In 1950 Hollywood finally produced its first first serious, big-budget space film. With the help of luminaries like Robert Heinlein, Hermann Oberth and Chesley Bonestell, future SF icon George Pal produced a visually stunning but dramatically stale epic, heavily influenced by the red scare. 6/10

Destination Moon. 1950, USA. Directed by Irving Pichel. Written by Alford Van Ronkel, Robert Heinlein, James O’Hanlon. Inspired by novel by Heinlein. Starring: John Archer, Warner Anderson, Tom Powers, Dick Wesson. Produced by George Pal. IMDb: 6.3/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 64/100. Metacritic: N/A.

Destination Moon from 1950 is one of those films where you sort of have to tread a bit carefully when reviewing: it is considered by many to be one of the most important films in science fiction, however it influenced the industry and the audience more than it did the actual films that followed in its wake. Key players in the foundation of NASA cite the film as an inspiration, and it opened the door for science fiction, which had up until then been assigned to cheap kiddie serials and B horror movies, into the big league in Hollywood. But although it is admired by many, it is loved by few.

The driving force behind the first serious space film made in the United States was George Pal, born György Pál Marczincsak in Hungary – one of the many Hungarians who dominated Hollywood in the middle of the last century. This was only the second live action film that Pal directed, but he wasn’t exactly new to the business, having been nominated for Oscars a whopping seven time for his famous Puppetoon animations. Exactly why the animator decided to start producing lavish science fiction films is unclear to this reviewer, but in one interview Pal mentioned that he wanted to ”tell more”, and the short animations just weren’t enough. In the same article he mentioned that he wished to push the envelope, both for science and for the human condition. His ultimate goal was to make the viewers of his movies go forth from the theatre and build a better world.

In this blog I have previously complained about Hollywood’s reluctance to take science fiction seriously – a strange thing to say these days, but we had to wait until 1950 for an all-out science fiction film to take the step from the cheap serial format to full length feature films. And when it was finally done, it was done outside of the major studio system, by George Pal’s own company, in association with another smaller company, Eagle-Lion Films.

Before Destination Moon there was the 1918 Danish film Himmelskibet, or A Trip to Mars (review), a rather fantastic tale of a propeller-driven spaceship flying to Mars, where the protagonists find a utopian society. In 1930 Austrian Fritz Lang made Frau im Mond, or Woman in the Moon (review). On the one hand a rather fantastic tale of a ragtag party going to the moon in search of gold. However, the science of the actual spaceship and the space flight was almost as accurate as, in some ways more accurate than, Destination Moon. In the Soviet Union Yakov Protazanov made his social allegory Aelita (review), about a revolutionary (in the literary sense of the word) trip to Mars to see Queen Aelita in 1924. Vasili Zhuravlyov followed this up with the juvenile movie Kosmichesky Reys, or Cosmic Voyage in 1935 (review). This film was based on sound scientific basis, even if the filmmakers took some artistic license with the spacecraft. It was, however, probably the most accurate description to date of the actual conditions of the moon up to that date. H.G. Wells and Alexander Korda followed up this in Britain in 1936 with the social prophecy Things to Come (review), which ended in humanity sending their first rocket to the moon. All these films were costly, high-profile films made by some of the countries’ most respected studios and filmmakers. But in the United States the studio bosses just wouldn’t budge: science fiction was for goggle-eyed boys and wouldn’t attract a mainstream audience, was the philosophy. George Pal proved them wrong.

From the onset Pal was determined not to make a fantasy film. This was supposed to be ”a documentary of the near future”, as he put it. The science had to be as accurate as it could get, and for that he hired the people who knew the science. Most important of these was science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein. He was by this time not yet a household name, and had only published a few juvenile novels and a number of short stories. He was, however, well known by readers of sci-fi magazines, where he had published a number of stories, many of them based in hard science. Pal took his cue from Heinlein’s first published novelette, Spaceship Galileo (1947), because of its science-based description of a spacecraft and the actual space trip. However, the book told the story of three boys and a professor who made a rocket in their backyard and went to the moon, only to discover that the Nazis had fled there after WWII and built a space station. Unfortunately we had to wait until 2012 and the independent Finnish schlocker Iron Sky for the moon Nazi movie. Instead, Heinlein took the science of Spaceship Galileo, and combined it with aspects of his unreleased short story The Man Who Sold the Moon (1951), and worked together with James O’Hanlon and Alfred van Ronkel to create the final script, along with other technical advisers, such as rocket engineer Hermann Oberth, who had also worked on Woman in the Moon, and astronomer and artist Chesley Bonestell, who made the film’s stunning matte paintings.

As such the film was completely without precedent in Hollywood. It created massive public interest even before filming had concluded. TV crews visited the set, the filmmakers did numerous appearances on radio and were interviewed for newspapers and magazines, and Life magazine even published a massive spread with Bonestell’s space and moon artwork. Even more than in the film, people were interested in the actual possibility of a moon landing. Remember, this was seven years before the Soviet Union launched Sputnik and eleven years before Yuri Gagarin made his lap around the Earth. With the advances in rocket technology that the Germans had made during WWII, serious political and scientific questions were being raised about what it could mean if one cold war bloc reached the moon before the other, and this is also where the film kicks off.

George Pal, a naturalised American, had very strong patriotic feelings toward his new home country and seems to have been just as paranoid about the Soviet war machine as anyone in Washington. Even though Heinlein’s ideological swings are famously hard to pin down, he was at this time of his life a patriotic libertarian with a strong anti-communist stance. The film follows General Thayers (Tom Powers), who works on satellite rockets for the government alongside Dr. Charles Cargraves (Warner Anderson), buts get sacked when their costly experiments fail time after time. The problem, Cargraves is assured of, is that ”They” have infiltrated the military and are sabotaging the rockets. ”They” and ”foreign powers” are mentioned frequently in the film. Although ”The Soviet Union” or ”communists” are never mentioned by name, the allusion isn’t difficult to grasp.

Thayers and Cargraves team up with hotshot airplane manufacturer Jim Barnes (John Archer), and together they decide that American combined industry will put the first men on the moon, since it is a job too big for the government. As Thayer explains: if ”They” succeed in getting there first, ”They” will build a missile base there, and thus control the world. Therefore, America must claim the moon in the name of world peace.

All this is explained during a rather protracted meeting with leaders of American industry, where the scientific basics of space travel is laid out in an infomercial starring none other than Woody Woodpecker, and narrated by director Irving Pichel. The rocket, Woody explains, will be powered by nuclear fuel that heats water, turning it to gas, which will then propel the rocket upward and forward. This infomercial and Thayer’s patriotic speech turn all the industrial leaders from sceptics to believers, and the space race is on.

From that point on, it’s pretty much standard moon movie fare. Problems occur that mean the trio must take off earlier than expected. ”They” have infiltrated the government and try to stop the project by spreading fantastic tales of the dangers of nuclear radiation. ”Propaganda!”, Archer sneers. The radio engineer falls sick, so his assistant, dimwit Bowery boy Joe Sweeney (comedian Dick Wesson in his first film) takes his place, reluctantly. ”You’re all wet! The thing won’t woik!” he informs the scientists. In this Brooklynite’s opinion, the gargantuan steel rocket is too heavy, it’ll never leave ”Oith”. And thus we have our compulsory comic relief character. But lo and behold, the rocket actually woiks, even if the technicians would have a hard time understanding Joe’s readings of ”thoity-foive” over the controls, and to his astonishment it lifts from Oith just as planned.

The technical aspects are all well presented, from G-forces to weightlessness. Everything is clearly explained by the scientists to Joe, who acts as the audience’s stand-in. A novel and superbly daft idea is introduced in magnetic boots that prevent the passengers from floating. A mid-flight mishap occurs when a radar antenna jams and the crew takes a space walk in their magnetic boots on the hull of the ship. Barnes makes a noobie mistake and leans out over the edge to check on the rockets, lets go of his safety line for better reach, leans too far, loses his magnetic grip and floats away. The situation is resolved by a rescue by oxygen tank acting as propellant – a scene that has since been replicated ad infinitum, even by Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

They land on the moon, but Barnes botches the landing and uses up too much fuel. The crew wander around on the moon for a while taking pictures and looking for uranium, when the home team informs them that they have to lose 1 000 pounds to compensate for the fuel loss if they’re going to be able to get back home. They then strip the rocket down to its bare bones, but are still 120 pounds too heavy, and it looks like one of the team members has to stay behind on the moon …

One of the strengths of this film is the science, or at least it was when it was released. There are numerous gaffes that seem ridiculous today, but weren’t necessarily back in the day – at least to a scientist. To film critics, however, the film was pure juvenile fantasy. New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, for example, wrote that the film ”smacks of the ventures of Buck Rogers or the earlier imaginings of Jules Verne”. In his opinion, man could not, would not and will not reach the moon. ”The thing won’t woik!”, to paraphrase a certain character. Crowther also laughs about people becoming ”free orbits” in space, misunderstanding the line about the space ship being in free orbit, and finds the ”inter-space suits” amusing. He also laments that there are no beautiful women or Russian space stations on the moon, betraying the condescending attitude toward science fiction in the film industry. Peter King of The Spectator tried to shoot down the movie’s science by writing so much gibberish that a seventh-grader would have shot him down in an instant. In his opinion, to be able to break free of the Earth’s atmosphere, one would have to travel ”somewhere near the velocity of light”. If anything, these comments at least illustrate how little a normal audience at the time knew about or understood the concept of space travel, or outer space in general – which may excuse the lengthy science monologues of the movie, as well as the Woody Woodpecker animation. (As a sidenote: Woody Woodpecker creator Walter Lantz and George Pal were close friends, and Pal tried to include Woody in as many of his films as possible. He can be seen in When Worlds Collide [1951, review], The War of the Worlds [1953, review] and The Time Machine [1960], among others.)

Even though Heinlein himself had written in his books about the two- or three-stage rockets that were used in Woman in the Moon, and which ultimately ended up being used for the actual moon flight in 1969, for this film the filmmakers have opted for a sleek one-stage design driven by nuclear fuel, although the one-stage design would be highly impractical, as it would carry lots of unnecessary weight, and would be impossible to land tail-first, not least on an uneven moon surface. But the filmmakers probably chose the design because it looked cool. And it does even to this day. The design became a prototype for space rockets with its streamlined, beautiful exterior and the triple tail fins which doubled as landing gear.

As opposed to the rivalling film, the low-budget Rocketship X-M (review), which was rushed into theatres a month before Destination Moon premiered, the cockpit didn’t however, rotate on a gyro, keeping the floor ”down” at all times. As I pointed out in the review of that film, this would be utterly pointless, since it doesn’t matter one bit which way the floor is when you are weightless. For Rocketship X-M, the solution was made because the production team didn’t have the time or the money to show weightlessness. This was a problem that the team behind Destination Moon also encountered. It HAD been done – with wires – in previous films, and there is a short instance where Joe seems to be rigged in wires, and for a couple of minutes we see some of the actors in frame from the waste up, ”floating” in the cabin, probably standing on moving cranes. The film does use piano wire for some of the moon walks and the scene outside the spaceship, but this is only used for wide shots, and the wires would probably have been visible in the cramped cockpit. Kosmichesky Reys handled this problem by creating an absurdly roomy spacecraft. Destination Moon basically takes the same approach as Woman in the Moon, by showing a few brief moments of weightlessness, then clamping the actors down with magnetic boots. In Fritz Lang’s film the spaceship floors were covered with straps for the actors to slide their feet in. However, Destination Moon takes the concept a stage further by creating a cabin set that can be rotated, so that the actors can seem to be walking on the walls – basically it is the age-old trick of turning the set and the camera upside-down or on their sides.

Another queer thing for a modern viewer is the use of nuclear power and steam jets for propulsion. The idea is not completely absurd. The steam jet technique is used for some smaller rockets today, but the water is heated with electricity and not nuclear fission. The choice to go with nuclear fuel was probably partly political. Despite the film’s talk of world peace, it takes a stance for a strong defence, in fact a military build-up against the ”foreign threats”, and the US government is often ridiculed for not caring about the ”foreign threats” and ”not investing” in ”these kinds of things in peace-time”, even though in reality the military expenditure in the States was rising rapidly. As stated above, the film also portrays the warnings about nuclear radiation as ”propaganda”. To paraphrase my review of the anti-nuclear film Rocketship X-M: ”[In 1950] radiation was often portrayed more as a nuisance than a life-threat. This was partly because not even scientists were perfectly clear on how radiation works. At the time the US government was conducting secret radiation tests on soldiers and criminals. The government did know that radiation potentially had devastating and long-lasting effects. This, however, was covered up the US government because of the ever-cooling cold war and the American desire to step up the nuclear program and engage in all-round rearmament. This was also the stance of many sci-fi films.” /…/ ”To quote on of my favourite movie critics, Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant: ‘Hollywood was most likely patriotically parroting the Atomic Energy Commission’s ‘safe nuke’ public relations because they believed it with the rest of us. Radiation in Science Fiction became a completely fantastic, all-purpose Genie in a Bottle that made ants grow and people shrink. Not until 1959’s On The Beach did the notion resurface that radiation was a bad thing that could do really nasty stuff” The casual ease with which the scientists of Destination Moon dismiss any danger in the fact that they will be sitting on top of repeated nuclear explosions in outer space, protected only by a thin metal hull, is hilarious today, but wasn’t necessarily in 1950.

Note also the fact that the only actual scientific data they seem to collect on the moon is the fact that it contains uranium. There is some talk about scientific tests on the moon, but that is not the main focus of the trip, neither do these scientist seem to bring other equipment than an astronomic camera for shooting the sky and a Geiger counter. To be fair, the expedition is cut short by the message that they have to start tearing the rocket apart to lighten the load, but still the main purpose of the trip seems to be political and military. Dr. Cargraves solemnly claims the moon for the United States, which seems to settle the matter. One question lingers, though: what will prevent the Russkies from building a missile station there anyway? If they intend to shoot missiles at the United States they surely won’t be deterred by a dry scientist’s proclamation that he got there first? Of course, this doesn’t matter for the film, which is more or less an extension of the war-time propaganda movies.

What I’ve tried to illustrate above is that the things that the movie got wrong were choices they made, either out of practical necessities or political reasons. There is so much the film gets right, such as the silence of the vacuum of space, most of the technical aspects of a space flight, the gravity of the moon, the look of the moon – although both Heinlein and Bonestell grumbled at the idea of making the surface of the moon look like dried and cracked mud, since that’s completely wrong. But production designer Ernst Fegté wanted to give the surface of the moon more texture.

The sheer mass of information, the revelations about space, the moon and space flight, were some of the aspects that blew the audience away. Another was the visuals of the movie. Most impressive were the massive matte paintings of the moon, some of which were built on wheels so that they could be dragged in front of the camera for long panning shots. And one has to remember that for many people this was the first colour science fiction film they had seen. Just the idea of seeing a colour shot of Earth at the time (a painting, of course, but still) was astounding – there were no satellites back then, there simply was no photograph of the Earth – and then seeing space and the moon. Admittedly, we don’t see much of space, other than stars against a velvet background. This is one of the pitfalls of the film – we get no sense of the vastness or wonder of space. The stars actually look like they are glued to a flat backdrop. In fact, they were holes in a black backdrop that was lit from behind.

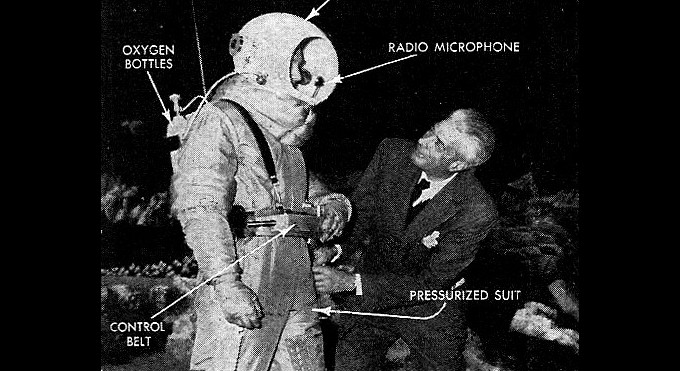

The design of the spaceship is incredibly iconic, although not scientifically sound. The rest of the film has a few design flaws, such as the above mentioned cut-out stars. The space suits look way too flimsy and resemble padded winter sports overalls more than space suits (they were, however re-used in Flight to Mars (1951, review), the TV series Space Patrol (1950), and the spoof Amazon Women on the Moon (1987). The great big space camera looks a bit cardboardy. The G-force bunk beds with their leather cushions are less than convincing (although very much preferable to the canvas bunks of Rocketsip X-M).

The special effects were designed by Lee Zavitz, who had previously burned down Atlanta in Gone with the Wind (1939), crashed a plane in Foreign Correspondent (1940) and convinced the world that Charles Laughton was a pirate in Captain Kidd (1945). He would go on to work on two more sci-fi films: From the Earth to the Moon (1958) and On the Beach (1959). He also worked on Around the World in 80 Days (1956), The Alamo (1960) and the comedy classic The Pink Panther (1963). Zavitz was responsible, among other things, for the gimbal that rotated the cockpit and the impressive wirework that helped the actors walk around the hull of the spaceship and bounce around on the moon, as well as the free-floating effects when Barnes loses his grip on the rocket. Zavitz was rightly awarded with an Oscar for his work – but it does have its flaws. The free-floating scenes are extremely clumsy and static, and the upside down set is a nice piece of engineering, but it probably looked much cooler than it was difficult. As long as you build a set that is sturdy enough, flipping it over isn’t really that difficult. It used electric motors, but it could just as well have been done with a crane and a forklift. We never actually see the set rotating, which would have been a cool scene, but the flipping is always 90 degrees and done with editing. Scenes with the actors seeming to be ”standing” on different ”floors” is really just by having one of the guys lying on the floor, pretending to be standing and leaning against a wall. Novel for an American audience, yes, but when you have seen the same thing done in silent movies made 20 years earlier, it isn’t that impressive.

But these are all aspects that could have been overlooked had they only been spices added to a good film. The problem is that the actual film doesn’t hold up to its backdrop. The script is less a movie script than it is an essay on space flight and a political pamphlet rolled up in one. The only interesting character in the movie is the dimwit mechanic, and he really isn’t that interesting, more like improbable. The other three main leads are completely interchangeable. We get to know absolutely nothing about them or their personalities during the whole film, which is a feat, as we spend the whole time locked up with them in various rooms or cockpits. The acting isn’t all that bad, but it’s just that the actors have nothing to work with. There’s a spark of emotion at the end when they have to deal with who stays on the moon, but by then it’s a little too late.

The lack of interesting characters, the technical dialogue, the stretched-out scenes and the static cinematography make for quite a boring film, despite the subject-matter. Apart from some stunning moon mattes, the film also fails to convey any sense of the wonder of space. There are some words of awe at the sight of Earth, but apart from that the characters seem quaintly uninterested in the fact that they travel through outer space. Even when they are taking a space walk the script writers manage to turn the conversation into a lecture in physics. The moon itself is more or less reduced to an ”Oh boy!” from Joe and a comment on how barren it is from Cargraves. Sure, they didn’t have the tools to make Stanley Kubrick’s fantastic space shots, but that shouldn’t have hindered the screen writers to at least make an effort.

There are those who defend the film by saying that it’s impossible to understand what an impact it had when released in 1950. True, but that’s really not the point here. I was awed by the sheer scope of Metropolis (1928, review) and impressed by the epic futuristic imagery of Things to Come. I was dazzled by the strangeness of the Martian architecture in Aelita and chuffed to bits by the gothic darkness of Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review). This film never gives me the shivers, and unfortunately feels a bit flat. The colour helps, and it was probably much more dazzling when seen on a big screen in all its sharpness. But even if the imagery and the sight of the space and the moon in vivid Technicolor dazzled audiences back then, it is not enough to make this a top-notch movie.

Despite the New Your Times‘ Bosley Crowther’s sniggering at the plausibility of the moon journey, he gave credit where credit was due: “However, we’ve got to say this for Mr. Pal and his film: they make a lunar expedition a most intriguing and picturesque event. Even the solemn preparations for this unique exploratory trip, though the lesser phase of the adventure, are profoundly impressive to observe.” However, he laments that that things take a turn for the dull as soon as the rocket reaches the moon, and that the return trip is “downhill all the way”: “For, in tossing away much equipment in order to lighten the ship for its take-off from the moon, the gentlemen apparently jettisoned what they had left of a script”.

Bob Thomas of the Associated Press was on the same page as Crowther: “The scientific aspects are supposed to be authentic and seem so to the layman. It’s too bad the dramatic aspects are not as convincing. The plot is more Model T that rocket-propelled.”

However, science fiction fans were happy. SF writer Arthur C. Clarke did an enthusiastic write-up in Journal of the British Astronomical Society: “[T]his [is a] remarkable exciting and often very beautiful film—the first Technicolor expedition into space. After years of comic strip treatment of interplanetary travel, Hollywood has at last made a serious and scientifically accurate film on the subject, with full cooperation of astronomers and rocket experts. The result is worthy of the enormous pains that have obviously been taken, and it is a tribute to the equally obvious enthusiasm of those responsible.” Sam Merwin Jr., editor of the pulp magazine Startling Stories, “thought it a very fine job indeed. The plot was the trip itself, the photography so superb that it had, save in a very few brief sequences, the semblance of reality. Save for a necessary and somewhat hoked-up ending, Destination Moon had to us the impact of a documentary film.”

Today, the film’s legacy is often touted, but it’s generally revered more for its scientific accuracy and its technical aspects than for its dramatic content, which is not infrequently referred to as “dull”. Destination Moon has a 6.3/10 rating on IMDb and a 64/100 rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Both are decent numbers but not quite what one would expect for a groundbreaking classic — which the film certainly is. Kim Newman at Empire magazine gives the movie 2/5 stars, writing that it “deserves its historical place but has worn less well than its scrappier, pulpier competition”. TV Guide gives it 3/5 stars, calling it “routine, even dull”, but “an important step in the genre’s evolution”. And AllMovie likewise gives the film 3/5 stars.

Nevertheless, there are those who feel that the film is better than its somewhat shoddy reputation. Andy Webb at The Movie Scene gives Destination Moon 4/5 stars and praises its hard SF approach: “The fact that for the most it tries to deliver realism in how space travel would work is brilliant especially considering that back in 1950 man had not yet travelled in space yet set foot on the Moon.”

Richard Scheib at Moria also awards the picture 4/5 stars, and bemoans the fact that so many critics call the film “dull”. According to Scheib, these accusations “reveal a reviewer’s lack of empathic projection”. Scheib has a point, and it’s one that I’ve also tried to make here: At the time, no film audience has seen space in colour and a film depicting a scientifically plausible journey to the moon would have been exciting. The fact that we don’t feel this excitement has to do with that fact that we’re watching in 70 years later, wiser by the fact that we have visited the moon and are used to seeing images of space. Scheib also argues that the fact that the film has an almost documentary feel should make it more, not less, exciting in the critic’s eyes: “surely the fact that Destination Moon can be accused of being too close to the real thing to be interesting is just indicative of how much of an imaginative leap it was”.

Since Scheib is taking pot shots at other critics, I feel I might make him taste a bit of his own medicine. First of all, as I have outlines above, even critics at the time of the release of Destination Moon were torn, with many calling the film, in so many words, “dull”. And just because an idea itself is novel and exciting, doesn’t mean that a film about the idea, no matter how accurately it is portrayed, is necessarily riveting. But the argument that Scheib is working up to is that since space exploration is exciting per se, a the film accurately describes the activity of space exploration, then the film is also, per se, exciting. This is of course an absurd notion.

Mark R. Hasan at KQEK is another defender of the film, albeit with perhaps a few more reservations that Webb and Scheib. Hasan praises the technical and artistic aspects of the movie, including Leith Stevens’ score, the sound design and the matte work. He does however point out the script’s “wonky morality” and “dated” science, as well as the “template” characters. Still he concludes that “the reason Destination still functions as escapist fodder is its core theme of space exploration, and while the effects aren’t jaw-dropping anymore, there’s no denying the theme of adventure, and the visual and aural artistry are what grabs the viewer”.

Christianne Benedict at Krell Laboratories also writes that “Destination Moon is immediately striking for its production”. But she also writes: “Destination Moon is also immediately striking for its politics. This is a paranoid right wing fantasy, one not hidden behind a veneer of distance provided by genre.” She continues: “Regardless of its design and its politics, Destination Moon has one central problem: its characters act mostly as mouthpieces and ideologues […] Because of this, it’s dramatically inert. […] This is at the heart of this film’s relative obscurity. It was first in space, sure, but it’s not thrilling. You need character and drama for thrills, and that’s something this film lacks.”

Similar notions are brought up by Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum. Giving it 2.5/5 stars, Lovell finds the movie fun, but not without “its share of slow spots”. He concludes that “Destination Moon is a more than passable entry in the durable genre”. James O’Ehley at The Sci-Fi Movie Page also notes that “the movie’s biggest problem […] is its plodding pace and nondescript characters”, giving it 2/4 stars. And finally, while Richard Cross at 20/20 Movie Reviews doesn’t have anything particularly bad to say about the movie, which he calls “enjoyable”, he still only awards it 1/4 stars.

John Archer who plays what might be considered the lead as the industrialist was born Ralph Bowman and worked with this and that in Hollywood before winning an acting competition for RKO, and the prize was a contract and a name: John Archer: ”I went from being a Bowman to an Archer”, he later joked. Handsome and not without talent, he was however considered a bit bland. He toiled away on reasonably successful and well-made films, avoiding sinking into the B movie swamp for many years, and called it quits in the seventies to go into the transportation business with his brother. After Destination Moon he had guest spots on a number of anthology and sci-fi series, including The Twilight Zone and the legendary West and Ward Batman (1966-1968), and appeared in Kurt Neumann’s She Devil (1957, review).

Deep-voiced and solemn Warner Anderson appears as the most interesting of the actors, but his character Dr. Cargraves is even less developed than that of Barnes’. Excluding a few guest spots in TV shows, Anderson shunned sci-fi during his long film and TV career, ans is best known as newspaper publisher Matthew Swain on Peyton Place (1964-1969), which he also narrated.

Tom Powers as the aged but vigorous General Thayer is perhaps the best actor of the lot, trying desperately to bring life to the wooden lines he is forced to put in his mouth. The best scene of the film is one in the very beginning where Thayer visits Barnes in his office and immediately makes himself at home, knowing where to find Barnes’ cigars, chatting all the way while barns stands in a walk-in bathrool washing his hands. There are very nice touches in the scene, such as Barnes vigorously drying his hands before shaking hands with Thayer, the way we immediately feel the friendship and long history between the men just by their demeanor and their small actions. It’s a wonderful scene in which both actors are great. If the rest of the film would have maintained this focus on character and everyday situations, it could have been such a great film. It tries sometimes, making Thayer and Joe space sick, a small scene of lunch on the ship and so forth, but the movie is never able to recapture the humanity and grace of that second splendid scene.

Dick Wesson as Joe Sweeney does his shtick and is much needed as something at least remotely human to hold on to in the dull affair. His comedy is occasionally funny, but the character is written like a cartoon and never feels believable. Even his Brooklyn accent is phony, he grew up in Boston.

Erin O’Brian-Moore is the only woman appearing in the film apart from Barnes’ secretary. For some inexplicable reason she was billed alongside the four leads in the beginning of the movie, although she only appears for about a minute when she bids her husband Cargraves goodbye. The producers probably thought they needed a female name to put on the posters. But make no mistake – this is a sausage fest from beginning to end. Rocketship X-M may have had a few misogynistic overtones, but at least they stuck a female scientist on their space ship. In Pal’s world space travel is the realm of men (as it indeed was in the United States up until the mid-eighties). The rest of the cast is utterly non-consequential: prolific bit-part actor Franklyn Farnum turns up as an uncredited factort worker. Farnum appeared in over 400 films between 1916 and 1961, often uncredited, including a number of sci-fi movies in the fifties, such as The Man From Planet X (1951, review), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), Red Planet Mars (1952, review), Invasion U.S.A. (1952, review), The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review) and Tobor the Great (1954, review).

Irving Pichel was an actor-turned-director, whose best film prior to Destination Moon was probably the influential and disturbing The Most Dangerous Game, about a madman who hunts people for sport on his private island. That film, however, was co-directed by King Kong (1933, review) director Ernest B. Schoedsack. On Destination Moon Pichel had the help of top-notch cinematographer Lionel Lindon, who would go on to win an Oscar for Around the World in 80 Days. But despite all the trick shots and the space panoramas, they are quite lost at sea when it comes to filming the movie. The film lacks any sort of pace and simple scenes like people putting on their boots or descending on a ladder are dragged out to infinity. It doesn’t help that so much of the action is played out against flat matte paintings that don’t allow for filming from different angles, so often we simply get a single take of a scene from one angle, going on forever. Pichel also seems to have an aversion to close-ups and most of the film consists of wide shots and boring mid-range shots, and all in all the cinematography feels static.

Lionel Lindon went on to film George Pal’s second space flight film Conquest of Space (1955, review) as well as the exploitation film The Black Scorpion (1957, review). Leith Stevens’ score is suitably bombastic and to create some suspense and emotion when the dialogue and cinematography fails to do so. Stevens went on to score Pal’s When Worlds Collide (1951) and The War of the Worlds (1953), as well as The Werewolf (1956, review), World Without End (1956, review), Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), The Night the World Exploded (1957, review), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review), I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958), The Phantom Planet (1961), Mutiny in Outer Space (1965), The Human Duplicators (1965), Women of the Prehistoric Planet (1966), The Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966), as well as a number of sci-fi TV series. Production designer Fegté found himself designing for top-notch films like Monster from Green Hell (1957, review), The Amazing Transparent Man (1960) and The Time Barrier (1960), as well as the Adventures of Superman TV series.

George Pal, of course, went on to make some of the most successful science fiction films of the fifties, mostly as producers, and sometimes as director. His other sci-fi films were When Worlds Collide (1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), Conquest of Space (1955), The Time Machine (1960), Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961) and The Power 1968). Pal is rightly considered as the father of the American space film, such was his influence on the genre. The War of the Worlds is now considered a typical example of the schlocky fifties science fiction film, although this was not Pal’s intention – his goals were always higher. Herein lies Pal’s greatness. He constantly tried to push the envelope of what could be done on a movie screen, both in terms of subject-matter and in the realm of special and visual effects. For him, films like The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine were highly serious films and he treated them as such, without taking short-cuts or winking at the audience.

As seen in Destination Moon, though, it wasn’t always artistically satisfactory. He often deviated widely from his source material, stuffing his films with American patriotism and religious overtones, were such weren’t warranted. Atheist H.G. Wells would have turned in his grave, had he known that Pal turned his highly irreverent book The War of the Worlds into a religious narrative. Pal also completely missed the leftist social allegory of The Time Machine, turning it instead into a pretty simple-minded anti-war movie. The Time Machine is, however, the one of his films that has aged best and can probably be considered his crowning achievement, which is in a way something of a personal victory for him, since it was one of the few films he directed himself. Among all the words of praise for this visionary producer, there are also some critical voices. Gary Westfahl writes: ”Pal was numb to the rhythms of film narrative and unable to attract or inspire capable actors; he regularly seized upon wonderful source material and shamefully butchered or trivialized it, as if unable to comprehend what made it special; even the special effects that he devoted most of his attention to could be wildly inconsistent, ranging from the impressive to the laughable.” To sum it up, Time Out does it well: [Destination Moon is] ”characteristically thin on plot and characterisation, high on patriotism, and impressive in its colour photography and special effects”. All in all, I must confess that although I admire the film and respect its legacy, I was more fond of the low-budget exploitation movie Rocketship X-M, that beat it to the cinema in 1950.

Janne Wass

Destination Moon. 1950, USA. Directed by Irving Pichel. Written by Alford Van Ronkel, Robert Heinlein, James O’Hanlon. Inspired Heinlein’s novel Rocket Ship Galileo. Starring: John Archer, Warner Anderson, Tom Powers, Dick Wesson, Erin O’Brien-Moore, Franklyn Farnum, Everett Glass, Kenner G. Kemp, Knox Manning, Mike Miller, Irving Pichel, Cosmo Sardo, Grace Stafford, Bert Stevens, Ted Warde. Music: Leith Stevens. Cinematography: Lionel Lindon. Editing: Duke Goldstone. Production design: Ernst Fegté. Set decoration: George Sawley. Makeup: Webster C. Phillips. Production management: Martin Eisenberg. Technical adviser on astronomic art: Chesley Bonestell. Sound: William H. Lynch. Animation (Woody Woodpecker): Walter Lantz, Fred Madison. Produced by George Pal for George Pal Productions.

Leave a comment