(9/10) Often overshadowed by it’s remake, Howard Hawks’ 1951 adaptation of John W. Campbell’s novella is still a stellar picture. This ensemble piece was the movie that finally blew the door open for science fiction in Hollywood, and has inspired a generation of filmmakers. From Hawks’ famously superb handling of dialogue to the groundbreaking stunts and stellar acting, the movie is a bona fide SF classic.

The Thing from Another World. 1951, USA. Directed by Christian Nyby & Howards Hawks. Written by Charles Lederer, Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht. Based on novella by John W. Campbell. Starring: Kenneth Tobey, Margaret Sheridan, Robert Cornthwaite, Douglas Spencer, James Arness. Produced by Howard Hawks. IMDb: 7.1. Rotten Romatoes: 89/100. Metacritic: N/A.

After a tentative start in 1950, Hollywood finally sank its claws deep inside science fiction in 1951, releasing two of the most influential and acclaimed science fiction films in the history of cinema. The second of these was the liberal, pacifist classic known as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), about an alien landing in Washington to deliver a message of warning and of intergalactic peace. Five months prior to that, a completely different beast, set on destruction and world domination, crashed in the glaciers of the Arctic. This Thing from Another World was the later movie’s ideological counter-part, steeped in red-scare, militarism, science-bashing and paranoia. Despite the ideological differences, the films are equally revered, and the jury still seems to be out on which was the better entry. It has, however, reached the conclusion that few, if indeed any, sci-fi films of the following decade came even close to the quality of these to trail-blazers. And while the remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still (2008) starring Keanu Reeves has received an almost unanimous thrashing (I think it’s better than its reputation), John Carpenter’s remake The Thing (1982) has overshadowed the original.

The Thing from Another World opens in Anchorage, Alaska, when wise-cracking reporter Ned ”Scotty” Scott (Douglas Spencer) arrives at an airbase looking for a story, at the invitation of his old friend Captain Patrick Hendry (Kenneth Tobey), leading man and hero of our film. Hendry and his team, along with Scotty, head out to a secluded research station in the Arctic to investigate what they believe is a plane crash, but turns out to be a UFO that’s embedded itself in ice. After accidentally blowing up the spaceship, they find the pilot, hack it out in a block of ice and take it back to the research station.

A heated argument flares up between the military on one side, opting for taking the Thing back to the United States for analysis, ice block and all, and on the other side the scientists, led by the arrogant and calculating Dr. Arthur Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite), who want to keep it safe at the station. The argument resolves itself as the crewman left watching over the Thing accidentally thaws creature, which escapes the crewman’s gunshots out in Arctic desert, and soon the crew see a silhouette out in the freezing cold attacked by the sled-huskies. The creature escapes sans an arm, which the scientists take in for analysis, only to find out that the Thing is in fact a walking vegetable in humanoid form, leading to the one of the film’s many classic lines, delivered by Scotty: ”An intellectual carrot! The mind boggles.”

Dr. Carrington is beside himself with joy over the realisation that they have discovered ”a perfect life-form”, as the intellectual carrot reproduces asexually and is unhampered by human emotion or sexuality. Carrington and some of the scientists feel the creature should be kept alive for study and communication, while the military chaps feel it is a threat not only to those at the station, but humanity as a whole, and opt for killing it outright. But the problem is that the Thing is well on its way to killing all the people at he station before they may get their chance of offing it. Lurking in the freezing night or in Dr. Carrington’s greenhouse, the Thing slowly advances, striking in the shadows only to disappear again, and the team is at loss for a way to kill it. Until Carrington’s assistant Nikki Nicholson (Margaret Sheridan) muses that the thing you usually do with a vegetable is ”boil it, bake it, stew it, fry it”, which leads to one of the resourceful air force men coming up with the idea of dousing it with gasoline and lighting it on fire.

Said and done, in film history’s first attempt at a full-body burning stuntman, the crew set the Thing alight, only to watch it careen out of the station and put itself out in the snow. Now it’s really pissed, and the crew is out of options. Can the military and the scientists work together to find a way of killing the Thing before they are all (ironically) eaten by the giant vegetable?

There’s more to the story, but I’ll get to that later. The film is based on a 1938 novella called Who Goes There, written by author and legendary SF pulp editor John W. Campbell. The 1951 film is a very loose adaptation, taking only the very basic premise of an alien crashlanding in the Arctic and wreaking havoc on a science station, and pretty much makes up the rest from scratch.

The novella, counted by many among the best works of horror SF, and winner of numerous awards, is a claustrophobic, paranoia-drenched piece describing the proceedings on a science station after the science team find a UFO, accidentally blow it up and then dig out a frozen alien pilot. No army is involved, and the debate over whether to keep it alive or killing it quickly dissipates after it kills one of the huskies – or rather tries to shape-shift using the body of one of the dogs. The paranoia of the novella comes from the fact that the Thing is able to take on the form of any and all of the scientists, and has obviously done so to some extent, and on top of that, is telepathic. There’s seemingly no knowing who is human and who is a monster, and while the Thing plays Ten Little Indians with the crew, stout meteorologist McReady must try and find a way to save what is left of his crew, and prevent the Thing from leaving the station and enter the bustle of the outside world. If you’ve seen Carpenter’s film, you pretty much know the story, as that was a very faithful adaptation, as opposed to the 1951 film.

The original movie was scripted by none other than producer/screenwriter/director Howard Hawks, known for legendary films like Scarface (1932), Bringing Up Baby (1938), His Girl Friday (1940), The Big Sleep (1946), Monkey Business (1953) and Rio Bravo (1959). On the writing team were also two of his favourite screenwriters Charles Lederer and Ben Hecht, who contributed to many of the above mentioned movies, as well as Gone with the Wind (1939), Wuthering Heights (1939) Notorious (1946), Ocean’s 11 (1960), Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) and Casino Royale (1967). The trio’s only other connection with real SF is Ben Hecht’s work on Queen of Outer Space (1958), perhaps not his proudest moment.

The hard-boiled crime thrillers and screwball comedies of Hawks and Hecht in particular, were characterised by their quick pace, their witty, naturalistic, street-smart and slang-infused dialogue, friendly macho banter and male camaraderie, as well as at least one tough-as-nails female character per film. All this is present in The Thing from Another World. It is a huge accomplishment of the script that it actually turns the ridiculous idea of a walking vegetable monster into a viable – and horrifying – idea without the film falling into the so-bad-it’s-good category. Instead it’s so good it’s one of the best sci-fi films of the fifties.

Hawks was nominally just writer and producer on the film, and it was made by Winchester Pictures Corporations for RKO, with whom Hawks had a two-film deal. Although the premise looks like something fit for a B movie, the budget was actually A film standard, making The Thing from Another World the first actual A-list science fiction film made in Hollywood. The film cost 1.6 million dollars to make, which with project-based inflation makes 11.8 million dollars today – 1.8 millions more than Carpenter had at his disposal when making The Thing.

One of the most enduring debates in SF film history is the one concerning who actually directed The Thing from Another World. On paper, director was Christian Nyby, the editor who had been nominated for an Oscar for his work on Hawks’ film Red River (1948), and had previously worked with Hawks on The Big Sleep. However, Hawks’ directorial fingerprints are all over the movie, most notably in the wonderful dialogue, which is one of the best aspects of the picture. Here, actors are not patiently waiting for someone to finish their sentence, but interrupt, cut off, overlap dialogues and sometimes three or even four characters are talking over each other at the same time. It lends the film a wonderful sense of reality and bounce. According to actor Robert Nichols, much of the dialogue was made up on rehearsals, and to get a naturalistic feel, Hawks would often take actors aside during filming and give them new lines to throw in while other actors were speaking, without telling anyone else – which led to a lot of real reactions, ad-libbing and adjusting. There’s also the noir-influenced lighting and the swift pace of the film, all bearing Hawks’ trademark – not to mention the themes of group dynamics, people working under pressure, the blending of humour and grim seriousness, etc. There is no doubt that Hawks had his hand in much of the direction.

It has been speculated that Hawks nominally let Nyby get the directorial credit because Hawks didn’t want to be associated with an SF B film. Hawks himself said that he did it out of courtesy to Nyby, who strove at becoming a director himself, and needed a direction credit ro register with the Directors Guild of America. Hawks said that Nyby had been of such help on his previous films, that he owed it to the editor to give him a go at directing. Hawks did, however, admit that he did rigorous rehearsals with the actors before shooting, especially concerning the overlapping dialogue, but always maintained that it was Nyby who directed. But cast members have since said that although Nyby was the designated director, Hawks was on set every day giving instructions, and according to some sources he took over much of the directing from Nyby. This is backed up by the fact that Nyby mostly worked on TV shows after this film, with the exception of the odd film, none of which came even close to the quality of The Thing from Another World. In the book Eye on Science Fiction Nichols says that Nyby was ”present” at all times, but that it was basically Hawks who did all the directing.

Thematically it’s a rich soup. There’s the red-scare, with the Thing of course representing communism, snatching up people like Dr. Carrington, who starts breeding little communist saplings of his own in his laboratory, and there are the brave patriots who stand up against the red (or in this case green) menace. But the most prevailing theme is one that had been around for decades: science scepticism. In many later films, perhaps most blatantly in Red Planet Mars (1952, review), religion was pitted against science, and within religion was also embedded the notion of American values. Thankfully, The Thing from Another World neither waves the flag nor thumps the bible. Instead it brings in the military. On the one hand you have Hendry and his men, set on destroying what could potentially be a threat to humanity, ignoring the scientific value of keeping the Thing alive. On the other hand you have Dr. Carrington and some of his men, set on keeping the Thing alive for the sake of science, willing to sacrifice a few human lives for a utilitarian purpose.

Unless you’re one of those crazy anti-vaxxers, you might ask yourself why one would go to such lengths to discredit not only some scientific branch or claim, but science itself. This was a rather new phenomena in sci-fi films – in earlier movies and stories the emphasis was almost always on scientists trying to play god; science itself was not the problem, rather scientists who tried to upset the balance of nature (or god, if you will). But the early fifties brought an increasing amount of movies that revolted against the concept of science altogether, in many ways mirroring the public debate. The main reason for this hostility was the atomic bomb. This was not so much in outrage over the happenings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but rather because of the fear of a nuclear attack on USA. Blame was laid for this threat on the scientists who had created the bomb in the first place – and as an extension on science as a whole. ”Science” in films was more often than not linked with shady foreign organisations and ”scientists” tended to have foreign-sounding names and accents. More emphasis was put on the fact that two of the great minds behind the bomb were Einstein and Oppenheimer, and films conveniently forgot that the Manhattan project that employed the scientists and financed the science was a US government project, and the only organisation in the world that had ever deployed a nuclear weapon, killing hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, was the US military. Instead, as in this film, the US military was often portrayed as the pure, moral counterpart to the calculating, moral-free science.

The handling of this conflict is the film’s biggest flaw, mainly because it is the one thing the viewer just doesn’t buy, and that is mainly because of the character of Dr. Carrington. That Carrington will be the secondary villain in this film is clear from the moment we set eye on him, decked out as he is in his flamboyant turtleneck jumper, cruise ship captain’s blazer, Russian-styled fur cap and gaudy fur coat, sporting a slick-back and a goatee. While it is never explicitly implied that he may have Soviet connections, the image the filmmakers are trying to convey is clear. Not only that, but his taste in clothes and certain mannerisms also makes it feel like the filmmakers are hinting at homosexuality, equally looked down upon by the greater public at the time. Combine this the with the third “negative” aspect – he is a scientist – and you’ve got your ready-made villain. But the problem with the character is that in the first half of the film Carrington comes off as quite a sympathetic and reasonable person. There is a great scene in which the teams are discussing the biological makeup of the Thing, where Carrington shows no signs of arrogance, humbly deferring to his colleagues in matters that he feels they are more knowledgeable about, chatting amiably with all involved. He doesn’t revolt against the military’s decisions during the first half of the film, but rather courteously lays down his arguments in a civilised manner, arguing for the scientific value of keeping the Thing alive – and pointing out that they are located in at a civilian science station on international territory, and the US military doesn’t have any authority to order the scientists around or confiscate research material – which is absolutely true. That’s also why it’s so hard to reconciliate the image of Carrington later in the film, where he outright refuses to have any harm done to the thing – even after it has killed several of his scientists.

Robert Cornthwaite does the role of Carrington with grace and wit, making the best he can out of the difficultly written character. As a modern viewer you actually often find yourself sympathising with Carrington rather than with Hendry and the military, despite Carrington’s sometime obnoxious traits. Carrington even comes off as a heroic character in the final scene. it. In the end, he also receives the forgiveness of the military – this was a last minute script change, as Hawks probably also thought that Carrington had been rather mistreated throughout the movie.

There’s also the fact that the film – if you simply look at the plot – is a resounding praise of the scientific method. The odd thing is that the screenwriters have completely reversed the structures of the two groups involved. The scientists are a strictly top-down led entity. Dr. Carrington is the indisputable general, whose word is law, and all other scientists are clearly subordinates. Those who disagree are viewed as deserters and shunned. As proceedings get going, Carrington never engages in discussions, but gives orders, and refuses to listen to advice. This is usually the way the military works. On the other hand, the military group is led by Captain Hendry, but his authority lies in the respect his subordinates have for him as a man, rather than his rank. The whole group seems to work more or less on democratic principles and the subordinates frequently make fun of Hendry, jeering and taunting his romantic escapades, and he, in reverse, frequently asks his men for advice and often admits he doesn’t know how to handle a certain situation. Almost all of the conclusive ideas come from someone else than Hendry.

Furthermore, despite the fact that the military wants to kill the Thing, they go about the project in a very scientific manner. First of all, it is the actual scientists that work out exactly what sort of enemy they are dealing with, and without them, the army guys would have been dead in minutes. Second, in working out a plan, the military group first gather the data, then work out a hypothesis, put together theories that they lay out for peer review, as it were, and only when they think they have an actionable plan, they set about testing it. After their first plan backfires, they scrutinise what went wrong, what parts of it worked and what parts didn’t, then revise it from evidence they have gathered, and formulate a new plan. This is exactly how science works.

Dr. Carrington, however, works from a dogmatic point of view and refuses to take in new information or change his plans even though his claims are scientifically refuted. Despite the fact that the Thing has shown no interest in communication, despite the fact that all signs lead to the fact that the whole team will be killed, he stubbornly believes that the alien is benign and willing to communicate. This is not the way science works. Added to this is the fact that Hendry never questions the basic idea that keeping the thing alive and gather information from it would be a wonderful thing. It’s just that in his mind, the danger the alien represents outweighs the possibilities of future knowledge.

The female lead Nikki Nicholson (Margaret Sheridan) is a major, active character in the film, as opposed to a lot of other female leads in sci-fi. Altogether, the romantic features of The Thing from Another World are unparalleled in fifties genre film, giving the female character the upper hand in the relationship, even going so far as making the male lead seem like a bit of a womanising jerk. The two seem to meet on an equal plane, and Hendry is never patronizing nor overly protective of his girlfriend — neither does Nicholson refrain from giving it to him straight as she sees it.

Before you get the idea that this is some feminist epic, I should point out that Nicholson still goes around asking the boys if they want coffee, and seems to be the one worrying about the house-work (apart from the Asian chef that shows up in the background and is never seen again) on the station. When attacking the Thing with fire, she is the one taking cover behind a mattress, and her one great contribution about what to do with vegetables is of course derived from her experience from cooking. Nevertheless, her character is probably the strongest and most independent of all female characters in science fiction films of the fifties – and the reverse is that Hendry is one of the most nuanced heroes in terms of male stereotypes in a science fiction film of the fifties.

The comic relief of the film is the wise-cracking reporter Scotty, but even the comic relief carries a lot of weight and seriousness in this movie. Between all the wise-cracking and the failed attempts to get a photograph of the thing, he also gets into the action. And when told to get lost for his own good, because he ”doesn’t belong” in the heat of battle, he gets offended and quips: ”I didn’t belong at Alamein or Bougainville or Okinawa, either. I was just kibbutzing!” At other times he comes off as a bit too much of a comic book character, as when he excites ”Oh, boy, what a story!” with an actual fist pump after they discover the UFO, or indeed when uttering his ”intellectual carrot” line. But he does bring a very lively energy and some lightness in the grim proceedings. He also gets to utter the famous last line of the film: ”Everyone of you listening to my voice, tell the world, tell this to everybody wherever they are. Watch the skies! Everywhere! Keep looking! Keep watching the skies!”

The influence of The Thing from Another World has been rightly noted. It was the first actual alien monster film and its claustrophobic atmosphere of chasing – or being chased by – an alien in the dark of cramped hallways or tunnels in an inescapable environment (space, under water or in the arctic cold). It’s also the first feature film containing the sort of alien spawning that would later turn up in movies like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (review), although in this film it simply feeds on blood, rather than take over human bodies. The influence on Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) is unmistakable.

Of course, no films are created in a vacuum. Alien invasions had been a staple in SF stories since the late 19th century, notably in H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), but perhaps even more interestingly for this film, in Australian writer Robert Potter’s The Germ Growers from 1892, in which incorporeal aliens take over the minds of humans and start cultivating deadly germs. Wells, of course was one of the first to conjure up actual alien monsters. And since then, pulp magazines and comic books had been full of monsters in all imaginable shapes and sizes, so the idea was hardly novel. What was novel, though, was the way in which Hawks and Nyby incorporated one in a serious A-list movie. However, there isn’t much in terms of look or behaviour that distinguishes the Thing from the Frankenstein monster in Frankenstein films in the late thirties and early forties. The fact that it feeds on animal blood feels like a somewhat unimaginative solution, making the creature – in effect a Dracula-Frankenstein hybrid. The one novel thing about it is making it a vegetable and having it spawn through seed pods and saplings, a concept that hasn’t been used in too many sci-fi films through the years, although a few instantly spring to mind.

In Campbell’s novella, the alien’s true form was much different from what ended up on screen in both this film and the 1982 remake. Campbell described it as biped with a terrifying, evil face, three red eyes and a skin that was covered in some sort of fur-like substance that looked like ”blue, writhing worms”, and describes it as having tentacles shooting out from below its neck.

The setting and the mood of the film – an isolated building (or science station or spaceship) with an unseen killer on the loose, blanketed in shadows and torn by howling storms and rain (or a blizzard), harks back to the late twenties and early thirties. It is basically the setting for an old dark house movie, like The Bat (1926) and The Cat and the Canary (1927), films that inspired James Whale and Robert Florey to create the setting of Frankenstein (or indeed Tod Browning to create the setting of Dracula in 1931). But these films had even earlier precedents. What is the scene of Nosferatu’s shadow approaching Ellen Hutter in her bed in 1922, but a classic scene for an old dark house film. The expressionistic lighting in this German classic, along with other movies like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) or Alraune (Destiny, 1922) inspired the American horror movies of the twenties and thirties, and also influences the film noirs of the forties and fifties, a genre in which Howard Hawks was well versed. Agatha Christie of course perfected the Ten Little Indians trope with her 1939 novel Ten Little Niggers, a title which for obvious reasons was changed to And Then There Were None upon its 1940 release in the US, although similar plot elements – people getting killed off one by one by an unseen murderer – had been prevalent for decades in both literature and film. Some have pointed to Dr. Carrington as the archetype of the mad scientist, but that honour should probably go to Rotwang in Metropolis (1927), and the character was perfected in the shape of Henry Frankenstein in 1931. This does in no way diminish the quality of the film, nor the brilliance of the filmmakers that took all these familiar elements and created something new and fresh out of them – in the same way that it doesn’t diminish the brilliance of Alien that it took some inspiration from The Thing and Who Goes There?

The special effects of The Thing from Another World are few but effective. The scene of the spaceship blowing up is well done, and an early scene where they inspect the Thing’s arm that’s been ripped off by the dogs – and the hand suddenly starts moving on the table. Nichols says in the book Eye on Science Fiction that the stunned reactions of the actors are absolutely real. The arm was simply a plastic prop, but unbeknownst to the actors, Hawks had drilled a hole in the table, and a hole through the hollow arm, and had actor Billy Curtis hide under the desk and stick his hand up the ”glove”, and start moving it at the end of the shot. This technique of surprising the cast with an unexpected effect was famously used – and turned up to 11 – in the famous scene in Alien where the chest-burster explodes out of the chest of John Hurt.

One of the most effective scenes of the film is when the Thing is set on fire – head to toe. This was the first full-body burn seen on film, and the Thing was played by stuntman Tom Steele in the scene, wearing an asbestos suit and a fibre-glass helmet with an oxygen mask. According to Nichols, the actors were replaced with stuntmen in a continuous shoot without cutting and resetting, because not only was the Thing on fire, but the whole set.

The music by Dimitri Tiomkin has been much praised and rightly so – a lot of the movie is actually without music, but Tiomkin uses his bombastic orchestral score as emotional cues and throws in screaming, high-pitched notes at fright heights and action scenes, much like Bernard Hermann would later do with Psycho (1960) or John Williams with Jaws (1975). The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review) did this to the point of absurdity. In other scenes Tiomkin just lays in a barely audible, soft track of music to set the mood to either eerie (using oboe), or romantic (with a mellow jazz tune). During the course of his career he won four Oscars, several Golden Globes and Laurel Awards and was nominated for a Grammy and dozens of other awards. When you’re the one making the music for a biopic about Tchaikovsky, you know you’ve done something right.

Cinematographer Russell Harland does a wonderful job with tracking shots and superb setup and lighting. Harland was nominated for 6 Oscars. The art direction is superb, not least in the matching of studio-bound sets, backlots and actual snowy Glacier National Park in Montana, where the crew spent time waiting for snow – which is why The Man from Planet X (review) beat the movie to cinemas by a month. The science station is just as cluttered and realistic as you would expect it to be, the actual snowy glacier park adds some great sense of space and loneliness and the snow is ever present even in indoor scenes – it comes blowing in from open doors, it stays on top of caps and coats and flies by windows in the background. For interior sets chilled by broken windows or smashed generators the team built sets in a Los Angeles ice storage plant to get shots of steaming breaths. There’s also some use of matte paintings and fake snow – as in the scene where the teams find the UFO in the ice – I actually thought it was filmed in Alaska or somewhere, until I read it was filmed on a very hot day on a Hollywood backlot with a huge, curved matte painting in the background – a perfect illusion.

The monster itself was created by makeup artist Lee Greenway, best known for working on comedy and soap opera TV shows (he was the on-set makeup artist on The Andy Griffith Show from 1960 to 1968). He reportedly made 18 small-scale models of the Thing before Hawks was satisfied. To many modern viewers, the Thing – a man in a rubber suit – is disappointing. Actor James Arness hated the suit, not only because it was hot, but because he thought it made him look like a ”giant carrot” – which inspired Scotty’s famous line mentioned above. Of course, with the technology available at the time, it would have been impossible to do the sort of morphing character that Campbell described in the book, and one can suppose that Hawks instead looked back at the sort of monster movies that were available at the time – things like Nosferatu (1922) Frankenstein (1931, review), The Mummy (1932), etc. Some have argued that the Thing looks like a cross between Nosferatu and the Creature from Frankenstein, and the notion isn’t far off.

Reportedly all close-ups of the monster were removed in edit, since Hawks thought the makeup didn’t hold up . This actually works well for the film, as the Thing is almost always seen as a menacing presence in the distance, often obscured by shadow or as a silhouette. In the final scene, the monster shrinks when it is electrocuted, and was then played by short actor Billy Curtis.

At the time of the release of The Thing from Another World, mainstream press generally looked somewhat down their noses on SF movies, but Bosley Crowther of The New York Times gave the film a very positive review: “Not since Dr. Frankenstein wrought his mechanical monster has the screen had such a good time dabbling in scientific-fiction. […] Adults and children can have a lot of old-fashioned movie fun at The Thing, but parents should understand their children and think twice before letting them see this film if their emotions are not properly conditioned.” Variety gave the movie a more mixed reception. Staff critic “Gene” noted that the direction built “tingling expectancy” very well, but that that the film “lacks genuine entertainment value”. According to Variety “cast members […] fail to communicate any real terror”, and the screenplay “shows strain in its efforts to come up with a cosmic shocker”. Still, “Gene” concedes, “Dimitri Tiomkin’s music background, camera, editing and special effects are all good”.

Today, almost all agree that The Thing from Another World is a great film. AllMovie gives it 5/5 stars, and Hal Erickson writes: “A superior blend of science fiction, horror, naturalistic dialogue, and flesh-and-blood characterizations, The Thing is a model of its kind”. Empire likewise awards the film full marks, with William Thomas writing: “Building suspense through his masterly use of the unseen, Hawks brings an added chill to this tale of terror at the North Pole, that is also a disturbing study of communal paranoia and the fear of science. With a fine ensemble cast […] and a knowing script, this is superior to John Carpenter’s remake.” Time Out says: ” Reactionary or not, […] it’s still a masterpiece”.

TV Guide awards The Thing from Another World with 4/5 stars: “No ray-guns, strange costumes, or futuristic inventions are needed here; even the spaceship is only suggested, never seen. The fact that the alien closely resembles a man heightens the sense of personal, human struggle that is the cornerstone of all good drama.” Review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes has the film standing at a 89/100 Fresh rating based in 35 reviews, with the consensus: “As flying saucer movies go, The Thing From Another World is better than most, thanks to well-drawn characters and concise, tense plotting”. And Nick Schager at Slant Magazine gives the picture 3/4 stars, stating: “What’s most remarkable about The Thing is its continued ability to function as both a taut science-fiction thriller and a telling snapshot of the Cold War paranoia beginning to sweep the country in post-WWII America. The story […] is a model of economic storytelling.”

Somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, users at IMDb don’t give the picture a higher rating that 7.1/10. It would be easy to dismiss the critics as modern-day viewers who love the gore-filled and action-packed remake and don’t know how to watch old films. But interestingly enough, much of the critique from modern reviewers echo what Variety wrote in 1951. One frequent criticism is that the characters simply don’t seem frightened enough of the menace threatening them; there’s too much friendly banter, too many jokes and wise-cracks. Like Sylvia Bagley (who does otherwise give the movie a glowing review) at FilmFanatic states: “my only minor quibble with the film is that the characters never seem quite scared enough; they’re having such a grand, confident time together that one never doubts they’ll come through with flying colors.”

Another frequent criticism is that the movie “lacks genuine entertainment value”, to once again quote Variety. Or as pseudonym “Yo Adrian” puts it at Oh the Horror: [The Thing is] “dull and anticlimactic. Everything is exposition. There’s a lot of talk and little action.” Asbjørn Ness at Norwegian Filmdagbok does give the movie a decent 3/5 rating, but writes: “That the film uses a lot of time building up to something that in my opinions isn’t particularly dramatic, is it’s biggest weakness”. And Andy Kaiser at Andy’s Film Blog has this to say: “I find it bogged down by technical detail and jargon and am not sure I understood the central moral conflict from the point of view of the crackpot scientist or whether or not that was supposed to be taken seriously”. Phil Hubbs at Hubbs Movie Reviews echoes the statement, saying: “The movie really takes time to get going and I found myself yearning for just something…anything to happen! Alas when things do happen it’s also pretty slow, pretty tame, and pretty disappointing”.

Then, of course, there are those that dismiss the film because of its ideological stance. Matthew Foster at Foster on Film gives The Thing from Another World a 2/5 star rating: ” For a simplistic, conservative, anti-communist rant, The Thing From Another World is nicely made. […] Since this is the ’50, and viewing communists…ummm, I mean aliens…sympathetically is evil, the lead scientist is given the view that the alien is superior because it lacks emotion and sex; it would be better for all the humans to die if that would allow the alien to live. Not exactly a position that’s going to get a lot of support, nor one that puts any interesting debate into the film.” I have sometimes cracked jokes about Andrew Wickliffe at The Stop Button giving a number of beloved B movie classics zero-star reviews. Unsurprisingly, he isn’t sold on The Thing either. But to his credit, he gives credit where credit’s due, and awards the film 3/5 stars: “The film’s problems are those of its era, which–try as they might–can’t defeat its superiority”.

Finally, some simply compare the film unfavourably to either the source novella or the remake. The above-mentioned Phil Hubbs is one of those most disappointed in the fact that the movie contains little of Campbell’s text: “So the story of this thriller was actually another surprise to me. By that I mean this movie doesn’t actually follow the original novel, unlike John Carpenters remake which was more faithful.”

It’s futile to argue with an opinion, and if the filmmakers make a film which doesn’t appeal to some of its target audience, then this is the fault of the filmmakers, not the critics. And I can understand most of the grievances mentioned above, even if I don’t feel that what is criticised necessarily works to the film’s detriment. I said earlier that it’s always easy to dismiss modern viewers who don’t appreciate the old style of doing films as ignorant. But to some extent this is the case — not that the critics are ignorant, but simply used to another filmic language and pacing. This is something that — to his credit — Andy Webb at The Movie Scene recognises: “The trouble is that whilst The Thing from Another World is easy to follow and is nicely put together so that there is suspense and some horror it didn’t blow me away. Now in fairness this is something I have often found with popular movies from the 1950s, especially those which are horror and sci-fi movies and have always put it down to not being a huge fan of the genres. […] What this all boils down to is that I can appreciate why for fans of old horror and sci-fi movies The Thing from Another World is a classic. But at the same time for a movie fan with a more general interest in old cinema it is good but not great.”

And of course, to a modern viewer, the Frankensteinean monster isn’t particularly scary, being an obvious man in a suit, and thus those looking for the same kind of thrills and chills as were delivered in Carpenter’s remake will be sorely disappointed. And pointing out that as a shocker this doesn’t work today is honest. There’s always the problem with reviewing old genre films: Does one consider their impact on a modern-day mainstream viewer or the impact it would have had on an audience at the time it was made? I tend to prefer the latter, trying when watching a movie to put myself in the shoes of the audience at the opening night. This is, of course, aided by the fact that I review movies in chronological order, so I have a pretty good idea of audience expectations. And when some critics dismiss The Thing from Another World as “just another alien monster on the loose” film, they disregard the fact that no audience at the time would have seen a single “alien monster on the loose” film, nor really a UFO film — not counting the above mentioned The Man from Planet X — a very different beast, which was released the same year.

When it comes to the reactionary, jingoist politics of the film, I as a European leftist have very little sympathy for it. But I try not to let the politics of a movie influence my analysis of the picture as a work of art or as a piece of entertainment. Birth of a Nation (1915) is still a groundbreaking piece of cinema, despite its horrendous racism. I may not agree with Hawks’ political stance, but I can admire the fact that he made damn good films. But I don’t think (and this may be down to personal taste) that the politics of The Thing from Another World are a great detriment to the film as a piece of entertainment. Yes, there is the oddly lopsided affair with the scientifically minded military and the dogmatic scientists, which does strain credibility somewhat. And this is the main reason I give the film a 9/10 and not a 10/10 score: it tries a bit too hard to cram a story into an ideological mold that doesn’t quite fit, and has to resort to some odd scripting choices along the way.

It’s worth noting that the above cited nay-sayers are only a handful critics out over 100 reviews that I read in researching this movie, most of which give it glowing praise. You go through any book on science fiction films, and they all say the same thing about The Thing from Another World: It is one of the best ever made. Film historian Bill Warren even named his magnum opus, Keep Watching the Skies, after a line in the picture. Warren writes: “It is tense, frightening, amusing, and in every way set new standards for horror and science fiction films. In terms of shock and pace, none came up to its level.”

Hawks & co do almost everything right in this film, and even manage to turn the weaknesses to their advantage. Despite the hokey costume, the Thing set a new template for how sci-fi monsters were supposed to look. Hawks’, Lederer’s and Hecht’s dialogue elevates the film above its B movie roots and brings in a grubby realism from their crime and comedy backgrounds. The banter and the comic relief characters bring a sense of not taking matters too seriously, without ever losing the dark edge of the film – and the action sequences are absolutely beautifully handled. One of the all-time great sci-fi films.

However, I don’t think that the film is without it’s flaws; many of them have been pointed out above. I like The Day the Earth Stood Still, and possibly Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), better. While I’m often a bit prickly when it comes to literary adaptations which get things wrong, I don’t mind the deviations from Campbell’s story — the film is a work that stands on its own legs, and has used the book more as inspiration than as a template. The question that everyone naturally asks of you when discussing The Thing from Another World is whether I like it better than the remake. Well, I personally prefer the remake, but comparisons are ultimately pointless: the two are completely different beasts.

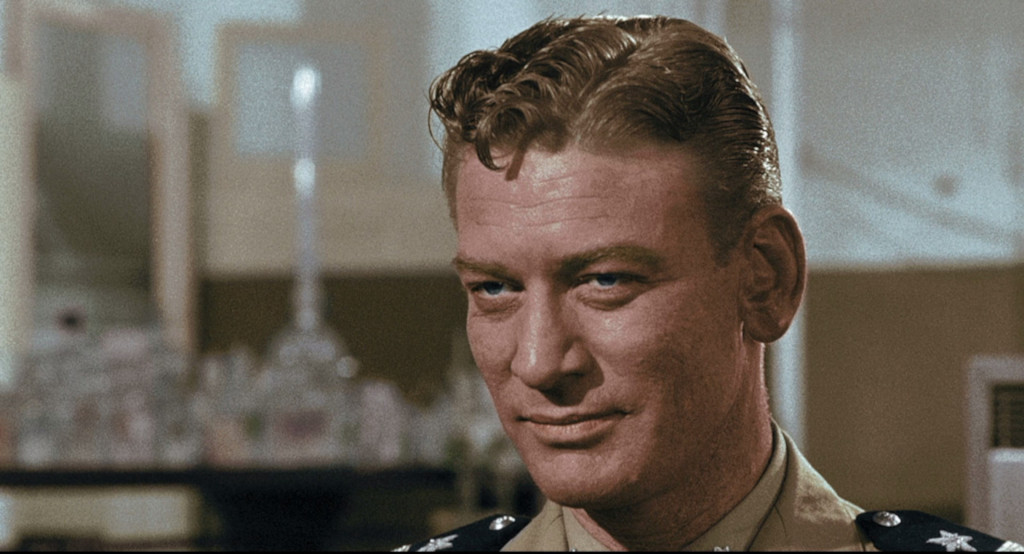

Both Margaret Sheridan and Kenneth Tobey put in very strong performances in the lead roles, perhaps in Tobey’s case the performance of his life, aided hugely by the superb dialogue coaching from Hawks. It is hard to believe this was model-turned actress-to-become-real estate agent Sheridan’s first ever film role, after being snatched up by Hawks, who had extremely high hopes for her career. However, The Thing remains her crowning achievement, as she only appeared in a handful of more films and a few TV series before leaving the movie business in the mid-sixties. According to Hawks, marriage, parenthood and early divorce changed Sheridan, and she ”just wasn’t the same girl anymore”. She appeared in one other sci-fi film, The Diamond, in 1954.

Kenneth Tobey was a theatre actor who made his film debut in 1947 and appeared in mostly uncredited bit-parts or supporting roles. The Thing did launch his career, although he was never quite able to elevate himself from the B movie swamp, and was mostly stuck with supporting roles or playing ”the other man”. He had a major role in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in 1953 (review) , and played the lead in Sam Katzman’s 1955 rip-off It Came from Beneath the Sea (review), and had another major role on The Vampire (1957, review). That same year he produced his own (non-sci-fi) TV series, Whirlybirds, where he played an adventurous helicopter pilot assisting authorities like the police and the fire department on different fantastical missions. The series was a major hit and ran for three years. In the sixties and seventies he concentrated on his Broadway career, and appeared as a guest star on over 100 TV shows, like Perry Mason, Lassie, Bonanza, Gunsmoke, Night Gallery, Kung Fu, Columbo, Starsky and Hutch and Little House on the Prairie.

When the third wave of sci-fi kicked in in Hollywood in the late seventies, The Thing From Another World was rediscovered, and Tobey started getting cameos in films made by filmmakers who had grown up watching the movie in TV reruns, like the Zucker-Abrahams duo that put him in Airplane, and Joe Dante who cast him in The Howling (1981), Gremlins (1984), Innerspace (1987) and Gremlins 2 (1990). A whole new generation found The Thing from Another World in 1982 when John Carpenter made his remake, and Tobey found himself in cameos in sci-fi films like Strange Invaders (1983), Honey I Blew Up the Kid (1992) and Hellraiser: Bloodline (1996). He also appeared in the TV series The Twilight Zone (1986) and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1994). He played a character called Captain Hendry in the fantasy-action cheese-fest The Lost Empire in 1984, and reprised his famous role along Cornthwaite in what was first filmed as a fan film called Attack of the B-Movie Monster in 1984, and was turned into a feature film called The Naked Monster in 2005.

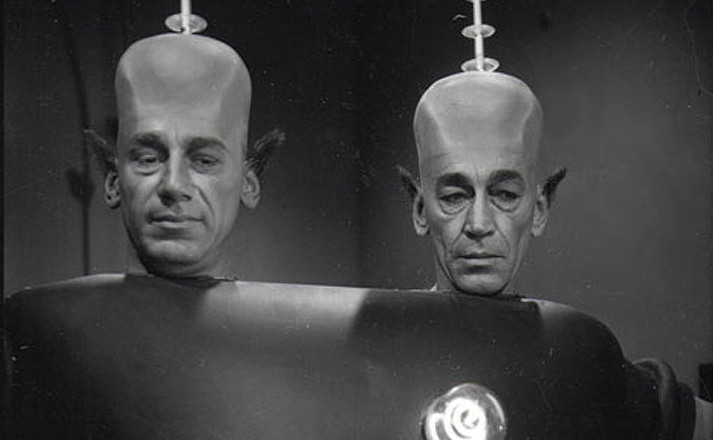

Balding, lanky actor Douglas Spencer, playing the reporter, started his career as a stand-in for film star Ray Milland, and had a number of extra jobs or bit-parts in big and small films in the forties. Scotty in The Thing from Another World is probably his best remembered role, although he did also appear as The Monitor, the big boss baddie in This Island Earth (1955, review) and played the two-headed 1st Martian in the memorable episode Mr. Dingle, the Strong, starring sci-fi series staple Burgess Meredith, in The Twilight Zone (1961).

Theatrical actor Robert ”Bob” Cornthwaite became something of a fixture in sci-fi films, appearing in a number of classic movies, and some not so classic. He often played scientists of authority figures. He appeared in The War of the Worlds (1953, review), Reptilicus (1961), Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), Futureworld (1976), Time Trackers (1989), and reprised his role as Dr. Carrington in the spoof The Naked Monster in 2005 (he actually filmed his part in 1984, along with Kenneth Tobey, but that’s a story for another time). He also appeared in a large number of sci-fi series, including Men Into Space (1959), The Twilight Zone (1963), Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1965), Batman (1966), and The Pretender (1998). Apart from his stage career, he appeared on around 150 TV series in his career.

Small actor Billy Curtis was the star of The Terror of Tiny Town (1938), and featured as one of the Mole-Men in Superman and the Mole-Men (1951, review). He was a robot operator in Gog (1954, review), appeared in The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review), played a Martian in Angry Red Planet (1968) and a child ape in Planet of the Apes (1968).

Tall actor James Arness reportedly hated the role of the monster so much that he refused to show up for the premiere. Arness, of course, would later find everlasting fame for playing the lead in the legendary TV series Gunsmoke, which ran for 20 years on US TV from 1955 to 1975. In the late seventies and eighties he became a huge star in Europe for another series, How the West Was Won. Arness also played the lead in the lost world film Two Lost Worlds (1951, review) and had a major role as Robert Graham in another genre-defining sci-fi film, the first giant insect movie Them! in 1954 (review). Arness was the brother of Peter Graves, a staple leading man in 50’s B science fiction movies, and a star of the TV series Mission: Impossible.

The whole remainder of the cast is at least capable, even if all are not quite top-notch actors, and there’s really not any point in bringing out individual performances, since this is a group effort. Despite some slightly stiff or hammy moments, Hawks’ rehearsals have brought out the best in all involved, and the dynamics of the cast is a joy to watch. Robert Nichols co-starred in This Island Earth and had a number of credited or uncredited bit-parts in other major sci-fi films. William Self appeared in 28 films, but was better known as production manager on series like Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1964-1968), Lost in Space (1965-1968), The Green Hornet (1966-1967), The Time Tunnel (1966-1967), Batman (1966-1968), and Land of the Giants (1968-1969). David McMahon plays Brigadier General Fogarty in Alaska – a brilliantly written little role. Bit-part actor McMahon appeared in small, sometimes uncredited parts in The Day the Earth Stood Still, The War of the Worlds, It Conquered the World (1956, review), The Creature Walks Among Us (1956, review), The Deadly Mantis (1957, review) and The Monster that Challenged the World (1957, review), playing military men in all but two of the films.

Some reviewers claim that Nikki Nicholson was the only woman on the science station – but this is wrong! There are several scenes with a Mrs. Chapman (Sally Creichton), a tall blonde woman who definitely isn’t Margaret Sheridan. Creichton only appeared in three films.

There’s apparently also some visual effects and process photography at work, although I can’t rightly point out where else it would be than the very last creature scene. However, Linwood G. Dunn, the creator of the visual effects, would later work on Star Trek (1966-1969), and was part of the huge special effects team of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Process photographer Harold E. Stine worked on several episodes of Adventures of Superman between 1953 and 1955 and the film Project X (1968).

Janne Wass

The Thing from Another World. 1951, USA. Directed by Christian Nyby and Howards Hawks. Written by Charles Lederer, Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht. Based on the novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell. Starring Kenneth Tobey, Margaret Sheridan, Robert Cornthwaite, Douglas Spencer, James Young, Dewey Martin, Robert Nicholls, William Self, Eduard Franz, Sally Creichton, James Arness, David McMahon. Music: Dimitri Tiomkin. Cinematography: Russell Harlan. Editing: Roland Gross. Art direction: Albert S. D’Agostino, John Hughes. Set decoration: Darrell Silvera, William Stevens. Makeup supervisor: Lee Greenway. Production manager: Walter Daniels. Sound: Phil Brigandi, Clem Portman. Special effects: Donald Steward, Ardell Lytle (pyro). Visual effects: Linwood G. Dunn (special photographic effects), Harold E. Stine (process photography). Stunts: Tom Steele, Billy Curtis, et. al. Produced by Howard Hawks for Winchester Pictures Corporation and RKO Radio Pictures.

Leave a comment