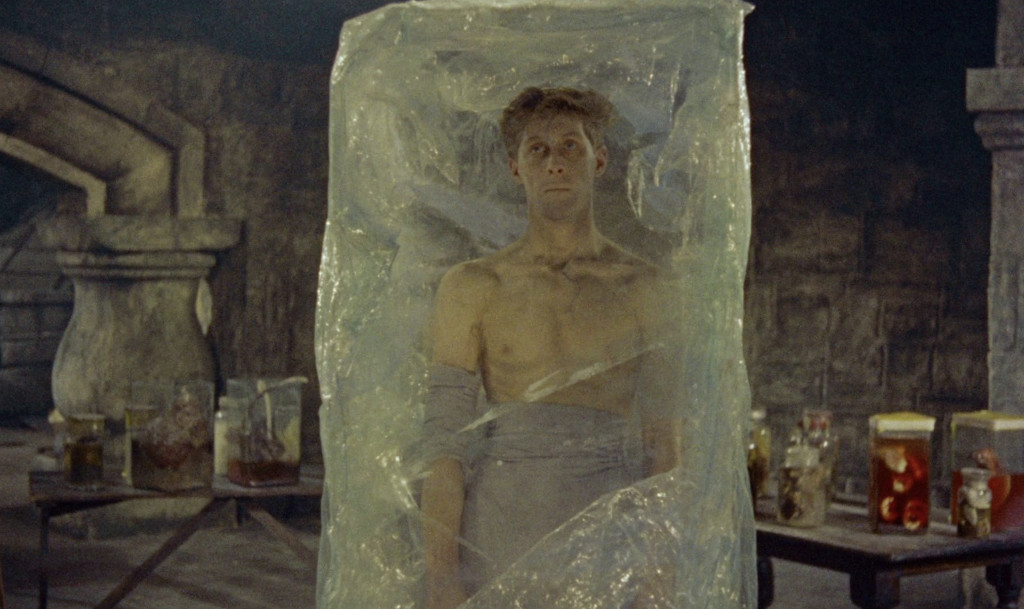

Just when Pierre is about to be shipped off to a penal colony, he is instead transferred to a prison for the criminal insane, run by a doctor called Callistratus (Donald Wolfit), who is revealed to be the same man who was previously killed on suspicions of being a vampire. Callistratus explains that he has requested the transfer of Pierre after learning of his research into blood transfusion, and wants him to assist him in finding a cure for a rare blood disease. Grudgingly, John Pierre agrees, despite his misgivings of Dr. Callistratus, stoked by the horrific stories told by his cellmate Kurt (William Devlin). Callistratus, Kurt tells him, is using inmates for gruesome experiments, killing them and draining them of blood in his secret vault below the laboratory.

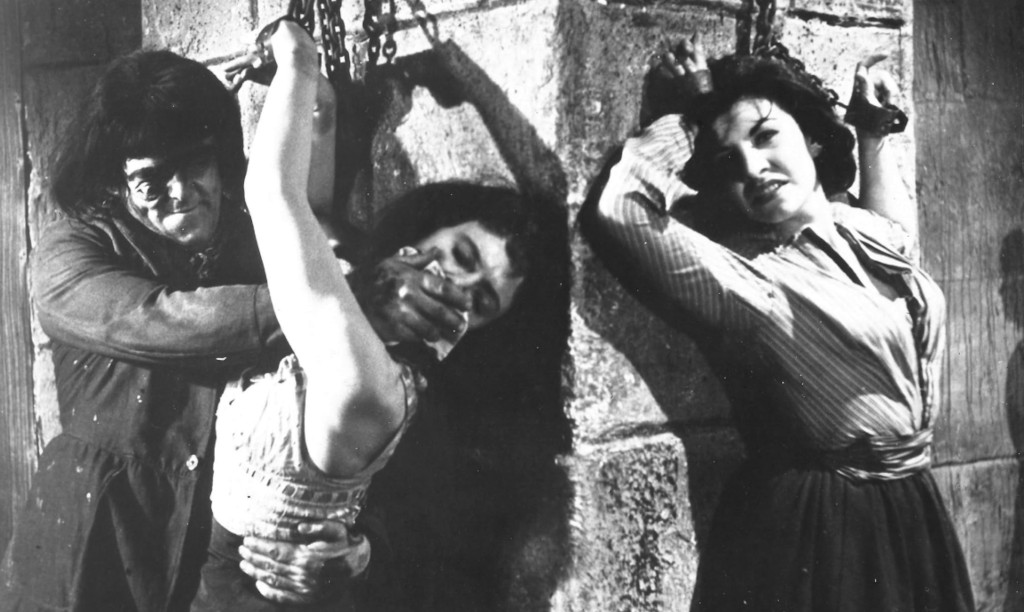

Follows now a dual storyline between Madeleine, who seeks out Meinster and tries to get Pierre released, and Pierre trying to find out what Callistratus is actually doing. Ultimately Pierre learns that Callistratus has been put to death for conducting similar research as him, and received a new heart, which has given him a blood disease because the heart comes from a man with another bloodgroup, and needs daily transfutions in order to survive. The cure he seeks is for himself. Meanwhile, Callistratus learns that Meinster has overturned Pierre’s sentence. However, he tells the authorities that Pierre has died, and tells Pierre that his case has been reviewed but that his sentence stands. Madeleine, on her hand, refuses to believe Pierre is dead, and travels to Pierre’s prison where she takes a job as a housekeeper in order to find out the truth. However, the local, corrupt chief of police (Bryan Coleman) regognises her. Meanwhile, Kurt and Pierre tries to escape, but are caught and Kurt is mangled by the guard dogs, and his body taken to Callistratus’ lab. It all culminates as our characters converge in Callistratus’ secret lab. Our heroes get some unexpected help from Carl, who refuses to obey Callistratus’ commands to strap Madeleine to the slab for blood draining. And the film ends the way you expect it to.

Background & Analysis

One can be forgiven for thinking this is a Hammer horror film. Hammer, the small British quota quickie company, had been playing around with different recipes for science fiction and horror throughout the 50s, but struck gold in 1957 their brash colour reimagining of The Curse of Frankenstein (review). The studio followed up with equally successful Dracula (retitled Horror of Dracula in the US) and The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958, review). All these were directed by Terence Fisher and written by Jimmy Sangster.

It didn’t take long for other British companies to follow suit. Amicus is the best known producer of Hammer knockoffs, but before they got off the ground, there was a small company known as Tempean Films, founded by Monty Berman and Robert Baker in 1948. The studio had predominantly focused on cheap crime films, but had already taken steps towards emulating Hammer in 1956 with the TV series The Trollenberg Terror, a Quatermass mockup, which they would eventually turn into a film in 1958 (review). In 1958, the company went straight to the source and hired Hammer’s screenwriter Jimmy Sangster to compile the screenplay of what would become their first horror movie proper, Blood of the Vampire.

[After writing the above, I watched Robin Bailes’ review of the film, and noticed he said that the film was produced by Artistes Alliance, a small company that seems to have been associated with a fellow named Ted Lloyd. There’s some confusion here, as IMDb claims Blood of the Vampire was produced for Tempean films, and has no mention of Artistes Alliance, while Letterboxd says it was produced for Artistes Alliance and has no mention of Tempean Films. Wikipedia says in its running text that the film was produced for Tempean Films, and in its fact box that it was produced for Artistes Alliance. Whatever the case, AA seems to have been a short-lived affair that produced three or four pictures in 1958 and 1959. However, Monty Berman and Robert Baker, the founders of Tempean Films, stand as producers of Blood of the Vampire, and a review in British trade magazine Monthly Film Bulletin from September, 1958 list Tempean Films as the production company. A German poster, however, mentions Artistes Alliance, while US posters and reviews only mention British distributor Eros Films, which sold the US distribution rights to Universal.]

Whatever the case with the production companies, the producers went out of teir way to our-Hammer Hammer. Even the title emulates the Hammer formula in its “X of Y” setup. The setting is the same late 19th century Europan cityscape as in Hammer’s movies, with taverns, dungeons, opulent upper-class rooms and murky labs with colourful liquids bubbling in beakers reminiscent of Hammer’s pictures, all shot in the same lush colour as Hammer’s hit films.

Jimmy Sangster has also provided a script that feels like a mashup of his previous products. The beginning draws on Dracula, complete with uneasy coach ride chauffeured by a sinister driver, to, well, essentially Castle Dracula. Here, however, Sangster mines more from Bram Stoker’s original novel than either the 1931 Universal movie or Hammer’s remake did – the entire film really mirrors Jonathan Harker’s attempts at escaping Dracula’s castle, a theme which Francis Ford Coppola exploited thoroughly in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Of course, the title is a cheat: there is no actual vampire in this film, rather a mad scientist that needs blood transfusions to survive (interestingly, the idea of curing vampirism through blood transfusion is an idea that harks back to Universal’s House of Dracula [1945, review]). The staking at the beginning of the movie feels like it’s tacked on for effect.

Instead, much of the film feels like a retread of The Revenge of Frankenstein, in which Dr. Frankenstein had set himself up as the doctor at a charity hospital for the poor and the criminal, where he pilfered body parts for his creature with the aid of a young, dashing assistant. In both movies, his victims turn on him in the end – in Blood of the Vampire, it is Kurt that ultimately sets in motion the events that lead Callistratus to be killed by his own guard dogs.

And like in The Revenge of Frankenstein, Sangster struggles to connect start and finish with a purpuseful middle. This was a trait shared by many Sangster movies. Sangster’s fortes were a good idea, intelligent treatment of themes, intriguing characters and witty dialogue. However, he often had problems with the overall dramatic arcs, leading his films to tread water in the middle. In order to kill time, his characters would often embark on some sort of quest, task or adventure that had little bearing on the actual plot, only to return to where they came from, in order to play out the finale. In The Revenge of Frankenstein, the creature escapes from his locked room and kills a girl in a park, and much time is spent on Frankenstein and the police hunting him, but we ultimately return to Frankenstein’s lab. In Blood of the Vampire much time is spent on Pierre’s and Kurt’s failed escape attempt, which never takes them any further than the prison courtyard before they are captured and returned to square one. In The Revenge of Frankenstein, we have the medical council investigating Dr. Frankenstein, which ultimately leads to his failure. In Blood of the Vampire, it is the judicial board of Carlstadt that investigates the fate of Pierre, ultimately leading to Madeleine setting out on her rescue attempt. Both films even feature a hunchback assistant called Karl.

All these intermingling stories are worthy of movies in themselves. In the beginning, there’s a feeling that you’re watching a sequel: a man researching blood diseases and is staked as a vampire! I want to see that film! A man who is staked as a vampire and is resurrected! Even better! Or a story about a scientist wrongly imprisoned in at at an institution for the criminally insane, and his struggles to escape – that’s a movie right there. How about two scientists both condemned for doing blood research? And so on and so forth.

The problem here is that Sangster just stuffs too much into the film’s 87-minute running time, as if trying to get every piece of horror cliché into the mix. As a result, we never get a chance to invest in any of the stories zipping by at lightning speed, nor do we ever get the opportunity to dig into the characters and their motivations and journeys. There’s no character arc in the film – which in and of itself is a hallmark of a Jimmy Sangster film. There’s a great opportunity here to create a battle of minds between John Pierre and Callistratus – they share a similar fate, but choose oppositely different paths to redemption. It would have been great if the film spent some time exploring the relationship between the men, letting their shared fates and their interactions shape character arcs driving the film’s plot. But Sangster gives us none of this. Callistratus is simply a villain and John Pierre simply a hero, and the two never really meet in any sort of companionship or understanding. Both Madeleine and Carl are simply plot devices and nothing more. Kurt, John Pierre’s cell mate, promises to evolve into a central character, but in a film where even the main characters remain cardboard cutouts, he has no chance of getting a leg in the door.

Furthermore, the film is completely without thematic interest. Usually, Sangster was good at developing themes thar carry his films, but that required some actual character drama. Here, where one plot twist tumbles over the previous one in rapid succession, there’s no time to delve into thematic relevance. The film wears its strory (stories) on its sleeve – what you see is what you get.

Also, it doesn’t help that the end of the movie is hilariously contrived. At one point, when John Pierre and Madeleine are chained to a pillar, John Pierre has so much slack on his chains that he has completely free movement of his arms. But when Callistratos comes to take away Madeleine to the slab John isn’t supposed to be able to reach them, so actor Vincent Ball actually has to hide the chains behind his back in order to make it seem as if he suddenly cant move his arms at all. A moment later, he again has full movement of his arms when he clunks Callistratos. And he is able to clunk Callistratos because … well, it is so contrived that it can’t even be explained shortly. See, During Kurt’s and John Pierre’s escape attempt, Kurt has been mauled by dogs, but Callistratos has kept him alive and drugged in order to keep him as a blood bag. At the climax, he rolls out the gurney upon which Kurt lies, and stops some ten feet away from where John Pierre is chained. However, with a last effort, Kurt grabs hold of Callistratos’s arm. This results in Callistratos, for some unexplicable reason, to try to back away, dragging the gurney and Kurt all the ten feet exactly to where John Pierre is chained, so that John Pierre is able to hit him over the head. Talk about sabotaging yourself!

This is not to say that this is a terrible picture by any means. On the contrary, it is very entertaining, and builds up a good deal of suspense. Because so much happens all the time, it zips along at a good pace and simply never has the opportunity to get boring.

Art director John Elphick makes the most out of the small budget, making heavy use of matte paintings in order to fill out the world and continue small sets and rooms. The matte paintings are not necessarily life-like, and one could even call them crude, but in a film like this, which already deals in a world of heightened reality, something like a delirium, the obviously painted backdrops seem oddly approriate. Director Henry Cass had no experience with horror movies (despite Wikipedia erronously labelling him as “particularly prolific in film in the horror […] genre”), but does a fair job of emulating the the Hammer look, albeit with nothing of Terence Fisher’s sophistication. Many of the scenes fall visually flat, and Elphick’s art direction does much of the work for Cass. The film has a few shock moments, such as the graphic staking in the beginning of the film, as well as the almost comically gruesome makeup for Carl (especially memorable is his one eye that seems to be in the process of escaping down his face). But all in all, it is neither more nor less gory that the Hammer movies – which weren’t really that gory to begin with.

There is also a badly photographed scene of the fictional town of Carlstadt using the miniature of London (complete with the Globe theatre) that was used in the 1944 movie Henry V.

The acting in Blood of the Vampire is, as usual in British films of the era, never worse than adequate. It is also seldom better than adequate. This has less to do with the actors than with the material they are handed. Most simply don’t get the opportunity to do anything with their superficial roles.

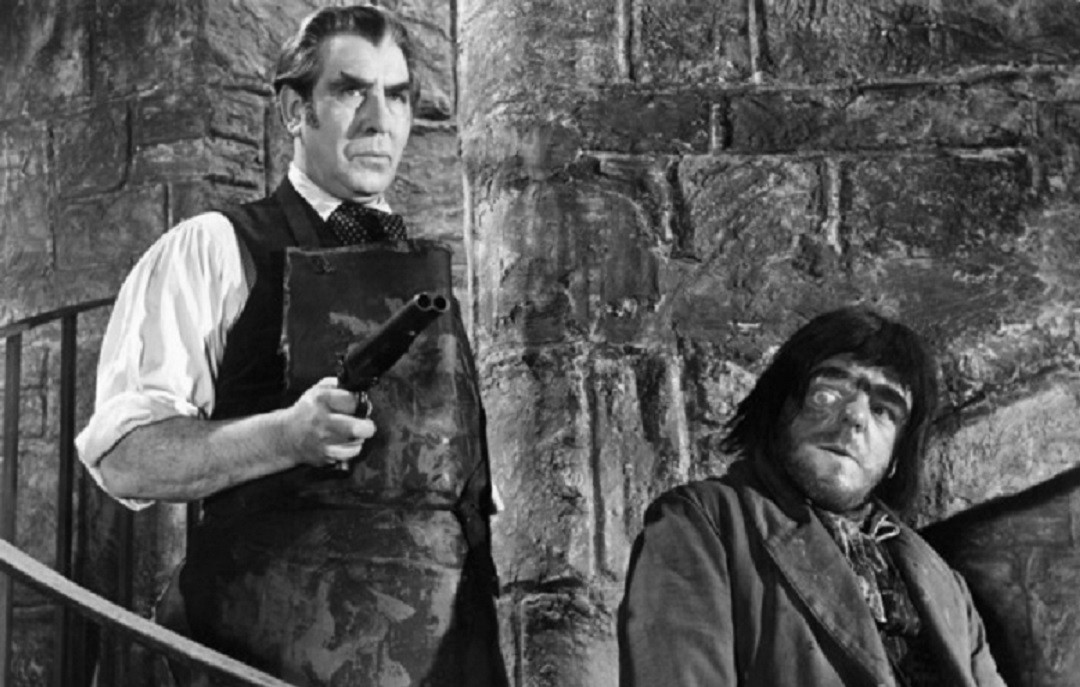

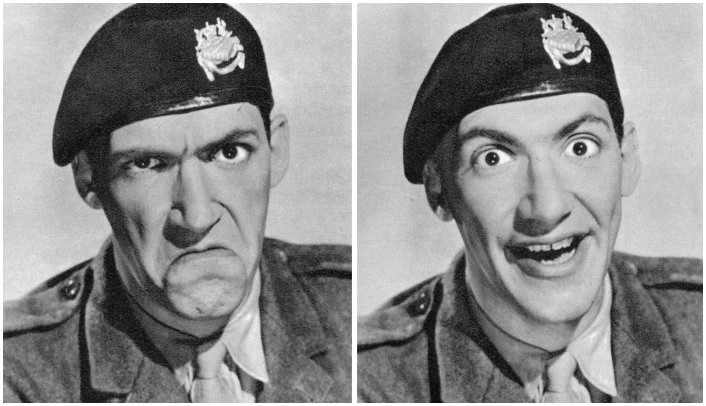

One actor stands out above all – this is Donald Wolfit’s film. The cantankerous Wolfit is perfectly cast as the larger-than-life Dr. Callistratos. He has been accused of both overacting and underacting in this movie. I don’t really think he does either. While his performance can certainly be described as hammy, I don’t think it is over the top. On the contrary, Wolfit is surprisingly restrainted throughout the movie. He does, however, play the role as the caricature that it is – and walks through the entire film with a perpetual air of sourness and tension – he always seems on the brink of bursting out into belalugosian declamations, but he never does. This, in combination of his Shakespearan dictation creates a heightened performance: at no point do you think this a man who could exist in real life; but neither does Wolfit ham it up as to make the character tip over into unintentional comedy.

The only other actor with anything you’d call name recognition in Blood of the Vampire is Barbara Shelley, who would later go on to fleshier roles as a scream queen in several Hammer horrors. While Sangster should be given credit for creating a female lead with actual agency in Blood of the Vampire, the role of the proper Madeleine doesn’t give Shelley any chance to shine. Vincent Ball is quite good in the lead as John Pierre, but it’s another one of Sangster’s bland leading man roles. William Devlin makes an impression as Pierre’s cell mate, but gets too little screen time, whereas Victor Maddern as the hunchback Carl gets too much, as Sangster and Cass like to present his hideous visage as much as possible, but fail to create any meaningful story arc for him.

Blood of the Vampire is not a particularly good film, mainly because it feels like throws everything at the wall in the hopes that something will stick. On the other hand, this abundance of plot makes for a breezy and entertaining watch, greatly helped by Donald Wolfit’s electrifying presence and a solid cast of character actors filling out the rest of the cast. If you like horror movies in the vein of Hammer, then you will probably enjoy this one as well.

Reception & Legacy

Blood of the Vampire was released with the now almost obligatory X rating in the UK in August, 1958, distributed by Eros Films. Eros had sold the US distribution rights to Universal, and it premiered oversees in October, 1958, on a double bill with Universal’s own Monster on the Campus (review).

Somewhat surprisingly, given their loathing for Hammer’s Frankenstein movies, British trade magazine Monthly Film Bulletin gave Blood of the Vampire a positive 2/3 rating, praising the art direction, the sympathetic nature of Carl (which is a debatable point) and Donald Wolfit’s performance.

The US trade press all touted the film’s box office potential, noting that the colourful blood and gore was going to go down well “in indiscriminate theatres”. Motion Picture Daily called the film “a first-class job in its genre” and Harrison’s Reports labelled it “a top shocker of its kind”.

However, some papers also noted the film’s artistic flaws. The Film Bulletin said that for all its shock and gore, it was for the most part “a pallid, mid-Victorian spook show with a loose-ends plot” and Rich in Variety commented on the “silly proceedings”. He continued: “There is not much in the direction, acting or dialogue in this picture. Jimmy Sangster, who has made a corner for himself in the British film horror stakes with his “Frankenstein” screenplays, is finding the field less fertile than awhile ago.”

As of writing, Blood of the Vampire has a middling 5.5/10 rating on IMDb and a slightly better 2.8/5 rating on Letterboxd.

Onlibe critics are somewhat divided on the movie. Kevin Lyons at The EOFFTV Review compares it unfavourably to Hammer’s movies, opining that director Cass “seems as disinterested in the material as Wolfit, dutifully plodding through the script and failing to capture the Gothic atmosphere and sheer energy that Terence Fisher had so effortlessly brought to The Curse of Frankenstein“. Glenn Erickson finds fault with almost everything in the film over at Trailers from Hell: the weak characterisations, the lack of character arcs, Sangster’s all-over-the-place script, amateurish matte painting and Henry Cass’s mundane direction, however, he adds: “I thoroughly enjoyed it”. On the other hand, Richard Scheib at Moria gives the film 3/5 stars, writing that “Henry Cass has a visual eye that rivals that of Terence Fisher“, praising the matte paintings and Sangster’s well-written character ars. Take away from these conflicting testimonies what you will.

Cast & Crew

Producers Monty Berman and Robert S. Baker met when they were both working for a film unit during WWII. Both had done some work in the British film industry as cameramen or cinematographers, Berman had greater experience, working for example as a cinematographer for Ealing Studios. The two befriended and after the war founded their own production company, Tempean Films. Together they produced around 30 low-budget movies and some TV series. The first ten years of its operation produced largely forgettable but competent quota quickies, primarily crime and mystery films. However, the company is best known for its work in the late 50s and 60s, including the TV show The Trollenberg Terror (1956), as well as the movies Blood of the Vampire (1958), The Trollenberg Terror (1958), Jack the Ripper (1959) and The Hellfire Club (1961). In 1962 Tempean Films managed to secure the TV rights to Leslie Charteris’ character Simon Templar, or The Saint, a gentleman thief and vigilante who entertained readers in several novels and short stories beginning in the 30s. The Saint ran between 1962 and 1969, turned lead actor Roger Moore into an international star, and is widely held as one of the main inspirations for the James Bond movies. Around 1965, Baker and Berman went their separate ways, with Baker continuing to make films and Berman producing TV shows, such as the sci-fi series The Champions (1968-1969) and the spy-fi series Department S (1969).

Director Henry Cass was originally a stage actor, and during most of his career also a prolific director for the stage. He started directing films in the late 30s and his directorial career spanned around three decades and some 25 feature films. He also produced and/or wrote a handful of them. All of his films were quota quickies, and he has left no great mark in British film history. Blood of the Vampire (1958) remains his best known movie.

Sir Donald Wolfit was a legendary British stage actor who at one time set the standard for playing Richard III (until Olivier came along). As renowned for his acting, as for his vanity and his temperament, he was infamous for leading his theatre troupe like a tyrant and for always surrounding himself with mediocre actors, in the fear of someone upstaging him. However, he was also praised for bringing Shakespeare out of West End and to the masses with his touring company, selling tickets to his shows for affordable prices. Wolfit did also appear infrequently at prestigious theatre houses like Old Vic and Stratford-Upon-Avon, but like his film appearances, he took these jobs only in order to finance his own stage company. He appeared in three movies that were nominated for best film Oscars: Room at the Top (1958), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Becket (1964), in which he miraculously managed to work with his arch enemy John Gielgud without killing him. His most famous role, however, is probably the title role of Svengali (1954), in which he hypnotises Hildegard Knef. He also appeared in the space exploration film Satellite in the Sky (1956, review), Blood of the Vampire (1958) and The Hands of Orlac (1960).

Vincent Ball, who plays the romantic lead in Blood of the Vampire (1958), is a name that might be recognised among Australian film and TV buffs, but not by many others. His road to the big time is perhaps more interesting than his actual career. While working as an accountant in Australia in 1949, he sent out applications to film studios around the world asking for a chance to audition. He was invited by the Rank Organisation in Britain to audition for a role in The Blue Lagoon (1949), and mustered as a stoker on UK bound cargo ship, but the trip ended taking six months rather than the expected six weeks, so when he arrived, filming was already underway. However, he got a job as an underwater double for Donald Houston on the film, as Houston couldn’t swim. Ball trained at RADA and was able to move from bit-parts to supporting roles, and the occasional lead in low-budget movies. In the 70s Ball moved back to Australia, where he became a recognised character actor in numerous TV shows and movies, perhaps best remembered for his appearance in the war film Breaker Morant (1980). His only SF appearances are Blood of the Vampire and the comedy The Mouse on the Moon (1963).

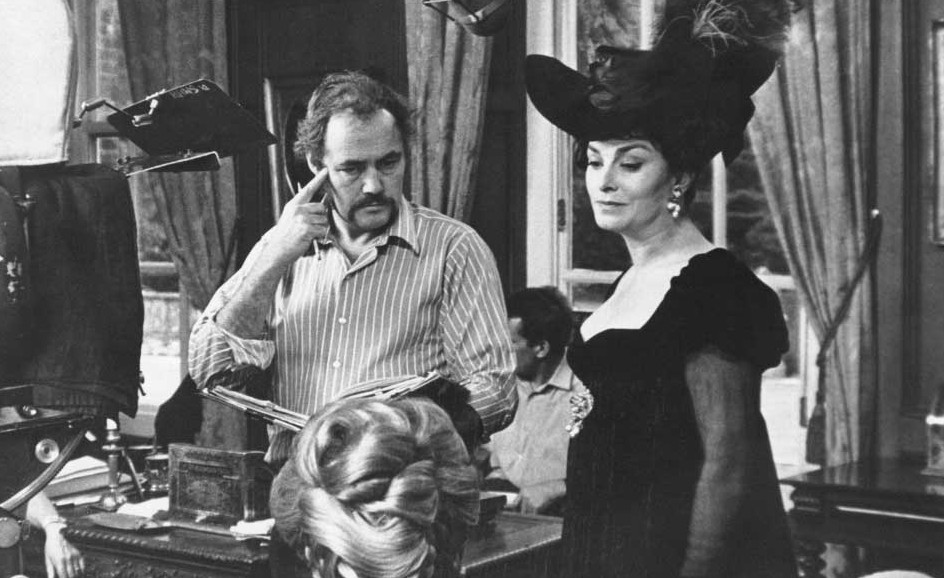

Barbara Shelley was the stage name of Barbara Kowin, born in 1932 in London. As a young woman, Shelley wanted to get into acting, and started modelling in order to cure her stage fright, which only led to minor roles in movies – Shelley realised her modelling was hurting her acting career, as she wasn’t being taken seriously. In 1953 she went on holiday to Rome, where she was “discovered” by Italian actor Walter Chiari. She remained in Rome for four years, changed her stage name and appeared in eight Italian movies, learning the language along the way. She returned to London in 1957, and was immediately cast in her first horror lead in Anglo-Amalgamated’s Cat Girl (1957), after which Hammer cast her in the war film Camp on Blood Island (1958), marking the beginning of a long and fruitful relation.

During her career, which lasted into the early 90s, Shelley appeared in over 30 films in different genres, as well as around 70 TV shows, including several televised plays. She also performed on stage, at one time even with the Royal Shakespeare Company. However, she quickly became a favourite of horror movie producers. According to an obit in The Guardian, Shelley’s strength was that she “possessed a grounded, rational quality that instantly conferred gravitas on whatever lunatic occurrences were unfolding around her”. After her death in 2021, her agent said, according to BBC: “On screen she could be quietly evil. She goes from statuesque beauty to just animalistic wildness.” Having made an impact in Cat Girl, she was cast in Tempean Films’ Hammer ripoff Blood of the Vampire (1958), followed two years later by MGM’s SF/horror movie Village of the Damned (1960), based on John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos, in which she played the mother of one of the possessed kids.

Shelley’s heyday with Hammer lasted from 1964 to 1967, when she starred in four of the studio’s most well-regarded films. In 1964 she was cast in The Gorgon, as the woman who becomes obsessed by the spirit of a Greek mythological monster, a gorgon (think: Medusa). Shelley offered to play the monster wearing live snakes on her head, but the studio wanted another, “uglier” actress to play the monster, and instead used rubber snakes. Shelley later said that it was the biggest regret of her career that she didn’t fight harder for the right of playing the monster – with real snakes, as she thought the rubber effects looked terrible. Two years later she appeared two Hammer horrors, Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966) and Rasputin: the Mad Monk (1966). Shelley’s role as one of Dracula’s brides is the one that she is particularly well remembered for – from her seductive, sensual performance as she lures victims to their death, to her explosive evilness in the scene where she is staked on an altar. Paradoxically, her most famous scream in the film was dubbed by another actress. Her last Hammer horror role was as one of the scientists trying to save the world from the aliens in Quatermass and the Pit (1967), adapted by Nigel Kneale from his own TV series. Blood of the Vampire, Village of the Damned and Quatermass and the Pit can all be considered science fiction. Shelley also appeared in a numbet of SF TV series, including The Avengers and Dr. Who.

Shelley later described Hammer as an extremely talented family, and said that she adored working with Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. She recalls they had loads of fun on together, and would constantly joke around on the sets. She never had any regrets about being typecast as a scream queen, and stated that she was taken aback later in life by how much her performances had meant for horror fans; “I realised that my work had been appreciated and that I had – through those horror films – actually reached a far bigger audience than I would ever have done if I’d stuck to the theatre”. Shelley did, however, have a bit of a beef with the way in which sex and nudity was exploited in the horror genre. When she filmed a nude scene in Cat People, she would write “STOP” on her chest, in order to prevent the camera man from panning too low. She also refused an unscripted nude scene in Blood of the Vampire. On the other hand, she said, she had no qualms about getting naked in front on the camera if the moment was scripted and served a purpose for the story: “The scenes I refused to do were when they suddenly would say to me, ‘Oh, you take your clothes off here’. The answer to that was always no.” Barbara Shelley passed away in 2021 due to complications arising from having been sick with covid-19.

The rest of the cast is largely made up of distinguished British character actors. In Blood of the Vampire (1958), Victor Maddern gets an unusual, and unusually large, role as Carl the hunchback. RADA-trained Maddern was a fixture on the West End stage, and appeared in over 80 movies and 100 TV shows – he often played military types, either straight or, memorably, comically. John Le Mesurier is best known to a British audience as one of the principle cast of the comedy series Dad’s Army (1968-1977), and was another actor who regularly turned up in films and TV shows. He had minor roles in Stranger from Venus (1954, review), played a judge in Blood of the Vampire (1958) and had featured supporting roles in The Mouse on the Moon (1963), War-Gods of the Deep (1965) and The Spaceman and King Arthur (1979), playing Sir Gawain in the latter.

The career of 6’7 (201 cm) actor Bernard Bresslaw might have looked quite different had he been cast, as was at one point considered, as the Creature in Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957). That same year, instead, he was cast as the dimwitted Private Popplewell in the hit TV series The Army Game. His character became the most popular character of the series, and led to a spinoff movie, I Only Arsked (1958), the character’s catchphrase. His other big breakthrough came in 1959, when he was cast in Carry on Nurse, the first of what would become numerous Carry on comedies in which he appeared during the 60s and 70s. These films provided Bresslaw with his bread and butter, while he was at the same time trying to remind film and theatre producers that he was actually a RADA-trained Shakespearan actor, despite his typecasting as the big, funny idiot. He eventually succeeded, by turning down lucrative comedy parts and settling for more serious roles in less prestigious productions, before eventually working his way up to the Royal Shakespeare Company. Bresslaw was thriving in his stage career, when, sadly, he passed away in 1993 at the age of 59.

Aside from his Carry on films and his stage career, Bresslaw also appeared in numerous other films and TV shows, both comedic and serious. In 1959 he played the lead in Hammer’s comedic take on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Ugly Duckling. While his height would have made him suitable for roles in horror movies, he very seldom played ghouls and evil henchmen, and when he did, they were mostly in comedy films. He did appear in a handful of science fiction movies; apart from the above mentioned, he also appeared as a henchman in the space western Moon Zero Two (1969) and – memorably – as the heroic cyclops in the sfifi/fantasy film Krull (1983).

William Devlin, who plays John Pierre’s cellmate in Blood of the Vampire (1958), was one of the most renowned Shakespearean players on stage. Andrew Faulds is best known for switching acting for politics, and serving as a longtime MP for the British Labour party. John Stuart was another Hammer staple, and appeared in a are 1948 TV version of Karel Capek’s R.U.R., as well as in Four-Sided Triangle (1953, review), Raiders of the River (1956), Quatermass 2 (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958, review), Blood of the Vampire (1958), Village of the Damned (1960) and Superman (1978).

In a small role as the executioner who stakes Dr. Callistratos in Blood of the Vampire (1958) we also see the great Milton Reid, show wrestler turned actor, best known perhaps for appearing as a henchman in three James Bond films; Dr. No (1962) Casino Royale (1966) and The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). Born to Scottish and Indian parents in India, Reid worked as a show wrestler in Britain before getting into films in 1958 – Blood of the Vampire was one of his very first roles. However, he made an impact in Ferry to Hong Kong (1959, opposite Curd Jürgens and Orson Welles) and Swiss Family Robinson (1960). In both movies he played a bald pirate, which cemented his image, and he shaved his head for the rest of his career.

Reid became a staple in B-movies as thugs, henchmen and exotic warriors and temple guards, appering in British, Hollywood and spaghetti movies up until 1982. He also, on several occasions, played a lamp genie both in movies and TV shows, as well as on stage. However, by the 80s, he had quit wrestling and the roles he got were small and badly paid. He then decided to move back to India and try his luck in Bollywood. He appeared in three Bollywood movies between 1983 and 1986 before he got in trouble with the law, apparently for an assault during a neighbour dispute. Apparently, he died in 1987, but his family has received no confirmation of this from Indian authorities, and his fate has remained a mystery. Milton Reid appeared in the science fiction movies Blood of the Vampire (1958) and The People That Time Forgot (1977).

Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster almost single-handedly created the Hammer horror house, one might almost say. Having worked with Hammer in different capacities, from clapper boy to production manager, from 1949 onward, he was asked by studio head Anthony Hinds to put together a script for Hammer’s X the Unknown (1957, review), originally intended as a film in the Quatermass series. The film was successful, and sangster was then tasked with writing the studio’s Frankenstein reboot The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review). Not particularly a fan of horror, Sangster was more interested in the character of Victor Frankenstein than in the creature, and wrote a script that explored the ruthless, driven, and in a sense, naive, characteristics of the mad doctor, played to perfection by a then largely unknown Peter Cushing. With strong direction from Terence Fisher, film relished in its X rating, filling it with garish blood and sawed-off body parts in luscious colour.

The Curse of Frankentein turned Peter Cushing into an international star, and Sangster’s next movie, Dracula (1958), did the same for Cushing’s co-star Christopher Lee. This double punch made Hammer the most exciting horror studio in the world, and shaped the career of Sangster, who went on to write several sequels to these movies, as well as a reboot of The Mummy (1959), and other horror movies, both for Hammer and for competitors, most notably three films for Tempean Films, including Blood of the Vampire (1958) and The Trollenberg Terror (1958).

Sangster had a knack for inserting interesting themes and character studies into his movies, often making his central characters driven outsiders, intelligent loners hampered in their work and quests by the conformism, pettiness, fear and stupidity of the people around them. But likewise, the aloofness och single-mindedness of these characters often proved their downfall. Sangster’s biggest weakness, however, was that he often struggled to fill the space between start and finish with a coherent, dramatically stringent story and defined character arcs. His films would often tread water in the middle, sending its characters on outings that had little consequence for the overall plot, just in order toll pad out the running time of the movies.

Sangster unenthusiastically continued writing horror scripts for Hammer into the 70s, but at one point set as a condition that he would also get to direct. He directed The Horror of Dracula (1970), Lust for a Vampire (1971) and Fear in the Night (1972), which were all commercial failures and received little acclaim from critics. With much more enthusiasm he also turned out a number of crime and mystery stories, that were more aligned with his personal interests. Among the better known ones are Taste of Fear (1961), starring Susan Strasberg and Christopher Lee, Paranoiac (1963) with Oliver Reed and Janette Scott and The Nanny (1965) with Bette Davis. In the early 70s, Sangster relocated to Hollywood, where he mostly wrote for TV, both horror and other genres, with reasonable success. In the 80s hes work becames scarcer and he retired in 1992. Sangster passed away in 2011.

Janne Wass

Blood of the Vampire. 1958, UK. Directed by Henry Cass. Written by Jimmy Sangster. Starring: Donald Wolfit, Vincent Ball, Barbara Shelley, Victor Maddern, William Devlin, Andrew Faulds, John Le Mesurier, Bryan Coleman, Bernard Bresslaw, Milton Reid. Music: Stanley Black. Cinematography: Monty Berman. Editing: Douglas Myers. Art direction: John Elphick. Makeup: Jimmy Evans. Produced by Robert Baker & Monty Berman for Tempean Films.

Leave a comment