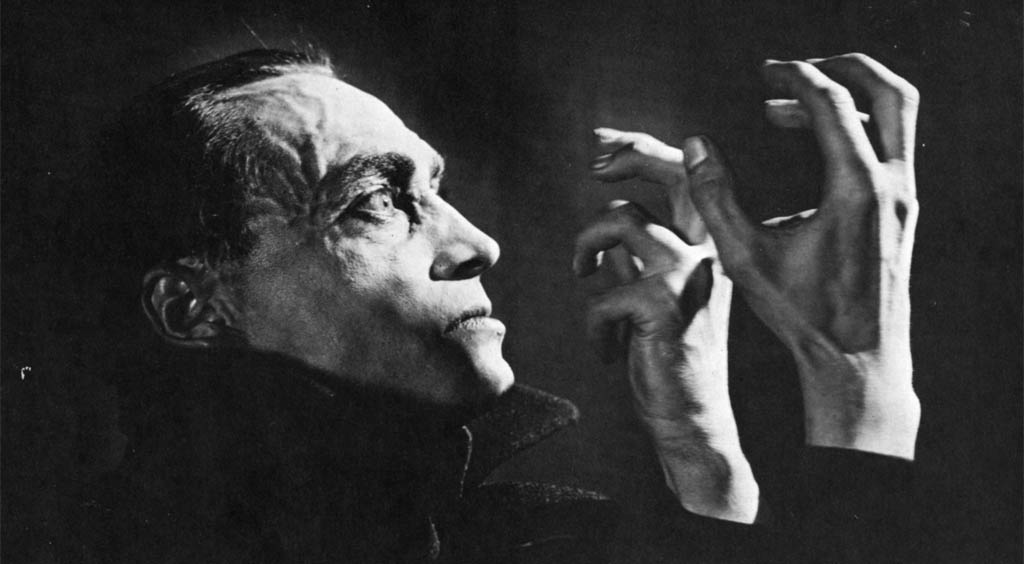

Peter Lorre shines as a mad surgeon who grafts the hands of an executed killer onto the stumps of an injured piano player. Based on Maurice Renard’s novel The Hands of Orlac, the body horror of the book takes a backseat to Lorre’s deranged sexual fantasies about the pianist’s beautiful wife in this 1935 adaptation by horror greats Karl Freund and John L. Balderston. 7/10

Mad Love. 1935, USA. Directed by Karl Freund. Written by Guy Endore, John L. Balderston, P.J. Wolfson, et.al. Based on novel by Maurice Renard. Starring: Peter Lorre, Frances Drake, Colin Clive. Produced by John W. Considine Jr.

1935 was peak horror film in Hollywood. Universal had been leading the charge since 1930 with its string of now legendary monster movies, but Paramount added definite class to the proceedings with stylish outings like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931, review) and Island of Lost Souls (1933, review). Warner had its own franchise going with Svengali, The Mad Genius (both 1931), Doctor X (1932, review) and Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933) and even Fox sort of chipped in with Chandu the Magician (1932, review). MGM, however, didn’t get caught up in the new horror craze. Between 1930 and 1934 it produced only two horror movies, and the first, The Bat Whispers, was really more of a callback to the old dark house mystery thrillers popular on Broadway in the twenties. The only real contender in the new style of horror that the studio put out was the classy 1932 Bela Lugosi vehicle White Zombie. In 1935 Universal churned out a number of high-quality horrors like Werewolf of London, the Lugosi-Karloff team-up The Raven, and last but not least Bride of Frankenstein (review). Columbia produced one of its very best scary movies with yet another Karloff film, The Black Room. Deciding it wasn’t going to sit out all the fun after all, MGM greenlit their own horror thriller, Mad Love.

The movie finds the creepy genius surgeon Dr. Gogol (Peter Lorre) madly in love with Paris-based stage actress Yvonne Orlac (Frances Drake). Gogol is devastated when he learns she is married to the famous pianist Stephen Orlac (Colin Clive), and they are about to move to Britain together. On his way to Paris, Orlac is the victim of a train accident, resulting in such damage to his hands that doctors see no other option than to amputate. Yvonne, realising that taking away his music would be like killing her husband, rushes Stephen to Dr. Gogol, who manages to graft the hands of newly guillotined knife-throwing murderer Rollo’s (Edward Brophy) hands onto Orlac’s arms. However, Orlac fails to re-learn playing the piano with his new hands, and instead realises — to his horror — that the hands are still able to throw knives with deadly accuracy. Not being able to play, Orlac’s finances dwindle and soon the couple is threatened with eviction. As a desperate last resort, Orlac seeks out his estranged stepfather (Ian Wolfe), who scalds him for choosing music over going into the pawn shop business with him. Angered by his stepfather’s refusal and insults, Orlac unconsciously throws a knife in his direction, luckily without harming him. Mortified, Orlac is now convinced that the spirit of the dead murderer resides in his hands, and confronts Dr. Gogol with his worries.

Dr. Gogol’s sexually possessive obsession with Yvonne is so severe that he even has a wax figure of her in his apartment, which his dotty drunk housekeeper Francoise (May Beatty) dresses and brushes. Half in jest, Gogol sees the wax figure as the Galatea to his Pygmalion, and imagines that his love will make it come to life, a notion that sets up the final scene of the film when Yvonne is trapped in the house with the murderous Gogol and the wax statue.

So when Gogol hears of Orlac’s delusions regarding his hands, he decides to use his patient’s unstable mental state to his favour. Using the same knife that Orlac threw at his stepfather earlier (which carries Orlac’s/Rollo’s fingerprints), Gogol kills the pawnshop owner. He then lures Orlac to a secret meeting with the resurrected “Rollo”. In the film’s most famous scene Dr. Gogol is disguised in a large neck brace, dark glasses and a hat, and spitting his crazy lines through clenched teeth, he convinces Orlac that he is Rollo, and that Dr. Gogol has re-attached his chopped-off head to his body, and that his hands live on to do their murderous work through Orlac. Devastated, Orlac turns himself over to the police. Of course, with Orlac now out of the way, Gogol hopes to get Yvonne for himself.

Yvonne, unaware of the danger, seeks out Gogol for help. Gogol, of course, is not home, and Francoise, drunk as a skunk, believes that the wax statue has come to life upon seeing Yvonne in the flesh. In a sly reference to Universal’s The Mummy (1932), which shares writer and director with Mad Love, Francoise staggers out in to the streets, maniacally laughing that “It went out for a little walk”. Yvonne first discovers the wax figure in Gogol’s living room, and then hears the doctor himself return home, triumphantly talking to himself about what he has done. Yvonne hides, now realising she is in mortal danger. Still, after some mix-up between the real Yvonne and her wax bust, the now completely deranged Gogol becomes convinced that if he can not make Yvonne love him, he must kill her, citing a poem by Oscar Wilde: “Yet each man kills the thing he loves”.

Back at the police station a nosy comic relief reporter (Ted Healy) realises that something doesn’t add up in the murder case — but will he get to the truth, and can he convince the police in time to save poor Yvonne from the murderous hands of the deranged Dr. Gogol? And will those newly-found knife throwing skills of Stephen Orlac play a part in the movie before the end?

I am fairly convinced that Mad Love was the pet project of German cinematographer-turned-director Karl Freund. Freund, widely regarded as one of the greatest cinematographers in history, had worked with most of the German greats during the silent era. He was a cinematographer on films like Fritz Lang’s proto-noir The Spiders (1919) and Metropolis (1927, review), and upon his arrival in the US he set the tone for Universal’s horror franchise with Dracula (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) and turned to directing with The Mummy in 1932. His Hollywood directing career wasn’t long, and Mad Love was his last effort, although he kept working as a cinematographer up to the 1950s, when he became the principal cinematographer for the TV show I Love Lucy — rather far removed from his Expressionist background.

Mad Love is loosely based on the 1920 novel Les Mains d’Orlac, or The Hands of Orlac, by pioneering French SF writer Maurice Renard. But perhaps even more so, it is inspired by the 1924 silent film The Hands of Orlac (review), directed by Robert Wiene and starring none other than legendary horror actor Conrad Veidt. Karl Freund would most certainly have seen this minor masterpiece of Expressionist horror, and must have had an urge to give it a go on US soil. The Hands of Orlac did have a limited US release, but was probably not particularly well known to the general audience.

Luckily for the screenwriters, The Hands of Orlac was one of the very few of Renard’s novels that had been translated to English in 1935, and screenwiters Guy Endore, John L. Balderston and P.J. Wolfson worked off the 1929 translation by Florence Crewe-Jones. Balderston, of course, is well known as one of the primary screenwriters of Universal’s horror franchise, and had worked with Freund previously on The Mummy.

As stated above, Mad Love plays rather fast and loose with the source material, more in terms of additions than actual changes. While I have not yet been able to get my hands on the book, synopses seem to indicate that the 1924 film version was surprisingly accurate with its adaptation. Both the novel and the silent film place at their central premise Orlac’s slow descent into madness, as he is manipulated to believe that his mind and soul are being overtaken by the spirit of an executed murderer through his transplanted hands. The book is essentially a crime mystery thriller, with the final reveal being that it was all an elaborate deception by criminals trying to swindle Orlac. It even turns out that the executed man whose hands Orlac had been gifted with was in fact no murderer at all, but had been framed by said criminals and wrongfully executed. But along the way it does, like many of Renard’s other novels, explore ideas of the relationship between body, mind and soul — how much of one’s personality resides in one’s body image, and questions of where the soul is actually located. Does it live in our brains or in our hearts, or is it equally distributed throughout our entire body? What implications would that have? And of course, there are a number of ways one can interpret the theme of a pianist’s loss of his hands, and in essence his livelihood. A Freudian reading would most certainly go for metaphors of castration. The silent film, about a man who suddenly becomes a stranger to his own body, released as it was in Germany between the two world wars, could be read as a metaphor for a people feeling estranged from their home country. The list goes on.

It is probably no coincidence that Orlac’s hands don’t feature in the title of the 1935 film (even if it was released as The Hands of Orlac in the UK and with similar titles in French- and Spanish-speaking countries). No, the mad love referenced in the title is Dr. Gogol’s love for Yvonne. And Dr. Gogol wasn’t even a character in either the novel or the silent film, but was completely made up by plot scenarist Guy Endore. When the original story draft was written, Peter Lorre had not yet been cast. When MGM had secured his loan from Columbia, John Balderston was brought in to rewrite the script, specifically adapting it for Lorre. I’m speculating now, but I suspect that Gogol wasn’t originally intended as the main character, but that MGM expanded the role after securing Lorre: this was his first Hollywood film after arriving to the US on 1934. Hungarian-born Lorre was already an international movie star, having taken the audience by storm as the child murderer in Fritz Lang’s M (1931) and having appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). MGM was now launching this much-talked-about actor in Hollywood, and this featured heavily in the movie’s advertising. Posters advertised Lorre as “the face of 1,000 thrills”, clearly setting the actor up as a successor of the prematurely departed Lon Chaney, “the man of a thousand faces”.

And this is Lorre’s film. The screen is filled with close-ups of his tortured face in Freund’s and cinematographer Greg Toland’s Expressionist lighting, and he has been given a slew of quasi-poetical monologues, sometimes delivered almost directly to the camera. It is beautifully opportunistic, and a wonderfully shrewd coup by MGM. The sexual subtext is barely hidden, with Gogol’s urge to possess Yvonne, a woman he barely knows but has an unnatural fixation on. In a way, his wax doll of Yvonne, the one who loves him, the one who is submissive, whom he can dress and caress as he sees fit, is more real to him than the actual object of his infatuation, who in contrast seems like a distorted version of his imaginary sex doll. Freudians would have a blast analysing this movie’s themes of sexual repression, the sexual-possessive urge, followed by rejection, ultimately leading to the need to destroy the object of desire, perhaps out of an unconscious sense of shame (why can I hear Slavoj Žižek’s voice when I write this paragraph?). But Lorre doesn’t need words to explain all this, it is all there in his face, just like Conrad Veidt completely carried The Hands of Orlac. (Oddly enough, Lorre and Veidt never appeared together in a film in Germany, but made two together in the US, All Through the Night and Casablanca, both released in 1942. You could argue that both actors appeared in F.P.1. Doesn’t Answer [1932, review], but Lorre was in the German version and Veidt in the English version.)

Studio hack Chester Lyons was assigned as cinematographer for the film, but Karl Freund insisted on getting Gregg Toland, and was able to secure him for “eight days of additional filming”. However, Freund and Toland apparently didn’t quite get along, according to Frances Drake: “Freund wanted to be the cinematographer at the same time. You never knew who was directing. The producer (John Considine Jr.) was dying to, to tell you the truth, and of course he had no idea of directing.”

Gregg Toland later went on to become cinematographer for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), and film critic Pauline Kael has noted the many similarities in the two films’ style, lighting and cinematography. Orson Welles himself has said that Toland more or less taught him how to direct a movie while making Citizen Kane, and Kael theorises that Toland in turn passed on what he had learned from Freund during the making of Mad Love. Kael also picked up on a number of similarities between the films’ sets, look and props.

Kael, the famously zesty critic, did not like Mad Love, however, calling it “a dismal static horror movie.” In a rebuttal to Kael’s claim that Welles had copied the look of Mad Love, Peter Bogdanovich stated that it was “one of the worst films he had ever seen”. Well, my good Mr. Bogdanovich, I have a number of films to make you change your mind on that one …

At the time of the film’s release critics praised Lorre’s performance, with Charlie Chaplin calling him “the greatest actor alive”, although Chaplin seems to have said that about at least a dozen actors over the years. Granted, they were not all alive at he same time. Still, the film as a whole fared a little worse with critics. Hollywood Reporter wrote that it was “neither important or particularly compelling … falls right in the middle between Art and Box Office”, while The New York Times stated that “Mad Love is not much more than a super-Karloff melodrama, an interesting but pretty trivial adventure in Grand Guignol horror”. The film failed to recuperate its 400,000 dollar budget at the box-office, bringing in around 365,000 dollars worldwide.

Lorre is madly brilliant (hammy, but brilliant) and Freund creates an Expressionist atmosphere of a reality that is slightly off-kilter, inhabited by mirrors and shadows. The film is set in that pseudo-European turn-of-the-century-cum-thirties gloom so indicative of the horror films of the era. While nobody expects elitist film critics like Kael and Bogdanov to heap praise on a B horror about transplanted hands, some of the later unreserved praise for the movie also feels overstated. Only the Cinema calls it “a stunning work of baroque horror, a bizarre masterpiece”, and Nate Yapp at Classic-Horror writes that Mad Love is “a black pearl of horror genius”, and praises the “masterful script”. Still, I can agree with Derek Winnert that it is a “thoroughly intriguing, involving and enjoyable […] film”.

My reservations regarding Mad Love may be coloured by the fact that I am a huge fan of the silent 1924 version, and especially Conrad Veidt’s frenzied performance as Orlac. It’s the psychological horror inside Orlac’s mind that makes that film so memorable and indeed quite unique among scary movies, while Mad Love reduced this aspect to a mere red herring. Fantastic as Lorre is, by focusing on Gogol, the screenwriters essentially turn Mad Love into a rather clichéd mad scientist story, the likes of which there are thirteen in a dozen. The whole subplot involving the wax figure, while intriguing, is wholly inconsequential, and the film would have worked just as well without it. More than anything, it feels like a clumsy attempt at surfing the coat-tails of Columbia’s success with Mystery of the Wax Museum, released a year earlier. May Beatty’s inclusion as the inebriated comic relief character, in turn, is a ripoff of Una O’Connor’s memorable turns as a nutty banshee in James Whale’s The Invisible Man (1933, review) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review), both of which Balderston co-wrote. If I felt O’Connor was irritating in those films, Beatty is doubly so in this one. At least those two didn’t stoop to the abysmal low-point of including a drunk as the comic relief just because drunks are “funny”. Apart from the reference to The Mummy, Beatty has no good lines or jokes, and is in no way memorable, as O’Connor at least was.

All this does not mean I don’t like the picture. As Kevin Lyons puts it at the always recommended EOFFTV: “Though clumsily plotted […] and burdened with some tedious comic relief courtesy of nosy American reporter Reagan, Mad Love has much to offer, notably the many macabre subtleties; a cake seen at the beginning of the film is decorated with an ornamental guillotine, for example, or the alabaster ‘hands of Orlac’ that sit atop Orlac’s piano. It also benefits enormously from Lorre’s chilling and persuasive performance as the ambiguous Dr Gogol, at once monstrously sadistic and yet seemingly capable of genuine affection and tenderness.”

Colin Clive is one of my favourite actors, and I think he does a good job at playing Orlac. I don’t think he can hold a candle to Veidt’s performance, but that’s not really criticism toward Clive, as his Orlac is a very different role. In a sense, Lorre has taken over Veidt’s role in the picture. I have written extensively about Clive for example in my review of Frankenstein, so please head over there for more information.

The jury seems to still be out on Frances Drake’s performance in the movie. Those who really like the film also praise Drake’s performance, while others have complained about her histrionics. I think Drake is certainly at least an entire class above your average B movie damsel in distress, and if she hulks and wails herself through the script, I’d say it’s the script and not the actress that is at fault. Drake got the part at the last minute when Virginia Bruce backed out of the movie. Drake was under contract to Paramount at the time, but on loan to MGM, as Paramount wasn’t able to find suitable roles for her.

Frances Dean, though born in the US, has no problem appropriating the British accent of the film, having been born into a reasonably wealthy family and spent her youth in schools in Canada and Britain. When the stock market crashed in the US in 1929, her family’s assets quickly melted away, and at 17 she had to start working to support herself while living in London with her grandmother. She started her career on stage as a dancer in musical comedies and then made a few films in the UK on the advice of a friend who told her films paid better. She returned to the US in 1934 and secured a three-year contract with Paramount, who changed her last name to Drake, as her real name was too close to actress Frances Dee’s. Today she is primarily remembered by the horror film community for her outings as damsel in distress in Mad Love and The Invisible Ray (1936, review), opposite Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. Mainstream audiences might remember her for playing Eponine in the high-profile adaptation of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, alongside actors like Charles Laughton and Fredric March, or as a supporting actress in 1939’s It’s A Wonderful World with Jimmy Stewart and Claudette Colbert. She also had a memorable turn as the femme fatale who lures away Robert Montgomery from Joan Crawford at the altar in MGM’s Forsaking All Others (1934). She was pressured into leaving the show business by her husband, the British aristocrat Henry Howard, when he came into his inheritance in 1942 and her income was no longer needed to support the family. Howard disapproved of her acting career.

Gregory William Mank writs about Drake in his book Women in Horror Movies, 1930s: “There was that mixture of Victorian beauty and arch personality … the exotica of those giant hazel eyes, topped by those long, tapered, almost outer-space eyebrows; even though her horror roles were sympathetic, there was a sly, femme fatale allure about her that could easily unhinge the sensitivity (and lust) of the horror stars.”

One actor I haven’t mentioned is Keye Luke, who has a sizeable albeit redundant supporting role as Dr. Gogol’s assisting surgeon Dr. Wong. It’s always great to see a picture from this era where nothing is made of the fact that one of the characters is Asian-American.

Born in China in 1904, Luke grew up in Seattle and initially moved to Hollywood to work as an artist — he is perhaps best known in that capacity for painting several of the murals at Graumann’s Chinese Theater and for designing one of the posters for King Kong (1933, review). He was soon attached as a technical adviser on a number of films featuring Chinese or Asian-American elements, and made his acting debut in a small role in 1934. His breakthrough came in 1935, not because of Mad Love, but thanks to the fact that he secured a role as detective Charlie Chan’s eldest son and sidekick Lee Chan in Charlie Chan in Paris. He reprised the role seven times, but withdrew from the Charlie Chan series when lead actor Warner Oland passed away in 1937. He did a last turn as Lee Chan in 1938 film Mr. Moto’s Gamble in 1938, with Peter Lorre playing Mr. Moto. Luke returned to the role again in 1948 and 1949, with the reboot of the Charlie Chan franchise, despite the fact that Roland Winters, playing his father, was younger than him. Finally, in 1972, Luke got to play Charlie Chan himself, albeit as a voice actor, in the short-lived Hanna-Barbera children’s show The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan, with a cast that included, among others, Jodie Foster.

In 1941 Luke found a second round of success, again as a sidekick, this time as Kato in the 1940 film serials The Green Hornet and The Green Hornet Strikes Again. Luke was heavily featured in almost every episode, as he would don a pair of motorist’s goggles and a cool hat and fight crimes alongside The Green Hornet, a sort of proto-Robin to the Hornet’s Batman (Robin made his comic series debut just a few months after The Green Hornet had premiered). The character of Kato was later played by Bruce Lee in his first US production, the TV remake of The Green Hornet (1966-1967), and Keye Luke appeared in a guest spot in the series.

Friends of martial arts movies, on the other hand, are probably going to recognise Keye Luke as the blind Master Po in the 1972-1975 TV series Kung Fu, starring David Carradine, as well as its movie remake Kung Fu: The Movie (1986). Younger audiences remember him as the old Mr. Wing who gives Billy the Mogwai in Gremlins (1984) — Luke reprised the role in Gremlins 2 (1990). He also appeared in a number of other science fiction movies, including Project X (1968) and Dead Heat (1988), as well as a slew of SF TV series, many of them animated. Additionally, he provided some dubbing for at least two Godzilla movies.

Before I finish this article, I’d like to take the opportunity to write a few words about author Maurice Renard. I have written about him at length in my review of The Hands of Orlac, so head over there if you want to know more. However, in short one could say that Maurice Renard represented to French readers what Hugo Gernsback did to American readers, as a populariser of the idea of science fiction as a distinct genre — with the exception that Renard was a decidedly better author. Maurice Renard’s groundbreaking work in French sci-fi has only started to become recognised in the Anglophone world in the last decade, mainly thanks to a heroic translation effort by Brian Stableford, who released five new translations of his works in 2010. Prior to that, Les Mains d’Orlac was the only one of his novels that had received a proper translation, and thus it remains his best known work outside of France.

Renard is generally considered the foremost sci-fi author during France’s Golden Age of speculative fiction (1880-1940). Like his American counterpart, Renard wrote several serious pieces trying to outline what he saw as a completely new genre in literary fiction. Gernsback tried to make the term “scientifiction” stick, probably for the first time around 1916, although he later also introduced the term “science fiction”, but bever quite liked it. Maurice Renard called the genre “le merveilleux scientifique” or “the marvellous scientific”, and its literary product “le roman merveilleux-scientifique” or “the scientific-marvellous novel”. His first use of the term was probably in 1909, seven years before Gernsback’s “scientifiction”. Both Renard and Gernsback were acutely aware of the fact that writers of the late 19th and early 20th century had been in the process of forging a wholly new literary genre distinct from other forms of speculative or fantastic fiction. Both also felt that some of the vague terms used to describe these works, such as “science romance” or “anticipation novel” were misnomers.

Renard not only speculated theoretically, but wrote volumes of sci-fi himself, even if much of his work is an eclectic mix of genres, ranging from detective stories to pure SF to gothic horror to satirical comedy, to fantasy and adventure and even romantic novels. His most lasting legacy to SF mainstream is probably that of the transplant and body part subgenre. Much of the transplant and stitched-together-bodyparts books and films made past 1908 can draw its lineage from Maurice Renard. All the brain switcheroo pulps and films so popular from the thirties to the sixties came from Renard’s earlier novel Doctor Lerne, the original transplant novel, published in 1908, in which he introduced the cyborg, the the human transplant, the animal-human hybrid, etc. This book, along with The Hands of Orlac, were translated into English, but both were badly hacked up by American publishers, removing many of the risqué elements, making them go rather unnoticed past English-language readers. More importantly, though, most of Renard’s major novels were quickly translated into German and Hungarian, and given the importance of German and Hungarian filmmakers and producers for the emergence of Hollywood horror and science fiction films, he was probably a much better known author behind the scenes in Tinseltown than to the general public. Hugo Gernsback himself, the Luxembourgian emigré, would most certainly have been aware of his writings.

The theme which Renard may most universally lay claim to is the transplant theme, one which he returned to in The Hands of Orlac in 1920, and several other times. Not only has The Hands of Orlac been adapted for the screen several times, but the theme of the “haunted body part” is one that has been subsequently used in numerous fantasy, horror, sci-fi and adventure films. Pretty much every time you see a severed hand crawling across the floor, it’s a nod to Maurice Renard.

Janne Wass

Mad Love. 1935, USA. Directed by Karl Freund. Written by Guy Endore, John L. Balderston, P.J. Wolfson, Leon Gordon, Edgar Allan Woolf, Gladys von Ettinghausen, Leon Wolfson. Based on novel by Maurice Renard. Starring: Peter Lorre, Frances Drake, Colin Clive, Ted Healey, Sara Haden, Edward Brophy, Henry Kolker, Beye Luke, Nay Beatty, Ian Wolfe. Music: Dimitri Tiomkin. Cinematography: Gregg Toland, Chester A. Lyons. Editing: Hugh Wynn. Art direction: Cedric Gibbons. Makeup: Norbert A. Myles. Sound: Douglas Shearer. Dialogue director: John Langan. Produced by John W. Considine Jr for MGM.

Leave a comment