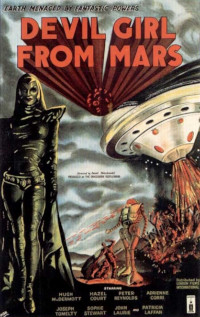

Glorious comic book camp smashes into dull noir drama in this British 1954 cult classic. A must-see for Martian dominatrix Patricia Laffan looking for strong Earth men in her kinky latex outfit, but don’t expect too much. 5/10

Devil Girl from Mars. 1954, UK. Directed by David MacDonald. Written by John C. Mather & James Eastwood. Starring: Patricia Laffan, Hugh McDermott, Hazel Court, Peter Reynolds, Adrienne Corri, Joseph Tomelty, John Laurie, Sophie Stewart. Produced by Edward & Harry Danziger. IMDb: 5.0/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Described by some as the low-point in Scottish director David MacDonald’s career, Devil Girl From Mars is the one film he is remembered for by a broader audience today, a film that is loved by science fiction fans and friends of B movies all over the world, and one that inspired both Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. Sure, this ridiculous science fiction yarn probably wasn’t quite what MacDonald had in mind as his legacy when he worked as an assistant producer in Hollywood for Cecil B. DeMille on films like Cleopatra (1934) and The Crusades (1935). After returning to the UK in the late thirties, MacDonald made a number of so-called quota quickies, and made himself a name as comedy director. During WWII he directed and/or produced a number of acclaimed morale-boosting documentaries, and his career seemed to be looking upward when he returned to feature film with the well-regarded thriller Snowbound in 1949. Unfortunately when it came time for his final breakthrough, the big-budget historical epic Christopher Columbus (1949), everything fell apart. The film was ridiculed by critics and audiences alike, and almost killed star actor and Oscar winner Frederic March’s career. Described by The New York Times as ”an uninspired succession of legendary but lifeless episode of tableaux”and later by Britmovie as ”a long and extraordinarily tedious affair”, this would have been his legacy unless Devil Girl from Mars had come along, since few remember any of the other low-budget movies he made after that, even though some of them are quite good.

Some of the credit for the fact that Devil Girls from Mars is remembered today should go the the wonky robot that has been described by critics alternatively as resembling a refrigerator, a gas pump or a steam cabinet, with stacked styrofoam cups for arms and a light bulb for a head. But let’s not kid ourselves. The real reason is actress Patricia Laffan as the Martian Nyah, decked out in black latex S/M gear and Darth Vader’s cowl and cape.

The film takes place in a remote Scottish inn (this would later become a staple for cheap British sci-fi), where a diverse group of citizens converge. We have Hugh McDermott as the journalist (because all forties and fifties movies had to have a journalist), Hazel Court as the glamorous photo model from London, Peter Reynolds as the escaped convict with a heart of gold, Adrienne Corri as his former flame, a barmaid with an even goldener heart, John Laurie as the whimsical and alcoholic innkeeper, Sophie Stewart as his sensible and stern wife, Anthony Richmond as the annoying kid of the show, Joseph Tomelty as a scientist investigating a supposed meteor crash, and last, and in this case also least, James Edmond as the hunchback servant, because someone has to die in the movie.

Their mundane domestic disputes are interrupted as a flying saucer lands in the moors next door, and produces Nyah, mistress of the night, err, sorry, devil girl from Mars, and her trusty robot companion Chani, who possesses a lethal death ray, and is controlled via a remote control device (and in my opinion looks like a cross between a fridge and a mail-box). Nyah, the icy emissary from the red planet turns out to have great powers of mind control and some other sort of Martian magic, and envelopes the inn with an invisible wall, so that the filmmakers don’t have to build any more sets.

In several long expositional monologues Nyah explains that Mars needs men. The war of the sexes was an actual war on Mars, and naturally the women won. But now the men of the planet are in decline because of degeneration, and the women of Mars need strong Earth men for labour and to provide semen for their Martian-making machines. No, the women of Mars do not engage in baby-making processes themselves, that would be primitive. Nyah was actually on her way to London, but got sidetracked to a small Scottish inn when her flying saucer was damaged while entering Earth’s atmosphere. Now she wants a specimen of Earth male to bring with her to London to show to her superiors as they arrive to harvest. The damaged ship? Not to worry, it is an ”organic, self-repairing metal”. It will soon be up to specs again.

This is the beginning of a rather tedious door-swinging farce where Nyah shows up at the inn and asks for a volunteer to go to Mars with her. Nobody volunteers, so she marches them out to the flying saucer and shows them the awesome powers she and her robot possess, to prove that she doesn’t need anyone to volunteer. She can take whomever she wants by force. However, for reasons never explained, she doesn’t. Instead she lets the men march right back to the inn to “contemplate” her powers (and of course to give the film a chance to get back to the mundane romantic disputes and a few ill-advised attempts at resistance). After a while she dramatically returns to the inn, and the same sequence of events repeat themselves, not just a second but a third time. In between all this is played out a number of dramas with little or no connection whatsoever to the main plot. There’s some business with Reynolds “accidentally” having killed his wife, and is now trying to get in good books with his ex-girlfriend Corri, staying at the inn under an assumed name. That is until McDermott recognises him and tries to call the police but the phone lines are down, so Reynolds escapes, but not really as he is really hiding in the attic. When McDermott is not chasing Reynolds, he is chasing fashion model Court, who has escaped her “life” into the countryside (again, her backstory gets as little explanation as Reynolds’). Then Court discovers Reynolds in the attic, and we’re set up for a triangle drama, but McDermott discovers them, and there’s a fistfight. And in between all this, little Tommy is kidnapped b Nyah and Corri is hypnotised and McDermott volunteers to go with Nyah, but instead of taking him, Nyah turns him into a zombie and sends him back to the inn, and then Tomelty volunteers, but he also returns, and finally Reynolds tries to bargain with his life for the return of little Tommy and … phew! All this is played out in 85 minutes.

The script takes a shot at the one of the most popular sci-fi tropes of the fifties, beside the atom bomb and fear of communism: female emancipation. More often it would be Earth men who who travelled to the moon or other planets where women had taken power and enslaved their men. Here it is a representative of the women of Mars who comes to Earth, which is naturally easier on the budget. I have written more about the so-called ”Amazon Women” subgenre in my review of Cat-Women of the Moon (1953), so head over there for more on the background of this trope.

No doubt, the script itself is the weakest link of the movie. Despite the frantic running to and fro, almost nothing actually happens in the film. This is one of those instances when screenwriters hang a film on a single trope — Martian dominatrix comes looking for men — but never have the time of the skill to turn the idea into a story. Oftentimes, the writers of these quickie exploitation movies had neither experience with nor necessarily interest in the SF, and thus fell back on recycled subplots from other genres to pad out the running time of a film built on a single punchline. In this case it’s the “innocent fugitive” à la The 39 Steps (1935) and “bad girl giving up on life” — in fact, just a year prior Hammer had used the same trope of a “bad girl” seeking refuge in the countryside in the peculiar cloning drama Four-Sided Triangle (review).

So little thought has gone into the film, that screenwriters James Eastwood and John Mather have no idea what to actually do with the character of Nyah once she lands. As Youtube critic Robin Bailes at Dark Corners Reviews points out: Nyah has no reason whatsoever to interact with the villagers. She is on her way to London to pick up “the strongest men on Earth”. She is just there to repair her ship. This doesn’t stop her from turning up at least six times at the inn, each time simply to give one of the men another reason to go out to the space ship. At one point McDermott gives himself up to her, then she brings him back to the inn, for no apparent reason. Minutes later she fetches him back to the ship, only to bring him back to the inn again. Of course, the problem Eastwood and Mather have written themselves into is that Nyah powers are far too great and her task way too small for them to create any sort of drama around. She is impervious to — at least — bullets and electricity, she can disintegrate anyone or anything with the touch of a button, she can telepathically enslave both men and women and she has the ability to travel through the fourth dimension. Not that this last trick has any bearing on the plot, it’s just thrown out there as a bonus fact. Basically, she is just visiting the grocery store, but instead of picking up her potatoes and leaving, she stands there for an hour shouting at them that she could pick them up if she wanted, until someone calls security to remove the crazy lady.

There’s no doubt that Eastwood and Mather have been eyeing Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1951 no-budget gem The Man from Planet X (review). Both films are set in a remote locale in the Scottish moors. Both feature a single alien landing in the back yard of the protagonists. Both aliens have superior technology — both even mention an unknown kind of super-metal — and the power of mind control. Both films even have the ex-criminal subplot, even of the refugee turns out to be a good guy in Devil Girl from Mars. Another clear point of reference is The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review). The way the doors of the spaceship open and the ramp emerging is almost a copy of that film. So is also Chani with his disintegrator ray a throwback to Gort, the menacing monster of said classic. The film even uses the same dissolve trick to portray the effects of the death ray. Nyah also has the same regal bearing as Klaatu as she emerges from her ship. The mind control schtick can also be seen as a nod to William Cameron Menzies’ Invaders from Mars (1953, review) — there’s even a scene of little Tommy watching the UFO land from his bedroom window. And of course, the “Mars needs men” trope was played out in Cat-Women of the Moon. This is all to say that Devil Girl from Mars is on some level a knowing spoof of the genre. The problem here is that it doesn’t quite find the right tone. I admire the fact that MacDonald has chosen to play it straight, but unfortunately the rest of the bumbling script doesn’t match the tongue-in-cheek references.

That said: while this is a jarringly stupid film, it is quite enjoyable. David MacDonald was a talented and experienced director. And the cinematography is really much too good for a film of this ilk, elevating it far above its somewhat stodgy acting and its woeful script. Cinematographer was Jack Cox, Alfred Hitchcock’s go-to cameraman for his British films. Everything takes place during a single night, allowing MacDonald and Cox to enshroud the film in darkness. This is partly a cost-saving method, but it also lends the picture loads of atmosphere. Cox’s chiaroscuro lighting has moments of brilliance, such as when he cuts to a close-up of Nyah’s eyes, leaving only a thin stripe of light — very Bela Lugosi-like. The bare, almost symbolist sets of the moor evoke the Frankenstein movies’ Expressionism, and the scenes at the inn balance between Universal horror and film-noir.

I haven’t found any budget figures for the film, but there is no doubt that there wasn’t much of it. However, MacDonald makes due with what he has and wisely keeps the invisible wall intact during all of the proceedings. However, the special effects are actually better than the ones often seen cheap American B movies of the era. The spacecraft is especially impressive, with its fast spinning outer ring and its blinking lights – although Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant thinks he has identified it as a ”clutch housing with a flywheel still attached”. The robot’s disintegration beam and Nyah’s skills at slowly disappearing before the eyes of the terrified humans are carried out almost just as well as they were in The Day the Earth Stood Still.

The interior of the spacecraft is also very well designed, and considering how campy the film is, it almost comes as a shock when it is revealed. Art director Norman G. Arnold clearly drew inspiration for the design for both the interior and the exterior of the flying saucer from The Day the Earth Stood Still, but there’s also nods to European silent films like Aelita (1924, review) and Metropolis (1927, review). Arnold was a prolific art director with over 100 films to his name, including Masters of Venus (1962), but never seems to have advanced past quota quickies and B movies. Considering the quality of the special effects, it’s surprising that special effects creator Jack Whitehead didn’t contribute to more than a fair dozen films.

I’m going to make a wild guess here, since I haven’t seen it corroborated anywhere. But we know that George Lucas was a huge fan of science fiction as a kid, and he would have been 11 when Devil Girl from Mars was released in the States in 1955, which would have been the perfect age for him to be absolutely enchanted by Nyah. And although it is almost certain that some of the inspiration for Darth Vader’s look came from the villain of the 1938 film serial The Fighting Devil Dogs; The Lightning, it is hard to believe that Nyah’s iconic latex get-up didn’t also stick with him for years to come. Another obvious offspring of Nyah is Tim Curry’s rendition of Frank N. Further in the 1973 play The Rocky Horror Show, and the subsequent film The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) – even down to the accent; ”We nyeed Yearth Myen”.

Laffan’s outfit was certainly racy for the time, even if it isn’t particularly revealing. I have seen no discussion on any of my usual sources about the interesting background of the suit’s designer Ronald Cobb. Cobb seems to be a bit of a mystery to most film scholars and online critics, to the point that some (according to the Retro Nerd Girl) have suggested that “Ronald Cobb” was used as an alias. But in fact, despite the fact that Devil Girl from Mars was his only film credit, Ronald Cobb was a well-known costume designer in the fifties. Cobb was an artist and costume designer who worked for the legendary night club Murray’s Club in Soho from the late forties to the early seventies.

When you see movies from the thirties, forties and fifties, where people enter huge night clubs with big band jazz and dozens of dancing girls in elaborate costumes performing risqué numbers: that’s the kind of club we are talking about. And Murray’s at Beak Street in Soho was the number one spot in London. According to the Murray’s Club Archive: “Within its intimate space, Murray’s offered a unique blend of the racy and respectable. Royalty, film stars, and leading politicians rubbed shoulders with gangsters on the fringes of polite society. Princess Margaret, King Hussein of Jordan, Jean Harlow, Randolph Churchill, the Krays – all were members of this notoriously exclusive Club.” It was also here that the notorious Profumo affair started, when it was revealed in the early sixties that the government minister John Profumo had an extramarital affair with Christine Keeler, one of the showgirls working at Murray’s, who at the same time had an affair with a Russian spy. However racy the club, it was famous for its excellent and extravagant dance numbers, rivalling those of almost any ballet. In particular, the imaginative (and often very revealing) costumes worn by both dancers and waitresses at the club were legendary. Many of these costumes were designed by Ronald Cobb. The Murray’s Club Archive describes them as “an amusing assortment of witty French maid fantasies, macabre mannequins in sweeping cloaks, and startling space-age headdresses. G-strings and period humour abound but Cobb’s bizarre confections of plastic, gauze and body paint are always on the right side of kitsch.” Very little is recorded, or at least available online, about the background and life of Cobb, but his designs are readily available. Murray’s declined in the sixties when more explicit peep-shows and strip clubs began emerging — the death knell sounded in 1966 with the opening of the Playboy Club in London.

Patricia Laffan plays her role straight as a razor, and never ever winks at the audience – one of the reasons, I think, that the film has become such a cult classic is that nobody ever lets on how campy the film is. Actress Hazel Court said in an interview that they had a lot of laughs between takes, but always stayed dead serious on camera. Although fond of the latex material initially, Pat Laffan had quite an arduous time with it during filming. She has said it was very hot to act in, and she had to stay on a strict diet during the week-and-a-half of filming. Once she was in costume, she couldn’t eat or drink anything before they got her out of it, because the slightest bulging of her stomach made it almost impossible to get off. Unfortunately Laffan is stuck with idiotic lines, and one would have loved to see a little more life and intelligence in the character. But Laffan pulls it off great.

As usual with British films, the acting isn’t an issue. Every toddler in Britain gets a classical Shakespearean theatre training and if you haven’t performed in either Hamlet or Macbeth before your 11th birthday, your are routinely thrown into the Thames as no self-respecting parent would have you around as a reminder of the family failure. In other words, even in the lowest-budgeted films of the British movie industry, the acting is at least passable, which is the case in this movie. Most of the characters are bland and uninteresting. Hugh McDermott as the journalist is a poor man’s macho hero, here relegated to ”the other man”. Although she had a supporting role, the most instantly recognisable name in the film is Hazel Court, one of the truly great horror actresses of the fifties and sixties. Playing the photo model from London, Court is perhaps the best actress in the movie, and does her role with charm, sincerity and grace, and hers is the only character that comes off as a real person. While very beautiful in black and white, the green-eyed redhead came off even more ravishing in her later colour films.

Devil Girl from Mars was produced by the New York-born Danziger brothers for their own production company, an outfit that made cheap quota quickies and later TV shows, all while the brothers made a good profit and eventually left the film business in the early sixties, moving into the hotel business and bought into the Cartier jewellery business in Paris. They were also responsible for the sci-fi film Satellite in the Sky (1956, review).

The origins of the movie was a mystery to critics for years, and still is to most. The titles state that the movie is based on a play by John C. Mather and James Eastwood. When I first looked this film up, both Wikipedia and IMDb claimed it was based on a stage play. However, the anonymous author of the The Bela Lugosi Blog, managed a few years back to track down an interview with Mather, conducted by Frank J. Dello Stritto. Turns out Mather was a theatre producer in London, who among other things brought Bela Lugosi to Britain in 1951 to tour with the stage version of Dracula. As a footnote to the interview, Dello Stritto writes that in 1954, Mather worked with the Danziger’s in London producing 26 episodes of the TV series Mayfair Mysteries for Paramount. The show wrapped 10 days early, which meant that the production team had 10 days of paid studio time to spare, and that they whipped up a screenplay in a matter of days. Eastwood is credited for the screenplay, but according the Mather everyone did a bit of everything in the chaos as they wrote, built sets, contacted actors, etc. According to this story, such a play as Devil Girl from Mars never existed. However, it was a common practice for B-movie makers to claim that their scripts were based on plays in order to lend an air of respectability to them. And I’m not sure about this, but it was probably also a technical thing: it is possible that a “based on the play by” credit earned the writers more money than a simple story credit. A play, as is written with distinct scenes, explanations and setups, whereas a story can simply be a note scribbled on a napkin.

Someone on the web also pointed out that the script shares many similarities with the stage version of Dracula – as Nyah entering and exiting a room with people many times, controlling people through hypnosis, looking to snatch away someone of the opposite sex and having control over a henchman – the robot Chani is Nyah’s Renfield. Like Dracula, Nyah is a stern, majestic creature seemingly from another world that passes as human, is clad in a black cape and has supernatural powers. As John Mather produced the Dracula play with Lugosi, this probably isn’t a coincidence.

I have found only one contemporary review of Devil Girl from Mars, from British Monthly Film Bulletin, in which critic LG calls it a “primitive […] effort”, but “quite enjoyable ludicrous, mainly on the account of Patricia Laffan’s Nyah”. The critic continues: “settings, dialogue, characterisation and special effects are of a low order, but even their modest unreality has its charm. There is really no fault in this film that one would like to see eliminated. Everything, in its way, is quite perfect.”

Today, Devil Girl from Mars has a 5.0/10 rating on IMDb and not enough entries at Rotten Tomatoes for a consensus. AllMovie gives it 1.5/5 stars, and TV Guide calls it an ” inferior British retread of The Day the Earth Stood Still“, finding it ” goofy but fun”. In a review for British Starburst Magazine in 2013, critic John Knott repeated the misconception that the movie was based on a stage play, citing it as the explanation for the fact that the film as “only one set” (which isn’t true). Knott continues: “Combine this with slow pacing and a tedious script and you’ve got something that is actually a bit rubbish. So you’re wondering why it’s so iconic. Well that’ll be its ineffable ability to raise a smile. While everyone plays it straight as a die, it still manages to be as camp as Butlins.” Knott gives the film 5/10 stars. In a somewhat cryptic appraisal, David Parkinson at the Radio Times writes: “If proof were needed about the gulf between British and American B-movies, it’s contained in this rare UK contribution to the 1950s sci-fi boom”. Parkinson awards Devil Girl from Mars 2/5 stars.

Independent critics are also divided on the film’s merits. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings has no love for it: “the script for the movie is awful; the dialogue is trite, repetitive, and endless, and the movie never establishes a decent pace”. Sindelar concludes: “I’m sure some people will seek this out in the hope that it will be really bad; I wonder if they would if they knew just how dull it was”. Justin McKinney at The Bloody Pit of Horror found the movie “mildly amusing” and “good for assorted chuckles”. Richard Scheib at Moria and Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant both give Devil Girl from Mars middling reviews. Scheib gives it 2/5 stars, saying “it is neither any better nor any worse than any other science-fiction film produced in the same equivalent budget arena during this decade”. He continues: “To their credit, the actors cast all do a credible job of playing their parts and director David MacDonald does an efficient job of heightening the tensions”. Erickson calls it “more corny than it is incompetent” and notes that “the main joke sustains our interest”. However, Dennis Grisbeck at The Monster Shack writes: “Devil Girl from Mars is a surprising amount of fun to watch There is nothing “wrong” with this film, nothing exceedingly cheap or poorly done”. Finally, Derek Winnert gives the film a solid 3/5 stars, calling it “wonderfully camp and deliriously dreadful”, and continues: “this is the exotic and amazing Patricia Laffan’s finest hour in the movies”.

I find myself just as divided as the above cited critics about this film. On the one hand, it is gloriously, deliriously campy, which should make for 85 minutes of sheer joy – Patricia Laffan, decked out in Ronald Cobb’s delicious S/M outfit, the surprisingly well-designed and animated UFO (a far cry from later hubcaps on strings), and the wonky robot – all of this is ripped straight from a fifties comic book. But it’s as if the filmmakers came up with these wonderful toys to play with, and then had no idea what to do with them. Instead of going all out with either the comic book approach or the spoof angle, screenwriters Eastwood and Mather instead jam the story in place in a meaningless push-and-shove between inn and spaceship. You could cut away everything between the 20-minute and the 80-minute mark, without the viewer having any idea they had lost 60 minutes of film. The sets are the same, the characters the same and the situation exactly the same in the beginning as in the end of the movie. Most of the film’s running time is taken up by the tired and stereotypical relationship squabbles that the writers have inserted as “personal drama”. Then again – the film is well made, a lot better than the bulk of low-budget Poverty Row SF fare coming out of Hollywood at the time. It’s definitely a must-see for any self-respecting SF fan, but it’s the kind of film that’s more fun after you’ve seen it than during. What’s perhaps most irritating is the fact that with a little more time and better handling of the script, this could have been a really great comedy. This is the kind of story that Ealing would have elevated to glorious comedy gold. Imagine Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers, Joan Greenwood and Herbert Lom ducking Patricia Laffan’s latex whip. The Ladykillers with robots and spaceships. The thought is so wonderful it hurts. Instead we are stuck with this film that is … well, it’s quite fun despite its many flaws, but only just “quite fun”.

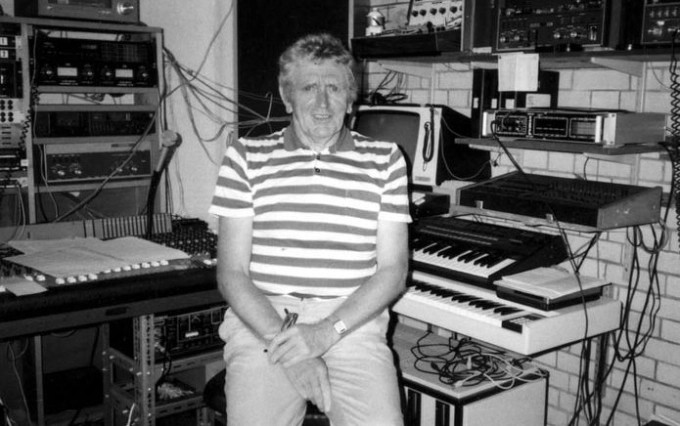

Very little has been written about the music of the movie, but it is actually terrific. Much of the drama and suspense in the film is created by the bombastic classical score which wouldn’t be out of place in some heroic period piece – although it is sometimes at odds with the campy proceedings of the film. Revealing the walking refrigerator to a thunderous roar like the Earth was splitting at it seams is a bit of an overkill. The music was composed by one of Britain’s most prolific and iconic TV composers of the fifties and sixties, working on TV series like The Adventures of Robin Hood, Ivanhoe and The Saint – Edwin Astley. He also provided music for a number of both A and B movies, best known perhaps for the Peter Sellers/Jack Arnold collaboration The Mouse that Roared (1959). Astley occasionally dabbled in science fiction, scoring films like Womaneater (1958), Behemoth the Sea Monster (1959), Kadoyng (1972) and Digby, the Biggest Dog in the World (1973), as well as the TV series The Champions and Department S.

According to the Lugosi blog, Mather moved to Italy after the film’s release, where he established a talent agency catering for American film companies shooting in the country, and later worked at the William Morris agency in London. In 1973 he returned to theatre production with a stage version of the hugely popular sci-fi-flirting British TV series The Avengers (no relation to the comic books). It apparently had extremely impressive special effects and was a hit with audiences, but was cancelled after seven weeks due to high production costs. Mather then retired from show business to write mystery novels. James Eastwood is best known as a writer of spy and mystery novels – in the sixties he wrote a series of books a bout a female secret agent called Anna Zordan, and as a writer of scripts for TV and film, mostly short productions.

Hugh McDermott was a B movie staple, and had a supporting role in Nathan Juran’s H.G. Wells adaptation First Men in the Moon (1962). Peter Reynolds as the escaped convict is equally bland, but functioning, as the escaped convict. He also appeared in the 1960 remake of The Hands of Orlac and the Doctor Who film Dalek’s Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966). Rotund Joseph Tomelty was a stage actor who appeared in a number of A movies as well as a good portion of B’s on both sides of the Atlantic, and also had a role in Timeslip (1955, review). John Laurie was a highly respected character actor who has over 160 film or TV credits, including Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948), but is probably best known for playing Private James Frazer on the TV series Dad’s Army (1968-1977). Sophie Stewart is perhaps best known for playing lead actor Raymond Massey’s wife in H.G. Wells’ daunting epic Things to Come (1936, review). And then there’s Patricia Laffan, Hazel Court and Adrienne Corri, but we’ll get to them later.

Patricia Laffan started out in theatre and worked her way through small characters in film until she landed the role that she is best remembered for, apart from Nyah. She played Emperor Nero’s third wife Poppaea opposite the great Peter Ustinov in the Hollywood blockbuster Quo Vadis in 1951, a film that was nominated for eight Oscars, but sadly came off empty-handed. It won two Golden Globes, though. But Laffan’s career never quite took off, even though she was a well-know face in British entertainment. Devil Girl from Mars was her only appearance in a science fiction film. Laffan passed away in 2014.

Hazel Court had a background in theatre, and made her film debut at the legendary Ealing Studios – makers of the superb Alec Guinness comedies of the forties and fifties – in 1944. She received wide praise for her role as a handicapped girl in Carnival (1946), which lead to a string of leads in films like Holiday Camp (1947), Forbidden (1949), Ghost Ship (1952) and Counterspy (1953). Her real breakthrough came in 1957 when Hammer Films made their first classic horror movie, The Curse of Frankenstein (review), starring Court, Peter Cushing and a then rather unknown Christopher Lee in the role of the monster, and directed by the now revered Terence Fisher. It was at this time she started hopping across the Atlantic, alternating in British and US TV shows and films.

Her next Hammer horror was The Man Who Could Cheat Death, which is often seen as one of the lesser films of the franchise, but which she says she liked very much. The rest of her horror films were all of the none-sci-fi kind, but worthy of mention none the less. She appeared in Doctor Blood’s Coffin (1961), directed by Nathan Juran, memorable for its gory scenes of the title character cutting organs out of live patients. She then went on to star in three of American low-budget master Roger Corman’s most memorable and best-regarded films, Premature Burial (1962), The Raven (1963) and The Masque of Red Death (1964). The Raven was really more of a comedy spoof than a horror film, and starred three of the great masters of horror; Peter Lorre, Boris Karloff and Vincent Price. Court said she had a blast with all the three of them, and especially remembers that they would spend all day trading stories about films they’d worked on. Especially Lorre, she says, was tired of being stuck in villainous roles, and was beside himself with joy at the chance of doing comedy, which he loved. She has often quoted The Masque of Red Death as her favourite film, and it is considered the best of Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, and more often than not as his best film, all counted. This film also starred Vincent Price.

In an interview with Bruce Hallenbeck in 1990 she says that she has no regrets whatsoever for being remembered as a scream queen from science fiction and horror movies: ”I think we’re all so lucky to have done 911 of these things. I think it’s wonderful that I made four classic horror films that are still remembered today. Here I am in my latter years, and it’s exciting to get these marvellous letters from people all over the world.” According to her daughter, Court would receive hundreds of fan letters a year from B movie and horror fans up until her death in 2008. About Devil Girls from Mars Court says: ”Oh, I think it’s wonderful! Even Steven Spielberg looked at it! It was the first, before Spielberg did everything else! It was made for nothing, practically. It’s a piece of film history now. And I think it’s wonderful to be part of’ it.”(Spielberg has said that he drew some inspiration from the movie for his epic Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1979) – and I’m guessing it’s about the spacecraft.) In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver (in the book Science Fiction Stars and Horror Heroes) she says: ”I ran the tape of that film the other day and I really thought it was amazing – for the time, and for what it cost.”

Court moved to the United States permanently in 1961, where she quickly struck up a life-long friendship with Vincent Price, who she thought was one of the most wonderful and friendly people in the world. Price, an avid painter himself, encouraged Court to pursue her hobby as a painter and sculptor professionally. Masque remained her last film role, apart from an uncredited cameo in one of the Omen sequels. She did appear in a number of TV series up until 1975, but focused on her art, and became an established artist. I could go on forever about Hazel Court, but if you’re interested in knowing more about her, I recommend the afore-mentioned interview by Hallenbeck, or a very fun interview at Temple of Schlock.

The third great actress worthy of mention is Adrianne Corri, who plays the barmaid. Not her best role by far, but she does compare favourably to her male co-stars. ”The flamed-haired Adrienne Corri was an actress associated with determined and feisty characters – often reflecting her own up-tempo character”, writes The Scotsman in it’s obituary. Equally at home on stage and in film, Corri, the Scottish-born daughter to Italian parents, got her first screen role in 1949, and can be seen as one of the Christian slaves in Quo Vadis. One of her best roles was as the voluptuous, spoiled girl in Jean Renoir’s The River (1951). To many horror and sci-fi fans Corri is known for her roles in a number of Hammer’s less known horror movies, and for her thigh-high holster-adorned boots as the moon sheriff in Moon Zero Two (1969).

However, she has gone down in movie history as Mrs. Alexander, the victim of one of the most disturbing rape scenes ever put on film, in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). The scene where she is naked, save for her red socks, being raped by Malcolm McDowell, took a whole day to film, and another scene where McDowell slaps her required 39 takes, until McDowell finally told Kubrick that he refused to slap Corri one more time. An IMDb trivia entry claims that Corri ”resented” Kubrick because of her treatment on the film, but there is no evidence for this in any of the interviews I have seen cited. In fact, she knew exactly what she was getting herself into, after two other actresses had quit the role mid-film because they found the going too humiliating. Corri had no qualms about getting naked, as long as she got paid, and said that as a former gymnast she was strong enough to take the physical strain.

According to one story, before the rape scene, she jokingly said to McDowell: ”Well Malcolm, now you’ll get to see that I’m a real redhead”. In an interview she states that Kubrick was a difficult director to work with, especially for women, but that it was fine as long as she put him in his place: ”One has to be very tough with Stanley. He appreciated it.” After filming she had a conversation with Kubrick where he told her that he always lost his socks when doing the laundry. She gave him a pair of bright red socks as a gift, a reminder of her own red ones in the film. Corri’s career dwindled in the seventies, as was often the case with actresses, especially those working mainly in B movies, after they reach a certain age, but she created herself a second career as a renowned art historian. Corri also acted in a fair number of science fiction TV series, including Dr. Who and UFO.

The film was nominally edited by Brough Taylor, but IMDb also lists Peter Taylor as an uncredited editor. Peter Taylor was an up-and-coming editor, who earlier that year had edited David Lean’s Hobson’s Choice. Three years later he would win an Oscar for his work on another David Lean film; The Bridge on the River Kwai. Brough Taylor, on the other hand, doesn’t have a single IMDb credit apart from Devil Girl from Mars. At first I thought that Brough might have been a brother of Peter’s, maybe an assistant trying his hand at editing. Then I read that Peter Taylor’s full name was Peter John Brough Taylor. I suppose he just didn’t want his name on a movie like this. Probably a smart move.

Makeup artist George Partleton isn’t presented with much of a challenge on this film, but he was one of Britain’s top makeup people. He didn’t work much in sci-fi, but to give you the gist of what level of professional he was, I’ll list his four IMDb showcase films: The Bridge of the River Kwai, Lolita (1962), Get Carter (1971) and A Clockwork Orange.

The sound editor on Devil Girl from Mars was a 25-year old film aficionado who was in the process of working himself up in the business. He started as an editing trainee in 1944 and went on to work in both image and sound editing departments for film and, TV, and later worked as writer, producer, director and even composer on a number of films. In 1957 he got the chance to direct his own TV series, and said he had envisioned a grand adventure on the scale of Ben-Hur. As he spoke with his producers as APF, though, they informed him that not only was there no money for such a show, there wasn’t even money to hire any actors. The show would have to be made with puppets. Gerry Anderson, as the former editor was called, was devastated.

However, Anderson became quite adept at the technique he called ”supermarionetting”, where puppets would be controlled by wires inside the bodies. In 1962, after a number of fairly popular puppet shows for APF, the studio commissioned a science fiction show, which became Fireball XL5 – and it proved so popular that NBC bought the distribution rights for USA. This would be followed by series like Stingray, and most importantly Thunderbirds, which became a resounding success all over the world in the mid-sixties. Later he also branched out to live-action series like The Secret Service, UFO and Space: 1999. He was also involved with the sci-fi films Thunderbirds are GO (1966), Thunderbird 6 (1968), Doppelgänger (1969), Invasion: UFO (1974), Invaders from the Deep (1981) and Thunderbirds (2004). Although he never received any major awards for his work on his groundbreaking puppet shows, mainly aimed at children, he was made a Member of the British Order by Queen Elizabeth for his contribution to British animation.

Matte painter Bob Cuff later worked on films like The Day of the Triffifds (1962), First Men in the Moon (1964), The City Under the Sea (1965) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Janne Wass

Devil Girl from Mars. 1954, UK. Directed by David MacDonald. Written by John C. Mather & James Eastwood. Starring: Patricia Laffan, Hugh McDermott, Hazel Court, Peter Reynolds, Adrienne Corri, Joseph Tomelty, John Laurie, Sophie Stewart, Anthony Richard, Stewart Hibberd. Mussic: Edwin Astley. Cinematography: Jack E. Cox. Editing: Peter Taylor. Art direction: Norman G. Arnold. Makeup artist: George Partleton. Sound editor: Gerry Anderson. Special effects: Jack Whitehead. Matte painter: Bob Cuff. Costumes: Ronald Cobb. Produced by Edgar & Harry Danziger for Danziger Productions.

Leave a comment