In the 1930’s science fiction finally made the leap from European screens to Hollywood. More than anything, the SF invasion of the thirties can be attributed to Universal Studios’ resurrection of Victorian horror stories, many of which had a clear SF element to them. The new Talking Pictures brought on a whole new style of acting and made possible the portrayal of more intricate and multi-layered plots. New breakthroughs in special effects, makeup and colour photography broadened the scope of what was possible on film. While Expressionist horror films dominate our Top 10 list, there’s something for everyone, from giant monster movies to politically charged dystopias and juvenile space adventure! What’s your favourite? What did we get wrong? Leave a comment below!

10. Gold

We start off on number 10 with the only German film on the list. This smart, well filmed and very successful 1934 movie marked the beginning of the end for German science fiction before the Nazis banned the genre. Best remembered for its impressive futuristic sets, Gold is on the talkier side. Its secret weapons are German superstars Hans Albers and Brigitte Helm. Albers plays a German scientist who is “recruited” by a Scottish Bond villain to create gold out of lead in a massive underwater nuclear laboratory, while Helm is the estranged daughter of the villain who becomes a potential love interest for the (married) hero. However, in an awkward nod to Nazi sentiment, the hero’s “blood tie” with his wife keeps the relationship platonic. The picture is as much a suspense melodrama as it is a critique of capitalism and the speculation economy, taking the side of the downtrodden worker. Hans Albers is in especially fine form and the performances are outstanding throughout. The cinematography by Fritz Lang favourite Günther Rittau and the impressive sets and effects make this a standout SF film worthy of much greater recognition. The special effects sequences of the movie formed the core of Ivan Tors’ 1953 science fiction film The Magnetic Monster. Director Karl Hartl is perhaps best known for his superb 1937 comedy The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes, again with Hans Albers. Read the full review of Gold here.

9. Doctor X

This early colour film from 1932, impeccably directed by Casablanca director Michael Curtiz, is a stylish and atmospheric old dark house thriller from Warner, with a gruesome sci-fi twist. It’s also an attempt at Groucho Marx-style comedy with Lee Tracy in the lead as a wise-cracking reporter, but Lee’s comedy repertoire isn’t quite up to the task. Fay Wray and Lionel Atwill shine, and the whole thing has the delicious look and feel of a faded pulp magazine.

A series of gruesome murders in a perpetually night-enshrouded city lead the cops to a research department headed by a certain Doctor Xavier (Atwill) and a handful of eccentric scientists. Granted permission by the police to conduct his own investigation into the killings, Doctor X invites all the suspects to his creaky old estate in order to flush out the killer by means of hooking everyone up to a futuristic lie detector machine and re-enacting the murders with the help of his assistant, maid and creepy butler — and for some ill-advised reason, his daughter (Wray). In classic old dark house style, Lee Tracy’s reporter sneaks inside and is subjected to the jitters and finally the affections of Wray. Doctor X is one of a handful of taut, immaculate horror gems made by Hungarian-born Michael Curtiz for Warner Bros. in the early thirties. The two-strip Technicolor lends the picture a murky green and fleshy, faded pink that are ripped straight from the covers of a pulp novel. The latter comes to great effect both when the camera rests on the thighs of Ms. Wray in a bathing suit and in the surprisingly gory Pre-Code finale. While somewhat bogged down by Tracy’s asinine attempts at comedy, the wonderful photography, a tight script, splendid performances and a genuinely creepy ending land Doctor X at number nine on our list. Read the full review here.

8. Cosmic Voyage

Our first and only Soviet SF picture on the list, Kosmichesky Reys is a stunning, costly Russian moon landing adventure from 1936, partly inspired by Fritz Lang’s Woman in the Moon. Thanks to the collaboration of legendary rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, it is also impressively accurate. Aimed at a juvenile audience, Cosmic Voyage is an enjoyable and exciting space adventure movie. Loosely based on Tsiolkovsky’s 1893 novella On the Moon (Na lune: Fantasticheskaya povest), the film follows the moon voyage of an elderly scientist, a young female professor and a stowaway kid, their adventures on the moon and their struggle to return home. Not only is this the best SF film to come out of the Soviet Union in the thirties; it is the best SF film to come out of Europe in the thirties, portraying the shift in the SF power dynamic to happen between the twenties and thirties, as the US gradually took almost sole responsibility for the production of science fiction movies for nigh 15 years.

Cosmic Voyage succeeds thanks to a breezy, fun-filled script, sympathetic characters, great miniature and model work and splendid effects. The weightlessness scenes are impressive and the lunar landscapes atmospheric. The stop-motion puppetry portraying the moon travellers dealing with one sixth gravity on the moon is not quite Willis O’Brien quality, but this lapse is forgivable. There is, as was usually the case in USSR movies, a strong propaganda element, but it’s non-aggressive and good-natured and is more about celebrating the spirit of progress than glorifying the Soviet Union. Sci-fi stalwart Sergei Komarov is grandfatherly in the lead, Ksenia Moskalenko is a dead ringer for Brigitte Helm and Anatoli Gaponenko is one of the least annoying kid actors of the thirties. Read the full review here.

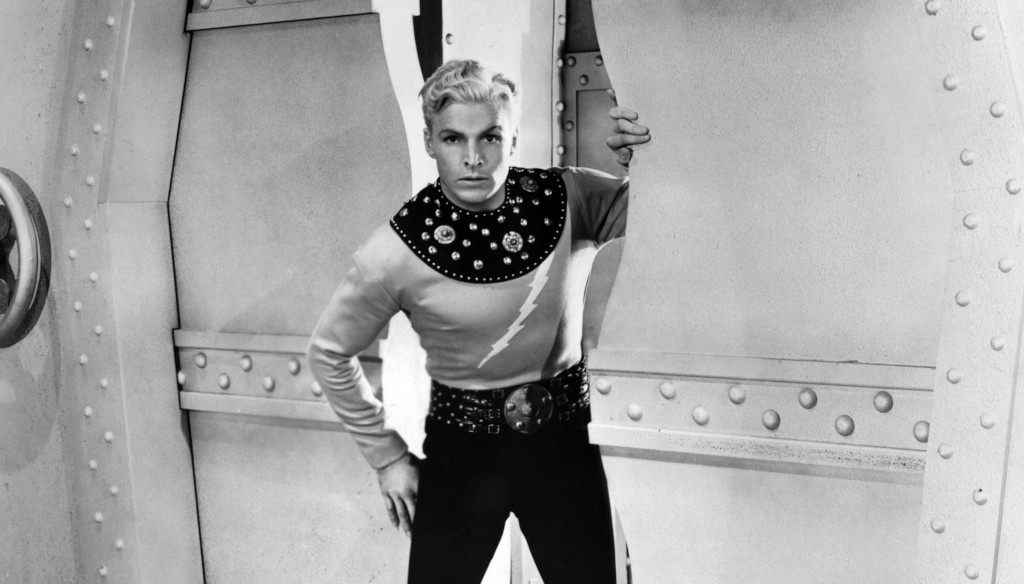

7. Flash Gordon

The 1936 film serial Flash Gordon was the first American space opera brought to the screen. It’s high camp, silly and loads of fun, and boasts good production values for a serial, as well as an unusually imaginative and original script, straight from the pages of the comic strip. That the spaceships are held by visible strings and the dragons look like men in cardboard suits just adds to the fun.

Alex Raymond’s seminal comic strip was so successful that it only took it two years for it to find its way to the movie screen. Told within the serial is the classic story of famous American polo player Flash Gordon and his girlfriend-to-be Dale Arden who hitch a ride with Dr. Hans Zarkov on a space rocket in order to prevent the planet Mongo from colliding with the Earth. Flash goes up against the evil emperor Ming, Vultan of the Hawkmen, King Kala of the Shark Men, and other famous villains, when he’s not battling orangopods, dragons or robots. Made on a fairly sizable budget for a serial, Flash Gordon is a wonderful adventure story, with great action, larger-than-life characters, superb casting and a surprisingly well-crafted script. It’s also immensely silly. Champion swimmer Buster Crabbe portrays a hero who’s not too bright and whose righteous wrath and knucklebone attitude often create more problems than they solve, leaving Jean Rogers’ Dale Arden and Frank Shannon’s Hans Zarkov to think the trio out of several tight spots. Charles Middleton as Ming is iconic, as are Priscilla Lawson as Princess Aura and Tiny Lipson as Vultan. It’s not exactly Citizen Kane, but Flash Gordon is a seminal piece of Americana, and one of the most influential film serials in the history of Hollywood. Perfectly capturing the fun-filled atmosphere of the comic strip, Flash Gordon is a genuine classic. Read the full review here.

6. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

By many considered as the best movie version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s book, this 1931 film resulted in an Oscar win for lead actor Fredric March. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in Paramount’s classic adaptation is beautifully filmed by Rouben Mamoulian and well acted across the board. It also features some stunning visual tricks, such as March’s transformation from Jekyll to Hyde in one single take, done with the help of an ingenious combination of makeup and tinted camera filters. March’s Mr. Hyde is almost simian in appearance, and the actor plays the role with the joie de vivre of a dog being released out to play after being shut in for days. His Hyde revels in the flood of emotions washing over him after ridding himself of the stifling moral confines of the Victorian era. It is one of the smartest takes on the story, and one which actually gives Jekyll a tangible reason for creating his potion, as opposed to most of the other adaptations — either for film or stage — of the era, and one that comes rather close to the reason given in Stevenson’s novella, at that. And one should not forget actress Miriam Hopkins, playing the prostitute who’s locked up as a sex slave for Hyde, showing off some leg action which certainly wouldn’t have passed the sensors after the enforcing of the Hays code three years later. The film is marred by wretchedly banal dialogue between March and lead actress Rose Hobart, and seems somewhat confused about its own moral conclusions. This does not detract from the fact that it is a splendidly crafted horror melodrama which has stood the test of time, landing it in spot number six on our list. Read the full review here.

5. The Invisible Man

The most distinctly science fictional of Universal’s classic horror franchise, this 1933 movie directed by James Whale took the world by storm thanks to the terrific acting of Claude Rains, astounding special effects and a witty script laced with dark comedy. The Invisible Man is considered by some to be the best H.G. Wells adaptation ever made. From the first shot of Claude Rains entering the small inn to escape the blizzard outside, with his upturned collar and hat, swathed in bandages and dark glasses, you know you’re in for a treat.

Nevermind the wonky science or the turgid dialogue between lead actress Gloria Stuart and the backup love interest William Harrigan. The script is a whirlwind descent down the mind of a man driven to madness by power and ambition. It is the darkest and most cynical of all Universal horror films, never flinching from the sort of gleeful evil that would never have passed Hays Code censors the next year. All other actors are redundant: This is Claude Rains’ movie. Never showing his face before the final shot, Rains’ booming, raspy voice and commanding delivery dominate the picture, and his still obvious theatrical mannerisms only works in the film’s favour, enhancing the mad Dr. Griffin’s megalomania. But worthy of mention are also the screeching banshee that is Una O’Connor as the inn’s proprietor and E.E. Clive as the bumbling bobby who utters the immortal line “‘ow can I ‘andcuff a bloomin’ shirt?!” And then, of course, there are the special effects. Audiences in 1933 were blown away by scenes in which a clearly present Claude Rains dressing down to his bare bottoms, but nowhere to be seen, or in which he unwound his bandages allowing them to gaze straight through his head. Even when you know the tricks of the trade, there are still moments in the film which make you collect your jaw from the floor. There’s a couple of glaring plot holes and the picture drags in a few places, but this original Invisible Man instalment is still a classic masterpiece from Universal, and a must-see for friends of horror and science fiction alike. Read the full review here.

4. King Kong

The second film on our list featuring lead actress Fay Wray! When the original scream queen passed away in 2004, the Empire State Building lowered its lights for 15 minutes in her honour. That’s the kind of impact that King Kong had. Larger than life in every aspect, the original King Kong was a juggernaut, as loud, daring and unstoppable as its titular monster, it crashed into cinemas in 1933 and has refused to leave ever since. Willis O’Brien’s revolutionary stop-motion work, a multitude of amazing visual tricks and Fay Wray’s legendary screams make this one of the most beloved and recognisable movies in history, even adding a new word to our vocabulary.

A lot can be said about the film’s shortcomings when it comes to dialogue, characterisation, plot holes, the general narrative scripting and indeed the acting. Much of it is terrible. However, this is of little to no consequence. Like the previous entry Flash Gordon, this is a film to watch for its sense of adventure and fun – plus, obviously, the astounding special effects, backed up by a tremendous score by Max Steiner, amazing sets and mind-boggling trick photography. The action is masterfully directed and King Kong himself is beautifully realised on screen. King Kong set the template for all giant monster films to come, and that the movie is continually being rebooted as special effects make for ever more naturalistic effects says something about the special magic inherent in the original film. From the much-maligned seventies adaptation to Peter Jackson’s marathon love letter to CGI dinosaurs and the latest version Skull Island, they have all been unfavourably compared to the first one. Although narrowly missing out on the Top 3 on our list, Kong can stand tall as one of the most influential movies of all time. Read the full review here.

3. Frankenstein

At number three we have the one film that is arguably an even bigger classic than King Kong. The road from Mary Shelley’s influential 1818 novel to the 1931 Universal film was long and winding – the story having been altered and re-imagined dozens of times in between, in numerous stage plays, earlier films and in the minds of the audiences. Still, when director James Whale’s film premiered, on the heels of Universal’s successful horror story Dracula, it forever cemented the public perception of Frankenstein’s monster its maker and the narrative itself. To this day, when we hear the name Frankenstein we think of Boris Karloff in Jack Pierce’s memorable makeup – regardless of whether we’ve actually seen the film or not.

Frankenstein, heavily informed by German expressionism is a masterpiece of camera, light and sound, which proved that sound films didn’t have to be static and clunky (like Dracula). It’s also a film which takes its monster seriously, as Whale and Karloff were determined to honour the spirit of the novel, reverting the earlier image of the monster as a mindless brute to one in which the creature is a tragic victim of circumstances. The addition of a scene where the monster joins a little girl in floating flowers on a lake is pure genius, as it highlights the fact that the Frankenstein monster is simply a child brought to the world, by no fault of his own, as a grotesque abomination, tortured, hated and hounded from the very first day of his “birth”. The script, loosely based on an earlier stage play, is flawed, but this is outweighed by standout performances by Karloff and Colin Clive playing Dr. Frankenstein. Read the full review here.

2. Bride of Frankenstein

Yes, of course Frankenstein’s younger sister is on the list as well, clocking in at number two. Director James Whale came into the making of Frankenstein during pre-production. Bride of Frankensteinfrom 1935 was his very own beast. Filling it with his subversive, campy humour, the British gay director created an American masterpiece of outsidership and persecution. His “new world of Gods and Monsters” was as close to blasphemy as you could get without being censored after the enforcing of the Hays code, and he got away with it by placing the most egregious lines in the mouth of the wonderfully villainous Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). With a beefed-up budget, a script that he controlled and the addition of two of Britain’s finest actors (Thesiger and Elsa Lanchester) to round out the cast of Karloff and Clive, Whale made what is generally considered one of the best American movies of all time.

Of course, the iconic image of Elsa Lanchester as the titular Bride is one we all know, regardless of whether we’ve seen the film or not, despite the fact that she turns up only at the very end of the movie. And then there’s also that wonderful scene with the Monster and the blind hermit (O.P. Heggie), endlessly parodied, but incredibly moving in the original film. In hindsight, though, Karloff was probably right to insist that the Monster should have remained a mute. The scene with Pretorious’ homunculi is really just a throwaway moment, but contains some of the best trick photography the world had seen, courtesy of visual effects wizard John Fulton. The design of the film overall is wonderful, expanding and heightening the Expressionis roots of the first movie. The Frankenstein franchise would gradually sink into money-grabbing self-parody, with lesser actors taking on the role of the creature, as Karloff refused to degrade the character he had created. But in Bride of Frankenstein it stands at the pinnacle of its evolution, and the film is still the best of all the adaptations. Read the full review here.

1. Island of Lost Souls

This is going to surprise some readers. But yes, Paramount’s 1932 adaptation of H.G. Wells’ novella The Island of Dr. Moreau stands the greatest SF movie of the thirties on this blog. Sadly neglected, this is one of the very few horror movies from the thirties that still freaks out audiences to this very day. This dark, atmospheric and disturbing tale of a mad doctor trying to surgically speed up evolution and turn animals into humans predates the body horror and gore genre with several decades, raising issues not only of animal rights, but also of racism, colonialism and the rising tide of Nazi-fuelled Übermensch ideology in 1932. Director Erle C. Kenton was a studio hack, and never produced anything to match. This film belongs to cinematographer Karl Struss, who creates a dark, feverish atmosphere reminiscent of the nightmarish vibes of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. British Thespian Charles Laughton (husband of afore-mentioned Elsa Lanchester) owns the role of Dr. Moreau, creating one of he most memorable and charismatic villains in movie history. The manimals, led by an unrecognisable Bela Lugosi in one of his finest moments remain a brooding threat throughout the movie, until they finally turn on their master and tormentor in a terrific scene, with Lugosi chanting: “You made us: Not Men! Not Beasts! Part Man! Part Beast! Things! Things!”

Made just before the Hays code was enforces, Island of Lost Souls delves into questions of sexuality, bestiality, evolution, eugenics and religion, in ways that few movies at the time dared. While not gory as such, the picture does not spare the viewer, describing in hints, sound and parables that which it cannot show or say outright. The cries echoing from “The House of Pain” are haunting and the scene where Laughton discovers the claws growing back on the beautiful Panther Woman (Kathleen Burke), vowing to next time “burn away all the animal in her” is deeply disturbing. Lead actor Richard Arlen’s character is inconsequential, and serves merely as a placeholder for the audience. Here, the lost souls are in command. If you have not seen this movie, find it and watch it. It is utterly superb. Read the full review here.

Bubbling Under: Things to Come

I would be amiss if I didn’t mention the most grandiose and costly SF movie created during the thirties; Things to Come from 1936. The movie was a belated answer to Germany’s epic Metropolis, which H.G. Wells called “the silliest of films”, and apparently thought he could better its garbled vision of the future. Based on his own book The Shape of Things to Come, he wrote not one, but something like six screenplays for director William Cameron Menzies. Six, because unfortunately Wells was no screenwriter.

As a futurist, Wells succeeds little better than Metropolis’ writer Thea von Harbou, describing the coming of WWII, which urges a return to Medieval life, with crime barons ruling the ruins Mad Max-style. There’s also a mysterious “sleeping disease” turning people into zombies. With the help of airplanes, an international confederation of scientists, “Wings of the World” arrests all warlords and restore civilisation, ruling the world through violent pacifism, like a world police. In the end, a new world is foreshadowed by the first flight to the moon.

Things to Come cost some 300,000 pounds to make, the equivalent of 1,5 million dollars at the time, making it the most expensive film ever made in Europe (not quite the world, but almost). The money shows: The film looks fantastic, but the story is stale, lacking in relatable characters and delivers its message and its predictions in long-winded speeches meant to hammer home the points. It is a stiff and boring film, but nevertheless deserves a look-see. Read the full review here.

Janne Wass

Leave a comment