NO RATING: FILMS LOST OR UNAVAILABLE

Alraune is a forgotten movie monster that for a a few decades during the silent era fought for popularity in Europe with the likes of the Golem, Mr. Hyde, Frankenstein and Dracula. This first major female cinematic monster is best known in the guise of Brigitte Helm in films from 1928 and 1930. But we’ll be looking at the two movies that spawned the trend, both made in 1918, and both unseen and forgotten by most of the world.

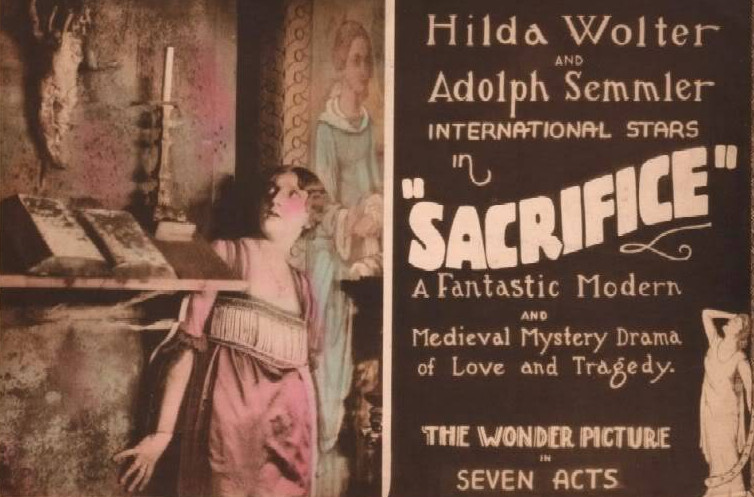

Sacrifice (Alraune, die Henkerstochter, genannt die rote Hanne). 1918, Germany. Directed ny Eugene Illés & Joseph Klein. Written by Carl Fröhlich, Georg Tatzelt. Inspired by Hanns Heinrich Ewers’ novel Alraune. Starring: Hilda Wolter, Szokol Aoles. Produced for Luna-Film.

Alraune. 1919, Hungary. Directed by Michael Curtiz & Edmund Fritz. Written by Richard Fálk. Based on Hanns Heinrich Ewers’ novel Alraune. Starring: Gyula Gál, Rozsi Szöllösi, Margit Lux. Produced for Phoenix Film and Hunnia Filmvallalat.

This post will not be so much a review as it will be an article about two films, for the simple reason that none of these movies are available for home viewing. Both films are loosely based on Hanns Heinrich Ewers‘ 1911 novel Alraune — one more so than the other — and they are the first and the second movie adaptations of the story of Alraune, or Mandrake in English. Both were filmed in 1918, however one of them was released in January 1919.

While I do not normally write about lost films, I sometimes make exceptions when I deem a film to be of special historical interest, such as the first cinema adaptation of a well-known franchise, story, character or theme, and I have done a handful of these articles in the past — even for films that were planned, but never made. The films in question this time are Alraune, die Henkerstochter, genannt die rote Hanne (“Alraune, the hangman’s daughter, called Red Hanne”), released in the US as Sacrifice, and Alraune, which premiered in Hungary in January 1919, and apparently never got a release outside Central Europe. The former was directed by the Hungarian director Eugene Illés in Berlin, and the second by another Hungarian director, Michael Curtiz, in Budapest.

None of these films can be considered lost treasures or be claimed to have had any lasting cinematic significance. But they are interesting inasmuch as they are the first cinematic outings of one of the most popular movie monsters of the early decades of cinema — Alraune. Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were popular subjects during the first years of cinema, the devil and various demons, as well as witches and even giants made regular appearances on screen. Four iconic monsters, however, got their cinematic birth in the Central European film scene that incorporated Denmark, Germany, Austria and Hungary in the span of seven years, between 1915 and 1922. This coincided with the birth of German expressionism and the birth of the horror movie. These four monsters were: The Golem (1915), Homunculus (1916, review), Alraune (1918, 1919) and Dracula (1921, 1922).

The Golem, based on an old Jewish folk tale, was the creation of writer-directors Henrik Galeen and Paul Wegener, and went on to have three adventures in the films The Golem (1915), The Golem and the Dancing Girl (1917) and The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920). While never as iconic as Dracula or the Frankenstein monster, the Golem has continued to pop up here and there for the last hundred years. Dracula was first alluded to in the Austro-Hungarian film Drakula halala (1921), or “The Death of Dracula”, reportedly co-written by Michael Curtiz. It is unclear from the film, however (or at least what we know of it), if the film actually portrays Dracula, or if it is simply the hallucinations of a woman at a mental institution, who believes her music teacher is Dracula reborn. The first actual (if unauthorised) adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel was, of course, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), again co-written by Henrik Galeen. Despite the enormous success of the 1916 film serial Homunculus (review), the title character didn’t really go anywhere — perhaps because there was too much of a resemblance to the Frankenstein monster: a giant artificial man looking for love and purpose in a world that fears and rejects him. There are interesting parallels to Alraune, though, as both she and Homunculus are explicitly described as having been “born” without a soul, and thus cannot understand the difference between good and evil, nor the concepts of love, friendship or empathy. Alraune had a longer span of popularity, but she too fell out of favour as the idea of artificial insemination became uncontroversial.

Alraune is the German word for the mandragoria plant, or mandrake in English. The mandrake root has long used for various medical purposes, from pain alleviation to treating colic, insomnia and even infertility. It is mildly poisonous and hallucinogenic, and can irritate the bowel, causing all sorts of unpleasant side-effects. There’s also a long history of wives’ tales and myths surrounding the mandrake. Partly this is due to the looks of the root – it often resembles a small person, or homunculus. One legend states the the mandrake produces a literally deadly scream when pulled out of the ground. Another that when men are hung to die, they get an erection, and the ejaculated seed that drips into the ground gives birth to the mandrake root. The legend further states that women who copulate with these mandrake roots give birth to women without souls – empty and evil vessels. This is the legend that Ewers utilises in his book. But instead of using the alraune itself, he has his scientist collect the semen of a hanged man, and artificially inseminates a prostitute with it. The result is a woman who does not understand the concept of love and has a life filled with perverse relationships. She is adopted by the scientist, but when she learns about her unnatural origins, she takes her revenge on her maker – this is basically a variation of the Frankenstein theme.

The novel was published in 1911, 12 years after a Russian scientist had successfully artificially inseminated small animals. The concept caused moral outrage in conservative and religious circles in Europe (and America), and as a result the novel became a bestseller. Film critic Richard Scheib at Moria writes that “Alraune is essentially a position paper about the idea of artificial insemination. […] As such, Alraune enters into the debate on the subject with the wild alarmism of a tabloid headline. It is also hard not to see in some of this the embryo of the Nazi take on blood and genetics – with the idea that some people are just rotten, evil and socially inferior according to genetic predestination.”

The idea of artificial insemination was, naturally, an abomination from a conservatively Christian point of view, that one could (or should) create life without the holy union of man and woman was blasphemy. But for patriarchy it was also a highly alarming prospect. For ages, women and their sexuality had been controlled by men through the supposed virtue of childbirth. It was a woman’s duty to society and humankind to produce offspring, and to do so she was morally and in some cases even legally obliged to enter into matrimony, whether she wanted to or not. And as a woman, strictly speaking, didn’t have to be aroused in order to partake in the act of sexual intercourse, women’s sexuality was demonised and stigmatised for centuries, creating for men a powerful control mechanism. But the idea of artificial insemination suddenly gave women a potential liberation from the shackles of sexual tradition — in essence it meant that men were no longer needed for the species to survive — only their semen. And if women were freed from these shackles, it also meant a revolution for female sexuality: women could now finally be masters of their own bodies and urges.

This notion naturally tied in with another strong current in society: the suffragette movement and women’s liberation. This wasn’t only about sexual liberation, but political and economical as well. Neighbouring Finland elected the world’s first female MPs in 1907, Norway gave women the right to stand for election the same year. In 1908 German women were allowed to attend universities and in 1909 French women were allowed to sue their husbands over economic mishandling of the family resources. And one gets a feeling that Ewers didn’t like any of it. So, in his novel, the offspring of a hanged murderer and a prostitute is his ultimate nightmare: a woman who likes to have sex, has it with whom she herself wants and doesn’t apologise for it. Gasp! This woman, liberated from religious, patriarchal and moral norms he paints as soulless, heartless and forever doomed to unhappiness. When Alraune finally learns of her unnatural origins, she avenges herself upon her creator.

Around the time the novel was written there were also other factors involved that left their mark on Ewers’ novel. The idea of social Darwinism was making headway, and questions of human evolution interested scientists and science fiction writers alike. At the same time psychology as a science was slowly starting to form, with Jung and Freud establishing themselves as stars in the field. The question of the hereditary vs the learned, or nature vs nurture, was hot stuff. It was this question that, in the novel, was the starting point for Professor ten Brinken. ten Brinken wanted to prove that from the seed of a hanged murderer and the egg of a prostitute, he could raise an impeccably moral lady.

David Cairns at Mubi writes that “Ewers was an odd character, a devoted nationalist with a fancy for homosexuality and sado-masochism that insinuates tendrils of perversity into all his work. Despite believing Jews made the best Germans, he also got into bed with the Nazis, writing a screenplay about unsavoury martyr Horst Wessel, but by 1945 he had been branded an “un-person”; expunged from the records; forgotten to death.” Ewers also penned the script for the “creaky but influential” 1913 film The Student of Prague, generally considered the starting point for both the horror film genre and German expressionism. The film starred — who else? — Paul Wegener.

To be quite fair, the first Alraune film, the German Alraune, die Henkerstochter, genannt die rote Hanne (from hereon “Sacrifice” for short), was not really based on Ewers’ book. It’s sort of like when you have an Italian film literally called “6 days on Earth”, but translate it as Alien Exorcism (2011) because, you know Alien (1979) and The Exorcist (1973) were really popular films. Alraune was a bestselling book with a lurid reputation, so sticking the root in a title was a great way to get publicity.

There is very little information about the film’s plot online. What little there is seems to be misinformation, based on the assumption that the film follows the plot of the book. In fact, Sacrifice is more of a ghost story about a woman in present-day (1918) Germany whose child falls ill, and she is visited by the ghost of her ancestor, a witch, who shows her that the story of her life is repeating itself. Sacrifice isn’t lost, however, but a (nearly) intact 16 mm print has survived at the Eastman Kodak archives, and has been occasionally screened.

One user at the AMAZING Classic Horror Film Board (which should be preserved at the Library of Congress as culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant) recalled seeing a screening of the film many years ago and described the plot as such: ” this Alraune is about an unhappily married woman whose child falls ill. She learns of the magical mandrake root, which has the power to save the baby’s life. But the woman is then visited by the ghost of an ancestor, who was in the identical situation: she used the mandrake to save her child, but the baby died, and she was caught and sentenced to death for practising witchcraft. The woman decides to ignore her ancestor’s warnings and uses the mandrake. The child recovers, her husband comes back to her, and all is roses and rainbows.” He further writes that the film struck him as “quite ordinary”

The film was directed by Hungarian director Eugene Illés, who spent most of his career in the German film industry. Born as Illés Jenö, he was educated as an engineer, and got his first job in the movie business in 1912 as a cinematographer. He filmed or directed over 120 movies, mostly in the popular genres of action and adventure, between 1913 and 1927, none of which have left much of a mark on history. If he is remembered today, it is primarily for his Alraune connection.

The second version of Alraune has been the focus of much debate, to the point that even the masterminds at the Classic Horror Film Board are confused. Conventional wisdom has it that this was one of the last Hungarian films directed by Mihaly Kertész, who along with Alexander Korda and Mor Ungerleider was one of the creators of Hungarian cinema. The movie was produced for a small company called Phoenix Films, where Kertész was head of production. Kertész left for Germany in 1919, when the Hungarian film industry was nationalised under the short-lived Hungarian communist rule, which was overthrown by the far-right in 1920.

Under the name Michael Kertész he rose to some prominence in Germany with quasi-biblical epic blockbusters, like Sodom und Gomorrha (1922) and The Moon of Israel (Die Slavenkönigin, 1924). The films were meticulously researched for historical accuracy, contained lavish sets, bold camera work and impressive special effects, such as the parting of the Red Sea. They are described by modern critics as fairly dull affairs, though. These German blockbusters attracted the interest of Arthur Warner at Warner Brothers, who brought Kertesz to Hollywood, where he again changed his name, this time to the one he is internationally known for: Michael Curtiz.

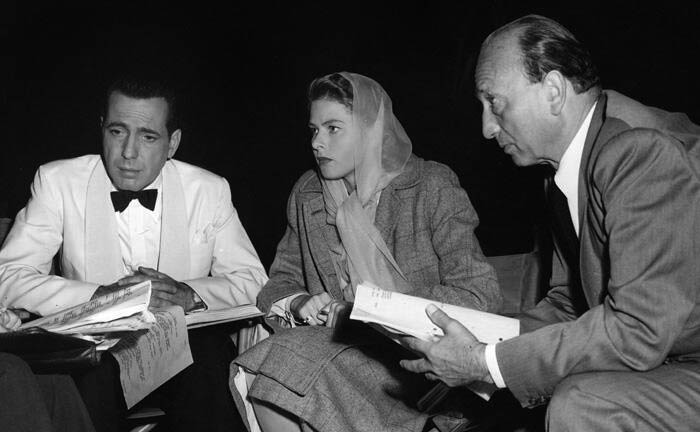

Michael Curtiz, of course, directed films like Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), Captain Blood (1935), Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and of course Casablanca (1942) and Mildred Pierce (1945). He directed in every conceivable genre, including sci-fi, and made two classy low-budget sci-fi/horror thrillers in Hollywood: Doctor X (1932) and The Walking Dead (1936, review). His name is often left out when discussing the great directors of Hollywood’s golden era, despite having directed some of the most successful and critically acclaimed Hollywood films in history, discovered some of the business’ brightest stars and made several Oscar-winning films. The main reason for this is probably that he was such a versatile director and worked in so many different genres that it is difficult to discern a typical “style” for his movies. He also died in the sixties, when the auteur theory was at its height, and didn’t live to see the renewed interest in the Golden Age films.

Curtiz is famous for having discovered Errol Flynn, John Garfield and Doris Day, as well as for turning actors like Olivia de Havilland, Joan Crawford, Ingrid Bergman and not least Humphrey Bogart, into superstars. He is famous for never learning English properly, as well as for being something of a slave-driver on set. He himself, for example never had lunch, as he felt in made him drowsy, and therefore he resented actors that took lunch-breaks, calling the “lunch bums”. While reportedly a kind-hearted man off the set, his work ethic and drive made him blunt and ruthless towards his co-workers, including actors, especially if they were late, lazy or ill-prepared. Despite this, his favourite actors kept returning to him in film after film, as if they realised that in pushing them, he also brought out the best in them. Even when working on big pictures, he was able to make 4 to 6 pictures a year, thanks to Warner setting aside two different film crews for him: while one was filming, the other was preparing the next film, so that Curtiz could jump straight into the action. Curtiz won an Oscar as best director for Casablanca. He passed away in the mid-sixties from cancer.

While he made three low-budget sci-fi films, he is not a household name in the genre, although slightly more revered in horror circles. He is sometimes credited with having co-written the above-mentioned 1921 film Drakula halala, although no definite proof of this seems to exist. However, the film’s director Károly Lajthay and Curtiz did collaborate on a number of other projects, so the notion isn’t far-fetched. And furthermore, Curtiz’ younger brother Dezsö Kertész was cast as the young male lead George.

Now, confusion has arisen in some circles over the fact that some advertising material has Alraune credited with another director, named Edmund Fritz. There’s also mentions in trade literature from the time of an Alraune film being directed by someone called Fritz Ödön. Another anomaly is that the film is given different lead actresses in different sources: some sources have Margit Lux playing Alraune, while others give the role to cabaret and opera singer Rozsi Szöllösi. This has led to speculations that yet a third Alraune film was either filmed or at least planned in 1918. The fact of the matter is that Edmund Fritz was nothing more than the Germanised version of the name Fritz Ödön, so these are one and the same, and Fritz is now generally considered to have been the film’s co-director. Edmund Fritz is something of a mystery to film buffs — Alraune is his only directorial credit, and his only other credits are as an actor in German films from the early thirties, where he appeared with his singing group Fritz Edmund’s Singing Babies, later renamed as the Singing Sisters.

Turns out that Fritz was a cabaret performer and director in Budapest, in the same circles, it turns out, that Rószi Szöllösi moved about in. At the time Szöllösi performed with the Apollo Cabaret, and it is possible that Curtiz spotted her in a sketch where she was performing a female golem. Margit Lux, that has sometimes been credited with playing Alraune, was in fact a more seasoned actress than Szöllösi, so it isn’t that strange that, for example some Hungarian film magazine would make he assumption that she, as the biggest female star of the film, would have the biggest role. She did have a role in Alraune, but not the lead role. Later in her career, Lux was almost robbed of her lead in the afore-mentioned Drakula halala by film journal Kepes Mozivilag. The journal claimed that the female lead was Lene Myl (actually a Serbian actress named Milene Pavlovic), despite the fact that she was almost completely unknown. In the book Expressionism in the Cinema Olaf Brill writes that the magazine “remarked on her ‘impressive appearance’ and and went so far as to say that she would ‘ensure the success’ of Drakula halala“. Brill writes that all subsequent press stories between 1921 and the film’s re-release in 1923 correctly identify Lux as the lead. And to be fair, Kepes Mozivilag also, in the same article, stated that H.G. Wells wrote Dracula. In fact, judging from the gown that Lene Myl is wearing in the production stills that Kepes Mozivilag published, whe probably played one of Dracula’s wives.

But regarding Alraune none of this explains why a cabaret director with no film experience would suddenly become co-director of what must have been a fairly high-profile film, nor why a cabaret singer with little to no film experience would be elevated to lead actress over a tried and tested film actress.

Now, I have this outlandish idea: We know that Michael Curtiz had a knack for spotting talent: he did discover Erroll Flynn, John Garfield and Doris Day. In fact, Doris Day was a singer when Curtiz discovered her, and in her saw something special. What if Rózsi Szöllösi was in fact his first Doris Day? He discovers her at some cabaret and asks her to star in his new film. But, perhaps there is a director at the Apollo Cabaret where Szöllösi worked at the time, and perhaps his name is Fritz Ödön. And perhaps this director is reluctant to let Szöllösi go off and star in some movie — perhaps she is under contract. And perhaps he convinces Curtiz to let him “direct” the film with Curtiz as supervisor in order to bypass her contract?

Whether Michael Curtiz’ version of Alraune was any good is difficult to say, as nobody has been able to dig up any reviews of the film. No copy of the film has survived. But according to what we can glean from press clippings and the character roster, the film seems to have followed at least the broad outlines of Ewers’ book.

There was actually a third version of Alraune at least planned for release in 1919, called Alraune und der Golem. We know there was a script written by Richard Kühle, that combined Hanns Heinrich Ewers‘ novel with the short story Isabella of Egypt by Achim von Arnim — Kühle novelised his script in 1920. It was also naturally inspired by Paul Wegener’s hugely successful Golem films, the second of which had been released in 1917. Swedish actor and director Nils Chrisander was set to direct, and posters had been drawn up. There are several mentions of the upcoming film in trade journals. However, it seems that for one reason or the other, the project fell apart. There has been much speculation over the past century about this version of Alraune, and for many decades it was considered a lost films. But today most film scholars agree that all indications point to the conclusion that the film was never made. It’s too bad, as it would in essence have been the first ever monster bash movie, as it combined two of Germany’s most popular movie monsters at the time, the Alraune and the Golem. But alas, it was not to be. It is quite possible that the filmmakers simply couldn’t secure the rights from Galeen and Wegener, as nothing indicates that they were involved in the production.

A high-profile adaptation of Alraune that is available for us to watch today was finally made in 1928. It too was of German production. It was directed by none other than Henrik Galeen and starred Paul Wegener, once again reuniting these two titans of German horror film. The female lead of Alraune was played by none other than Germany’s biggest female movie star, Brigitte Helm, hot off her astounding success with Fritz Lang’s epic masterpiece Metropolis (review). I personally found that film a tad dull and static, even if both Helm and Wegener were superb in their roles. Read the full review here.

The movie was remade just two years later (review), now in sound, again with Brigitte Helm as Alraune, but this time with character actor extraordinaire Albert Bassermann as Professor ten Brinken. Bassermann is perhaps best known for his role as van Meer in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondant (1940), for which he received an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor. The 1930 film was directed by Richard Oswald, famed for his early, groundbreaking horror film Unheimliche Geschichten. Oswald also directed the quasi-sci-fi film The Tales of Hoffmann (1916, review). While still a master of expressionist lighting, Oswald struggles horribly with the sound aspect of the movie, which comes off a bit like a filmed stage play.

Alraune got a final remake, again in Germany, in 1952 (review), directed by Arthur Maria Rabenalt, and starring Hildegard Knef and Erich von Stroheim. By 1952 artificial insemination was a pretty standardised procedure, and so it was noted even by contemporary critics that the film was made 20 years too late. Variety noted that “in the early 1900s, when the H. H. Ewers novel Alraune cut a swatch in the German-language world […] the very thought of artificial insemination of humans was mentionable only in whispers.” and that “times and sensations change.” Modern critics concur, calling the film drab and archaic. David Cairns at MUBI has explicit problems with the female lead: “A strange nymph like Helm was perfect for this twisted yarn, but the 1952 version suicidally casts a big, rangy, emphatic woman who radiates sturdiness and good health. And she would have to be called Hildegard Kneff (sic), a name with the allure of a hockey puck.”

Science and changing public perception of artificial insemination made any remakes of Alraune impossible, but the male uneasiness over assertive and sexually independent women didn’t disappear anywhere. The dominatrix and the fembot, not to mention alien women from matriarchal societies became staples in science fiction. Oh all the lurid possibilities that the filmmakers didn’t even need to allude to in the British film The Perfect Woman (1949, review), where a scientist builds a mechanical wife for his friend (modelled on his daughter, no less). And in the fifties there were the spider women of Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review), Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), and of course the leather-clad sexual fantasy of the Devil Girl from Mars (1954, review), and that’s just picking a few off the top.

And while the the stigma around artificial insemination has faded, the concept of women having “immoral” births has persisted, be it connected to racial or moral ideas. Demon babies have been a staple since Rosemary’s Baby (1968), and alien offspring have frightened movie-goers since the chestburster burst out of the chest of John Hurt in Alien (1979). One film that was heavily influenced by the ideas in Alraune was the 1976 turkey Embryo, starring Rock Hudson, no less, that tries to say something about something involving … abortion? stem cell research? I honestly don’t know. It revolves around a woman artificially grown from an unborn foetus – and after just two weeks in an incubator she emerges as a full-grown, beautiful woman, complete with a rather inexplicable Nicaraguan accent. She does seem to have a soul, but must feed on infants in order to avoid rapid aging, to her own dismay.

In the 1995 film Species scientists splice human and alien DNA, resulting in a very often nude Natasha Henstridge (or at least that is what the teenage part of my brain remembers of the film) who also matures rapidly, has an obsession with sex and seems to have no qualms about killing men by piercing their skulls with her tongue. So much an impact did Miss Henstridge have on my generation of adolescent boys, that the film spawned two very inferior sequels. The original story was also made into an updated Russian series in 2010. In later years with all discussion on artificial intelligence, stem cells and cloning, artificially made babes with questionable morals have of course become a staple of sci-fi – the many incarnations of Milla Jovovich in Resident Evil and the Alien-Ripley in Alien IV being among the more famous ones. Fortunately, though, we see more and more of these films actually taking the side of the woman in question.

German expressionist films in the 1910s and 1920s had a profound impact on cinema in general and on horror and sci-fi in particular. Films like The Golem and Nosferatu set the tone for Universal’s horror franchise in the 1930s, and one cannot understate the influence these films had on the horror genre as a whole, from film to literature, art and music. Alraune inevitably feels like the forgotten little sister, who was never invited to play tag. There are probably several reasons for this, and it would be too easy to chalk it up to simple misogyny or discrimination. One reason, of course, is that Alraune never was as visually iconic as the other famous monsters. Nosferatu, the Golem, Frankenstein’s creature and Mr. Hyde were all instantly recognisable. But Alraune’s monsterism was external, but internal. And alluring though Brigitte Helm was in her Alraune films, her portrayals of the artificial woman were mere shadows of her mesmerising performance in Metropolis. Influential though they were, Henrik Galeen and Richard Oswald were no Fritz Lang, and nobody was ever able to coax that same magic out of Helm that he once did. And to be fair, even the best remembered version of the Alraune films, the 1928 adaptation, is generally considered to be an uneven and ultimately rather dull affair, relying more on its lurid subtext than its actual content.

When assisted insemination became generally accepted, the whole premise for Alraune’s monstrosity was nullified. While this was in no way the end of misogynistically painted female supervillains, Alraune’s traits migrated to characters, leaving the original behind and forgotten. One might argue that from a feminist point of view, Alraune should indeed remain forgotten. But however problematic the character is, it is also in some sense a shame that nothing more became of the silver screen’s first female horror icon. While the thirties through the sixties did give us a number of cat women, wasp women, 50 ft women, leech women, reptile women, beast women, voodoo women, Mars women, moon women, as well as daughters, brides, nieces and second second cousins of Dracula, none ever became as iconic as Alraune was, for the brief time that her fame lasted. The exceptions were the Bride of Frankenstein and Vampirella; but neither of them ultimately had more than about fifteen minutes on the big screen — Maila Nurmi’s Vampirella naturally became a cult phenomenon on TV, though. In the seventies we had Regan in The Exorcist (1973) and Carrie (1976), who are certainly iconic, but essentially one-offs. And sure, you can count the different incarnations of female monsters in the Alien franchise if you wish. But I would argue that the only female — recurring — film monster that can hold a candle to Alraune is the now so very tired, but still oh so effective trope of the ghost girl from Ring (1998). Please do correct me if I’m forgetting someone here.

A special shoutout this time goes to the guys at the Classic Horror Film Board for their deep insight in all things obscure, and to Gary D. Rhodes for his enlightening work on Drakula halala.

Janne Wass

Sacrifice (Alraune, die Henkerstochter, genannt die rote Hanne). 1918, Germany. Directed ny Eugene Illés & Joseph Klein. Written by Carl Fröhlich, Georg Tatzelt. Inspired by Hanns Heinrich Ewers’ novel Alraune. Starring: Hilda Wolter, Szokol Aoles, Friedrich Kühne. Cinematography: Eugen Illés. Art direction: Artur Günther. Produced for Luna-Film.

Alraune. 1919, Hungary. Directed by Michael Curtiz & Edmund Fritz. Written by Richard Fálk. Based on Hanns Heinrich Ewers’ novel Alraune. Starring: Gyula Gál, Rozsi Szöllösi, Margit Lux. Kalman Körmendy, Böske Malatinszky. Produced for Phoenix Film and Hunnia Filmvallalat.

Leave a comment