This 1929 movie is the grandfather of the modern space rocket movie. You name a trope, Frau im Mond created it. Fritz Lang’s German silent film is one of his sillier entries, and has a reputation for being over-long and sluggish during its first half. But if you like Lang’s spy yarns, the build-up is pure cinematic delight — and when the actual space voyage gets underway, it is as riveting today as it was 90 years ago. Thanks to the help of the world’s leading rocket scientists, the scientific accuracy is eerily prophetic. 9/10

Woman in the Moon (Frau im Mond, 1929). Directed by Fritz Lang. Written by Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou, Hermann Oberth. Starring: Willy Fritsch, Gerda Maurus, Fritz Rasp, Gustav von Wangheim, Klaus Pohl, Gustl Gstettenbaur. Produced by Fritz Lang. IMDb score: 7.4 Tomatometer: 71 %. Metascore: N/A.

Frau im Mond (1929) has a bit of a patchy reputation – some regard it as one of Austrian cinema legend Fritz Lang’s masterpieces, others see it as a short bit of sci-fi excitement sandwiched between over-long schmaltzy melodrama. I am inclined to agree with the first assessment, but I can certainly understand the latter. However you look at it, no-one can deny the impact it had on latter moon launch films, nor the film’s visionary scientific accuracy.

Frau im Mond, or Woman in the Moon, sometimes referred to as Girl in the Moon or By Rocket to the Moon was made two years after Austrian demon director Fritz Lang had made his genre-defining sci-fi epic Metropolis (1927, review). Originally the script for that film had an ending which saw the protagonist flying to the stars, but that was scrapped and reworked by his wife and collaborator Thea von Harbou into yet another novel to be put on the screen, just as with Metropolis. Lang himself was extremely interested in space and space technology, as well as science fiction, and was convinced that the technology to make a trip to the moon was within reach in the coming few years. In theory he actually got most of the science and technology right in his film, in large part thanks to technical advisor Hermann Oberth, the father of German rocketry and mentor of Dr. Werner von Braun, creator of the V-2 ballistic missile and later head of the Saturn rocket program. As technical adviser Lang hired Willy Ley, later one of the architects of the American space program.

Watching the film today, it’s perhaps difficult to grasp just how novel it was in 1929. That’s because we forget that this isn’t just an old moon landing film, it’s the original moon landing film. Sure, there had been films involving space trips and moon landings, but most of them were very vague on the subject of how these voyages would work practically and scientifically, and portrayed the moon and the planets in a fantastic rather than realistic manner. The first moon landing movie was Georges Méliès legendary A Trip to the Moon (1902, review) and the second one was the British 1919 film First Men in the Moon (sadly a lost film). The first was a burlesque fantasy loosely based on Jules Verne’s A Voyage to the Moon, with elements of H.G. Wells’ First Men in the Moon. It spawned quite a little industry of mimicry after it came out. The second was more or less completely based on Wells – but this was also complete fantasy. Verne had his rocket shot out of a cannon and Wells invented the gravity-defying alloy Cavorite.

Lang would also have been inspired by the Danish 1918 film A Trip to Mars (review), a pacifist yarn about a team of explorers flying a space dirigible to the red planet, finding there a peace-loving and vegan society of Greek-styled philosophers. What would have appealed to Lang in this film was the surprisingly realistic way in which it described the long and tedious journey to Mars, with a group of men stuck together in a tin can for six months, with little chance for recreation and no guarantee of a successful mission. Another famous early space film was the Soviet social satire Aelita, Queen of Mars (1924, review). However, that film had a bigger influence on his Metropolis than on Woman in the Moon, as the actual time it spends on space flight is very limited, and we only see Mars as a futuristic dystopian city, rather than as an alien planet. It does have a weightlessness scene that may have inspired Woman in the Moon, though. But the greatest cinematic influence on Woman in the Moon probably came from a German educational film released in 1925 called Our Heavenly Bodies (review). A marvel of stop-motion animation, this film took the viewer to the moon and the planets in our solar system, scientifically explaining the basics of astronomy, as well as speculating on the possibility of life on the different extraterrestrial bodies, and what it might look like if it existed. It also gave a scientific explanation of the mechanics of space travel from the point of view of the theory of relativity, faster than light travel, etc. What it didn’t do though, was explain anything about how an actual space ship might work. And that’s where Lang thought he could do better. In fact, he hoped that his film would help along the real-world efforts of actually sending a manned rocket to the moon.

No-one had ever described space travel or moon landings with such a realistic and detailed approach in fiction before. Most people simply didn’t have the money to hire a bunch of rocket scientists and astronomers to aid them. It wasn’t until 1951 and producer George Pal’s expensive space film Destination Moon (review) that any Western filmmaker attempted anything similar. The Soviet Union did, however, produce a fairly accurate moon saga Cosmic Voyage in 1936 (review).

Fritz Lang wasn’t known for making films that were short and to the point. His 1924 epic Die Nibelungen was nearly five hours long, his best known film, Metropolis, nearly three hours, and Frau im Mond clocks in at over 150 minutes. It is roughly divided in two parts: one involves a spy drama on Earth, the other the actual space flight and hunting for gold on the moon. It takes a whole 73 minutes before we get to see the moon rocket, and some critics have found the build-up slow going. I, for one, do not.

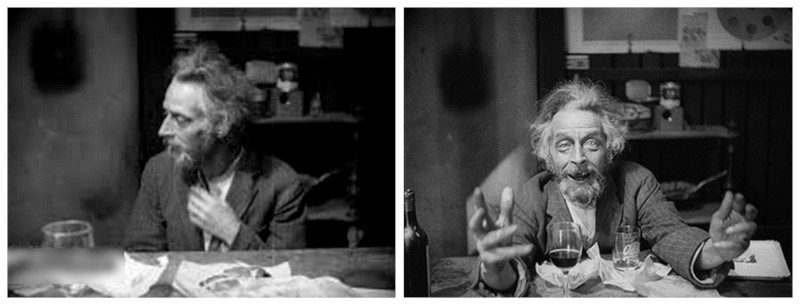

The film starts with Helius (Willy Fritsch), a successful young flight engineer who seeks out his old mentor and friend Professor Mannfeldt, wonderfully played by a spirited Klaus Pohl. Decades ago Mannfeldt presented his theory that on the dark side of the moon there was a breathable atmosphere, and more importantly, that the mountains of the moon were filled with gold. Laughed out of the scientific community, he now lives in a small attic with no-one but a house mouse to keep him company, and the occasional visit from Helius. The first scene between the men sets the tone for the film – and is filmed with such ingenuity, attention to detail, humour and numerous small quirks that immediately presents far more about the characters and their relation than what is said in the title cards – that it is hard to understand how people find all of this boring. The film opens with a bang – a furious Mannfeldt kicks an intruder down a flight of stairs. The tall, well-dressed man flails as he lands straight in the arms of a surprised Helius. Leaned double over the railing is the infuriated Professor, shouting and ranting: ”Let that leech break his neck, Helius! Here I have been living like a dog because of my ideas for thirty years, and now this trickster wants to profit from my misfortune – and buy my manuscript as a curiosity!” the intertitles tell us – in German, in the copy I have seen. After calming the Professor, Helius finds a calling card the trickster has left behind – ”Walt Turner, Chicago” is all it says.

The following scene is a beauty to watch in all its simplicity. The small run-down attic cubicle in which Mannfeldt lives tells a whole life’s story. As Helius unwraps a beer and a chicken dinner for himself we get sort of throwaway shots of accolades hung on the walls, that are covered in scribbled numbers and parables, there’s a desk and a telescope by the window. Lang takes joy in showing us details like Mannfeldt removing a stack off books from under a chair, where they serve as support in the absence of a leg, stacking them on the chair, dragging it to the small table for Helius to sit on, and slam the chair down as Helius asks for a loaf of bread to go with his dinner, after having painstakingly brushed the floor dust from his stylish, but badly worn dress. Next Mannfeldt slams a banknote on the table – ”I found this in my coat pocket after you were here last – buy bread with that, Herr Helius. Please spare me the disgrace of receiving alms from my only friend …”

Out of pride he refuses to even share a sandwich with Helius, as he himself sits on a potato box when Helius gets the big chair. To emphasise the different worlds of the two friends Lang even splits the screen with a wooden column right down the middle, with the wealthy, young Helius and his dinner one side, and the hungry and unkempt, but proud, Mannfeldt on the other. Of course when the whole scene is over, Helius ”forgets” to eat his dinner, and it gets eaten by Mannfeldt and his mouse – which is of course what Helius intended all along. Anyway, during this awkward dinner is when Helius tells Mannfeldt that he has decided to build a rocket to the moon to put Mannfeldt’s theory to the test – and naturally the good Professor is overjoyed, and insists on coming along. During the conversation we also get to know that Helius’ best friend and colleague Windegger (Gustav von Wangheim) will not be going along. He is about to marry Helius’ other assistant Friede (Gerda Maurus), who Helius is also secretly in love with. ”He won’t have time for the trip”, Helius bitterly says.

This scene just takes up ten minutes, but the sheer wealth of information we get in the scene, that never once feels like an exposition scene, is staggering. In fact, it is filled with humour, excitement, humanity and warmth, it sets up the plot, gives us an extensive portrait of two of the film’s main characters and introduces two more (actually three, if you count Turner). All this over a small chicken dinner, that is all filmed with the same passion and style as if it were the moon flight itself on screen. Such is the genius of Fritz Lang.

The plot itself really is not of much consequence. The next 60 minutes have two basic threads: Windegger and Friede convincing Helius that they are to come along on the trip, and Turner and his conglomerate of evil capitalists stealing the manuscript and blackmailing Helius to let Turner tag along for the ride. But is so beautifully filmed, with all the little quirks and details and humour laid out as candy before the viewer. Maurus plays a surprisingly strong female – something sadly absent from the sci-fi genre for many decades to come. She doesn’t move around the spaceship serving the men tea, as in many later films, but actually does scientific work (actually she seems to be the only one doing any scientific work as the team lands on the moon). Maurus plays her character with a great calm and seriousness, and although she is a joy to behold she is fortunately never reduced to eye-candy. Fritz Rasp, who we saw earlier as the evil henchman The Thin Man in Metropolis, relishes the role as the oily, devious ”the man who calls himself Walter Turner”, as the credits introduce him.

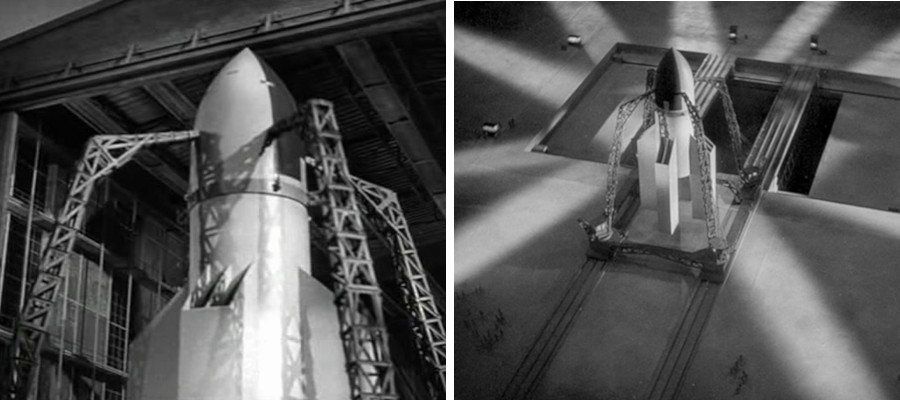

Halfway into the film comes the moment the audience has been waiting for: the takeoff toward the moon. With the help of Hermann Oberth and his other scientific advisers, Lang presents, for the first time on film, a scientifically feasible moon rocket. The rocket used is a three-stage liquid fuel rocket, just like the ones used for real in later space missions. The whole takeoff scenario is eerily reminiscent of moon flights taking place 40 years later. First the building of the rocket in a gigantic hangar, and then rolling it out on a huge gantry on tracks, exactly like NASA did. There’s a beautiful aerial shot of the takeoff area, a very realistic miniature, and it’s like your looking at Cape Kennedy. Lang also foresaw the massive public interest with a live audience, worldwide media coverage and even a Walter Cronkite-like announcer. The unveiling of the rocket is an impressive sequence – an wide shot showing the outline of the craft slowly advancing from the hangar in the middle of the night, with searchlights waving to and fro, giving it all a very expressionist touch. The people in the foreground are clearly static miniature models, giving away the scene. The whole sequence is nearly ten minutes long, and this is the only place in the film where I’d actually have cut it shorter.

Before the takeoff Helius begs Friede to stay behind and she scalds him for thinking of her as a woman first and an important scientist second. From a feminist point of view this is rather progressive for a thirties film. Friede is also clad in coarse trousers, a masculine shirt, a man’s tie and a waistcoat, as if to further point out that she is equal to the men, and all skills and no frills. (Although the universal gear of a knitted woollen sweater over shirt and tie does seem a rather impractical set of wardrobe for a lunar mission.)

The takeoff is preceded by a sequence that now seems so integrated to space travel that we take it for granted: the 3-2-1-takeoff countdown. The thing is: Fritz Lang invented it. More on this later. Suffice to say, Lang wanted utmost realism in describing the space flight. The passengers are strapped down for the G-forces of takeoff (lying and not sitting), two bicycle wheels serve as a gyrometer and the difficulty of manoeuvring and dumping the boosters under G-force distress is well presented. Weightlessness in space was an accepted theory at the time, and had even been portrayed on film at least twice: both in Aelita in 1924 and in Our Heavenly Bodies in in 1925. Of course free-floating is a concept that give filmmakers headaches even today, and back in 1929 it was ten times more difficult to portray it. Woman in the Moon mostly circumnavigate the problem by having all the floors covered with straps to stick your toes under when you walk. In later movies the straps were often replaced by magnetic boots. Stanley Kubrick opted for velcro in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). But Lang put in one scene of actual floating in order to fix the idea in the audience’s mind. There is a pretty impressive shot of the stowaway boy Gustav shooting up through a manhole and hitting his head on the ceiling. If you stop the frame you can clearly see the wire, but it is such a quick sequence and the wire is cleverly placed close to the metal ladder, so it’s practically invisible if you don’t know where to look.

Lang might also be the first director to include the later seemingly mandatory scene where crew members drink alcohol bubbles in weightlessness. The bubbles are pretty crudely animated by today’s standards, and it’s the only special effect that really seems dated today. The booze cabinet is one of the less realistic features on the spacecraft, but one that, oddly enough, seems to turn up in almost every space flight film from 1929 through to the fifties. But at least Woman in the Moon doesn’t have a china tea pot on board the rocket, like Cosmic Voyage.

Oh, the stowaway? I have left out one of the main characters, namely the young boy Gustav (Gustl Gstettenbaur), sort of a protégé of Helius, who aids him in trying to catch one of the spies and has no higher passion in life than reading sci-fi pulp magazines. Of course he isn’t gonna get left behind when Helius goes to the moon. In a way one can see him as Fritz Lang’s alter ego in the film. Lang was not only obsessed with space flight, but also loved science fiction magazines. He had a huge collection of old magazines, that were all donated to a museum after his death.

On the moon all science disappear and Lang digs up his love for pulp stories. Prof. Mannfeldt does go out on the surface in a space suit that looks more like a deep-sea diving suit. Then he tests the atmosphere and decides it is breathable (by lighting a match) – and dashes off to the mountains with respectable speed for his age. In a cave he passes a bubbling pond of mud and – lo and behold – finds the mountains are stuffed with the precious metal. But, alas, as the story often goes, greed makes you blind, and the good professor meets the end of his days at the bottom of a pit, laden with enormous chunks of gold. Of course, well on the moon and now with the prospect of endless riches, the story comes to a dramatic point, and Lang introduces yet another first on film: the old “there’s not oxygen/fuel enough on the ship for all of us to get home” — hence the film’s title.

Woman in the Moon has been described as one of Lang’s ”lesser” films, and in a way it is. But just to the extent that Much Ado about Nothing is one of Shakespeare’s lesser plays. A Lang film is always a Lang film. It is true that it lacks the gravitas of Dr. Mabuse, the epic quality of Die Nibelungen, the visual impact of Metropolis and the cinematic experimentation of M. But this film shows the other side of Lang, the playful Lang that relishes in the telling of small stories within the big picture, the Lang that loved entertaining spy novels and pulp magazines. This is the side he had earlier showcased in Die Spinnen and the visual fury of Spione – the ultimate spy film of the mid-twenties. He clearly had tons of fun while directing this – where he could have his actors do silly things completely unrelated to the plot. We have Professor Mannfeldt with his pet mouse Josephine that he insists on taking with him to the moon, Gustav and his pulp fiction, and a hilarious scene when Helius is using his neighbour’s phone, and we see him absent-mindedly fiddling with something off-screen. It turns out he has been using a pair of scissors to maul his neighbour’s potted plant. The film is crammed with these little details, making it a joy to watch.

However, the circumstances of the film weren’t necessarily joyous. Fritz Lang’s previous film, the megalomanic Metropolis, had flopped at the box office and all but ruined the national film company Ufa. The company now demanded Lang make amends. Sound film was the new thing, and Ufa would have wanted their top director to make a talking picture. But Lang despised this novelty, and insisted on making Woman in the Moon silent. And as opposed to his work on Metropolis, this time he had actual budget restraints. Which he happily flaunted. For example when he ordered 40 truckloads of sand to be brought into the studio and be roasted in order to create the right look for the moon.

A film like Woman in the Moon could not have been done even six years earlier. In 1923 there had been no Aelita, no Our Heavenly Bodies and no Metropolis. Sure, there was talk of going into space, but this was generally considered as highly theoretical talk between scientists, or science fiction fairy tales. Despite he growing public interest in science fiction, producers had no way to determine just how successful a space film would be. Wells and Verne were fairly popular in Germany, but not quite bestsellers. And besides, Verne had been dead for 20 years, and Wells’ most popular books were written in the late 19th or very early 20th century, again, over 20 years ago.

But things were different in 1927, when work began on Woman in the Moon. Aelita and especially Our Heavenly Bodies had proven that a space film could make very good business in Germany. While its story was considered to be too complex and garbled, Metropolis had shown studios just what could be done visually and thematically with the medium of film. Furthermore, the concept of actually visiting the moon and other planets were slowly beginning to be taken seriously in academic circles. One very important step was that in 1926 American Robert Goddard had been able to successfully use liquid fuel as a propellant for a rocket. And there was much talk of space, as new discoveries were being made: In 1927 Georges Lemaitre first proposed the idea of a Big Bang, and two years later Edwin Hubble all but confirmed the theory by proving that the universe was expanding. There was also a new generation of both scientists and culture personalities that had grown up on science fiction, like the stories of Wells, Verne and Edgar Rice Burroughs. Fritz Lang was an avid reader of sci-fi, as was Hermann Oberth, who was inspired to start studying rocketry thanks to the books of Verne and Wells. Later he also discovered the writings of Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the father of rocket science, who also wrote popularised science books and even science fiction about life on other planets and especially on space flight and the colonisation of space in the early years of the 20th century.

In 1922, the 27-year old Austro-Hungarian teacher Hermann Oberth’s doctoral thesis on using rockets for space flight was rejected by the University of Göttingen for being too “utopian”. Seeing as German academia wasn’t far-sighted enough to accept his ideas, he abandoned the thought of writing another thesis, and instead published his thesis privately in 1923, as Die Rakete zu den Planetenräume (“Rocket into Planetary Space”) — and to the surprise of everyone it became a bestselling book. He did, however, receive a doctorate from a university in Romania with the same thesis he submitted to Göttingen. Oberth’s book inspired a young generation of scientists and dreamers, who all made it their cause to promote space flight. Among those who read Die Rakete zu den Planetenräume was a 19-year old science student named Willy Ley, who sat down and wrote a popularised version of its theoretical content, and after two years’ correspondence with Oberth and other rocket scientists in Germany, published the popular scientific book Die Fahrts in Weltall (“Travels in Space”) in 1926. Another one was Max Valier, a physics student and machinist, who also contacted Oberth, and with his help published another book, Der Vorstoss ins den Weltenraum (“The Advance into Space”) in 1924. Valier soon began working with Fritz von Opel (the car manufacturer) on rocket-powered drag-racing cars. The best known of Oberth’s disciples is probably Wernher von Braun, who helped develop the US space program. In 1924 he was only 12 years old, but was so inspired by the drag-racing stunts of Opel and Valier, that he caused a disruption in a crowded street by accidentally blowing up a wagon with fireworks attached to it, and was taken into custody by the police.

Oberth, Ley and Valier were all called upon by Fritz Lang in 1927 to act as consultants on his film. As a publicity stunt Ufa wanted to launch a liquid fuel rocket prior to the opening night of Woman in the Moon, which meant that for over a year the film company funded Oberth’s research and the development of the rocket, with Ley and Valier as assistants. For the purpose of the work, and the broader task of sending men into space, they created the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (“The Society for Space Ship Travel”) in 1927 — the first organisation specifically devoted to space travel, and a precursor to the US and the Soviet space programs. von Braun joined the society in 1930. Oberth couldn’t get his rocket to work in time for the opening night, but the work done for the film served him well when he in 1941, along with Wernher von Braun, unveiled the V-2 rocket for the Nazis. In 1929 Oberth also expanded on his thesis, and wrote a tome of over 400 pages on space flight. The work of Oberth, Ley, Valier and von Braun, helped in no little amount by Lang, von Harbou, Ufa and Woman in the Moon, created a rocket craze in Germany in the late twenties and early thirties. The Verein für Raumschiffahrt, inspired by the writings of Tsiolkovsky, laid down the groundwork for space rocketry and ballistic missile technology. Valier sadly died in 1930 in a fuel tank explosion, but von Braun and Ley later became architects for the American space program, with von Braun personally responsible for creating the Saturn V rocket that took Neil Armstrong to the moon. Oberth also later joined the US space program. And it was Woman in the Moon that was ultimately responsible for bringing these minds together.

Woman in the Moon has been said to have been “of enormous value in popularising the ideas of rocketry and space exploration”. Case in point: the T minus time launch countdown. Both in reality and in fiction rocket and space ship launches had up to this point been preceded by a count-up (1-2-3-Go, etc), if indeed any numerical counting was even used. Earlier versions of the script also used a count-up. One probable reason for the change was that it made practical sense to do a countdown rather than a count-up. Oberth & Co would have told Lang that launching a rocket to the moon would require precise timing for it to reach its intended trajectory and speed, and thus everything had to be ready at a very specific moment. Counting down would give everyone involved a clear idea of just how much time remained for each step. But it was also a great way to add tension to the movie. Counting down signals the approaching point of no return, and with each lower number the audience grips its seats just a little bit tighter. Now, remember that Lang opted not to use sound in his film. This removed the possibility to add sound effects like roaring engines, blast-off explosion sounds, klaxons howling, alarm bells blaring, etc. Instead, he had to find a visual way to gradually build up the dramatic tension of the launch. So he decided to do it through intertitles and editing, borrowing from French impressionists such as Marcel L’Herbier’s superbly dramatic lab scene in The Inhuman Woman (1924, review) and Soviet montage theorists like Lev Kuleshov and Sergei Eisenstein. The always brilliant Atlas Obscura describes the takeoff scene like this:

“As the astronauts lie in their bunks, eyes wide and jaws tense, the screen cuts to an announcement: “Noch 10 Sekunden-!”—10 seconds remaining! The mission leader grips the firing lever—”Noch 6 Sekunden!” The numbers get bigger, filling the screen: 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, JETZT! Now! The lever lowers, and the rocket blasts out of the water. Nearly a hundred years later, it still gets the heart pumping.”

Considering that Oberth, Ley and von Braun helped shape NASA’s space program and its procedures, an interesting question to ponder is whether Fritz Lang accurately anticipated what the US space program would look like, or if he actually supplied the blueprint for it with Frau im Mond. As CineOutsider puts it: the presentation of the moon flight is so accurate that “you can’t help thinking that a file full of NASA documents from the late 1960s fell through a time warp and landed on Lang’s desk”. Whatever the case, Frau im Mond is without doubt the most influential space flight film of all times, creating the look and dozens of tropes that are still seen in films today. What Lang did for dystopian films with Metropolis, for spy films with Spione and for film noir with M, he did for space flight films with Woman in the Moon.

The moon itself is spectacularly well rendered, and it would take decades until such a well defined outer space world would hit the screen – the 1956 film Forbidden Planet (review) is probably the first one to live up to the standard. Overall the production design for the movie is stunning. Naturally, the resident eggheads helped out with all things rocket-y, but there was also Lang’s go-to art directors Karl Vollbrecht and Otto Hunte, who both also worked on Metropolis, as well as Emil Hasler, who also collaborated frequently with Lang. Artist and illustrator Joseph Danilowatz helped out with the design of all things machine-related, for example the rocket miniatures, ramps, etc and matte paintings of technical subjects. Danilowatz was an artist and magazine illustrator whose interest in industrial subjects led him to become a designer at German model train manufacturer Märklin. More traditional matte paintings were done by Gustav Wolff, a renowned landscape artist who fled to the US during the Nazi rule, and has since had a museum opened in his name.

The film had a total of four cinematographers credited. Konstantin Irmen-Tschet is of some interest to sci-fi fans, as he also worked on Metropolis and all three versions of F.P.1. (1932-1933). Oskar Fischinger later did the animation for Ib Melchior‘s B-movie The Time Travellers (1964). These two were also in charge of the special effects of Woman in the Moon, such as the animation, stop-motion and miniature photography.

There are scientific flaws that people have pointed out. The rocket takes off from a water basin, there is no weightlessness in freefall in the movie, the rocket doesn’t orbit the moon before landing, the rocket itself seems to be steered with two huge levers, etc. But first of all – this was all highly speculative back then. And second – even realistic films like Apollo 13 and Gravity have taken liberties with reality, and this was ultimately a fantasy film.

This was Fritz Lang’s last or second-to-last silent film. He would follow it up with M in 1931, a semi-sound picture, but in many ways filmed like a silent. It’s seen by many as his ultimate masterpiece, and was reportedly the film he liked best himself.

As you may have surmised, I am partial to Woman in the Moon. However, I completely understand some of the arguments made against it, and can understand why it has remained a curio on Lang’s resumé. There’s something of a clash of tones and styles, and one can even see it as three films artificially Frankensteined into one.By the time we get to the moon, the first third of the movie is completely irrelevant. And if you’re in it for the moon action, I can totally understand that the 45-minute Earth-bound prologue can seem endlessly boring. I think it’s partly a question of expectations and being in the right mood. It’s a rather daunting film to sit through at 250 minutes, and not something I do lightly. However, I feel that the first part of the film, while irrelevant for the moon plot, is such beautiful filmmaking that I can just watch it for the sheer joy of watching a master at work. And it does give the characters backstory and motivations, set up the moon voyage and explain in detail how it is scientifically feasible.

The third act is, in fact, the one that I have most difficulty with, because of the drastic change of tone. After having painstakingly followed all scientific rigour in setting up the moon mission, Lang (or, many suspect, primarily Harbou) throw all science out the window. It suddenly reminds me of an episode of Ducktales, Scrooge MacDuck bounding over boulders in hope of finding a mountain of gold inside the moon. Of course, Carl Barks wouldn’t have pretended there was air on the moon, as this film does. Indeed, this feels like Lang paying homage to the pulp stories of his youth, just like little Gustav is a representation of his childhood.

Some reviewers completely fail to see what I see in the in the first half of the movie. Philip Winter a the British Electric Sheep Magazine writes: “The screenplay is porridge through and through, and by George it’s lumpy.” Clayton Dillard at Slant Magazine goes as far as equalling Lang with Michael Bay, writing that they are perhaps “kindred spirits after all, each in pursuit of radically affecting the viewer’s sensorium, but neither able to restrain themselves, or their cinematic egos, when given a blank check.”. And I can certainly agree with Jeremy Carr at PopOptic when he writes that “this is a film far more about spectacle and science than it is a reasonable storyline”.

But I’m not the only one to take delight in the film’s length and build-up. James Wegg Review writes that Thea von Harbou “has crafted a fuller than full-length rendering of this tale of greed”, and continues to say that “the pace is at its best before the voyage”. Fernando F. Croce at CinePassion calls Woman in the Moon “an agoraphobic dream-film, richly attuned to human detail amidst dwarfing machines”. Brian Orndorff at Blue-Ray.com sums up what I think some overly critical reviewers have missed:

“Woman in the Moon doesn’t present a simple space opera, but makes an effort to build a story of discovery and manipulation along the way, with extensive screen time devoted to creating proper motivations before the picture launches into space. […] Woman in the Moon intelligently examines pieces of its puzzle, but it also pays attention to larger acts of intimidation and human connection, with Lang developing personality and dramatic need before the special effects display begins.”

And D.W. Mault at CineVue argues that the film should be rehabilitated as something more than just one of “Lang’s lesser films”: “Frau im Mond is not a masterpiece in and of itself, but its beauty and influence seeps through cinema and culture […] Lang’s inserted adult paranoia of subterranean plotting would be strip-mined by Hollywood for years, while one only has to look at Hergé’s Tintin stories to see another avenue that spun off from Lang’s visionary tumult. Lang referred to himself as ‘an eye man not an ear man’, and never is this more apparent than in Frau im Mond, with its reimagining of the unknown and its telegraphing of the populace’s idealisation of space travel, the moon and adventure. More than anyone, Lang instilled in the consciousness of the world the visionary template for what would come in fact and fiction. We can see the vapour trail from Frau im Mond right through to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), heading straight towards us via a fantasy ride of electronic light and vision.”

Thea von Harbou doesn’t receive much love from Lang aficionados, as she tends to be blamed for most of the flaws in the scripts of his films. Despite this, one cannot deny that the duo of Lang-von Harbou was something of a super-tag team in German cinema. The two met while collaborating on The Walking Shadow in 1920, and together made such masterpieces as The Weary Death, Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler, Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, Woman in the Moon, Spies and M. In between she also worked on projects like the blockbuster adventure films The Indian Tomb, part I (The Mission of the Yogi) and II (The Tiger of Eschnapur) with Joe May (1921) and The Phantom (1922) with F.W. Murnau. The former two were based on her 1918 novel The Indian Tomb, which has become one of her most lasting legacies, prompting three different film adaptations. Richard Eichberg remade the two films as The Indian Tomb and The Tiger of Eschnapur in 1938, and Fritz Lang himself remade them again, with the same titles, in 1959, after his return to Germany from Hollywood.

von Harbou and Lang had an uneasy marriage, as Lang was a well-known womaniser, and apparently neglected all domestic chores. And during the making of Metropolis Lang caught von Harbou in bed with an Indian reporter 14 years her junior, who later became her husband. But their eventual divorce in 1933 also had political flavour. After Metropolis, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels started courting Harbou for a position as a propaganda employee in the party, but Lang would have none of it. There has been much speculation over just how devout a Nazi Thea von Harbou was. What we do know is that she did join the Nazi party, and remained loyal to Germany under Nazi rule, unlike Fritz Lang, who left the country. It is also documented that their differing opinions on nazism was one of the factors contributing to their divorce. While never officially becoming part of the Nazi propaganda machinery à la Leni Riefenstahl or Veit Harlan, she continued to write films during the Nazi rule and WWII. Most of them were not explicitly political, but she did work as a consultant on a number of movies with clear Nazi ideology. After the war she said that the main reason she stayed in Germany was so that she could help Indian immigrants, such as her husband, and that she did not sympathise with the regime, and focused her efforts on doing volunteer work to help war-stricken civilians by welding, making hearing-aids and doing medical work. She received a medal for saving people during an air raid. During the war she also directed two films, but found that she didn’t enjoy the process.

After the war Harbou spent some months in a British prison camp, where she put on a performance of Faust. After her release she worked as a so-called Trümmerfrau, helping to rebuild bombed cities. She returned to screenwriting in 1948, and continued to write up until her death in 1954. While she fared better than many filmmakers who had collaborated with the Nazis, she wasn’t able to recapture the success she had had with Lang. Apart from her work with Lang, her greatest legacy is probably the adventure novel The Indian Tomb, which, as mentioned, was adapted for the screen on three different occasions.

Austrian-born Fritz Lang is one of the true greats not only of German, but international cinema. After establishing the pre-Blofelt world dominating villain with Dr. Mabuse, and revolutionised sci-fi with Metropolis, he made the expressionist spy classic Spies (1928), and created the template for all other moon travel films with Woman in the Moon.

The 1931 expressionist masterpiece, and Lang’s first sound picture, M, is considered one of the greatest films of all time, and a huge influence of the film noir genre. Before fleeing the Nazis to USA, he still had time to make The Testament of Dr. Mabuse in sound in Germany in 1933. He made over 20 films in the States, many of which are today considered highly influential classics, such as Fury (1936), the epic western Western Union (in colour, 1941), the Bertolt Brecht-scripted Hangmen also Die! (Venice film festival winner, 1943), The Woman in the Window (1944), a film that among a few others marked the onslaught of American film noirs, the violent, dark The Big Heat (1953), noted for the brutal disfigurement of star Gloria Grahame, after Lee Marvin’s thug throws scalding coffee in her face, and the geometric, cold noir While the City Sleeps (1956). Few directors have had such a huge influence on so many genres, and had such a productive and creatively successful career over so many decades. The great shame is that he was not always as revered during his American years as he should have been, and that he never won an Oscar, not until 1976, when he got a lifetime achievement award just six months prior to his death.

Woman in the Moon will never be counted among Lang’s greatest films, nor should it. It has its flaws, the biggest of which is probably the daffy last third of the movie. But it’s not just an astounding feat of technological prediction. It is also, very much like his celebrated Metropolis, a movie that had a profound influence on later science fiction films. The movie didn’t initially cause any great surge of space-themed films, in fact the scarcity of space movies in the thirties and forties is a bit surprising. There was a last hurrah for the the sci-fi epic in 1936. That’s the year that the USSR released Cosmic Voyage, a movie based on Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s ideas, but also very much influenced by Woman in the Moon. This was also the year of Alexander Korda’s, William Cameron Menzies’ and H. G. Wells’ wooden futuristic epic Things to Come (review), which features a — oddly enough — a space cannon reminiscent of the one dreamed up by Jules Verne in his novel From the Earth to the Moon (1865). But with the popularity of Frankenstein in 1931 science fiction films instead took a very Earth-bound slant, with mad scientists dreaming up monsters and death rays rather than space ships. With the exception of a couple of oddball comedies, there really wasn’t another space film until the fifties, when Destination Moon (1950) blew open the flood gates. Watching the space flight films from the fifties one is still astonished by how much they are influenced by Woman in the Moon. From the build-up to the space flight, the preparations, the look of the rocket, the design of the interior, and of course the whole takeoff procedure.

And while astoundingly silly in the light of the scientific rigour of the first two acts of the film, the third moon-based act was in fact also very influential, especially on the B-movies of the fifties, but through them also to this very day and age: The lauded film The Martian (2016) is based on the same theme of someone being left behind on a celestial body that Woman in the Moon pioneered, although it was perhaps more inspired by the Robinsonades than anything else. The idea of someone being left behind on the moon or a planet originally comes from H.G. Wells’ 1901 novel First Men in the Moon, however, that character gets left behind because he is captured by selenites. It was Lang and Harbou who pioneered the now oh-so-tired trope of the rocket having too little fuel, oxygen or supplies to carry the whole crew back to Earth. The trope was picked up by the pioneering “big-budget” George Pal movie Destination Moon in 1950, and from there spread like wildfire among the B-movies of the decade, and onward to our days. It’s also the precursor to having all the controls on the ship in very awkward places, so you can’t actually operate the launch from the bunk where you inevitably will be pinned down by the G-forces — another one of those stupid tropes that became staples in fifties B-movies.

As noted earlier, the acting is top-notch in Woman in the Moon. Willy Fritsch as the leading man is not exceptionally memorable, but good, in fact better and more versatile than about 99 percent of all leading men in similar films to come. Fritsch was a very popular leading man in German cinema from 1928 onwards, when he was paired with actress Lillian Harvey. He joined the Nazi party out of convenience, but did his best to stay out of propaganda films (despite popular misconception, other films than propaganda were made during the Nazi rule of Germany), and survived the Nazi period with his reputation fairly intact. He continued acting until 1964, when he started a career as a screenwriter, that lasted to his death in 1973. He had previously appeared in Lang’s film Spione, and had no other outings in sci-fi.

Gerda Maurus as the leading lady has a lot more spunk than almost all space ladies in the decades to come, perhaps partly because of the script being written by a woman. Naturally, the character is coloured by the gender roles of the time, but the astronomy student Friede is a far cry from the fainting daffodils of later science fiction films. Smart, brave and headstrong, and Maurus has the oomph to portray the role. The beautiful blonde Gerda Maurus (born Gertrud Pfiel in Austria, present day Croatia) was a theatre actress who caught the eye of Lang in 1928 and also starred in Spione, after getting the lead in Frau im Mond and Hochferrad (1929, known as High Treason in English, but not to be confused with the British 1929 sci-fi film High Treason (review). Her star diminished somewhat with the talkies, and her career was more or less ruined after WWII because of a brief collaboration with Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels.

The salt of the film is the wonderful Klaus Pohl playing the daffy scientist Mannfeldt — impulsive, emotional, just as prone to outburst of rage as to dancing from happiness, and endearingly attached to his little pet mouse. Pohl is described as ”a spindly Austrian actor, a busy supporting player of the 1930’s and 40’s. He tackled a multitude of diverse roles, some of his best work being for the director Fritz Lang”. Professor Mannfeldt is Pohl’s best remembered role, and he worked (uncredited) on Spione and M for Lang as well. It is odd that he never got bigger shots at acting, as his work in Frau in Mond is superb. In 1934 he appeared in a supporting role in Harry Piel’s sci-fi film Gold, about a mad scientist and his robot army. He was also a respected stage actor.

Fritz Rasp is also absolutely superb as the sinister, anonymous, “villain”. Had the film been done after WWI I’d perhaps accuse Rasp of doing too much of a stereotype Gestapo villain of the type found in Raiders of the Lost Ark, but since the movie was made in 1929 I can only call his performance prophetic. Rasp had a long film career spanning from 1916 to 1976. He is best remembered as The Thin Man in Metropolis, and from his work in The Love of Jeanne Ney (with Metropolis co-star Brigitte Helm, 1927), Woman in the Moon, Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), and The Threepenny Opera (1931). He also starred in Spione and two versions of the Sherlock Holmes story The Hound of Baskervilles (1929 and 1937). Metropolis and Woman in the Moon were his only sci-fi films.

Young Gustl Gstettenbauer had begun his acting career a year earlier in a little known film called Der Piccolo vom Goldenen Löwen, in the role of the piccolo, in 1928, and had a small role in Spione. His acting career took off after Woman in the Moon, and he continued to appear in films and TV until 1976, although he seems to have been banned for a few years after the Nazi regime.

Gustav Wangheim, playing the engineer Windegger (born Ingo Clemens Gustav Adolf Freiherr von Wangenheim), is best known for his role as Thomas Hutter (a renamed Jonathan Harker) in F .W. Murnau’s genre-defining Nosferatu (1922). He was a devoted communist and moved to the Soviet Union when the Nazis came to power. He continued to produce movies and was the head of a German cabaret in Moscow. He was later accused of denouncing two of his colleagues as Trotskyites, leading to one of them being executed. His son has later tried to clear his father’s name by explaining that his colleague was killed because of accusations that he had planned to kill Josef Stalin, and that Wangheim had stubbornly refused to confirm this suspicion, despite a long interrogation with the KGB. He returned to Germany in 1945, working as a stage director and producer. He is played by comedian and actor Eddie Izzard in the 2000 film Shadow of a Vampire, a fictionalised account of the making of Nosferatu.

Woman in the Moon received mixed-to-positive reviews upon its release. It wasn’t quite the astounding success at the box office that Ufa had hoped for, but at least went down better with audiences than Metropolis: it also avoided the severe chop-job when exported that had killed the former film overseas. It was released in most of Europe and the US between 1929 and 1931. Because of the movie’s accuracy in regards to rocketry it was banned by the Nazis in 1933. As opposed to a lot of German pre-WWII films this one has actually remained available in its entirety since its release, a fact that has probably also lessened its mystique somewhat. It was re-released in cinemas in West Germany in 1971, and underwent a restoration process at the F.W. Murnau Foundation in 2001. The restored version is readily available on DVD and can be found in good quality on YouTube.

Janne Wass

Woman in the Moon (Frau im Mond). 1929, Germany. Directed by Fritz Lang. Written by Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou. Scientific material written by Hermann Oberth. Starring: Willy Fritsch, Gerda Maurus, Fritz Rasp, Gustav von Wangheim, Klaus Pohl, Gustl Gstettenbaur. Cinematography: Curt Courant. Scientific advisor: Willy Ley. Art direction: Emil Hassler, Otto Hunte, Karl Vollbrecht. Special Effects: Oskar Fischinher. Produced by Fritz Lang for UFA.

Leave a comment