This early colour film (1932), impeccably directed by Casablanca-maker Michael Curtiz, is a stylish and atmospheric old dark house thriller with a gruesome sci-fi twist. Unfortunately it’s also an attempt at Groucho Marx-style comedy with a Lee Tracy in the lead as a wise-cracking reporter, whose comedy repertoire isn’t up to the task. Fay Wray and Lionel Atwill shine, and the whole thing has the delicious look and feel of a faded pulp magazine. (7/10)

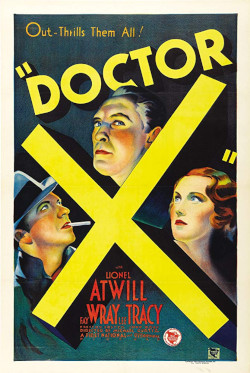

Doctor X. 1932, USA. Directed by Michael Curtiz. Written by Robert Tasker, Earl Baldwin, George Rosener. Based on play by Howard Warren Cornstock, Allen C. Miller. Starring: Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray, Lee Tracy, Preston Foster, John Wray, Harry Beresford, Arthur Edmund Carewe. CProduced by Hal B. Wallis, Darryl F. Zanuck. IMDb score: 6.5 Tomatometer: 75. Metascore: N/A.

This curious cult classic has earned a special place in the hearts of horror and sci-fi fans, as it is the first science fiction or horror feature film to be filmed in colour. It’s also the first sci-fi film made by Warner Bro:s, and one of its earliest horror movies. The movie came on the heels of struggling mid-tier studio Universal’s tremendous successes with Dracula and Frankenstein (1931, review) — the latter, released in November 1931 was one of the highest grossing film of the year, both in the US and world-wide. Other studios, previously uninterested in horror films followed suit. Paramount was one of the first to respond, releasing the classy Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in December 1931 (review) and the minor masterpiece Island of Lost Souls (review) in December 1932. Drawing off the immense popularity of the radio show, Fox released Chandu the Magician with Dracula star Bela Lugosi as the villain in August 1932, and MGM answered three months later with The Mask of Fu Manchu with Boris Karloff in the title role.

But the quickest to respond was perhaps the most surprising of the studios: Warner Bro:s, considering Jack Warner’s famous dislike of horror and sci-fi. But money talks, and even before the release of Frankenstein, Warner made the Dracula-esque hypnotism drama Svengali, with former Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde star John Barrymore in the title role.

Svengali was directed by Archie Mayo, but Warner then turned to one of its top scene-crunchers, Hungarian immigrant Michael Curtiz, still far from the fame he would later garner with efforts like Captain Blood (1935), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), Casablanca (1942) and Mildred Pierce (1945). In 1931 Curtiz, having made his name in Europe as one of the founders of Hungarian cinema, and in the twenties in Germany with horror films like Labyrinth of Horror (1921) and biblical epics like The Moon of Israel (1924), was respected at Warner for his impeccable craftsmanship, his reliability and his ability to turn out quality pictures on a short schedule. Warner wanted a follow-up to the success with Svengali, and assigned Curtiz to direct The Mad Genius, featuring the stars of Svengali, John Barrymore and Marian Marsh. The film opened on November 7, 1931, and included a then still unknown bit-part player called Boris Karloff. Frankenstein came out two weeks later.

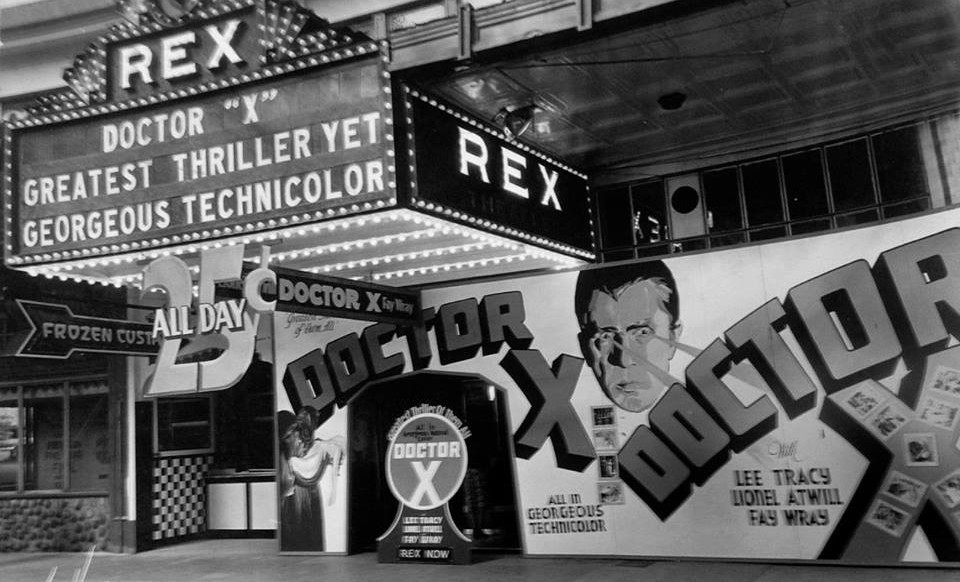

By December 1931 it was clear that horror films, even science fiction films, could be money-makers, and that audiences had a thirst for macabre monster movies. It was assumed that there would be an imminent sequel to Frankenstein from Universal, even though it later turned out that director James Whale wasn’t interested, and one can assume that Karloff didn’t want to reprise the role without Whale at the helm. Nevertheless, Warner wanted a piece of the cake. At the same time Warner had a deal with Technicolor which included two more two-strip Technicolor films. Technicolor’s two-strip technique had been around since the early twenties, and there were rumours that a revolutionary three-strip technique was just around the corner — in fact Disney unveiled the first three-strip animation short Flowers and Trees in July 1932. Two-strip films were fast becoming obsolete. The problem was, filming in colour was double as expensive as filming in black and white, so whatever was going to be filmed had to be fairly cheap but still sure-fire hits. So Jack Warner thought he’d hit two birds with one stone, and assigned Michael Curtiz to quickly direct two horror films in two-strip Technicolor. The first was Doctor X, which opened in August 1932, and the second, better known film, was Mystery of the Wax Museum, which had its premier half a year later. The films were made with pretty much the same crew and even cast.

Doctor X is not only noteworthy because it was the first science fiction and horror movie filmed in colour. It also introduced two actors who were to become legendary in both genres: Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray. This was British thespian Atwill’s first foray into mad scientist territory, one that he would return to repeatedly, especially after his career had taken a highly publicised nose-dive in 1942. Atwill was part of a small team of actors that in the thirties and forties (and even beyond) took up the mantle from Karloff and Lugosi when these weren’t available to meddle in things that man was meant to leave alone. The main competition came from John Carradine and George Zucco. Of these, Atwill was by far the most prolific mad scientist, and may even have out-karloffed Karloff. I haven’t counted, but if he didn’t play more zany medical doctors or radiation experts than Karloff, then this was simply because of his early demise in 1946. Fay Wray, of course, would be forever immortalised by her legendary scream in King Kong (1933, review), of which she gives us a little taste in Doctor X.

The purported lead actor of Doctor X was Lee Tracy. Tracy, a Broadway star turned Hollywood darling, does his signature role as a fast-talking, wise-cracking reporter with a heart, stumbling over (or rather: inserting himself into) a gruesome murder mystery. His character Lee Taylor hangs out on the New York docks one night, trying to get a foot into the morgue, where police are investigating a bizarre string of murders. Four victims have fallen prey to “the moonlight murderer”, who first strangles them with his bare hands and then proceeds to carve out pieces of their flesh – for assumed cannibalistic reasons.

However, the actual main character is the titular Doctor X, or less mysteriously: Doctor Xavier, played by Lionel Atwill. Originally called in by the police to render them his services as a pathologist, he’s soon embroiled in the affair for another reason, namely as a potential suspect: all killings have taken place around his Academy of Surgical Research, and what’s more: they have been done using a certain kind of scalpel found only at his institute. After giving the police a walk-through, introducing all the possible — or impossible — suspects among the staff, Doctor X begs the police not to publicise their suspicions and tarnish the institute’s good name. Instead, he guarantees them that he has a method of finding out — scientifically — who the killer is, and asks the police for 48 hour to carry out his own investigation. And in one of those bizarre Hollywood cases of the suspect investigating himself, he gets his 48 hours, and calls together his for (or rather: three) main suspects at his private lab/mansion on top of a creepy hill.

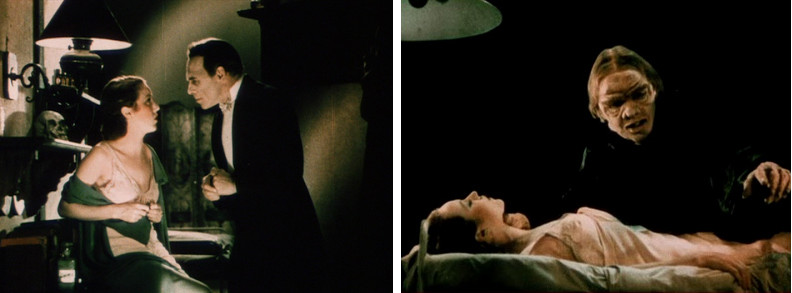

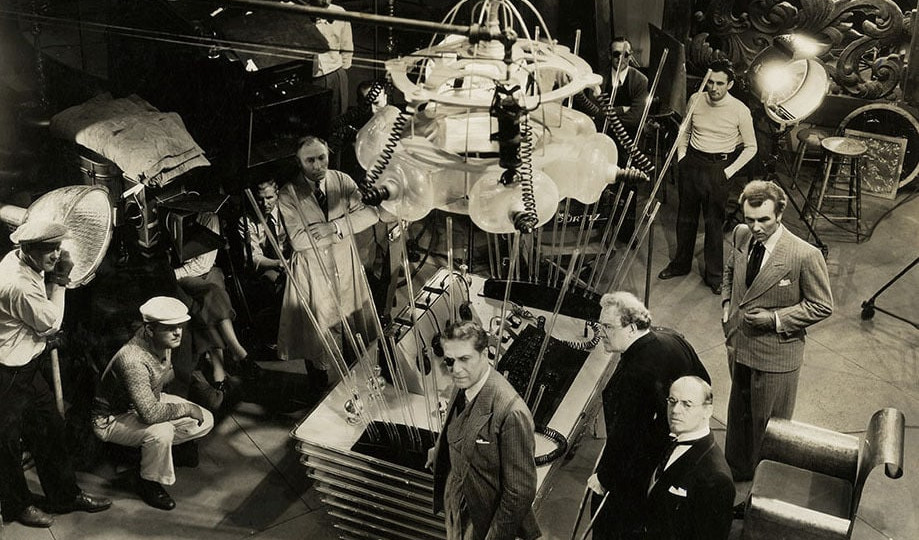

As Fernando F. Croce puts it on his site Cinepassion, the suspects are “quite the gallery: Dr. Preston Foster unscrewing his artificial arm to better contemplate a beating heart in a jar, Dr. John Wray with brain cells under the microscope and girlie magazines strewn around the lab, Dr. Arthur Edmond Carewe marveling at lunar rays through a metallic eyepatch.” The strangeness of the characters is hightened by the lighting, mise-en-scene and visual introduction of the suspects, all in beautifully pulpy mad scientist style, influenced by both Frankenstein and pulp magazine illustrations, and made deliciously macabre through Curtiz’ wonderfully suggestive, expressionistic camera.

Our intrepid reporter Lee Taylor manages to sneak into the mansion as Dr. X does psychological and “radioelectrical” experiments with a strange machine on his fellow scientists to provoke a neurological response to different stimuli. In practice, this means that Doctor X stages re-enactments of the murders with the help of his sinister butler Otto (George Rosener), his maid Mamie (Leila Bennett) and his daughter Joanne (Fay Wray), all while strapping the suspects — including himself — into a strange machine that works like a lie detector. The logic here is that the pathological killer will be aroused by seeing his murders re-enacted, and this arousal will be read by the machine. As Doctor X is himself a suspect, he can’t operate the machine. However, this job is left to Dr. Wells: the murders have all been committed by a man with two very strong hands, and Dr. Wells, being one-armed, is thus above all suspicion.

The film also provides one of these bizarre female portraits that would become staples on mad scientist films – a grown-up daughter with a rather unhealthy attachment to her father. Fay Wray in her first horror film plays Joanne Xavier, who fusses over the health her highly vital and energetic father who doesn’t really seem to need any fussing over. The film is one of the first to start the curious practice of fathers refusing to, for example, send their daughters away to, say, their aunt in Iowa, when a crazy serial killer is prowling the grounds, and instead uses her in his his murder re-enactment with the suspected killer sitting in the very same room. Wray, of course, is mainly in the film to provide the hero with a romantic interest and a damsel in distress to save. That said, Joanne Xavier is not entirely without character and spunk, at one point holding Lee Taylor at gun-point. While not the the most interesting, this is at least not the worst or even remotely the most uninteresting of similar female roles in classic Hollywood horror films. Wray, whose actual acting talent has unfortunately been obscured by her scream queen fame, handles the role well.

Taylor spends most of his time wise-cracking with police-officers, nightwatchmen, dead bodies and skeletons in closets, burning all of them with his electrical handshake buzzer – a prank that becomes highly tedious as the film moves along, as well as romancing Joanne. But still, as per usual with his roles, he brings a touch of genuineness and humanity to his wise-cracker, and there are moments when his character seems to be actually ashamed of his double-dealing antics, as if his hard-boiled attitude was more of a professional facade than real personality. This said, Tracy is mostly in the film to act as audience stand-in and provide comic relief, in the old tradition or the old dark house movie. But screenwriters Robert Tasker and Earl Baldwin wisely removes him from the proceedings (locked in a closet or passed out from gas) when things get really creepy, thus maintaining the horror feel of the film without ruining the suspension with one-liners.

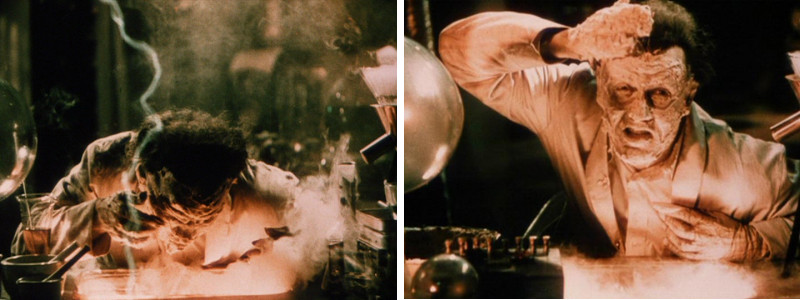

Needless to say, Doctor X’s experiment goes horribly wrong as the moon killer strikes again, within the very walls of his mansion. Red herrings abound, and they are all wonderfully delicious. I’m trying not to spell out too much, but friends of classic horrors will probably work out who the killer is during the film’s first fifteen minutes, if not from this article alone. It seems that the killer has been conducting experiments with ssssynthetic flessshhh, which is apparently why he carved flesh from his victims. The scene where the killer transforms himself into a monster by smearing ssssynthetic flessshhh over his face and head by the light of crackling electrical equipment is wonderfully creepy and freaky, much enhanced by the fleshy red-tinged two-strip colour. The result is something with a vague resemblance to Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera, combined with the melted feel of Paul McCrane’s unlucky villain in Robocop (1987).

This was one of two creepy films dealing with body horror released in 1932, the other being the afore-mentioned Island of Lost Souls. Both were made at a time when movies were getting ever more realistic due to the introduction of sound, which allowed for far more intricacy in the plot — but another important factor was that film technology was advancing rapidly, the art of makeup, among other things, and movie budgets were getting bigger. Although the Motion Picture Production Code or the Hays Code had been introduced in 1930, it wasn’t enforced until 1934, making these films essentially pre-Code movies, which meant that they could still get away with things that might have seemed rather gruesome or inappropriate, and which would have been nixed only two years later. In fact the kind of body horror seen in these films wouldn’t show up again in US movies until the enforcement of the Code started to slip in the fifties, and gave us films like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1955, review), The Blob (1958) and The Fly (1958).

Art director Anton Grot’s sets are beautifully designed in order to evoke a sense of foreboding and mystery, labs cluttered with strange equipment and a New York waterfront that evokes European Gothic. Polish-American Grot was a favourite of Curtiz‘, and they collaborated on 15 films. One of the pioneering art directors in the early days of American cinema, Grot pioneered the practice of delivering a complete collection of set sketches to the director and crew before filming began, for continuity, which helped to plan shooting and lighting. He especially flourished at Warner in the thirties and forties, and was nominated for an Oscar five times. In 1941 he received a technical Oscar for inventing Warner’s wave and water ripple machine for the 1940 pirate film The Sea Hawk, starring Errol Flynn. Grot designed all four of Warner’s early thirties’ horror films.

Apart from its macabre ending, what elevates this film from a standard old dark house romp is the stunning cinematography and lighting. Michael Curtiz’ clearly shows that he is no mere studio hack churning out frames to put bread on the table. During his career Curtiz worked in every imaginable genre, adapting to each so seamlessly that he is often forgotten when discussing the great directors of the Golden Age of Hollywood. DeMille, Hitchcock, Lang, Ford or Wilder all had their unique directorial styles that they are remembered for, often elevating a script far beyond the written material as it was processed though their own sensibilities. Curtiz’, on the other hand, let the script determine the style of the film. However, with his horror movies, Curtiz could fall back on his experience in early European cinema. While seldom counted as one of the pioneers of expressionism, Curtiz was contemporary to the greats Fritz Lang, Robert Wiene and F.W. Murnau, and in was in fact a force to be reckoned with before any of these had directed a single frame of film. In 1919 he directed one of the very first monster movies: Alraune (review), later made into a smash hit in 1928 by Paul Wegener, with Brigitte Helm as the titular monster. His Dracula movie Drakula halala (1921) predated Murnau’s Nosferatu by one year.

Despite the fact that Doctor X is a colour film, the lighting is a throw-back to the black and white expressionist films, drenched in ominous darkness with hard dramatic lighting creating eerie highlights and long, brooding shadows. There’s a claustrophobic feel to the film, as the action seems to be eternally boxed in by high walls, narrow passageways, screens and drapes and buildings that almost seem to encroach on our personal space.

The film is one of a string of movies of the early thirties produced in Technicolor’s new, improved two-strip colour process, that removed grain and speckles as compared to previous efforts. At the same time, it was one of the last to be produced with the two-strip technique, that allowed only for red and green colours. Without getting too technical, the Technicolor process was created at a time when colour film for film cameras was not yet available. Instead, Technicolor created a camera with a prism that split the red and the green colours from light, which were then exposed in the camera, on alternating frames on a single strip of black and white film — meaning the camera had to be cranked at double speed, or 48 frames a second. These frames were then separately transferred to two different negatives (hence the name “two-strip process”), which were dyed using a subtractive colour process, leaving one green-tinted and one red-tinted strip of film. Initially these two strips were cemented together, but this left a grainy finished product which was susceptible to unpredictable bulging due to the heat from the projector. This lead to Technicolor refining the technique, by transferring the dye to a third, single strip of gelatin-coated film, which was the technique used for Doctor X. The colours red and green were chosen as they were deemed as those most abundant on film of the RGB spectrum: red for human skin, green for trees and grass. In between, the two also allowed for a brownish illusion of orange and yellow. Blue, however, could not be reproduced by the process, eliminating shots of blue skies, for example. While not necessarily naturalistic, the films using the two-strip process have a distinct feel to them.

With the Technicolor process also came the Technicolor company’s own art director. Very much like we today have the possibility to greatly influence a film’s look and feel by digital grading, Technicolor films would look drastically different from one another depending on what filters were used. The Technicolor art director would often create a distinct palette for each film, giving her (it was mostly a she) a surprisingly large influence over the finished product. This power was almost always wielded by Natalie Kalmus, wife of Technicolor’s inventor and owner. This was the case with Doctor X as well.

The red and green gives the film a strange, atmospheric feel, especially when combined with the low lighting, although it’s still a bit grainy compared to black and white and the colours tend to merge in a rather muddy brown. Still, the process makes Fay Wray glow on screen, and one can only imagine the joy of the male audience seeing Ms. Wray’s exposed thighs resting below a revealing swimsuit on the beach in a precarious close-up, awash with fleshy pink. This is one scene, among others, that probably wouldn’t have made the cut under the enforced Hays code two years later.

Double Oscar-winning cinematographer Rey Rennahan (Blood and Sand, Gone with the Wind) also contributes to the ominous mood with expressionistic shadow plays and limited lighting.

Curtiz would go on to make another stylish effort as Warner again ventured into karloffian territory in 1936 with The Walking Dead (1936, review).

Michael Curtiz was born as Manó Kaminer in Budapest in 1886, and Hungaricised his name to Mihaly Kertész in 1905. After having worked for some years a an actor, he became a director at Hungary’s National Theatre, and soon developed an interest for the emerging medium of film. In 1912 he directed Hungary’s first feature film, Today and Tomorrow, and quickly established himself as one of the fathers of Hungarian cinema, alongside director/producer Alexander Korda and influential cinema owner and movie promoter Mor Ungerleider. In 1917 he became the head of production for a small company called Phoenix Films. Kertész left for Germany in 1919, when the Hungarian film industry was nationalised under the short-lived Hungarian communist rule, which was overthrown by the far-right in 1920. After working briefly for the national film company Ufa, now under the name of Michael Kertész, he left for Vienna, where he came to work for the company Sasha Film, for which he made the 1924 film Moon of Israel, which attracted the interest of Jack and Harry Warner. Harry flew out to Vienna to watch Kertész work, and was impressed enough, especially by Kertész’s innovative camera work and expressionist sensibilities, to bring him to Hollywood.

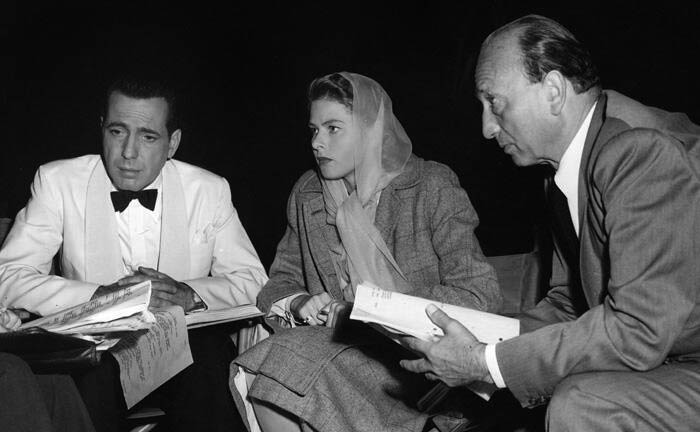

Curtiz is famous for having discovered Errol Flynn, John Garfield and Doris Day, as well as for turning actors like Olivia de Havilland, Joan Crawford, Ingrid Bergman and not least Humphrey Bogart, into superstars. He is infamous for never learning English properly, as well as for being something of a slave-driver on set. He himself, for example never had lunch, as he felt in made him drowsy, and therefore he resented actors that took lunch-breaks, calling the “lunch bums”. While reportedly a kind-hearted man off the set, his work ethic and drive made him blunt and ruthless towards his co-workers, including actors, especially if they were late, lazy or ill-prepared. Despite this, his favourite actors kept returning to him in film after film, as if they realised that in pushing them, he also brought out the best in them. Even when working on big pictures, he was able to make 4 to 6 pictures a year, thanks to Warner setting aside two different film crews for him: while one was filming, the other was preparing the next film, so that Curtiz could jump straight into the action. Curtiz won an Oscar as best director for Casablanca. He passed away in the mid-sixties from cancer.

Like so many other horror films at the time, Doctor X was adapted from a stage play. Written by Howard Warren Cornstock and Allen C. Miller, the 1931 play was originally called The Terror, but the title was changed to Doctor X for its Broadway premiere. The play was more of a traditional old dark house mystery, a genre that was hugely popular on stage and had a number of great hits on the screen as well. The genre originated with Mary Robers Rinehart’s mystery novel The Circular Staircase from 1908, which she adapted into a mystery comedy called The Bat in 1920 — an experimental play in which the mystery was kept a secret until the very end of the show. It proved an enormous success and garnered numerous imitations, the most notable perhaps being John Willard’s The Cat Creeps in 1920. By 1932 both had been turned into both silent and sound films, all of them very successful. Agatha Christie had also made her debut as a mystery writer in 1920, and was nearing the peak of her success in the early thirties, with humorous mystery novels also leaving the solution to the enigma to the very last pages of he book. A trope in many of these plays and books was that there was something seemingly supernatural going on, and it was the investigator’s job to make sense of it all: in the end the mystery always turned out to have a perfectly natural solution. But some of the early US horror films, such as The Monster (1925, review) and Dracula, subverted these trends, bringing in either science fiction or the supernatural to the mix.

The play Doctor X originally brought together the reporter, his managing editor and the latter’s wife to the good doctor’s lab, together with three scientists. Contemporary critics gave it favourable reviews describing it as a “melodrama of bizarre”. Warner also bought it with a serious horror film in mind, and they had originally envisioned Bela Lugosi in the title role. However, according to Jon Towlson, the author of the book The Turn to Gruesomeness in American Horror Films 1931-1936, the studio’s head of production, Darryl F. Zanuck steered the movie in a different direction. Taking his cue from the silent horror comedies of the twenties, he wanted to invert Universal’s motto of “80 percent horror, 20 percent comedy”, turning the movie into a “newspaper thrill comedy”. However, according to Towlson, Zanuck wanted to make sure that the “limited horror scenes would be the grisliest yet”.

This was in line with Jack Warner’s dislike of horror films, and with the two previous horror entries. While we might nominally call Svengali and The Mad Genius horror films today because of the “monstery” hypnotist character played with great ham by John Barrymore, they are both, as a matter of fact, more melodramas than actual horror movies. The same thing can be said about Mystery of the Wax Museum, even if that film is the one that comes closest to being a straight horror movie.

Towlson further writes that Zanuck had a big hand in completely rewriting George Rosener’s original screen draft with the help of Robert Tasker and Earl Baldwin. But he didn’t necessarily remove horror elements, but add comedy. And, in fact, he played up the gruesome body horror of the “synthetic flesh” sequences, adding on extra transformations, and turning the killer into a horrific-looking blob of a monster. The pink-ish colour scheme and the dramatic expressionist lighting, as well as Curtiz’ masterful camera setups add to the gore and horror of the scene. This was probably the most graphic and gruesome sequence shot in a horror movie up to date, and would remain so well into the fifties. To a thirties audience, thinking Frankenstein was the height of gruesomeness, the scene in Doctor X must have been outrageous. Paradoxically, the Hays office at the time had no qualms over the script, probably because it was so laced with comedy, and simply stated to Zanuck that he should take care how to film the murder re-enactment scenes. Oddly enough, the US censors had no problems with the finalised scene either. This changed in 1934, when the film was submitted to the now much harsher Hays office, and the movie was effectively banned.

The makeup was designed by the Max Factor company, which at the time specialised in movie makeup, but had at that point just been dealing with ”normal” makeup – this was the first time they created a character for a creature film. Max Factor were assisted by Warner’s head of makeup, Perc Westmore, one of the six legendary Westmore brothers who came to completely dominate Hollywood’s burgeoning makeup industry.

The finished result is a mixed bag. It generally received favourable reviews from critics, and it did very well at the box office, becoming one of Warner’s highest grossing films of the year. Still, to a modern viewer the the comedy feels out of place and extremely forced, even when it is not terrible. Lee Tracy’s physical comedy is a lot better than the script’s verbal ditto. Tracy does a likeable character, and he was a kinetic and charismatic performer, always in motion, always reacting to his surroundings. He is at his best when he’s talking to himself or the skeletons in the closet, or jumping at a cuckoo clock in the kitchen. But the wise-cracks and puns have aged really badly, and when the script breaks out hand buzzers and exploding trick cigars, you as an audience feel insulted.

There are more holes in the logic of the this film than a sieve, starting with the basic premise that the police would let one of the main suspects carry out his own murder investigation. But as a viewer you glance over these, as the film isn’t supposed to make much sense in the first place. A bigger problem is the forced marriage between comedy and horror, that just doesn’t work in the same way that James Whale’s morbid humour does — which was always integrated in the film, without winking at the audience. Here Lee Tracy seems to inhabit a completely different film than the rest of the cast, which is why the only way to maintain the horror aspect of the movie is to completely remove him from the sequences that are supposed to be taken seriously — and after the fact he pops up again, defusing the tension by some ill-advised wise-crack.

The cast is a good ensemble. British stage veteran Lionel Atwill as the centrepiece of the film could have taken the opportunity to ham up his part, but instead plays the semi-mad Doctor X with a straight face, integrity and gusto. He becomes the glue holding the film together, and grounding it in some kind of reality. Lee Tracy works surprisingly well, despite the fact that he seems to inhabit an entirely different film than everybody else. Fay Wray, making her genre debut, shows the qualities that made her such a popular ingénue: her almost virgin-like innocence and the natural lightness of her acting. The written role is wafer-thin, but Wray manages to fill it with emotion and character, making her stand out in stark contrast to the myriad of horror film leading ladies over the years to come who did little more than stood around acting scared or pretty. There’s something inherently likeable about Wray that makes the audience care about her characters. Preston Foster, John Wray, Harry Beresford and Arthur Edmund Carewe as the four ominous scientists are all fantastic, providing the film with infinite ham. The cast is rounded up by Leila Bennett as the hysterical housekeeper and original screenplay writer George Rosener as the sinister butler.

Atwill came off a successful Broadway career where he had been mostly playing dashing leads. Now at 47 he was a bit old for romantic hero roles, and Doctor X opened a whole new career for him. In 1933 he was cast in prominent roles in no less than five horror or mystery films, including The Vampire Bat (1933, review) and Mystery of the Wax Museum. But his theatrical training, his impeccable British dictation and his commanding on-screen persona also garnered praise in a number of prestigious productions such as Captain Blood and The Hound of Baskervilles (1939). He actually managed to stay away from horrors between 1933 and 1939, when he was cast in one of his most memorable roles, as the one-armed police detective in Son of Frankenstein (1939, review). This started him on the career path that he is so beloved for by horror and sci-fi fans alike, making appearances in films like The Ghost of Frankenstein (1941, review), Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943, review) and The House of Frankenstein (1944, review), Man Made Monster (1941, review), The Mad Doctor of Market Street (1942, review), House of Dracula (1945, review) and many more. His career took a sharp turn for the worse in 1943 when he was sentenced for an ”orgy” in his house, and was thereafter mostly shunned by all major studios.

Although this was Fay Wray’s genre debut, she was already a veteran in the business, having acted in B films for over ten years, the latter five mostly as a leading lady in western and crime films. Despite her slightly limited range, Fay Wray has a naturalism and a charisma that draws the viewer in, and while staying within her limits, she is actually quite a talented actress. In Doctor X her role consists mostly of being either hysterical or alluring, and she does both well. Kudos most go to both director and writers for not having her faint once, and actually giving her a few hero moments, swinging a gun and rebuffing Taylor’s advances. On the other hand, she was the only person not chained to a chair in the final scene, and had ample opportunity to kick the killer in the nuts during his long harangue about synthetic flesh, but opted for being a piece of shivering flesh instead. Wray also introduces THAT scream – a scream which she would of course immortalize forever just a year later in King Kong – which has made her a timeless legend.

While forever remembered for her turn in King Kong and for her status as the original scream queen, Wray actually didn’t make as many horror films as you may think. In fact, she only very briefly appeared in genre pictures between 1932 and 1934. After Doctor X, she appeared in The Vampire Bat, Mystery of the Wax Museum, King Kong and Black Moon (1934), and then never set her foot on a horror set again, despite appearing in over 100 films. She even turned down a cameo in Peter Jackson’s 2005 King Kong remake. She turned to TV in the fifties and continued acting into the sixties, after which she retired. She passed away in 2004 before the filming of King Kong commenced, and two days after her death the Empire State Building dimmed its lights for 15 minutes in memory of her famous scene in the original movie. While she never won any acting awards during her active career, Wray was honoured with a number of (albeit perhaps lesser) lifetime achievement awards later in life, including a Crystal Award for women in film and a Saturn lifetime achievement award.

Lee Tracy was a Broadway star who specialised in fast-talking newspaper men from the very beginning of talking pictures. He thrived in films like Liliom (1930) and Dinner at Eight (1933), as well as in the Jean Harlow comedy Bombshell (1933), despite a drinking problem and a propensity for drunken antics. His career was momentarily disrupted in 1933, while filming Viva Villa on location in Mexico. According to legend, a drunken Tracy would have urinated on a passing military parade from his balcony. The alleged incident caused an uproar in Mexican newspapers, and Tracy was taken off the film, along with director Howard Hawks who refused to testify against the film’s star. However, the movie’s cinematographer Charles G. Clarke, who stood outside the hotel when the incident was supposed to have taken place, wrote in his autobiography that this never happened. According to Clarke, what really happened was that Tracy was standing on his balcony watching the parade, when a Mexican in the street “made an obscene gesture” at him. Tracy then, perhaps unwisely, replied in kind. The next day Mexican newspapers were filled with stories about how Tracy had “insulted Mexico, Mexicans in general, and their national flag in particular”. In order to be able to continue filming in Mexico, MGM decided to throw Tracy to the wolves. The incident didn’t particularly hurt his career, though. Despite a number of successful films, Tracy was never the number one choice for prestigious movies, and continued to work steadily throughout the thirties and forties, and found ample work in TV in the fifties and sixties. In 1964 he made a last comeback to the big screen, playing the president of the United States in the film The Best Man, for which he received both an Oscar and a Golden Globe nomination for best supporting actor.

Of the four scientists called to Doctor X’s mansion, the one playing the one-armed Dr. Wells, Preston Foster, probably became the best known to general audiences, even if all four were highly regarded character actors both on stage and in film. Foster, like so many actors in the early days of the talkies, was a stage actor who suddenly found himself in demand in the movies, as studios suddenly had to recruit large numbers of thespians who were used to deliver lines, rather than act silently, which was really a whole other art form. Doctor X was one of his earliest movies, and studios quickly came to regard him highly for his versatility and range. Most of Foster’s memorable roles were villains, but he was also allowed to play the occasional leading man in fairly prestigious films, such as The Last Days of Pompeii (1935) by King Kong (1933) makers Cooper and Shoedsack, as well as Samuel Fuller’s I Shot Jesse James (1949). However, he is probably best remembered for his heavy roles in crime dramas like I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) and The Informer (1935). He also had a successful career on the side as a vocalist in a band and a radio performer.

In a small role as ”Cathouse Madame” we see Mae Busch, an actress with a rollercoaster career, best known for playing the female lead in Tod Browning’s The Unholy Three (1925) and Oliver Hardy’s wife in Sons of the Desert (1933). For much of her career she was confined to bit-parts, though. Selmer Jackson appears as the newspaper editor. He was a staple bit part player in over 400 films, and does appear in The Green Hornet (serial, 1940), The Ape (1940, review) and Mighty Joe Young (1949).

Genre fans will naturally know that Doctor X was one of the films referenced in the cult musical The Rocky Horror Picture Show’s (1975) title song: “Science fiction double feature / Doctor X will build a creature“. They will no doubt also recognise a resemblance between Harry Beresford’s portrayal of the paraplegic scientist Dr. Duke in the former and film and stage and TV actor Jonathan Adams’ ditto of Dr. Everett Scott (Great Scott!) in the latter.

Incidentally, Doctor X was filmed as a black and white version alongside the colour version, with Richard Towers in charge of cinematography. This was done because all theatres were not equipped to show colour films, especially abroad, and making black and white copies was cheaper than making colour copies. One can detect dissimilarities between the two versions mainly in the comical ad-lib scenes, and in some other scenes when the Technicolor camera ran out of film and additional takes were required. In a lot of theatres, the black and white version was the only one shown. Despite the name, Warner’s 1939 film The Return of Doctor X (review) is not a sequel, but deals with a different Doctor X. It is, however, one of Humphrey Bogart’s few horror films. Bogart and Curtis would, of course, famously meet up in 1942 for Casablanca.

Despite the awkward pairing of comedy and horror, Doctor X is still considered a minor gem by genre fans, not only because of its gruesome horror elements, but mainly because it is a very well directed and edited film. During its fairly short running time of 77 minutes Michael Curtiz keeps the direction tight and atmospheric, with a surprising array of inventive and dramatic camera angles and a mobile, fluid camera. The movie is extremely well edited. One sequence that is especially memorable is the final re-enactment of the murders, where it shows that editor George Amy is well acquainted with the Soviet montage theory, and with Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1928). According to Brian Senn’s book Golden Horrors; “Editor George Amy employs 25 cuts in only 50 seconds in order to produce a sense of chaotic urgency and excitement”.

Curtiz also makes good use of what he coined “the curious camera”, wherein a moving camera follows characters around in unbroken shots, as if it represented the eyes of a curious person, often “hiding” behind corners or objects, at the same time placing objects in the foreground, creating a sense of depth. Even the sets of the film were thought of as characters: art director Anton Grot explained in the film’s press kit that he added menace to the design by giving top-heavy effects to doors and windows, and designed low arches to invoke a sense of overhanging danger: “We design a set that imitates as closely as possible a bird of prey about to swoop down on its victim”.

Working conditions were apparently gruelling: even on black and white pictures a lot of hot lights were required in those days, and when shooting colour films at double speed, double the amount of light was required, even on such a dark film as Doctor X. Apparently it was so hot on set that the wax figures representing the victims in the murder re-enactment scenes melted. In addition to this, Curtiz was infamously hard on his cast and crew: he worked around the clock, and expected everyone else to do the same. He is well known for being especially averse to lunch breaks, not only because the production ground to a halt when actors took lunch breaks, but because he found that they often became sluggish and less energetic after eating. Fay Wray wrote in her autobiography: “Michael Curtiz was a machine of a person — efficient, detached, impersonal to the point of appearing cynical. He stood tall, militarily erect; his calculating, functional style made his set run smoothly, without humour. He had a steely intelligence and movie making know-how that made you feel there was a camera lens inside his cool blue eyes.”

Doctor X is a flawed gem among sci-fi horrors. At its greatest moments it has some of the best directed horror scenes of the thirties, and the finale is almost unsurpassed among pre-seventies horror films in its fleshy gruesomeness. The design and lighting is gorgeous and the acting top-notch. Lee Tracy is great as long as he keeps his mouth shut, but the decision to combine the heroic lead and the comic relief in the same character is the film’s downfall. The movie tries to go for a Groucho Marx-style machine gun barrage of absurdist commentary, but, alas, Tracy was no Groucho Marx, and most of the time what comes out of his mouth is cringe-worthy. But it’s a highly enjoyable film, which has the look and feel of a faded pulp magazine.

Janne Wass

Doctor X. 1932, USA. Directed by Michael Curtiz. Written by Robert Tasker, Earl Baldwin, George Rosener. Based on the play The Terror by Howard Warren Cornstock and Allen C. Miller. Starring: Lionel Atwill, Fay Wray, Lee Tracy, Preston Foster, John Wray, Harry Beresford, Arthur Edmund Carewe, Leila Bennett, Robert Warwick, George Rosener, Willard Robertson, Thomas E. Jackson, Harry Holman, Mae Busch, Tom Dugan, Selmer Jackson. Cinematography: Rey Rennahan, Richard Towers (b/w). Editing: George Amy. Art direction: Anton Grot. Sound: Robert B. Lee. Makeup: Ray Romero and Perc Westmore from Max Factor co. Hair: Ruth Pursley. Special effects: Fred Jackman Jr. Assistant directors: Al Alleborn, Marshall Hageman. Produced by Hal B. Wallis, Darryl F. Zanuck for First National/Warner.

Leave a comment