Himmelskibet, released in 1918, is he first serious movie to deal with a trip to a distant planet. Poetically filmed and featuring lavish Martian designs, this Danish space opera is at heart an endearing pacifist message in a time when the first world war was ravishing Europe. (7/10)

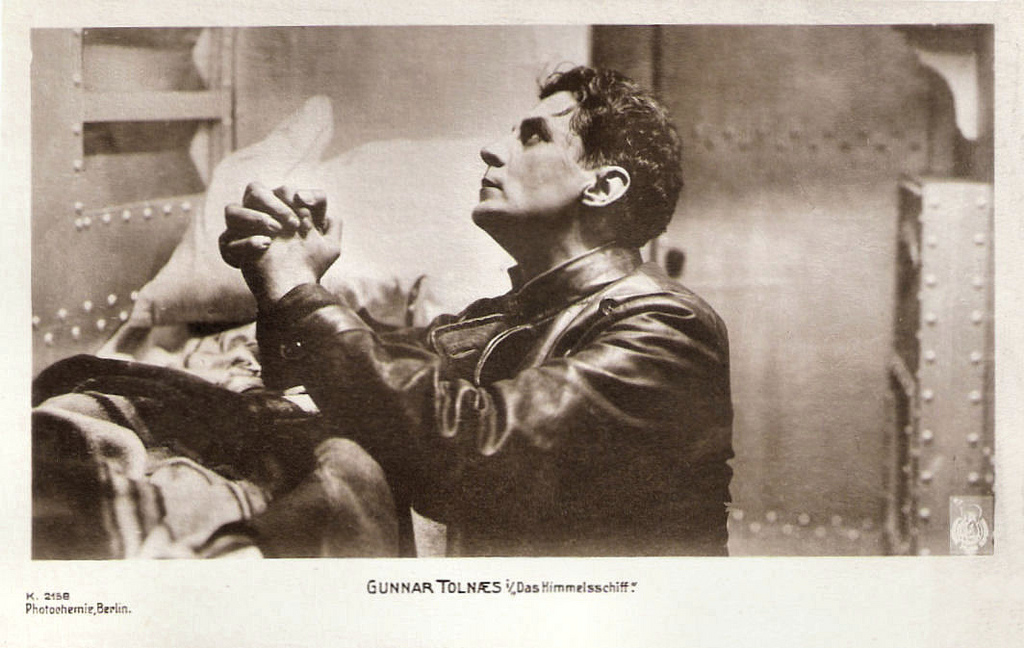

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet). 1918, Denmark. Director: Holger-Madsen. Written by: Sophus Michaëlis, Ole Olsen. Starring: Gunnar Tolnæs, Alf Blütecher, Lilly Jacobsson, Nils Asther. Produced by Ole Olsen for Nordisk Films Kompagni. IMDb score: 6.8. Tomatometer: N/A. Metascore: N/A.

This little gem is one of the most curious science fiction films between Georges Méliès’ 1902 short A Trip to the Moon (review) and Yakov Protazanov’s influential Soviet space fantasy Aelita (1924, review). Although not generally known for their huge contribution to science fiction, Denmark was something of a front-runner on an international scale for serious sci-fi films in the early days of the genre – with August Blom’s impressive post-apocalyptic epic The End of the World (review) in 1916, and Holger-Madsen’s interplanetary pacifist pamphlet A Trip to Mars, as well as Danish actor Olaf Fønss’ magnificent turn in the German films series Homunculus (1916, review).

Both Danish sci-fi films were made when World War I was raging in Europe, and the Golden Age of Danish film production was coming to an end. It might be difficult to fathom today, but for a short period of time Denmark was actually one of the very few film industries capable of competing with Hollywood and France. According to Collins’ Film Encyclopedia: “Despite the small size of its native market and its relatively limited resources, Denmark reigned supreme for several years (1909-14) as Europe’s most prosperous film center. Its films rivaled those of Hollywood, for popularity on the screens of Paris, London, Berlin and New York.” Eventually the problem for Nordisk Films Kompagni (today Nordisk Film, or Great Northern) became that they had too many films on their hands, and couldn’t sell them fast enough in a Europe ravaged by war. Another reason was that Denmark’s main export partner, Germany, quickly built up their own film production during WWI. By the end of the decade Denmark suffered such a bizarre thing as movie inflation, which caused the Danish movie business to all but collapse under its own weight.

While the apocalyptic The End of the World (Verdens Undergang) told the story of two pious and moral survivors of a disaster brought on by a passing comet, A Trip to Mars has a more optimistic view on life, depicting an expedition to Mars, where we find a utopian society based on pacifism. It was a pamphlet and a message of hope for humanity during the great war. This is both the film’s strength and its weakness.

It is clear from the beginning that this film is not to be taken in complete seriousness – not when we are introduced to characters with names like Avanti Planetaros, his father Professor Planetaros, his sister Corona Planetaros, her fiancée Dr Krafft and the dubious Professor Dubius. It becomes even clearer that this is a symbolic parable with the overly dramatic Delsarte Method (hand-to-forehead acting) used by the actors, and the melodramatic language of the intertitles.

Sea captain Avanti Planetaros (star actor Gunnar Tolnæs) returns from a great adventure and seeks … new adventures! at which his father, the professor (Nicolai Neiiendam), informs him that the next great discovery lies … out there! “In space, there are thousands of mysteries… planets that we long for, and that long for us!” This fires up the good Avanti – that much is obvious, as he lunges into a frenzy of energetic pointing toward the heavens, not just with his hands and arms, but with his entire body and soul! As another reviewer points out, one can only hope that with the advent of the talkies, someone found Tolnæs a job pointing at things, because he is really good at it (in fact he got so rich by playing maharajahs that he retired of his own will in 1929 . His friend Dr Krafft (Alf Blütecher) joins forces with him to build a craft that can fly all the way to Mars, while the ”friend” Professor Dubius (Frederik Jacobsen) is doing all in his power to ridicule the idea.

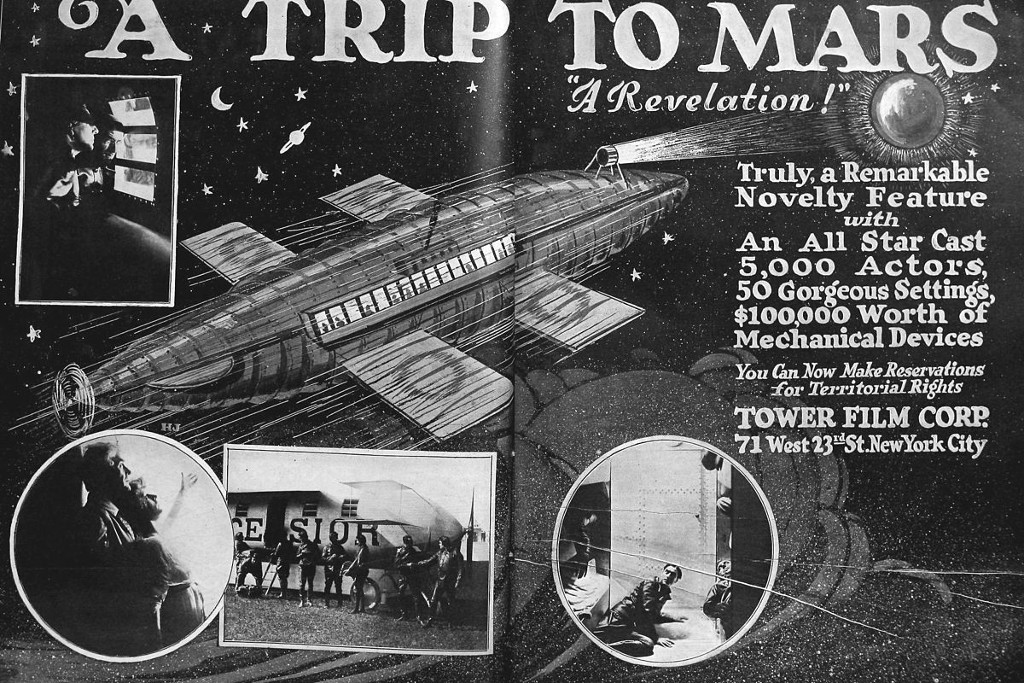

Undeterred our heroes soldier on, and after two years they can reveal the magnificent craft, with the name EXCELSIOR in giant lettering on the side. A modern viewer cannot help but giggle at the sight of the ungainly and rickety thing that looks like a cross between a dirigible and a sausage, equipped with biplane box wings and a hilariously small propeller at the back – mirroring the fascination with aviation at the time. But it sure does fly, and with an international crew assembled, they take off to the skies. Although it is unclear how the craft flies through the vacuum of space, and why the absence of gravity doesn’t seem to affect the crew, we do get a bit of realism when the film fast-forwards six months, and reveals a crew that is becoming increasingly grumpy about not yet having reached their destination. Led by a burly American alcoholic by the name of Dane (Svend Kornbeck), most of the crew decide to stage a mutiny, and just when it looks as if things are about to go sour, the ship is suddenly grabbed by the Martian tractor beam.

The explorers arrive on a Mars that looks suspiciously much like Earth, only like Earth of ancient Greece (actually it is a quarry outside Copenhagen). It is inhabited by a race of humanoids dressed in white togas and silly hats who are blessed with the gift of telepathy. A whole horde of them seem to have been casually strolling the grassy hills when the Earthmen arrive, and greet the travellers heartily. Our heroes are invited to dinner (still standing in the hills) and are surprised that the Martians are strictly vegetarian. Avanti sends for some canned meat and wine from the ship, at which the head Martian (Philip Bech) – a wise man, we are told – sniffs disapprovingly and asks how the meat is ”procured”. The man of action that Avanti is, he promptly whips out his revolver and shoots down a bird that just so happens to fly overhead – and it is a mighty huge whopper of a duck that THUMPS down right by his feet. We all see where this is going – this is a big no-no among the highly evolved vegetarians on Mars. At the sound of the first gunshot on Mars for a thousand years, the Martians naturally grab Avanti and his comrades, who panic, and one of them decides that throwing a hand grenade into the crowd will surely improve their standings. Not so much, as one of the Martians is seriously injured, and the Earthlings are taken to The House of Judgement. Sidenote: the injured Martian, (who survives, we see later) is played by Swedish heartthrob Nils Asther, who would go on to become a major Hollywood star in the twenties.

Once at this solemn House, the wise Martian’s daughter Marya (Lilly Jacobsson) feels compassion for the barbarian men, and wants to act as their counsellor. In a pretty impressive special effects shot, she shows them a movie scene on a big screen TV, that tells the story of how the Martians were once barbaric too, but have later come to their senses and are now pacifists. It seems that the House of Judgement is basically a Catholic confession box, and one only has to repent and change one’s way to be cleared of all charges. This is enough for the Earthlings, who immediately see their own folly and renounce their warlike ways.

A great feast is naturally thrown – and what would a feast be without The Dance of Chastity? This dance is inter-cut with clips from Earth, where partying hordes indulge in wine, violence and vulgarities, starkly contrasting the moral superiority of Mars. And while watching The Dance of Chastity, Avanti is stricken by Marya’s beauty and confesses his love for her. But, hold on to your hats; there is a waiting period for these kinds of things, Marya informs him. First he must sleep by The Tree of Longing – and if she fills his dreams, she will be his forever. Naturally, Avantis dreams are filled with the image of Marya, which seals the deal. She then meets him in The Forest of Love, with a smoking altar and glowing flowers, where they kiss and embrace in a wonderfully sweet scene, with some not so chaste boob … well not grabbing, but gentle patting.

Back on Earth all is not as well. Professor Planetaros and his daughter Corona (Zanny Petersen) are beside themselves with fear and worry, and are not at all helped by Professor Dubius gloating over the press, who are calling the expedition to Mars the greatest failure of scientific history. Rather than live with the knowledge that he sent his own son to his death, Professor Planetaros prepares to drink poison. But right at that moment, word comes by news leaflet (the WhatsApp of the day) that flickering lights have been seen on Mars! Charging to the telescope, the professor and Corona make out seven lights forming the symbol of the big dipper – known in scientific terms as – Corona! Yes, indeed, Dr Krafft has signalled to his beloved fiancée that he is alive and well!

Here’s one for the movie buffs: The telescope and observatory in the Professor’s study are actually the same ones that were used for The End of the Word a little over a year earlier.

The explorers are by now homesick, and the adventurous Marya decides to tag along to Earth – a very good decision, her father agrees, as she can then spread the philosophy of peace among the barbarians. Anyway, he was getting ready to die as it was. Our heroes are then hurried back to Earth with the aid of some super fuel provided by the Martians, and Professor Planetaros greets his new daughter-in-law: ”In you I greet the new generation – the flower of a superior civilization, the seed of which shall be replanted in our earth, so that the ideals of love may grow strong and rich!”

Some none-Scandinavian reviewers have been amused by the end credit proclaiming SLUT – the Danish word for END. Almost as funny as the airport trains in Stockholm telling us when we have reached the Slutstation.

Forget science and logic in this film – it makes no sense. Rather, the movie is a metaphor for a new hope and a philosophy of a better world when WWI was still raging in Europe, and as such the film wins over the viewer’s heart in all its endearingness. It is clear this film was not cheap, and the money shows in the impressive Martian sets and costumes. It is by and large very well filmed, with some quite stunning poetic imagery, especially during the romantic scenes in the Forest of Love. Avanti sleeping by The Tree of Longing could have been shot by Ingmar Bergman himself, and the surreal Forest of Love, with its mystical altar and great, white, glowing flowers has a distinctly Fritz Lang-ish feel. As a matter of fact, one can’t help but wonder if Bergman wasn’t a fan of old Danish cinema, since both this film and Verdens Undergang contain shots which seem to have been directly lifted into The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet, 1957).

The Martian utopia could have used more images like this to spice things up, since a good deal of momentum is lost after the heroes pass the test at The House of Judgement. There is a reason as to why there was a snake in paradise, as the Bible would have been a pretty lame book without it: Adam and Eve would have lived happily ever after, doing The Dance of Chastity. End of story. This is why utopias on film almost always have a snake, or have one introduced from the outside. Peaceful co-existence simply doesn’t make for good drama, and in this case it means that the film stalls a bit in the middle.

However, A Trip to Mars was a great success in its day, with critics and audiences alike. Upon its US press screening, Variety called it “a dignified, impressive, consistent propaganda spectacle, preaching peace and a better world on this earth. It breathes purity, and the story is told reverentially, romantically and with a suspensive spirit of adventure that possesses appeal. It is very carefully thought out and splendidly produced. The direction, acting and photography will stand the test of the best that America has to offer.” The paper praised the main players, and suggested the film “could be boomed in America as a big special”.

The film was something of a great white whale for many decades, as it was thought to be lost. But in 2006 the Danish Film Institute found a nearly complete copy, which was then beautifully restored. As mentioned earlier, this was the first time in cinema that space travel and alien encounters were depicted in a serious movie. It is easy to laugh at the ridiculous space craft, but one should also remember that the great H.G. Wells in his 1936 film Things to Come (review)– that strived for scientific accuracy – still sent rockets into space by means of cannon.

The title Himmelskibet actually means Sky Ship, Heaven Ship, or more poetically, Ship to Heaven. For many years the international title was also Heaven Ship, a name that retains the dualism of the Danish title. For some reason, though, both IMDb and Wikipedia now list the international title as A Trip to Mars, and therefore, so do I. It is certainly an accurate title, and goes well with Jules Verne-ish sci-fi trips to the moon and centre of the Earth and so forth.

Some not so well informed sources claim that the script was based on Danish poet and author Sophus Michaëlis’ novel. In fact, Michaëlis wrote the script along with one of the founders of Nordisk Film, Ole Olsen. Three years later he released a novel with the same name, loosely based on the film. The script is an interesting amalgamations of genres, but has its roots in the classic moral story, and like The End of the World, the theme is highly Biblical. But while the god of the earlier films is the fire-and-brimstone type of the Old Testament, the later carries Jesus’ message of redemption and forgiveness. There’s also a strong influence of Northern European fairy-tales and folklore, especially in the scenes with the enchanted forest, where Marya appears like a fairy of the woods.

As to the science fiction elements, the story draws its lineage from the extraordinary voyages, with a straight line all the way to Lucian’s True History, written in the 1st century, and carried on in the utopian stories of Thomas More and Jonathan Swift. 17th century writers Francis Godwin and Cyrano de Bergerac both described utopian societies on the moon, and utopias were common in proto-sci-fi writings of the 18th century. Sophus Michaëlis’ description of the pious, pacifist society on Mars gives the film a certain kinship with Francis Bacon’s 1627 novel New Atlantis, even if Bacon places his paradise in the Atlantic and not on a distant planet.

The pacifist message of the film was a direct comment on WWI, but because of Danish laws, the films of this little neutral country were not allowed actually make comments on the war, which means it had to be done by means of allegory. Filming began in mid-1917, and the movie was a direct commission by Nordisk Film’s founder Ole Olsen, whoe tasked Michaëlis with writing a film that would be openly anti-war without actually being anti-war.

As for the sci-fi elements, the buildup to the trip to the moon is pure Georges Méliès, although filmed in a realistic style: from the crowded meetings of the scientists discussing the plans of the trip and the infographics used to explain the science, to the one doubting Thomas who gets to eat his words in the end of the film and the obligatory scenes of the building of the space ship. I a sense, this is Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902, review) brought to a feature film setting. Even the propeller-driven bi-plane moon dirigible looks just like something dreamed up by the French pioneer in one of his movies. The second part of the film, on the other hand, closer resembles the biblical epics that were so popular during the first decade of motion pictures.

Director Holger-Madsen was one of the most prominent film makers in Denmark during the golden age of Danish cinema, alongside directors like August Blom and Benjamin Christensen. Holger-Madsen (born Holger Madsen) became a renowned stage actor in the late 19th century, and directed his first film in 1912. An idealist who often laboured with religious themes, he is probably best known for a string of pacifist films during WWI. Apart from A Trip to Mars, one can mention Down with Weapons (1915) and Pax Æterna. A visual innovator, Holger-Madsen often made use of unusual camera angles and surprising lighting, becoming noted for hos side-lighting techniques and his contrasts between dark and light, and he can thus be counted among the inspirations behind German Expressionism. He made around a dozen films in Germany in the twenties, but returned to Denmark with the advent of talking pictures. He only made three talkies, before he retired from filmmaking as a cinema manager.

A Trip to Mars certainly showcases Holger-Madsen’s unique eye for lighting, as he carefully controls the mood and and tone of each scene through the placement of his light source. On Mars he creates stunning visuals that are the result of incredible patience, for example catching the last rays of the sun glittering on a lake behind the characters, just as it is obscured by a small cloud preventing it from blowing out the background. Or just watch the poetic scene from The Forest of Love, where production designer Carlo Jacobsen and art director Axel Bruun have created a whole forest’s worth of white flowers with lights inside them, in the middle of which stands an illuminated altar with smoke rising from it, where Avanti and Marya declare their love for each other. Axel Bruun also worked as art director on the previous Danish sci-fi film The End of the World, where he showed his talent for miniature work. The movie also showcases use of black-screen matte photography, a technique that had been around since the birth of film, but which was uses less frequently as the focus shifted from the sheer spectacle of moving images to story-telling.

One of the most impressive features of the movie is the production design. As stated, the observatory was a re-used set from The End of the World. It is quite possible that the Martian architecture used in the movie were left-overs from some previous historic drama made by Nordisk. Nevertheless, the the sight of ancient Greek-looking archiecture standing on the grassy, rolling hills of Denmark, surrounded by Nordic pine forests, does give Mars a strangely alien feel.

It’s easy to laugh at the absurd look of the space ship, but kudos to the fact that it was actually built as a functioning prop on wheels in full size. And if the outside of the Exelcior is rather goofy, the inside is actually quite impressive, as far as early spaceship design goes. Sure, it’s not much better than some of the stuff seen in bad B-movies from the fifties, but in many ways the Exelcior was the ship that set the standard. This was the first film that actually showed the inside of a spaceship, so there wasn’t any preconceived models to fall back on. What we get is something that is more designed as a ship or a submarine than the rockets of later films, with people moving about horizontally rather than vertically. We’re not told how the ship is propelled, but one can imagine that it works through electricity, as did so many things in the films of the 1910’s. The design isn’t very inventive, we basically get a couple of rooms based on the idea of a submarine, with levers, wheels and gauges, it is nonetheless the first of its kind, and not by a long shot the worst of its kind.

A Trip to Mars also one of the very few films before 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to portray the tedious business of space travel, and the claustrophobic stress of being locked up in a tin can in the vastness of space for months on end.

The nature of outer space was fairly well known by 1918, for example the fact that there was no gravity in outer space. A Trip to Mars, however, omits this fact, and our travelers remain firmly on the deck of the spaceship for the whole trip – or perhaps they have some unmentioned device creating artificial gravity. As with so many later space flight films, this one doesn’t make any special allowances for wining and dining in space either. Our space travellers eat what seems like food prepared on-site from regular china and drink water from glasses, they even put a white table cloth on their table. Apparently drinking alcohol is prohibeted aboard the Exelcior, but that doesn’t prevent them for having a seemingly endless supply of beer and wine on the ship.

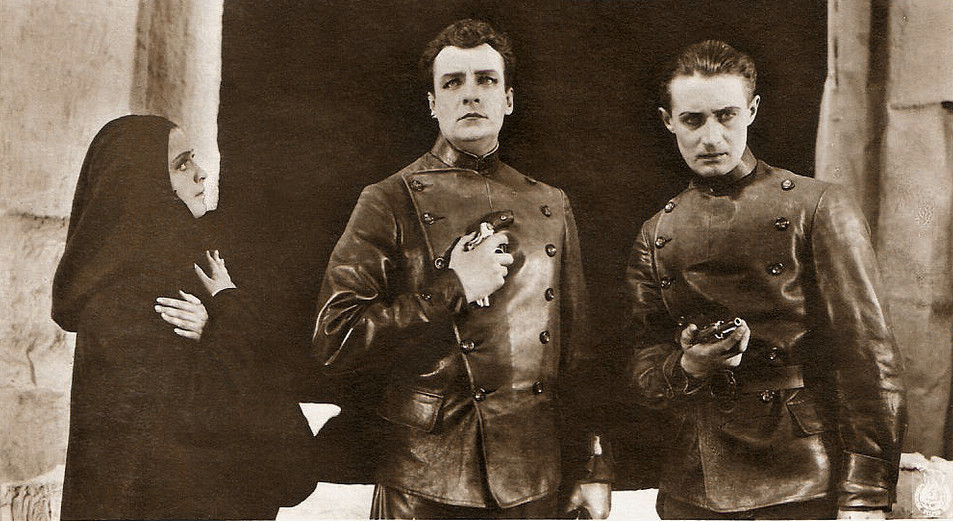

The astronauts don’t have actual space suits, instead they are equipped with the most stylish aviator suits (pants+coat) in leather you will ever see in a science fiction film. The film makes a nod towards realism by having them put on oxygen masks when landing on Mars. But instead of using the mask like a regular person, one of the dimwit astronauts instead decided to open the hatch in mid-landing, take off his mask and test the potentially deadly atmosphere for himself, thus creating yet another long-lasting sci-fi trope: Is the atmosphere filled with lethal fumes? When in doubt: take off your mask and find out, thus sparing the screenwriter a headache.

While the Martian garbs, reminiscent of either Roman togas or Catholic papal robes, are passable, if a bit unimaginative. The women wear sheer white dresses reminiscent of long night-gowns. The idea of the clothing, of course, is to give the Martians a sense of virginity and innocence. However, I would strongly have suggested the omission of the little bonnet worn by the Martian elders, which make them look as if they are cosplaying as babies and will elicit an outburst of genuine mirth when they are first seen by any modern viewer.

The acting in this film is so broad that you could drive two Volvo trucks and Jean-Claude van Damme doing the splits through it. As stated above, Gunnar Tolnæs does a great job pointing at things things throughout the movie, be it his fellow actors, heaven, Mars, a door, a window, a gun, a bottle, the future, god, peace, love, or a number of other things. This does create a good deal of unintentional comedy for a modern viewer, but then again, this film wasn’t meant to depict a realistic story. It is a sort of modern passion play, or a Greek drama. But it does make it difficult to rate the actors’ job.

Interesting faces in the cast include Norwegian hunk Gunnar Tolnæs in the lead, one of the big stars of Nordisk at the time. Tolnæs was a trained actor with an extensive stage background in Oslo, and made films for pioneers like Swedish Victor Sjöström and Finnish Mauritz Stiller (the only Finn with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame) before relocating to Denmark, where he became especially known for his numerous roles as maharajahs in drama films. After he had made a small fortune, he retired in 1929, saying he was tired of making ”sheik films” – although the death of the silent film might also have had something to do with his decision.

Lilly Jacobson (as Marya) was a Swedish actor who was one of nearly 6 000 contestants when Nordisk were choosing a new diva. She won the contest and debuted for Nordisk in 1917 in the hugely successful Maharadjahens Yndlingshustru (The Maharajah’s Favourite Wife), naturally with Gunnar Tolnæs in the lead. She later reprised the role in a sequel. She was one of the most popular actresses of Nordisk until she retired after her marriage in 1919, only once again taking to the big screen as Ophelia in the much talked about rendition of Hamlet (1921), with featured a female Hamlet, played by Danish superstar Asta Nielsen.

In the bit part as the injured Martian we have one of the big stars of Hollywood in the silent era: Swedish heart-breaker Nils Asther, who would go on to play leading men in a string of films opposite Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Barbara Stanwyck and Pola Negri. Most notable are perhaps The Cardboard Lover (1928), Our Dancing Daughters (1928), Wild Orchids (1929), The Single Standard (1929) and Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933). He was a controversial figure, described as self-centred, difficult and self-destructive. It was a well known secret in Hollywood that he was bisexual, which put strains on his US career after the 1930 Hays Code, that prohibited any allusion to homosexuality in film. His accent also made it hard for him to get big roles after the advent of talkies, but he was however fairly successful until becoming blacklisted in 1934.

He is maybe best known for his role as the Chinese warlord Yen in The Bitter Tea of General Yen. Capra thought it was one of his best films, but it was controversial at the time because of its depiction of interracial love. Asther moved to Britain after being blacklisted, but returned to the States in 1938. His career unfortunately took a steady decline and he ended his second Hollywood stint as a truck driver, and moved back to Sweden, where he apperad sporadically in films. Despite his later bad luck in Hollywood, he does have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Another curiosity involves actor Birger von Cotta-Schønberg, who had a bit part in the film. He is most famous for being sentenced to 3 years in jail in 1947 for his aid to the Nazis in WWII. Alf Blütecher as Professor Krafft also showed up in the hugely successful German sci-fi horror melodrama Homunculus (1916, review).

As a science fiction space opera, this film certainly has its share of flaws. But the naive idealism of it all, combined with the sincerity of the actors and the beautiful imagery makes for a very likeable and endearing film.

Janne Wass

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet). 1918, Denmark. Director: Holger-Madsen. Writers: Sophus Michaëlis, Ole Olsen. Starring: Gunnar Tolnæs, Alf Blütecher, Lilly Jacobsson, Nils Asther, Zanny Petersen, Nicolai Neiiendam, Svend Kornbeck, Philip Bech, Frederik Jacobsen. Cinematography: Frederik Fuglsang, Loius Larsen. Art Direction: Axel Bruun. Production Design: Carlo Jacobsen.Produced by Ole Olsen for Nordisk Films Kompagni.

Leave a comment