An everlasting classic and a pioneering work, George Pal’s 1953 alien invasion epic set the standard for visuals in SF movies. Unfortunately, in removing itself from H.G. Wells’ themes, the script loses both its poignancy and its dramatic functionality. 7/10

The War of the Worlds. 1953, USA. Directed by Byron Haskin. Written by Barré Lyndon. Based on novel by H.G. Wells. Starring: Gene Barry, Ann Robinson, Les Tremayne, Lewis Martin, Paul Frees. Produced by George Pal, Frank Freeman Jr. & Cecil B. DeMille. IMDb: 7.1/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 89/100. Metacritic: 78/100.

There are a few films that stand towering over science fiction like giants in respect to their influence on the genre. George Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902, review), Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927, review), and Woman in the Moon (1929, review), James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931, review), Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984), the Wachowksi’s The Matrix (1999), Aflonso Cuaron’s Children of Men (2004), Marvel’s Iron Man and and Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014) are among these. They are not always the best in their genre and some of them are hampered by by serious problems. They are not always first in their field with their ideas, but execute them in ways that make them milestones to which you can pin flags and draw a line: this was science fiction film history before this-and-this film, and this is what it looks like afterwards. George Pal’s The War of the Worlds is one of these films, it is the Magnum Opus of a filmmaker that wasn’t always savvy to what made a good sci-fi script, but without question one of the great visionaries of movie history.

Based very loosely on H.G. Wells’ novel with the same name from 1897, the film takes its time to get going, starting with a long narration by Paul Frees, who guides us through military stock footage in a faux news report, giving us a warning about future wars and new super-weapons. Then British Thespian Cedric Hardwicke gives us the exposition in a second narration with stunning Technicolor renderings of our solar system: Mars is dying and the Martians look to all the planets in the solar system for a new home, and the only one that fits is Earth.

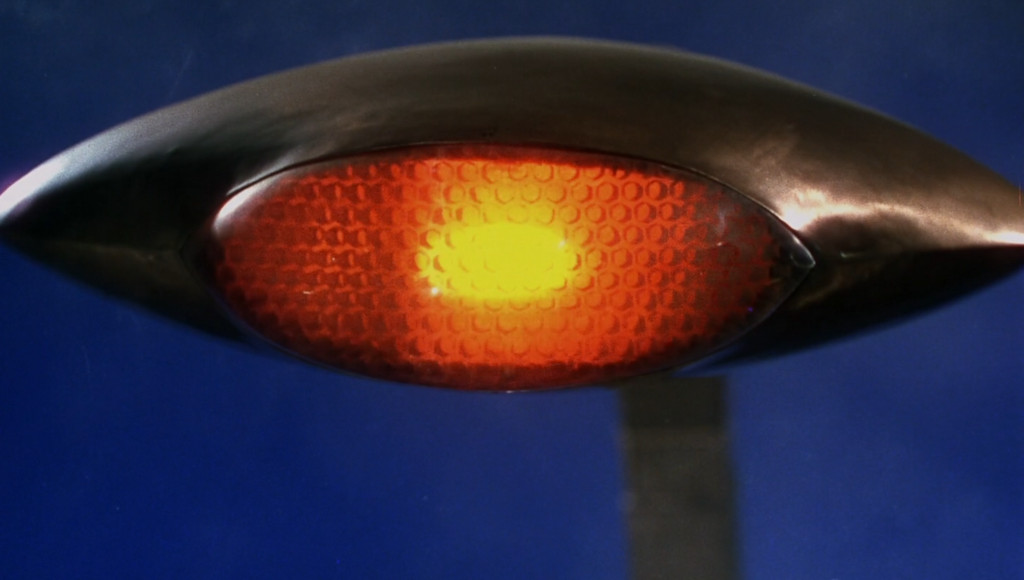

The film proper begins almost in medias res, with strange meteors crashing near a small town outside of Los Angeles, moving the story away from Wells’ London and into the 1950s. The handsome Dr. Clayton Forrester (Gene Barry), who happens to be in the area for a fishing trip with his colleagues (Roberth Corthwaite and Sandro Giglio) is called in to investigate the burning hot, strange-looking whoppers. At the site of the crash he meets the lovely university teacher Sylvia (Ann Robinson) and her uncle Pastor Matthew (Lewis Martin), among the hustle and bustle of curious onlookers, firemen, US Marshals and radio reporters. Clayton notes that the large “meteorite” is radioactive. When evening comes, the townsfolk decide to let the “meteorite” cool until morning, and head down to the town hall for a bout of square dancing, where Clayton and Sylvia have eyes only for each other. Three nitwits, including SF notability William Phipps, are left to guard the “meteorite”. While the merriment is commencing downtown, the three stooges observe a hatch unscrewing in the “meteorite”, and a cobra-like “neck” with a pulsating electronic “eye” at its “head” emerging from the manhole. They approach with white flags in order to greet the stranger, but are ruthlessly burned to ash by a powerful heat ray from the “eye”. At that very moment, all lights in town go out, and all clocks stop because of a powerful magnetic wave.

Now commences the second act of the movie, as Clayton, Sylvia, the pastor and the townsfolk return to the crash site, and realise the true nature of the fallen object — it is an alien invader. Among those gathered is also radio reporter Paul Frees, who keeps up an ongoing commentary and reveals exposition throughout the movie, revealing Barré Lyndon’s difficulties with turning Wells’ intellectually challenging novel into dynamic moving pictures. In case we don’t forget that we are watching BIG MOMENTS, Frees regularly returns to us with BIG STATEMENTS like “The whole world is waiting, for this will decide the fate of civilization, all Humanity, whether we live or die, may depend on what happens here”.

The army rolls in, led by Maj. Gen. Mann (Les Tremayne), and witness three strange, triangular war machines (the “heads” of which have been visible earlier), seemingly floating in air (but Clayton explains they are walking on three “invisible legs” of magnetism, meaning that the film — technically — keeps the famous tripods from Wells’ book). General Mann reports that similar machines have landed all over the world, and are now spreading death and destruction. But before the army can fire their weapons, the brave, kind pastor whom we have grown to like decides to approach the Martians in a last effort to make contact — believing that as intelligent beings they would have no reason to be inherently hostile. Knowingly walking into possible death, the heroic servant of God strides forth, Bible in hand, reciting “Even though I walk though the valley of the shadow of death …”. And is promptly barbecued by a heat ray. The army unleashes hell — but their grenades are useless against the Martians’ magnetic force shields. The Martian war machines tear through the army’s lines, and Clayton and Sylvia escape in an airplane, crash land in the wilderness, where act three starts.

After a day and night running and hiding from the war machines, Clay and Sylvia find a deserted house where Sylvia makes breakfast for Clay, and Clay tells her that she “isn’t going to bawl because she is tough”. But alas, their time playing house is cut short, when a another space ship crash lands square in their kitchen. This leads to the most iconic scene of the film, in which Clayton and Sylvia encounter a tentacled Martian probe and an actual Martian, before fleeing. With a captured piece of alien technology and a rag covered in Martian blood, the two head to San Fransisco to Clayton’s university to get them analysed.

In act four we meet up with the human resistance in San Fransisco — army brass pushing figurines on a huge table map, Paul Frees making long-winded speeches — on tape, because, “All radio is dead, which means that these tape recordings I’m making are for the sake of future history – If any”. Now comes the moment when the US army brings out its weapon of doom — the atom bomb, “ten times more powerful than anything previously used, it’s the latest thing in nuclear fission”, as the reporter tells his tape recorder. But as the smoke clears, the Martian machines emerge again, not as much as dented. All hope is now lost, unless our team of scientists can figure out what makes Martians tick, with the help of Clay’s and Sylvia’s loot. But alas — all research is lost as the Martians approach and angry mobs take over the streets, attacking the scientist’s trucks as they are about to evacuate. Clayton gets separated from Sylvia, and spends the final moments of the film searching for her in the churches of Frisco — as he remembers that she told him that she once hid in her uncle’s church. Dodging attacking alien war machines, burning buildings and looting mobs, he stumbles through the chaos from church to church, finding in all of them tranquil refuges and hope in a new tomorrow. Finally together, they await the inevitable end, as the unstoppable enemy moves forth, destroying everything in it path. But lo and behold, then comes the famous final twist! Accompanied by the ringing of church bells and a praise to the almighty Lord, who in his wisdom put on the Earth the seed of the Martian’s destructing through the agency of the smallest thing in his Creation!

The War of the Worlds opened to enthusiastic critical acclaim, hauling in 2 million dollars at the box office in USA and Canada. It was hailed by Monthly Film Bulletin as “the best of the postwar American science-fiction films”, and by The Washington Post as “the King Kong of its day”.

British author, social philosopher and socialist H.G. Wells wrote The War of the Worlds during a flurry of literary activity between 1895 and 1902, during which he published most of his best remembered and most influential novels. These years saw the birth of The Invisible Man, The Time Machine, The Island of Dr. Moreau, The War of the Worlds and First Men in the Moon, among others. The War of the Worlds was Wells’ fourth SF novel, and was first published as a magazine serial, as were most novels in the day. It was also his most successful, and the one that brought him out of the shadow of Britain’s at the time most popular SF writer, George Griffith, who had taken the country by storm in 1892 and 1893 with his epic future war stories The Angel of the Revolution and Olga Romanoff. I’ll write a separate article on so-called invasion literature in the future, but for brevity’s sake, let’s at this moment be content with noting that the alien invasion subgenre was a continuation of so-called invasion literature, hugely popular in Britain in particular, between 1871 and 1914. While not the first author to describe an alien invasion, Wells was right there in the vanguard. What made his story so novel was that he placed the invasion smack in the center of a middle-class borough outside London, and describes it through the eyes of a helpless bystander trying to save himself and his family from the onslaught of the Martian war machines.

The written story differs greatly from that which Paramount and George Pal put on screen. One could almost say that little more than the very basic beats remain. Apart from the obvious addition of the Martians, the original The War of the Worlds also differed greatly from most contemporary invasion literature in a number of ways, in part because Wells turned many of the genre’s tropes on their head. In fact, what George Pal, writer Barré Lyndon and director Byron Haskin have done, is that they have actually re-reversed these tropes, making the film more in line with the conservative, nationalist fiction by writers such as George T. Chesney or William Le Queux, than with the original ideas brought forth in Wells’ novel. Most invasion literature was inhabited by morally upright, brave and noble soldiers, fighting (and often finally prevailing) against impossible odds, despite the failings of their government. They succeeded in their task because they were members of the most advanced people in the world, the pinnacle of evolution and culture, most often either French or British, depending on the nationality of the author. Conversely, the enemies were often depicted as sadistic brutes, bloodthirsty and uncultured.

In The War of the Worlds, as written, on the other hand, we see little of the much-touted British exceptionalism. One of the few soldiers the protagonist encounters is deserter who turns up later with a bizarre plan of continuing human civilisation underground. The book mostly deals with frightened people on the run, trying to survive, as news of the battles reach them by hearsay from afar. As opposed to the film, the book does not portray religion in any good light. One of the protagonist’s companions during his flight is a curate, or parish priest, who shows little faith in the goodness of God, but is more interested in saving his own skin, and rambles loudly and desperately about the coming of Armageddon, and his religious outbursts get him detected by the Martians, who kill him, and almost kill the protagonist. The book doesn’t, either, depict two equally matched enemies, such as the Germans and the British, but rather makes the comparison between a European colonial power like Britain and the indigenous people of the colonies, fighting off British warships, rifles and cannons with spears and arrows. At one point in the book the protagonist makes the comparison between the Martian annihilation of humans and the Europeans driving not only the dodo and the buffalo to the brink of extinction, but also whole human races, like the Aboriginal Tasmanians: “The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of 50 years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?”.

Wells turns the looking glass around, showing what a British colonisation might look like from the viewpoint of African, Asian, or indeed Australian natives . He also points out the atrocities committed by European colonists that were carried out without malice, but rather because they were seen more as pest control than as injustices against other human beings. The Martians in the book show no signs of malice or sadism, but simply go about their business of ridding their new fields of pests, using the blood of humans as sustenance — a harrowing picture if the ever was one of the exploitation of the European colonies. And when the end comes for the Martians, it isn’t through the heroic efforts of the Brits, in fact the protagonist himself is about to commit suicide by Martian heat ray when he discovers that the war machine, the tripod, he approaches is lifeless. The killer is the slow, inevitable march of biology, not British exceptionalism or divine intervention (even if George Pal has interpreted it as such).

The story of how Paramount came to make The War of the Worlds in 1953 with George Pal is long and complicated. The studio bought the rights as early as 1925, and planned it as a project for Cecil B. DeMille. But nothing ever came of it, since the studio either didn’t know how to do the special effects convincingly or thought they would be too expensive. It was pitched to Sergei Eisenstein during his short stay in Los Angeles in the early thirties, but he declined. Renewed interest sprung up after Orson Welles made his legendary live radio drama based on the book in 1938. It turned Welles into an overnight star, and renewed the interest in Wells in the US. Welles was naturally approached to direct a movie version of the story, but he wasn’t interested. Alfred Hitchcock approached H.G. Wells about an adaptation, but since Hitchcock was under contract with Warner and Paramount had the rights to the book, this also fell through. Animation master Ray Harryhausen was keen on doing the movie, and even made a short film to show the studio.

Cecil B. DeMille dusted off his old project when science fiction broke into the mainstream in the early fifties, and was so impressed with George Pal’s Destination Moon (1950, review) and When Worlds Collide (1951, review), that he managed to convince the studio brass to attach the Hungarian puppet animator and special effects visionary born as György Pál to the film (see more on Pal in the reviews of the above mentioned movies). The idea had come from Pal himself, as he had stumbled upon the old scripts while doing post-production for When Worlds Collide at Paramount.

Pal signed on as producer for yet another sci-fi epic. He didn’t like any of the numerous scripts that were lying around Paramount, so got Barré Lyndon to write a new one. Lyndon was primarily known as a mystery/horror writer, and had penned the claustrophobic thriller The Lodger (1944) and play that The Man in Halfmoon Street (1945, review) was based on. Pal had been especially impressed with his work on the thriller The House on 92nd Street (1945) and DeMille’s circus epic The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). Despite some initial resistance from the studio, with some help from DeMille, Pal was able to convince Paramount to let him do the film, with some changes to the script.

Thematically the film is – in usual George Pal fashion – all over the place. Naturally, the theme of the piece is clear – it’s those damn commies again, this time invading USA in spaceships. Just like Red Planet Mars (1952, review), The War of the World pushes the notion that the one thing that stood between the world and Soviet Communism was religion – preferably American Christianity, and that God almighty will strike down even the most invincible foe with the ”smallest thing” he put on Earth.

Moving the action from Victorian UK to modern-day US is a logical decision, and partly a budgetary one. Although made on a decent enough budget, The War of the Worlds still didn’t come close to the real big-budget historical pictures of the day. Quo Vadis (1951) had a budget of over 7 million dollars, and in 1956 DeMille would remake his 1923 silent epic The Ten Commandments in sound for a whopping 13 million dollars. Numbers for The War of the Worlds vary with the source, but the film cost somewhere between 1 million and 2 million dollars to make, and reportedly two thirds of this went into the special effects.

Another reason for the change was that all three people at the reins, Pal, Haskin and Lyndon, thought the film should be identifiable to a modern American audience, ”and that’s who we were making the picture for”, Haskin said years later, according to Melvin E. Matthews’ book 1950s Science Fiction Films and 9/11. And I whole-heartedly agree. Wells wrote the book for his readers, Londoners of 1898, to comment on contemporary issues. Paramount made their version in order to comment on the questions of their day. And, regardless of your opinions on the film’s political or moral stance, the question at hand for many Americans at the time was the fear of a war with the Soviet Union. Plus, as Haskin pointed out, ”With all the talk of flying saucers, War of the Worlds had become especially timely”.

I would go as far as to say that The War of the Worlds is a film that should be updated with every adaptation. One of the reasons it has been remade so many times, as films, radio plays, TV series, comic books, video games, even a musical, is that it lends itself so well to adaptation and updating. That said, it is remarkable how few adaptations actually put on screen what Wells wrote, considering that Wells is a very filmatic writer, and The War of the Worlds is one of his most filmatic books. And we’ll get to some of the problems with the script later.

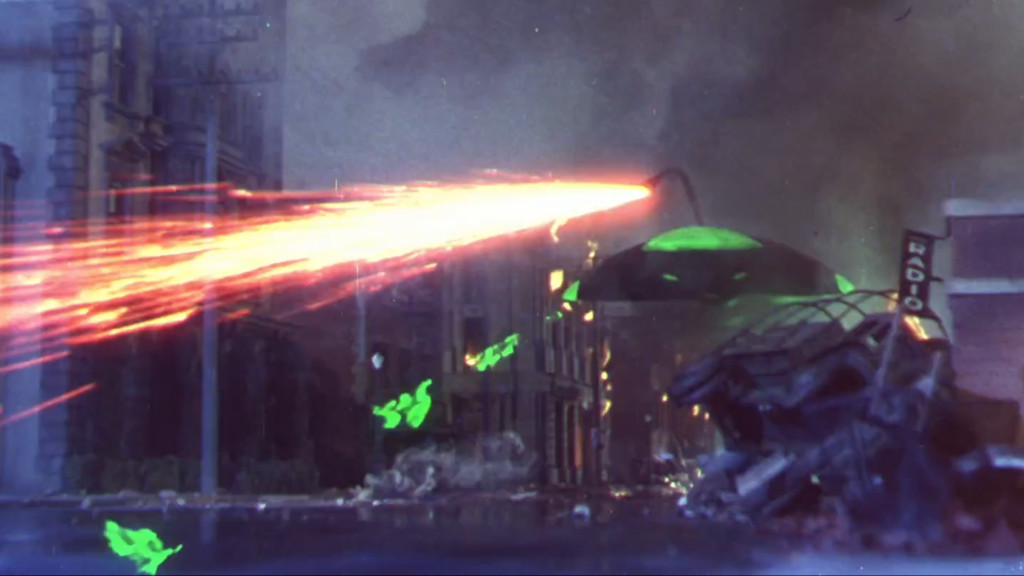

But first, let’s recognise that whatever its flaws, The War of the Worlds was like nothing that anyone had ever seen before. It is a landmark of cinema and one of the true milestones of science fiction movies. There were SF films made in the fifties that had better characters, better social analysis, better dramatic arcs, were better written, better acted and better directed. But none had the visual and cultural impact that The War of the Worlds had. This was the Star Wars of its generation. It was the first true SF Technicolor spectacle on the epic scale, bringing all the kitsch and effects to the audience in startling explosions of colour. The iconic manta ray-inspired design of the sleek copper alien war machines with their green, blinking lights and their, all-seeing, mercilessly destroying cobra heads have since become legend. Audiences were flabbergasted by the visual effects, coupled with amazing sound design and supported by Leith Stevens’ bombastic score. And it was the first film to portray aliens as truly alien. Up to this point, aliens had mostly been recognisably human, with rubber or papier mache heads. Even Gort, the iconic robot from The Day the Earth Stood Still, was clearly a very tall man in a costume. But when the aliens of The War of the Worlds are finally revealed, the audience felt that this was what an actual alien looked like — no way that was a man in a suit. With its single, large glowing RGB-eye mounted in top of a snail-like body and its spindly arms and suction cup fingers, its icky, slimy skin covered in pulsating veins, this was something truly alien. It is also worth remembering that The War of the Worlds was the very first film in which the audience got to witness first-hand an actual alien invasion, rather than dealing with a single scout or messenger. Whatever critique i have of the film, please bear in mind that at no point do I wish to diminish its rightful place as one of the most important, visionary and influential science fiction movies in history. And it is righfully loved and cherished by fans all over the world.

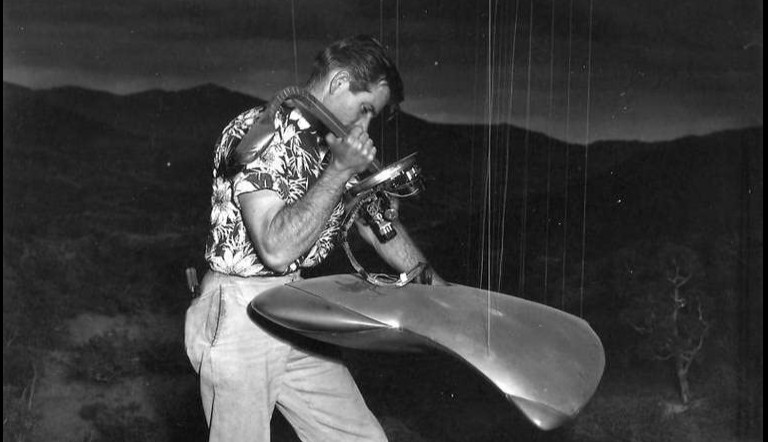

The iconic war machines of the Martians were designed by legendary art director Albert Nozaki. As a puppeteer, George Pal had initially intended to recreate the walking tripods of Wells’ story, but decided it would be too costly and time-consuming. The script goes out of its way to make clear that Nozaki’s flying war machines aren’t actually ”flying”, but are supported by some sort of ”magnetic” beams, and one scene even shows three flickering beams descending from one of the machines, in effect making them tripods with invisible legs. The large miniatures were made out of copper and were supported by 15 wires, some of which provided the electricity for the gadgets inside, such as the retractable ”neck” with the electronic eye and the lights on the wing-tips. Working on the miniatures of the movie was Marcel Delgado, the constant companion of stop-motion animator Willis O’Brien, who of course worked on films like The Lost World (1925, review) and King Kong (1931, review).

The film’s the large effects team was led by Gordon Jennings, winner of two Oscars and nominated eight times. It is true that some of them were borrowed from The Day the Earth Stood Still, such as updating the black smoke used in Wells’ novel to a disintegration ray, and the disintegration effects look very similar to the ones in the 1951 movie. These were all cel-animated, but the most memorable Martian weapon, the burning ray, or rather spray, from the cobra head, was a practical effect done against blue screen. In fact, it was as simple as it was genius. The sparks seen on screen were the sparks from a melting welding-wire blown past or towards the camera with a blow-torch. The draw-back to this effect is that it looks like the range of the weapon is limited to a few metres. But it must have been quite something to see it blown-up all over the screen, added over the live-action in the movie theatre.

Another very cool, but super-simple effect was the ”electronic shields” of the war machines, that show up very quickly in a couple of scenes. These were ordinary bell jars used for displays, that were filmed against blue screen, and superimposed over the Martian vehicles. The wonderful matte paintings of space and the planets, as well as a glimpse of Mars, were made by astronomer and artist Chesley Bonestell, ”the father of space art”, a frequent George Pal collaborator. The other matte painter on the film was the brilliant Jan Domela, who won an ”honorary Oscar” along with Gordon Jennings for the effects on Spawn of the North in 1938, before there was a category for special effects. Splendid are also the miniatures of the destruction of Los Angeles. Pal’s choice of Byron Haskin as director was obviously inspired by the fact that Haskin had worked as a cinematographer and a special effects creator before he became a director, as Pal knew how important the effects were going to be for the film. Also on the effects team was people like double Oscar winner and process photographer Farciot Edouart and miniature photographer Cliff Shirpser.

Cinematographer George Barnes was a Hollywood veteran who had worked with a slew of the great directors, including Cecil B. DeMille, and won a Golden Globe for his work of The Greatest Show on Earth. The colour of the film is beautiful, and much emphasis is laid on it, from the orange skies, glowing with alien activity to the way the red-green-blue lights from the Martian eye wash over Robinson and Barry in the house they are trapped in, the multi-coloured powders mixed in the explosion to recreate the nuclear bomb and the poisonous green of the Martian disintegration rays. In Haskin’s colour work and scenes of destruction Fernanco Croche of of Cinepassion sees the influences of Hieronymus Bosch’s hellish visions and Edvard Munch’s flaming skies and green hills. Mark Bourne of the DVD Journal writes that ”The richly saturated three-strip Technicolor /…/ probably caused the entire nation to stop dreaming in black-and-white.”

Of course a modern viewer will feel that many of the effects are dated and crude, and there are problems. At least on the new, remastered copies of the film, the wires that support the war machines are clearly visible in many scenes. There’s also the fact that the machines have a very ”miniaturey” feel to them and look like toys in a certain light. The light is a constant problem, as there are very visible blue matte lines in some shots, and the blue light from the blue-screen reflects in the copper coating of the vehicles – on the other hand this does give them a sort of alien glow, which adds to their menace.

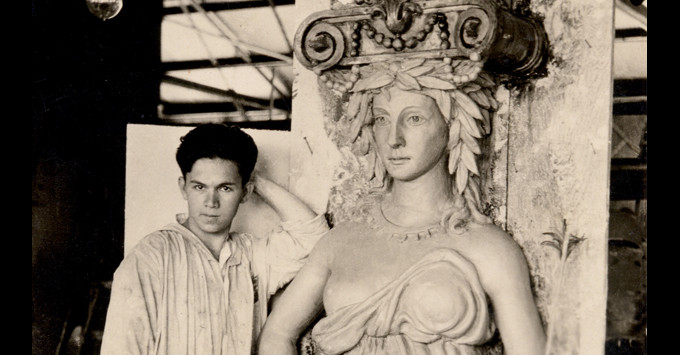

The Martian was designed by Nozaki, and built by Paramount’s makeup artist and creative genius, Filipino immigrant Charles Gemora, best known as one of the legendary gorilla actors of Hollywood’s golden age. Head of Paramount’s makeup department was Wally Westmore, but he only did the makeup for the actors, or at least planned it, probably. The makeup heads were often the only credited makeup artists on the film, even though they sometimes had very little to do with the actual work on the movies. Gemora received no official credit for building (and actually redesigning) the Martian.

His daughter Diana Gemora, 12 years old at the time, tells – Tom Weaver, who else – about the creation of the alien in the book A Sci-fi Swarm and Horror Horde. She recounts how her father stormed in after a day at work, ate his dinner, and swooped her away, as he sometimes did, to his studio at Paramount, explaining he had done six months work on the alien, only to be told that it was too big to fit in the set of the house where the protagonists were trapped. He had now torn it apart and had to redo the whole thing – in one night. Diana and Charles worked frantically through the night with a wooden frame, chicken wire, plaster bandages, foam latex, tape, electronics, paint and glycerine and had the thing done by eight in the morning. However, the the latex hadn’t cured properly yet, and as they wheeled the thing out of the studio bits and pieces were falling off and the whole Martian was barely holding together, ”a big mound of taped-up Jell-O”.

But it got on set, and Charles got into the suit, as he also played the Martian. He worked on his knees on a wooden dolly that was being dragged around on wires by the stage hands, and he was completely blind in the suit. Diana, 12 years and with no sleep, still with the curlers she had put in her hair the evening before, was called in by her father to operate the compressor that made the veins in the Martian’s head and arms pulsate. She crawled under the stage floor with her compressor and pumped whenever Charles shouted ”Pump, pump!” She thought the whole thing was absolutely hilarious – her dad hidden behind the suit on the trolley, the Martian a heap of uncured foam latex ready to fall to pieces at any moment, and the stage hands yanking Charles around, so that at one point the whole thing almost tipped over. And that would have been the end of it.

Now, the alien does look a bit flimsy when you know the story behind it – but one is even more impressed by the look of it when one knows it was a one-night rush job. It is such a testament to Charles Gemora’s genius that he was able to make such an elaborate being in one single night. Granted, the electronics were made earlier, as were the wire-controlled arms and fingers. But still – the unique look of the alien and the pulsating veins and everything. Haskin also wisely hides it in shadows most of the time, and only shows it in quick flashes. But it was so convincing that Diana writes that she was genuinely frightened by it when she saw the film, even though she had built it.

The special effects received an Oscar – awarded to the film as a whole, not Jennings and the team, for some reason. This continued George Pal’s winning streak – Destination Moon and When Worlds Collide both won the same award. But The War of the Worlds was also nominated for best editing and best sound recording, although the term ”sound recording” was something of an archaism even in 1953, when much of a film’s sound was done with effects and overdubs. The soundscapes of The War of the Worlds should rightly have taken home the Oscar, if not for anything else, then for the eerie sound of the Martian heat ray. That strange, otherworldly subdued ”chirping” laid with a ghostly echo has since been reused infinitely in sci-fi films (and others). The one effect I can think of off the top of my head is the sound of the bleeping motion detectors that the crew use to spot aliens in Aliens (1986), which is almost exactly copied from The War of the Worlds. (I am now listening to Leith Stevens’ soundtrack album, and Martian Heat Ray is actually credited as one of his compositions). There are a lot of brilliant sound effects in the film. According to John Johnson’s book Cheap Tricks and Class Acts the scream of the Martian when he escapes from the axe-flinging Barry was produced by scraping dry ice across a contact microphone and mixing it with a woman’s high-pitched scream played in reverse. Effects for war machines and death rays were made with multiple electric guitars played in reverse. The humming of the war machines were fabricated by using a tape recorder echo machine feeding output to input, resulting in a strange, oscillating echo.

The acting in the movie is OK. Never better, seldom worse. It’s professional, but the dialogue does the players few favours. Gene Barry in the lead as Dr. Clayton Forrester is appropriately hunky, but also halfway believable as a scientist. Barry is utterly charming in a fifties macho sort of way throughout the film, even if Haskin reportedly wasn’t very happy with his performance. And it is true that he is quite wooden. But he has a sort of Brad Pitt cool about him, that makes him the draw in every scene he is in. Ann Robinson plays the romantic interest in the movie, and I’m sure she is a wonderful actress, but to be frank, she doesn’t really shine in this film. But that’s simply because all her character really does is scream, cry and act hysterical. Credit where credit’s due, though – Robinson has one of the most impressive screams of any of the scream queens of cinema. Haskin reportedly commented only ”Oh, my goodness” after he had heard it for the first time. Steven Spielberg called it the best scream in the business, save for the original scream queen Fay Wray’s. When Robinson does have some dramatic scenes, she is pretty OK, considering she really only had a few minor stage roles and uncredited bit-parts under her belt.

The movie received mainly good reviews. Even The New York Times, notoriously un-friendly to sci-fi in the past, praised the film for its sense of adventure and special effects. A.H. Weiler wrote: ”The War of the Worlds is, for all of its improbabilities, an imaginatively conceived, professionally turned adventure, which makes excellent use of Technicolor, special effects by a crew of experts and impressively drawn backgrounds”, and called the film ”suspenseful, fast and, on occasion, properly chilling”. Variety also writes about the ”socko special effects”, praises the cast and the ”logical love-story”, and gives the film 3 out of 4 stars.

My main problem with The War of the Worlds aren’t the stiff acting nor the dated effects, its insipid take on women nor, really, its pathetic, tacked-on religious pathos, even if these last two are especially grating. Sure, one can excuse these with the fact that the film is “of its time”, but no. Compare, for example, the female lead character in The Day the Earth Stood Still: a strong, independent, smart and caring mother who plays an integral part of the story by making decisions and doing actions. In The War of the Worlds, Sylvia is present only as eye-candy and being a damsel in distress. And when she is done being in distress, she cooks breakfast for the leading man. But still, this is not my main problem with the film. It is the fact that the script foregoes everything that Wells wanted to say with his novel and ends up with a completely meaningless script.

A lot of things happen in the film, and people do stuff all the time, but none of it is of any consequence. Sure, this is the way the book was written. But the book was a satire. The film is not a satire, and instead frames the story as a conventional war or adventure picture, with a hero and his comrades working hard against impossible odds and prevailing in the end. But the problem with framing the film in this way is that they don’t prevail in the end. All they do is meaningless and none of their actions have any consequences. For example, a good deal of the movie is taken up by the subplot which begins when Clayton hacks off the alien tentacle probe when he and Sylvia encounter the Martians, and finds a cloth smeared with Martian blood. He takes these to his fellow scientists, and they are able to analyse how the Martians see, and study the composition of the alien’s blood. In any other film, this would provide a key to defeating the enemy. But here the whole subplot is redundant, as the movie resolves itself with a famous deus ex machina. Likewise redundant are all the characters: no-one in the film experiences any personal growth or awakening, nor any new understanding. There is no philosophical or moral conclusion to the movie. It just ends, leaving the viewer with a strange sense of disappointment, trying to figure out what we actually learned from this. Actions have no consequences. The clergyman sacrificing himself is of no consequence. Neither is the fact that Clayton captures alien technology. The much-deliberated decision to use atomic weapons against the aliens have no repercussions, and neither does the fact that the mob destroy all the scientists’ research, because the research was meaningless in the first place. The lead characters never have to confront any of their beliefs or values, nor are their courage or determination really tested. Clayton is a hero from the beginning to end, and Sylvia is afraid from the beginning to the end. In order to create some sort of personal drama, the screenwriters have added the story of Clayton and Sylvia getting separated, and Clayton searching for her among the chaos — but even that has no consequence, as she was safe inside a church the whole time.

The acts themselves are all solidly written as action-pieces and hold up well as isolated stories, quite enjoyable to watch. The movie is still enjoyable as a retro action movie, and one can whole-heartedly appreciate the wonderful effects sequences and the skill and care with which they were made. I can understand that audiences at the time forgave the dramatic flaws, as they would simply have been blown away by the grandeur of the visuals. But the writing really is atrocious, and it all stems from the fact that the screenwriters didn’t respect — or perhaps understand — the source material. Wells’ story had no heroes — in the end, the protagonist simply gives up. The War of the Worlds was written as a satire meant to puncture the puffed-up notion of British exceptionalism and hold a mirror to the intended audience’s participation in genocide and colonial warfare. It was also a reminder from the scientifically minded Wells of humanity’s smallness in the face of nature and the universe. Even the most powerful creatures in the solar system are slaves to the laws of nature, and in the end, nature reclaims what is hers. As the Martians were in the end outdone by bacteria, so too will the British Empire crumble to dust, as must all empires. In this, the Brit is no different from the Hottentot, for all his huffing and puffing. But this is something that George Pal and his colleagues have failed to understand. Instead, they huff and puff to no avail.

Perhaps surprisingly, the contemporary genre press was often very forgiving of Hollywood taking substantial freedom with the source material. Surprisingly, as these magazines primarily dealt with genre literature, publishing the best of available SF stories at the time, and well aware of the abundance of intelligent and well-written SF in the fifties. However, when it came to films, these publications seem to have been happy as long as SF in general was introduced to a general audience, and seem to have been under the assumption that the general audience simply wouldn’t “get” the more complex content. Thus, Thrilling Wonder Stories at the time of the film’s release had few negative words to say about The War of the Worlds. Writer Pat Jones notes the changes made to the ending, but concedes: “it’s the best way to satisfy the general audience”. Jones concludes: “All in all, this is the outstanding science fiction film made to date. The color, intelligent direction by Byron Haskin and remarkable art, all point to finer, more artistic science fiction movies in the future. We’re glad to see it happening.”

The War of the Worlds is one of the films selected for preservation by the US Library of Congress, and in 2004 received the 1954 Retro Hugo Award for short films (under 90 minutes). The film was nominated for Oscars for editing, sound and special effects, and won the last. In 1978 Pal and The War of the Worlds were entered into the Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Hall of Fame. Today the film has a 7.1/10 score on IMDb, an 89% Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a 78/100 score on Metacritic. These are very good numbers, but not stellar. Compare with The Day the Earth Stood Still, which rates as 7.7/10 on IMDb and has 95% Tomato count.

Unlike me, many critics today are willing to have oversight with the film’s flawed script, and rightfully praise The War of the Worlds’ splendid effects, artwork and menacing atmosphere. Chuck Bowen at Slant magazine gives the film a full 5/5 stars in a recent review: “Producer George Pal’s 1953 sci-fi landmark The War of the Worlds is particularly gorgeous and intense, centered around various fears that still haunt us today. The film’s opening is by itself more beautiful than many contemporary genre movies in their entirety.” Michael Drucker at IGN awards in 9/10 points: “Technically, this film remains a masterpiece today. While perhaps not as scary as it was in 1953, the amazing sound and visual effects still stand up.”

Under The Radar magazine also gives the film a glowing review, calling it “breathtaking”: “War of the Worlds combines light and color in a way to create that magical, movie look that only the best Technicolor films can.” An interesting point that the magazine’s critic Austin Trunick points out is that the 2018 DVD remaster has brought the film back to its original visual standard: previous digital restorations have brighter and sharper than the original theater copies would have been. For example, most of us have seen versions of the movie with the lines holding the Martian war machines clearly visible, but Trunick points out that this because of the way the film has been restored previously: they wouldn’t have been visible to the audiences in 1953, because the prints were darker.

Still, Trunick also points out why it’s a film that makes modern audiences chuckle: ” Yet, even while mankind stands on the brink of destruction, the movie spends plenty of time allowing the hunky, heroic scientist to romance the sweet girl-next door. Tonally it’s like you dropped Rock Hudson and Doris Day into the middle of Aliens, but that’s part of the movie’s wonky charm.”

However, not all critics are as blown away by the “original” The War of the Worlds as the above mentioned. TV Guide has a 3/4 review: “Though it’s bogged down by a stiff cast, a yawn-inspiring conventional romance, and a sappy religiosity, it remains a landmark in the history of special effects”. Entertainment Weekly gives it a B, or the equivalent of my 7/10 rating, calling out the “sub-Shatner acting by Gene Barry“, but also notes “effective thriller frissons provided by barely glimpsed Martians and realistically rendered alien war machines”. AllMovie gives it 3.5/5 stars, with critic Mike Cummings citing a “simple story” and “pedestrian acting” combined with “brilliant pacing and stunning special effects”. Time Out notes that the film “still works pretty well”, but also writes: “Too bad about the wooden cast, the tackily conventional romance, and a draggy religious message”.

The War of the Worlds is a film that I would like to like more than I actually do, partly because it is such a visually stunning movie and such a landmark of the SF genre. There are so many wonderful innovations in the film, and it helped shape an entire genre. But, sadly, as a work of drama it doesn’t hold up because the film tries to be something that the original story was never intended to be, and in throwing out almost all of Wells’ important themes, it fails to satisfyingly replace them with others. This results in a script that fails on a very fundamental level of storytelling. Sure, it’s exciting, but after the excitement has died down, one asks oneself: “What was this all about? What did we learn from this?” And the answer is: “Nothing”.

To date, over 100 films or TV series have been based on H.G. Wells’ work, and by 1953 over a dozen feature films and as many shorts had been made from his novels and stories – he also wrote a number of scripts for shorts in the twenties. The first substantial sci-fi film in history, A Trip to the Moon, was an uncredited mishmash of ideas from both him and Jules Verne. A British, sadly lost, movie was made on First Men in the Moon in 1919, and The Island of Dr. Moreau was turned into the German Die Insel der Verschollenen in 1921 (review). Paramount, who produced The War of the Worlds, also held the rights to The Island of Dr. Moreau, which was made into an excellent film in 1932, as Island of Lost Souls (review). Wells didn’t like the film, as he thought it put too much emphasis on the horror elements. He did, however, like Universal’s splendid take on The Invisible Man in 1933 (review), made by British Frankenstein director James Whale. However, one can imagine he was not too fond of the franchise the film launched, that mostly had very little to do with the literary source. Generally, he didn’t like the way his stories were portraid on film, and tried his own hand at screenwriting for the British epic Things to Come (1936, review), based on his own book, produced by Alexander Korda and directed by William Cameron Menzies. Although visually marvellous and thematically ambitious, the film suffered badly from Wells’ pompous and preachy script.

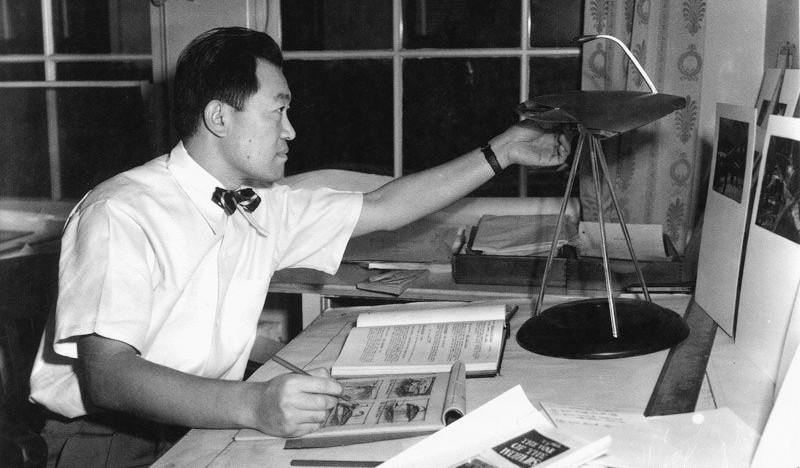

Gene Barry (born Eugene Klass, he took his moniker from actor John Barrymore) was a ”song and dance man” from the New York stage who drew up to Hollywood with his family after ending a tour in the South, and managed to secure a contract with Paramount on a whim in 1951, just three days after arriving in Los Angeles. According to an obit in The Telegraph, the news came as such a shock to his wife that she fainted and fell into a pool. After a few TV guest spots, he secured his first lead in The Atomic City, and was then shoved directly into The War of the Worlds, with a salary of 1 000 dollars a week, or between 9 000 and 13 000 dollars today, depending on how you count. In comparison, lead actress Ann Robinson made 125 dollars a week.

Barry appeared in five more Paramount films, and some low-budget indie features like the sci-fi movie The 27th Day (1957, review), where he again played the lead, and headed down a successful TV career in the late fifties, which lasted all the way into the 21st century. In 1955 he appeared on a couple of episodes of Science Fiction Theatre, and had a role in a episode of the revamped The Twilight Zone on 1985. He also played one of the three rotating leads in the TV show The Name of the Game, which featured the occasional sci-fi episode. However, he shot to TV stardom in the title role of his first big TV series Bat Masterson (1958-1961), continued by Burke’s Law (1963-1966), he further had the lead in The Adventurer (1972-1973), but after that he mainly appeared as a guest star, although Burke’s Law was revived for one season in 1994. He more or less retired after this. In an interview with my favourite film historian Tom Weaver, he claims that although he had a very successful TV career, he had some regrets about accepting the role as Bat Masterson, since it, in his opinion, killed his movie career. In the book Earth vs. the Sci-fi Filmmakers: 20 Interviews Barry says: ”I had a fine television carer – but I had a lousy movie career [laughs]! It’s the truth. In those days, it was a negative stamp, making the move into TV.”

On the other hand, the films he played in after The War of the Worlds weren’t exactly stellar, and he often got pushed down to fourth or fifth billing, so in all honesty TV probably saved his career. Barry also did a number of stage performances and toured the world as a singer, and even released a crooner album. His performance in La Cage aux Folles on Broadway in 1983 was a smash hit and earned him a Tony nomination. Barry often played wealthy, debonair characters, and the roles were mirrored in real life, where he would always dress in an impeccable suit and drive around town in a Rolls-Royce. Barry won a Golden Globe for his work on Burke’s Law, a Golden Boot for his work in westerns and has a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his stage work.

Weaver interviewed Barry just before the Steven Spielberg remake of War of the Worlds (2005) went into production, and asked him if he would be interested in a cameo if approached. Barry responded: ”Of course I would take it. It would be thrilling.” Well waddayaknow? Along with co-star Ann Robinson, Barry had a cameo in the movie, where the pair played the mother and father of Tom Cruise’s on-screen wife, showing up in the final scene of the movie. Barry passed away in 2009.

In a really funny interview in Double Feature Creature Attack – again by Tom Weaver – Robinson explains how she cheated her way into showbiz by pretending she was a stunt woman – which meant she actually became a stunt woman, at least for a year or so. Robinson was part of the so-called Golden Circle of Paramount, who were paid peanuts, but had weekly wages, and basically sat around and did little scenes in a room called ”The Fishbowl” once a week for directors and producers who would then decide whether to use them in a particular film or not. After a particularly impressive double performance in The Fishbowl, Pal hired her as the female lead. Robinson is very open about the fact that she didn’t know anything about film acting at the time, and praises Byron Haskin for helping her with the performance. She also reveals that she wore a hair peace, which explains why her feathers are never ruffled even when on a day-long escape from a war zone.

Robinson had another major role in Maxwell Shane’s refugee thriller The Glass Wall (1953) by Warner, but was released from Paramount just after the The War of the Worlds had premiered, and was actually re-hired to do the promotion on the Eastern seaboard. She then moved almost straight into TV, and is best remembered for her role as Queen Juliandra on the kiddie show Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954). She was quite busy with TV in the mid-fifties, but then tied the knot with a matador and moved to Mexico in 1957. When she returned, not long after, Hollywood had passed her by: ”I just ruined it, I blew it. I should have stayed around and paid more attention. Now I know why they call it ‘the business’, because it is a business. I thought it was all fun and games and glamour, and I didn’t take care of it as a business”, she tells Weaver. She dropped out of acting in 1963 to focus on her family.

However, she put together a big gala night for Paramount for the 25th anniversary of The War of the Worlds, which to the studio’s surprise became extremely popular. This gala helped her back into the business, and she did a few roles on TV, when in the late eighties she heard on the grapevine that Paramount was putting together a TV series based on The War of the Worlds, and was able convince the studio to let her reprise her role, which she did on three episodes. Robinson enjoyed herself, and recalls she was treated like royalty on the production. Along with Robert Clarke of The Man from Planet X (1951, review) fame, she again reprised her role in the strange patchwork movie called Midnight Movie Massacre (1988), about a monster that eats everybody in a movie theatre showing a remake of Space Patrol. She did another, even stranger, patchwork spoof in The Naked Monster (2005) – which was actually an updated version of a fan-film called Attack of the B Movie Monster, originally made in 1984, and was cram-packed with old fifties sci-fi stars, like Kenneth Tobey, Robert Clarke (again), and Robinson’s The War of the Worlds co-star Les Tremayne, reprising his role as General Mann. It is unclear whether Robinson was in the original film or did additional footage in 1992 or 2002. And as mentioned above, she also had a cameo in the 2005 version of War of the Worlds. That was her last film role, but she is still around and kicking in January 2016, at 86 years of age. Here’s a really nice video interview with her from 2009,

Another interesting actor in the film was Les Tremayne, primarily known from his radio work in the thirties and forties, when he appeared in some of the most popular radio dramas in the country. At one time he was voted one of the three most distinctive voices on American radio, alongside Bing Crosby and Franklin D. Roosevelt. At one time he appeared on 45 different shows in a single week. Tremayne plays the no-nonsense general Mann in The War of the Worlds, and it is actually one of the best portrayals of one of these army brass types in the fifties sci-fi films I have seen.

Tremayne kept working in radio, TV and film up until the nineties, although in his later years he mostly did voice work. He appeared in numerous science fiction films: he narrated Forbidden Planet (1956, review), played one of the leads in The Monolith Monsters (1957, review) and did the rocket launch countdown for From the Earth to the Moon (1959). He played the lead in The Monster from Piedras Blancas (1959), and starred as one of the astronauts who land on Mars in Ib Melchior’s psychedelic cult film The Angry Red Planet (1959). He did numerous voices for the English dub of King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) and had another starring role in The Slime People (1963). He guested an number of sci-fi TV series in the sixties and dubbed a role in the English version of Antonio Margheriti’s War Between the Planets (1966). One of Tremayne’s longest streaks in a single TV series was his role as Captain Marvel’s mentor in Shazam! (1974-1977). He did voice work on the 1985 animated movie Starchaser: The Legend of Orin, and, as mentioned, appeared in The Naked Monster.

In her interview with Weaver, Robinson recalled how thrilled she was to work with two of her childhood heroes, George Pal, who was the creator of the Puppetoons animations, and Les Tremayne, who she had grown up listening to on the radio.

Higher billed than his role required, Robert Cornthwaite can be seen as one of the three scientists who are on a fishing trip when the meteorite falls in the beginning of the movie. Cornthwaite was already a sci-fi star by this time, after his chilling performance as Dr. Carrington in The Thing from Another World (1951, review). For more on him, please see that review. We’ll just mention that he also appeared in The Naked Monster. The third scientist is played by Sandro Giglio, who had a small role in When Worlds Collide.

Paul Frees, a renowned voice actor (who also has face for film), composer and sound editor who not only acted in or provided voices for over 300 films or TV series, but also worked as one of those well-kept secret actors in Hollywood who would do overdubs in post-production whenever extras needed voicing or a film star’s lines needed changing and the star couldn’t make it to the sound studio. So adept was Frees at doing voices and accents, that in some instances on dubbed films or animations, he wound up having a four-way conversation with himself. The War of the Worlds is his best known role where he’s actually seen. He or his voice also appeared in The Thing from Another World, When Worlds Collide, a number of Godzilla dubs, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), The Cyclops (1957, review), The Mysterians (1957, review) dub, Beginning of the End (1957), The 27th Day, The Monolith Monsters, The H-Man (1958, review) dub, Space Master X-7 (1958), The Time Machine (1960), The Last War (1961) dub, Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), The Absent-Minded Professor (1961), Gorath (1962) dub, Dimension 5 (1966), King Kong Escapes (1967) dub, Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), The Milpitas Monster (1976) and Nothing Lasts Forever (1984).

In the beginning of the movie there’s a scene with the three stooges of the little town, who keep a nightwatch over the meteorite as the rest of town are square dancing. They represent the old, stupid and greedy redneck geezer, the young, reckless kid and the quota Hispanic (the only minority character in the film). These are the first victims of the Martians, as they approach with a white flag, figuring even aliens would know the meaning of the white flag. The kid is the best of the lot, and is played by none other than William Phipps, a lot more juvenile and clean-shaven than he was when he did such an impressive job as the lead in Arch Oboler’s nuclear holocaust film Five (1951, review). It’s a shame his career never took off, since I think he had a lot of potential. Phipps passed away in 2018, at the respectable age of 96.

Jack Kruschen plays the Hispanic man of the group. Apparently the movie was so white-washed that they couldn’t even get a Hispanic actor, but had to go with a Canadian. Kruschen was a prolific character actor in radio, TV and film, best known for his role in the romcom The Apartment, for which he was nominated for an Oscar for best supporting actor. Kruschen also appeared as an astronaut alongside Les Tremayne in The Angry Red Planet, and might be remembered as the magician Eivol Ekdal on the Batman series (1966), and appeared in a number of other sci-fi shows.

In a small role as a cop at the crash site we see noted German-American character actor Henry Brandon (real name Heinrich von Kleinbach), who specialised in playing villains and characters of non-American ethnicity, often European, but also Asian, Arab, African, Native American and South American. He is remembered for his role as Silas Barnaby in the Laurel and Hardy film Babes in Toyland (1934), Fu Manchu in Drums of Fu Manchu (1940), Major Ruck in Edge of Darkness (1943), Giles de Rais in Joan of Arc (1948), M’Tara in Tarzan and the She-Devil (1953), as well as ”Indian” chieftan in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). He regularly appeared on stage and on TV and had a career that spanned all the way to his death in 1990. Although a popular character actor on TV, his movie career seems to have come to a sudden halt in the sixtes, perhaps because word was getting out about his homosexuality. And it saddens me so much that even in 1990 his long-time companion Mark Herron was not named as one of those he was ”remembered by” in his obituary in the New York Times.

Among the extras we spot Emmy-nominee Ned Glass, silent film charmer Ivan Lebedeff, Golden Globe winner, Oscar nominee and most of all: Morticia Addams; Carolyn Jones, also known as Teddy Belicec in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), Golden Boot winner Bob Morgan, stunt legend David Sharpe and Japanese character actor Teru Shimada.

According to his daughter Diana, makeup and special effects creator Charlie Gemora was one of the great innovators of Hollywood makeup, and worked as an apprentice to the great god of horror makeup, Lon Chaney. Diana says Charlie came up with the first studio blood that didn’t stain, the first whipped foam latex, lipstick in tubes, falsies and the first Kleenex box. But being the generous and unassuming guy that he was, he never patented or took credit for things, but freely shared his inventions with his colleagues, some of whom later took credit for his work. Unfortunately this streak of bad businessmanship also spilled over to the rest of his life, as he was a heavy gambler ans is said to have won and lost a million dollars seven times over.

Gemora started as a sculptor, and for example did much of the sets on The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), The Thief of Bagdad (1924), The Phantom of the Opera (1925) and Noah’s Ark (1928). He also created and started performing in his first gorilla suit in the early twenties. His suit was first used on The Lost World, although not with him in it. He first acted on film in the suit (as far as we know) 1927, and had at least 40 gorilla roles, although the number is probably much higher, as the gorilla and creature performers were almost never credited. He also designed the suits for The Colossus of New York (1958) and Curse of the Faceless Man (1958). He played a bear in Road to Utopia (1945) and another alien in I Married a Monster from Outer Space. He worked as makeup artist on films like Island of Lost Souls, The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Dr. Cyclops, Double Indemnity (1944), A Place in the Sun (1951), The Ten Commandments, Around the World in Eight Days (1956), I Married a Monster from Outer Space, Hands of a Stranger (1962) and Jack the Giant Killer (1962). He passed away in 1961, just 58 years old. Diana Gemora helped Charlie on many of his films, but was naturally never credited. There is a documentary called Charlie Gemora – Uncredited in post-production as of January 2016, so keep a look out for that!

To finish this long post off, here are some stats on the head honchos of the movie. George Pal was actually nominated for Oscars for best short cartoon seven times for his Puppetoon films, and received an honorary Academy Award for his work in animation. Both his films The Time Machine (1960) and 7 Faces of Dr. Lao were nominated for Hugo Awards. The War of the Worlds was entered into the Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films Hall of Fame in 1978, and Pal received a Special Award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films in 1975. After The War of the Worlds, he produced another four sci-fi movies, the ambitious but problem-ridden Conquest of Space (1955, review), The Time Machine (1960), which he also directed and is regarded by many to be his finest work, Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), which he also directed, and The Power (1968), again with Byron Haskin.

Pal was loved by all who worked with him, and Ann Robinson heaped praise on him in her interview with Weaver, calling him ”the most wonderful man in the world”, ”a kind, sweet gentleman”. Legend has it that he was so sweet and probably naive, that he was constantly being ripped off by studios stealing his ideas. It got to the point that Pal in his later years moved his office to his home so that people wouldn’t come looking over his shoulder at what he was up to, and making their own movies about it. For more on Pal, please check out the review of Destination Moon.

Byron Haskin was four times Oscar nominated, and later directed Conquest of Space, From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), The Power, and produced the very first, rejected Star Trek pilot The Cage in 1965.

Gordon Jennings won two actual Oscars for non-sci-fi films in 1942 and 1943, and a bunch of technical awards. He also worked on two of my favourite sci-fi films: Island of Lost Souls and Dr. Cyclops (1940, review), as well as When Worlds Collide. Jan Domela was his constant companion. Bonestell worked on Destination Moon, When Worlds Collide, Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), Conquest of Space (1955) and the TV series Men Into Space (1959-1960). Second art director Hal Pereira won one Oscar and was nominated for a whopping 21 other films. Pereira also worked on When Worlds Collide and Conquest of Space, as well as The Space Children (1958), The Colossus of New York (1958), I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), Visit to a Small Planet (1960), The Nutty Professor (1963), Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), The President’s Analyst (1967), and Project X (1968).

Janne Wass.

The War of the Worlds. 1953, USA. Directed by Byron Haskin. Written by Barré Lyndon. Based on the novel The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells. Starring: Gene Barry, Ann Robinsin, Les Tremayne, Robert Cornthwaite, Sandro Giglio, Lewis Martin, Houseley Stevenson Jr., Paul Frees, William Phipps, Vernon Rich, Henry Brandon, Jack Kruschen, Cedric Harwicke, Ned Glass, Joe Gray, Charles Gemora, Carolyn Jones, Ivan Lebedeff, David McMahon, James Seay, David Sharpe, Bobby Somers, Wilhelm von Hohenzollern, Anthony Warde. Music: Leith Stevens. Cinematography: George Barnes. Editing: Everett Douglas. Art direction: Albert Nozaki, Hal Pereira. Set decoration: Sam Comer, Emile Kuri. Costume design: Edith Head. Makeup supervisor: Wally Westmore. Astronomical art: Chesley Bonestell. Sound recordists: Gene Garvin, Harry Lindgren. Sound director: Loren L. Ryder. Special effects: Edward A. Sutherland, Barney Wolff. Visual effects: Gordon Jennings, Jan Domela (mattes), Marcel Delgado (miniatures), Farciot Edouart, Cliff Shirpser. Martian costumes: Charles Gemora, Diana Gemora. Produced by George Pal, Frank Freeman Jr. & Cecil B. DeMille for Paramount Pictures.

Leave a comment