In a near future, Soviet scientists are trying to figure out how to send a manned mission around the sun, but are thwarted by deadly “dead zones” in space. Made by documentarians, this minor 1959 effort uneasily straddles the gap between edutainment and SF drama. Visually neat, but lifeless. 3/10

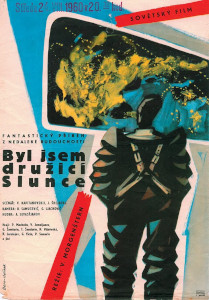

Ya byl sputnikom solntsa. 1959, USSR. Directed by Viktor Morgenstern. Written by Vladidmir Kapitanovsky, Vladimir Shreiberg. Starring: Pavel Makhotin, Vladimir Emelyanov, Georgiy Shamshurin, Anatoliy Shamshurin. IMDb: 5.8/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

In an unspecified near-future year in the Soviet Union, Young Andrey (Anatoliy Shamshurin) finds a bunch of old clippings from the early space missions in his father’s accidentally unlocked safe. He also find an old toy – and video tapes recorded at his father’s workplace, the Soviet space agency. One of them shows a recording from the cockpit of a rocket, piloted by Igor Kalinin (Vladimir Emelyanov) — and he is out in orbit around the sun, searching for something. At this point Andrey’s father Sergey(Georgiy Shamsurin) returns home and catches him in the act. Instead of reprimanding the boy for digging in the forbidden safe, Sergey asks if Andrey has seen any other tapes. When Andrey says he hasn’t, his father smiles and says that the cosmonaut on tape, Kalinin, was one of the greatest scientists who ever lived, and that the toy in the safe was a present for his son’s first birthday – “I will tell you more about it someday”, say Sergey.

That’s the start of the 1959 Soviet science fiction movie I Was a Sputnik of the Sun, or Ya byl sputnikom solntsa, or in the original Cyrillic: Я был спутником солнца, sometimes also titled I Was a Satellite of the Sun, or simply Satellite. Intended as both an edutainment film and a propaganda vehicle for the Soviet space program, it was produced by Mosnauchfilm and directed by documentary filmmaker Viktor Morgenstern.

We come back to Andrey as an adult, played by Pavel Makhotin, still narrating his own life in a voice-over, as he did in the prologue. Andrey is now himself one of the foremost scientists in the Soviet space program, overseeing a mission to retrieve an automatic laboratory that has been lost somewhere in the orbit of the sun. His team oversees a test flight with a monkey that comes back with radiation poisoning and dies. Now, there’s a lot of science talk here, and I’m not sure I could make heads or tails out of it, but there’s two problems going on. One is the the fact that the ground teams lose radio contact with the rockets and satellites going up around the sun. After much to and fro, they come to the conclusion that the reason must be Kalinin’s discredited theory of so-called “dead zones” in space, described by the narrator thus: “Between the worlds lie regions where no light travels — the so-called dead zones. There, particles cease their motion, and all instruments fall silent.” The other problem is that they don’t understand why the monkey got radiation sickness, since their measurments of radiation outside the rocket at the time that the rocket picks up radiation is within normal parameters. Again, after much to and fro, they realise that the radiation is built up by the nuclear rockets the space ship uses to blast through a meteor shower.

So, with all this worked out, the team decides that they need to send a manned rocket to retrieve the missing space lab in orbit around the sun. This is when it is revealed that Andrey is in fact the son of the great Kalinin, whom Sergey has adopted after Kalinin died on his mission. Out of a sense of duty to his father, but more importantly, to mankind and communism, Andrey volunteers to be the pilot on the dangerous flight. Said and done, he flies out to the sun, and predictably loses contact with Earth in one of the dead zones, and encounters a meteor shower, which he only barely shoots his way through. Unfortunately, in doing so he uses up almost all his ship’s nuclear power. When he reaches the space lab, is faced with a choice: leave the lab where it is and use the last of his power to get back to Earth, or transfer the power to the lab and send it to Earth with all its valuable information about the dead zone, thus helping to advance Soviet science and mankind’s further explorations of space. Naturally he chooses the latter, thus sealing his fate, becoming forever “a Sputnik orbiting the sun”. But luck is on his side, and he eventually emerges from the dead zone and is able to contact Earth, and somehow make it back home.

Background & Analysis

I have found very little information on the production of this 1959 film, which seems to have been rather rare for a long time, since it has very few mentions or reviews online.

I Was a Sputnik of the Sun was produced at the tail end of the 50s, when science fiction was returning to Soviet cinemas. Cosmic Voyage (1936, review) was the last full-on SF movie produced under Stalin’s rule. The genre wasn’t considered kosher under the guidelines of Soviet realism. However, during Nikita Khrushchev’s de-Stalininsation program, the constraints on art and entertainment were loosened. Furthermore, after the launch of Sputnik in 1957 and the US-Soviet space race in full swing, Soviet leaders were happy to use the arts to drum up support and enthusiasm for their costly space program. In 1957 a very impressive speculative film, space movie pioneer Pavel Klushantsev’s Road to the Stars, was made. 48 minutes long, it is an documentary/edutainment film with a fictionalised biography of Russian rocket/space pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and the current state of affair in space science in 1957, as well as a look at the future of space exploration. A couple of other SF movies, more in the entertainment line, were made in 1957 and 1958, but 1959 really marked the comeback of the Soviet space film with I Was a Sputnik of the Sun and Nebo sovyot (“The Heavens Call”), probably best known as the film that Roger Corman had truncated and added new material to, released as Battle Beyond the Sun in 1962.

Both Nebo sovyot and I Was a Sputnik of the Sun explore a future when humanity has conquered the moon and much of space in Earth’s immediate vicinity. Both films feature references to space stations and lunar laboratories, but Nebo sovyot backed this up by actually showing these, while in I Was a Sputnik of the Sun they largely remain off-screen. In Nebo sovyot Soviet cosmonauts compete with each other to be the first on the surface of Mars, while I Was a Sputnik of the Sun is obsessed with the pseudo-scientific idea of “dead zones” in space. While we know these theories to be rubbish today, they did have some foothold in the astronomical debate of the USSR at the time the film was made, be it that they were dismissed by most serious scientists. However, in the context of the movie, conquering these dead zones is the key to explore further into space.

While science fiction films were allowed a little more leeway in the late 50s Soviet cultural climate, the output still had to adhere to certain standards in order to pass censorship. For one thing, of course, they had to portray socialism and the Soviet Union in a positive light. But especially in the era of the space race, these films were often also required to both promote the Soviet space program (which swallowed up quite a lot of money) and inspire younger generations to become interested in space exploration. I Was a Sputnik of the Sun neatly ticks all boxes.

In fact, the movie feels like it was made particularly with a young audience in mind, as it starts very much like many children’s films did at the time, with an on-screen narrator telling the viewer that he is going to tell them a story. The narrator (the film’s protagonist Andrey) then lingers for quite a while on that night in his adolesence when he finds the strange videotapes, before going on to narrate himself as an adult.

The film is chock-full of narration, not only explaining things that might be difficult to explain with dialogue, but also stuff that could easily have been integrated into into lines. That the film often feels more like an educational film employing the tropes of documentaries, rather than a dramatic feature film, is no great surprise, as all central artistic forces behind it were documentarists, rather than feature film makers. The film was produced by Mosnauchfilm, which specialised in documentaries and educational films. Director Viktor Morgenstern has no other IMDb credits, but was in fact a highly prolific documentary filmmaker with a career spanning between 1930 and 1978. The picture’s two screenwriters, Vladimir Kapitanovsky and Vladimir Schreiberg, were also merited science and documentary writers. Both cinematographers on the movie were also documentarists. In other words, not a single person involved in the artistic process had any experience with feature films.

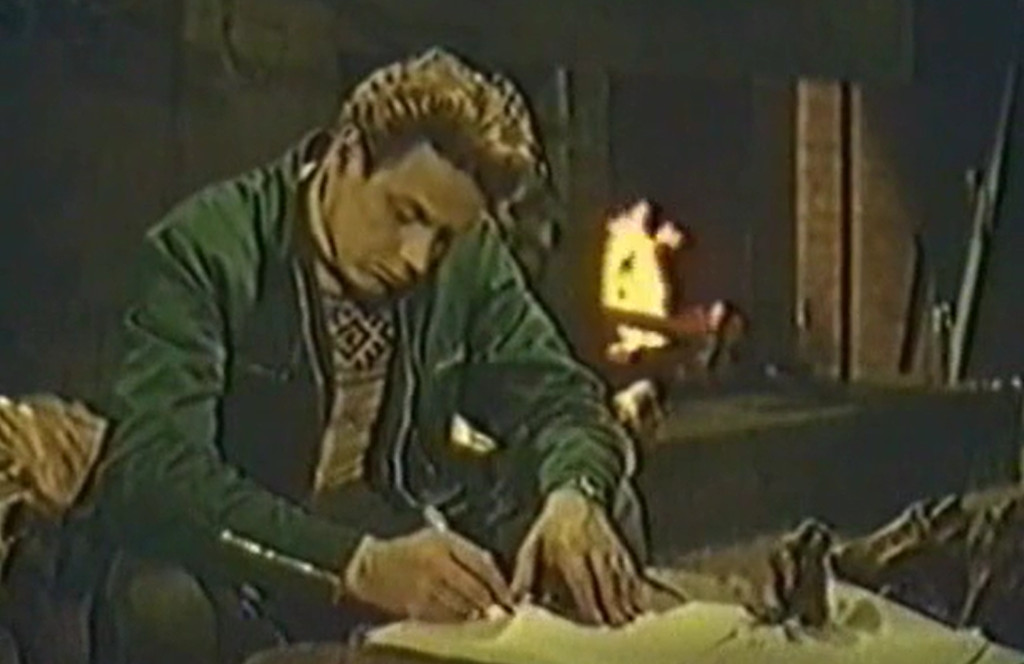

Unfortunately, this shows in the result. Neither screenwriters nor director have a feel for how you create an engaging cinematic drama. There’s too much narration, too much exposition and too much scientific techno-babble, some of it legitimate, other complete pseudo-science. While it is only 66 minutes long, it feels stretched and plodding. The characters are simply placeholders for the advancement of the plot and lack anything resembling personalities. Their only feelings seem to be an unwavering commitment to advancing progress, humanity and the Soviet creed. This, of course, was unfortunately something of a staple in lesser Soviet films of the era, but in I Was a Sputnik of the Sun it is taken to the extreme. Even when Andrey finds out that he has been lied to all his life about who his father is, his only reaction is pride and a sense of duty. The acting is not bad as such, and both Pavel Makhotin, as Andrey, and Vladimir Emelyanov, as Kalinin, occasionally help to elevate the movie above its stilted script, particularly in their scenes in space. Young Andrei, played by Anatoliy Shamshurin, is also effective in his role. An interesting tidbit is that Anatoliy Shamshurin was the real-life son of Georgiy Shamshurin, who plays Andrey’s stepfather – leading to the odd situation that Andrey has a familial resemblence to his step-father rather than to his biological father. The film also feature popular comedic actor Georgiy Vitsin as a scientist.

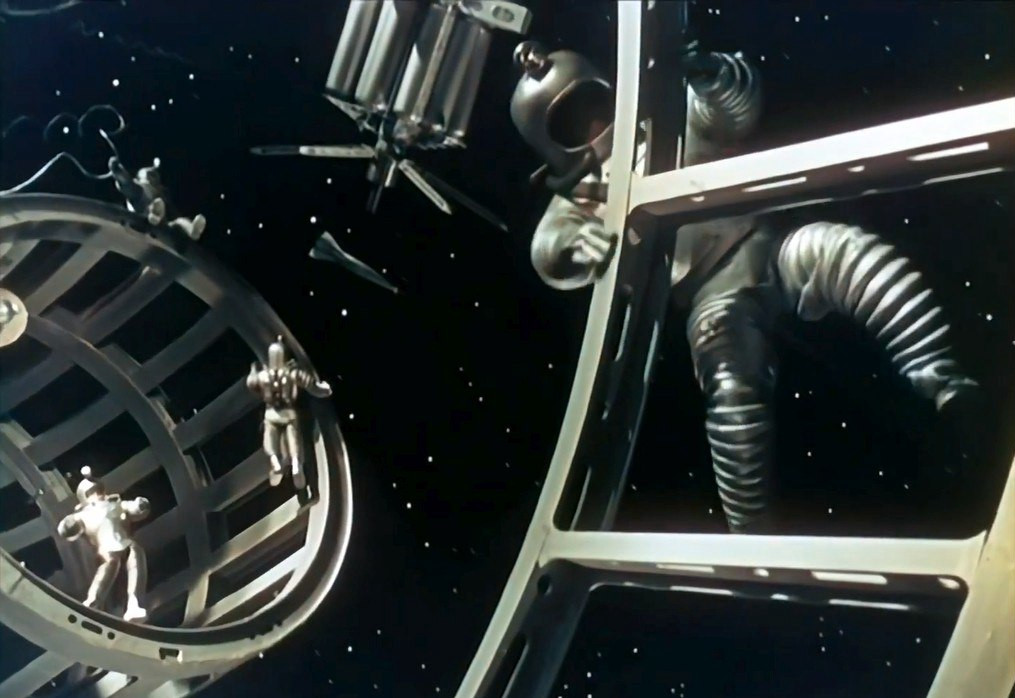

There are a couple of stand-out scenes – that are occasionally also well filmed. In particular the above-mentioned episodes depicting the two cosmonauts during their space flights are quite tense, and partly shot from an interesting dashboard angle, increasing the feeling of claustrophobia. There’s also a rather fun scene with the monkey as a test “pilot” for the rocket, which is very well executed, but like so many other scenes, drags out for too long. As John Westfahl writes at the Science Fiction Encyclopedia: it’s interesting that the filmmakers prediced that the Soviets would be using monkeys as test passengers in space, when the reality was that the USSR would come to use dogs, while it was the Americans that used monkeys.

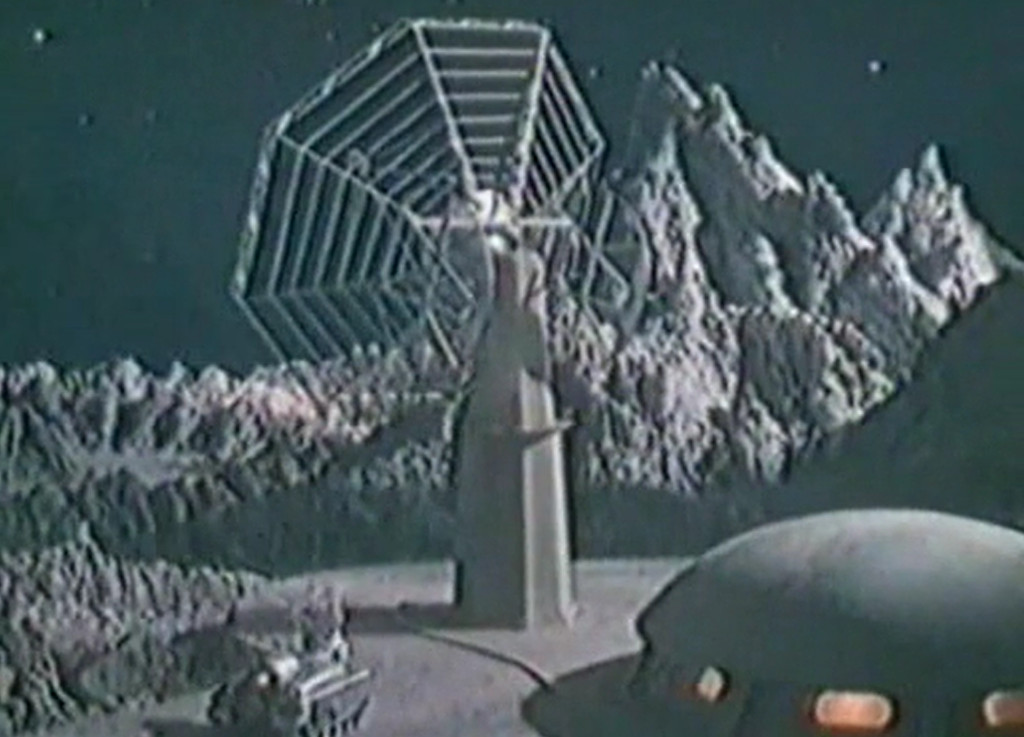

The film’s moderate budget shows. Apart from a couple of location inserts, it is wholly studio-bound, and almost completely takes place in cramped rooms. The visuals of the film, however, are its highlights. Granted, the only copy available for home viewing is a rather degraded one, but the colours have been reasonably well preserved, even if it is quite grainy. First of all, there is the typical greenish tint ubiquitous to the Soviet Svema film film stock, which alone gives the movie a retro artful feeling. But the picture also makes very good use of colour schemes and floods many scenes with gel-coloured lights, as well as uses colour selectively to highlight gauges, monitors and dials. And now I haven’t even mentioned the animations, which we’ll get to later.

The design of the film is not bad either. Granted, the designs of spaceship interiors and exteriors, as well as the various control rooms and gadgets that show up during the course of the picture, do not stray far from the typical visuals seen in both pulp magazines or Western SF movies. But they are generally well executed, and there is some pretty good model work. It’s not on par with, or nearly as prevalent as in Road to the Stars or Nebo sovyot, but of a higher standard at least than what was on display in the barrage of low-budget SF movies coming out of Hollywood at the time. The special and visual effects involvning the rocket takeoff and the separation of its three stages are very well realised.

There are not that many futuristic gadgets on display, but we do get an anticipation of both home video viewing (on a gigantic machine) and video calls, not that this was revolutionary in any way – video phones had been predicted sine the 19th century.

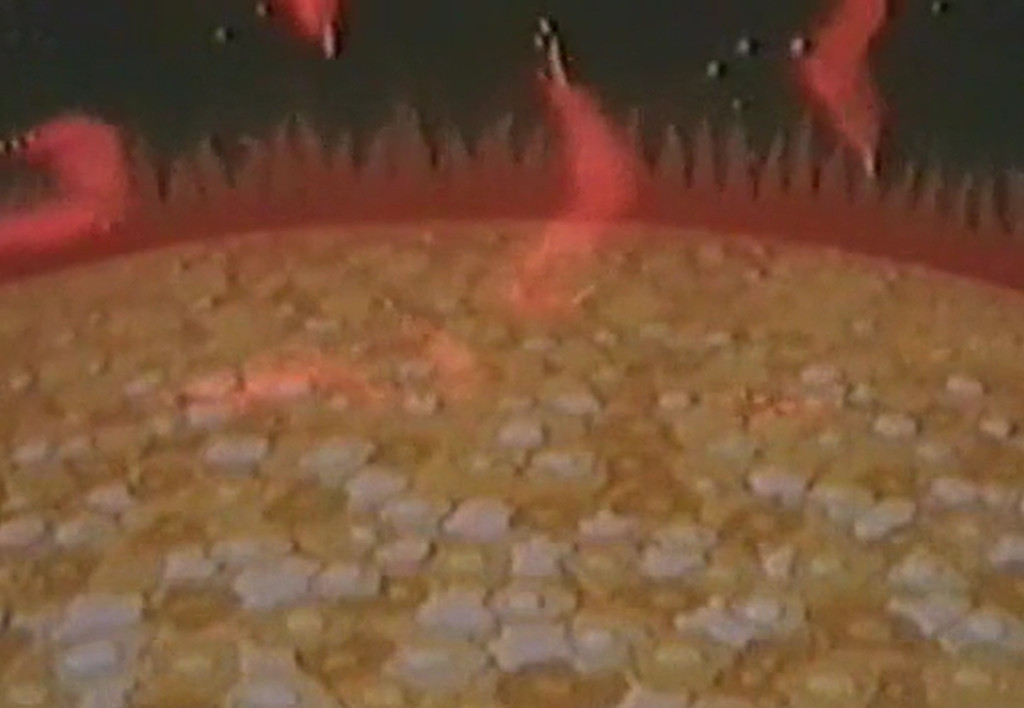

A very substantial part of the movie is taken up by animation. Some of it is purely intended for educational purposes, and made in the sort of half-cartoonish way that was common in educational films. But much of the animation is also used as visual effects, illustrating space radiation and the mysterious forces of the dead zone. These animations sometimes go on for a good minute or even longer, and are beautifully rendered. Mind you, if you throw a dart at any pre-1967 science fiction movie you have a 50-50 chance of hitting one that is claimed to have inspired 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). But knowing that Stanley Kubrick looked closely at many European and Soviet films for inspiration, it is more than likely that I Was a Sputnik of the Sun might have passed his desk. However, in the 1959 film these animations, evocative and creative as they are, often outstay their welcome. The animations were all produced by Soyuzmultfilm, the Soviet equivalent of Disney, although the company focused strictly on animation. The animations were directed by one of the godfathers of Soviet animation, Yuri Merkulov. Despite a 20-year crisis following the fall of the Soviet Union, Soyuzmultfilm still exists today and up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine produced films that were distributed internationally and received worldwide acclaim, such as the 2018 animated feature-length stop-motion film Hoffmaniada.

I might have cut I Was a Sputnik of the Sun some more slack had it been an edutainment film. However, as it is, it is clearly meant as a feature film, and with that also comes higher expectations on aspects such as drama, pacing and character development, areas in which the movie underachieves.

However, it is an interesting artefact from a specifik place and time, and as such well worth digging up for anyone interested in Soviet science fiction, but also in how people in the Soviet Union viewed a possible future. While many of the films released by the Soviet cinema machinery had propagandistic intentions, I think Western commentators are often too quick to simply dismiss storylines that explore socialist futures through sometimes rose-tinted glasses as just propaganda vehicles. We often forget that the Soviet Union didn’t promote socialism for socialism’s sake. While most of the promises that the USSR held in regards to a better world for each and everyone were brutally crushed under Stalinism, there were still many that held hope that international communism would eventually bring about a better world. These sentiments were also echoed in Soviet films.

Initially when watching the beginning of the film, I was confused. The opening credits end with the numbers 1959 splashed over the entire screen, so I assumed the film was set in that year. But then grown-up Andrey listens to the radio, and we hear the annoncer yap on about yet another flight to the moon, and then Andrey tells us he is going to start his story in his own childhood. This is when I reaslised that “1959” simply referred to the year the film was made. The movie itself is set in some unspecified near future, when, presumably, international communism has triumphed and helped bring peace and prosperity to mankind. There is no talk in the film about ideological clashes, wars or the threat of Western capitalism. On the other hand, socialism or communism as such do not play into the plot of the movie at all – there’s just the obligatory praise for “Soviet science” popping up here and there in the picture.

Instead, the film is an interesting artefact from the beginning of the space race. Sputnik had been launched in 1957, and since then more Soviet and American satellites had started to orbit the Earth. Now the race was on to send the first man into space – an as we know today that was to be Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who in 1961 accomplished the first orbital space flight. On both sides of the Iron Curtain, the first tentative steps into space held both utopian promise and dystopian threat. Western movies tended to latch on to the dystopia, while their Soviet counterparts envisioned a utopia. As far back as the early 20th century the father of the Soviet space program, rocket scientist and author Konstantin Tsiolkovsky had written fictional stories about humanity’s conquest of space, describing with often surprising accuracy a network of satellites and space stations orbiting the Earth, the work of astronauts and scientists on board the stations, their space suits, technology and means of survival. Tsiolkovsky’s vision informed much of Soviet science fiction to come, and much of what is described in I Was a Sputnik of the Sun – the satellites, stations, space laboratories and shuttle flights to the moon – came directly from his writings.

The movie employed two technical consultants (one was Vladimir Komarov, who later became a decorated cosmonaut), who no doubt spoonfed the screenwriters much of the official vision for the USSR’s space program (but left out any mention of any military use of space technology). It is interesting looking at this rosy and (intentionally) naive vision of a near future, where space travel is seen as almost mundane, and the technology in space being used to benefit mankind. Of course, much of it has come true, especially the way in which so much of our daily lives are dependent on satellite technology. But it it also amusing, in hindsight, to watch these 50s films and be reminded of the fact that many believed that by the end of the 20th century we would have daily moon shuttles, a vast network of inhabited space stations and colonies on the moon and Mars.

That is not to say that I Was a Sputnik of the Sun doesn’t involve propaganda. However, this was not a movie made in order to promote communism, but rather a movie to promote (communist) space exploration and the Soviet space program. The message that is pushed through the entire film is that humanity’s conquest of space is crucial for the advancement of science, technology, and for the betterment of the human race, and that the people involved in this endeavour are heroic pioneers for a brighter future. Thus, Kalinin and Andrey are painted as true patriots by shouldering the duty of sacrificing themselves in the name of progress. Interestingly enough, this sentiment mirrors the one in the subject of my last review, the UK/US co-production First Man Into Space (1959), in which the closing line, as spoken by Carl Jaffe is: “The conquest of new worlds always makes demands of human life. And there will always be men who will accept the risk.” But while the sentiment of space exploration as an advancement of science, knowledge and a better tomorrow were certainly held by many scientists and even a few politicians and ideologues, the space race, of course, wasn’t fuelled by such noble intentions. First of all, it was a matter of prestige between the two blocs in the cold war – Sputnik was a huge PR win for the USSR, demonstrating that the Soviets had the means to put satellite in orbit that could potentially fly over any western city, nuclear arsenal or other strategic position. Which leads to the second factor: military power. In the 50s, there were still looming fears that either bloc could use a satellite or the moon as a launching platform for nuclear missiles – or utilise space in other ways in order to gain a military advantage. So or strategic geopolitical and military reasons, it was as important for both blocs that their populations whole-heartedly supported robust financing of their space programs. And that’s why governments on both sides of the pond supported and/or produced these kind of movies.

I Was a Sputnik of the Sun is not the place to start if you’re getting into Soviet science fiction movies. A minor picture in all regards, it uncomfortably straddles the gap between edutainment, propaganda and science fiction drama, not quite succeeding in either category. It is interesting as a historical artefact, and for its many evocative animation sequences. Worth checking out for its visuals and for a look at its exploration of the fringe theory of dead zones in space, but if you are looking for an exciting adventure or engaging drama, you will certainly be disappointed.

Reception & Legacy

After quite an arduous search, complicated by AI tools that constantly gave me false information and sent me on wild goose chases, I have concluded that there are no readily available contemporary reviews of I Was a Sputnik of the Sun to be found online.

In fact, there are very few reviews of this film to be found anywhere, from any time. The only Russian-language review I can find, apart from short comments on IMDb-like film sites, comes from Nikolai Troitsky’s Livejournal account, where he laments the film’s rudimentary and naive effects, as well as the sluggish script: “This is like a feature film made by documentarians, not so much naive as boring”.

The anonymous author of the blog The Silver Scream is likewise not impressed, even if she gives some credits to the visuals: “Unfortunately, it’s not an overly good film or even an interesting one. It is slow and talky. Even the story is not all that fun.”

The lengthiest and best review of the movie I can find comes from Mark David Welsh. He compliments the “decent miniature spaceships” and “the pleasing sight of women at the consoles in mission control”, as well as the effort to convey the immensity of space. However, he writes: “Unfortunately, what’s missing here is any real human drama. The cast is stoic, and the characters resolutely anonymous, as if director Morgenstern was afraid that any random expression of human emotion would undermine the realism of his story. What remains interesting is that unbridled optimism, showcasing a future where space conquest was just around the corner.” he concludes: “An interesting time capsule but offering precious little in the way of entertainment”.

Finally, there’s Gary Westfahl’s write-up at the Science Fiction Encyclopedia. Westfahl points out that the film is interesting inasmuch that it is one of the few movies of the era that suggests the importance of studing the sun, rather than the moon or Mars, and because it anticipates that unmanned, robotic probes, rather than manned space missions, would play the central role of gathering information about our solar system. He concludes that “while it is no masterpiece, the acting and special effects are better than some observers report”.

There is some confusion over this film. For example, older entries, like Westfahl’s, sometimes report this movie as a black-and-white film. However, I suspect that a b/w version was produced for television, and that it is this TV version that has been available for viewing for a long time, until an original colour version showed up on the market. Furthermore, IMDb has an entry for a 1961 film called Перед прыжком в космос (Pered pryshkom v kosmos, “Prior to the Leap Into Space,”). The IMDb credits feature a truncated credit list, but the credits on display are all for people involved with I Was a Sputnik of the Sun. This has led some to speculate that the 1961 entry is just a mislabelled entry for I Was a Sputnik of the Sun. However, in my afore-mentioned hunt for a review, I was able to dig up a plot synopsis for Перед прыжком в космос, and from that it is clear that it was indeed a separate film, produced by the same company with the same writers, director and crew. The 1961 film seems to be a similar edutainment film about preparations for the first manned space flight, coinciding with Yuri Gagarin’s first orbital flight.

Cast & Crew

While the writers and director of I Was a Sputnik of the Sun are not uninteresting in and of themselves, they are not perhaps so much so to the readers of this blog, as they worked mainly in the realm of documentary film.

Director Viktor Viktorovich Morgenstern was born in 1907 in Russia and studied cinematography. He spent most of his career making documentaries and educational films on a wide range of topics, as well as military instruction films during WWII. Morgenstern was also the editor of the magazine Наука и техника/Nauka i tekhnika (“Science and Technology”), and it was probably his strong background in science that got him assigned to I Was a Sputnik of the Sun.

Screenwriter Vladimir Kapitanovsky was likewise a screenwriter of documentaries, on different topics, like the latest advancements in Soviet agriculture. However, after writing I Was a Sputnik of the Sun, Kapitanovsky partly specialised in space documentaries, some of which he directed himself. Little is known about co-writer Vladimir Shreiberg.

The trio of Morgenstern, Kapitanovsky and Shreiberg went on to make another feature film, apparently in the semi-documentary style of I Was a Sputnik of the Sun, released in either 1960 or 1961, according to different sources, about the first orbital space flight. Little information is available about this film online.

Of more interest here are lead actors Pavel Makhotin and Vladimir Emelyanov, playing Andrey and Kalinin, respectively. Both Makhotin and Emelyanov were primarily stage actors who transitioned into film in the 50s – I Was a Planet of the Sun (1959) was Makhotin’s screen debut. He continued his career combining stage work with film appearances, mainly in minor roles. Makhotin appeared in three science fiction movies. He played the lead in I Was a Sputnik of the Sun (1959) and had minor roles in both the well-reputed but obscure Den gneva (1985) and the less well-reputed but similarly obscure Sputnik planety Uran (1990).

Vladimir Emelyanov entered the film industry in 1953, and played a number of leads in now forgotten films. He had a long career in films, although never considered among Russia’s acting elite, and was mainly cast in supporting roles. Not so, however, in 1962, when he was cast as the lead in legendary Pavel Klushantsev’s science fiction classic Planeta bur/Planet of Storms, best known in the West for being mangled by Roger Corman and directors Curtis Harrington and Peter Bogdanovich – first as Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet (1965) and then as Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women. He also played the lead in I Was a Sputnik of the Sun (1959) and had a supporting role in the SF drama Sud Sumadsshedshikh (1962).

In a small role as a scientist in I Was a Sputnik of the Sun we see Georgiy Vitsin, better known to Russian viewers as one third of the legendary comedy trio Трус, Балбес и Бывалый/Trus, Balbes i Byvaliy, roughly translated as “The Coward, the Blockhead and the Expert”. The trio’s recognition stems from three movies directed Leonid Gainai: Bootleggers (1962), Operation Y and Other Adventures of Shurik (1965) and the especially famous Prisoner of Caucasus (1967). Vitsin played the coward in the trio, which seems to be a sort of Russian equivalent of the Three Stooges. But Vitsin’s legacy stretches far beyond the work with the trio. He appeared in over 200 movies, including comedy classics like The Diamond Arm (1969), Gentlemen of Fortune (1971) and Twelve Chairs (1971). He can be seen in small roles in the SF movies I Was a Sputnik of the Sun (1959) and Formula radugi (1966).

In another minor role we see Nikolai Timofeyev, whom we have actually met before here on Scifist, as the lead in the interesting but flawed propaganda piece Serebristaya pyl (1953, review), which combines a futuristic super-weapon with an exposé of racism in the United States. Timofeyev was a noted film and stage actor who appeared in over 50 movies from 1950 to 1986. He appeared in as many as four science fiction films: Serebristaya pyl (1953), I Was a Sputnik of the Sun (1959), Mechte navstrechu (Encounter in Space, 1963), an overlooked little gem that was edited into the Roger Corman movie Queen of Blood (1966) and Humanoid Woman (1981) or Cherez ternii k zvyozdam, where he had a small bit-part.

Janne Wass

Ya byl sputnikom solntsa. 1959, USSR. Directed by Viktor Morgenstern. Written by Vladidmir Kapitanovsky, Vladimir Shreiberg. Starring: Pavel Makhotin, Vladimir Emelyanov, Georgiy Shamshurin, Anatoliy Shamshurin, Nikolai Timofeyev, Georgiy Vitsin. Music: Sevastyanov. Cinematography: Oleg Samutsevich, Georgi Lyakhovich. Production design: Leonid Chibisov. Animation director: Yuri Merkulov. Produced for Mosnauchfilm and Soyuzmultfilm.

Leave a comment