As an extraterrestrial missile threatens to destroy New York, scientists and the military scramble to stop it, while civil society prepares for a disaster. This 1958 sci-fi thriller’s potential to rise above the cut is undermined by its profuse use of stock footage. 4/10

The Lost Missile. 1958, USA. Directed by Lester Wm Berke. Written by John McPartland, Jerome Bixby, et.al. Starring: Robert Loggia, Ellen Parker, Phillip Pine. Produced by William Berke & Lee Gordon. IMDb: 5.1/10. Letterboxd: 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A

An extraterrestrial missile is heading toward Earth. The Soviet air defence tries to blow it up, but only manages to divert it into an extremely low orbit around Earth, leaving a five-mile-wide wake of destruction as its intense heat incinerates everything in its path. After plowing through the Arctic, it’s now headed for Ottawa and ultimately New York.

That’s the build-up to The Lost Missile, a 1958 low-budget movie directed by Lester Wm Berke, and starring Robert Loggia in an early role. It is known for its profuse use of military stock footage, but nonetheless has a reputation as rather taut little SF propaganda thriller.

In the US, we follow the scientists working at a research facility on the outskirts of New York. Lead scientist David Loring (Loggia) is just about to complete work on his new, revolutioinary hydrogen bomb, but is pestered by his colleague and fiancée Joan Wood (Ellen Parker), who will not let him postpone their marriage again. They’re not the only couple struggling to combine work and family life. Joe Freed (Phillip Pine) has just as much as much a sense of duty to his work as David, but is torn, as he feels he should be with his wife Ella (Marilee Earle), who is about to give birth to their first child.

Meanwhile, the Canadian air force tries to blow up the mysterious missile with even less luck that the Russians. Nothing seems to be able to stop the monstrous missile, as all projectiles simply burn up in its heat before they can do any damage. Ottawa is obliterated. Serious men with serious machines hold serious conversations over radio and telephone, more fighters are sent up to try to destroy the menace, but nothing sticks. New York prepares for the onslaught and civil defence measures are taken, just as all New Yorkers have practiced. Children are evacuated from the schools to the countryside, and the adults huddle up in underground shelters.

Meanwhile, David gets an idea: using a small warhead, he believes he will be able to use his new missile, christened Joe, for some reason, to blow up the extraterrestrial killing machine, since the plutonium will withstand the heat. But he must take a small convoy of cars with the plutionium out to the launch site, which is no easy task in a city gripped by panic. His and Joan’s car gets stolen by rioting teenagers, and further down the road, the plutonium transport is forced off the road. However, the two get a ride to the lauch site. With seconds to spare, David must transport the plutonium and install it into the missile, without a protective suit. Will he make it in time, and will he survive?

Background & Analysis

The Lost Missile (1958) was initially produced by veteran low-budget producer/director William Berke, whose jungle/SF movie The Jungle (1952, review), I have just reviewed. Some sources claim he was also set to direct, with his son Lester Wm Berke as assistant director, others, including the mostly reliable Bill Warren, say that Lester was chosen as director from the start. However, I doubt that Berke Jr would have been the first choice as director, as he had only assistant directorial duties in his credit sheet at the time, and would never direct another film in his career. Whatever the case, producer William Berke died during production – some claim on the very first day of shooting, and Lee Gordon was brought in as producer, and Lester Wm Berke was – presumably – promoted from assistant director to director. The film was produced for Berke’s own William Berke Productions and distributed by United Artists.

Bill Warren writes in his book Keep Watching the Skies! that early mentions of the film in the trade press claimed the script would be written by SF specialist and author Jerome Bixby, based on a novel with the same name by pulp novelist and screenwriter John McPartland. However, no such novel exists, and it is not mentioned in the finished screen credits. In the credits Bixby and McPartland are credited with screenwriting, while director Lester Wm Berke gets story credit. But in an interview relayed by Warren, Jerome Bixby doesn’t mention any story treatment by Berke. According to Bixby, he and McPartland came up with a rough plot and then divided the scenes among themselves according to each writer’s strengths – which means McPartland wrote most of the drama and Bixby wrote everything involving science and technology. The reason producer Berke teased the film as a book adaptation was probably that in 1957 Twentieth Century-Fox had released a moderately successful film called No Down Payment based on a book by McPartland (in reality the film’s producer had commissioned McPartland to write the book so that it could be adapted into a screenplay). Actually, the practice of hawking a film as “based on a novel by” was not uncommon in Hollywood. I don’t know if there were financial reasons for this – did a writer get paid more or less for a story credit or an “based on novel by” credit? If anyone has any information on this, please leave a comment below! But my guess is also that a “based on a novel” credit was thought to lend the film a little bit of credibility and weight, especially if its premise was somewhat silly, as was often the case with low-budget SF movies. McPartland and William Berke had previously worked together on Street of Sinners (1957) for United Artists, which is probably how the collaboration between producer Berke and the writers came about.

There is no information on where the studio-bound portions of the film were shot. Berke made most of his films in New York, but since he died in Los Angeles while making the film – and did not use his usual New York DP, but a Hollywood hire – the film was probably shot in Los Angeles. UA did not own a studio facility, so Berke probably rented a small studio in Hollywood for a couple for days for interior shooting. The studio-bound footage largely consists of nondescript offices and corridors, a jeweller’s shop and other fairly mundane interior sets. Berke might also have taken advantage of some standing backlot city set. The shots of the Soviet brass are filmed in a dark space next to a staircase, and was probably shot either on a standing set or in an actual house somewhere.

The movie is perhaps best known for its profuse use of stock footage. A pre-credit text thanks the US department of defense and the US military for their help with the movie, claiming the movie could not have been made without it. This is a not very successful way in trying to obfuscate that much of the film’s running time is made up of stock footage from military information and propaganda reels. There’s also a good amount of stock footage from New York, Canada and a few other locations. AFI claims that there was new footage shot on location in New York, but I have found no actual confirmation of this. However, since Berke was primarily a New York operative, it is possible that he shot some New York footage while there. The credits do, however, list a Canadian unit managed by Roy Krost. A member of the Classic Horror Film Board claims as certain knowledge that “Real Benoit Film Productions, Montreal, shot the Canadian location scenes on an Arriflex camera”.

As for the story itself, regular readers of this site will notice that the plot description above is one of the shortest I have ever written. The plot is simple and straightforward, without any large detours or subplots. Little time is spent on setup or explanations, and the movie opens almost in medias res. The missile in question is never explained: we know it comes from outer space, but that’s all we know during the entire film. With a different script, this could have been a detriment, but here it works to the film’s benefit. This is not about the missile or about the beings that sent it toward Earth, but about the people and the societies that deal with the situation. It is really more of a disaster movie than a science fiction movie.

There are also a couple of interesting perspectives on the topic. Both David and Joe are challenged by their wives (or would-be wives) about their propensity to put their work ahead of their family life. In and of itself this is nothing new – half of these type of films have wives complaining their husbands neglect their families for their work. What makes this film a bit different as that the women in this film seem reasonable in their criticism, and one is tempted to side with them. Plus, one of the male characters, Joe, has serious qualms about his negligence of his wife. Ultimately the film does side with the men and their duties, however, which undermines the film’s efforts to show a “feminine point of view”. One of the main themes of the movie seems to be an exploration of the duty of every man to place his life in the service of the nation. In the end, David is willing to sacrifice his life in order to save New York from the missile, leaving his distraught fiancée crying by the wayside.

It’s also interesting to see how much emphasis is put on the civil emergency response. A long stretch of the movie depicts how New York prepares for the imminent disaster, with the evacuation of school kids and people taking refuge is shelters. It also doesn’t shy away from the darker sides of social interaction in the face of impending doom, such as people fighting over a place on the last train to leave New York, or delinquents hijacking David’s car when he drives the warhead out to the missile launch site. Be it that this last bit tests the limits of credibility: the whole thing almost becomes a scene from Mad Max. There’s also a couple of moments of unintentional comedy in the mix, where the movie takes itself a little too seriously and inserts a little too much pathos in rather inapproriate settings.

All in all, The Lost Missile has all the trappings of a fairly taut little low-budget disaster thriller, spiced with some ideas that are perhaps not original, but have at least been given an intresting spin.

For the most part, the movie is backed up by good or decent acting. In particular, the two leads, Robert Loggia and Phillip Pine, give very good performances. Ellen Parker, in her last role, as David’s fiancée Joan, does not come off to her benefit, as she doesn’t seem sure if she’s supposed to underact or overact, and resorts to doing both at any given moment. This feels like something that can be chalked up to the misfortune of having an unexperienced director forced on the movie by the circumstances.

Lester Wm Berke directs the film in an almost documentary style, and seems to have instructed the actors to perform accordingly. Hence the performances are generally restrained, minimal, and underacted. This works well in many instances, but in others gives the impressions that the actors are simply reading their lines without any motivations behind them. Offsetting the documentary feel is Phillip Pine, who has been given the task to appear as the wiry, emotional type of the movie. For the most part, Pine gives an excellent performance, bringing some much needed colour and emotion to the movie. An exception is the scene in which he suddenly has a change of heart about destroying the missile and goes on a lunatic rave about the importance of studing the missile from outer space – FOR SCIENCE! This is another tired trope from a number of SF movies: a reasonable scientist or astronaut suddenly breaks down in a fit of madness which threatens the future of mankind. Oftentimes, these were religious breakdowns, but “scientific breakdowns” were not unheard of either. It’s a silly trope and consequently Pine comes off as silly in the scene.

The Lost Missile fits snugly under the umbrella of cold war message films. While the Russians are not the primary menace here, the titular missile carries all the fears and anxieties of the US public about a Russian nuclear attack. The movie highlights the important work that scientists, the military and the civil defence do in order to keep Americans safe, while it also stressing the duty of every single man to put his shoulder to the wheel in order to defeat communism – even if it meant sacrificing your family life or even your own life. This is standard fare, but the propaganda is subtle and symbolic enough that it doesn’t feel like you’re being bludgeoned in the head with it.

The mass of stock footage provides much of the movie’s needs in terms of special effects – we have fighter jets zipping across the skies, explosions, natural disasters, crumbling buildings, etc. However, special effects man Jack Glass also provides a bit of new effects, such as footage of the missile itself, constantly cleaving the atmosphere. Footage of the thing closing in on Earth betrays the film’s low budget, as does the fact that we never actually see it flying over terrain. Instead we have several shots of it flying while the background is obfuscated by its glow and “speed blur”. The destruction it causes is handled by gradually overexposing landscape and cityscape shots, then cutting to the distruction, either in the way of stock footage or painted landscapes. Most of the paintings are not even matte paintings, but simply shots of paintings, probablt done by Glass himself – as he was an accomplished matte painter. The effects are not terrible by the standard of low-budget movies of the time, but they do reveal the film’s budget and schedule limitations.

Apart from Two Lost Worlds (1951, review), The Lost Missile must be the film I have reviewed with the most amount of stock footage. I don’t think I am exaggerating if I claim that close to 50 percent of the film is stock. To be fair, the repurposed shots are well integrated into the story, and editor Everett Sutherland is worthy of praise for his work. And it’s not just military footage, even if those dominate the movie, but also cityscapes, laboratory, computer and science footage, disaster footage, etc.

In order to make it all fit, the film makes use of a great deal of voice-over narration by Lawrence Dobkin. I know narration in movies was a thing in the 50s, thanks to TV documentary-style crime series like Dragnet, but nevertheless it usually comes off as somewhat irritating to to me, unless it has a clear artistic purpose. When narration is used simply to tell the audience things it needs to know to understand the story and move the plot along, it always strikes me as bad writing – radio for TV. The Lost Missile doesn’t have the worst narration I’ve experienced, but like the stock footage, there’s simply too much of it.

Modern critics are all quick to point out that the profuse use of stock footage is to the film’s detriment, but just as quick to forgive this flaw, stating that the film holds together nonetheless. I disagree. The Lost Missile has just enough originality – that is to say slight and sometimes surprising variations of familiar tropes – to give it a chance to rise above the cut in the deluge of low-budget SF movies produced in the late 50s. However, there’s just so many minutes I can stand watching stock footage of fighter jets, rocket launchers, spinning radar dishes, jet plane dashboards, army jeeps, old-timey computers, men speaking on radios, men pushing buttons and men taking notes before I get extremely bored. If you’re a fan of military hardware – I know there’s SF fans out there who can name every single vehicle seen in the movie (and point out that they are inappropriate for the film) – then this might me right up your alley. However, I have zero interest in such matters and feel that every vehicle in a movie should serve a plot purpose and not simply be inserted as padding and/or illustration. We don’t need 20 minutes of jet and rocket porn in order to establish that conventional weapons are useless against the missile. All the stock footage undermines what could have been a nifty little SF/disaster thriller and turns it into a yawner.

Reception & Legacy

The Lost Missile was released in December, 1958, and considering what must have been a very low budget, it probably made its budget back at the box office.

The film received generally positive reviews in the trade press. The Motion Picture Daily – which generally gave everything a good review – praised the movie’s “stark reality” and suggested it will “make its point with frightening impact”. Powe in Variety said it was “strong in its use of stock footage and special effects, less so in its portrayal of human elements”. The paper continued to say that the stock footage “provide the greatest interest and reality”, however the “actors are less happily served by the screenplay which is not always too clear on sequence and goes overboard heavily on melodrama”. Jack Moffitt at the Hollywood Reporter called it “exciting” and “a good suspense story”, also praising the way dramatic and stock footage were edited together, “as to constitute a minor masterpiece in documentation”.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies (1984), Phil Hardy calls The Lost Missile a “slackly scripted and weakly directed offering”. Bill Warren, on the other hand, writes in Keep Watching the Skies! (2009): “This cut-rate disaster film is efficient, making good use of little-seen stock footage and utilizing its low budget to the fullest. Let down by mediocre special effects – the idea is too ambitious for its budget – the story also tends to be repetitious, but for a short, unpretentious film, it’s not bad.”

As stated earlier, modern critics mostly seem to have a soft spot for The Lost Missile. Jeff Stafford at Cinema Sojourns calls it a “highly entertaining and, at times surprisingly effective, end-of-the-world thriller in spite of the minimalistic, almost abstract quality of the special effects”. Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV says: “underneath the obvious poverty of it all and the very wobbly science, there’s an intriguing story at work here that elevates it a rung or two above the average”.

Not everyone are sold, though. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings, like me, is put off by the over-use of stock footage: “there’s […] far too much of it for the movie to handle, and after a while my patience wears out. It’s a shame; this would have made an above-average thriller if a little more money had been thrown into it.” Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum writes: “the crummy execution is unforgivable. Despite the promising set-up, The Lost Missile drowns in an ocean of excessive narration and an overabundance of stock footage.”

Cast & Crew

Producer William Berke died during the production of The Lost Missile. He started his career as a writer of silent westerns in the ealry 1920s, and in the early sound era advanced to producer and director. He directed nearly 100 films between 1934 and 1958, almost exclusively B-movies with 10–12 day shooting schedules and budgets of around $100,000. During the 30s and 40s he was employed by the B-movie units at Columbia, RKO and Paramount, before ending the bulk of his movie career with Robert Lippert in the early 50s. At first, Berke almost exclusively made low-budget westerns, many of them starring Charles Starrett and Russell Hayden as the dynamic duo Steve & Lucky, but he also directed numerous films with westerns star Don “Red” Barry. At RKO he got the chance to produce and direct other genres, and proved particularly proficient with crime dramas, navy films and jungle movies, but was also a capable hand with musical comedies.

William Berke was often teamed up with actors Richard Arlen, Robert Lowery, Jon Hall and Hugh Beaumont – all familiar from science fiction movies we have reviewed on Scifist. He made seven of Columbia’s 16 Jungle Jim movies starring Johnny Weissmuller between 1948 and 1953, and also directed and handful of films starring Tom Conway as the vigilante the Falcon. Between 1953 and 1956 Berke mainly worked in TV, but returned to feature films in 1957, at United Artists. Berke directed only two science fiction movies, The Jungle (1952), filmed on location in India, and The Lost Missile (1958), which turned out to be his last movie, as he died of a heart attack on set, aged only 54. His son, Lester Wm. Berke, who worked as an assistant director, finished the movie. Actress Marie Windsor, who worked with Berke in India during the making of The Jungle (1952, review) describes him as “such a wonderful little guy” who “worked so hard under terrible circumstances”.

The Lost Missile was Lester Wm Berke’s only directorial effort. Son of William Berke, he startd working as an assistant director in the mid-50s, both in film and TV. In the 70s he also started to get into the production side of TV, working as both producer and production manager on over 50 TV movies or series. For example, he was the main producer for Quincy, M.E. for four years.

Screenwriter Jerome Bixby, born 1923, was a writer of short stories as well as screen and teleplays. Today he is probably known mostly for writing the script for It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review), which has been cited as a great influence on Alien (1979).Although he is best remembered for his work in the field of science fiction, only 300(!) of his 1200(!) short stories are SF. During the early 50s, he briefly worked as an editor for a handful of magazines, including Planet Stories, Jungle Stories and Action Stories. Bixby was an extremely prolific writer of primarily western, SF, fantasy and horror stories. His perhaps best remembered and regarded story is It’s A Good Life (1953) about a small boy with godlike powers, who keeps his small community in terror. It was adapted for one of the most well-regarded episodes of The Twilight Zone in 1961. Bixby also wrote five episodes for the original Star Trek series in the 60s, including “Mirror, Mirror”, in which a transporter malfunction swaps Captain Kirk and his command crew with their evil counterparts from another dimension. It is generally regarded as one of the best shows in the series.

Bixby wrote the screenplays for It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958) and Curse of the Faceless Man (1958), The Lost Missile (1958) and contributed to the story of Fantastic Voyage (1966). The last work based on his material was The Man from Earth (2007, another version made in 2017), the script of which he finished on his deathbed in 1998, and is a fixup script based on several of his stories. The SF Encyclopedia writes; “Bixby’s work is professional and imaginative, but he clearly wrote too hurriedly and all too often excellent ideas fail to generate memorable stories”.

Second screenwriter John McPartland was a prolific pulp novelist and occasional screenwriter, who is only of marginal SF interest. Almost all of his novels were hard-boiled detective stories, apart from his more standard novel, No Down Payment. However, that book was a commission from screenwriter Phillip Yordan, who turned it into a film with the same name. The Lost Missile was the only time McPartland dabbled in science fiction.

If the name Robert Loggia doesn’t immediately ring a bell, then at least you’ll recognise his face – 80s kids will know him as the guy who danced on the walking piano with Tom Hanks in Big (1980), or as the mobster Frank Lopez in Scarface (1983). Loggia had few leads in his career, but over the years he became one of the most recogniseable supporting actors in Hollywood. Success didn’t come quickly, though, and for decades Loggia was stuck in minor roles, often playing anonymous heavies. However, things changed when he was cast as Richard Gere’s bum dad in the boot camp drama An Officer and a Gentlemen (1982). The next year he played his perhaps most famous role as the mobster Frank Lopez who sets up Al Pacino in the classic Scarface (1983). The courtroom/murder thriller Jagged Edge (1985) saw him in a supporting as a private detective. Much to Loggia’s surprise, the role earned him an Oscar nomination.

Loggia’s career was at its peak in the 80s, when he would have several prominent and memorable roles in a numner of hit movies. He was another mobster opposite Jack Nicholson and Kathleen Turner in Prizzi’s Honor (1985), Sylvester Stallone’s father-in-law in the arm wrestling Rocky ripoff Over the Top (1987) and memorably as Tom Hanks‘ mentor and ally at the toy company in Big (1988). The role earned him a Saturn award for best supporting actor. While his star faded a bit in the 90s, he was still very much in demand for a variety of roles both i smaller and mid-budget movies. He had a rare turn in a blockbuster in the fairly prominent role of Commander Grey in Independence Day (1996) and then appeared in a minor part in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997). Loggia seems to have been an actor of the caliber that likes to work, no matter what the work is, and he kept busy even after turning 70 in the year 2000. However, approaching his octogenarian milestone, decent roles started to run dry, and he was to an increasing degree confined to super-low-budget films that would use his marquee value to gain recognition for their movies. In the process, Loggia found himself spearheading a number of somewhat questionable films – special mention must go to the legendarily terrible anti-abortion movies The Life Zone (2011) and Cries of the Unborn (2017). Just before his death in 2015, he made a cameo in the generally panned Independence Day: Resurgence (2016), reprising his role as General Grey.

Apart from The Lost Missile (1958) and the two Independence Day movies, Loggia doesn’t have a ton of SF credits from the big screen – the only one is Bille August’s Swedish-Danish-German co-production Smilla’s Sense of Snow (1997). He did appear in the 1987 spoof Amazon Women on the Moon, but his character was cut from the theatrical version, and only appears in the TV and DVD cut. He played the main villain in the mini series Wild Palms, about a corporate takeover of the US using virtual reality as a means of control, and appeared as a guest star on over half a dosen SF TV shows.

The rest of the cast is fairly anonymous. Female lead Ellen Parker only appeared in 10 movies and is not to be confused with the later Ellen Parker, known for her work on the soap opera Guiding Light. Phillip Pine, who plays Joe, had a long career playing mostly bit parts and TV guest spots. The same pattern continues among most of the rest of the cast, which consist mainly of people with only a handful of movie credits or bit-part character actors – as well as a good deal of amateurs. Fred Engelberg, who plays a memorably daft (unintentionally) TV musician who gets interrupted with a public announcement about the missile, also had a substantial role in Dinosaurus! (1960).

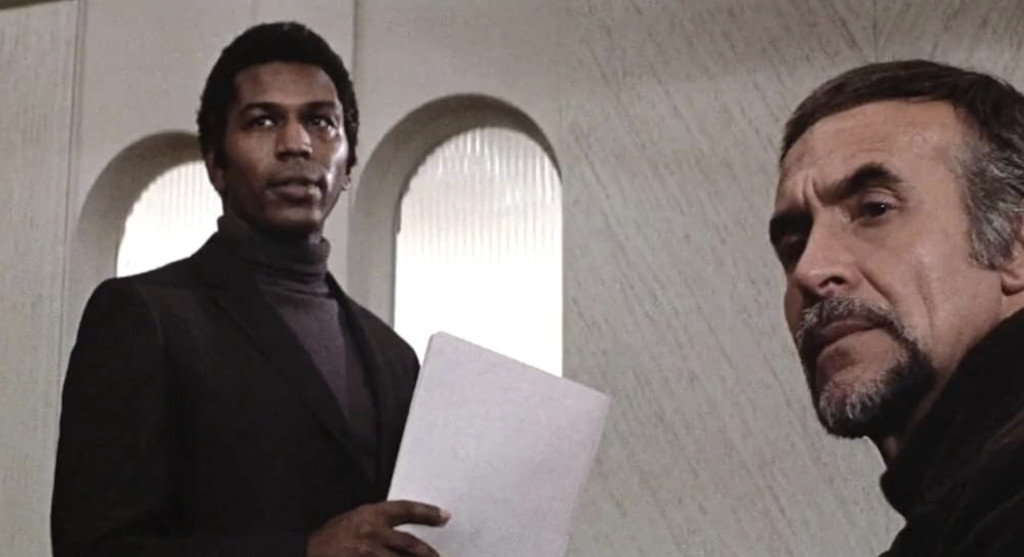

There are a few exceptions. African American Hari Rhodes became a sought-after character actor in the 60s and 70s. He may be best known for his prominent role as Mike Makula on the hugely popular animal-themed show Daktari (1966–1969), in which he appeared in nigh every episode – or indeed as He also co-starred opposite Leslie Nielsen in the short-lived crime series The Bold Ones: The Protectors (1969–1970). He set a TV milestone in the science fiction show The Outer Limits in the 1964 episode “Moonstone”, in which he played a black member of a lunar expedition, two years before Nichelle Nichols took her place at the bridge in Star Trek as Lt. Uhura. With his authorative air and commanding voice, Rhodes spent much of his career playing police officers or military types.

On the big screen Rhodes had a rare lead in the sociopolitically conscious blaxploitation movie Detroit 9000 (1973) – as a cop. He had a major role as a patient at a mental institution in Samuel Fuller’s acclaimed Shock Corridor (1963), playing a black student who believes he is a white member of the Ku Klux Klan. He played a doctor in Michael Crichton’s medical thriller Coma (1978), starring Geneviève Bujold and Michael Douglas. Fans of science fiction will recognise him as the aid to the villain in Conquest of the Planet of the Apes who grows into an ally of Roddy McDowell’s Ceasar. His first science fiction outing was in a bit-part as a pianist in The Lost Missile (1958). He followed it up with a slightly bigger role in John Sturges‘ viral thriller The Satan Bug (1965). The afore-mentioned trio remained his only theatrical SF movies, but he did have a co-lead in the bland 2001-inspired TV movie Earth II (1971), which was actually a failed pilot for a TV show. He also turned up in over a dozen SF TV shows as a guest star. Rhodes likewise starred in a handful of other TV movies. He kept busy acting until his death in 1992.

Character actress Viola Harris had few large roles in her 60-year career, but is remembered for appearing in small parts in a number of Woody Allen films. In an uncredited blink-and-you’ll-miss-it part as as an air force general we see Robert Shayne. While never a leading man per se, Shayne had nonetheless been a respected supporting actor throughout the 40s and early 50s, even playing the lead as the mad scientist/monster in SF/horror film The Neanderthal Man (review) in 1953. A capable actor with numerous turns in science fiction B-movies, it’s a shame that Shayne was relegated to a glorified extra in the late 50s.

Composer Gerald Fried was nominated for an Oscar, six Emmys and won one Emmy, for his work with Quincy Jones Roots (1977). An oboist and composer, he moved to Hollywood in the early 50’s, invited by Stanley Kubrick. Fried scored Kubrick’s first five films, including his breakthrough, Paths of Glory (1957). Apart from his work with Kubrick and on Roots, Fried is probably best known for composing music for Star Trek, in particular the percussion and brass heavy “The Ritual/Ancient Battle/2nd Kroykah”, for the scene in the episode “Amok Time” (1967) in which Spock and Kirk engage in a deadly duel. The piece, often dubbed “Star Trek Fight Music”, has been reused in several episodes and TV films. Fried kept composing almost up until his death in February 2023.

Janne Wass

The Lost Missile. 1958, USA. Directed by Lester Wm Berke. Written by Lester Wm Berke, William Berke, John McPartland, Jerome Bixby. Starring: Robert Loggia, Ellen Parker, Phillip Pine, Larry Kerr, Marilee Earle, Fred Engelberg, Kitty Kelly, Selmer Jackson, Hari Rhodes, Viola Harris, Lawrence Dobkin, Robert Shayne. Music: Gerald Fried. Cinematography: Kenneth Peach. Editing: Everett Sutherland. Set designer: William Ferrari. Sound: Jack Solomon. Special effects: Jack Glass. Makeup: Allan Snyder. Produced by William Berke & Lee Gordon for William Berke Productions & United Artists.

Leave a comment