A German-Finnish collaboration of the Sputnik era, this 1959 effort is light on science fiction and heavy on romance and wildlife as it unfolds the story of a scientist and his pet wolf – the latter destined to be shot into space. Beautiful Arctic footage isn’t enough to counterbalance the trite drama. 3/10

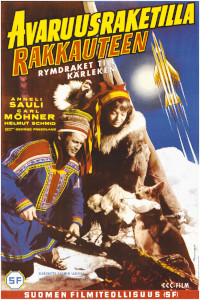

Moonwolf. 1959, Germany/Finland. Directed by Georges Friedland. Written by Friedland et.al. Starring: Anneli Sauli, Carl Möhner, Helmut Schmid, Paul Dahlke, Richard Häussler. Produced by Artur Brauner & T.J. Särkkä.

Veterinarian and wildlife enthusiast Dr. Peter Holm (or Holmes in the US version) (Carl Möhner) is spending his summer holiday in Finnish Lapland observing the wildlife when he happens upon a lone wolf cub which has survived a particularly harsh summer storm. Watching from a distance, he feels a close bond forming between him and the wolf, until the poor cub is swept away by nearby rapids.

That’s the intro to the 1959 Finnish-German co-production Moonwolf, (Zurück aus dem Weltall/Avaruusraketilla rakkauteen), which is borderline sci-fi, as it involves a wolf getting rocketed into orbit around the Earth. The film is best known for its on-location footage in Lapland, and stars German and Finnish movie stars Carl Möhner and Anneli Sauli. I have watched the dubbed 1966 American version, which is ten minutes shorter than the original.

From Peter’s summer adventure we now move forward in time for some undisclosed number of years, and we meet Peter at work as a veterinarian on a research station planning to send an animal into orbit. The animal chosen for the quest is a wolf called Wolf, which happens to be Peter’s pet. Although it isn’t explained, we assume that the wolf is the one in the prologue. Although Peter is at first reluctant, because of his emotinal bond to the wolf, he finally agrees to let his pet take the trip. Said and done: after a countdown with computers clacking, radios buzzing and fingers pushing buttons, Wolf takes to the sky. All goes well, until there is radio silence. Soon, the eggheads realise that the rocket has gone off course, and will pass over Wolf’s place of birth, Finnish Lapland, where they will be able to parachute him out of the rocket. On the plane to Finland, Peter has the opportunity to tell his boss Prof. Robert (Richard Häussler) the second part of his flashback frame story:

Flash back then to some undisclosed years in the past, again to Finnish Lapland, this time in winter. While skiing in the mountains, Peter is called upon by a grown wolf, who leads him to a young native woman, Ara (Anneli Sauli), who has fallen down a crack. Peter helps her up, and brings her to a small cabin where she resides. The wolf turns out to be Ara’s pet – she tells Peter that she rescued it from the rapids two years ago – right about the same time that Peter was last in Lapland. They deduce it is the same wolf, now aptly named Wolf (expertly played by wolfdog Hasso). After some brief flirting, Ara comes down with a cold and her fiancé Johan (Helmut Schmid) turns up to take them both to her father, who works as a weather station officer in a nearby house.

There’s a few incidents at the house, one involving Peter trying to divert a plane carrying 60 people into a storm in order for it to parachute penicillin for Ara, another one with Peter rescuing Wolf from a group of native Sapmi trying to shoot the wolf. The main takeaway from the flashback is, however, that Peter and Ara fall in love, and Ara confesses that she doesn’t really love her fiancé – who unfortunately loves her very much, and is a local Dolph Lundgren character who doesn’t take kindly to Peter’s flirting. It all ends with Peter “doing the right thing”, as he grabs his skis and says goodbye to Ara – but not after Ara has gifted him Wolf as a parting gift, seeing the bond between the man and the animal. But as Peter skis towards the sunset, he is confronted by the man-mountain Johan, who doesn’t believe him when he says he is leaving, and challenges him to a fight. After exchanging blows in the snow, Johan pulls his knife, but Peter is saved by Wolf, leaving Johan standing perplexed, as Peter takes off with his new best friend.

When the plane lands in Finland, Peter has told his story and we are back to the present – with the mission to pick up Wolf at hand. Due to bad weather, Peter and the search party can’t helicopter out to where the wolf is expected to parachute down, and the small Finnish town’s only jeep is out of order. Peter skis over to the old weather station, now manned by Ara, and asks her and (still not married) Johan to borrow their dogsled. But Ara says that it is too dangerous for Peter to go alone because of all the dangerous wolf packs, and convinces Johan to go with Peter. And sure enough, the wolves turn up. After a heroic battle, Johan is killed by the wolves, Peter finds his old friend Wolf, and Peter and Ara finally get each other with Johan conveniently out of the way. The End.

Background & Analysis

By the late 50s, the early 50s boom in Finnish cinema was coming to and end, and Finnish movie studios (all two of them) started to look outward for collaborations on bigger projects. In order to avoid any confusion as to which studio was in question, one called itself Suomi-Filmi (Finland-Film) and the other Suomen Filmiteollisuus (Finland’s Film Industry). Moonwolf was produced by the latter, who had recently found a partner in West-German studio CCC’s daughter company Alfu-Film. Alfu wanted to make a Lapland-themed movie, in line with the so-called Heimat films that were popular in Germany at the time. The Heimat films were a loosely defined genre of national-romantic films looking back toward the pre-Nazi era in West-Germany’s attempt to rebuild its identity after WWII. The word Heimat itself has no direct translation, but is a particularly German concept of a geographical and cultural home and belonging. The Heimat films were often rural in concept and many of them were set in the Alps – so making a film set in the winters of Lapland fit well with the genre, even if this Heimat was in Finland rather than Germany. For the production Alfu needed a Finnish crew for the Arctic location shooting – which consisted of around 70 percent of the whole movie.

As director and screenwriter Alfu chose French Georges Friedland (who was credited with the anglified on-screen name George Freedland), and the German dialogue was written by Johannes Händrich. The film purports to be based on Jack London’s novel White Fang, but this is pure hogwash for marketing purposes. Apart from the fact that both movie and book feature a wolf in a snowy setting, they have nothing in common plot-wise. Certainly Jack London’s books like White Fang and Call of the Wild inspired Friedland to incorporate a wilderness theme with a man-and-animal plotline. But when it comes to the interactions between man and wolf, it is more Lassie than London.

Most of the picture was shot in Finland with a Finnish crew. Finnish cinema powerhouse and CEO of Suomen Filmiteollisuus T.J. Särkkä acted as co-producer and veteran cinematographer Esko Töyri handled the DP responsibilities in Lapland as well as for shots filmed at Suomen Filmiteollisuus’ studios in Helsinki. Most of the studio work was done in Berlin with Herbert Körner as cinematographer. We know that 64 percent of the finished film was shot in Finland, because co-producer Särkkä used this as an argument when he tried to get the movie registered as a domestic product – and thus exempt from Finnish tax. However, Finnish authorities argued that a film with only German dialogue, co-produced by a German company, directed by a Germany-based director and starring mostly German actors, could not be regarded as a Finnish film. Cinematographer Esko Töyri has later said that the initial plan was for Töyri to travel to Germany to do the remaining studio work after the Finnish shooting was done, but that Alfu replaced him at the last minute with German veteran Herbert Körner – so that the company, in turn, could make a stronger argument for the film being a German production, which, again, gave them financial gains.

As for story and script, I have only been able to find the truncated 1966 US version readily available for viewing. For the US market, the film was cut down from its original 85 minutes to a B-movie length of 74 minutes. One imagines that cuts were made primarily to slower and talkier portions of the movie, removing some of the character development and perhaps some of the romantic plotline. It seems that at least one character has been completely omitted from the original cut. Finnish movie star and later director Åke Lindman is credited as a lumberjack in the opening credits, but I can’t spot him in the US edit, except perhaps for a couple of seconds when one character is chopping down a tree alongside Johan (Helmut Schmid). As Johan is also a lumberjack, I imagine that the original film had more material with Schmid and Lindman, probably rounding out the character of Johan, which has been cut from the American version. Lindman, incidentally, played one of the leads in the first ever Yeti movie, Pekka ja pätkä lumimiehen jäljillä (1954, review).

However, apart from such omissions, the US versions seems to follow the original quite slavishly, from what I have gathered – apart from the detail that the original states that the space centre is placed in West Germany, while the US version leaves the country unnamed.

As is apparent from the plot synopsis above, the movie’s dramatic arc is rather cumbersome, with the lion’s part of the action being told in two different, long, flashbacks. The story could as well have been told linearly, with the drawback that it would have shifted abruptly from wilderness drama to science fiction about two thirds through. As the movie was originally marketed with a sci-fi angle, this way of telling the story would probably have worn out the SF fans before the film’s halfway mark. With the flashback format, the science fiction elements form a frame for the movie. Nevertheless, SF fans will be disappointed. The science fiction angle is flimsy and works only as a MacGuffin – and not even a very original one. Animals had been fired into space with rockets since the late 40s, and in 1957 Laika became the first dog in space – two years before the release of Moonwolf. Basically, the only “fiction” angle of the movie is that the wolf survives the ordeal, unlike Laika.

The plot itself stretches credulity, not because of its SF matter, but because of the many extraordinary coincidences that need to occur for the plot to become a reality. Lightning doesn’t only strike twice in the same place, when Peter winds up rescuing the woman that rescued “his” wolf, but thrice, when the animal happens to be ejected from the rocket exactly above Ara’s weather station. These coincidences, of course, are part of cinema history, and we don’t mind them when the rest of the story is good, but this isn’t the case in Moonwolf. The love triangle is an odd one. Ara doesn’t love Johan and her father doesn’t want her to marry him. Nevertheless, they have somehow wound up engaged, through circumstances that are never really explained (perhaps we got more info on this in the original version, though). It’s clear from the beginning that Peter and Ara are going to end up together, but instead of letting Johan come to his own conclusions and grow as a character, he is conveniently killed off in the film’s final act. And at least in the US version, his death is pretty much handled with a shrug – despite the fact that he is the real hero of the film: he has (reluctantly) given Peter the use of his dogsled, and accompanied him as a guide. In the finale, Johan defends Peter against a wolf pack, sacrificing his own life in the process. In the US dub, Peter seems mostly annoyed that Johan’s death delays him from reaching his precious wolf.

No characters are allowed to go on any journeys in this film, apart from the geographical ones. Peter is a goodie-two-shoes from beginning to end, Ara is sweet and submissive and Johan is sullen and obstinate. One expects a change in Johan when he meets Peter in the final act, seeing as when they met earlier, Johan tried to kill Peter, and Peter let Johan live when he had the chance of killing him – not to mention that fact that Peter did right by Johan and left, instead of trying to steal Ara from him. But no, Johan is just as hostile towards Peter the second time around, for little apparent reason. Despite all the voice-over narration about the wilderness and humanity, nobody learns anything about themselves during the film, which makes the whole excercise seem rather pointless. As far as themes go, it’s difficult to pinpoint what the movie wants to say or comment on, if anything.

The highlight of Moonwolf is Esko Töyri’s beautiful photography of the landscapes and animals of Lapland. But even the stark, magnificent landscapes are diminished by the boxy format used for the DVD version of the film. The original 1:66:1 European widescreen format would have elevated the visuals, but the Sinister Cinema DVD is probably a TV rip, as it is presented in the 1:33:1 aspect ratio. Otherwise, both Töyri’s and Körner’s cinematography are unremarkable. Professional, but standard. The same goes for Friedland’s direction. Carl Möhner in the lead is an acceptable actor but somewhat bland. Anneli Sauli is pretty and lively, and while she was a talented actress, she gets little chance to show her range thanks to the script. The same goes for Helmut Schmid, who is only ever portrayed as a hulking menace. The rest of the German and Finnish cast are all adequate in their roles, and the film’s less than stellar quality is not caused by any lack of acting talent. Sauli was credited as Ann Savo, which was the moniker she used in Germany.

The film puts on display some of the Sapmi culture, and manages, with some exceptions, to avoid most of the negative stereotypes about these indigenous people that the 50s were otherwise rife with in the Nordics. The movie might have had trouble with distribution in the US in the 50s, as it portrays an interracial romance with a happy ending, but by the time of its American release in 1966 the Hays code had become practically irrelevant. Not that many in the US audiences would have been able to peg Ara as a different race than Peter anyway, as the film doesn’t mention it. In general, the film’s depictions of the Sapmi people is along the lines of a tourist brochure from the 50s rather than anything steeped in reality. It’s not offensive per se, but used as a gimmick more than anything else.

Even movies that are bad in essentially all technical and artistic categories can still get by as enjoyable if they know what they are and don’t pretend to be anything else. Such is the case with many low-budget sci-fi and monster movies. Moonwolf isn’t really bad in any category except one: scripting. It’s occasionally beautifully filmed, and competently directed and acted. Due to its mostly on-location nature, there’s nothing to complain about in terms of production values and design, and with a few well-chosen stock shots and a couple of well-enough made props, even the technical SF content is well portrayed. Script-wise, the dialogue is basically sound and isn’t marred by the clunkiness found in many Hollywood Z-movies. But the feeling one gets from the picture is that nobody really knew why it needed to be made, what audience it was supposed to appeal to and what writer/director Friedland wanted to say with it. Suomen Filmiteollisuus probably agreed to the production as it presented the company with an opportunity to have a Finnish-made film receive wide distribution in Germany, and possibly internationally. German Alfu was able to make the Finns heft most of the bill, and imagined it could easily make back their part of the budget, no matter if the movie was particularly successful or not.

The result is certainly watchable. Despite the convoluted story frame, there’s never any confusion as to the whats, wheres, whens and whys, even if the character motivations are sometimes fuzzy. The flashback framing could have functioned, had there been a clear reason for it, such as some form of mystery needed to be solved. But there is none here – the only “mystery” that the flashback reveals is why Peter is so reluctant to give up his pet wolf for space experimentation. And the answer that it ties him to Ara is answered in the film’s first 20 minutes. The wolf and its space journey turns out to be no more than a MacGuffin, and Peter’s relationship with Wolf is really only the means through which he is finally reunited with Ara. At heart this is a romance story, but the romance is awkwardly written and too flimsily presented for the viewer to care much. The movie, for whatever reason, tries to do three things at once, and fails in all three regards, making the viewer feel a bit cheated.

Reception & Legacy

The German title by which the film is known is Zurück aus dem Weltall (“Back from Space”). It was released in Finland in spring of 1959, under the bilingual Finnish/Swedish titles of Avaruusraketilla rakkauteen and Rymdraket till kärleken (“Space Rocket to Love”). Finnish press material mentioned its original German title, Zurück aus dem Weltall. However, according to the Finnish Film Archive’s website Elonet, for its German release in the fall of 1959, it was retitled as …und immer ruft das Herz (“… And Ever the Heart Keeps Calling”). Contradicting this narrative is the fact that there are surviving German posters with the title Zurück aus dem Weltall. German B-movie portal Badmovies writes that the movie was indeed released with the original title Zurück aus dem Weltall in Germany in 1959, but bombed so badly that it almost immediately disappeared from cinemas. The anonymous author at Badmovies writes that CCC re-released it in 1961, hoping to reclaim its production costs, now with the new title …und immer ruft das Herz. This time, Alfu removed all allusions to science fiction in the marketing and sold it strictly as a romantic drama. Apparently, this did little to help its success at the box office.

The film was picked up at an unspecified date by Allied Artists, edited, shortened and dubbed in English for release in 1966. By this time it was common practice especially for smaller studios and distributors to pick up foreign genre movies for US release, not seldom heavily edited and altered, but sometimes, such in this case, relatively intact. By all accounts, the film did not receive a particularly wide release in the US, as I have only been able to find one review from the trade press at the time.

The original film was promptly forgotten soon after its release, and there are no records of any TV broadcast either in Germany or Finland in the 20th century. But in 2008 the US version of the movie was released on DVD by Sinister Cinema. The original version has never been released for home viewing, probably due to its copyright legalities as a co-production between two now defunct studios in different countries. The Finnish Film Archive does have a copy, and it was shown on Finnish TV in 2011 as part of an Anneli Sauli retrospective.

The Finnish Film Archive has compiled a list of review snippets from Finnish critics at the time of the release of Avaruusraketilla rakkauteen, and if I’m somewhat critical of the movie, contemporary Finnish reviewers were no kinder.

In Swedish-language Nya Pressen daily, Eirik Udd described the movie as “a more than little naive and clumsily constructed story about German Sputniks in Lapland, where dogs, love and fisticuffs are cooked together into a not particularly tasty soup”.

Matti Savo at the left-wing daily Kansan Uutiset struck a slightly satirical note in writing: “Forgive me, but I can’t help but express a bit of Schadenfreude: we [in Finland] are not the only ones capable of making helplessly bad movies. This film, which is inspired by the Sputniks, is a German-Finnish collaboration […] and at least the Finns are not to blame for its childish and illogical nature. Esko Töyri has shot Finland’s wintry landscapes with a steady hand and our reindeers have all been up to their tasks.”

Kirsti Liivala at the movie magazine Elokuva-aitta noted that Moonwolf seemed custom-made for attracting tourists to Lapland: “the Germans have stuffed the story with as much real and imaginary tourist propaganda as possible, but it’s questionable whether this will have any pull, as the film itself is so sub-par”.

However, Finnish critics did find positive aspects as well, namely the Finnish aspects. Esko Töyri’s camera work got positive mentions in most reviews, and in Turku-based newspaper Uusi Aura, reviewer Esko Heimo opined that lead actress Anneli Sauli was “at least as good as her co-stars”. Heimo was of the opinion that the wolfdog was the best actor in the movie.

I have found no contemporary German reviews, and only one from the movie’s 1966 US release. The critic at the Motion Picture Exhibitor wasn’t any more positive than his Finnish counterparts, noting that the promised space adventure de-evolves into “a trite and rather dull romance between a scientist and a gal from the North”. The magazine wrote that the footage from Lapland “provides interesting backgrounds, but the film has little else to offer”. Performances, directions and visuals were deemed “standard”, but the script sub-par. Like Esko Heimo, the Motion Picture Exhibitor also singled out the dog as the best performer of the lot.

Modern reviews of the movie are scarce. In a 2011 write-up about the afore-mentioned Anneli Sauli TV retrospective, critic Harri Römpötti at the Helsingin Sanomat daily called Moonwolf “a somewhat silly picture”. At evening paper Ilta-Lehti, Jyrki Laelma pondered that “Jack London must turn in his grave at the thought of his work being named as an inspiration for this film”. A capsule review in German Filmdienst states: “[The] curious plot is the only noteworthy element in an otherwise sentimental and banal Heimat film”. And at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings (the only English-language review I could find), Dave Sindelar writes: “There’s a certain curiosity value to the fact that most of the movie is set in Lapland and shot in location there, but it’s certainly not enough to save this movie from the doldrums. This one is quite disappointing.”

German Badmovies has a long and very good, but unfortunately anonymous, write-up about the movie. The critic writes: “Zurück aus dem Weltall certainly isn’t what I’d call a ‘good’ film, but its quirky mix of semi-documentary nature film, love story, and utopian technology film makes it unique and one of a kind. Try as I might, there really isn’t a comparable film, and that alone makes it a worthwhile”. The critic adds: “What exactly Friedland ultimately wanted to tell us with this proud work is a secret he took to his grave”.

Cast & Crew

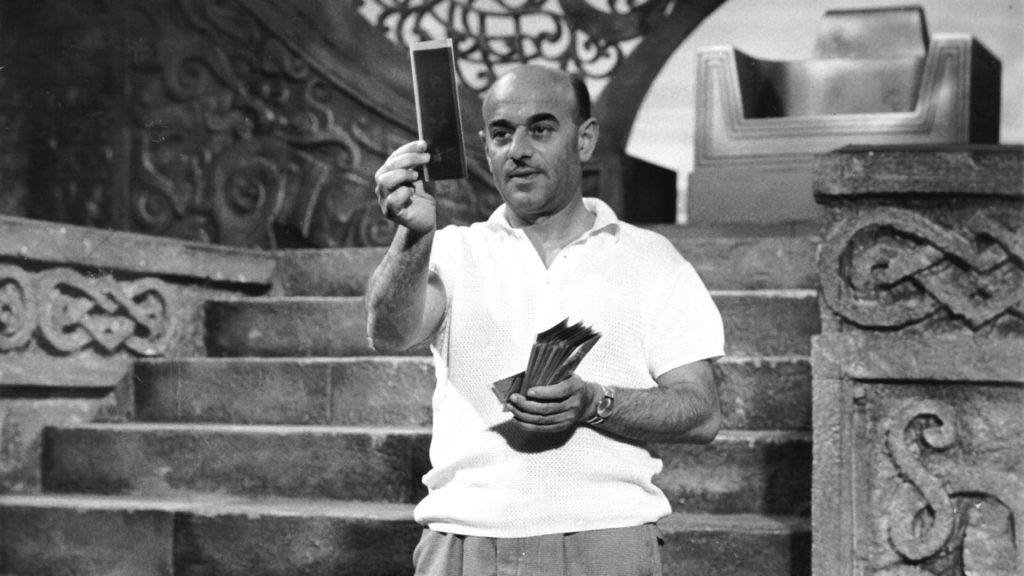

Moonwolf had three producers: German brothers Artur “Atze” and Wolf Brauner, as well as Finnish T.J. Särkkä. The Brauner brothers were the founders of the Central Cinema Company, better known as CCC Films, which was the parent company of Alfu Film, which was the nomimal production company for Moonwolf. Atze Brauner was a bigwig in German cinema, and won two Golden Globes and an Academy Award during his long career. Born in Poland, Brauner survived the holocaust when his family relocated to the Soviet Union during WWII, and after the war they moved to Germany, where Atze immediately became involved in film production, and in 1946 founded CCC Films.

The company thrived thanks to Brauner’s shrewd tactic of producing cheap but commercially successful B-movies in order to finance more artistically ambitious films. Between 1946 and 2018 Atze Brauner produced well over 300 movies, both critically acclaimed award-winners and Z-clunkers. He was instrumental in getting directors like Fritz Lang and Robert Siodmak to return to Germany from Hollywood. In 1954 he produced Siodmak’s first German film since his detours in Hollywood and France, Die Ratten, which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, and in 1959 he produced Fritz Lang’s double epic Die Tiger von Eschnapur and Das indische Grabmal, Lang’s first German films since his departure in the 30s. It was also Brauner who convinced Lang to continue his Dr. Mabuse series with The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse in 1960, which led to a string of Mabuse films in he 60s and 70s. During his career he worked with directors like Lang, Siodmak, William Dieterle, Dario Argento, Vittorio De Sica, Andrzej Wajda, Agnieszka Holland and István Szabó, but also schlock makers like Russ Meyer and Menahem Golan, as well as Jesús Franco, who was a frequent collaborator on movies like Vampyros Lesbos (1971) amd The Vengeance of Dr. Mabuse (1972).

Atze Brauner produced ten science fiction movies, of which the first was Moonwolf (1959), and the vast majority were Mabuse movies. Noteworthy are also two German-British co-productions, The Brain (1962) and Frozen Alive (1964). As an aside, Brauner seems to have liked Anneli Sauli, as he used her again in two more films, albeit in minor roles.

Toivo Jalmari “T.J.” Särkkä was a giant in Finnish cinema as the longtime CEO for the studio Suomen Filmiteollisuus (which was long one of only two commercial films companies in Finland). He produced over 200 films and directed around 50, and remains both the most prolific movie producer and director in Finnish movie history. As a director he was drawn to national romanticism and romantic melodrama, but as a producer he also had a keen eye for what the audience wanted. Särkkä was one of the driving forces behind the low-brow musical comedy style known as “rillumarei”, which in turn birthed the hugely popular Pekka ja Pätkä comedy film series (see my review of the 1954 yeti movie Pekka ja Pätkä lumimiehen jäljillä for more on this).

Särkkä started his career in 1936 and it ended with the bankruptcy of Suomen Filmiteollisuus in 1965. He produced and/or directed some of the most successful Finnish movies of the 40s and 50s. Among these were the romantic comedy Kulkurin valssi (1941), which at the time was the most successful Finnish picture in history and the first “rillumarei” movie Rovaniemen markkinoilla (1951). In 1953 he directed The Milkmaid, which propelled Anneli Sauli into stardom and made her a sex symbol. Särkkä was reluctant to adapt Väinö Linna’s best-selling WWII novel Unknown Soldier into a film, as it offended his patriotic sensibilities with its crude and realistic depictions of the soldiers in the trenches. He eventually caved in to pressure from the rest of the studio, and the 1955 movie adaptation (co-starring Moonwolf’s Åke Lindman) has since been voted annually as Finland’s best film ever by audiences. It is shown on TV every year at Finland’s independence day on December 6th. In 1956 Särkkä directed Juha, Finland’s first movie in colour and CinemaScope. As a producer and studio head, Särkkä was never known as an innovator, and tended to put popularity ahead of artistic merit. As a director, he had a preference for pathos, melodrama and bombasticism, which sometimes put him at odds with co-workers who thought his preferred style was too cheesy and overwrought (he famously clashed with house composer Toivo Kärki). Nevertheless, T.J. Särkkä’s shadow looms large over Finnish movie history. Moonwolf was his only SF picture.

Director Georges Friedland, credited here as George Freedland, is a curious figure about whom there is not much information online. Born in Paris in 1910, and likewise dead in Paris in 1993. His movie credits, while stretching from 1931 to 1989, are spotty, and his he is credited under a number of monikers. If his IMDb sheet is to be trusted, he was first credited in the movie business in 1931 as both editor and assistant director for self-exiled Soviet director Fyodor Otsep, whom he helped put together a couple of films as both German and French versions – a short-lived practice that was common during the early days of the talkies. He has a dozen editorial credits in the 30s, and half a dozen credits as assistant director and writer, and seems to have been primarily stationed in Paris during this time.

Freidland’s career seems to have been interrupted by WWII between 1938 and 1945, when he returned to filmmaking, at least briefly, again working as editor and assistant director to Otsep. He made his directorial debut in 1948 with Nine Boys, One Heart, an obscure film noteworthy only for starring Édith Piaf. However, credits are scarce during the 40s and 50s, as he only seems to have been involved in a small handful of movie productions during these decades. However, the fact that he worked with directors like Fyodor Otsep and Henri Stork is a sign that he must have had some reputation as a capable craftsman. Moonwolf (1959) was his last movie credit for 16 years. In the mid-70s he was involved in two movies, followed again by a 10-year gap. In 1985 he emerged again, this time as a writer for the French exploitation studio Eurociné, for which he wrote half a dozen films between 1985 and 1989, most of them involving Jesús Franco. These included the sci-fi The Panther Squad (1986) starring Sybil Danning, Golden Temple Amazons (1986) and two Franco movies starring Christopher Lee: Dark Mission: Flowers of Evil (1988) and Fall of the Eagles (1989), which was to remain his last picture.

Lead actress Anneli Sauli caused something of a sensation with her sensual performance in the erotically charged movie The Milkmaid (1953), only her second film, complete with full nudity. In 1954 she co-starred with Moonwolf (1959) actor and future husband Åke Lindman in the first ever film about the Abominable Snowman, the low-brow comedy Pekka ja Pätkä Lumimiehen jäljillä (“Pekka and Pätkä on the Snowman’s Trail, review), which, like Moonwolf, was partly filmed in Lapland. Another celebrated performance came in 1957 with the title role in the drama Miriam.

As TV became common in Finland in the late 50s, the Finnish movie industry suffered badly, and as roles became sparse, Anneli Sauli briefly moved to West Germany, where she made a good dozen films under the pseudonym Ann Savo – the best known are probably the horror movie Dead Eyes over London (1961) and the crime mysteries The Wizard (1964) and The Racetrack Murders. In the latter she played a Chinese character, in line with the yellow- and blackface practices at the time. She had the chance to appear alongside future Bond villain Gert Fröbe in the n:th remake of The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1962) and former American Tarzan actor Lex Barker in Dr. Sibelius (1962). She appeared in her second and last SF film in 1959, the German-Finnish co-production Moonwolf.

A scandal in 1965 concering an illegitimate child ended both her marriage to co-star Åke Lindman and, at least temporarily, her movie career. Upon returning to Finland she was shunned by the movie business and only got a few TV roles or film cameos. However, she found work on stage, as she was recruited to the Joensuu City Theatre by legendary demon director Jouko Turkka in 1971. In the 90s her past “sins” were forgiven and forgotten and Sauli once again started appearing in films and TV shows, aided by a Finnish film boom at the turn of the millennium.

In 2024, two years after Sauli’s death, documentary filmmaker Saara Cantell released an interview-based documentary about the actress, Annelin aika (“Anneli’s Time”), including deep-dive interviews with Sauli. In it, Sauli talks about being discriminated and harrassed (sexually and otherwise) in the Finnish movie business, partly because of her being half Roma, and partly because of her reputation as a sex symbol. She also says that controversial theatre director Jouko Turkka saved her career. Sauli was a lifelong communist, and in the 2000’s she unsuccessfully ran for parliament twice on the platform of the then minuscule Finnish Communist Party.

While not quite as famous in Germany as Anneli Sauli was in Finland, Moonwolf lead actor Carl Möhner was nevertheless a noted movie star in his adopted home country (he was Austrian by birth). He made his debut in 1953, and got noticed in a key role in the classic French crime drama Rififi in 1955. He played leads or co-leads in a handful of German dramas in the latter part of the 50s, before relocating to the UK, where he acted in a half dozen films, including leads in The Camp on Blood Island (1958) and Sink the Bismarck! (1960). In between he also appeared in his only SF, Moonwolf (1959), in the lead opposite Finnish actress Anneli Sauli and wolfdog Hasso, and wrote, directed and starred in the action movie Inshalla: Razzia am Bosporus (1958).

In the 60s Möhner became a mainstay in productions all over Europe, some more prestigious than others. He had a brief turn as a bona fide action hero in Italian and German exploitation films in the mid-60s, starring in spaghetti westerns, peplums as well as vampire and crime movies. By the 70s Möhner was already segueing out of acting into a second career as a painter, but he turned up occasionally in productions like the Nazi sex comedy She Devils of the SS (1973), the action movie Callan (1974) and the crime thriller La Baby Sitter (1975).

Playing the unthankful role of Johan in Moonwolf (1959) is German actor Helmut Schmid (not be be confused with the later chancellor of Germany, Helmut Schmidt). Like with the rest of the characters in the movie, Moonwolf doesn’t give Schmid any opportunity to show what he was actually capable of, even if he is a formidable presence, and bears a striking resemblence to a later Dolph Lundgren. Like Möhner, Schmid had a solid background in the theatre, and never left the stage even when his film career took off – he eventually became a theatre director as well. From the mid-50s to the mid-60s Schmid was a mainstay in German mainstream movies. Although never among the country’s brightest stars, he worked steadily and successfully in pretty much every genre, often in co-leads or large supporting roles, not seldom opposite his wife Liselotte “Lilo” Pulver. In the mid-60s he transitioned from film to TV, where he worked until the late 70s, after which he focused on the stage. Schmid also appeared in a number of British and American movies filmed in Germany – most noteworthy in a co-lead capacity in the war/heist movie A Prize of Arms (1962). He had a bit-part in Billy Wilder’s One, Two, Three (1961) and had small supporting roles in Commandos (1968) and The Salzburg Connection (1972). His only SF movies were Moonwolf (1959) and the magnificently titled 1959 movie Die Nackte und der Satan (“The Naked and the Satan”), which got a US release under the significantly less scintillating – although more thruthworthy – title The Head – in which he played a lead.

Paul Dahlke, playing Ara’s father in Moonwolf (1959) was one of Germany’s most revered character actors both before, during and after WWII, and was one of the few movie stars whose career doesn’t seem to have been affected by the fact that he “collaborated” with the Nazis. In general, artists and actors who kept working under and benefitted from the Nazi rule faced serious career hurldes after the ending of the war. He was awarded the German Film Award (the Lola) in 1957 for his work in the Thomas Mann adaptation Confessions of Felix Krull, and a lifetime achievement award in 1974. Like Schmid, Dahlke’s only SF movies were Moonwolf (1959) and Die Nackte und der Satan (1959).

Moonwolf was the last film of Ingrid Lutz, a popular supporting and sometime lead actress in the 40s and 50s. In the movie she plays a character called Ilona, which I must confess to having no recollection of.

Much could be written about Finnish Olympic footballer, actor, director, writer and producer Åke Lindman, who can also be glimpsed in a number of Hollywood movies filmed in Finland. But because he is almost entirely cut out from the only available version of Moonwolf, I direct you to my review of Pekka ja Pätkä lumimiehen jäljillä if you are interested in knowing more.

Cinematographer Esko Töyri won the Finnish “Oscar”, the Jussi award, for best cinamatography thrice, and also directed a handful of movies.

Janne Wass

Moonwolf. 1959, Germany/Finland. Directed by Georges Friedland. Written by Georges Friedland, Johannes Hendrich. Starring: Anneli Sauli, Carl Möhner, Helmut Schmid, Paul Dahlke, Richard Häussler, Ingrid Lutz, Horst Gentzen, Åke Lindman, Inken Deter, Paavo Jännes. Music: Peter Thomas (orig.), André Brummer, Albert Sendrey (US). Cinematography: Esko Töyri, Herbert Körner. Editing: Rudolph Cusumano, Jutta Hering. Art direction: Aarre Koivisto, Max Bienek. Sound: Kurt Vilja, Erwin Schänzle. Producer by Artur Brauner & T.J. Särkkä for CCC Films, Alfu Film and Suomen Filmiteollisuus.

Leave a comment