The first team of explorers to Mars are welcomed and double-crossed by a Martian civilisation attempting to hijack their rocket and invade Earth. A 1951 low-budget effort by Monogram, the movie’s striking for its visuals, but badly scripted and routinely directed. 5/10

Flight to Mars. 1951, USA. Directed by Lesley Selander. Written by Arthur Strawn, inspired by novel by Aleksei Tolstoy. Starring: Marguerite Chapman, Cameron Mitchell, Arthur Franz, Virginia Huston, John Litel, Morris Ankrum, Richard Gaines, Lucille Barkley, Robert Barrat. Produced by Walter Mirisch. IMDb: 5.2/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritc: N/A.

1951 was a tremendous year for science fiction films in Hollywood, especially for films concerning space travel and aliens, subgenres that had only found their way into full-length cinema the previous year. In 1950 producer George Pal had tried to depict a scientifically accurate flight to the moon in Destination Moon (review), and Lippert Pictures had jumped on the wagon with a voyage to Mars in Rocketship X-M (review). In the first two thirds of 1951 spacemen came to Earth, first in The Man from Planet X (review), then in The Thing from Another World (review) and later in The Day the Earth Stood Still (review).

The scientists in Rocketship X-M discovered a Martian civilisation destroyed by nuclear holocaust, and sent back a warning so dire that people on Earth started travelling to the centre of the Earth to escape disaster in Unknkown World (review) in October. They found no more life there than some deep sea fish, but must have disturbed something, because a month later small furry Mole-Men started climbing up to the surface in the first Superman film, Superman and the Mole-Men (review). Such terror did they spread that George Pal built himself an interplanetary Noah’s Ark in When Worlds Collide (review) in November, around the same time that producer Walter Mirisch sent his own team of scientist out in space in Flight to Mars. This was no prestige production, but a low-budget pulp story filmed in little more than a week than by director Lesley Selander at Poverty Row studio Monogram. And with that in mind, it looks absolutely amazing!

The script was written by allround writer Arthur Strawn, best known for devising the story for the 1935 Boris Karloff vehicle The Black Room. The movie borrows heavily from Destination Moon and Rocketship X-M during the film’s first half: the flight crew is presented along with their specialities and their motives for going on the trip, and we get a build-up to the take-off. We meet the wisened egghead scientist Professor Jackson (Richard Gaines), the brilliant, ambitious engineer, Dr. Jim Barker (Arthur Frantz) and his girlfriend/colleague and token woman scientist Carol Stafford (Virginia Huston), the gloomy skeptic scientist Dr. Lane (John Litel), and the staple reporter of forties and fifties sci-fis, and our leading man: Steve Abbott (Cameron Mitchell). Abbott is the representative of the “average Joe” on this mission, and is just as annoying as these representatives tend to be in these films.

Unlike the previous space voyage films, Flight to Mars doesn’t bother with laying out the principles of space travel, but briefly gives more or less the same story as Rocketship X-M: nuclear power will take us to Mars, and that’s more or less the extent of the science in the movie. The science isn’t the only thing borrowed from Rocketship X-M; Monogram was also able to purchase the spacecraft’s cockpit from Lippert Pictures. There’s even a mention of the same ”gyros” that keeps the floor of the cockpit facing ”downwards” during the whole flight – which would of course be redundant if the crew was weightless in space. Since the movie was filmed in less than two weeks, Monogram had no chance of creating any weightlessness effects, and thus cheats away that issue by inventing something called a ”field stabiliser” – and thus we get the first example of artificial gravity in a movie.

The first problem in space is the gravity of the moon – somehow these brilliant scientists haven’t been able to calculate whether or not the moon’s gravity will effect the ship, a fairly simple slideroll calculation, one might think. When pulled towards our Luna, the team makes a wild race-car turn to put themselves on the right trajectory. And just like in Rocketship X-M, they also encounter a surprise meteor shower. And this time the meteors aren’t just surprising, they also fly around completely erratically, like a swarm of fireflies buzzing around. And like the previous film, there’s also some tensions between the crew members and a love triangle between a male scientist, a female scientist and the everyman on ship. In Rocketship X-M it was the mechanic, here it is the journalist. There’s also the same discussion over whether a woman can be both a scientist and ”feminine” at the same time, one of those irritating tropes persistent throughout all fifties sci-fi (on screen). And like in that other film, the crew also gathers in the cockpit to ponder over life and the universe. Only the dialogue was far better written in Rocketship X-M. In Flight to Mars the lines are absurdly clunky and out of place, as when Abbott suddenly blurts out ”Sometimes I wonder who I am”, and nobody as much as giggles.

Rocketship M.A.R.S. crashlands on the red planet, which isn’t so much red as white, as it is covered in snow, and they discover strange ”chimneys” sticking out of the ground (after having traversed the planet wearing nothing much more than winter gear and oxygen masks, just like in Rocketship X-M). Suddenly they are greeted by a welcoming committee of Martians, who look just like humans and even speak English, as they have ”monitored your radio transmissions”. So well have they monitored that they even seem to be speaking English amongst themselves. The Martians all wear space suits because of the lack of oxygen – and if they look familiar, it’s because they were hand-me-downs from Destination Moon.

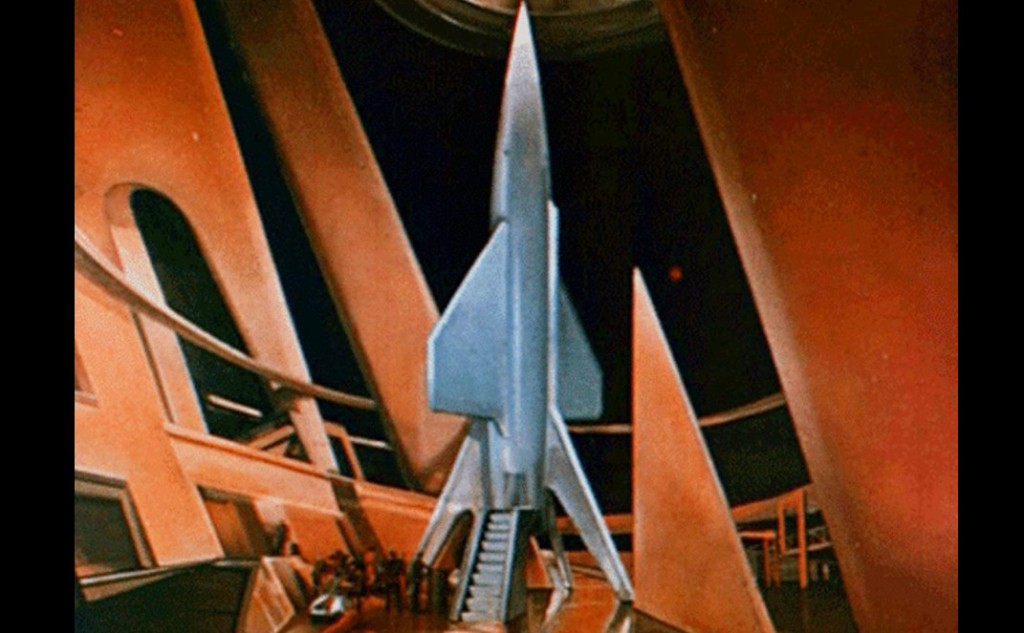

The Martians seem benign and welcoming, and inform our travellers that they live underground as the conditions on the surface are hostile. Life on Mars seems very much like life on Earth, except the architecture seems based on triangles rather than rectangles. All men are middle-aged or old and hold all positions of authority, and are dressed in Flash Gordon-styled garb. The women are all young and beautiful and all wear very, very short miniskirts, high-heeled boots, pointy bras and ridiculous shoulder pads. One can clearly hear the sarcasm in the actress’ voice as she tells the Earth people that they find the clothes ”very comfortable”. The travellers marvel at the underground city, powered by a radioactive material. But Carol Stafford’s first question is ”Where’s the kitchen?”. And no marvel is greater than the realisation that the Martians have created technology that both prepares food AND does the dishes. ”Mars is a heaven for women”, Stafford gasps.

Leader of the Martians is Ikron (sci-fi stalwart Morris Ankrum), who is very interested in the Earthling’s spaceship, as the Martians have spent too much time perfecting shoulder pads and automatic kitchens and too little time thinking about rocket science. They agree to help out repairing the damaged space ship, so that the Earthlings can return home. The most capable scientist is a young woman named Alita (top-billed Marguerite Chapman), who falls in love with Dr. Barker, creating a clumsy and wholly unnecessary love rectangle between the two, Abbott and Stafford.

However, Alita overhears Ikron and his closest lackeys speaking of sinister plans. The radioactive fuel of Mars is running out, and the Martians need a new planet to live on. Ikron plans to kill the Earthlings as soon as the spaceship is repaired, build more ships and fly to Earth to invade a new planet for themselves. And thus starts the third and final chapter of the movie, as Alita and her father, councilman Tillamar (Robert Barrat) try to help the Earthlings escape, while Ikron and his men and women prepare traps for the travellers.

The first half of the plot, as said, is very much derived from Rocketship X-M, and the latter part of the movie feels partly lifted from old serials like Flash Gordon (1936, review) and Undersea Kingdom (1936, review), or perhaps more precisely, their literary inspirations in comic books and pulp magazines. One interesting fact is that there are some similarities with the Russian silent classic Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924, review) — the most obvious being that Marguerite Chapman’s character is called Alita. And while much of the story is pretty much standard pulp fiction fodder, there are perhaps a bit too many converging plot elements for it to be just a coincidence. But more on that a bit later.

The biggest pitfall of the film is the scripting of the second half of the movie. Although often clumsy, stilted and honestly quite dumb, at least the first half has some sense of suspense and action, but as soon as the travellers settle on Mars we are treated to endless scenes of people sitting in rooms talking. Considering the film is actually set on an alien planet, it is hugely disappointing that the proceedings amount to mundane mobster movie plotting and an incredibly forced and unconvincing love rectangle completely devoid of emotion, save for a drawn-out crying scene courtesy of Virginia Huston. The only action, even that tepid, is saved for the last five minutes of the movie, and consists of some running through corridors and a few fisticuffs. The dialogue is simply atrocious. Most of it is exposition and techno-babble, and because the film had neither time nor money to actually show us Martian society, much of the latter part of the movie is taken up by the characters describing to each other this society — punctuated by characters almost looking straight at the camera, gushing “Oh, these fruits are really good!” And when the film occasionally strays away from the techno babble, you wish it hadn’t. The love rectangle at the heart of the drama is cringe-worthy and the character motivations involved here are difficult to swallow. I’ve always found it extremely difficult to believe that a team of trained professionals setting out on a highly dangerous mission involving precise cooperation would really that this was the appropriate time for domestic squabbles and cheating on the boyfriend with the mechanic. And the lead character in Flight to Mars, the journalist, is the one who wins over the girlfriend, and he does it by being an absolute dick from the beginning to the end of the film.

Now, back to that Aelita connection. On the surface there are only the most superficial of similarities between Flight to Mars and Yakov Protazanov’s 1924 Soviet barnstormer. A team from Earth make the first trip to Mars, where they are confronted by an evil ruler. One of the protagonists falls in love with a Martian maiden, our heroes are double-crossed and finally have to fight their way back home to Earth. Yes, there are similarities, but these are the most bare-bones outlines for almost any pulp story about a trip to Mars. As anyone who has seen it can testify, the plot of Aelita: Queen of Mars is very, very different from that of Flight to Mars. Much of Aelita actually takes place on Earth, and revolves around three (male) characters and their difficulties adjusting to post-revolutionary life in the Soviet Union. For one reason or the other, the slow, unglamorous drudgery of rebuilding society don’t sit well with the three men, who instead head off to Mars on an adventure, where they aid the down-trodden workers stage a communist revolution on their planet — all while being manipulated by the scheming Aelita (who is actually a princess and not a queen, despite the English title). In the end it turns out that the aristocratic Aelita can’t wash away her bourgeois heritage, despite promising herself to the revolution, and our heroes realise that “the revolution eats its own children”. While not a critique on socialism as such (it was a state-approved film after all), it can be, and probably should be, read as a critique of romanticising revolution, while forgetting that building societies requires the slower process of evolution. While a box-office success, Aelita was panned by the formalist Soviet film brass and the critics at the state-controlled media, who had little difficulty deciphering its subversive message. It did reach the US in 1929 under the title Aelita: Revolt of the Robots, but with little fanfare and even smaller box-office numbers. Soon after this, the film was suppressed by the USSR censors, and rarely seen anywhere until the eighties. Its legacy was chiefly carried on thanks to widely circulated promotional stills showcasing the memorable constructivist sets by Yuri Zhelyabyzhsky and the costumes by Aleksandra Exter.

So, Flight to Mars clearly isn’t a remake of Aelita. But there’s a but: Aelita: Queen of Mars actually wasn’t a faithful adaptation of Aleksei Tolstoy’s 1923 novel Aelita. Tolstoy’s novel is a space romance inspired by writers like Garrett P. Serviss and Edgar Rice Burroughs (with elements from the writings of Helena Blavatsky and Edward Bulwer-Lytton), and its plot, while very different, is much closer to that of Flight to Mars than to Protazanov’s rendering of Aelita. It’s not close enough to definitely pin Flight to Mars down as “based on” Aelita, but there a pretty good case to be made that screenwriter Arthur Strawn had read the book and used a number of its ideas for his own story. For example both the novel and the 1951 film use the notion of Mars as a dying planet as the driving force behind the drama — a theme that is notably absent from the 1924 Soviet film. Both also depict the rulers of Mars more like a technocratic oligarchy than as a Tsarist empire. And instead of a princess, Aelita/Alita is the daughter of one of these leaders, and becomes a faithful ally to the Earthlings rather than a double-crossing schemer. The Martian society depicted in Flight to Mars likewise much more closely resembles that of Tolstoy’s book that that of Protazanov’s movie.

And here’s the real sales-pitch for my theory: Aleksei Tolstoy‘s novel first appeared in English in 1950, a year before Flight to Mars was made. True, as a product of the Soviet state-run Foreign Language Publishing House, it probably didn’t make its way to the bookshelves of an awful lot of American homes, but screenwriter Arthur Strawn, a rather anonymous Hollywood figure, was one of the many casualties of the Hollywood blacklist, because of his left-wing sympathies. He seems to have fallen off the map after his blacklisting in 1952, and there is little to no information about him online. But if he did have communist sympathies, or even belonged to the Communist Party, he would probably have had easy access to a copy of the book. So no, the script of Flight to Mars is not inspired by the film Aelita: Queen of Mars, as is often claimed. However, there is much evidence that it is at least to some extent inspired by the source novel.

Another interesting thing about Flight to Mars would be easily explained by Strawn’s leftist sympathies, and that is the conspicuous absence of the Red Scare factor so prevalent in space exploration movies of the era. There are no allusions to the Soviet Union, or “the enemy” in the entire film, nor are there any overt references to the ideological strife or geopolitical tensions on Earth. In most movies of this type in this era, the driving force behind the American effort to explore space is to get out there before “the enemy”, but in Flight to Mars the reasons for the expedition are always referred to as strictly scientific. And while there is he case to be made that the hostile Martians could be seen as stand-ins for the communists, and were probably perceived as such by much of the movie-going audience, there is little in the actual script to make this case, other than convenience.

Although Flight to Mars is a cheapo production it doesn’t feel slapdash, and probably looks more expensive than it was. The design seems more hampered by budget than by imagination. The sets are sparse but striking. The slanted walls and hallways give Mars a feel of being inspired by the triangle rather than by the square, as on Earth. Nevermind that this is a highly impractical way to design a city, leaving masses of unusable space — something which you don’t have to worry about when building a pyramid in a desert, but surely wouldn’t be the design of choice for anyone trying to fit an entire society in caverns underground. One thing that does seem inspired by Aelita, the film, is the architecture – just like in that film the Martians seem to eschew rectangles, and instead we get curved lines, triangle-shapes and spiky design elements. There is a definite Bauhaus vibe going on, with the contrasting lines, flowing curves, symmetrical patterns and the two-dimensional look of the Martian architecture.

Otherwise little effort has been put into designing furniture for Mars, which seems to come straight out of the nearest departments store, or more likely, from the studio lobby. On the other hand, as humans on Mars seem to be identical to humans on Earth, it is likely that they would have happened on the same designs of everyday objects. After all, there are only so many ways to design a chair or a table. In this case, production designer Ted Haworth has decided upon white plastic chairs that people thought looked so futuristic in the fifties. The space ship looks very much like a miniature toy, and borrows its sleek look from Destination Moon, but it looks quite nice and was re-used in a few other films, like World Without End (1956, review), Queen of Outer Space (1958) and It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958).

The direction by B-western specialist Lesley Selander is workmanlike and he doesn’t get much help from extremely prolific cinematographer Harry Neumann, with over 300 films to his name, all of them B movies, including the sci-fis The Jade Mask and Roger Corman’s The Wasp Woman (1959). The lighting is uniformly flat, the camera angles boring and Selander does absolutely nothing to liven up the action. However, the film is one of the first sci-fi films to be shot in colour – and the first to use the newly invented SuperCinecolor process, a three-strip process based on the old Cinecolor process. The new technology reduced the lighting requirements and thus the costs, and made it possible to make colour films almost as cheaply as black-and-white films. It also enhanced the colour spectrum from previous subtractive two-strip colours to three strips. But instead of using magenta, cyan and yellow subtracts, it used red, blue and yellow matrices, that gave the film an ”oddly striking look”, as Wikipedia puts it. Indeed, the colour of Flight to Mars is oddly striking, and sets the film apart from many of its peers of the day.

The special effects are not at all bad for a movie of its day and budget, although the spacecraft is clearly dangling from wires, smoke from the spaceships’s rockets rise upwards in space, the meteors are simply red bokeh dots and the rocketship’s sudden turns are represented by the cast simultaneously throwing themselves sideways. It’s clear no photograph’s of Earth had yet emerged from outer space, since our beautiful blue planet is presented as a grey mass of play-dough. But for example the spaceship’s takeoff scene is better than in many consequent low-budget sci-fi films, and was re-used in a number of A movies.

The music of the film isn’t particularly memorable, but follows the same professional standard as the rest of the movie with its orchestral score. Composer Marlin Skiles was a studio veteran who had worked extensively on film serials, including many sci-fis, and ended his career in TV in the sixties. He scored a number of B sci-fis during the fifties and sixties, including The Maze, The Giant Claw (review), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957, review), Queen of Outer Space, The Crawling Hand (1963), Space Probe Taurus (1965), Journey to the Center of Time (1965) and The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler (1967).

Just how quickly the film was made is not immediately clear. The often touted figure of five days comes from an interview that film historian Tom Weaver did with actor Cameron Mitchell, in which Mitchell states that it was shot “in like five days”. This statement should be taken with a grain of salt, as Mitchell also confesses to not remembering making a number of pictures he appeared in. Shooting any feature film in five days is nigh impossible, at least if you’re going to do more than one take of each shot, which Mitchell mentions that director Selander at least occasionally did. Shooting an SF movie set on a space rocket and Mars in colour would be an almost superhuman achievement. Other sources claim the movie was filmed in 11 days, which is probably closer to the truth at least. Mitchell, of course, later became a staple of horror and exploitation, and a favourite of Mario Bava’s. In the interview this former Broadway up-and-comer seems to have no regrets that he became a poster boy for B horror and SF, as it allowed him to see the world (he did films literally all over the globe) and experiment with his acting in ways that a more conventional career wouldn’t have allowed. He has fond memories of working on Flight to Mars, which was his first forage into SF territory, and of his co-workers: “I remember I really enjoyed working on that film; I don’t know why, but I did!”. But he also states that he’ embarrased to look at the film today “because my performance was awful”. Agreed.

More than anything, Flight to Mars is a wonderful time capsule that tells us much more about the early fifties than it does about outer space. This was still a time when men were men, and when you couldn’t quite trust the learned minds to get you out of a tough spot without the help of a real blue-collar dude. It was a time when space was still a big, dark mystery, full of promise and horror, much like the new technology that mankind was tentatively probing. Despite the fear of of nuclear war, the fifties were a time of unbridled techno-optimism, a time of rising standards of living, when technology wasn’t simply there to serve manufacturing, but to bring comfort and ease to domestic life. Take the food processor of Mars – how different is it from the aluminium-wrapped TV dinner that was slowly starting to roll out in the US the early fifties? It was also a pivotal time in the battle of the sexes. Feminism was on the rise, and could not be ignored by movie makers, but still professional women were treated as an anomaly, and the question of what it meant to be a woman – a real woman – was the debate of many a Hollywood film. The notion that a working woman dedicated to her career could not at the same time be romantic or harbour notions of family life was rife within science fiction films – this was not the first fifties sci-fi movie to explore the topic. And more often than not, these brilliant young women were reduced to serving coffee and scrubbing floors – or indeed marvel over the automatic dishwasher.

Today the design of Flight to Mars doesn’t exactly feel futuristic, but instead smells remarkably like the fifties, with the inclusion of the hotly debated mini-skirt, the fifties hairdos and the shoulder pads. That the ”liberated” women of Mars would walk around all day in stiletto heels showing off their long legs is also an interesting notion of feminism – and Mars doesn’t seem to have much grasp on the concept of equality. A female scientist is OK, but there’s a conspicuous lack of women on the executive board. As so often what we seem to think is oh so futuristic often just turns out to be a defining feature of our own time – just look at those plastic chairs in Flight to Mars. Even Stanley Kubrick would later fall for this fallacy. Mars looks not so much different from a newly built US diner in the fifties.

On the subject of equality civil liberties – a notion that must be brought forth is the fact that all Martians seem to be Caucasian – or do they? Here’s an interesting observation I’ve made, that doesn’t seem to be brought up anywhere else: In the scene where the Martians first greet the Earthlings, one of the Martians looks very much a black man. Look at the picture above at the left hand side at the man in the teal space suit – isn’t that a black actor? Now, it may be that the Cinecolor, the shadows and the grainy YouTube copy I’ve been watching plays tricks on my eyes, but I could swear that it is not the same actor in the teal suit — a Caucasian actort — stepping out of the elevator a few minutes later. To my eyes, it looks as if that first meet and greet scene involves a black actor who is never again seen in the movie. My theory is that somewhere along the line someone had the idea to show Mars as multi-ethnic society, but for one reason or the other that notion was dropped, but I won’t go into further speculation. It is a shame, though – if the filmmakers would really have made a multi-ethnic, equal society on Mars it would have been something to be remembered for. But as stated, it could just be my eyes playing tricks on me.

All in all Flight to Mars does have a few firsts – it’s the first serious Hollywood film to encounter an intelligent, advanced civilisation in outer space (not counting the musical comedy Just Imagine, 1930, review) and the first to actually bring out the beautiful vixens of Mars/Venus/the moon, a tiresome staple of a number of later exploitation films. Flight to Mars was undoubtedly an exploitation film with its cheap sets and re-used scenery and space suits, but the colour photography and the fact that the team obviously have made an effort to make the thing look good sets it apart from many later Z movies. So good was it that for example a vista of the Martian city and its flying – something – (cars, elevetors?), its spaceship and takeoff scenes were re-used in a number of movies, often by the same effects team, though. The big problem is of course the script, which is tepid and dull and fails to take advantage of the wonder and adventure that a flight to Mars invariably promises.

The acting is in no way spectacular, although not overtly bad, either. One could perhaps call it uninterested. Marguerite Chapman as Alita was the biggest star of the film, and got top billing, despite the fact that she doesn’t appear until the second half of the movie. Cameron Mitchell was a good actor, a Broadway up-and-comer and on the brink of his big breakthrough in the fifties (he was considered at one point for Marlon Brando’s role in On the Waterfront) after his big success on stage and film with Death of a Salesman (1951). But for one reason or the other, Flight to Mars became more emblematic to his career than the fact that he was the first person ever to recite the script of Death of a Salesman — alone, in a hotel room with playwright Arthur Miller as his audience. In Flight to Mars, he carries the film with his nonchalant charisma, even if his character is woefully written.

I haven’t found any contemporary reviews of Flight to Mars, but modern critics seem to regard it on the scale from terrible to campy fun. Damien Taymans at French Cinemafantastique gives it 1/5 stars, calling it “a prime example of Monogram’s low-budget pictures and the hyperactive science fiction exploitation in the fifties”. AllMovie doesn’t even have a review of the film, but awards in 2/5 stars. Chris Barsanti writes in The Sci-Fi Movie Guide: “Notable as the first color movie of this genre, it’s still static and uninvolving — Flash Gordon with no flash. Turn down your TV brightness, and this talky opus could pass for a vintage radio play.” And in his celebrated encylopedia Keep Watching the Skies, Bill Warren states: “Director Lesley Selander […] isn’t so much a creative workers as merely the man to turn the script into a film. […] The pacing is leaden throughout.” Warren does concede that there ate a couple of interesting camera angles in the film, and that the spaceship model is “reasonably elegant”. However, his the overall film is in his mind, “lethargic”.

At DVD Savant, Glenn Erickson has a couple of nice things to say about the movie. He givs thumbs up to “interesting” special effects, “decorative” matte paintings, a “reasonable attractive” rocket and “fine” actors. However, “If Flight to Mars is a failure, it’s because it really isn’t about anything except a Martian doublecross. The plotting is as weak as a Flash Gordon serial, and the romance is even weaker. […] Alien civilizations meet, and the spaceman carries a Martian maid back to Earth, like Jason & Medea. Big ideas …but no payoff, zilch.” Still, this doesn’t bother Jeff Ulmer at Digitally Obsessed, who gives the movie a B- or 6/10 star review, writing: “Flight to Mars is a wonderfully campy little adventure. […] The plot is thin, the acting pedestrian, and the effects on the cheesy side, all of which combine to make a great sci-fi matinee, 1950s style.” Derek Winnert is also more than forgiving: “Especially considering time and budget restrictions, as well as of course the movie’s age, Monogram’s early space movie is fairly well made, if now endearingly naive seeming in Arthur Strawn’s simple-minded screenplay. It’s just a shame that it is so horribly cheaply filmed”. Winnert gives the picture a solid 3/5 star review.

I have seen the film half a dozen times by now, and every time I do I roll my eyes at the stupid script, the annoyingly ill-written characters and the terrible dialogue. But it’s a film that I always look forward to seeing again, and it’s one that’s stayed very vividly in my mind. The design of the Martian architecture and costumes may be silly and illogical, but at least it’s memorable. The plot may be simplistic and unrewarding, but it’s straightforward. It’s pure comic book pulp, albeit a very talky and slow-moving comic book.

First-billed Marguerite Chapman’s heyday was in the early and mid-forties, when she became a star as the leading lady in the hugely successful propaganda serial Spy Smasher (1942), followed by leading roles in the films Submarine Raider and Parachute Nurse the same year. She cemented her status as leading lady in an impressive number of B movies for second-tier studio Columbia, perhaps best known for her role as Russian woman trapped alongside Paul Muni’s Soviet officer in a building surrounded by Nazis in Zoltan Korda’s unusual pro-Soviet war film Counter-Strike (1945).

Chapman, a snappy, head-strong telephone operator and typist, had no acting ambitions, but agreed to try her hand at the trade after encouraged by her friends and discovered by Howard Hughes during a model gig. Although she was quite successful and had a steady run of leading roles during the entire forties, she was destined to be stuck in B movies, and her roles slowly got worse in the early fifties, som she decided to shift her focus to television, where she carved out a decent career as guest star on a number of TV series, sometimes doing the occasional film role. She continued acting until the mid-seventies. Her only other sci-fi role was the embarrassing The Amazing Transparent Man, where she still got top billing despite her rather faded star in 1960. She’s one of the better actors in Flight to Mars, but despite her long and exposed legs, she leaves no great impression.

Cameron Mitchell was an up-and-coming B movie leading man in 1951, possessing rugged good looks and a casual charm which has made him something of a cult favourite, despite his lack of defining roles. An actor with a stage background, Mitchell kept himself steadily occupied in leading or big supporting roles in both film and TV during the late forties and most of the fifties, and got something of a new start in the sixties as the star of a number of Italian genre movies, partly sword-and-sandal stuff, but also a number of horrors, or giallos, quite a few of them directed by cult legend Mario Bava. Between B movies and genre films, he thrived in a number of A efforts, like Death of a Salesman (1951), Les Miserables (1952), The Robe (1953, as the voice of Jesus), Désirée (1954, opposite Marlon Brando), the musical Carousel (1956) and Sergio Corbucci’s spaghetti western Minnesota Clay (1964). In the seventies he reinvented himself as a TV actor, perhaps best known for his leading role in The High Chapparal (1967-1971). Mist of all, however, Mitchell became a poster boy for weird B horrors and through his giallo fame became a favourite of slasher directors in the sixties and seventies.

Mitchell stayed clear of sci-fi until the late sixties, but then played the lead in Island of the Doomed (1968), Autopsia de un fantasma (1969), Nightmare in Wax (1969), The Big Game (1973), Supersonic Man (1979), Captive, Without Warning (both 1980), Frankenstein Island (1981) and Space Mutiny (1988).

Virginia Huston is perhaps best known for her stint as Jane opposite Lex Barker’s Tarzan in the fifties.

Arthur Franz is likeable, but a bit less spirited, in the role of the engineer. Franz’ career trajectory was very much like Mitchell’s, except Franz was often stuck as the sidekick character or in a supporting role. A prolific actor in B movies who sometimes did impressive work in A films like Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), Roseanna McCoy (1949), The Caine Mutiny (1954) and Fritz Lang’s Beyond Reasonable Doubt (1956). Franz also appeared in Invaders from Mars (1953), The Time Barrier, Monster on the Campus (both 1958), The Atomic Submarine (1959), and a number of sci-fi TV-series.

A lot of fifties sci-fi geeks seem to have something of a man-crush on veteran bit-part and supporting actor Morris Ankrum, whose reputation far exceeds his work, although he did some fine work throughout his career in most genres, almost invariably in B movies and often in westerns. Ankrum’s range wasn’t staggering, but his stern visage and authority was palpable and he always brought a sense of believability and weight to the movies he acted in. Ikron is not his greatest role, mostly because the material he gets to work with is wafer-thin. Plus, he lacks his trademark stache.

Rocketship X-M was his first sci-fi movie, and he went on to appear in Red Planet Mars (as secretary of defense, 1952, review), Invaders from Mars, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review), Kronos (review), The Beginning of the End, The Giant Claw (all 1957), How to Make a Monster, Half Human: The Story of the Abominable Snowman, Curse of the Faceless Man (all 1958), From the Earth to the Moon (as president Ulysses S. Grant, 1958), Most Dangerous Man Alive (1961) and Roger Corman’s X (1963). In the sixties he also became a well-known face among TV viewers, thanks to his recurring role as a judge on Perry Mason. This was all well in character, as he was actually an attorney before beginning a career in theatre.

Walter Mirisch would later go on to become one of Hollywood’s most regarded producers with films like Seven Angry Men (1955), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), The Magnificent Seven (1960), West Side Story (1961), The Pink Panther (1963), Hawaii (1966), In the Heat of the Night (1967) and Dracula (1979). And he is still going strong today at 94 years old, as producer of a new Pink Panther animated film slated for release in 2016. In 1951 he was still working himself upwards with B movies in the Poverty Row studio Monogram, which was soon to merge into Allied Artists, for which Mirisch would eventually become studio boss.

Production designer Ted Haworth went on to design the films Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Monster that Challenged the World (1957, review), the splendid, but frequently overlooked cult classic Seconds (1966) and *batteries not included (1987). Art director Dave Milton was a Monogram stalwart who had worked on films like Revenge of the Zombies (1943, review), The Ape Man (1943, review), Return of the Ape Man (1944, review), Voodoo Man (1944, review) and The Jade Mask (1945, review). He later worked on The Maze (1953), World Without End and Queen of Outer Space for Allied Artists.

The matte paintings of Mars are not necessarily realistic, but quite beautiful in all their pulpy glory. The matte work was overseen by industry veteran Jack Cosgrove, who did work on classics like The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review) and Gone with the Wind (1939), and was nominated for five Oscars during his career. He also worked on The Invisible Ray (1935, review), Invaders from Mars (1953), Monster from Green Hell (1957, review) and Queen of Outer Space. Uncredited special effects artists were the dynamic duo of Jack Rabin and Irving Block. Both had worked on Rocketship X-M, and went on to collaborate on Unknown World, Invaders from Mars, World Without End, Monster from Green Hell, The Invisible Boy, Kronos (both 1957), War of the Satellites (1958), The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959) and Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959). Both also worked on a number of other sci-fi films separately. Rabin worked on movies including The Man from Planet X, Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), Robot Monster (1953, review), Deathsport (1978) and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Block did work on films like Captive Women (1952, review), Forbidden Planet (1956, review) and The Atomic Submarine (1959).

Janne Wass

Flight to Mars. 1951, USA. Directed by Lesley Selander. Written by Arthur Strawn, inspired by Aleksei Tolstoy’s novel Aelita. Starring: Marguerite Chapman, Cameron Mitchell, Arthur Franz, Virginia Huston, John Litel, Morris Ankrum, Richard Gaines, Lucille Barkley, Robert Barrat, Trevor Bardette, Tristam Coffin, Music: Marlin Skiles. Cinematography: Harry Neumann. Editing: Richard V. Heermance. Production design: Ted Haworth. Art direction: Dave Milton. Production management: Allen K. Wood. Sound recordist: John K. Kean. Visual effects: Jack Cosgrove, Jack Rabin, Irving Block. Produced by Walter Mirisch for Monogram Pictures.

Leave a comment