Trapped between gender wars, generational wars, cold wars and fierce optimism, the science fiction film finally burst onto Hollywood in the 1950’s. While much of it seems quaint today, true masterpieces were produced during the decade, often on very modest budgets.

The 1950s was a period of conflicting forces in the world. Coming out of WWII, rebuilding, global economic cooperation, technological advances and a growing population gave birth to an economic boom and rapidly rising standards of living. Many parts of the world, especially the global North, saw the emergence of the economically secure middle-class that could afford to buy houses, cars and material goods. Home appliances and TV dinners meant more time for leisure and recreation, and the ever-increasing production of goods and gadgets that were affordable to the working man and woman created an enormous optimism – the future, in many senses, looked like a Brave New World.

On the other hand, the growing tensions between the East and the West developed into a cold war, with an Iron Curtain drawn between the Soviet Union and the European countries in its field of influence, on the one hand, and on the other hand, the capitalist European countries. In USA in particular, the fear of communism seemed to permeate every corner of society as the Red Scare increased. As Americans were told to check for reds under their beds before going to sleep every night, a culture of paranoia and fear spread over the country – fear both of communist infiltration, and of being accused – justly or unjustly – of Unamerican Activities because of leftists sympathies or criticism against the government.

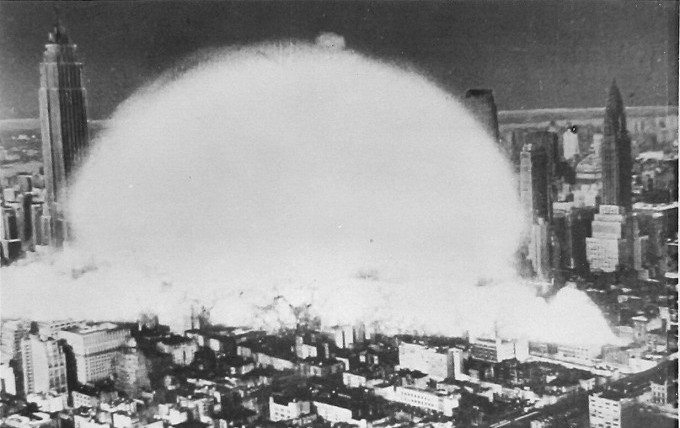

And of course, the threat of nuclear war loomed dark over the world – at least in the imaginations of millions of people, as the true aftermath of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki became clearer.

Perhaps the ideological and social movements of this era were particularly well suited to be presented within the field of science fiction, or perhaps science fiction became popular independently of these movements – we shall never have a definitive answer. But whatever the case, the 50’s seemed like a decade made for SF – both in literature and on the big and small screen. Interest in the possibilities of science and technology peaked with the rapid new development in these fields, bringing science fiction out of its nerdy shadows into the mainstream. Conversely, the fears of the decade were ably portrayed in stories like Philip Wylie’s Tomorrow! (1954) and Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957).

1939–1942 is sometimes considered the Golden Age of written science fiction – based on the astounding number of iconic stories published – primarily – in John Campbell’s groundbreaking science fiction magazine Astounding. However, people like author Robert Silverberg have argued that the 50’s was the real Golden Age, due to the founding of over 40 different SF magazines in the US the decade. While Astounding had been the only serious option for serious SF writers in the 40’s, in the 50’s came the rise of two fierce rivals – The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Galaxy Science Fiction, whose pages were filled with experimental, wild, genre-pushing stories by young authors escaping Campbell’s narrow editorial rules regarding a focus on science and plausibility. The decade also, in a sense, saw the birth of the science fiction novel as a consumer product. While SF novels had been published for decades, even centuries, modern SF, such as was found in the pulp magazines, had not previously been seen as a marketable mass commodity by US publishers. In the 50’s, however, both Doubleday and Ballantine started releasing new science fiction novels in hardback.

Authors like Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, L. Sprague de Camp, Theodore Sturgeon A. E. Van Vogt and Clifford Simak had already established themselves as the vanguard of the new wave of SF in the 40s’. But the 50’s saw an onslaught of newcomers vying to push the old masters off their thrones, people like Jack Vance, James Blish, Poul Anderson, Damon Knight, William Tenn, Frederik Pohl, Arthur C. Clarke, C. M. Kornbluth, Ray Bradbury, Alfred Bester, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Philip K. Dick, Robert Sheckley, Philip José Farmer, Andre Norton and many more. Instead of buckling under the competition, the old-timers simply put in a new gear, and produced some of their best work during the 50’s.

The Space Race is generally seen as having begun in October 4, 1957, when Soviet scientists launched Sputnik. However, in science fiction it had begun decades earlier. In fiction, people had created moon rockets as far back, at least, as the 17th century. The early 20th century was full of people travelling in outer space, in more or less realistic fashion. And by the 50’s, they also started leaving the Earth’s atmosphere en masse on the movie screen. It all began with Hungarian immigrant and puppeteer George Pal, who convinced producer Robert Lippert to join him in bringing the first American moon flight movie – in colour – to the big screen. Destination Moon (1950) was the nudge that put the ball rolling.

But it wasn’t only man’s reach into space that interested readers and moviegoers, but just as much who might be reaching for us from outer space. 1951 saw the dawn of the alien movie with two timeless classics – one featuring a benign alien, and the other a hostile one: The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Thing from Another World.

All three of these films were also highly political. George Pal was anti-communist in the extreme, and Destination Moon sees the conquest of space primarily as a military project – beating the Russkies to the moon as a possible missile base at any cost. Christian Nyby’s and Howard Hawks’ The Thing from Another World is also mired in red scare politics. The monster from outer space is a clear analogy for communist infiltration, and the final line, calling on the audience to “keep watching the skies” is a thinly veiled prompt to “keep checking under under your beds”. Conversely, with The Day the Earth Stood Still, producer Julian Blaustein and director Robert Wise introduce us to an alien who warns the US populace of continuing the arms race, and instead reach out over the Iron Curtain in the spirit of friendship and cooperation.

These two opposing views would continue to be at war with each other during the first half of the decade in particular, with anti-Soviet sentiment reaching outright hysterical proportions in films like The Red Planet (1952) and Invasion U.S.A. (1953). But they were also joined by films that have at least by some been interpreted as criticism against McCarthyism and the spreading of red scare paranoia, such as It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

In few countries was the aftermath of WWII felt as acutely as in Japan, first devastated by the American nuclear bombings, and then humiliated by a US occupation. The Japanese film industry was booming in the early 50’s, with the rise of a new generation of filmmakers, heavily inspired by American movies. Most prominent, of course, was Akira Kurosawa, reshaping the stories of the American West in feudal era Japan. One of Kurosawa’s acolytes was Ishiro Honda, who had himself served in the war. In 1954, following a fatal American nuclear test off the coast of Japan, Honda channeled all the outrage and fear of the nuclear bomb, as well as the harrowing memories of the bombing of Tokyo, into the iconic monster of Godzilla, in the process giving birth to a whole new film genre: the kaiju movie.

Godzilla, of course, was heavily inspired, not only by the classic King Kong, but by another American film from 1953, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, following the hunt for a giant prehistoric reptile wreaking havoc on New York – the first major stop-motion animation work by legendary Ray Harryhausen. The movie set the tone for another one of the major themes in 1950’s SF film – the giant monster. It was followed in 1954 by the big-budget production Them!, which ushered in the era of the giant bug movie. Meanwhile, also in 1954, Jack Arnold, hot off the success of It Came from Outer Space, made The Creature from the Black Lagoon, restarting Universal’s monster franchise, and inspiring numerous imitators not only in the 50’s but in decades to come.

Things were moving outside of the US as well. Japan not only produced kaiju films, but a whole slew of interesting science fiction yarns depicting invisible men, weird visitors from other planets, superheroes, robots and futuristic submarines. British movies, previously averse to science fiction, also latched on to the trend. Many early entries were fascinated by the possibilities of faster-than-sound aviation and often contained elements of the spy thriller, but a game-changer was the immensely popular TV series The Quatermass Experiment in 1953, following a team of scientists battling an alien “virus” brought home in the body of an astronaut. Quota quickie company Hammer bought the rights to the story, and created their own movie version, highlighting the horror elements and leaning into the British censors’ X-rating with The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), which became a resounding surprise hit, and pushed Hammer into breaking new ground for the horror movie genre with The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957.

Other countries also made their first forays into science fiction films – like Egypt, Turkey, India, Finland, Norway and Sweden. As a rule, output from these “newer” producers of SF cinema tended to be spoofs and comedies, rather than serious cinema. An exception was Mexico. Although not new to SF movies, Mexican cinema saw an explosion of genre fare in the 50’s largely thanks to the emergence of the luchador film. In the beginning, these films that portrayed the masked wrestlers, in particular superstar Santo, as superheroes, adhered closely to the formula set forth by US detective serials, but over time the luchador film gained increasingly outlandish features, with the heroes fighting off werewolves, robots, zombies, vampires, mummies and supervillains. The Soviet Union produced few SF films during the era of Soviet realism, but after the death of Stalin and the “de-stalinization” of the Union, a few SF movies started to trickle out of the country – culminating at the end of the decade, when the space race was officially on.

Outside of the geopolitical tensions and the race to space, one major force influencing movies at the time was the rise of the teenager and of youth culture. Rock music made its entrance onto the scene in the mid-50’s, and the emergence of a young generation, now for the first time with time and money of their own, led to something resembling a generational war, as the youngsters strived to break out of the conservative values permeating 50’s middle-class existence. Teenagers invaded coffee shops and ice cream parlors, shopping malls and drive-in theatres, when they weren’t driving their new cars into lovers lane to make out. Juvenile delinquency saw a sharp peak in the US in the early 50’s, prompting a congressional committee to crack down on the moral decay of youth culture. The misunderstood, raging teenager became the stuff of headlines, and new movie stars like Marlon Brando and James Dean gave a voice to the young generation. Dean’s Rebel Without a Cause and Giant became watershed moments in American culture, and prompted Hollywood studios to cash in on the trend with an endless stream of films set in juvenile prisons, high schools and jive joints. It was American International Pictures, home of Roger Corman, that first married the teenage film with science fiction with I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957), giving rise to a flood wave of teens battling monsters and aliens in the latter part of the decade,

Speaking of AIP, one would be amiss if one didn’t mention the small exploitation studio’s remarkable output and influence creating low-budget science fiction films that often exceeded their meager budgets thanks to innovative guerilla filmmaking, outrageous ideas and a team of remarkably competent screenwriters and directors. While often dismissed as low-budget trash at the time, the films of directors like Fred Sears and in particular Roger Corman have since undergone a re-evaluation and many are considered cult classics today.

Producers and directors like Jack Arnold, William Alland, Fred Sears, Roger Corman, George Pal, Ivan Tors, Curt Siodmak, Jack Pollexfen, & Aubrey Wisberg, Kurt Neumann as well as Jack Rabin & Irving Block all helped define the science fiction movie of the 50’s. But the decade also gave the movies its first bona fide science fiction stars in actors like Richard Carlson, Richard Denning, Kenneth Tobey, Julie Adams, John Agar and Beverly Garland.

The foulest curse word in the movie business of the 50’s was “television”. Movie theatres were increasingly forced to compete with entertainment brought straight to the living rooms of middle class homes, and did so through different gimmicks such as colour, widescreen formats and, of course, 3D. The short-lived 3D craze, lasting approximately between 1952 and 1954 was one popular with studios producing SF movies, Universal in particular. However, because of the fickle technology that projectionists were required to master, often 3D screenings were slightly out of sync, especially in smaller theatres, which ruined the experience for many audiences. Partly because of this, the fad died out quickly.

Studios also tried to lure people to the cinemas with spectacle movies, like The Robe, The Ten Commandments and Ben-hur, often costing several million dollars to produce. Few science fiction films received such budgets. One notable exception was Walt Disney’s live-action spectacle 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, starring Kirk Douglas and Peter Lorre, which with its $5 million budget was one of the most expensive films in history. The War of the Worlds, When Worlds Collide, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Them!, Conquest of Space, Forbidden Planet and This Island Earth were among the Sf movies of the 50’s which received substantial studio backing, but most of them didn’t have much more money at their disposal than around $1 million. Many films that are considered classics today were made for no more than $200,000 or $300,000. From the beginning, major studios were sceptical towards throwing money at science fiction, and after the costly semi-flop of Universal’s This Island Earth, SF was strictly relegated to B-movie status. With the exception of Kirk Douglas, no “real” movie stars appeared in science fiction fare. Many actors who are now remembered only for their involvement in low-budget SF and horror movies looked down upon the films they participated in. Only to discover later in life that as opposed to many of their colleagues, who appeared in films that were considered “quality” melodramas and comedies at the time and are now completely forgotten, they were still fondly remembered by genre fans decades later.

Fans of literary science fiction weren’t all happy about the genre’s newfound popularity on the big screen. Genre magazines carried numerous articles insisting that the new wave of UFO’s, little green men and bug monsters were doing more harm than good to the reputation of the genre, as profit-hungry studios dumbed down its concepts and slapped on clichéd Hollywood tropes in order to err on the side of safety. Some argued that serious science fictions concepts simply can’t be properly adapted for the screen, as the writing doesn’t follow film logic. Others argued that the technology for portraying the wonders of the future or outer space didn’t yet exist within the movies. As a rule, people who wrote science fiction scripts didn’t have much experience with either reading or writing science fiction – there were exceptions, of course. Rather, SF authors were more generally employed by anthology shows on television, like Lights Out or Tales of Tomorrow, precursors of The Twilight Zone, that presented genre stories aimed at an adult audience.

Mugglers love to poke fun at the often clumsy and clunky, sometimes endearingly naive SF movies of the 50’s. And it’s true that there is a lot to snigger at, from the dated gender roles to hubcap flying saucers dangling from wires, ridiculous rubber monsters and extremely silly concepts. However, much of it is still wonderfully fun and entertaining if you don’t put your expectations too high. And then there are true masterpieces of cinema among the giant spiders, alien amazons and robot monsters. More than anything, the 50’s SF movies shaped our understanding of the genre, for good and bad, and looking back at the films today, they provide a unique window into an extremely fascinating period in time. The beautiful thing about science fiction is that in removing the stories from our humdrum reality, the genre often says volumes about the times in which the stories were created – mostly wholly involuntarily.

Janne Wass