(10/10) Paramount’s 1932 adaptation of H.G. Wells’ novella The Island of Dr. Moreau is the best of all the legendary 1930s sci-fi/horror movies. The daring script touches upon highly controversial subjects, Karl Struss’ fantastic cinematography and lighting create a feverish tropical nightmare, Charles Laughton and Bela Lugosi are mesmerising in their roles and Charles Gemora’s makeup is some of the best ever created.

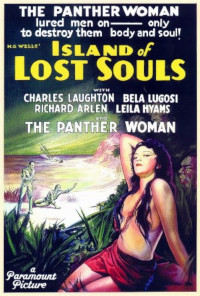

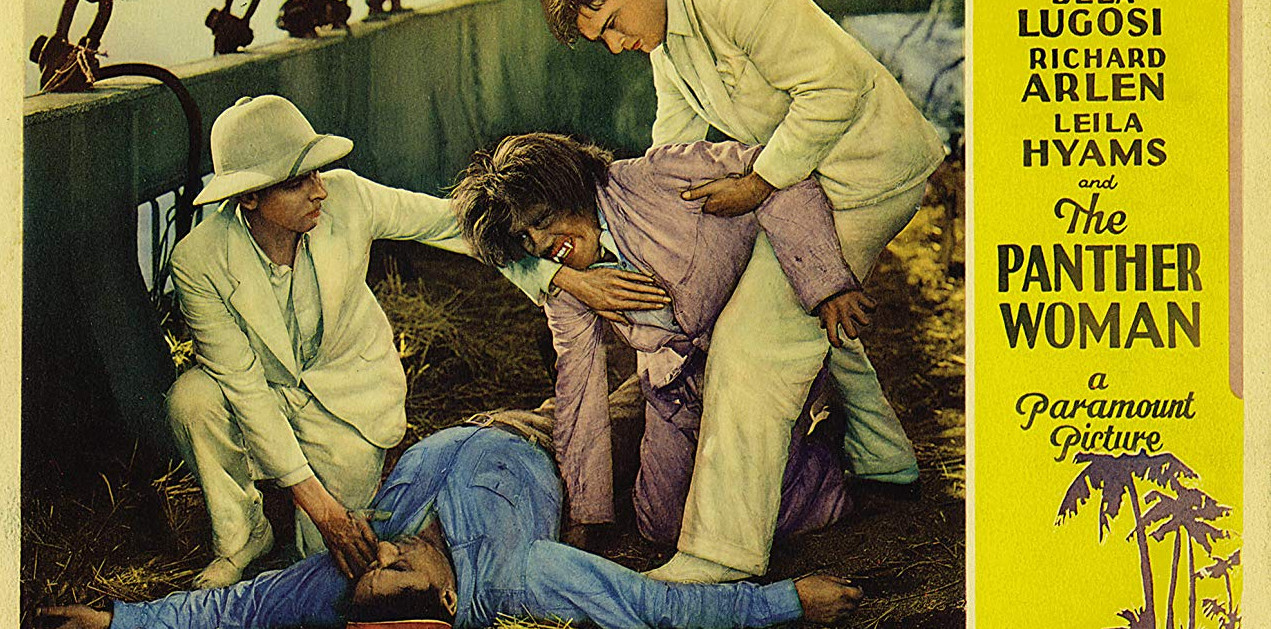

Island of Lost Souls. 1932, USA. Directed by Erle C. Kenton. Written by Philip Wylie & Waldemar Young. Based on the novel The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells. Starring: Charles Laughton, Richard Arlen, Bela Lugosi, Kathleen Burke. Cinematography: Karl Struss. Make-up: Charles Gemora, Wally Westmore. Produced for Paramount. IMDb score: 7.6. Tomatometer: 96. Metascore: N/A.

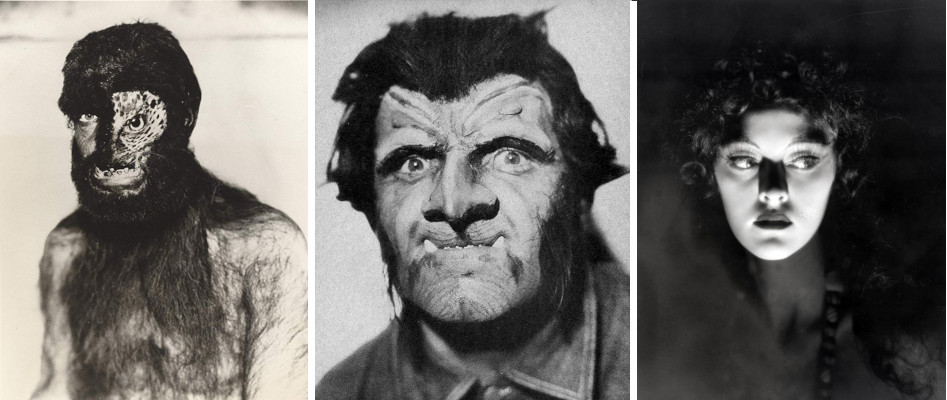

”Not to walk on all fours! That is the law! Are we not men?” chants Bela Lugosi in heavy manimal make-up in as scene from the 1932 film Island of Lost Souls, that has since become a classic. Although it is often clumped together with the Universal horror pictures of the time, like Frankenstein (review) and Dracula (both 1931), it was in fact made by Paramount, who also made Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931, review). In both these Paramount horrors, you can see a sort of refinement and style that was lacking from the Universal pictures, Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review) perhaps being the exception.

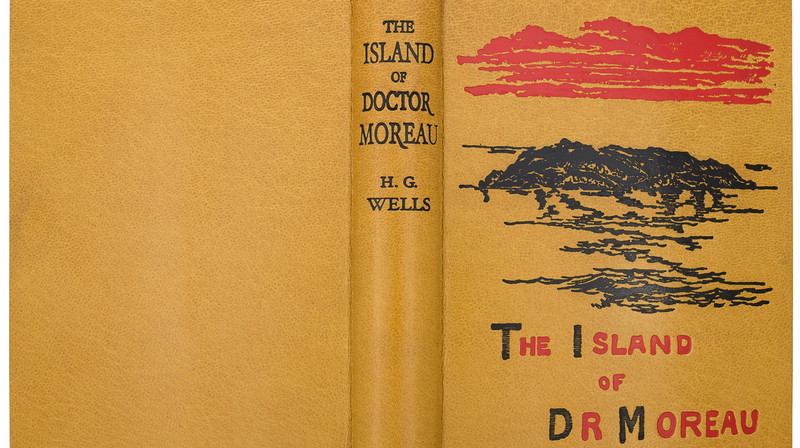

Island of Lost Souls is based on the novella The Island of Dr. Moreau, written by the father of modern science fiction, H.G. Wells, in 1896. It was Wells’ third novel, after The Time Machine and The Wonderful Visit (both 1895).

The Island of Dr. Moreau starts with Briton Edward Prendick (whose last name seems to have been changed in every film adaptation, for some reason) and two other men shipwrecked in a dingy. Prendick is the narrator, and in a short, but important, prologue he recounts the horrible experience of being eight days adrift without water. Finally the marooned mates decide to toss coins – the one who loses, it is implied, will be killed and used for drinks (Wells is here clearly inspired by a similar situation in Edgar Allan Poe’s novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket). Prendick initially would rather sink the boat, and guards himself with a knife, but later succumbs to the ghastly compromise. The coin toss leads to a struggle between the other men, who fall overboard and drown – at which Prendick laughs, and adds that he now feels ashamed of his reaction. This chapter is short and seems like a throwaway prologue, and I have an inkling that it bore greater significance at some point – perhaps making Prendick kill one of his fellow passengers, but that either Wells himself or the publisher might have not wanted to lay that baggage on the protagonist. However, the scene illustrates one of the major themes of the book – the will to survive, the eternal struggle for survival, be it of the individual, or of life itself.

Prendick gets picked up by a boat and is left on an uncharted island, inhabited by a Mr. Montgomery, and his boss, the once brilliant doctor and scientist Moreau – and his strange looking servants. Moreau treats Prendick pleasantly and hospitably, but at night he is locked into his room and hears strange noises. In the morning he hears screams from another room, and is shocked to find the doctor performing a horrible vivisection without anaesthetics on what looks to be a human being. He concludes that he himself must be the intended next victim and tries to flee, but is in turn faced by ”the natives” – horrible man-beasts that he surmises must once have been men, but are now deformed by the actions of Moreau. One of them is the Sayer of the Law, who recognises Prendick as a being with five fingers as himself. He then teaches Prendick the laws of humanity, including not to walk on four legs, not to lap one’s drink, not to eat meat and not to kill other beings. Moreau catched up with Prendick at the shoreline, and convinces him that he means him no harm by handing him his gun.

Later Moreau explains that Prendick has misunderstood – the creatures he has seen have actually been animals to begin with. Moreau says that he was smoked out of the scientific community for his experiments and theories, and found this island to conduct them on. According to Moreau, the human being is the pinnacle of evolution, and all living things strive toward the human form. Therefore, what he has done through the use of surgery, has simply been to speed up evolution in order to not only perfect the animals, but the human being as well – to create a perfect race of humans. But it all goes awry as one beast, the Leopard Man, is caught killing a rabbit – forbidden by the Law of the island, as a measure of security so the manimals won’t turn into flesh eating beasts. The humans hunt down the Leopard Man, and the chase ends up with Prendick killing it to spare it further pain in the House of Pain (which is the universal punishment). But this is a bad idea, since the manimals have now seen one of the men break the Law by killing another creature, thus rendering the Law meaningless. The situation further escalates when a puma that Moreau works on breaks free – Moreau chases it down, and they end up killing each other, which leads to Montgomery breaking down, leaving the manimals leaderless. He also destroys all boats on the island, and is later killed.

Prendick – marooned and alone – learns to live in some kind of harmony with the manimals – becoming sort of a substitute Moreau, but they start regressing to their animal ways, and Prendick is forced to shoot one of them as it attacks him. By chance he happens on a boat, and is later picked up by a ship. Back home, he describes how he is unable to readjust to society, as he no longer sees his fellow men as humans, but rather as animals, just inches away from retorting back to their primitive ways. Thus, as Wells began his book by borrowing from Poe, he ends it by borrowing from Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.

First and foremost The Island of Dr. Moreau is a protest against the vivisection of animals in the name of science and commerce. In the late 19th century there was a growing movement of resistance to animal cruelty, and Wells put himself as one of its spearheads with his book, which was written as a pamphlet. But the novella also deals with a number of more philosophical questions, including such as social darwinism and the moral limits of science. At the end of the 19th century – although we were still 40 years away from Doktor Mengele and his cruel human experiments – eugenics was a hot topic. Inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, some scientists in the late 19th century started recommending sterilisation of certain mental patients, and promoting the idea of refining the human race. In Britain Wells would also be aware of the way none-whites were still considered by large parts of society as inferior beings, almost half animals. Wells himself was fiercely anti-racist and opposed colonialism. The way in which he portrays the ”natives” of Moreau’s island clearly mirrors the way many colonialists viewed the original inhabitants of the colonies. Literature of the age was also filled with this image. Even authors who were basically sympathetic of these other cultures still painted an image of non-westerners as primitive and dumb. And of course the way Moreau and Montgomery run the island, subjugating the manimals, is also a commentary on both colonial policies and on slavery – as well as on the class society, the main theme of Wells’earlier book The Time Machine, and one to to which he would constantly return.

Lastly, there is the philosophical question of what ”man” really is – naturally another hot topic for debate after the publication of Darwin’s theories on evolution some decades earlier. Is the human simply a refined animal, or is she even refined at all? Does she simply wear a thin coat of civilisation to hide her real animal self? Is man really a more moral being than her animal counterpart? The answer is clear on the point of Moreau, but is Prendick – really – any better himself, or is he simply trying to cover up his real self?

The ending of the book, with Prendick seeing his fellow humans as animals on the brink of regressing, clearly mirrors another book that deals with the notion of the “superior white man” – Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Gulliver’s last journey is taken to the land of the Houyhnhnms – intelligent horses, supremely more noble and moral than most men. The savages of this land are the filthy, brutal Yahoos, a sort of man-ape, and Gulliver is first mistaken as a Yahoo and treated with disgust by the Houyhnhnms. As Gulliver returns home, he is no longer able to stand the sight and smell even of his family, as they are in his eyes now merely lowly Yahoos in contrast to the noble Houyhnhnms.

H.G. Wells hated the movie – which is not too surprising, since he hated most of the movies based on his works – with the exception of James Whale’s The Invisible Man (1933, review), for which he demanded script approval, and, one can presume, the 1936 film Things to Come (review) , for which he wrote the screenplay himself. In Wells’ opinion Island of Lost Souls put to much emphasis on the horror elements instead of the philosophical ones. He may have had a point, but was in my humble opinion quite too harsh on the filmmakers. Indeed, the book just screamed out to be made into a horror film – and it is without doubt one of the most thoughtful horror flicks of the era. It is also one of the few that are still very creepy today – as compared to a Dracula or a Wolf Man. And in fact, if you dig a bit deeper below the frights, the film still retains most of Wells’ philosophical ponderings, and indeed even adds a few of its own – such as the story concerning the Panther Woman, which we will get to later. But Wells was never one for subtlety, as vividly demonstrated by the propagandist moral soufflé that is Things to Come. Indeed, I would say that from a dramatic point of view, most of the changes to story made by the screenwriters are actually improvements on Wells’ book, even if I’m aware that this statement will rub some people the wrong way.

Although often called the first film adaptation of The Island of Dr. Moreau – the film in fact isn’t. The very first (known) adaptation is an 1911 French silent film called L’ile d’épouvante, more known in the States as The Island of Terror, as it was released in 1913. L’ile d’épouvante was a loose reworking of The Island of Dr. Moreau and the novel Le Docteur Lerne – Sous-Dieu (1908) – literally Doctor Lerne – Demigod — written by the criminally neglected French sci-fi pioneer Maurice Renard. It was translated into English as New Bodies for Old in 1923, and had an overhaul in 2010 by Brian Stableford as Doctor Lerne. The book itself seems loosely based on The Island of Dr. Moreau, and author Renard even included a dedication to Wells. Although not as famous as his idol, Renard also made quite an impact on sci-fi and horror films with a few of his better known novels – most famously Les Mains d’Orlac (The Hands of Orlac, 1921), which has been turned into four big screen films and one French TV adaptation.

Renard was to France what Hugo Gernsback was to the US. Renard was a champion of the notion of regarding science fiction as a separate genre, at a time when it was regularly clumped together with other pulp fiction, like penny dreadfuls, detective stories and adventure stories. While Gernsback is credited for coining the term, “science fiction” in 1926, Renard had basically coined it in French fifteen years earlier, although a direct translation would be “marvellous-scientific”. Despite his great contribution to the genre, he was all but unknown in the Anglophone world up until 2010, when the great Brian Stableford released his five main novels in new English translations. Even if few can name any of his works, his influence has spread into science fiction through osmosis. His biggest contribution is probably in the body horror subgenre of transplant fiction and bodyparts with a will of their own, a theme that he showed a downright unhealthy fascination with. But I digress. This is a film review.

As noted earlier, the film follows the book in broad terms. The screenwriters were not just any hacks. Waldemar Young had previously worked on Tod Brownings’s London After Midnight (1927) and would go on to write for Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932) and Cleopatra (1934). Philip Wylie was a noted author whose 1930 novel The Gladiator was one of the main inspirations for the Superman comic. In 1933 he wrote When Worlds Collide, made into film by George Pal in 1951 (review). He wrote a number of science fiction novels discussing societal issues and issues of gender and sexuality, and was both heralded as a feminist forerunner and, interestingly, a misogynist, which has been vehemently denied by his daughter. Wylie also worked on another Wells adaptation in 1933 – The Invisible Man.

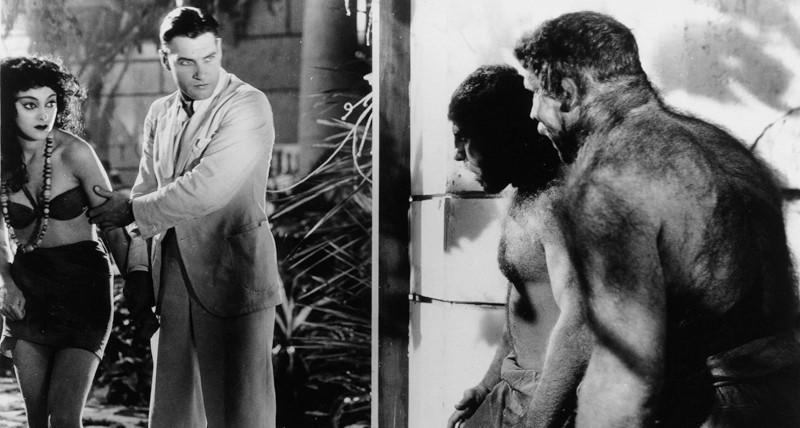

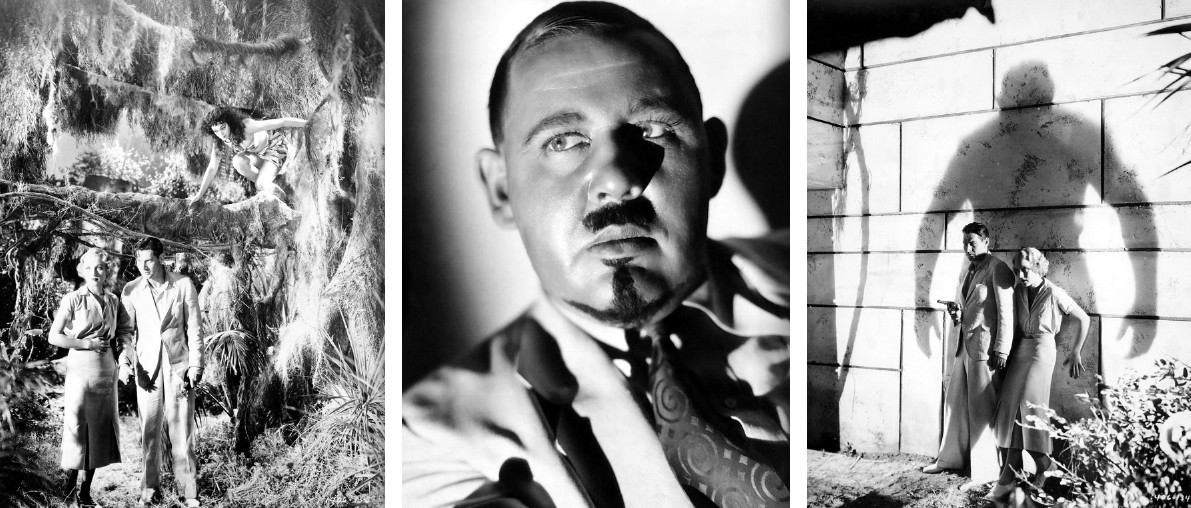

Prendick – now renamed Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is shipwrecked and picked up by a boat carrying animals, and is taken to Moreau’s island where he is first well received until he finds out that Doctor Moreau (Charles Laughton) is performing horrendous vivisection in ”The House of Pain”. When trying to leave he is confronted by the manimals, led by The Sayer of the Law (Bela Lugosi), who are frightened into submission by Moreau who threatens them with The House of Pain unless the Law is upheld.

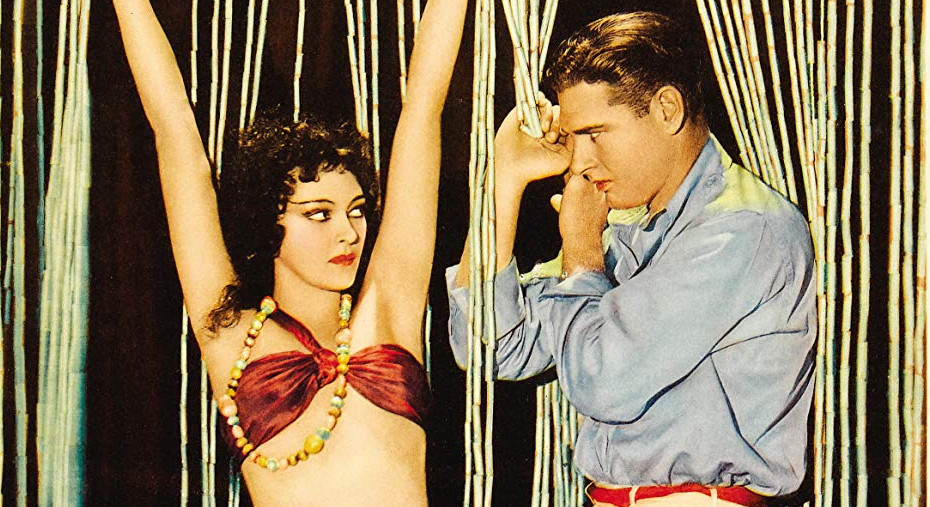

There are, however a few additions, most notably the Panther Woman Lota (Kathleen Burke, initially uncredited). Lota is introduced to Parker as a sort of an adopted daughter of Moreau’s, and when Parker remarks that she doesn’t look like the other ”natives” she replies that Moreau ”brought her” to the island. Moreau encourages her to spend time with Parker, and, unsurprisingly, they fall in love. Now, this may at first glance just seem like a Hollywood ploy to stick a scantily clad native girl into the film, and it partly is. The Panther Woman isn’t even referred to as ”the Panther Woman” in the film, but the name was featured heavily in its marketing strategy – even with false advertising such as ”The Panther Woman lured men on – only to destroy them body and soul” written on the posters, which has nothing at all to do with the actual plot. It is later revealed, of course, that the woman was originally a panther – Parker notices this as he is making out with her, and gets stung by her claws that have begun to grow out again. When he confronts Moreau in anger, the doctor explains that Lota is his most perfect creation, and he had hoped to see if a manimal could fall in love with a human being. At first he is enraged as he thinks his experiment has failed, but seeing her devastation at her own ”ugliness” which prevents her from having Parker, he realises that he has indeed succeeded in making a woman out of her — now he only has to take her back to the House of pain, to ”burn out all the animal” in her. This is a thoroughly creepy scene with Charles Laughton doing a splendid job – and it isn’t made less discomforting by Moreau first patting her with a combination of lust and fatherly love, and then orders another of the manimals to rape her, as Parker won’t make her pregnant.

The addition of the Panther Woman must have been extremely difficult to bear for some studio executives, and would never have passed the Hays Code, enforced only two years later. It actually brought in even heavier philosophical material than Wells himself dared to poke at with a stick – such as love between man and beast, sex slavery, rape and the notion of an incestual relationship between Moreau and Lota. It is also interesting to see that Parker doesn’t seem to mind much that Lota is actually not human – as he is ardent about taking her with him as he escapes. John Stapledon would cause outrage 12 years later with his novel Sirius about a woman and her (presumably platonic) love relationship with a super-intelligent dog. These are issues that are of course still highly sensitive.

Another addition is Ruth Thomas (Leila Hyams), Parker’s girlfriend, who is waiting for him at a harbour town when he is shipwrecked. Moreau’s assistant Mr. Montgomery (Arthur Hohl) – believing that he will continue with the ship to land, radios in a message from Parker to Ruth from the ship. As Parker isn’t on board when the ship arrives, Ruth confronts the captain who dumped him on the island (Stanley Fields), after a fight, and he reveals the coordinates of Moreau’s secret hideout. Instead of playing the damsel in distress, Ruth arranges for a rescue party to go and bail out her hubby in distress. The screenwriters (presumably Wylie first and foremost) also don’t have her screaming and fainting at the sight of the deformed inhabitants serving as waiters and manservants, rather she seems to keep her calm a lot better than her boyfriend. The character doesn’t really bring anything essential to the plot, but as a composed woman of action she is a very welcome addition to a genre prone to portraying women as fainting, tripping scream queens. (I mean seriously – why do women always trip over their own feet in these movies?)

The third major change is having Moreau die at the hands of the manimals taking their revenge, rather than being killed while heroically fighting a puma. In one of the film’s most disturbing scenes we see a throng of man-beasts dragging Moreau to the House of Pain, they start picking up scalpels and surgical tools, and we hear Moreau screaming in pain off-screen. Indeed, from a dramatic point of view, this, as well as other additions and changes are, in my opinion, improvements on the novella.

The film could still have sunk into obscurity, had the role of Dr. Moreau been played by a Lugosi or a Karloff. Instead Paramount scored a jackpot when they got British Shakespearian actor Charles Laughton. The great Laughton brings a mad talent to the role of Dr. Moreau, fully equipped in a crumpled, plantage owner’s white suite, a whip and a gun at his side, portraying the stern but ”just” father figure of the manimals. In fact, he is the god of his own little kingdom that he has created for himself. His Moreau has a British refinement and elegance, juxtaposed by the brutalities he exercises. But despite his cordial and generous manners, there is from the beginning, even before his atrocities are revealed, a sense of smug self-satisfaction and haughtiness about him, and when explaining his experiments to Parker, he is desperate to show off, boastingly asking if Parker knows ”how it feels to be God” (a remark that the sceptic Wells hated). The total command of the manimals, and the assuredness that nothing can harm him, is rendered all the more tragic when his creations finally exhort their revenge. Laughton brings a class to the acting that few, if any, other early horror/sci-fi films had.

Laughton also brings a much needed lightness to the film, cracking little sadistic jokes and knowing one-liners, and finding the whole situation thoroughly amusing. He underplays, rather than overplays, Moreau, adding a touch of a pampered upper-class bully, making the doctor out as a rotund, deviant devil. But what is worth noting is that the rest of the film is completely devoid of humour. Indeed there is no Una O’Connor running around like a headless chicken, screaming the ears off everyone in the audience.

The other scene stealer of the film is Bela Lugosi, as the tortured and haunted Sayer of he Law. Under his heavy make-up one can glimpse the genius of a Lugosi in top form, not restrained by the laughable scripts and roles he was offered later in his career. He has very little screen time, but is often the best remembered actor of the film. The scene where Moreau confronts the manimals when they are about to attack Parker is pure film legend.

Dr. Moreau: What is the law?

Sayer of the Law: Not to eat meat, that is the law. Are we not men?

Beasts (in unison): Are we not men?

Dr. Moreau: What is the law?

Sayer of the Law: Not to go on all fours, that is the law. Are we not men?

Beasts (in unison): Are we not men?

Dr. Moreau: What is the law?

Sayer of the Law: Not to spill blood, that is the law. Are we not men?

Beasts (in unison): Are we not men?

All the more potent then, is the scene before the whole thing explodes, when the manimals confront Moreau, and he asks them if they have forgotten about the House of Pain, and the Sayer of the Law replies: ”You! You made us in the House of Pain! You made us … Things! Not men! Not beasts! Part man … part beast! Things! Things!”

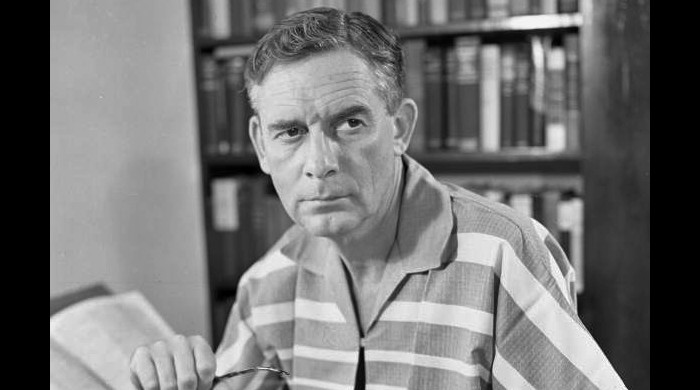

All in all, the film is very well acted across the whole board. Richard Arlen is not a very famous actor, but got his claim to fame in 1927 in the silent Academy Award winner Wings, playing a daring pilot. Back in the silent days, when a square jaw was sometimes more important for the romantic lead than being a good actor, he looked as if slated for fame, but for some reason he was never able to transcend into A-list films, Island of Lost Souls being one of the few exceptions. He is often lambasted for being non-descript in this film, ”wet noodle” is a phrase I’ve seen used – which simply isn’t fair. Of course he is outshone by Laughton and Lugosi, but that is partly because of his role – there is only so much you can do as the moral, goody-two-shoes leading man in a picture filled with sadistic mad doctors and beast men. As a matter of fact, Arlen brings a good deal of humanity and emotion to the role – and he does what a good actor does: he makes his co-actors look good. He listens, and he reacts. And it’s these reactions to the horrors that go on around him – naturalistic, real reactions, rather that overplayed, that makes the sadism of Laughton or the ugliness of the creatures all the more horrifying. Arlen also appeared in the deplorable Z-film The Human Duplicators from 1965, starring Richard ”Jaws” Kiel. However, before that he showed up in the 1944 mad scientist film The Lady and the Monster (review), in the lead, no less.

Arthur Hohl as the self-loathing Montgomery is absolutely brilliant, as is Stanley Fields as the captain of the ship that brings Ruth to the island and becomes the third “captive” of Dr. Moreau. Leila Hyams, as said before, plays a composed, strong female character. Even Kathleen Burke as the Panther Woman does a great job of fleshing out a role that might have just been played for the exploitation value.

Director Erle C. Kenton had a long career that spanned both silent films, talkies and TV-series. Curiously enough, Island of Lost Souls towers supremely as his most accomplished picture. Much of his film work included light comedies (he did two with Abbot and Costello), dreary melodrama and Z-grade westerns and thrillers. Toward the end of his film career he directed some of the regrettable swansongs of the Universal horror franchise, like The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942, review), The House of Frankenstein (1944, review) and The House of Dracula (1945, review). Soon after that he moved into television, where he remained for the rest of his career.

Thus it is a bit surprising that this film looks as good as it does. The film is very dark and claustrophobic, you can almost feel the tropical heat and the jungle closing in about you, as the madness closes in about the main characters. Most of the film takes place in and around Moreau’s walled-in estate, a white-limed complex with a maze-like feel, part colonial mansion, part dungeon, surrounded by a bizarre garden of huge, genetically enhanced plants, a strangely romantic pond and — seen through the window s– medieval treadmills run by strange-looking slaves: Moreau’s “failed experiments”. The mis-en-scene and details are all just so, from the tropical wicker furniture to the ornamented, oriental-styled tea pots, heavy silver trays and Victorian china, which combined with the white suits worn by Moreau and Montgomery further enhance the idea of Moreau as the sadistic colonial overlord of his own private universe — in essence a sort of Colonel Kurtz. Indeed, there is a clear kinship between Wells’ novella, and the feverish anti-colonialist classic Heart of Darkness, written by Joseph Conrad only three years after the publication of The Island of Dr. Moreau. And I daresay that while Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now (1979) is based on Heart of Darkness, Coppola, as a fan of horror films and a part of the famous California film school generation of directors, was most certainly inspired by Island of Lost Souls in creating the claustrophobic, hallucinatory atmosphere for his film.

Kenton uses suggestive and odd camera angles, beautifully framed shots and and innovative pans and zooms. The most effective scene of the film is probably when the manimals, released from their spell and obligation to Moreau revolt. While a crowd of deformed creatures bearing torches chant in the background, Bela Lugosi delivers his spine-chilling speech on how they are “Not men! Not beasts! Half-men! Half-beasts! Things! Things! At the end of his speech, he suddenly steps forward, filling the whole frame with his wild, made-up face, shouting straight at the viewer, as if accusing the audience: “Things!” The camera then cuts to another bizarre creature, who in turn steps forward, right up to the audience, shouting “Half-men!”. Cut to the next creature: “Half-beasts!”. And this keeps going, as a frenzied mass of half-intelligent man-beasts, suddenly awakened from their slave-like existence under the torture of Moreau, start marching on their master, but really they march on the audience, through the almost pitch-black set with their torches ablaze. This is a clever reversal of the Frankenstein movie, where the townsfolk marched with their torches on the — essentially innocent — Creature. Now, the creatures march on their maker.

While Kenton was a reliable and professional director, none of his other work show the passion, style or inventiveness that this movie does. In an interview monster movie super fan Bob Burns suggested that Kenton was “still a young man” and not jaded by the business, but this doesn’t hold water: By 1932 Kenton had directed close to a hundred films.

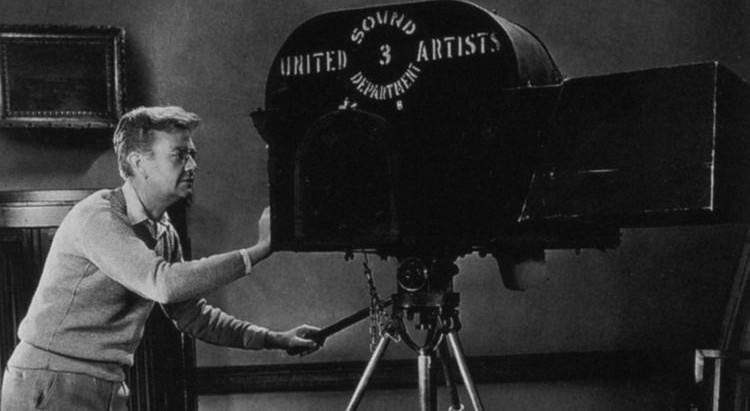

The main reason for the film’s quality is probably the director of photography, Karl Struss. New Yorker Struss worked with greats such as F.W. Murnau, Cecil B. DeMille, Charles Chaplin and D.W. Griffith. He was awarded with the first ever Oscar for cinematography for Murnau’s Sunrise (1927), and was nominated three more times. He filmed Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross and Robert Florey’s Hollywood Boulevard, as well as the early colour film Aloma of the South Seas (1942). But he also moved about genre cinema. In 1931 he, alongside director Florey, proved that sound didn’t have to mean static shots with the praised version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, starring Fredric March. He also filmed Rocketship X-M in 1950 (review), the alien computer film Kronos (review) in 1957 and the sci-fi classic The Fly in 1958. Known as one of the great innovators of Hollywood cinematography, one wonders how much of the film wasn’t actually directed by Struss, rather than Kenton.

The wonderful look and design of the film is created by German-born Hans Dreier, one of the great art directors of Golden Era Hollywood. Between 1938 and 1947 he was nominated for an Oscar every single year: he was nominated for an award an astounding 17 times, and won three Academy Awards. During his career Dreier oversaw the art direction for over 550 films, much of it as supervising art director for Paramount.

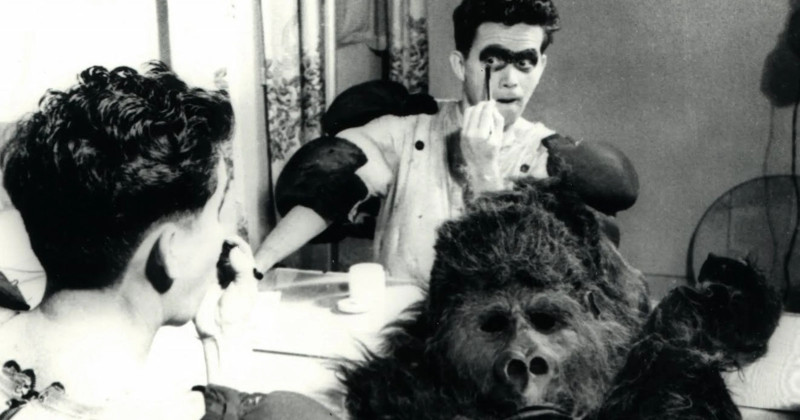

One of the most prominent features of the film is the amazing make-up for the manimals, making them look really frightening with snoots, hoofs and fur all over – but still retaining much of their human features. The casting agent also used a lot of actors with unusual or deformed faces, adding to the creepiness. Working on the make-up for the manimals were Charles Gemora and Wally Westmore. Filipino émigré Gemora started out in Hollywood as a sculptor, working on many silent films for Universal, such as Phantom of the Opera and Noah’s Ark, before using his talents to design gorilla suits for films. He realised that his short stature made him perfect for playing gorillas, so he donned the suits – and others that he created for a number of films. He played gorillas in dozens of films, becoming universally known as The Gorilla Man. He appeared as a gorilla in high profile films such as Gunga Din, Around the World in Eighty Days and The Ten Commandments. He also created the memorable alien of the 1953 film War of the Worlds (another Wells adaptation, review). He can be seen as a caged gorilla in he beginning of Island of Lost Souls, but was presumably too busy doing make-up to appear in the rest of the film. Wally Westmore, of course, was one of the famed Westmore brothers who dominated make-up scene of Hollywood from the thirties to the sixties, landing spots as heads of makeup of nearly all major studios.

Gemora was virtually unknown to anyone but the insiders of the movie industry during most of his career — but this small-statured and generous jack of all trades was nothing short of a genius. Athletic, driven, artistic and extremely talented in so many ways, Gemora worked on hundreds of movies, almost universally without getting any screen credit. After arriving in Hollywood as a stow-away on a sail ship he used his artistic talents to draw speed portraits of people outside Universal studios, and was soon invited in to start doing work at the studio’s sculpture department, and later the makeup department, where it was that he was tasked to create his first gorilla suit. Realising that with his small stature, he was ideal to play the ape himself, he launched on his now legendary career as the original ape man. His mechanically enhanced ape suits were considered the best in the business and served as the blueprint for many later suit effects. It was while working with ape suits that Gemora also carved a niche for himself as a specialist in hair work, which is on full display in Island of Lost Souls. The sheer number of manimals in the picture means that there must have been a small army of makeup people working on the film, and much of the makeup of the extras in the background was probably just simple pull-on masks, but there are at least a dozen beasts with very elaborate prosthetic makeup and hair work, which must have kept Gemora extremely busy. As a little side-note: many of the extras called in to play manimals had no idea of what kind of picture they were making, they were simply people on a call-sheet who were called in to do another day’s work, and must have been rather astonished when presented with their suits and makeups.

Charles Laughton made his bones as a praised stage actor in London, and started appearing in short films starring his future wife Elsa Lanchester in 1928. One of them was especially written by H.G. Wells himself. Lanchester, of course, would later go on to horror sci-fi fame as the title character in the 1935 film Bride of Frankenstein. In the thirties Laughton andLanchester made the move to Hollywood, although they continued to appear in British films. Laughton quickly shot to fame as one of the greatest actors of Hollywood, and despite not looking like a traditional leading man, went on to play the lead in a number of high profile films, many of which won Oscars. Laughton himself won an Oscar, and was nominated for two more. He is perhaps best known for the title role in The Secret Life of Henry VIII, (1933), directed by the great Alexander Korda – the film became his calling card for great roles (and it gave him his Oscar), and as Captain Bligh in Frank Lloyd’s Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), for which he was nominated for an Oscar and won the New York Film Critics Circle Award. He played Rembrandt van Rijn in Korda’s 1936 film Rembrandt, starred in Hitchcock’s last British film Jamaica Inn (1939) and played Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame the same year.

In the forties Laughton made films for Hitchcock, Lewis Milestone, Jean Renoir and Irving Allen. In 1953 he played King Herod in William Dieterle’s epic Salome, and was nominated for an Oscar, a Bafta and a Golden Globe for his work in Billy Wilder’s 1957 film Witness for the Prosecution. He was again nominated for a Bafta for his last film, Otto Preminger’s Advice and Consent (1962). The three-time Academy Award winner and legendary method actor Daniel Day-Lewis has said that Charles Laughton is his greatest inspiration as an actor. Laughton and Lanchester were married throughout their lives, although in her autobiographical book, Lanchester confirmed what had long been rumoured, that Laughton was in fact gay, and the marriage, although not necessarily an unhappy one, was partly help together to make Laughton “acceptable” in the homophobic film industry of Hollywood and London.

Leila Hyams had a short film career spanning merely 12 years from 1924 to 1936, but was well received by audiences and critics alike. Her background was as a vaudeville performer with her parents and a model. She quickly shot to fame as a capable female leading star in dramas, but is perhaps best known for her two horror roles, both in 1932 – as the wisecracking, but sweet circus performer in Tod Browning’s Freaks, and Island of Lost Souls. Hyams was considered for the role as Jane in the 1932 film Tarzan the Ape Man, but the role went to Maureen O’Sullivan – seen in 1930 in the sci-fi musical comedy Just Imagine (review). She retired of her own will in 1936.

Even shorter was the film career of Kathleen Burke. 21-year old Burke was a dentist’s assistant who had some modelling and acting experience from radio and stage when she submitted her photo to a competition looking for the actress to play the Panther Woman. She was reportedly “chosen out of over 60 000 contestants”. But the role meant she was typecast as the exotic temptress, often relegated to play ”the other woman”. Despite appearing in a few A-list films with actors like Cary Grant and Gary Cooper, she decided to call it quits just six years later, in 1938, seeing that her career wasn’t progressing.

Arthur Hohl (Montgomery) was a noted stage actor who also played small roles in a number of films, often as a villain. Hohl’s two performances seen most often today are the nasty boat engineer in the 1936 film version of Show Boat, and the one in Island of Lost Souls. He teamed up with Laughton again in Cleopatra, The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Sign of the Cross, and appeared in Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947).

One of the manimals, M’Ling, Moreau’s loyal servant, is played by Japanese-born actor Tetsu Komai, who played a number of small parts, mostly villainous characters, for many decades in Hollywood. He had small roles in two sci-fi serials: Adventures of Captain Marvel in 1941 and Captain Midnight in 1954. The future Flash Gordon (1936, review), Buster Crabbe, and fifties movie great Alan Ladd are said to have appeared as beast men, but this is unconfirmed.

Bela Lugosi, of course, requires no further introduction. Here he was a year and a half past his star-making turn as Dracula (1931), which had launched a string of successes, like The Black Camel (1931), Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) White Zombie (1932) and Chandu the Magician (1932, review). Here he was still able to pick and choose roles, as he hadn’t yet squandered his earnings from films that he was still making decent paychecks from. Much has been written and speculated about the fact that Lugosi didn’t play the Frankenstein monster that he was originally slated to display. His official explanation was that he didn’t want to act with makeup covering his face, and thus turned down the role. But very little of what Lugosi stated about himself during his Hollywood career was the full truth, and there are other circumstances that point to the fact that Lugosi was rather kicked off the film when James Whale replaced the original director. That Lugosi is seen in Island of Lost Souls completely covered in makeup is another pointer to the theory that makeup wasn’t as big a problem for Lugosi as he liked to make out (although it is documented that he was no fan of long makeup sessions). Whatever the case, Bela Lugosi was in the absolute prime of his career in 1932, both artistically and commercially. His role as Sayer of the Law is simply mesmerising, and without doubt counts among his top five performances.

Island of Lost Souls was not as successful as the previous horror films made in 1931, for reasons perhaps best left to others to speculate about. I have a hard time seeing why – perhaps it didn’t have the iconic monster of Frankenstein, Dracula and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde – and The Invisible Man released in 1933. Or perhaps the audience simply saw it as too horrific. Neither did it get the same sort of rehabilitation as many of the other early horror pictures when the DVD format was introduced. For example even Universal’s and Hammer’s Z-grade films got lavish re-releases long before Island of Lost Souls. It has, however, gained some recognition during the last few years as Universal has bought its rights, and included it in its horror franchise. Nevertheless, it was far from a flop when it was originally released, and has not exactly been a ”hidden gem” in any way.

The film has spawned four remakes. The first one was a cheapo exploitation horror flick in 1959, called Terror is a Man, directed in the Philippines by Gerardo de Leon and starring Francis Lederer. This film subsequently spawned two sequels directed by Filipino director Eddie Romero. One of these was actually more of a remake than a sequel, when Romero returned to the original story with a (slightly) larger budget in 1972 (made by Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, no less). That film was called The Twilight People, and starred actor/producer John Ashley and a young Pam Grier as the Panther Woman. In 1977 the story was given a considerably larger budget and for the first time filmed as The Island of Dr. Moreau. This version starred Michael York (of Logan’s Run fame) as Edward Prendick, although now renamed as Andrew Braddock, Burt Lancaster as Moreau and Barbara Carrera as eeeh … the Panther Woman, but not really, since the filmmakers edited out all notions of her being created by Moreau. Except for a fraction of a second, where her make-up as the Panther Woman can be seen if you don’t blink. Which makes the film utterly confusing.

And of course there is the infamous 1996 remake with Marlon Brando, Val Kilmer, David Thewlis and Fairuza Balk. Thewlis (one of my favourite actors) here plays Edward Prend … err Edward Douglas, as he is apparently called now. Brando has been universally lambasted for his role as Moreau, but I watched the film the other day, and can’t honestly see why it is seen as such an outrage. OK, so he sticks an ice bucket on his head in one scene and dresses in white robes, but apart from that his portrayal isn’t any more outrageous than that of Charles Laughton’s (in fact if you want to see it as such, he is also doing a brilliant self-parody of his role in Apocalypse Now. The film also has Kilmer doing a brilliant parody of Brando.) Perhaps it was just that back in 1996 it was a pastime to see Brando so you could lambast him, as it was with Lugosi in his latter years. Well, we shall return to that film (hopefully) some time later.

In 2007 Danish writer/director Nikolaj Arcel made a fantasy adventure movie called Island of Lost Souls, but it has nothing to do with the Wells story. A 1974 Mexican film called La isla de los hombres solos (literally: the island of men alone) was released in the US as Island of Lost Souls, which, again, has nothing to do with the Wells story or the 1932 film. A number of remakes or adaptations have been announced in the last years, including a Warner Bros. production with Leo DeCaprio as co-producer and a CBS TV series, but none of the productions seem to be going anywhere fast at this moment.

Ah oh: a bit of trivia to finish off: the film is credited for coining the term ”The natives are restless tonight”, which is true – although it is a bit of a misquote, like ”Luke, I am your father”, or ”Play it again, Sam”. The original dialogue goes like this:

Ruth Thomas: [hearing chanting] What’s that?

Dr. Moreau: The natives, they have a curious ceremony. Mr. Parker has witnessed it.

Ruth Thomas: Tell us about it, Edward.

Edward Parker: Oh, it’s … it’s nothing.

Dr. Moreau: They are restless tonight.

Janne Wass

Island of Lost Souls. 1932, USA. Directed by Erle C. Kenton. Written by Philip Wylie & Waldemar Young. Based on the novel The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells. Starring: Charles Laughton, Richard Arlen, Bela Lugosi, Kathleen Burke. Leila Hyams, Arthur Hohl, Stanley Fields, Paul Hurst, Hans Steinke, Tetsu Komai, George Irving, Buster Crabbe (unconfirmed), Alan Ladd (unconfirmed). Cinematography: Karl Struss. Make-up: Charles Gemora, Wally Westmore. Art direction: Hans Dreier. Visual effects: Gordon Jennings. Produced for Paramount.

Leave a comment