(8/10) Lead actor Claude Rains does a tremendous job of not being seen in Universal’s classic 1933 horror sci-fi. The special effects are mind-boggling for their day. Una O’Connor screams and the rest of the cast are able, although their characterisations are written down on the back of a matchbook.

The Invisible Man. 1933, USA. Directed by James Whale. Written by R.C. Sherriff. Uncredited writers: James Whale, Preston Sturges, John Weld, Philip Wylie. Based on the novel by H.G. Wells. Starring: Claude Rains, Una O’Connor, Gloria Stuart, William Harrigan. Produced by Carl Laemmle Jr. Tomatometer: 100%. IMDb score: 7.7/10. Metacritic: N/A.

The early thirties were indeed a time of magic for Universal Studios. In just three years they were able to conjure up four of cinema’s most beloved, successful and influential monsters. Or as Time Magazine put it in 1933: “While other Hollywood producers confine themselves to the humdrum mishaps of prostitutes, millionaires and college footballers, Carl Laemmle Jr’s Universal studio specializes darkly in supernatural pasquinades.” After Dracula and Frankenstein (1931, review) came The Mummy (1932), and in 1933 it was time for The Invisble Man to – not – reveal himself. Seated in the director’s chair was once again Briton James Whale (Frankenstein), but this time the monster wasn’t played by either Bela Lugosi, nor Boris Karloff, but by the relatively unknown British actor Claude Rains – and once again Universal’s casting proved itself a stroke of genius.

As with the other successful Universal horror films, the film was based on a book. Dracula and Frankenstein, were, of course, conceived from the ink of Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley, and although not a straight adaptation, The Mummy bore clear similarities to two stories by Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan Doyle: The Ring of Toth (1890) and Lot No. 239 (1892). The Invisible Man, in turn, was based on sci-fi master H.G. Wells’ 1897 novel The Invisible Man.

Compared to Dracula and Frankenstein, The Invisible Man actually follows the basic plot of its inspiration fairly well (perhaps because Wells was alive and demanded script approval). A mysterious stranger – scientist Griffin – covered from head to toe in clothing and bandages arrives at a lodging house in a small British village, demanding a room and absolute privacy to work on his experiments. As the nosy townsfolk soon discover his invisibility, he flees, and starts to wreak havoc in the countryside. Ultimately he reaches the house of an old friend, Kemp, whom he hopes to make his accomplice. It is revealed that as a side effect of his invisibility, he has become a power hungry madman, seeing himself as a superior being to the rest of humanity, and now plans a reign of terror. Appalled, Kemp secretly notifies the police – and after a showdown with the long arm of the law, Griffin is ultimately killed.

There are some rather big differences between book and film. The book has many layers of philosophical and political discussions, as is usual with socialist Wells, regarded as one of the fathers of the British welfare system. All of them would not fit into a 70 minutes long film, neither were they all suitable for the studio that made it. One that Wells thought was distorted by the film is one of moral – a discussion going back to Plato and his book Republic, in which Glaucon discusses the myth of The Ring of Gyges. The story tells of a man who finds a magical ring that makes him invisible, and uses it to seduce the queen, kill the king and set himself on the throne. Glaucon argues that any man would have done the same – since in his mind morals were simply manifested as the fear of being punished for doing something immoral. A man without that fear (say, because of invisibility or infinite economic, military or political power) would ultimately choose to serve his own interests rather than the common good or any moral guidelines. (Plato disagreed, for the record.)

Wells thought this aspect was lost, since the filmmakers had the invisible man Griffin become crazy because of the drug he used, rather than because of the power he wielded. It is worth noticing that Robert Louis Stevenson had published his own take on the same question just ten years prior to Wells in his best-seller Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). In essence, this is also a story about escaping the fear of punishment by changing your appearance in order to be able to carry out your egotistic desires. And one can’t help but see J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic surrounding the ring of power, that incidentally makes the wearer invisible, and leads him to self-centred actions, as a further exploration of the theme.

The other big issue is money – or more precisely, criticism of liberal economic policies. In the book Griffin doesn’t kill anyone – he steals: clothes, food, jewellery, money. There is a whole chapter in which Wells describes how money disappears from banks, shops, institutions, even ordinary people. Villagers recount how money starts flying around, creeping away out of sight, in the shadows, as if carried away by invisible hands, and nobody knows where it goes. It is hardly a coincidence that Wells uses the image of the invisible hand in describing money disappearing into the pockets of a greedy madman. It was the metaphor created by the economic liberalist Adam Smith in his book The Wealth of Nations (1776) to describe the idea of an ”invisible hand” that would stabilise free markets. Wells attacked the neoclassical interpretation of Smith’s term, the notion that governmental interference with the market was unnecessary, since the ”invisible hand” would magically sort out all the problems. In the book, Wells added the tramp Warner, who is a devious immoral coward, and ends up with all the money Griffin stole – thus becoming rich by no actions of his own, thus pointing out what he saw as the flaw in the neoclassical interpretation of Smith. In the end Warner also ends up with Griffin’s notebooks – in other terms, the means to continue the dishonest amassing of wealth through the ”invisble hand”. The filmmakers cut Warner from the story altogether.

The third theme is one common to many of Wells’ books: the double-edged sword of scientific progress. That science without checks and balances, all head and no heart, may well be destructive in the end, despite all the good intentions, thus echoing Mary Shelley’s thoughts about Enlightenment and the ”good human”. As with most of these films, the filmmakers dumb down this idea to the simple statement of ”he was tampering with things that man should leave alone”, a statement that the sceptic Wells hated. Wells never claimed that there was a limit to what science was ”supposed” to know, but he was adamant that the application of science must never be removed from ethics, rules and humanity (look no further than to his pamphlet against vivisection; The Island of Dr. Moreau).

But all things said, Universal’s The Invisible Man was reportedly one of the few film adaptations of his books that Wells liked. It greatly boosted the sales of his novel in 1933, which he gratefully thanked the film for – and in his autobiography he called it an ”excellent film”. The only really big criticism he had was the way Griffin was portrayed. He was disappointed that the filmmakers had turned him into a madman from the very beginning. In the book it is the invisibility that slowly takes its toll on his mental faculties, thus making it more of a moral tale. The idea being, that under the right circumstances, Griffin could be anyone of us. Director James Whale famously responded that in the minds of a rational audience, only a madman would want to make himself invisible anyway.

Of course all this philosophy wasn’t why horror fans went to see the picture. They turned up for the invisible man. So that’s the heart of the film. It all begins with one of the greatest opening shots in movie history. In the middle of a nightly blizzard, the jovial cackling of a lodging house in the little rural British town of Iping is interrupted when the door is flung open, in comes a gust of wind and snow, and in the doorway stands a mysterious, looming figure with a long coat, a hat, dark glasses and bandages covering his face. The room goes quiet with wonder and fear as he approaches the counter and asks – no, demands that he get a room with a fire, a private sitting room and complete privacy. And his bags picked up from the station with urgency. The man, of course is Griffin, named Jack in the film (Wells never gave him a first name). The landlady is director James Whale’s favourite actress, the wacky Una O’Connor, speaking with a broad, rural Sussex accent, as the other actors as well. This is not just the filmmakers playing it up – Wells actually wrote the book that way. This was surprisingly common literary trope of the day: many late 19th century novels spell out speakers’ accents phonetically, making some of them almost unreadable for someone not familiar with said (sometimes archaic) accents.

But the stranger has an intellectual, urban intonation – and his voice – it is commanding, gravelly, and dark, almost as if it came from some pit of hell, but still has a preciseness, a refinement about it.

Up in his room the stranger paces back and forth – his hat and coat are removed, but all we see are little tests of hair sticking out from under the bandages. We move back to the landlady, Jenny Hall, she is called, bringing his supper. In the future, he says, they are to leave it by the door, and no-one shall enter. Mrs Hall agrees, but – the helping girls forgot the mustard. So it’s back up again, and for a fleeting moment we see that the lower part of the man’s bandages are removed so he can eat – but what do we see? We don’t really know, but there is no face. He instantly covers up his face with a napkin, and shouts for Hall to get out.

This creates commotion downstairs – bandages and all – an accident? A criminal? A lunatic? Rumours spread. Griffin keeps working with strange liquids in his ramshackle laboratory he’s built, pacing, muttering, cursing, throwing bottles. ”There must be a way back! A way back to visibility!” he shouts. Back from what? Invisibility? We do not know. Not until the curiosity of the nosy villagers become too much, and he confronts them: ”You’re all desperate to know, aren’t you?! Well, I’ll show you! Remember, you brought this upon yourselves”. And off go the bandages – and there is no head! Brayton writes: “that shot is simply part of cultural history, one of the many individual shots from a Universal monster movie to end up serving as a synecdoche for not just its film, but its whole genre. To ’33 filmgoers, that was a stunning, never-before-seen triumph of visual effects. “

The villagers flee in fright, and Una O’Connor screams like a stung pig, and then screams some more, and cackles and flails, and almost faints, and really, really plays up the dumb comedy.

The police is called in, and E.E. Clive as Constable Jaffers is perhaps even a bigger buffoon that the rest of the townsfolk, doing a proper ”bush theatre” performance of the dumb bobby, with all its comical implications. This is set in stark contrast with the threats and taunts – and the legendary maniacal laughter of Claude Rains – in one scene as he removes one piece of clothing after the other in full view of the camera – it must have seemed like magic in 1933. Finally only a white shirt remains. ”Put the cuffs on ’em!” someone shouts, whereby Jaffers utters the immortal line ”’Ow can I ‘andcuff a bloomin’ shirt?!” And with that, Griffin is gone, followed only by a trail of destruction. Prams get toppled, pints swept off the bar, a broom flies in the air and hits a bystander on the head, boxes tumble, a bicycle goes off on its own (on a pretty visible track), and even gets picked up by thin air, and thrown at a group of people.

Then we cut to the first addition of the film: Flora Cranley, Griffin’s girlfriend (Gloria Stuart), and Dr. Kemp, his colleague (William Harvey). She is worried about Griffin, and Herbert says he got reclusive, working in secret, on something dangerous, a project. Straight from the start, the screenplay introduces the curious trope of the “fallback love interest”: We know from the moment that Herbert confesses his love for Flora that poor old Griffin is not long for this world. The setup is the exact same one as in Whale’s Frankenstein: A mad doctor caught up in a crazy scheme, the worried girlfriend, and the doctor’s best friend who is also in love with the girl.

And just as in Frankenstein, the rest of the film then completely forgets about this subplot, which bears no significance for the story whatsoever, only to return to it in the very end, when it is alluded that Herbert will now “take care” of Flora. This ploy would appear in almost every mad scientist film where the scientist was basically a goodhearted man gone astray – always the girl and always her secondary love interest, often a friend of the scientist.

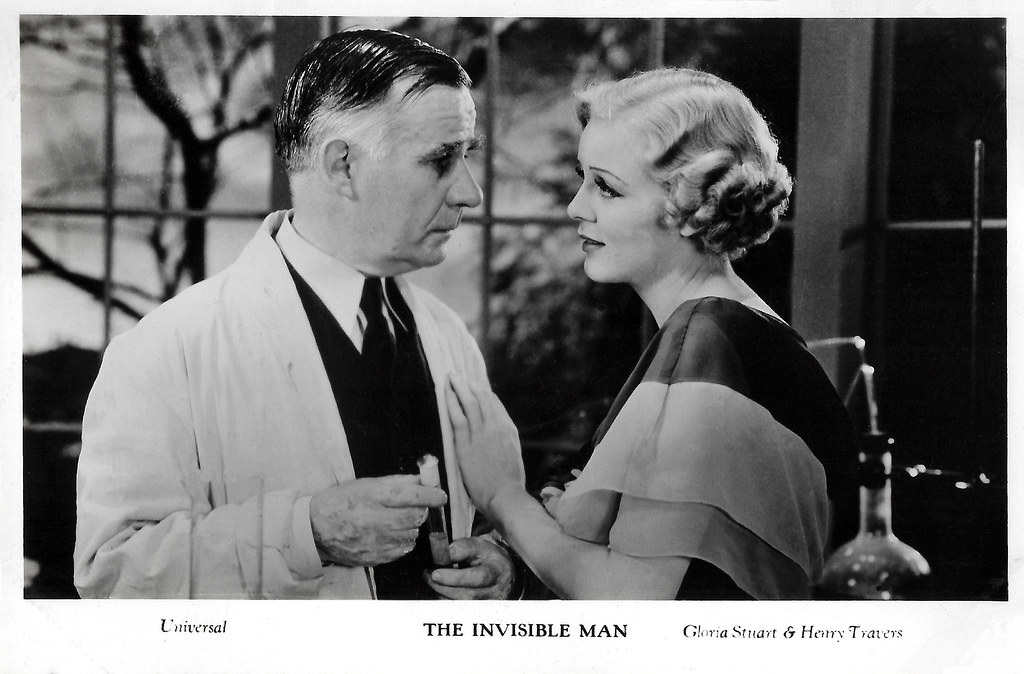

Anyhow, from Flora’s father, Dr. Cranley (Henry Travers), we learn that Griffin had found a rare plant that removed the colour from all it was used on, with the added bonus that the subject went completely cuckoo, and they set out to rescue him from himself.

Griffin later seeks out his old friend Kemp (named Arthur in the film), as he needs a visible accomplice. He threatens to kill Kemp unless he helps him bring about this reign of terror, in one of the film’s most impressive scenes, where the invisible man smokes a cigarette, pokes the fire with a poker, moves around books and matchbooks, and even leaves an impression when he sits in a chair. Kemp secretly notifies the police, but Griffin overhears him and escapes. He later kills Kemp by pushing his car over a cliff, and sends his trademark maniacal laughter as a farewell present.

Hunted by dogs and hundreds of policemen he is finally caught in a barn. And I shall not reveal the ending, even if it is probably familiar to most of you. As we have alluded, it is tragic.

While I noted that much of the intellectual matter of Wells’ book has been drained from the movie, the script isn’t without a depth of its own. Tim Brayton at Alternate Ending writes: “the filmmakers and leading man bring to bear the gloomy, moody sensibility of horror in that period, transforming a quickie literary drama into a haunting meditation on the abyssal cruelty a single man can achieve, when the goodness has been burned out of him”. Bob Graham at the San Francisco Chronicle writes that “The Invisible Man is about the horror of going too far out and not being able to get back”. But the script does also bring back some of the socialist, or at least class, issues that Wells was dealing with, albeit from a point of view of the American Great Depression. Alfred Eaker points out that “Griffin’s ‘bad luck’ comes from poverty, failure to meet societal expectations, imagination, ambition, and drug addiction, all while engaged to Flora who is the daughter of a wealthy inventor father. […] Griffin has another bourgeoisie nemesis in Dr. Arthur Kemp, who also works a ‘good, steady job’ for Dr. Cranley. […] Harrigan is so adept at inspiring our disdain that we wait in eager anticipation for his inevitable murder.”

Apparently it was director Robert Florey who first set his eyes on The Invisible Man at Universal. He had made Murder in the Rue Morgue with Bela Lugosi in 1932, and had been the first director slated for Frankenstein. Universal boss Carl Laemmle Jr. was hesitant, as he wasn’t sure the studio could pull it off. But Florey along with writer Garrett Fort went on to write a draft, which didn’t quite please the studio, and then pulled out when approached by another studio for another project. John L. Balderston, who had adapted both Frankenstein and Dracula for the American stage versions that the films where based on, wrote three different scripts including one with director Cyril Gardner, who was the director-to-be after Florey left. To no avail. At least four or five other writers, including John Huston, wrote drafts of full scripts, but none had the magic Laemmle and the studio heads were looking for. James Whale, who had been on and off the project, wrote a script in which a scientist concocts an invisibility drug to hide a facial deformation, and is driven mad by the potion. That was also rejected. Later star director and writer Preston Sturges wrote a version that was set in Czarist Russia, and split the main character in two – a scientist and his mentally disturbed guinea pig – which was also rejected. Especially Whale disliked it, calling it an ”invisible Scarlet Pimpernel”.

One of the reasons as to why there was so much trouble with the screenplay was that the studio had not only bought the rights to the Wells novel, but also the novel The Murderer Invisible (1931) by Philip Wylie, of later When Worlds Collide (review) fame. And now the studio tried their best to do a hybrid script of the two novels, which was difficult, since the Wylie novel had a lot more fantastic elements than the rather gritty and reality-bound book by Wells. Another problem, as novelist John Weld discovered, was that Wells’ book was out of print, and Universal, who were set to adapt it for the screen, didn’t even own a copy. Weld took matters into his own hands, borrowed a copy from the library, and wrote a very straightforward screen adaptation. Lo and behold, Laemmle liked it. Whale still suggested bringing in R.C. Sherriff, who had written the play Journey’s End, which had been Whale’s ticket to Hollywood. Sherriff made some major contributions; he kept Whale’s suggestion of the madness of the scientist, and added the love story and the part where Griffin kills Kemp in a dramatic car crash, and rewrote most of the dialogue, adding most of the invisible man’s raving mad speeches about bringing about a reign of terror in the world – as well as a good deal of dark comedy, one of Whale’s trademarks.

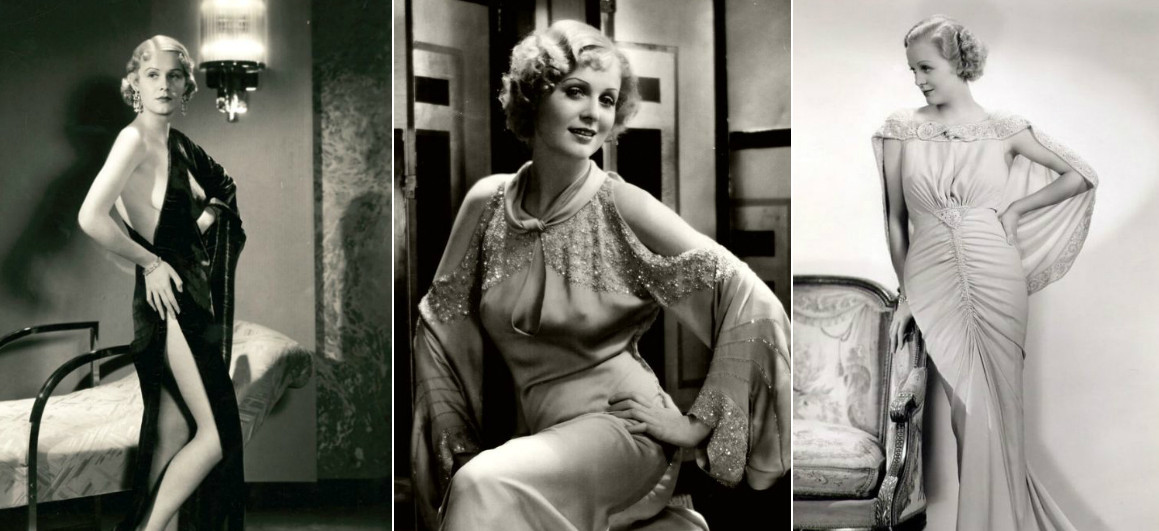

With script completed, and Whale in the director’s chair, it was time for casting. All along it was thought that this would be a reunion for Boris Karloff and Gloria Stuart, who had worked together on Whale’s dark horror comedy The Old Dark House. But salary negotiations between Karloff and Universal broke down, and Whale wasn’t fond of the idea of Karloff as the invisible man from the beginning. A number of actors were considered for the role as Griffin, including Colin Clive, who had played Victor Frankenstein, but he was unavailable. (Bela Lugosi was out of the question, since his thick accent was unacceptable in a role that required a clear and understandable delivery) All the while, Whale himself rooted for British theatre actor Claude Rains, who was now stationed in New York. But the studio was hesitant.

And Universal’s hesitation was understandable. Rains was virtually unknown outside theatre circles, his last film performance had been over ten years earlier, he had never made a talkie, and had little regard for the medium. The Great Depression and dwindling roles on stage nevertheless made him swallow his pride, as it were, as movies were becoming an ever more profitable alternative for actors.

The only reference the studio had for Rains’ acting was a legendary screen test he made for RKO’s film Bill of Divorcement in 1930, where he – unprepared for the camera, and looking to show off, had chosen two pompous monologues to deliver. He read them in an over the top, declamatory style, greatly magnified by the camera, and the test turned out completely disastrous. Rains would later describe it as ”the worst screen test in history”. Legend has it that these auditions were circulated among directors as an inside joke. An often told story is that James Whale would have ”discovered” Rains through these tests, and exclaimed that he didn’t care about the actor, ”but listen to that VOICE!” As is often the case with good stories, this one isn’t true. In fact Whale and Rains were old acquaintances from the stage in London, and Whale was fully aware of Rains’ talents, as well as his wonderful voice – though it is possible that he showed the test reels to the Universal bosses, and might have told them to disregard the performance, and ”listen to that VOICE!” And what a voice it turned out to be. It is largely Rains’ fantastic delivery of the lines that makes the film work. The range, vibrations and personality he brings to the performance makes him almost appear as flesh and blood in our minds, although he is never seen. With a lesser actor, the film would have completely fallen apart.

If the audience was unprepared for the superb special effects, so was Rains. In fact, when debarking for Hollywood, he had only read a rough draft of the script, and was baffled when he arrived and was told that not only would he appear on screen for just half a minute, but he also had to do his acting wrapped in bandages or in an extremely uncomfortable black velvet suit covering his whole body, head, face, and even eyes in some scenes. In some close-up scenes not even his nostrils could be exposed, so he breathed through tubes that ran inside the suit – as well as wearing a headgear that muffled out almost all sound – so he sometimes had to act both blind and deaf. And on top of this, some of his scenes were acted by a stunt man/body double, to which he had to sync his lines. Rains was not a happy camper, and was described as unpleasant, irritable and showy by Gloria Stuart. She nevertheless forgave him, as it was his first big film role, and there was a lot of pressure on him to succeed. ”It was an honor to work with him”, she later said.

Rains later recalled:

”And for five years, five years, mind, I was prating to the Theatre Guild about my artistic integrity. I was so cock-a-hoop about it. My artistic integrity. Then the first day at the studio, James [Whale] brought over some bandages. I asked about them, and he said, oh yes, I was going to be bandaged for most of the picture. And there I had been fighting with the Theatre Guild about my artistic integrity. It served me right.”

Whale also found out the Rains had only seen six movies in his life, and gave him the assignment to see three films a day before he came to Hollywood. Rains learned to turn down his theatrics as time went on, and would deliver superb roles in a huge number of classics, like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939, Oscar nomination), The Wolf Man (1941), Casablanca (1942, Oscar nomination), Passage to Marseille (1944), Caesar and Cleopatra (1945), and Notorious (1946, Oscar nomination). He was also the best thing about the otherwise sub-par Irwin Allen remake of The Lost World (1960), as Professor Challenger. In 1961 he played one of the leads in the brilliantly wacky Italian sci-fi film Battle of the Worlds, directed by cult director Antonio Margheriti.

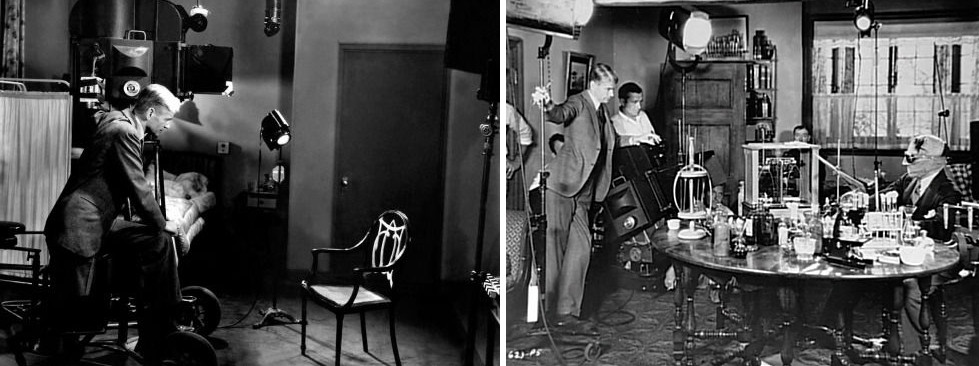

The man who gave Claude Rains so much trouble on The Invisible Man, and who was ultimately the reason as to why the film was such a huge hit, was the head of Universal’s special effects department, John P. Fulton. Fulton had previously worked for the company that originally devised the travelling matte system – a precursor to today’s greenscreen images, known to older readers (like me) as bluescreen. He then worked on nearly every one of Universal’s horror films in the thirties and early forties in some capacity.

Today, when Martin Scorsese can basically put up his camera in his living room and film The Wolf of Wall Street, knowing that his effects department can digitally insert Venice or New York or any location he wishes to, it is hard to comprehend what an enormous task it was for a studio – a ”B-grade” studio like Universal no less, barely saved from bankruptcy by Dracula and Frankenstein – to create the groundbreaking invisibility effects. But back then Fulton, John Mescall and Frank Williams pretty much had to make stuff up as they went along. The technique that we today call greenscreen wasn’t new. Filmmakers like Georges Méliès (A Trip to the Moon, 1902, review) had been using black screens and double exposures for three decades to insert actors in surprising situations or making people seem ridiculously big or small. But making an actor – partly – disappear and leaving his clothes visible was something rarely attempted, especially if you wanted to insert these images seamlessly with normal action, interacting with other actors, and a moving camera. The basic technique that Fulton used had actually been employed once before, by Spanish director Segundo de Chomon in his superb 1909 short film The Invisible Thief (review); the first ever adaptation (sort of) of Well’s novel. However, Fulton & Co took the basic premise and brought it to completely new heights.

As Fulton later described it, it all started with rehearsals of the scenes – with actors interacting with Rains, then rehearsals of the same scene – without Rains. The scene with the rest of the actors would then be filmed, sometimes with elaborate wire effects, making doors and windows open and close, and things floating in the air or moving in a sometimes quite elaborate pattern. Then Rains – or the double – would be taken into a room that was completely covered from floor to ceiling in black velvet, wearing the aforementioned elaborate black velvet suit. On top of the suit he would then be wearing whatever clothes or bandages that were supposed to be seen. Sometimes he was both deaf and blind, and the scene would require as much as 20 or 30 takes to get right. The movements had to be carefully rehearsed as to not give away the illusion. For example, a gloved hand could never be put behind the exposed head, as it would then seem to disappear as well. If his hand was invisible (in a black mitten) he could never bring it in front of his shirt, as it would then appear as a hand-shaped whole through his body. This was especially difficult in scenes where the actor was undressing or removing the bandages from his head. The black velvet suit scenes even had to be done twice, as one take was used as a high contrast blocking print, and another as the actual visual print. Sometimes the background scenes even had to be filmed twice, as in the scene when Griffin stands in front of a mirror and removes bandages. One take had to be done to show the room and the mirror, and another to show the room as reflected in the mirror, and on top of that came the two different shots of the actor – all in all the short scene required four different prints to be merged. On top of that, most of these scenes then had to be painstakingly retouched frame by frame with black ink.

And the result was absolutely stunning at the time, receiving high praise from both audiences and critics, and the film was named by New York Times as one of the ten best films of 1933. The paper’s film critic Mordaunt Hall called the movie “a remarkable achievement“.

Enough praise cannot be given to Claude Rains for his hypnotic voice performance, contrasting between mischievous poltergeist and truly satanic madman, with some of his speeches eerily mirroring those of a German dictator just a few years later. This praise, of course, must also go to Sherriff’s writing and the way Whale framed the shots. ”Power, I said! Power to walk into the gold vaults of the nations, into the secrets of kings, into the Holy of Holies; power to make multitudes run squealing in terror at the touch of my little invisible finger. Even the moon’s frightened of me, frightened to death! The whole world’s frightened to death!” exclaims Rains in his raspy, commanding voice, in an expressionistic shot by a nightly window. The scene still sends chills down your spine.

Sherriff and Whale also imbue the film with their trademark black humour, which makes Jack Griffin a strangely likeable character. He throws false noses at the police, taunting them jeeringly as he undresses, and when he sends Kemp to his death in the car, he politely explains: ”You’ll run gently down and through the railings, then you’ll have a big thrill for a hundred yards or so till you hit a boulder, then you’ll do a somersault and probably break your arms, then a grand finish up with a broken neck! Well, goodbye, Kemp”. In one of the most memorable scenes in the film, Griffin has murdered Kemp and derailed a train, and then we see a pair of empty trousers skipping happily along a dirt road, singing the jolly diddy: ”Here we go gathering nuts in May, nuts in May, nuts in May. Here we go gathering nuts in May, on a cold and frosty morning”, letting out a cheery hoot, and scaring a poor woman half to death.

In contrast with the refined, elegant appearance of Griffin, all the townsfolk are in contrast portrayed as half-wit buffoons, not least the police constable Jaffers, wonderfully played by E.E. Clive, a veteran Welsh stage actor and expert in British accents. The Invisible Man was his first film role, and he would appear in numerous films, often playing comical English stereotypes, in the thirties – including Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review) and Dracula’s Daughter (1936).

The other fix star of the film besides Rains is without doubt Irish veteran actress Una O’Connor. She struck gold with her comical role in the 1933 film Cavalcade, where she was noted by Whale, who then cast her as the hysterically screeching landlady in The Invisible Man. It is the kind of performance that you either love or hate. Whale loved her. Wells loved her. I must admit I have a hard time watching her on screen. God bless the woman, I’m sure she was a wonderful lady, and you have to give her credit – she is a superb comedienne. But for me, it is just too much, too over the top, simply too much broad and loud comedy. Even in a black comedy film like this. My ears just hurt. She would return with the same screeching in Bride of Frankenstein, fortunately in a much smaller role. After the success of The Invisible Man O’Connor decided to stay in Hollywood, where she was cast in numerous other roles, but often portraying a comic relief character like in the Whale films. She also did do straight roles, and acted in serious plays on Broadway. One of her most successful roles was in Agatha Christie’splay Witness for the Prosecution, which ran from 1954 to 1956 and got brilliant reviews, often praising O’Connor for her role. She reprised the role (again a comic relief) as the housekeeper in Billy Wilder’s 1957 film adaptation, which earned six Oscar nominations, including best actor and best supporting actress for the real-life married couple Charles Laughton (Dr. Moreau in Island of Lost Souls) and Elsa Lanchester (the Bride in Bride of Frankenstein). After this film, O’Connor retired.

Gloria Stuart inserts real emotion and humanity into her role as Griffin’s worried girlfriend, although she doesn’t get much to work with – but the scene where she is briefly reunited with him is one of the film’s best. Stuart had previously worked with Whale in The Old Dark House – a star-studded black comedy/horror film, with a cast including Boris Karloff, Charles Laughton and Ernest Thesiger, and in the sci-fi musical comedy It’s Great to Be Alive (1933). She had a decent – if not terribly successful – acting career through the thirties and the beginning of the forties, after dropping out to travel around the world, write, paint and do interior and stage decoration for nearly thirty years. She abandoned movies, she said according to New York Times, after growing tired of being typecast as “girl reporter, girl detective, girl overboard.”

“So one day, I burned everything: my scripts, my stills, everything,” she told The Chicago Tribune in 1997. “I made a wonderful fire in the incinerator, and it was very liberating.”

In 1961 she got her first public art exhibition, which was well received. During the thirties she was also a noted activist, helping many of the exiled German people who flooded the film industry, and became one of the founders of Hollywood’s Anti-Nazi League, as well as the League to Support the Spanish Civil War Orphans. She was also a prominent member within the California Democrats.

In the seventies Stuart returned to acting, first with small walk-on parts in television, later in bit parts in film, as she said the roles that were around for older women at the time were a lot better than the ones she was offered during her heyday. The greatest moment of her acting career came in 1996, when James Cameron cast her in the role as Old Rose in his massively successful historical melodrama Titanic. The role earned Stuart an Oscar nomination for best supporting actress, and suddenly elevated her to gigantic newfound fame. She passed away in 2010, twelve weeks after her 100th birthday.

Forrester Harvey shines as the equally nitwit husband of Una O’Connor. He would later appear in the 1941 remake of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (review) and in The Wolf Man the same year. William Harrigan as Kemp is hammy and bland, and Henry Travers as Flora’s father is passable in his small role. He is most known as the angel in Frank Capra’s popular Christmas film It’s a Wonderful Life.

The film is photographed by the brilliant thrice Oscar nominated Arthur Edeson (The Lost World, 1925, review, Frankenstein), which certainly adds to the refinement of the movie. Heinz Roemheld’s music is effective, where it can be heard, but nothing much to write home about. The editing by Ted J. Kent continues very much in the vein that Whale had established in Frankenstein – we get lots of fast editing, with successive close-ups, zooming by editing – and it works well, if not quite as effective than in the predecessor. Kent would go on to edit many of the Universal horrors.

The film included some extras who were later go on to great fame: future three time Oscar winner Walter Brennan appears as the man whose bicycle takes on a life of its own, and John Carradine in one of his first roles is a townsman who suggests Griffin uses invisible ink. Carradine had a rollercoaster of a career, appearing in John Ford classics like The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and Stagecoach(1939), as well as Z-grade schlock like The Astro Zombies (1969). He became a noted horror actor, and featured in a slew of sci-fi films: Bride of Frankenstein, (1935), The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), The Incredible Petrified World, Half Human: The Story of the Abominable Snoeman, The Unearthly (1957, review), Invisible Invaders, Space Invasion of Lapland (both 1958), The Wizard of Mars (1965), Bigfoot (1970), and The Bees (1978). His last film was the horror movie Buried Alive in 1990. Legendary horror actor Dwight Frye appeared as a local newspaper reporter.

Like the earlier Universal horrors, the plot is distilled to its bear minimum, and the scenes go by rapidly and effectively, which again makes the film seem longer that it is, because so much happen in such a short time. And to their credit, Whale and Sherriff completely do away with the whole business of showing the “good” scientist go through his experiments with good intentions, only to slowly slide into madness, a trope as common as it is tiresome. Instead, as Kenneth Brown at Blue-Ray.com puts it, begin “where other filmmakers of the day would reach by the end of their second act”. Unfortunately this also makes the scenes where nothing much is happening seem a bit dull and draggy. Such a scene is the scientific mumbo-jumbo exposition scene where Dr. Cranley explains what’s going on with Griffin.

In my experience there are two ways to explain the inexplicable in fantastic films. One is not to explain it – just tell the audience to go along. ”Hey, I discovered a potion that will turn me into a snarling sex-crazed and violent beast! Move along.” The other is to base the explanation in some actual science, and then lightly skip over the bits where things don’t make sense. Wells was a scientist, and in the book he gives a lengthy lecture on visibility and invisibility – the fact that what we see is a reflection of light, and depending on how well we can or cannot see through it, depends on its refraction index. We can see through glass, although it is solid. And if glass, which is basically sand, can be invisible, then why not human flesh, if we could tweak its refraction index? And so Griffin does. Hmm, seems like sort of plausible if you don’t think about it too long. What this film does is try to both oversimplify and give a scientific explanation, which is always a disaster. According to Dr. Cranley, Griffin has gotten hold of a ”rare flower that grows in the Himalayas”, which ”drains all the colour of anything it is injected into”. Err, what? What does that even mean? How do you ”drain all the colour” from something? Isn’t colour just reflections of light? And even if you could drain all the colour, wouldn’t it then turn white? Or black?

One of the problems of this film is that all the characters, other than Griffin, become bystanders, and we really don’t care what happens to them. They are given too little screen time, personality and motivation to create an emotional response. Our hero is also our villain, which is certainly interesting, but as he doesn’t seem to have much of a motive other than to generally wreak havoc, that isn’t enough either. So despite all the brilliance, we are left with a strangely impersonal film, that fails to touch us on a basic emotional level in the same way as we feel for Mina in Dracula or Henry Frankenstein or the monster in Frankenstein.

But all in all, despite its flaws, this remains one of Universal’s best horror films, a terribly witty, frightening and funny film all at once, and a true landmark for special effects. It is also perhaps Universal’s most stylish horror film of the era, bar perhaps The Bride of Frankenstein (1935). As Tim Brayton points out, it was the trio of Whale, Edeson and art director Charles D. Hall that “literally invented the Universal house style” with Frankenstein, and all three are back in The Invisible Man. It is a style leaning heavily on German expressionism with its suggestive, stagey sets, unusual camera angles, deep, sharp shadows and eerie highlights. The style also give the Universal horror films a deliberate, rough-hewed clunkiness, a clunkiness that in later years allowed the studio to continue making horror films on shoestring budgets without compromising the visuals all too much. This clunkiness, for the lack of a better world, is one that is absent in the horror adaptations of the major studios of the era, for example Paramount’s stylish takes on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review) and Island of Lost Souls (1932, review).

Brayton continues: “The Invisible Man is blessed with some greatly terrific visual moments, despite having none of Frankenstein’s oozing Gothic atmosphere. The right angle and the right shadow splayed across a cozy English interior, it turns out, is still enough to fill with the whole movie with a jolt of dread: the introduction of Griffin’s inhuman bandaged face at the very start, and a later shot of Mrs. Hall clambering up the stairs and right into an Expressionist nightmare of slicing lines and angles, are surprisingly pure horror for a film which is never particular pure anything.”

The Invisible Man is also partly set in that strange, timeless world of the Universal horror franchise, that retains some of the external trappings of early 19th century continental Europe as inspired by the original Frankenstein movie. The Bavarian-style architecture that would come to dominate the franchise was partly accidental, as the first “Frankenstein village”, or the fictional “Goldstadt”, modified from the novel’s Ingolstadt, was in fact made up of sets remaining from the 1930 film All Quiet on the Western Front. “Goldstadt” would later morph into “Village Frankenstein”, a hamlet some days’ ride from “Vasaria”, the home of the Wolfman and other characters. The Invisible Man is one of Universal’s classic horror films that makes a clear departure from this fictional universe, as the script calls for modern trappings like cars (absent in Wells’ book), telephones and modern bicycles, but the rural setting of Iping seems none too different from Goldstadt or Vasaria. However, The Invisible Man does for the most part operate in a universe outside the Dracula-Frankenstein-Wolfman-cycle. And for all intents and purposes, The Invisible Man updated Wells’ story from the late 19th century to the 1930s, even if the rural setting and the archaic-looking inn and the rural setting does counteract this fact.

I have a slightly schizophrenic relationship with The Invisible Man. It easily qualifies as one of Universal’s five best horror films of the golden era, but I’m not sure if it makes it into the top three. One of the reasons I would like to rate it higher is because Claude Rains is just so good. As far as the classic Universal monsters go, his invisible man sweeps the floor with Lon Chaney Jr.’s lumbering Wolfman (a character I’ve never learned to love) and emerges as a contender to Dracula and the Frankenstein creature along with Karloff’s Imhotep. Technically The Invisible Man is also by far the most accomplished of the Universal horror films: its invisibility scenes are rivalled only by the homunculus scenes in The Bride of Frankenstein. In terms of content it’s also perhaps the darkest and most brutal of the studio’s films, with Griffin gleefully revelling in the death and chaos he causes. This film could not have been made after the Hays Code became rigidly enforced in 1934. R.C. Sherriff’s dialogue contributions elevate the script, especially in terms of the material which is given to Griffin, which is in places sublime.

But then there are the problems I’ve mentioned earlier: the story is drained of most of its intellectual material and simplified to a classic mad scientist romp. Apart from Griffin himself, there isn’t a single well-rounded character in the film — all others are simply placeholders, sometimes given rather bad dialogue, and most of the supporting cast is phoning in its performance. Una O’Connor is the exception, whose histrionics elevate the camp to a level which in my opinion mars the overall darkness of the script. It’s not that I find dark humour inappropriate, on the contrary I find it highly appropriate in a film such as this. But O’Connor’s isn’t dark humour, it’s a tone of loud, garish burlesque that I simply don’t think fits the tone of the movie. I think that James Whale found a better balance between horror and campy humour in The Bride of Frankenstein. However, O’Connor is much loved within the Universal horror fandom, and I know that many disagree with me over her performance in The Invisible Man, so I suppose this is down to personal taste.

Whatever the case, the film was a tremendous success upon its release, both in the US and internationally — in fact it was Universal’s highest-grossing film since the studio’s box-office miracle with Frankenstein two years prior. Not only that, it was almost universally praised by contemporary critics. Over the years Universal released six more or less official sequels, of which The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review) with Vincent Price in the title role is generally considered the best. Still, The Invisible Man avoided the tragic fate that befell so many of Universal’s other monsters in the forties, when the horror franchise regressed into Z movie territory: almost all of the Invisible (X) films retained some measure of quality.

There have been numerous later films “based on” Wells’ novel, but there has never been an actual remake of the 1933 film, nor any real attempt to bring the novel to the screen: most film adaptations have taken the general idea of a man turning himself invisible and constructed entirely new plots around it. Three Japanese movies about an invisible man (tomei ningen) were produced in the forties and fifties, but they shared little with the source novel except the title. A Russian 1984 film called Chelovek-nevidilka (“the invisible man”) was released in 1984, but never shown in the West due to copyright breach. Still, this is probably the theatrically released movie that is closest to an actual remake: it is set in Britain at the turn of the century, retains the central characters from the 1933 movie (even if their functions are reversed — here Kemp tries to use Griffin’s invisibility for nefarious purposes), and some scenes are almost recreated shot for shot — however, the special effects are rather crude compared to Universal’s original. Of the later Hollywood “adaptations”, the best known is probably Hollow Man (2000), directed by Paul Verhoeven and starring Kevin Bacon. A commercial success but a critical failure, the film, again, shared little with the source material. Griffin was brought back again in 2003 in yet another commercial success but critical flop: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a film so badly received that it made Sean Connery go into retirement. However, this film is based on Alan Moore’s graphic novel rather than on the Wells book.

One true attempt to adapt the novel has been made, but for TV. And who else was behind that attempt than, naturally, the BBC. In 1984 BBC produced a six-part mini series starring Pip Donaghy as Griffin. However, the series was poorly received by the public, as it was deemed slow-paced and that the adaptation was too faithful to the written word to make for TV. Several other TV shows have been made over the years, taking the very basic premise of the novel and spinning a new plot around it, not seldom involving espionage.

The Invisible Man is perhaps not quite as loudly celebrated within the Universal monster canon as some of the other classic movies, for whatever reason. It is, however, an almost universally well-regarded film, with an almost impossible 100 % Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes. I have yet to read a negative review of the movie, even if the degree of enthusiasm varies from critic to critic. There are those that hold The Invisible Man as the crowning achievement of Universal’s golden age. While the novelty of the special effects have worn off, the film itself seems to hold up, thanks to a strong script, excellent direction, fabulous acting from Rains and an overall vision by Sherriff and Whale that is seemingly timeless. Laura Boyes at Moviediva calls The Invisible Man the best H.G. Wells adaptation ever made. My vote goes to Paramount’s Island of Lost Souls, but I’d say that The Invisible Man certainly is a contender for the second spot. “It’s the apotheosis of the classic horror film’s formulation of the tragic hero/villain, it’s one of the drollest black comedies, and it’s a film that embraces the fantastic possibilities of the cinema. It’s a true inheritor of the legacy of Georges Méliès“, writes Christianne Benedict at Krell Laboratories, and I’d say that’s a fair summary.

So that’s my take on The Invisible Man, if you agree or disagree, as always, please comment below or on our Facebook page.

Janne Wass

The Invisible Man. 1933, USA. Directed by James Whale. Written by R.C. Sherriff. Uncredited writers: James Whale, Preston Sturges, John Weld, Philip Whylie. Based on the novel by H.G. Wells. Starring: Claude Rains, Una O’Connor, Gloria Stuart, William Harrigan, Henry Travers, Forrester Harvey, E.E. Clive, Holmes Herbert, Dudley Digges, Harry Stubbs, Donald Stuart, Merle Tottenham, John Carradine, Dwight Frye, Walter Brennan. Cinematography: John J. Mescall, Arthur Edeson. Special effects: John P. Fulton, John J. Mescall, Frank D. Williams, Roswell A. Hoffman. Music: Heinz Roemheld. Editing: Ted J. Kent. Art direction: Charles D. Hall. Make-up: Jack Pierce. Produced by Carl Laemmle Jr. for Universal.

Leave a comment