An alien tests humanity by giving five people the means of killing all humans on Earth. The intriguing premise of Columbia’s 1957 film quickly regresses into red scare histrionics. 4/10

The 27th Day. 1957, USA. Directed by William Asher. Written by John Mantley & Robert Fresco. Starring: Gene Barry, Valerie French, George Voskovec, Azemat Janti, Arnold Moss, Stefan Schnabel, Maria Tsien. Produced by Helen Ainsworth. IMDb: 6.2/10. Letterboxd: 3.1/5 Rotten Tomatoes: 4.4/10. Metacritic: N/A.

On a perfectly ordinary day, five seemingly random people are abducted by aliens. These are: US newspaper reporter Jonathan Clark (Gene Barry), British beauty Eve Wingate (Valerie French), German scientist Klaus Bechner (George Voskocek), Soviet soldier Ivan Godofsky (Azemat Janti) and Chinese villager Su Tan (Maria Tsien). They are taken to a UFO, where an alien (Arnold Moss) gives them each a pillbox containing three capsules. Each set has the power to wipe out all humans on one continent. The five humans are told that the box can only be opened by the individual it has been gifted to, telepathically, but the capsules can be used by anyone (conveniently, they destroy life at any coordinates you speak to them). If none of the weapons are used within 27 days, they will be rendered harmless. Also, if any of the humans who were gifted the boxes should die, their weapons will also be nullified. The humans are then sent back to where they were taken from, with a giant moral dilemma on their hands.

That’s the setup to Columbia’s 1957 movie The 27th Day, largely considered as one of the more intelligent and sudbued science fiction films of the latter half of the 50’s. It was directed by William Asher, from a script by John Mantley and Robert Fresco, based on Mantley’s novel from the previous year, and released as the bottom bill to the Ray Harryhausen movie 20 Million Miles to Earth (review).

The aliens’ intentions are somewhat convoluted, but in short: their sun in going supernova in 35 days, and and they need a new home. They do not want to invade earth, but rather gives humans the opportunity to wipe out themselves (only humans will be harmed by the capsules), so they can take over Earth. If humans are able to refrain from using the capsules for 27 days, the aliens will accept their fate and perish.

The plot then follows the five individuals given the capsules — or four at least, since the Chinese woman commits suicide after returning to her home. The beginning of the film sees her husband killed by soldiers. Eve throws her capsules into the ocean and flies over to Los Angeles to meet up with John. John, on his part, goes into hiding with Eve, hoping to ride out the 27 days in secrecy. Bechner also travels to America, where he is holding a lecture. Ivan tries to keep the capsules secret from his superiors, fearing they will use them to start a devastating war.

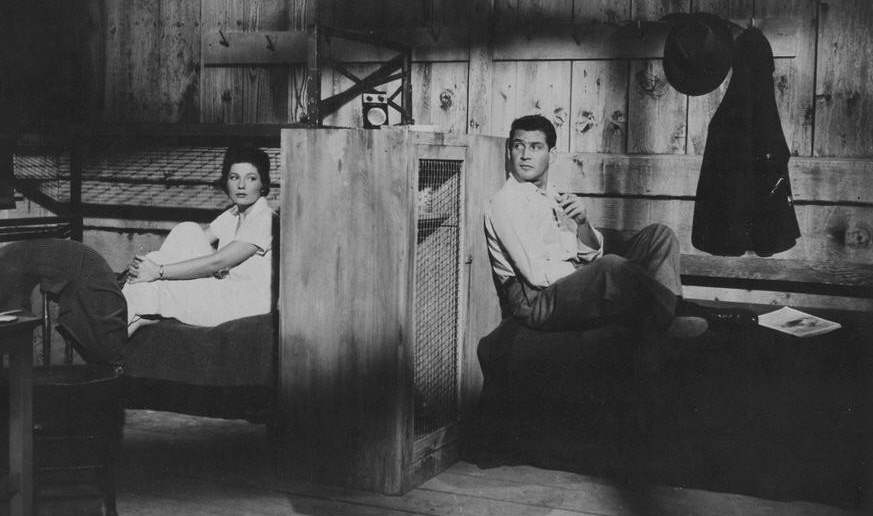

However, the alien throws an additional spanner in the works with a worldwide broadcast where he outs the five recipients of the capsules, throwing the world into panic. Bechner, absent-minded after watching the broadcast, walks in front of a car and is hospitalised, while Ivan is captured by the Soviet military brass, but refuses to divulge the secret of the capsules, even under torture. John and Eve hide out on a small room at an off-season race horse track, while all of America searches for them.

Ivan finally breaks and opens the box, giving “the Soviet General”, as he is credited (Stefan Schnabel), the opportunity to blackmail the US, issuing an ultimatum that USA must withdraw all its foreign troops to America, or else…. The Americans comply, at least seemingly, but at the same time, John and Bechner decide to reveal the secrets of the boxes to the US government. They decide to test if the alien was telling the truth by “detonating” one of the capsules in the Pacific Ocean, and the brave scientist Dr. Neuhaus, a German immigrant (Friedrich von Lebedur), volunteers as the test subject. Eve, John and Bechner board a marine ship commanded by an unnamed Admiral (Paul Birch) which anchors just off the danger zone to test the capsule — and it works.

Meanwhile, the pesky Commies are, naturally, not thinking about humanity, but about world domination and getting rid of all Americans. Placing the epicentre of their three capsules over strategical spots in North America, their plan is to wipe out every single American just before the 27-day limit is over. The Americans anticipate this, but Bechner has an idea and locks himself in a room, studying the markings on the three American capsules, which he determines are mathematical symbols. Just before the stroke of 27 days, he locks the others out and starts giving coordinates to the capsules. Meanwhile, in Russia, Ivan delays the Soviet General’s attack by throwing the capsules off a balcony, giving Bechner just enough time to read out the coordinates over the Kreml. Just as the Soviet General is reaching for his capsules, he dies. Bechner explains that he remembered that the alien didn’t say that the ones holding the capsules have the power over life or death on Earth, but life and death. After solving the mathematical puzzle, Bechner reprogrammed the capsules so that they would not kill indiscriminately, but only those people who were “enemies of peace and freedom on Earth”. Which in this context, of course, means the Commies. Having now wiped out all communists, Earth unites in peace and harmony, and the UN, in a gesture of its new solidarity, invites the aliens to take refuge from their dying planet on Earth.

Background & Analysis

The 27th Day is a somewhat obscure film, but well known to aficionados of 50’s SF movies, as one of the more original ones. As opposed to much of the SF that was being churned out in the latter half of the 50’s, this is an idea film, rather than a monster cash grab. I have not found much information on the hows and whys of Columbia’s decision to adapt John Mantley’s 1956 novel with the same name as the bottom-bill to 20 Million Miles to Earth, a King Kong-inspired monster movie. In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, script co-writer Robert Fresco said that he was handed the assignment to adapt Mantley’s novel from producers Helen Ainsworth and Lewis Rachmill.

According to Fresco, a seasoned and sought-after writer, he stuck closely to Mantley’s book, “amplifying” certain aspects. However, Fresco admits, despite an interesting premise, the whole story “was full of holes and there wasn’t a lot you could do”. Eventually, the author John Mantley himself was called in to rewrite the script, and according to Fresco, ripped up most of the changes that Fresco had done. I haven’t read the book, but according to several sources, it is, unsurprisingly, a very faithful adaptation, even if Bud Webster at the magazine Fantasy & Science Fiction writes that the film is “even more blatantly anti-Communist than the book, which is saying something”. Despite doing the groundwork on the script, Fresco didn’t receive a script credit. He tells Tom Weaver that he simply didn’t think it was worth fight for a screen credit on this movie.

Mantley wasn’t primarily an author, but started his career as a stage and radio actor in the 40’s, did some film and TV work in the early 50’s, and started writing screen- and teleplays, as well as producing, in the mid-50’s, often uncredited to begin with. The 27th Day was developed during his time in WWII, and published in 1956, and as far as I can tell, it was Mantley’s only novel.

Director William Asher was, at the time, primarily a TV director, having directed over 100 episodes of the I Love Lucy show between 1952 and 1957. And while the premise of The 27th Day holds interesting opportunities for atmosphere and paranoia, Asher doesn’t do much with it, filming in a flat and matter-of-fact manner. There’s a few interesting shots, such as Jonathan and Eve sitting alone at the huge, abandoned race track, but these are only moments punctuating an otherwise bland directorial style.

The film’s biggest asset, and also its biggest flaw, is the script. It’s easy to be taken in by The 27th Day. The premise is very interesting, and holds great potential. Even though the idea for the movie might have come about in the trenches of WWII, it is clearly inspired by The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review). Like Klaatu, “the Alien”, as he calls himself, comes to test the morality of human civilisation, giving the people of Earth the choice between annihilation and peace. Like the former movie, The 27th Day wants to point a finger at humanity’s propensity for war, rather than cooperation. By giving five people from different countries the means for absolute destruction, the film sets up a uniquely interesting premise. And then fails to do anything with it.

Wouldn’t it have been interesting if the five people could have been placed in a room banging their prejudice against each other? A bit like 12 Angry Men, but with humanity at stake? Learning, developing, finding understanding. But no, instead the Chinese woman is promptly taken out of the picture, the Russian shipped off to his native country and the English woman takes herself out of the equation by throwing the capsules into the sea (actually the most sensible moment in the entire movie). For the rest of the film, Eve is only along for the ride as a lame romantic interest. The blatant US-centrism of the film is staggering. The Asian angle is killed off from the start, and Africa, Oceania and South America are treated as if they didn’t exist. Apart from the Chinese, not a single person of colour receives a box. The cultural illiteracy of this film is so staggering that it has the Chinese woman kill herself through seppuku. Then the two Europeans ditch their continent entirely, both travelling to America, as if the US was the undisputed centre of the world, when their own countries, friends and families are threatened by annihilation. Come to think of it, don’t any of the protagonists have any family members to contact?

For half of the film, Jonathan and Eve are holed up in a shack by the race track, giving them ample time to go into deep conversations. Instead, Mantley simply has them playing house, an exercise that is completely redundant for the movie. What pseudo-philosophical exchanges they do have are banal.

Instead of delving deeper into the more subtle themes teased in the first half of the movie, the second part quickly descends into the sort of red-scare histrionics that were actually becoming rather passé in the late 50’s. The film loses all sense of credibility when the Soviet General states as the intent of the Soviet Union to literally wipe out every single American on the planet, in order to give the Communists world domination. Even by the standards of anti-communist propaganda movies in the 50’s, this is absurd.

But it is the laughable deus-ex-machina ending that ultimately trips The 27th Day. Dr. Bechner is able to decipher that he can reprogram the capsules to kill only the “enemies of peace and freedom” on Earth. Even if we buy that the aliens have been able to program a weapon that can look into the souls of every human on Earth, the definition “enemy of peace and freedom” is a very fuzzy definition, even in Earth terms, depending very much on who it is that has the power to interpret “peace and freedom” and how and why one is an enemy of these. And in this case, the definition has been pre-programmed by an alien. I know I would be rather hesitant to pull the trigger on such a gun. As it turns out, “enemy of peace and freedom” literally seems to mean “communist”, making it look as if the aliens are actually conservative Americans in disguise. The idea that if the world just got rid of all its communists, we would magically come together in peace and harmony is, of course, beyond idiotic. Not least looking at how many wars and atrocities that have been carried out in the name of European and American values and “civilisation” (or imperialism, if you like).

Furthermore, the moral assumption is also more than a little muddled. By Bechner’s actions, humanity proves itself as a high-standing and moral civilisation, and is invited into the A-league of “30,000 worlds”. While the initial assumption the viewer makes is that the film would promote a live-and-let-live attitude, in fact it promotes a kill-the-Commies attitude. By rough calculation, there would have been around a billion communists or socialists in the world in 1957. The “moral high ground” in this case then seems to be a genocide at a magnitude that would make the Nazi war crimes a drop in the ocean by comparison. Not to mention that many European countries were actually governed by socialists in the late 50’s. I don’t think Europe would have blissfully welcomed this new era of “peace and freedom” after their democratically elected governments, not to speak of friends and family, had been murdered on the whim of a misguided scientist locked in the cabin of a US naval ship. This must be one of the most absurd endings of a movie I have ever witnessed. Not to mention, a very damp squib.

All that said, the premise of the The 27th Day is original enough to hold interest, almost throughout the film, and if you ignore the glaring plotholes and the warped logic, the script holds together. As stated, much of what is being said is rather banal, but the dialogue is still a slight cut above most B-movies of the era. Because the film is so short, just a little above 70 minutes, it doesn’t have time to get boring. But on the other hand, the short running time also means that we just jump straight into the action, and don’t get any time to get to know the characters. These are characters that don’t seem to exist outside of the plot. Both women are given male companions, one if whom dies in the film’s first scene, and another one who never gets another mention after we first meet him in the introduction. The three male protagonists don’t seem to have a life outside of their work. All five protagonists are almost completely devoid of any personality, which means that we don’t really care what happens to them. This makes the movie very much an intellectual exercise, and as we have noted, there is not much intellect in the exercise.

The acting is fine, considering the material. That Gene Barry was capable of better things, he proved in The War of the Worlds (1953, review). Here, his awkwardly written role puts restraints on him. Valerie French doesn’t get much to do other than inexplicably fall in love with Barry and look worried. George Voskovec does his best imitation of the timid, friendly Sam Jaffe in The Day the Earth Stood Still, and brings at least some warmth and sympathy to the proceedings, and Azemat Janti, in the largest role of his short career, is actually quite good as the tortured Russian soldier. British character actor Arnold Moss does much to sell the premise of the film as the alien, and Stefan Schnabel as the Soviet General does a role that he could do in his sleep by this time. Maria Tsien as the Chinese woman gets neither a line nor a credit.

For completists, this is a fun watch as something a bit out of the ordinary, as long as you don’t mind pulling your hair at the idiocies of the script.

Reception & Legacy

The 27th Day premiered in July, 1957, and often played as a bottom bill to Columbia’s 20 Million Miles to Earth. The film received mixed reviews in the trade papers. Harrison’s Reports called it “a better-than-average science-fiction program melodrama”, praising an interesting story that works up “considerable tension”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor also called it “better than most” science fiction films, noting an “extremely interesting premise”, which “holds interest until the end when the story gets a bit complicated and confusing even for the science fiction devotees”. The Film Bulletin wasn’t quite as positive, noting the movie was “right up there in the celluloid stratosphere of hokum, hodge-podge, and the desperate, though earthy, attempt to make a fast buck”. And The Motion Picture Daily opined that The 27th Day “packs no real punch because it is weighed down by a plethora of dialogue and an unnecessary love story. It starts off well enough but the noticeable lack of thrills or excitement despite an inherently suspenseful idea, dissipates the basic attributes.”

In his 1970 book Science Fiction in the Cinema, John Baxter gives credit to the film’s original idea, “simple directness of execution” and its optimistic view of mankind, but like many others he feels let down by the final plot twist.

Today the film seems to be better liked by the general audience than by the critics. It has a very decent 6.2/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on almost 2,000 votes, and a better-than-average 3.1/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on 500 votes. However, it only has a 4.4/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes.

In his book Keep Watching the Skies, film historian Bill Warren seems to have difficulties making up his mind about The 27th Day. Warren bemoans the naive and simplistic ending, the plodding pace and the preposterous political ideas at the climax, but still applauds the fact that at least the film “is about something”, as opposed most science fiction films at the time, and calls the proceedings up until the bewildering ending “surprisingly intelligent and interesting”.

As stated, there are wildly conflicting views on this film. Fred Azerdo at ImaginAtlas waxes poetical about the “beauty of the film’s understated allegorical storytelling”, which he feels makes The 27th Day a worthy companion to classics like The Day the Earth Stood Still and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. On the other hand, there’s David Cairns at Mubi, who in his column calls it “an ideas-driven sci-fi thriller conceived and executed by idiots”.

My go-to online critics aren’t slow to point out the film’s propagandistic core. Even those who like the film, like Richard Scheib at Moria, who gives it a 3/5 star rating, notes the film’s purpose as a propaganda vehicle. However Scheib does applaud the way in which the film “plays out the moral arguments for and against the use of the devices and the tensions that escalate on an international level”. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings finds the first half of the film intriguing, but feels that it “eventually settles into a much more conventional cold war good-guys-vs-bad-guys scenario that I found far less interesting”. Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV calls The 27th Day “as blatant a piece of anti-Communist propaganda as the 50s SF cycle was ever going to produce […] representing the USA (and its allies in Europe) as the only ones worthy of surviving the holocaust”. Lyons further says that even overlooking the propaganda, The 27th Day “lacks the allegory of [The Day the Earth Stood Still] and is certainly a lot less subtle in either the crudity of its polemic or simply its method of delivery. While Wise’s direction had been sprightly and engaging, Asher’s is merely plodding and leaden, lacking in atmosphere.” DVD Savant Glenn Erickson opines that “On its surface The 27th Day offers a nifty moral dilemma […] But The 27th Day gives up its amateur allegory status to come right out with a rather embarrassingly bone-headed anti-Commie statement. The movie’s eventual message is not ‘we must live in peace’ but ‘the only good Red is a dead Red’.”

Cast & Crew

Director William Asher was not only a seasoned professional, but one of the pioneers of American TV. While he began his career as a movie director in 1948, he almost immediately gravitated towards television, and got his first directorial TV credit in 1952. That same year he became the primary director of the groundbreaking I Love Lucy show, and directed the lion’s share of its 181 episodes that aired between 1951 and 1957. In 1964 he then became the primary director on Bewitched (1964-1972, and from 1967 on he also produced the series.

Movie-wise, Asher’s achievements are also biggest on the comedy side. His film fame rests almost entirely on the five “beach party” movies he directed for American International Pictures between 1963 and 1965, perhaps inadvertedly creating a whole new genre. When producer Sam Arkoff paired Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello in the very first movie in AIP’s series, Beach Party, in 1963, the directorial job went to William Asher. After the tremendous success, Asher was called back to direct the next two films in the series as well, Muscle Beach Party (1964) and Bikini Beach (1964). He made two more beach films for AIP, Beach Blanket Bingo (1965) and How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1965). In the latter films he was also involved as screenwriter.

Throghout Asher’s career, however, TV provided his bread and butter, although he occasionally returned to the big screen. He kept working with various productions, as producer, director and/or writer up until 1990, when he retired. Bewitched had him Emmy nominated twice as a producer and twice as a director. He won for best direction on a comedy series with Bewitched in 1966. The 27th Day was his only SF movie.

Screenwriter John Mantley was a bit of a jack-of-all-trades in showbiz. A Canadian, Mantley was born into a performing family, and spent much of his youth on the road with a travelling circus, where he mainly worked behind the stage or as a vendor. His passion, though, was acting and he started a drama club in high school, and went on to study at the Pasadena Playhouse in California after serving in WWII. Much of his early career was spent on stage both in Canada as in the US, on and off Broadway. In the earlty 50’s, Mantley alternated between stage and radio, more often as a producer than as an actor, and eventually also became involved in both writing and producing for local TV stations in New York, and later Los Angeles. In the mid-60’s he was a full-fledged TV producer, and rose to fame and success as the producer of the extraordinarily successful western show Gunsmoke between 1965 and 1975.

The film was produced by Romson Pictures, for Columbia. Romson was movie and TV star Guy Madison’s production company, in which he partnered with his agent, Helen Ainsworth. It was Ainsworth who worked as the credited producer of The 27th Day. Ainsworth was one of the many stage actresses called into movie service with the advent of sound in the late 20’s. However she only appeared in around a dozen films, before starting work as an agent. She was instrumental in launching the careers of Hollywood figures such as Marilyn Monroe, Carol Channing, Guy Madison and Howard Keel. She also produced around half a dozen films for her and Madison’s company before her untimely death at only 59 in 1961. Robert Fresco describes Ainsworth as a “very large, very pleasant woman who had connections and money … She had impeccable manners, she had a beautiful education, and she was very nice to me”. However, the de facto producer of the film was Lewis Rachmil, who, according to Fresco was “not a very nice man”, as Ainsworth started flying off to Italy in order to produce spaghetti films with Madison.

Gene Barry (born Eugene Klass, he took his moniker from actor John Barrymore) was a ”song and dance man” from the New York stage who drew up to Hollywood with his family after ending a tour in the South, and managed to secure a contract with Paramount on a whim in 1951, just three days after arriving in Los Angeles. According to an obit in The Telegraph, the news came as such a shock to his wife that she fainted and fell into a pool. After a few TV guest spots, he secured his first lead in The Atomic City, and was then shoved directly into The War of the Worlds (1953), with a salary of 1 000 dollars a week, or between 9 000 and 13 000 dollars today, depending on how you count. In comparison, lead actress Ann Robinson made 125 dollars a week.

Barry appeared in five more Paramount films, and some low-budget indie features like the sci-fi movie The 27th Day (1957), where he again played the lead, and headed down a successful TV career in the late fifties, which lasted all the way into the 21st century. In 1955 he appeared on a couple of episodes of Science Fiction Theatre, and had a role in a episode of the revamped The Twilight Zone on 1985. He also played one of the three rotating leads in the TV show The Name of the Game, which featured the occasional sci-fi episode. However, he shot to TV stardom in the title role of his first big TV series Bat Masterson (1958-1961), continued by Burke’s Law (1963-1966), he further had the lead in The Adventurer (1972-1973), but after that he mainly appeared as a guest star, although Burke’s Law was revived for one season in 1994. He more or less retired after this. In an interview with my favourite film historian Tom Weaver, he claims that although he had a very successful TV career, he had some regrets about accepting the role as Bat Masterson, since it, in his opinion, killed his movie career. In the book Earth vs. the Sci-fi Filmmakers: 20 Interviews Barry says: ”I had a fine television carer – but I had a lousy movie career [laughs]! It’s the truth. In those days, it was a negative stamp, making the move into TV.”

On the other hand, the films he played in after The War of the Worlds weren’t exactly stellar, and he often got pushed down to fourth or fifth billing, so in all honesty TV probably saved his career. Barry also did a number of stage performances and toured the world as a singer, and even released a crooner album. His performance in La Cage aux Folles on Broadway in 1983 was a smash hit and earned him a Tony nomination. Barry often played wealthy, debonair characters, and the roles were mirrored in real life, where he would always dress in an impeccable suit and drive around town in a Rolls-Royce. Barry won a Golden Globe for his work on Burke’s Law, a Golden Boot for his work in westerns and has a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his stage work.

Weaver interviewed Barry just before the Steven Spielberg remake of War of the Worlds (2005) went into production, and asked him if he would be interested in a cameo if approached. Barry responded: ”Of course I would take it. It would be thrilling.” Well waddayaknow? Along with co-star Ann Robinson, Barry had a cameo in the movie, where the pair played the mother and father of Tom Cruise’s on-screen wife, showing up in the final scene of the movie. Barry passed away in 2009.

English actress Valerie French was born in London in 1928 and had a promising career on stage in the early 50’s, and appeared in a few British films before heading to Hollywood in 1955. In typical Hollywood fashion, she was touted as having been chosen as “Miss Galaxy” in the UK, a pageant that seems to be rememberd solely because of French’s win. Her Hollywood career didn’t prove exactly stellar. She was signed to Columbia, and immediately got a co-lead in the western Jubal (1956), opposite Glenn Ford, Ernest Borgnine and Rod Steiger, but that remained her best remembered film. One interesting movie she appeared in as a featured player was Garment Jungle (1957), the story of the struggle of workers at a NY garmet factory trying to get unionized. After the SF movie The 27th Day (1957) and a few B-westerns, she went freelance, but primarily found work in TV. French remained in the US, however, and in 1960 returned to the stage, and became a regular face on Broadway. In 1969 she caused a minor sensation by appearing nude on stage. She spodadically took part in TV and film productions through the 60’s and 70’s.

George Voskovec was born Jiří Voskovec was born 1905 in current Czech Republic, and worked as an actor, writer and director on the Czech stage, primarily in the Osvobozené divadlo (Liberated Theater), and often alongside actor and playwright Jan Verich. With the rise of fascism, the group was banned, and Voskovec fled to the US. He made a brief return in to Czechoslovakia in 1948, but left for France when the Nazis took power. In 1950, he returned to the US. After having fled one authoritarian regime, he was paradoxically imprisoned for eleven months at Ellis Island upon his return to the US, because of alleged Communist sympathies, making his performance of the commie-slayer Dr. Bechner in The 27th Day (1957) rather ironic. Voskovec is best known as the sympathetic immigrant juror N:o 11 in 12 Angry Men (1957). Other noteable appearences were in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and The Boston Strangler (1968). Voskovec was steadily employed as a character actor in Hollywood throughout the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s.

Arnold Moss appears briefly, but memorably in The 27th Day (1957) as the regal alien. Because of his Shakespearean dictation and aristocratic bearing, Moss is regularly mistaken for British, but he was, in fact, born in Brooklyn. Born in 1910, he received an extensive education and was set for a teaching profession before he decided to pursue a career in acting, and eventually started his own Shakespearean company. On Broadway he played Prospero in The Tempest in 1945, a show which ran for over 120 nights, setting a Broadway record for the play. His mellifluous bass voice quickly led to a career in radio, where he debuted in 1931. He made his film debut in 1946, and would often play suave villains. He was also a narrator for several symphony orchestras, and appeared in dozens of TV shows, including Dimension X (1955), Lights Out (1950-1951), Tales of Tomorrow (1951-1952), Star Trek (1966) and The Time Tunnel (1967). As if all this wasn’t enough, he also created the New York Times Sunday crossword.

Speaking of The Tempest, this was the play in which Stefan Schnabel made his debut at The Old Vic repertory theatre in London in 1933. Schnabel wasn’t seen though, but played a wind effect off-stage. Born in 1912, as a child Schnabel entertained foreign kids in Berlin who attended his parents’ music classes. He was quickly tasked with learning British and American children English, which led to him soon becoming fluent in English. This served him well when he fled Nazism to London in 1933, and pursued an acting career. He made thje trip to New York in 1937, where he started to work in radio and soon became a part of Orson Welles‘ Mercury Theatre. All in all, he appeared on over 5,000 radio shows in his career, when he was not appearing on Broadway, playing Nazis and Communists in films, or busy with his 17-year run as Dr. Jackson on the soap opera The Guiding Light in the 70’s and 80’s.

Stocky, barrel-chested lead actor Paul Birch was an original member of the Pasadena Playhouse stock, and worked as an acting teacher. On the side of his stage career he appeared in 39 films and was a popular guest star on over 100 TV shows between the mid-forties and late sixties. His first brush with science fiction came in 1953, when he was among the first to be disintegrated in George Pal’s The War of the Worlds (review). In the mid-fifties he became part of Roger Corman’s stock company. Corman gave him leading roles in all the three SF movies he appeared in. He played the family father fighting the alien in The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955, review), the stern former military man who runs the safehouse in Day the World Ended (1955, review), and the mysterious fedora-wearing vampire from outer space in Not of This Earth (1957, review). Other SF films he appeared in was Columbia’s The 27th Day (1957), where he had a supporting role as an Admiral, and Allied Artist’s Zsa Zsa Gabor vehicle Queen of Outer Space (1958, review), in which he played one of the astronauts landing on the all-female planet of Venus.

Tall, gaunt aristocrat Friedrich von Lebedur was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian cavalry in WWI, after which he spent the following two decades travelling the globe. He finally settled in the US in 1939, where he was able to use his expertise with horses to establish himself as a sought-after horse trainer in Hollywood. In 1945 he started getting small roles in movies, and soon befriended John Huston, who cast him in prominent roles in his films. He could be glimpsed in such A-films as The Great Sinner (1949), Moulin Rouge (1952) and Alexander the Great (1956). In 1956 he also appeared in what would become his most famous film, that of master harpooner Queeqek in Huston’s Moby Dick (1956). Surely, Lebedur must have asked himself what he did, the year after this triumph, appearing in The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957, review), Voodoo Island (1957) and The 27th Day (1957). Lebedur eventually returned to Europe in the early 60’s, where he continued to act in primarily German movies. But he also appeared in occasional Hollywood movies filmed in the continent, such as Huston’s Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), William Friedkin’s Sorcerer (1977) and Terence Young’s Bloodline (1979). Most famously, perhaps, as the German leader in the SF movie Slaughterhouse-Five (1972).

As the Chinese woman in The 27th Day we see Maria Tsien, born Maria Lim Bi Yao in 1925 in the Philippines to Chinese parents. She studied at St. John’s University in Shanghai and later at Columbia University in New York. Eventually, she made her way to Hollywood, where she started appearing in movies and TV in the mid-50’s, often in uncredited bit-parts calling for an Asian actress. She is probably best known for playing the royal wife opposite Yul Brunner in The King and I (1956), albeit once again uncredited. When she was credited, it was as Marie Tsien. After marrying film publicist Booker McClay in 1960, she was billed either as Maria McClay, Marie Tsien McClay or Maria Tsien McClay. All in all, she appeared in around a dozen films and as many TV shows. She retired from acting in 1964. According to a Los Angeles Times 2020 obit, the McClays “enjoyed watching films and traveling around the world. Maria was known for her vivacious personality. She was a generous benefactor of many charitable organizations”.

Janne Wass

The 27th Day. 1957, USA. Directed by William Asher. Written by John Mantley & Robert Fresco. Starring: Gene Barry, Valerie French, George Voskovec, Azemat Janti Arnold Moss, Stefan Schnabel, Maria Tsien, Friedrich von Lebedur, Paul Birch, Ralph Clanton, Paul Frees. Music: Mischa Bakaleinikoff. Cinematography: Henry Freulich. Editing: Jerome Thoms. Art direction: Ross Bellah. Sound: Ferrol Redd. Produced by Helen Ainsworth for Romson Productions & Columbia.

Leave a comment