(9/10) Frankenstein (1931) is a masterpiece of camera, light and sound, which proved that sound films didn’t have to be static and clunky. By placing humanity at the film’s core and teasing superb performances out of Boris Karloff and Colin Clive, director James Whale saves it from a creaky script. A seminal piece for SF, horror and films in general.

Frankenstein. 1931, USA. Directed by James Whale. Written by John L. Balderston, Francis Edward Farragoh, Garrett Fort, based on plays by Peggy Webling, & Richard Brinsley Peake, from novel by Mary Shelley. Starring: Colin Clive, Boris Karloff, Mae Clarke, John Boles, Edward van Sloan, Dwight Frye. Produced by Carl Laemmle Jr. Tomatometer: 100 %. IMDb score: 8.0

Tod Browning’s Dracula, released in February 1931 and featuring a Bela Lugosi that would forever be ingrained in our minds as the dark count of the undead, was Universal’s first horror picture in sound. It was also the film that started the golden age of the studio’s horror franchise. But the film that would ultimately define the monster movie genre was Frankenstein, released in November the same year. Together they gave birth to a torrent of horror – and science fiction – films, that has never run dry. Frankenstein was the film that cemented the dark, expressionist gothic style of future American horror films, it was the film that defined the mad scientist, and of course introduced film history’s most recognisable monster in the form of the heavily made-up Boris Karloff. Today it is sometimes overshadowed by director James Whale’s 1935 sequel Bride of Frankenstein (review), that is in many ways a superior film. It is certainly true that Frankenstein is somewhat hampered by some wooden acting, an illogical and seemingly jumbled script and a fairly tight budget. But the beautiful, suspenseful and innovative visual style of Whale, and the multi-layered and ultimately sympathetic portrait that he and Karloff create for the Creature make up for the film’s shortcomings, and it is certainly well deserved of its place among the immortal pieces of art that make up the backbone of much of our cultural heritage. Frankenstein is a very, very good film.

I’m sure I don’t need to tell any reader of Scifist what Frankenstein is. If, by some miracle, you haven’t seen the original film, you still know it by heart through cultural osmosis. So I won’t go over the plot, in any detail. Instead, later in the post, I’ll be taking a long look at the birth and evolution of Frankenstein, and in particular his monster, and how it is that we know him in the visage of Karloff’s shuffling mute, rather than the eloquent, dynamic figure of Shelley’s book. But for now, let’s have a look at the film.

Originally Universal had imagined Frankenstein as a follow-up vehicle for Dracula’s stars, Bela Lugosi, Edward van Sloan and Dwight Frye. But when the intended director, Frenchman Robert Florey was kicked off the project, Bela Lugosi went with him. The new director was British James Whale, who’d been snatched up by Universal after the success of his thoughtful WWI film Journey’s End (1930). Whale was given a pick of around 30 films that were in planning at Universal, if he chose to sign the the studio. He took the bait, and chose, to everyone’s surprise, Frankenstein. According to himself, he picked the story mainly to get as far away as possible from the war films that everyone associated him with. Whale recast the role of the Creature with the then completely unknown British actor Boris Karloff, who was in his forties and was slumming it with extra work and bit-parts. Karloff took an active role in re-shaping the brute monster from Florey’s script, and together with Whale gave it the role of the victim in the film — and gave it a childlike innocence and a sense of tragedy, which is ultimately why he is so memorable — and why the film is such a classic.

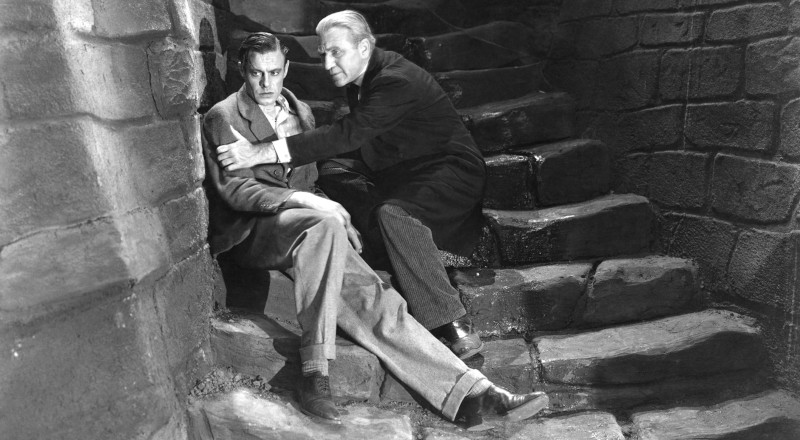

Whale also recast the role of Henry Frankenstein, the med school dropout who starts tinkering with dead bodies he robs from their graves and the gallows. For Frankenstein Whale chose the star from Journey’s End, an intense theatrical actor named Colin Clive, who is another reason for the film’s success. Clive, a theatrically trained actor, had the same sense of tragedy about him as Karloff’s creature, reconnecting with the mirror image motif of Shelley’s novel. In his most manic moments, for example during the creation scene in his Gothic lab, Clive does a performance with the same expressive intensity as German silent actor Conrad Veidt in his unforgettable horror films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) or The Hands of Orlac (1924, review). But like Veidt, Clive also knows when to pull back, and handles the silent moments with equal class, like Frankenstein’s philosophical discussion with Waldman after having brought the creature to life, when he waxes about the scientist as a dreamer, ever hoping to pierce the veil of mystery and discover the secrets of the universe. It’s in these tender moments one sees the other half of the mad scientist, and actually gets an understanding for the man that the film’s female lead Elizabeth (Mae Clarke) is set to marry, and why she has fallen in love with him in the first place — something absent from many of the follow-ups to this film.

Whale inherited the two other stars from Dracula that would become staples in Universal’s horror films; Edward van Sloan and Dwight Frye. Van Sloan had played Professor van Helsing in Dracula, and more or less reprised his role as the all-knowing expert, beautifully rendered with his stiff manner and vaguely European accent. The only real difference between the two roles is that this one is named Dr. Waldman, Henry Frankenstein’s professor. Dwight Frye was one of the joys of Dracula as the possessed fly eater Renfield. In Frankenstein he shoulders the role of the hunchback assistant Fritz, effy about cutting down hanged men from the gallows, but who shows no remorse in torturing the captured creature, that takes its gruesome revenge on his tormentor.

The visual style of the film had already been set by Florey before Whale took over, and since both were huge fans of German expressionism, in particular films like The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1919), The Golem (1916, 1920) and Nosferatu (1922), Whale used many of the designs that Florey had created, and also stuck to some of the camera shots already planned by the previous director. The expressionist legacy is especially well seen in the slanted, off-kilter designs of Frankenstein’s castle, an incredibly tall, narrow set with winding staircases, huge, wooden doors and dark, damp stone masonry, hiding the legendary electrical laboratory designed by Kenneth Strickfaden. Much of the equipment had made its debut in the awful sci-fi musical comedy Just Imagine (review) the year before. Boris Karloff got burned by a spark from the arc generator during the creation scene, and after that refused to go near it. This led to Strickfaden doubling for Karloff as the monster lying on the table in a few shots. The equipment was then used for all Universal’s Frankenstein films, as well as in a number of other horror sci-fi movies. Similar props where later dubbed as ”Strickfadens”.

The opening of the film sets the tone, with a theatrically obvious backdrop for a cemetery, where mourners cry at a funeral. A tracking shot sweeps across the dark cemetery, passing withered trees and a giant, leaning cross, settling on Frankenstein and Fritz in hiding, watching the undertaker fill the grave with dirt. Immediately Whale displays an expressionist, almost surreal style of design, reminiscent of Dr. Caligari, as well as the the macabre subject matter of the film. For movie-goers in the early thirties, this would have been a shocking intro. Whale also immediately shows why he was such a sought after director in the early thirties, with his care-free, mobile camera, as if completely disregarding the big problem of the early sound films, namely the impractical sound recording equipment that rendered so many of the films of the era static and clunky. Compared to the stuffy chamber drama of Dracula, Frankenstein is a feast of dynamism and movement. The lighting of the film is sublime, creating stark contrast, brooding shadows and suspense. The film is cunningly paced, building suspense and momentum. It’s as if Whale would set himself the challenge to make his film just as visually inventive as the last, great silent films. Sound is simply a problem to be overcome, and would not be allowed to interfere with the visual elegance. While German cinematographer Karl Freund did famously innovate with the camera in ways that hadn’t been done on sound films before in Dracula, Whale and his cinematographer Arthur Edeson are light years ahead of Freund and Browning.

Wisely Whale reveals his monster late and gradually. At first it is only a shape under a cloth, and little by little we see a massive body wrapped in bandages – a mystery to marvel at. A naked hand falls out from underneath the covers, nearly frightening Fritz (and presumably the 1931 audience) to death. Colin Clive’s manic energy comes to its right in the superbly edited creation scene, which also highlights one of the strengths of the film that is often forgotten – the sound design. So much emphasis is laid on the visuals, that little has been said about the fact that the film is a festival of sound. It’s easy to forget that the film has no music apart from the opening and end credits. Instead Whale relies on masterful soundscapes – from the crying relatives in the beginning, the thud of the shovel and earth. In the creation scene it’s not only Clive’s hysterical madness and the superb sets and electric flickering that creates a sense of wonder. Our eardrums are filled with noise – the whirring and crackling of the machinery, the mechanical clang of the body of the monster being hoisted to the heavens, the howling of the wind, the sturm und drang of the raging storm – Clive calling out orders, Frye yes mastering back. It’s sublime, masterful. And then the climax, Colin Clive’s triumphant cry: ”It’s alive! It’s alive! Oh in the name of God, now I know what it feels like to BE God!”

As the creature escapes we come to the scene that makes the film. Hunted, despised, living like an animal (to quote the good Mr. Lugosi), the creature suddenly comes across a rustic little house at the lake, where a young girl called Maria (Marilyn Harris), who’s been established in a previous scene, is playing by the water’s edge. In her youthful innocence, she’s nor afraid of the creature, but immediately asks him to join her in her game, as her father Ludwig (Michael Mark) is away celebrating the wedding of Henry Frankenstein and Elizabeth in the town — as Henry believes the creature has disappeared into the wilderness. Karloff’s performance in this scene is sublime, as Maria gives him a flower to smell, and he gently takes her little, pretty hand in his monstrous paw, amazed that such a delicate little thing could exist alongside a hideous thing such as he. The girl throws her flowers in the water, and watches as they float away like little boats, and gives the creature some flowers to make his own little boats. And so he does, with the delight of the almost newborn child that he is. When he is all out of flowers, he picks up little Maria, beautiful as a flower herself, and throws her into the water. When she doesn’t float like a pretty boat, but sinks, he frantically splashes around in the water to save her, and when he can’t find her, and realises what he’s done, he lets out a cry of anguish, and — fear-stricken — runs away.

Whale then cuts to the merriment of the Frankenstein wedding. All the townsfolk are invited by Henry’s father Baron Frankenstein (Frederick Kerr), and the streets are filled with people dancing, drinking and playing music. In a long and bold scene we see Ludwig entering the town, carrying his dead daughter in his arms, on his way to show Frankenstein what his creation has done. Whale juxtaposes the glee of the wedding with the devastated Ludwig, who carries the body of his child through the celebrating crowd. For streets on end Whale follows Ludwig as the wedding guests one by one stop dead in their tracks in bewilderment, and as he passes along the music slowly dies and gives way to silence and shock, then the townspeople join in, making a procession to the Frankenstein house, and when they arrive, celebration has turned into an angry, shouting mob. In the original cut of the film, the part where Karloff actually throws little Marilyn in the water had been cut, as censors thought the murder of a child was too much to show on screen in 1931, and the scene ended where Karloff picks her up. In a way, this only worked to make the reveal of her dead body even more gruesome, as the audience didn’t know what exactly the monster had done to the poor girl. And even without the killing, Whale had guts to hold the audience gaze for such a long time as he did upon the body of a dead child. As one of my favourite Youtube film critics Steve Shives puts it: There’s a lot of silliness in the film, with Boris Karloff running through the woods with bolts in his neck. But moments like the death of Maria and the scene where her father, “grief-strucken, crying, carrying her through the streets, presented without commentary, without embellishment by James Whale’s camera, grounds everything in a very serious emotional reality, and it gives it an emotional weight. And it still holds up today.”

One of the many plot holes of the film if just how and why the creature knew to show up at Frankenstein’s house on his wedding day to try and kill Elizabeth (or rather it’s unclear what his intentions are). This is an instance of how the many changes from book to stage to film over the years have rendered some of the key beats of the story inexplicable. It’s part of the canon that the monster should turn up to kill Frankenstein’s beloved on their wedding day, and in the book the creature gives an eloquent explanation as to why. But in the film, the monster is a mute brute who can neither speak nor read, and by all logic shouldn’t even know where Frankenstein lives, or that he is even getting married. Thus we’re just asked to accept that somehow he’s figured out exactly when and where Frankenstein is getting married — or that it is simply an astounding coincidence that he shows up when he does. But the scene also makes no sense from the point of view of timing. We have all just witnessed the horror and remorse that the creature showed after killing Maria. And the film has established, time after time, that the creature doesn’t kill out of malice. He killed Fritz in self-defence and Maria accidentally. But for some reason, he’s now here for Elizabeth, an innocent woman whom he’s never met in his short, sad life. Sure, one can see the killing of Elizabeth as the creature taking his revenge on Frankenstein — as he does in the novel. But the novel has a clear reason for why he takes his revenge by killing Frankenstein’s beloved one, instead of Frankenstein himself. Again, this is cut from the film because the creature is mute and dumb. In fact, the creature’s animosity toward Frankenstein is even a bit odd in the film, as Frankenstein is, in fact, the only person save Maria that has showed him any sympathy. This sequence is the film’s weakest one, unfortunately a token of the way the story got jumbled up on the long way from book to film, something one can assume that Whale simply didn’t have the time amend.

Anyhow, the creature escapes once again, but is now being chased by all the villagers, with the aid of dogs, as he retreats into the mountains, giving us the long-lived trope of torch-wielding villagers hunting monsters. The chase also introduces the science fiction audience to the Bronson Canyon in Griffith Park, almost literally on the doorstep of Hollywood, which has since been the backdrop for a myriad of sci-fi films. The creature and Frankenstein face off on the top of a mountain, in a fight that’s unevenly matched, to say the least. The creature then escapes the mob, and for some inexplicable reason drags the unconscious Frankenstein with him into a windmill, where they face off yet a second time, before the creature throws his creator off the roof. The mob then burns the windmill in one of the most iconic movie deaths (well, sort of) in history. Such influence has the film had, that even people who know that nothing like this exists in the book, still tend to accept that the creature dies in a burning windmill. Again Karloff sells the scene and delivers an epic death scene that haunts anyone who watches the movie. An unjust death, if there ever was one.

The original script had Henry Frankenstein die at the hands of his creature. And oddly enough, this is the way we imagine both the book and the film ending. It’s even a named trope — when a creation kills its creator, we call it a Frankenstein moment. But that’s not how the book ends, and it’s not how the film ends either. In both instances, Frankenstein survives. However, Peggy Webling’s play that the film is based on, DOES kill Frankenstein in the end. That’s why we get another horror film trope: the replacement love interest. I haven’t mentioned the character of Victor Moritz (John Boles), simply because he is of no consequence to the plot. He simply hangs around the film as the rival for Elizabeth’s hand, and still oddly both Frankenstein’s best friend and seemingly Elizabeth’s best friend as well. And yes, there’s also the odd name switch – in the novel Frankenstein’s name is Victor, and his best friend’s name is Henry. But not Henry Moritz, but Henry Clerval. We’ll get to that later. Of course, this wasn’t the first time this trope was used, as it was a rather common practice in Hollywood films at the time to set up a fall-back option for the leading lady in films where the protagonist dies — the same thing was true for the stage, where this seems to have originated. In fact, the original cut of the film did have Frankenstein die at the windmill. However, this ending didn’t go down well with test audiences, as Colin Clive had created too likeable a mad scientist (as opposed to the novel). A last scene was hastily scripted and shot, which showed Frankenstein’s father exiting Frankenstein’s bedroom, where we see a figure in the background lying on the bed, with a woman beside him. Sipping a glass of wine, Baron Frankenstein lets us understand that the long-awaited wedding would finally take place as soon as his son was up and about. We never see Frankenstein himself, because Colin Clive was already on a ship to Britain at the time the scene was filmed.

The weakest part of the film is without doubt its script. Not so much for the dialogue, which is rather good and actually surprisingly intelligent and even profound at times, and other times very funny. No, the problem is that it was re-written from another script that was adapted from a play that was adapted from another play that was adapted from a third play that bore very little resemblance to the book it was based on, and now someone actually read the book and tried to adapt the text back to its original source, but still keep the film under 70 minutes. There is really no logic or continuity to the thing, and we are never really sure about the time frame. This is most obvious, as stated, around the sequence of the Frankenstein wedding. The film is supposed to all happen during a single night and day, but it feels like too much happens for such a short time frame. The logistics just don’t add up. The scenes are stacked on each other without bridging in between. It’s not that the action is hard to follow, since the story is boiled down to bare simplicity, but it’s feels a bit like we are Star Trek-beaming from one scene to the other.

Apart from the jumbled logistics, there are some inconsistencies and other oddities in the script, mostly plot contrivances. Fritz’ animosity toward the monster is never explained: he helped stitch together the thing, so its monstrous appearance shouldn’t come as a surprise to him. But for the story to work, he has to torment the poor thing so that it can attack and kill him, giving Frankenstein a reason to turn on his creation. And Dr. Waldman insists on restraining the creature even before it has done anything violent. Still, after it has attacked and killed Fritz, and attacked both Waldman and Frankenstein in an attempt to escape, Waldman starts his work with disassembling the thing without any restraints on it whatsoever. Naturally it awakes before the procedure can begin and escapes. And why doesn’t it kill Frankenstein on the mountain when it has the chance? It should be no problem for the creature to snap his neck. Instead he carries the unconscious doctor all the way to a windmill, with a mob on its tail. Why? What is he going to do with Frankenstein in the windmill? Talk to him? He can’t talk! Of course, again, this was apparently the only way the scriptwriters could think of to get Frankenstein into the windmill, the idea here being that the creature doesn’t kill Frankenstein — this leaves us with a situation where the creature doesn’t kill a single person out of malice in the movie, in fact it’s the villagers that kill Frankenstein by setting the windmill on fire, causing the creature to panic and throw Frank from the roof.

Oddly enough, even fans of the book tend to accept most of the changes made for the film, perhaps because most people see the film before they read the book, and the film is such a strong canon in itself. This, despite the fact that apart from the most basic plot, there are very few similarities between the two works. While fans seem to accept the fact that the creature has been made mute, there’s one detail that has raised much ire: the fact that Fritz steals the wrong brain from Waldman’s lab. In the beginning of the film we see Waldman conducting a lecture with two brains in jars (no, he conducts the lecture with a class of students, the brains are props). He tells us that one brain is normal, and the other brain comes from a murderer and serial criminal, and he tells us to observe the marked differences in the texture of the normal brain and the abnormal brain. Then, later, in a famous scene, Fritz sneaks into Waldman’s lab after dark to steal the normal brain. But, suddenly frightened by his own image in a mirror, he drops the jar, and instead takes the one with the abnormal brain. Fans of the franchise tend to take offence with this detail, as it in a way undermines the moral of the story. By inserting the brain of a criminal into the creature, the script sort of wants to give us a reason as to why he turns violent. But that’s not the point, is it? The point is that the creature turns violent because people are being assholes toward him. They call him a monster, burn him with torches, want to disassemble him without proper anaesthesia and hunt him with dogs. Wouldn’t you turn a wee bit violent? Perhaps the “wrong brain” stunt (wonderfully parodied in Young Frankenstein) was a way to explain to give the audience a simple answer to why the creature was dumb and violent, but that’s just underestimating the audiences intelligence. Plus: HOW DID FRANKENSTEIN NOT READ THE LABEL ON THE JAR THAT SAID “ABNORMAL BRAIN”?

The film works so well despite its occasionally sub-par script partly because Mary Shelley’s original story is such a damn good story, and partly because Whale’s film transcends the script. It is such a short, dynamic power punch, that a first time viewer doesn’t have time to ponder the irregularities or the lack of logic in some parts. The visuals are stunning, from the expressionistic design to the suggestive lighting and use of shadows, and the wonderful camera work and editing. Jack Pierce’s makeup is groundbreaking, and the acting is superb.

Apart from the previously mentioned Clive and Karloff, who steal the show, the backup cast is a strong one. Dwight Frye, fresh off his manic performance in Dracula, shows more restraint in his role as Fritz, but still sizzles with crazy energy as the sadistic hunchback. Edward van Sloan’s subdued charisma and precise enunciation make him the steady rock around which the film swirls. Frederick Kerr as Baron Frankenstein huffs and puffs and is the annoying comic relief without actually being annoying, and has a few moments of absolute comic brilliance. He is backed up Lionel Belmore as the burgomaster, another rotund comic relief character. But both of them still seem like they could exist in the real world, and become serious enough when it’s time to hunt down the monster. Here’s the crucial point: they’re not just comic foils, but become real characters living in a real world and react like normal human beings when the script calls for it. This prevents the film from falling into horror comedy territory, like the old dark house movies, where there would often be a main character seemed to be apart from the story, defusing the tension by winking at the audience with remarks like “oh jiminy jeepers, that’s scary!” The characters are funny because they are funny characters in such moments as comedy would be appropriate in real life, not because they crack jokes and wink at the camera all through the film. When shit gets real, nobody in the film is funny (that’s my one problem with Bride of Frankenstein [1935]). Mae Clarke and John Boles don’t have very much to work with in the movie, but they’re both decent actors and do what’s required of them for the film to work.

Aficionados love to heap praise on the acting feat of Boris Karloff, who has rightly been praised for his portrayal of the monster. And it is a boon that it was he and not the Lugosi who got the part. But if truth be said – Karloff is the type of character that clearly shows that you don’t necessarily need to be Laurence Olivier to deliver a stunning performance – sometimes it is enough to be a charismatic actor aided by good direction. What ultimately sets the role apart is that Karloff never plays a monster, rather he plays a victim, and does so with such love and sympathy for the role that it is impossible not to get a bit teary. But in fact James Whale is just as much to be praised for the way he treats the monster and directs the actor, with the aid of Jack Pierce’s make-up, the lighting, the camera angles and the editing.

Colin Clive was chosen by Whale because of his brooding character, high strung, ”pitched for a nervous breakdown”, but with a romantic quality, according to the director. He adds a notion of alienation and bitterness, as mirrored in his creation. Give him a set-piece, a thunderstorm, a motivation and a monologue and he is ”wonderfully, vividly larger than life”, as another reviewer put it. Clive’s performance is notable inasmuch as it definitely cemented the character of the mad scientist – expressive, brooding, haughty and maniacal. But the groundwork and the blueprint had already been laid down by in cinema legend Fritz Lang’s silent sci-fi epic Metropolis (1927, review) by German star actor Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Rotwang, the creator of the film’s memorable android. Whale was a huge fan of Metropolis and Lang.

At this point in my articles I usually go into more detail about the director, lead actors and other important crew members. But this post is long enough as it is, so I’ll put James Whale, Boris Karloff, Colin Clive and Jack Pierce in my pocket and save them for a later date. However, a few short words on some of the other key players:

Carl Laemmle Jr., colloquially known as Junior Laemmle, was the son of German emigre Carl Laemmle, the founder of Universal Studios. Despite Laemmle Junior’s short career (1931-1936) as head of productions at Universal, he is today regarded as a Hollywood legend, primarily for ushering in the golden age of the Universal horror films, starting with Dracula and Frankenstein. He was dethroned in 1936 for spending too much money on unsuccessful films, and never worked in the movie business again.

Robert Florey and Bela Lugosi who were kicked off the project were given Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) as a ”consolation prize”. Despite being only a moderate success, the film is widely seen as one of the more artistically accomplished and thoughtful of Universal’s horror franchise films. Lugosi would, of course, continue his fame in the horror business, and returned to Frankenstein as the deformed Ygor, assistant to Dr. Frankenstein, in Son of Frankenstein (1939, review) and The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) – and would play the monster in the 1943 picture Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (review), when his career had already been in steady decline for a number of years. Lugosi and Karloff would go on to work together in 8 different films. Karloff became hugely successful, while Lugosi was struggling to get by, for a number or reasons. Often it was claimed that he had a hard time getting good roles because of his thick Hungarian accent. But another important factor was that Universal already had their top billing star in Karloff. Lugosi had played Dracula for a very small salary, and continued to work for peanuts, a fact that studios used mercilessly by taking advantage of his poverty. Despite popular belief, Lugosi didn’t hate Karloff, although their relationship was mostly professional, and they were never close friends. He did, in later years as his mental health deteriorated, seem to harbour a deep bitterness about Karloff’s fame and his own misfortune. Just prior to his death he famously hallucinated that Karloff was in his house, and out to kill him. Relatives have stated that during his healthy years Lugosi never said a bad word about Boris Karloff, and respected him both as an actor and as a colleague. Karloff himself often spoke very highly of Lugosi, and lamented the way the studios treated him.

Robert Florey remained a respected director in Hollywood, although never reaching the heights of commercial or critical success as some of his contemporaries. He continued to champion German expressionism in Tinseltown, mostly in B-films, which many critics see as his best work. The first of Universal’s three Edgar Allen Poe adaptations, Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) is often described as an ”American Dr. Caligari”. He is remembered today for the 1937 film Daughter of Shanghai, notable for casting two Asian-American actors in lead roles in time when white actors where still widely used to play Asian characters. The film starred Anna May Wong, Hollywood’s first Asian-American star, and Philip Ahn.

John L. Balderston, who revised Peggy Webling’s play, had earlier worked on the revision of the play that Dracula was based on. He later took up screenwriting, mainly contributing to Universal’s horror films in the early days, but later he worked on high profile films like The Prisoner of Zenda (1937), Gone With the Wind (1939) and Gaslight (1944). He was nominated for an Oscar twice. In sci-fi he is remembered for writing for The Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review), The Man Who Changed His Mind (1936, review), and for his 1932 play Red Planet, that was turned into the film Red Planet Mars in 1952 (review).

Cinematographer Arthur Edeson was a Hollywood legend who worked on silent film classics such as Robin Hood (1922), The Mark of Zorro (1924) and The Lost World (1925, review). He had previously made Waterloo Bridge (1931) with James Whale, and continued to work with him on The Old Dark House (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933, review). He later filmed such legendary films as The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Casablanca (1942). He was nominated for three Oscars, but never won.

Mae Clarke and John Boles had previously worked with Whale on Waterloo Bridge (1931). Clarke had just months earlier created one of the most memorable scenes in cinema, when James Cagney pushed half a grapefruit in her face in Public Enemy. In his AFI acceptance speech, Cagney said: ”Mae, I’m glad we didn’t use the omelet that was called for in an earlier script, as I’m sure you are”. In 1949 she was the female lead in the semi-sci-fi serial King of the Rocket Men.

Edward van Sloan was a theatre actor who played the role of Professor van Helsing in a 1927 stage production of Dracula, opposite Bela Lugosi, and later reprised the role in his second film appearance in 1931 (the first was in 1916). After Frankenstein he appeared in yet another similar role in the Karloff vehicle The Mummy (1932), and continued to play doctors, professors and distinguished, learned men – and occasionally mad scientists – in a string of horror and mystery films. Some of them also touched on sci-fi, such as Air Hawks (1934) and Before I Hang (1940, review, again with Karloff). He had a brief appearance in the 1933 musical sci-fi comedy It’s Great to be Alive, and appeared in two sci-fi serials: The Phantom Creeps (1939) and Captain America (1944, review). He had a small role in the famous disaster film Deluge (1933, review), known for its impressive miniature shots of New York being hit by a tsunami, later recreated in The Day After Tomorrow (2004). In 1936 he was the only actor from the original Dracula film to return to Dracula’s Daughter. In a twist of fate, he ended up working with Robert Florey in the 1935 drama film The Woman in Red. Despite van Sloan’s foreign-sounding name and his distinct intonation and often exaggerated, vaguely European accent, he was born in Minnesota, but did have German ancestry. He appeared in 87 films up until 1950 – including a number of traditional dramas.

Lionel Belmore who plays the puffy burgomaster returned to horror/sci-fi films numerous times in minor or minute roles, among others in Son of Frankenstein (1939) and The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942, review). He did also have a string of roles in more prestigious films. Michael Mark (as Ludwig, Maria’s daughter) is an interesting character as he was used in four of Universal’s Frankenstein films in minor roles – each time a different one, and kept popping up in small roles in 120 films during his career, many of them horror and sci-fi. Interestingly enough, he appeared in three sci-fis during the golden age in the fifties – The Return of the Fly (1953), Phantom from Space (1953, review) and the much lambasted B-film The Wasp Woman (1959).

Frederick Kerr as Henry’s father Baron Frankenstein brings most of the humour to the film as a pompous and oafish unofficial head of the little Swiss town where the film is set. Marilyn Harris is adorable as little Maria. She returns in Bride of Frankenstein. Legend has it that James Whale was not satisfied with the first take of Karloff throwing Harris into the lake. He said that Harris would get anything she liked if she would do the take again. She asked for a dozen hard boiled eggs. Whale provided her with two dozen. Her mother was a bit disappointed in Harris’ meagre wish.

So much has been written about the original Universal Frankenstein film, and it’s been analysed to bits. What I’ll do, is I’ll give the floor to the magnificent Steve Shives, who perfectly sums up my take on the movie : “It is a truly great film, it is a film that has survived all these years and that retains a good deal of its power. […] Whale was just a splendid director. Whale got it in a way that other directors, including Tod Browning, didn’t quite get it, as good as they were, as talented as they were, as dependable as they were at doing what they were doing. Whale understood that not only did these films need to be frightening and gothic and sort of big and imposing and scary, but they needed to have a humanity at their core, they needed to have a sense of tragedy, and they also needed to have a sense of humour. Whale had such a wonderful, dark sense of humour that he brought to his films. It’s there in Frankenstein, it’s really there in Bride of Frankenstein. The last thing you want in a monster movie is a sense of “gravitas”, heaviness, I mean you need to sort of acknowledge the silliness of it in order for it to mean anything.”

The film really is interesting for the fact that as opposed to many similar, later films of the sort, this is a monster movie without an actual villain. Frankenstein, for all his mad scientist antics, creates his creature in the hopes of doing something good, of harnessing the power of life, making the world a better place for showing it that we can conquer death. The creature itself, as we have established, isn’t a villain, but more than anything a victim. Not even the angry mob and the villagers can really be blamed for being a afraid and lashing out at the creature: it looks like a monster, in sounds like a monster and it behaves like a monster. And it has actually killed people. Neither is Waldman, Elizabeth, Victor, or even the oafish Burgomaster a villain. The only one who can be described as villainous is the throw-away character of Fritz — dead within a third of the film. That’s in a way the tragedy of the film version of Frankenstein — with a little better luck things could have gone so very differently. As Shives puts it: “There’s a level of complexity there, that isn’t always there with other horror movies. There are things going on emotionally and thematically in the film, for as big and silly as it is, that give it added depth and added texture, that gives you all these interesting things to notice and to talk about when you see it, that really aren’t present in a lot of other movies, especially other horror movies.”

Frankenstein and Dracula laid the foundation of the Universal horror movie franchise and was the bedrock upon which it all was built. As I’ll go into later, that it was these two stories that together spawned a whole industry was no coincidence — in fact the vampire and the monster have been inseparable from the very beginning. But where Dracula — for all its merits and its success — was a rather creaky and stodgy B-movie, Frankenstein showed that a horror film could be both a crowd-pleasing piece of entertainment and an artistically accomplished work of cinema. To quote Shives once again: “Frankenstein is absolutely outstanding. It’s a film that every film buff and every monster movie lover has to see.”

Frankenstein is not one of those films that were unappreciated in their time but have since become famous, far from it. Not only was it Universal’s top grossing film in 1931 — it was the highest grossing film in the world, raking in a an astounding 12 million dollars. And that’s almost all pure profit, since the movie had a budget of 262 000 dollars. Number two on the list was Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights, which took in a profit of 5 million dollars before subtracting its 1,5 million dollar budget. Thus it isn’t surprising that Frankenstein spawned a plethora of sequels, rip-offs, spin-offs, remakes and imitations, all of which I’ll be reviewing here in due time. I’ll also get into how the Frankenstein mythos changed over time, not only within the Universal framework, but also outside of it, and how it came to influence in particular science fiction. But right now I’d like to continue a bit with the question of how the Frankenstein story, and in particular the creature, or the monster of you like, evolved in the 113 years between the publication of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, or; the Modern Prometheus in 1818 and the 1931 film. How did Shelley’s eloquent, intelligent and philosophical creature turn into the mute, shuffling monster of Whale’s film? I’ll go into more detail on this in a separate post, but if you’re only interested in the general outlines, please keep reading below.

As I’ve noted above, the book and he film bear very little resemblance to one another. Whale sometimes gets the blame for simplifying the story, but as a matter of fact, he brought back some of the nuances of Shelley’s writing that had got lost along the long and winding road from book to 1931 film.

Mary Woolstonecraft Shelley spent her youth among the celebrity stars of the British Romanticism of the early 19th century. Her boyfriend and later husband was the literary wonder Percy Bysshe Shelley, and among their best friends were the even bigger star, the scandal-prone Lord Byron, and John Polidori, author of the first English-language vampire novel, The Vampyre (1819, nearly 80 years before Bram Stoker’s Dracula). Byron and the Shelleys were the Andy Warhols and David Bowies of their day, the Patti Smiths and Robert Mapplethorpes. Instead of hanging out in nightclubs they leased mansions all over Europe, where they would entertain their friends for weeks on end with food, drink, debauchery, music and poetry. And it was, famously, in one of their hideaways in a mansion by Lake Geneva, on a dark and stormy night, that the tale of Victor Frankenstein and his creation was born.

Mary Shelley was the daughter of two noted poets, philosophers and radicals (William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft). She was well educated, curious and a devourer of books. She was also a tragic figure, who defined herself through her many personal losses. The loneliness and alienation of the Creature in Frankenstein can be seen as a metaphor for Shelley’s own feelings. Much like her, he develops a love for literature, art and philosophy. Yes, in the book the ”monster” is a highly intelligent creature with the gift of eloquent speech, prone to citing John Milton’s Paradise Lost. And much like her, he harbours a deep disappointment towards mankind — personified in Victor Frankenstein — that has such talents for extraordinary deeds of love and art, but uses its intelligence for greed, vanity and evil. Much of the book is not action or horror at all, but long philosophical discussions on art, beauty, moral, good and evil, and humanity. It is a complex philosophical and social discussion with multiple layers and ideas – many of which are completely lost or even turned upside-down in later adaptations.

So – how did this multifaceted story about the eloquent and soft-spoken, philosophical, tragic Creature and his neglecting ”father”, mired in his own hubris and pride, turn into the 70 minutes long film about a mad scientist, his hunchbacked assistant Fritz stealing abnormal brains, lightning and electrical storms, IT’S ALIVE, and chaining a mute, lumbering Karloff with electrodes in his neck in a castle dungeon, ending with a religious platitude about ”things men should not interfere with”?

1823 saw the popularity of Frankenstein blow out of proportion with a string of hugely successful theatre adaptations. The first one was Richard Brinsley Peake’s play Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein, which more or less served as a blueprint for most later plays, and just a month later came a play called The Demon of Switzerland by Henry M. Milner, reworked by himself into The Man and the Monster in 1826. These two early plays are in fact seminal for the 1931 film, although they were made over 100 years earlier. In fact, many of the changes that have been attributed to either James Whale or to the writer of the 1927 play that the film is based upon, Peggy Webling, were present already in Presumption, staged in London. Here are some of the changes that Peake made:

- Removal of the complex narrative structure.

- Removal of all backstory for Frankenstein.

- Removal of most of the philosophical discussion.

- Turning Frankenstein from a student of chemistry into a ”mad scientist”.

- Heavy emphasis on the romantic melodrama.

- Making the monster a mute brute.

- The monster is created off-stage.

- The introduction of the exclamatory cry ”It lives! It lives!” (It’s alive! Frank shouts in the film.)

- The introduction of the servant Fritz as a comic relief character.

- The notion that Frankenstein is ”raising the devil” and meddling in God’s business.

- The play ends with both Frankenstein and the monster dying in an avalanche.

- Added songs.

The play does retain some of the story of the family that the monster helps in the book (absent in the film), but combines it with a totally new story of a long lost love of Frankenstein called Agatha. Elizabeth, on the other hand, is turned into Frankenstein’s sister and betrothed to Clerval, rather than Frankenstein’s adopted sister and later wife. The latter change was naturally made as to make he ending of the play a little less gloomy — the Creature doesn’t have to kill off Elizabeth, and can present a happy romance at the end of all things.

Then of course there is the ”why?” Why did the hack writer Richard Brinsley Peake make such huge alterations to the popular story of Frankenstein? There are many reasons. One, of course, is that the novel itself is impossible to make into a straight dramatic adaptation (Kenneth Branagh tried in 1994 with mixed results). Another reason was the fact that the book was widely seen as an attack on religion, or at least as immoral, and the theatre wanted to guard itself against too much criticism from religious circles. But thirdly, and most importantly, this had to do with a rather interesting patent system for dramatic presentation dating back to the 17th century. This stated that only the so-called royal theatres could perform ”legitimate drama”, such as comedies and dramatic tragedies; Shakespeare, Moliere and so forth. The other playhouses were allotted certain genres that were to be performed at certain seasons – these genres were ”illegitimate drama” such as melodrama, burlesque, pantomime, puppet theatre, musical entertainments, and spectacles. The English Opera House, also known as The Lyceum Theatre, where Presumption was performed, had a license to show musical farces and ballad operas during the summer months.

Presumption was a huge hit and immediately gave birth to a number of spin-offs and satires all over London. A more straightforward version was Miller’s The Man and the Monster; or, the Fate of Frankenstein (1926). It is important as far as the film is concerned, as it is the first play to show the awakening of the Creature. The stage direction in the play describes the monster covered by a cloth, as in the film, rising slowly and rigidly, as in many later film adaptations, to meet its maker face to face. It also seems to be the first play to depict the angry mob chasing the monster over the mountains, and it has a scene where the it is captured – also not present in the book, but present in the film. In the end the monster dies by falling into a volcano.

As mentioned, Dracula was the film that kickstarted Universal’s legendary monster movie franchise, but it didn’t come out of nowhere. Universal had a history of “monster” movies from the silent era, most notably those starring the icon Lon Chaney. But more than anything, the precursors to Dracula were the old dark house films, extremely popular in the last years of the silent era. The earliest versions of these films, made in the early twenties, were primarily comedies in which people played hijinks with the protagonist, making him believe he had entered a haunted house. The film that first changed this trope was the often overlooked The Monster (1925, review), made for MGM. While still a comedy, the menace in the movie is real, rather than a put-on. The Monster starred none other than Lon Chaney. The film’s director Roland West followed up this film in 1926 with The Bat for United Artists. Universal followed suit in 1927 with another stage play adaptation, The Cat and the Canary, viewed by many as the ultimate old dark house movie, which was remade in sound as The Cat Creeps in 1930. The old dark house films were successful, but not phenomenally so, and nowhere near as popular as Dracula.

After the success of Dracula, Universal was eager to follow up, and follow up quickly, with another monster movie. As I mentioned earlier, it was no coincidence that Universal followed up Dracula with Frankenstein. In fact, while the source novels were written almost 80 years apart, the vampire and the monster have been intrinsically linked ever since that stormy night at Lake Geneva in 1818. John Polidori, the dentist writer, came up with the hugely influential prose work The Vampyre in that same stay at the mansion in Switzerland as Mary Shelley presented Frankenstein. Polidori’s story clearly influenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula. As early as 1920 it was turned into a stage play in Britain, and staged at the Lyceum Theatre in London. The Vampire, or The Bride of the Isles was a huge success, in part thanks to the performance by lead actor T.P. Cooke. The enormous popularity of the play prompted The Lyceum Theatre and Cooke to adapt another horror story: Frankenstein. Presumption, or; The Fate of Frankenstein opened in 1923, with Cooke playing the creature. Thus T.P. Cooke became the first actor to play both The Vampire and Frankenstein’s Monster, making him something of a 19th century Bela Lugosi.

The person we probably have the most to thank for the fact that Universal made Dracula and Frankenstein in 1931 is Irish stage actor, director, manager, and producer Hamilton Deane, known as a “barn-stormer”. During a four-week period of inactivity due to a particularly nasty case of the flu, in 1923 or 1924, Deane wrote a theatrical adaptation of Dracula, and managed to secure the rights to perform it from Bram Stoker’s widow Florence. The first person to play Dracula on stage was a little-known actor by the stage name of Edmund Blake (real name: Frederick Alkin), and the role was later overtaken by a young Raymond Huntley. Very soon forces were in motion to adapt the play for Broadway. However, Deane’s crudely written text wouldn’t pass muster in New York, so it was arranged to have it rewritten, by none other than the London-based American writer John L. Balderston. And when the finalised play had travelled over the Atlantic, the person chosen to play Dracula on Broadway in 1927 was Bela Lugosi himself. After a succession of actors, Hamilton Deane would finally pick up the vampire’s mantle himself in 1939, adding him to the list if noteworthy Dracula performers.

As the Dracula play had gone down so well, Deane wanted to try his hand at yet another horror adaptation. He hired jeweller and playwright Peggy Webling to write a new adaptation of Shelley’s story. Webling’s story drew primarily on the 1823 adaptation Presumption. By all accounts, it was not a very well-written play, either. It opened in 1927, and actually toured as a double-bill with Dracula, again highlighting the historical connection between the two stories. This time Deane played the monster himself. This play was never staged as such in the US. But after the opening night of Universal’s Dracula in February 1931, when it had become clear that Universal needed to follow up with another horror film, they already had the ear of John L. Balderston, who in turn had the right connections in Britain to track down Hamilton Deane and a copy of Webling’s play. With the prospect of Hollywood royalties, it wasn’t a difficult task to convince her of letting Balderston adapt the play for a film.

So when I say that we have Hamilton Deane to thank for Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein film, I mean that he really was personally responsible for updating these two stories and bringing them into the public eye again.

One key factor for the success of the first Universal monster movies was the casting. It’s impossible today to imagine Dracula without Bela Lugosi and Frankenstein without Boris Karloff. But had Universal had their way, no-one would ever have heard of these actors. The studio already had a horror star: Lon Chaney, who was slated to play the Transylvanian count. Unfortunately Chaney had the bad taste of dying in 1929, and then Dracula went back to the drawing board. Lugosi was touring with the Broadway production of Dracula at the time when the studio was casting the role, but Universal wasn’t interested in the Hungarian with the thick accent. But as Lugosi happened to be in Los Angeles, he marched into Universal Studios and made an earnest case for his casting. Laemmle finally conceded. And the rest is history.

After the success of Dracula, Universal did want Bela Lugosi for their next film. At first he was meant to play Henry Frankenstein, but the slated director Robert Florey ultimately thought they needed someone less intimidating in that role, and offered Lugosi the role as the Monster. The popular version of the story is that Lugosi turned down the role, as he thought it beneath him to play a mute brute. ”I was a star in my country and I will not be a scarecrow over here!” Lugosi is quoted as having said. However, this may to some extent have been a later construction by Lugosi to hide the fact that he was kicked off the film when James Whale came in as director. However, there are numerous records of Lugosi accepting the role (Laemmle even placed ads in trade papers announcing the upcoming Frankenstein film, starring Lugosi), and Florey has claimed that he filmed two reels of test footage with Lugosi in monster makeup before both he and Lugosi were booted off the movie.

According to Mike Segretto at Psychobabble, who has read Florey’s script, it is broadly the same script as appears on screen. The big difference seems to be the characters of Dr. Frankenstein and the Creature. And Florey seems to be to blame for the the absurd and completely unnecessary scene of Fritz stealing the abnormal brain. Under the supervision of James Whale, the script was rewritten by Francis Edward Farragoh and Garrett Fort. Whatever the circumstances, when Whale entered the project, Bela Lugosi exited. For the monster, as we know, Whale chose the 44-year old British actor Boris Karloff (real name: William Henry Pratt), who had slummed around Canada and Hollywood doing extra work and bit parts, and taking odd jobs to make ends meet for over two decades. Karloff immediately started working with Whale to flesh out the character of the monster, as the two agreed on the need for the creature to become sympathetic without losing its menacing edge.

The third link in the creation of Frankenstein was make-up legend Jack Pierce, who created what is now the iconic look of the Frankenstein monster. But how did he end up with this design, and why does Frankenstein look and behave like he does in the film?

Neither Peggy Webling nor James Whale should be thanked nor faulted for turning the creature into a mute. This was simply the standard way in which the Creature had been portrayed even since the very first stage adaptation Presumption in London in 1823. As to why Richard Brinsley Peake turned the monster mute we have no certain knowledge of. But from the point of view of a stage writer imagining how to make a man appear ominous and threatening without the aid of modern makeup effects, lighting and effects, one obvious way would be to turn him into a silent, brooding and mysterious entity. If he opened his mouth and started quoting philosophy, as in the novel, his otherworldly illusion might easily have been shattered, especially as the adaptation was a musical.

Still, the look of the early monster interpretations differ greatly from Karloff’s film version. The first iconic monster came in the form of Thomas Potter “T.P.” Cooke. Promotional images of Presumption show Cooke portraying the monster as a handsome, tall and slender man with long, curly hair, barefoot and dressed in something that looks like a tattered toga. The stage instructions for the play make no mention of the monster being lumbering or stiff. Scholar David Hoehn writes: “The appearance of the Monster in the 1823 production was bizarre, but somewhat more ethereal than hideous. Like the “wretch” described by Frankenstein in the novel, the Creature of the stage version had lengthy black hair. The Monster’s skin was light blue, perhaps to achieve a more striking effect than that which would have been produced by the jaundice described in the novel. The attire of the Monster consisted of a close-fitting cotton tunic and a larger robe or toga that was removed during the performance. The scanty dress of the Monster facilitated stage movement and served to display the physique of the actor chosen to play the role.” So by all accounts, Cooke’s was a physical, agile monster, far from the shuffling creature that Karloff portrayed. However, it seems that the idea of a greenish-blue creature was indeed present from the very first adaptations, while Shelley described the creature as having pale, yellow skin.

A rival production, The Man and the Monster; or, The Fate of Frankenstein in 1826 has a drawing of a Mr. O. Smith as the monster, styled in much the same way as Cooke: with the flowing, long hair of the novel, dressed in a tunic with a belt around the waist. Again, this image of the creature makes him out as a rather handsome creation. An illustration in the Illustrated London News from 1849 shows a very different monster in the play Frankenstein; or, The Model Man from the same year. This time the monster is a broad-shouldered, muscular man, naked save for a kilt-like skirt thingy. The illustrator has drawn him as standing in the shadow, but for all intents and purposes I would say that the illustrator has depicted a black man.

Then, over the years, the image of the Frankenstein creature took on a life of its own. The concept of Frankenstein was heavily used in caricatures and other imagery, often portraying whatever object of ire as a Frankenstein monster, an out-of-control, mindless brute. However, between 1849 and 1927 no actual stage adaptations were created, barring the occasional farce using the Frankenstein theme as a framework. And by 1927, the older musical versions were impossible to heave upon a modern audience. So as flawed as Webling’s play might have been, it was crucial for updating the image of the creature for the 20th century. And here we also return to Hamilton Deane, whose portrayal of the creature seems to have been an intermediate stage between the 19th century image of the monster and the 1931 version. The Guardian, in a somewhat patronising but still wholeheartedly positive review of the play in 1930 wrote: “Mr. Hamilton Deane looks a terrifying figure as the monster. He portrays the character as a mixture of a chimpanzee and Man Friday”.

Deane’s creature is certainly more on the monstrous side than T.P. Cooke’s iconic portrayal. He still wears the longish hair of the novel, but the wig is tattered and dirty, perhaps inspired by the 1910 film version (see below), and his lips painted broadly with dark makeup. As opposed to the light and revealing toga of Cooke, Deane is decked out in a large, heavy overcoat, suggesting a more static and lumbering performance. While still a far cry from the Karloff creature, the 1927 version seems to reveal a progression toward an image of the monster as a slow brute, rather than the agile character played by Cooke, and the makeup also suggest more of a hideous monster than the matinee idol of old.

The 1931 version of the film was not the first movie adaptation. The story had been made into films at least three times before, by the Edison Studios in 1910 (review), starring Charles Ogle, in 1915 as Life Without a Soul and in 1920 in Italy as Il Mostro di Frankenstein. Both latter movies are unfortunately lost, but I have written what I could find out about them here. The Edison Frankenstein, condensed to 12 minutes, has almost nothing in common with the book, and the monster mostly looks like an aged Blackie Lawless who just woke up on someone’s couch after a binge. The second US version, Life Without a Soul, updated the story to 1915, and drew inspiration from The Golem, and now the monster is created from clay with the help of an “elixir of life”. Percy Standing, playing the monster, does so without any elaborate makeup — he’s just basically a big man. Very little is known about the Italian version, but there is a still showing strongman Umberto Guarracino as a bald-headed monster strangling a young woman — again without any visible makeup to make him look monstrous.

The makeup artist for the 1931 film, Jack Pierce, claimed to have studied ”anatomy, surgery, ancient burial rites and decomposition” for three months before designing the monster, starting from drawings made by Whale. The design of the creature was markedly different from the one Bela Lugosi had designed for himself. Production stills show Lugosi in make-up that closely resembles — again — The Golem. Pierce departed from this, and instead created his won distinct design. It was a bold proposition, but he was of the opinion that since the creature was made from different bodies, it should actually look like some horror that had been been stitched together in ill-fitting fashion, something which had never even been attempted before. He reasoned that the design should be crude, as Frankenstein wasn’t a medical doctor. From his medical research he gathered that the simplest way to remove and replace a brain would be to cut the cranium open like a lid, hinge it, replace the brain, and then clamp the head shut. The crude metal clamps gave him the idea of the flat box-like head, which also added height to the monster. The effect was further enhanced by the 5 kg boots that Karloff had to wear. Karloff was actually not especially tall at 180 centimetres – average height.

It was Karloff’s idea to put putty on the eyelids to give the creature a vacant, half-dreaming expression. And by removing a bridge in his mouth, one of his cheeks could be sucked in, creating the hollow look of his face. The make-up techniques that Pierce used were revolutionary, exceeding even the work of Lon Chaney. At the time there was no movie or even stage makeup to be bought in shops, other than your usual face paints and powders. All material had to be created by the makeup artists themselves, and the materials of choice for prosthetic appliances were molten spirit gum and cotton. The makeup was hot when applied and in the case of Frankenstein, took several hours to apply. They only lasted for a single appliance, and once removed were useless, and had to be recreated from scratch again. The process was painful for Karloff, who also received a chronic back injury from the heavy platform shoes he had to wear. More on Karloff and Pierce coming up in later posts.

So one can conclude that the 1931 version of Frankenstein, both in terms of story and in terms of the portrayal of the creature itself, is just as much a “frankensteined” creature as the monster itself, cobbled together from numerous sources over the years, then moulded and refined through the sensibilities of James Whale, Boris Karloff and Jack Pierce. It incorporates tropes that were created by an odd musical version in 1823, and have since become canon, through a number of revisions, parodies and inspired works, such as the muteness of the creature, or Fritz the assistant (mis-remembered in later years as Igor, thanks to the character in Son of Frankenstein). Webling added further details in 1927, for example the scene with the creature and Maria. However, the look of the creature in the 1931 film drew on more contemporary sources, most notably the Golem franchise in Germany, the slow, creepy stiffness of Nosferatu, and quite possibly the iconic performance of Olaf Fonss in the 1916 serial Homunculus. That said, the design of the creature, and Karloff’s performance are unique, in way completely revising the image of Frankenstein and creating for it an iconic look, finally blowing away the memory of T.P. Cooke’s original performance, which had up to that day been the only clear-cut iconography of the monster. While the Frankenstein creature has since been updated and revised many times over, no-one’s been able to overturn the image of Karloff in our mind’s eye when someone says the word “Frankenstein”. Few films leave such a legacy, and this, if nothing else, cements its place among the classics of global cinema.

A shoutout this time goes to Professor Stuart Curran and his team at University of Pennsylvania for the fantastic online resource for Frankenstein trivia, especially Stephen Earl Forry’s comprehensive article on stage adaptations.

EDIT 2022-05-25: A previous version of the text claimed there existed photos of Bela Lugosi in monster makeup. Despite urban legends of such a photo existing, such a thing has never surfaced. Thanks to commenter ferocias for pointing out the error.

Janne Wass

Frankenstein. 1931, USA. Directed by James Whale. Written by Francis Edward Farragoh, Garrett Fort, Robert Florey, John Russell, John L. Balderston, Richard Schayer, based on plays by Peggy Webling, John L. Balderston & Richard Brinsley Peake, based on novel by Mary Shelley. Starring: Colin Clive, Boris Karloff, Mae Clarke, John Boles, Edward van Sloan, Frederick Kerr, Dwight Frye, Lionel Belmore, Marilyn Harris. Cinematography: Arthur Edeson. Editing: Clarence Kolster, Maurice Pivar. Make-up: Jack Pierce. Music: Bernard Kaun, Art direction: Charles D. Hall. Set designer: Herman Rosse. Special effects: Kenneth Strickfaden, John P. Fulton. Produced by Carl Laemmle Jr. for Universal.

Leave a comment