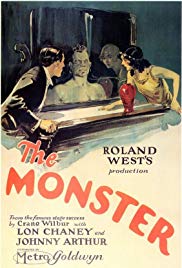

Legendary actor Lon Chaney stars in what may be called the blueprint for old dark house films. This 1925 horror comedy is well filmed by Roland West, and introduced many tropes, like the young couple seeking a phone in a dark mansion after a car accident, the eerie, cowled henchman to the mad scientist, etc. 7/10

The Monster. 1925, USA. Directed by Roland West. Written by Roland West, Willard Mack, Albert Kenyon and C. Gardner Sullivan, based on the play by Crane Wilbur. Starring: Johnny Arthur, Hallam Cooley, Gertrude Olmstead, Lon Chaney. IMDb score: 6.3. Tomatometer: N/A. Metascore: N/A.

The Monster from 1925 is one of those films that movie buffs argue over regarding whether it was the first this or the first that. It has been labelled the first mad scientist film, but that’s simply not the case: the Germans had been doing mad scientists for nearly ten years when this one came out. It’s also been called the first “old dark house film”, but that’s not quite true either: Harold Lloyd’s Haunted Spooks came out in 1920 and Buster Keaton’s The Haunted House in 1921. D.W. Griffith made One Exciting Night in 1922. One can argue that neither of these were really “old dark house films” in the term’s true sense, but they certainly paved the way for The Monster. What one can say with some level of confidence is that The Monster was the first fully-formed example of what would later become known as the old dark house subgenre, and with films like The Monster, The Bat (1926) and its sound remake The Bat Whispers (1930), director Roland West was a key figure in the popularisation of the style.

So first up: what is an old dark house film? Well, it is a particular subgenre of the horror movie that in its purest form combines comedy and horror within the confines of a mysterious, old, dark house. The pure examples of the genre deal with plots reminiscent of mystery novels, often boiling down to a whodunnit, a howdunnit or a “had-I-but-known” drama. A peculiarity of the old dark house film is that it tends to insert comedy into the horror trappings, to a lesser or greater degree, without necessarily turning into a spoof. A successful example of the style manages strike a balance where the fast-paced energy of slapstick comedy melds with the eerie atmosphere of the horror genre without cancelling it out. The golden age of the old dark house film was the mid-twenties to the early thirties, and critics argue whether its prime example is Paul Leni’s The Cat and the Canary (1927) or James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), which sort of retroactively gave the style its name.

Old dark house films generally tend to shy away from science fiction elements, or to use them as minor McGuffins. More often these stories deal with seemingly supernatural events that turn out to have perfectly natural explanations. This is also the case with The Monster, which can’t really be called a science fiction film, but rather a horror comedy with a slight whiff of sci-fi.

The film sees a trio of unlikely heroes investigate strange disappearances around a closed-down insane asylum, only to fall prey to its current master in the shape of horror legend Lon Chaney Sr. A big farmer in the small town of Danburgh has gone missing, and his car is found empty on the road, and neither the local law officer (Charles Sellon) nor the insurance detective (William H. Turner) believe it to be anything more than a car accident. However, the local general store’s stock boy and wannabe-detective Johnny Goodlittle (Johnny Arthur) finds clues that Dr. Edward’s sanatorium is somehow involved. Nonsense, say the lawmen, everyone knows that Dr. Edwards has left for Europe two years ago and the asylum is closed.

Making no headway on the case, Johnny instead focuses his energies on wooing the store owner’s daughter Betty (Gertrude Olmstead). Unfortunately his attempts are thwarted by the local dandy, Johnny’s superior clerk at the store, Amos (Hallam Cooley). But he has some cause for celebration, as he finally receives his mail-order detective’s diploma, complete with cuffs, a sheriff’s star and a revolver. One evening the three meet up at an evening ball, and after Amos sweeps Betty away from Johnny, the newly-baked detective takes a stroll outside and comes across a strange man who behaves almost like he escaped from a mental asylum. Through the stormy night Johnny follows the man, later revealed to go by the moniker Daffy Dan (Knute Erickson) to the old not-quite-closed asylum. At a turn in the road he observes a sinister, hooded figure (Rigo, we learn later) lowering an obstacle onto the road, just in time or Amos and Betty to hit it with their car. Johnny is captured by Rigo and Daffy Dan as he tries to help and is taken inside the asylum. Amos and Betty are quite alright, and believe they just met with an ordinary accident. Wet and cold, they see a light over at the Frankenstein place, so they decide to head over to the asylum to see if anyone is at home, and if they could use their phone, seeing as they are both in a bit of a hurry.

Here they are greeted by two strange butlers, the hooded Rigo (Frank Austin) and the gigantic Nubian Caliban (Walter James in blackface), and after a while the sinister Dr. Ziska (Lon Chaney) appears, and from then on, the film becomes a classic old dark house film. There are creaking doors that slowly open and close by themselves, metal plates that slam down when windows are broken, secret trap doors, groping hands appearing from behind curtains and and from under beds, evil henchmen hypnotically controlled by their master, thunder and lightning, escape attempts over rooftops, as well as a secret lab with a Death Chair and a dissection slab.

The Monster isn’t really a supernatural horror story, neither is it really a science fiction film, as the sci-fi elements are only alluded to but never put into action. The MacGuffin of the movie is a death chair, modelled on the electric chair, with which the mad scientist is going to transfer Amos’ soul into Betty’s body, in order to “discover the secret of life” (this is, thankfully, not elaborated on …). This, however, isn’t revealed until the film’s final moments, and our heroes’ motivation is to 1) find out what has happened to the lost people and 2) find a way out of the house, with the latter motive quickly taking over the first as they discover that their own lives are in peril.

The movie has a bit of a sketchy reputation, and it is not without its problems. Even though it starts with a dramatic car crash, it takes it sweet time to get going, as the characters are first introduced in an over-explaining fashion, Johnny’s quirks, such as his always checking the detective guide-book in order to make a decision, have to be established, as must the romantic rivalry. During the first third it does tread water a bit. Many of the shots are also unnecessarily long: we sometimes get up to ten seconds where nothing happens, except we see a door opening or closing very slowly. The plot itself is a bit meandering and plodding, but does pick up steam in the third act.

What strikes me, though, when I watch the movie is how familiar it all seems. In fact it strikes me that this film is more or less the blueprint for the much-parodied old dark house genre. This is the film that introduced cliche of a young couple’s car breaking down and them having to search for help at a nearby scary house. It has since been used in countless films and TV series. The plot for Ed Wood’s Bride of the Monster (1955, review) is more or less directly lifted from The Monster, and it was beautifully parodied in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975).

The common thread in all the haunted house horror comedies of the early twenties is that that the supposedly haunted house isn’t really haunted, and more often than not, it’s simply actors running around with sheets over their heads. In Harold Lloyd’s short film Haunted Spooks (1920) and Alfred E. Green’s The Ghost Breaker (1922) it’s a rival to a heiress’ hand that plays tricks on a suitor and in the short film The Haunted House (1921) it’s a theatre company playing a prank on Buster Keaton. All these three are very high on comedy and very low on horror. D.W. Griffith’s One Exciting Night is more of a traditional mystery drama in the vein of Agatha Christie (actually inspired by another author, more on that later), where a gathering of people at a party in a mansion try to figure out the identity of a murderer. A precursor to these horror comedy movies was Cecil B. DeMille’s original version of The Ghost Breaker, released as early as 1914.

What sets The Monster apart is that it is actually creepy at times, and when it goes for scares, it doesn’t punctuate them with comic reliefs. While Johnny Arthur plays the type of effeminate doof that he is remembered for (if he is remembered), he is an actual character invested in the story, and not just a simpleton who’s afraid of jump scares, like the comic relief characters in many similar films. Johnny Goodlittle has an actual character arc, as he has to find his hero inside and save his friends from the clutches of the mad Dr. Ziska. The Monster is also the first of the old dark house movies to include a mad scientist, the creepy servants and Ziska as the Dracula-esque host of the mansion.

It’s often presumptuous to claim that such-and-such a film gave birth to this or that trope, and we tend to overstate the importance of “firsts”. More often than not, there are workings behind the scenes that shape the medium of film in ways that even the brightest film scholars fail to comprehend. That said, it is hard not to view The Monster without noticing the many similarities to later films, as described above, and argue that this film really is the first one where the many disparate elements have been put together in a way that has since become iconic, even cliched. From the dark, rainy night with its young, accident-stricken couple who seek a telephone in an old dark house to the way that Lon Chaney portrays the sinister master of the “haunted house”. It’s startling, on viewing, to see just how similar Chaney’s portrayal of Dr. Ziska is to Bela Lugosi’s in Dracula (1930). Just like Lugosi five years later, Chaney plays his antagonist with slow, stiff authority, alternating between a sinister, over-polite smile and expressive bursts of anger and resentment. Chaney even uses the claw-like hand gesture that became such a calling-card for Lugosi when Ziska is controlling Rigo telepathically. Now, I’m not saying that Lugosi ripped off Chaney, because, as stated, there are many variables that we just don’t know in retrospect, but as an isolated incident The Monster does seemingly predate so many of the later horror tropes that it’s impossible not to give it some credit for shaping the future of horror films.

But we should also consider the rich cultural tapestry against which The Monster was made. The script itself is based on a 1922 Broadway play with the same name as the film by writer, director and actor Crane Wilbur, who was actually one of the bigger stars of the early American movie scene, best known perhaps for his role as the male protagonist in the genre-defining serial film The Perils of Pauline (1914, see my article of the death ray serials for more info). Wilbur’s career deserves a book, and I’ll get back to him later, but for now, let’s be content with noting that he was one of the many stage writers and directors immersed in the old dark house genre on Broadway in the early twenties.

As stated earlier, the old dark house genre was a mash-up of the mystery thriller, the gothic novel and vaudevillian situation comedy, with an emphasis on the story structure created by the mystery novel. Now, the mystery novel, or detective novel, was established as a genre in the mid-nineteenth century, partly as a response to the English renaissance, whereas the human capacity for deduction and intelligence was explored, and partly due to the fact that the police force was institutionalised during the industrial urbanisation. With the birth of the actual police detective came the fictional detective novel. E.T.A. Hoffman’s Das Fraulein von Scuderi (1819) is quoted as a very early example, but it is Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) that is commonly cited as the first mystery story. Two very popular novels were Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868). The genre really exploded in 1887 when Arthur Conan Doyle created the character of Sherlock Holmes. After this, hundreds if not thousands of mystery stories appeared both serialised and short for in magazines and pulps, as stand-alone novels and as stage plays, often borrowing or blatantly ripping each other off.

One of the defining works of the genre that would become known as the “had-I-but-known” genre, which is closely related to the old dark house genre, was the novel The Circular Staircase published in 1908, written by American author Mary Roberts Rinehart — note that this was almost 15 years before Agatha Christie had published her first novel. The book follows a female protagonist trying to to solve the puzzle of a series of mysterious disappearances in an old mansion. Perhaps inspired by the story was the 1909 stage play The Ghost Breaker written by Paul Dickey and Charles W. Goddard, on which DeMille’s 1914 film was based, and it follows a protagonist who is foiled by rival suitor who tries to scare him and his fiancée away from an old house, by making it seem haunted, in order to lay his hands on an inheritance. And in 1920 there was a development almost as important as that of the emergence of Sherlock Holmes, namely the emergence of another detective by the name of Hercule Poirot, in Agatha Christie’s first published novel The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

1920 was also an important year for the old dark house genre on stage, as it saw the opening of the play The Bat, which may very well be the most important of all works for the crystallisation of the genre. The play was co-written by none other than Mary Roberts Reinhart and was, in fact, an adaptation of her afore-mentioned novel The Circular Staircase. However, the story was radically re-written, and most importantly the play added the titular villain, a mysterious and looming presence stalking the mansion in which the mystery takes place. The play was a resounding success, both critically and commercially, and was performed over 800 times both in New York and London, and was almost single-handedly responsible for the boom of mystery and old dark house plays that emerged in the twenties. It was quickly followed by the three plays that, along with The Bat and The Ghost Breaker make up the canon of the old dark house stage repertoire: Crane Wilbur’s The Monster, John Willard’s The Cat and the Canary (1922) and Ralph Spence’s The Gorilla (1925).

Another play, which leans heavily on tropes and themes prevalent in the old dark house plays opened in London in 1924: Hamilton Deane’s Dracula, based perhaps even more on the popular mystery plays than on Bram Stoker’s original 1897 novel. It was re-written by John L. Balderston for Broadway in 1927, where it starred a certain Bela Lugosi. This interest in the macabre also inspired a new stage adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, written in 1927 by British playwright Peggy Webling, which was also adapted by John L. Balderston for the US market, and which eventually served as the starting point for the screenplay for Universal’s Frankenstein (1931). The film has rather little to do with mystery novels or old dark house productions, but it is probably safe to say that it wouldn’t have been made without the huge interest in mystery plays that gave birth to Universal’s first horror film with sound, Dracula. And its depictions of Frankenstein’s lab does bear some clear resemblance to Dr. Ziska’s ditto in The Monster. Chaney would also without doubt have been the first choice to play the Frankenstein creature, had he not tragically died in 1930, on the cusp of starring in Dracula.

Master director D.W. Griffith actually tried to secure the movie rights to Reinhart’s The Bat, but couldn’t, so instead he made One Exciting Night, which was a clear ripoff. Instead The Bat was adapted for the screen in 1926 by none other than Roland West, the director of The Monster, who also made a sound version of the film, The Bat Whispers, in 1930. As stated earlier, Paul Leni made the terrific The Cat and the Canary in 1927, and in 1932 Frankenstein director James Whale topped the genre off with The Old Dark House, which must be seen as the last and perhaps best addition to the original old dark house craze, before monster movies became all the rage instead. The film had a mind-boggling cast of Boris Karloff, Gloria Stuart, Charles Laughton, Ernest Thesiger, Melvyn Douglas, Lilian Bond and Raymond Massey. A monster mash if there ever was one.

So there you have it, a pretty comprehensive timeline of the old dark house genre. The Monster wasn’t the first film in this style, but it does have more in common with the later The Bat and The Cat and the Canary than with Ghost Breakers or Haunted Spooks, simply because it takes its horror elements seriously.

But is it a good film? The short answer is: yes. From a strict cinematographic point of view The Monster is a well-made film. Compared to much of the dregg that was churned out by the American film industry at the time, The Monster is a great film. Roland West was no Griffith or DeMille, but he was always a kinetic director. While the idea of an actual moving camera was still almost unheard of in the US at the time, and almost all shots in The Monster are static, West shoots his scenes from a surprising number of angles, often switching between wide, mid and close shots. Some thanks to this must certainly go to master cinematographer Hal Mohr, who would go on to win two Oscars further down his career, for his work on William Dieterle’s and Max Reinhart’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) and the 1943 remake of The Phantom of the Opera. Mohr and West borrow their lighting schemes from German Expressionism, and do so very well, showing more care and attention for the lighting than most of the mystery film makers at the time. And despite the fact that the film drags in places, the editing is, for the most part, outstanding. Nominal editor A. Carle Palm only has a handful of film credits to his name, so one must assume that West was primarily in charge of the editing, which is dynamic and (for the time) fast-paced. Kudos should also be given to art director W.L. Heywood, who creates a well-rounded and suitably eerie haunted house. Furthermore, the action is very well filmed and the stunts beautifully executed.

So, technically and artistically The Monster is a good film. This should not come as a surprise, as it was produced by the newly founded Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer company, perhaps the biggest player in Hollywood at the time, and filmed at the legendary MGM Studios (now Sony Pictures Studios) in Culver City just outside of Hollywood. Still, it is a film that is often derided. And that is something that probably comes down to matters of taste, more than anything else. Some people feel that the horror story is ruined by the comedy. And sure enough, if you don’t like horror comedies, then you won’t like The Monster. I am still ambiguous about them, even if I have slowly learned to appreciate horror comedies for what they are. And even if you like horror comedies, you perhaps don’t like the particular type of comedy that Johnny Arthur brings to the table, and in that case, again, you won’t like the film. I actually think that Arthur is rather good, even if some of the gags, such as him being drunk and carrying around a jug ow wine everywhere, go on for a bit too long. Then there are those who feel that Lon Chaney is miscast in the role of Dr. Ziska for one reason or the other. I suppose that’s also a matter of opinion, but I would argue that it’s also a matter of expectation. Chaney was top-billed thanks to his fame, but doesn’t actually have that much screen time, and when he is on screen, he gives a performance that is at the same time restrained and wonderfully hammy, just as was Lugosi’s in Dracula. Some have suggested that Chaney didn’t really understand what kind of film he was in, but that’s just an insult to the man. Chaney plays his role seemingly straight-faced, but his hammy delivery creates a sort of caricature of the character, which is probably exactly what Chaney had in mind. He certainly wasn’t above making fun of his horror roles.

The star of the film isn’t Lon Chaney, but he was certainly the draw. Readers of this blog probably don’t need any introduction to Chaney, the man’s a legend. By 1925 Chaney was among an exclusive handful of superstars of the US film scene, rivalled in popularity only by actors such as Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, John Barrymore, Douglas Fairbanks and Rudolph Valentino. The Monster was sandwiched in between four of his most important movies, Wallace Worlsey’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), Victor Sjöström’s He Who Gets Slapped (1924), Rupert Julian’s The Phantom of the Opera (1925) and Tod Browning’s The Unholy Three (1925). He was on the absolute top of his career, creatively and commercially, and after 1925 he would work exclusively for MGM, despite the fact that his biggest hit, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, was produced by Universal, laying the foundations for the studio’s monster franchise. Between 1925 and Chaney’s untimely death from lung cancer in 1930 he made around two dozen more films, including Tell It to the Marines (1926), which earned him an honorary membership of the US marine corps, and which was the film that he himself was most proud of, Tod Browning’s The Unknown (1927), this time without arms, Tod Browning’s West of Zanzibar (1928), one of his most understated and best performances, and the fabled lost film London After Midnight, again directed by Tod Browning.

Chaney is, of course, known as “the man of a thousand faces”, one of the first make-up geniuses in Hollywood, which made him the natural pick for roles which required great physical transformations, such as cripples, deformed people or monsters. While he is best known for his monstrous roles, such as Quasimodo and the phantom of the opera, his range was much broader than that, and it was the acting chops he brought to these roles that made them so memorable, not the make-up alone. In fact, the large majority of his roles were in in dramas and melodramas, and it was in his more understated work toward the end of his career that he arguably did his best work.

His background was in theatre and vaudeville, and he was a talented dancer and singer, but was pushed away from theatre circles and into film in the film industry after his wife’s suicide attempt in 1913. After struggling for a few years at Universal as a character actor he went freelance, and made his name in George Loane Tucker’s The Miracle Man (1918), where he played a contortionist, giving proof of another one of his many talents. Chaney’s ability to contort and control his body was one he used in a number of movies, as he played people without arms or legs, paralysed characters or people with one deformity or the other. One of my favourite Chaney films is The Penalty from 1920, in which he plays a criminal mastermind whose legs are amputated from the knees down. For the effect, Chaney tied his legs to his back and had to walk on his knees throughout the movie. The harness was so painful that he could only use it for ten minutes at a time, and it permanently damaged his leg muscles. But the illusion in the film is seamless.

Chaney is best known for being the first monster maker of Hollywood. As we all know, he created all his own make-up, his harnesses and other odds and ends for his characters. This was as much a choice of his as it was a necessity. To understand why this was such a big deal for film producers and directors, one must be aware of the fact that movie makeup was a non-existent trade in the early days of film. Films did not have makeup departments or make-up artists. Some stars would have their own makeup artists on set to make them look pretty, but that that was about it. All actors had to do their own makeup, and all they had to fall back on was theatre makeup, which didn’t necessarily look good in close-ups under the bright studio lights. And that’s why some of the makeup of early horror films (see for example the early Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde movies) looks so awful. Any actor who could convincingly do elaborate makeups was guaranteed work in the movies.

This did not mean that any actor with the same makeup skills could reach the same heights as Chaney. Case in point is another young character actor struggling for parts around the same time as Chaney in Hollywood: Jack Pierce. Between around 1915 and 1930 Pierce struggled as an extra and character actor with a knack for makeup, but was never able to move on to bigger roles. He was more valued for his makeup skills than for his acting, and eventually became the head of Universal’s makeup department, and the rest is history. Chaney was that rare breed of artists who were able to elevate his character actor work from the background to stardom, much like a later Charles Laughton or Anthony Hopkins. He had an uncanny ability of bringing life and soul to roles, even through thick layers of makeup. While The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera are remembered for their makeup, the reason we keep coming back to them is Chaney’s tremendous acting, as he brings real human tragedy, passion and fire to his characters behind the makeup. In this sense, the closest equivalent today would probably be Andy Serkis.

But as stated, the lead role in the film is actually Johnny Goodlittle, played by comedic actor Johnny Arthur. Arthur is almost completely forgotten today, and some have even gone as far as saying he should be counted among the silent eras physical comedy greats such as Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. This is a bit revisionist, though, since Arthur never commanded the same box-office pull as those two greats, and his leading man roles were very few and far between. His trademark character was an effeminate, swishy man, a fussy office clerked or a pecked husband, and not seldom an implied gay man. In later years he has gotten some credit for being the actor who first regularly played gay men in films. It was also perhaps because of this fact that his work was seldom brought up during the days of the Hays code, contributing to his obscurity. Nevertheless, the fact is that for most of his career he played bit-parts, even if in successful films such as The Desert Song (1929), Penrod and Sam (1931) and The Ghost Walks (1934).

It was Roland West who gave Arthur his first movie break in 1923, with a substantial role in the now lost science fiction movie The Unknown Purple, a film in which an inventor, upon his release from prison, invents a ray which turns himself invisible in order to exact revenge on his unfaithful wife and her crooked business partner. The Monster was his second movie role, and one of his few, if not his only, romantic lead. He is probably best remembered today for his roles in The Monster, as the father in a number of Our Gang shorts, and as the Japanese villain in the 1943 serial The Masked Marvel. He passed away in relative obscurity in 1951, unmarried, childless and living on welfare, and his burial was paid for by a Hollywood charity. His grave was unmarked for decades, until a group of fans arranged for a headstone in 2012.

Johnny Arthur’s style of comedy is sort of what you’d get if you’d cross Stan Laurel with Rick Moranis and throw in a bit of Jim Parsons. It’s the kind of child-friendly comedy that my grandmother would approve of, but with a bit of adult innuendo that she’d secretly find just raunchy enough for her taste. His character in The Monster is the socially awkward geek who dreams of becoming a man’s man in order to conquer the hand of his boss’s daughter. But instead of actually, so to speak, “manning up”, he does a mail-order course in how to be a detective, and jumps around giddy as a schoolboy when his diploma and revolver arrive. He is constantly thwarted in his romantic adventures by the local Don Juan, and is too timid to do anything about it. When danger looms, he would rather refer to his detective’s guidebook than actually putting himself in harm’s way. However, when the love of his life is threatened, he falls back on his romantic notions of chivalry, ready to instantly sacrifice himself instead of thinking for a moment in order to figure out a solution where both survive …

Some viewers of The Monster have pointed out that the character of Johnnie Goodlittle is more or less a ripoff of Buster Keaton’s ditto in Sherlock, Jr. (1924). And they are absolutely right. Fritzi Kramer of the otherwise always superb blog Movies Silently regards this as a fallacy, as the play The Monster was written before Sherlock, Jr. But according to plot outlines of the original play, Arthur’s character actually doesn’t exist in the play, as such. The lead in the play is a reporter investigating the disappearances at a mansion where the mad scientist Ziska lives with his servant Caliban. The love interest in the play is simply a random prisoner in the mansion. The apparent comedic character is a tramp who has also been brought to the house, and turns out to be an undercover police officer. So the whole mail order detective shtick is completely borrowed from Sherlock, Jr. West and Arthur seem to be going for a Buster Keaton-type of comedy in the movie, and in my opinion do it surprisingly well. There’s a very good bout of physical comedy at one point in the film, where Arthur does a wire-walking stunt (it may be a stunt double in the wide shots) and slides down a staircase hand-rail only explode out of the front door in a great chase sequence that could almost be taken directly from a Buster Keaton film. But the best comedy is actually in the title cards, and it’s a bit surprising that The Monster was never remade as a talkie. This would have been just the sort of thing that Bob Hope could have shone in.

There’s an interesting plot twist that isn’t mentioned in any synopses of the play, so I’ll assume that it’s an addition by screenwriters West and Willard Mack. At one point in the film it is revealed that Dr. Ziska and his handymen are in fact inmates of the asylum (the play doesn’t seem to be set in an asylum), and the actual doctors and staff have not in fact gone to Europe, but are imprisoned in the basement. This is a clear nod to Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether (1845), and to my knowledge the first time this trope has been used in a film, unless you count the allusion to the reversed roles of madman and doctor in the twist ending of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920).

All in all, the setting and most of the characters of the play seem to have been changed for the film. The play seems, to all intents and purposes, to be much more of a classic old dark house film with an eerie mansion and a handsome hero who investigates a mystery, in the spirit of the times he is a reporter. Without having read the play, the changes seem to be for the better. The love triangle between the three people involved in the general store creates more tension and drama, and provides ample opportunity for comedy, as opposed to having three strangers randomly converge at the mansion. Setting the story in an asylum was, at the time, a fresh twist on the old dark mansion that had been the setting for oh so many stories in literature and on stage already (granted, there’s nothing in the actual sets of the film that suggests a mental asylum, it might just as well have been any old mansion).

As stated earlier, playwright Crane Wilbur’s career deserves a book. He rose to prominence on Broadway as an actor as early as 1903, when he made his stage debut, and transitioned into film in 1910. He made his name as the male lead in the immensely popular serial The Perils of Pauline (1914) opposite action heroine Pearl White, who went in to become the queen of the early US serials. He then made his name as a writer and director on Broadway, writing seven plays between 1920 and 1934, including The Ouija Board (1920) and The Monster (1922). He acted in several revivals of his plays, and in other first-rate productions, like A Farewell to Arms (1930) and Mourning Becomes Electra (1932).

Wilbur directed a handful of movies in the silent era, but after honing his directorial craft on stage, he returned to film direction with a vengeance in 1934, when he co-wrote and directed the highly controversial Tomorrow’s Children, in which he exposed the tragedies behind the politics of eugenics. So poignant was the movie that it was banned in New York as morally corrupting and “inciting to crime”, as it spread information about birth control, which was illegal at the time. The film followed a married couple who fight the threat of forced sterilisation. He then went on to direct another 30 films up to 1962, including his own modernised version of The Bat (1959), starring Vincent Price.

He is best known, however, for his work as a screenwriter. Apart from films which are based on his plays, he wrote or co-wrote the screenplays for some 60 films during his career, predominantly mystery thrillers, and a number of short propaganda and instruction films during WWII. Many of his films had lewd and raunchy female criminals and villains, and Wilbur seems to have had a thing for prisons and other confined settings such as hospitals and reform schools. Some of his films include Crime School (1938) starring The Dead End Kids and Humphey Bogart in his pre-fame years, The Patient in Room 18 (1938), Girls on Probation (1938), with Ronald Reagan as the male lead, Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison (1951), which inspired Johnny Cash to write Folsom Prison Blues and Women’s Prison (1955) starring Ida Lupino and Jan Sterling, as well as House of Women (1962), his last film.

Crane Wilbur’s best known crime drama is probably André de Toth’s Crime Wave (1953). Still, he is most famous for his horror and mystery movies, which include the Boris Karloff vehicle The Invisible Menace (1938), The Amazing Mr. X, starring Turhan Bey, and most of all two horror classics starring Vincent Price, House of Wax (1953) and The Mad Magician (1954). He also worked on the screenplay for the 1961 (loose) adaptation of Jules Verne’s Mysterious Island with stop-motion monsters animated by Ray Harryhausen. In 1959 he wrote the screenplay for a rare biblical adaptation, the hugely successful epic Solomon and Sheba, directed by King Vidor. Wilbur‘s re-interpretation of The Bat has since become the most successful adaptation of author Mary Roberts Rinehart’s work, grossing Allied Artists over nine million dollars, a fantastic amount of money at the time. Throughout his career Wilbur made films that championed liberal ideas, such as the abolition of capital punishment and forced sterilisation, and often called attention to the mistreatment of prison inmates and called for greater efforts for their rehabilitation into society.

The third co-writer Willard Mack had a similar career trajectory as Crane Wilbur. Canadian-born Mack (Charles Willard MacLaughlin) entered the entertainment world as an actor, eventually on Broadway, where he also started writing, producing and directing his own plays. Of his stage productions the best known is probably The Noose (1926), as it featured a young chorus girl called Ruby Stevens, whom Mack had cast in a supporting role, as wanted it to be played by a real chorus girl. After realising her potential, Mack re-wrote her part to make it much bigger, coached her acting and suggested she adopt the stage name Barbara Stanwyck. And the rest, as they say, is history.

During his Broadway years Mack also started to write for the movies, and often appeared in films as an actor between 1910 and 1920, and eventually directed four features, which remain his best known work for the screen, The Voice of the City (1929), What Price Innocence (1933), Broadway to Hollywood (1933) and Together We Live (1935). All in all, he wrote over 70 screenplays between 1916 and his death in 1934. While most of his films are fairly obscure today, many of them were quite successful in their day, and made Mack a good fortune, allowing him to relocate to a comfortable home in California.

The acting in the film is in a word good all around. Gertrude Olmstead playing the female lead works fine as the kind-hearted love interest, and the script even gives her something of an active part to play – even if eventually becomes a classic damsel in distress. Gertrude Olmstead has been described as a “chronically unfunny comedienne”, and the notion isn’t far off. She is a bit bland in her role, which was one of a string of leading lady parts she got in lesser films during the twenties, particularly in budget westerns. As so many other starlets in Hollywood, the Chicago-born Olmstead got noticed at a beauty pageant and got her start in films in 1920. Apart from The Monster, she is best remembered for her role opposite Rudolph Valentino in the romcom Cobra (1925), and for her role in Greta Garbo’s first US film Torrent (1926). She also starred in the 1926 comedy western with the fabulous name The Boob. Like so many other silent stars, she dropped out of acting in 1929 with the advent of sound films.

Hallam Cooley is the “straight” man to Johnny Arthur’s comedic character, but in fact the character of Amos is just as much a caricature as that of Johnny Goodlittle. And Cooley has no trouble answering Arthur’s antics in kind, creating a sort of antagonistic comedy duo forced into working together to save their asses, joined in their cause by their mutual love for Betty. With his dandy moustache Cooley was rather dashing in a Max Linder kind of style, but despite this he was never a leading man. Perhaps it was that Linderish streak that lent him an air of arrogance, which made him well suited to play “the other man”, a romantic rival, a comic relief or even villainous characters, such as “the mystery man” in The Brass Bullet (1918).

Based in Hollywood, Cooley’s film career got going in 1913, and he had good run as a supporting character actor for the next 17 years, often getting thrown in as the third wheel with stars like Mary Astor, Corinne Griffith and even Clara Bow, predominantly working for First National or Pathé. Few of his silent films are remembered today, and most of them are lost. The best known, apart from The Monster, is Beauty’s Worth (1922), in which he plays – again – “the other man” opposite a dazzling Marion Davies. With the advent of sound Cooley’s roles started to get smaller. He still had substantial parts in successful films such as Holiday (1930) and Frisco Girl (1932), but he could read the writing on the wall. By 1931 he was already practically retired from acting, although he did a handful of more films, including an uncredited bit-part in John Ford’s Mary of Scotland (1936). But by this time was had already set up as a Hollywood agent with the Hallam Cooley Agency, which represented many of the stars of the business.

One actor of some interest is Knute Erickson, playing the wacky henchman Daffy Dan. If Daffy Dan seems a bit like he’s wandered in from a Fatty Arbuckle set in the adjacent studio, it’s because this was almost the case. Daffy Dan was the vaudeville character created by Erickson in the early 1900s, and which was introduced to film in 1915 in a number of two-reel comedies, and then appeared in a couple of Fatty Arbuckle films that were never actually released in the US. The Monster was Daffy Dan’s last film outing, even if Erickson kept appearing in films in other roles, mostly bit-parts as a comic relief.

Daffy Dan was a Swedish character much like the persona that the much more famous El Brendel would adopt around the same time. However, neither Brendel nor Erickson were Swedish, despite Erickson’s claim to the contrary. Knute Erickson used to say he was born in Norrköping, Sweden, but was in fact born as Carl Erickson in Ogden, Utah in 1872. His claims of being born in Sweden have even made their way to the famously unreliable IMDb (I’ll try to fix it). But unlike Brendel, Erickson didn’t simply make up his Swedish heritage: his parents were, in fact, Swedish immigrants, possibly from Norrköping.

The rest of the cast is all A-class, even of the script doesn’t do their characters any favours. All were seasoned stock players, most of them with over a hundred credited roles under their belts during their careers: larger supporting roles in low-budget films and bit-parts in a whole assembly of high-profile movies. For science fiction fans the two most interesting names are Edward McWade, playing the owner of the general store, and Frank Austin, playing Rigo. McWade played Gorn, the keeper of the law, in the 1936 sci-fi/fantasy serial Darkest Africa (1936) and had a supporting role as Ivan in William Dieterle’s 6 Hours to Live (1932). Austin had a bit-part as a hotel clerk in the 1943 Batman serial. William H. Turner, in the small role as the insurance detective, also turned up in a supporting part in the 1925 death ray serial The Power God (review).

Dorothy Vernon in a bit-part was a legend among western extras. She was 43 when she entered the movie business in 1918, and kept on acting all the way to the age of 82, in 1957. One film historian noted that he had seen her in so many PRC westerns, that he assumed she was the out-of-work mother of character actor Charlie King. Science fiction fans can look out for her in tiny roles in Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review), Sky Bandits (1940, review) and The War of the Worlds (1953, review).

Cinematographer Hal Mohr was there at the very beginning of Hollywood and shot around 150 films or TV shows up until 1968. Along the way he won Oscars for his work on A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) and The Phantom of the Opera (1943), as well as a Golden Globe for The Four Poster (1952). Apart from The Monster, he filmed three other sci-fi films: The Walking Dead (1936, review), starring Boris Karloff and directed by Michael Curtiz, The Creation of the Humanoids (1968), and his last film The Bamboo Saucer (1968).

The female portrait in the film is about as nuanced as one may expect from a film of this sort made in 1925, but all things considered The Monster comes out quite OK from a feminist point of view. One problematic aspect for a modern viewer is the blackface: Walter James plays Caliban the Nubian with a brown-painted face. However, the film can’t really be blamed for this, since it was the common practice at the time. And the character of Caliban is played respectfully.

Most modern day critics find The Monster a disappointing film, perhaps because the expect a Lon Chaney vehicle and discover a Johnny Arthur comedy. But the film still has its defenders, such as Phil Hardy, who in The Overlook Film Encyclopedia calls it “a charming comedy thriller”, and writes that it possesses “a visual delicacy unusual in American films of this type”. Hardy writes that West did go on to make much better films in the sound era, “but in his short career he did nothing so wittily conceived and executed”. The film received mixed reviews at the time, with Variety feeling that it was too rushed and doesn’t carry the same suspense as the play, however, the reviewer praised the movie’s cast and rightly predicted it would be a money-maker. Unsurprisingly Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times didn’t like the film, but Hall pretty much hated all genre movies. However, Exhibitor’s Trade Journal praised the burlesque feel of the film, and C.S. Sewall of Moving Picture World called it “the best of these types of stories to have reached the screen”. The Alton Evening Telegraph noted that “the audience gasped, grasped their seats in excitement and held their breath” while watching the film, and went on to say that it “holds one’s interest by its tense moments, harrowing incidents and comic relief”.

My thanks this time goes to Thomas S. Hischak, author of the encyclopedia Broadway Plays and Musicals, for the information on the plot of the play, and to Soister, Niconella and Joyce, the editors of American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913–1929, for their superb entry on The Monster.

Janne Wass

The Monster. 1925, USA. Directed by Roland West. Written by Roland West, Willard Mack, Albert Kenyon and C. Gardner Sullivan, based on the play by Crane Wilbur. Starring: Johnny Arthur, Hallam Cooley, Gertrude Olmstead, Lon Chaney, Charles Sellon, Walter James, Knute Erickson, Frank Austin, Edward McWade, Ethel Wales, William H. Turner, Dorothy Vernon. Cinematography: Hal Mohr. Editing: A. Carle Palm. Art direction: W.L. Heywood. Produced for MGM.

EDIT: 2022-01-22: Correction: Sherlock, Jr is a Buster Keaton film, not Harold Lloyd. Thanks for bringing it to my attention!

Leave a comment