A very early sound film, this 1930 US sci-fi musical comedy tried to combine Metropolis, A Princess from Mars, The Ziegfield Follies and stand-up comedy. With predictable results. Despite being the brainchild of Hollywood’s hottest musical writers, the music is dull, the science fiction worse and the comedy painfully unfunny. The film looks good, though. 3/10

Just Imagine. 1930, USA. Directed by David Butler. Written by Lew Brown, Buddy G. DeSylva and Ray Henderson. Starring: El Brendel. John Garrick, Maureen O’Sullivan, Marjorie White, Frank Albertson. Cinematography: Ernest Palmer. Produced by Lew Brown, Buddy G. DeSylva and Ray Henderson for Fox. IMDb score: 5.5. Tomatometer: N/A. Metascore: N/A.

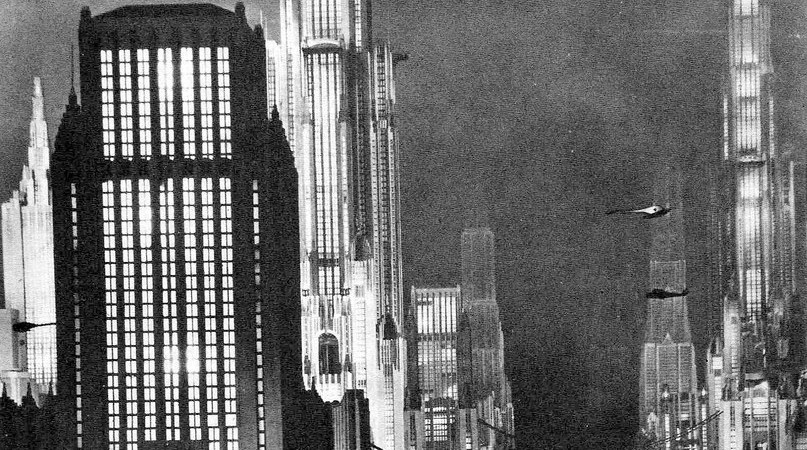

Just Imagine! In 1980 New York will have 250 stories tall art deco buildings, will be built on nine different planes and be littered with suspended roads, and everyone will have their own airplane to go out for groceries with! Just Imagine! In 1980 prohibition will still be in effect, and everyone will be getting loaded on alcohol pills! Just Imagine! In 1980 the food comes in pill form, airplanes are built on conveyor belts and even babies come from slot machines! Just Imagine! In 1980 people have letters and numbers instead of names, and governments will decide on who gets to marry who! Just Imagine! In 1980 dead people from the past can be resurrected! Just Imagine if one of those dead people happened to be 1930’s vaudeville comedian El Brendel who turns out to be an alcoholic and goes off to Mars and gets cosy with a gay captain of the Martian guard! Just Imagine what kind of film that would be!

Or, you don’t have to imagine, just watch Just Imagine, the first science fiction musical comedy, made in 1930. Or you can read this review. This film is about as bizarre as it gets. In 1930 the Great Depression had just hit USA, and people wanted light-hearted entertainment to ease their troubles. In 1927 The Jazz Singer introduced both the sound film and the musical film, and by 1930 a shitload of film musicals had been made, one of them, Sunny Side Up (1929) had been a huge hit and featured songs by a trio named Lew Brown, Buddy G. DeSylva and Ray Henderson, who were a force to be reckoned with on Broadway. They got called in to write new material for Just Imagine, a film inspired by Austrian director Fritz Lang’s futuristic masterpiece Metropolis (1927, review), the budding pulp sci-fi magazines and, more than anything, musical comedies and vaudeville.

Citizen J-21 (John Garrick) wants to marry his girlfriend LN-18 (Maureen O’Sullivan, later known as Tarzan’s Jane) – but alas, the mean MT-3 (Kenneth Thomson) has already filed for her marriage with the authorities, and since he is of higher rank in society LN-18 will have to marry him. This exposition conversation takes place above the Manhattan skyline in two hovering airplanes, no less. J-21 complains to his friend RT-42 (Frank Albertson) that he would have to advance in his career in the next three months in order to win the hand of LN-18.

Oh hell, let’s just call them Jack, Bill, Bob and Lucy. I’m getting all confused myself from all these numbers.

So, Jack complains to his friend Bill that he would have to advance in his career in the next three months in order to win the hand of Lucy, otherwise she has to marry Bob. But, says Jack – he is a zeppelin pilot. And as he already pilots a zeppelin, it’s pretty darn difficult to advance any further in that job. Enter D-6 (Marjorie White – henceforth Betsy), Bill’s girlfriend, a sparky eighties flapper with loads of spunk, who also happens to be a nurse at the clinic where dead people are revived — a modern girl. Jack comments to Bill that Betsy isn’t of his taste, as she is much too modern – he likes good old-fashioned girls. This leads to one of the most bewildering lines in movie history: ”No, I like my girls like my grandmother used to be”. This takes the Oedipus complex to whole new spheres. And sadly, this also leads to the first of many bland 1920s-styled musical numbers, as Jack picks up a guitar and sings a longing ballad about the old-fashioned girls of the thirties, like his grandmother.

“Enough of that”, Betsy seems to think while showing off her new outfit that can be folded inside-out, and drags the melancholy Jack and Bill to the lab where they are about to revive some dork who got struck by lightning in 1930 while playing golf. This turns out to be El Brendel, the hugely popular vaudeville comedian who became famous for doing a routine with a bad imitation of Swedish, and despite his stage name was completely American, with an Irish mother and a German father, and whose real name was Elmer Goodfellow Brendel. After a brief shock he starts to pop booze pills and doing excruciatingly bad jokes. Here’s a teaser:

– We’re going to Mars, says Jack.

– Take me with you, I’d like to meet your mother, replies Brendel.

Please don’t laugh so loud, you’ll wake the neighbours.

The long and the short of it is then that a professor tells Jack that he has built a space ship designed to go to Mars, and by piloting it, Jack might improve his standing with the marital judge and just make it back in time for the three month deadline. At a farewell party Bill and Betsy perform the song Never Swat a Fly, complete with choreography with fly swatters, and then Bill, Jack and Brendel (btw dubbed as Single-0) take off to Mars. Here Metropolis is switched for Georges Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902, review), and the explorers are taken to empress Loo Loo (Joyzelle Joyner, scantily clad in plastic scales, resembling a deep sea fish) and her manservant/captain of the guard, Loko (Ivan Linow, a huge man in his fifties clad in something from Conan the Barbarian meets The Flintstones).

It is quite clear that this film was made before the production code, or Hays Code, was strictly implemented, because of the not so subtly implied homosexuality of Loko, who immediately takes a liking to Brendel, who isn’t slow to capitalise on the humour of the situation: “She’s not the queen! He is!”. It is also clear that men of the early thirties were terribly frightened of women, since both Bill and Brendel stubbornly refuse to remove their clothes for bathing as long as there are women in the room – they are downright terrified of the thought. Getting undressed by a huge burly homosexual in s/m gear seems to be perfectly fine, though. There is also a brilliant scene in which scantily clad Martian women crawl around a huge mechanical idol that scoops up the near-naked girls in his mechanical arms after a short dance routine. This scene would later turn up in the first Flash Gordon serial (1936, review), and is just one of the spectacular visual elements of the film.

The explorers are then kidnapped by the evil twins of the good Martian society, led by Boo Boo and Boko (Joyner and Linow again), some not very inspired chase and fight scenes ensue, and the hopeless Brendel turns out to be the hero who defeats Boko and helps the trio return to Earth just in time for Jack to marry Lucy.

This film is a perfect time capsule for the confusing time between 1927 and 1931 when films were still getting used to sound. It was also a time when much of America had been confused by the rapid advance of technology, as well as by the female liberation that came with the suffrage and the sexual and moral liberation that gave rise to the flapper. If the god-awful songs in the film seem dated today, the only consolation is that they were dated even in 1930. By this time the first fad of musical comedies were already waning and this was definitely not the best work of songwriters and producers Brown, DeSylva and Henderson.

Silent films were an art form all to themselves, and sound films demanded a whole new way thinking. Many producers tried to imitate what they already knew of entertainment with sound, like radio, theatre and vaudeville, which was one reason as to why many vaudeville acts got stuck in the movies. For some it was a lucky break but others had their careers ruined. A vaudeville act might tour America with the same numbers for years and never have the same audience, so his or her act was always fresh. But with films the act was there for all to see, which meant that if it wasn’t spectacularly good, it was henceforth unusable.

El Brendel had originally started his show with a German accent routine. But because of the steady rise of Nazism in Germany, he was forced to change it, and for some reason came up with his character of an oafish Swede, and for some reason that is beyond me, it was hugely popular, so much that Fox decided to give him a central role in one of their most expensive films of the year. It is gruelling to watch. It is not only outdated, it was outdated at the time of Plato. The jokes are so bad they make you cringe, and joking really is El Brendel’s only talent, since he doesn’t even sound Swedish (I should know, it’s my first language).

The themes are also a strange concoction. We move about in this futuristic world with Metropolis-inspired sets, video phones and huge societal changes. But everyone still dresses like 1930, and they even behave like 1930. Women are still supposed to be meek and quiet among men, especially fathers and husbands. All people with prestigious occupations still seem to be male, and for some reason New York in 1980 is completely Caucasian. An Asian-looking doctor does flicker past the camera at one point, but there’s isn’t a single black person in the city, it seems. So we have this strange future city in which a man sits and sings a longing songs about the women of the past, and how they were good and old-fashioned. In actuality, it is all of course a representation of 1930, and the film rather looks back to the time before the Roaring Twenties, back before the flapper and the moral liberalism. In the end, although having been to Mars, where there seems to be equality (a female ruler), free love, and all sorts of good things, the explorers don’t really seem to make much of it. Although Jack has done nothing else during the film than complained about the current system on Earth, where one can’t freely choose who one marries, in the end he doesn’t give a fiery speech at the magistrate. Which is what we would normally expect from a film in which a man lives in dystopia but has seen a glimpse of utopia — the protagonist rising to the occasion in order to challenge the system. Not Jack. He simply complies with the rules, now that they are on his side. It is an awfully conformist film.

What works, though, are the sets. The film opens with the gigantic Metropolis-inspired New York skyline, built in a huge hangar by 200 people, with 15 000 light bulbs, at a staggering cost of 250 000 dollars (massive for the day). The airplanes are nicely designed, as is the spacecraft (which was later re-used in the Flash Gordon series in 1936, as were the strange looking handguns on Mars, and the scene with the Martian women and the idol). Mars is also very nicely rendered, although we are in a very fantastic world, far from the angles of Metropolis. The Martian costumes are downright stupendous. What feels so strange watching this film is that it feels like a parody of Flash Gordon, even though Flash Gordon was made six years later. The film also sports the first successful use of rear projection. The New York city skyline from this film would be reused in a number of later sci-fi films and serials.

The awesome design of the film was made by Stephen Goosson and Ralph Hammeras, both Academy Award winners or nominated. The practical miniature work was led by the duo of Willis O’Brien and Marcel Delgado, who created the stop-motion effects and creatures for films like The Lost World (1925, review) and King Kong (1933, review). This was the first film that presented the iconic electrical equipment of Kenneth Strickfaden (in the resurrection scene) – that would later go on to great fame in the 1931 film Frankenstein. Unfortunately Brown, DeSylva and Henderson produced and wrote the screenplay for the film. Director David Butler was a quite successful director all the way into the fifties, directing Doris Day and Shirley Temple in a number of films.

The actors are almost all stiff and dull, except El Brendel who is awful. The only actor that lights up the screen is comedienne Marjorie White playing Betsy. She is a mouthful, a classic hard-nosed, cheeky, independent flapper, and she brings some very much needed energy to the film, and is a complete contrast to leading lady Maureen O’Sullivan, who does little more that pout and hush throughout the whole film. And credit must be given to Ivan Linow who also adds some nice touches – although he does play the gay captain very stereotypically. But at this point you really take all the humour you can get – any humour – in this awfully unfunny comedy science fiction musical with bad music and bad sci-fi. Joyzelle Joyner is at least expressive as the Martian queen(s).

Just Imagine came at a time when studios were tentatively checking the thickness of the ice to see if science fiction could be the next big thing in the movies. While still not in any sense mainstream, SF was on the rise. In 1926 Hugo Gernsback created the first pulp magazine dedicated to the genre, which he coined as “scientifiction”: Amazing Stories. And in 1929, in the first issue of his new magazine, Wonder Stories, he first used the term “science fiction” to define the genre. (Granted, French author Maurice Renard had coined the term “le merveilleux scientifique” as early as 1909, and did as much for the recognition of science fiction in France as Gernsback did in the US.) 20th century authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs, Garrett P. Serviss and Arthur Conan Doyle joined H.G. Wells in the efforts of popularising SF stories. Along with Wells, Yevgeni Zamyatin, Karel Capek and Jack London continued the 19th century futuristic speculative tradition, while Burroughs acolytes like Alexei Tolstoy, Abraham Merritt and E.E. “Doc” Smith kicked off a second wave of space operas in the late 1920s.

But commercially things were not looking too rosy for sci-fi epics on the silver screen. The 1924 Soviet cinematic reworking of Tolstoy’s novel Aelita (review) went down fairly well with USSR audiences, but only reached a limited public in the US, where it was largely suppressed as Soviet propaganda. Metropolis (1927), while viewed as a masterpiece today, was severely chopped and altered in the US edit, leaving viewers stunned by the visuals but confused by the new plastered-on plot, which had little to do with the German original. And the British 1929 entry High Treason (review) was likewise lauded for its visuals, but murdered by both US and UK critics for its script, and even banned in some states, including New York, for its controversial pacifist message.

I can find very little information about the conception of Just Imagine, but all indications are that Fox gave writer/producer/composer Buddy G. DeSylva and his collaborators Lew Brown and Ray Henderson carte blanche to do whatever they wanted after their huge success with Sunny Side Up in 1929. While viewed mainly as a patchy curio best known for a brief performance by child star Jackie Cooper today, the musical comedy — a sort of riff on My Fair Lady — took the US by storm in 1929. Sunny Side Up was directed by David Butler, a seasoned Fox employee, and featured comic relief characters played by Marjorie White and El Brendel — all three of which were brought over to the writing trio’s next big thing: Just Imagine. Unfortunately I can’t find any information on who actually came up with the idea of making a musical comedy version of Metropolis coupled with A Princess of Mars. But all indications are that it was DeSylva, Brown and Henderson themselves.

If anyone watches this film they could be forgiven for figuring that the Martian scenes are spoofing Flash Gordon — the plot and designs are pretty much identical to the famed film serial. But he odd thing is that in 1930 there was no Flash Gordon. Gordon’s predecessor Buck Rogers was first conceived in 1928 in for in Amazing Stories, and it was turned into a cartoon strip in 1929 — the first science fiction comic, in essence. The film serial Flash Gordon didn’t premiere until 1936, and prior to that there really wasn’t anything on film with that kind of aesthetic. So while Just Imagine is clearly sending up science fiction tropes, there’s an odd paradox as it is spoofing a cinematic genre that hadn’t been born yet. The only thing really comparable to the Martian scenes in the film at the time was Aelita. But of course, there were all the illustrations and artwork done for the pulp magazines and dime novels, especially for the hugely popular stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs — mainly his Barsoom and Pellucidar series, including classics like A Princess of Mars (1912) and At the Earth’s Core (1914), series which were still going strong in the late twenties.

Some have marvelled at the way the film predicts future technology — such as television, video calls and vending machines. But many of these predictions had already been made Aelita, Metropolis, High Treason and other films — Georges Méliès predicted a sort of TV in his 1908 film Long Distance Wireless Photography (review). In fact, things such as flying cars, television, video phones, even a sort of internet, were predicted in both literature and the press in the late 19th century. Some of these predictions weren’t predictions at all in 1930 — the technology for video calls and television broadcasts already existed. It was more a question of who got the closest, from our point of view. In this case High Treason fares best: most of its predictions are now reality, even if it was a bit optimistic in predicting Skype and the Channel Tunnel to be reality as early as 1940. By comparison, Just Imagine seems to be playing their predictions mostly for laughs; such as babies coming from vending machines and all food being served in pill form. More than anything, Just Imagine resembles the futuristic postcards being made by Albert Robida and other French artists for the World’s Fair in Paris in 1900, predicting life in the city in the year 2000.

The film looks good. And it had better, since it had a budget of a million dollars, which was a lot in 1930: the most expensive US film made up to that point was Ben-Hur (1925), at a cost of 4 million dollars. Ralph Hammeras and Stephen Gossoon were so good at copying the look from Metropolis, that clips and stills from Just Imagine have repeatedly been mistakenly presented in articles and TV programs as being from the former film. The special effects are stunning for their time. The massive, distinctive Art Deco city-scape, for which Just Imagine has come to be best remembered, was built in a former Army balloon hangar by a team of 205 technicians over a five-month period. The giant miniature cost $168,000 to build and was wired with 15,000 miniature lightbulbs (an additional 74 arc lights were used to light the city from above). Over 50 shots were created with the so-called Dunning process, a bi-pack process that was used in black-and-white films for dropping actors on top of a previously filmed background — a precursor to the bluescreen effect — that used yellow light and blue backgrounds.

I think one of the reasons that some science fiction aficionados tend to have harbour an intense disliking towards Just Imagine is that it feels like a lost opportunity that set back the prospect of having science fiction taken seriously as a film genre by several decades. To be fair, critics, for some unfathomable reason, seemed to like Just Imagine. And sure, the plot wasn’t necessarily any more brainless than other Buddy DeSylva musical comedies, like Sunny Side Up or Good News (1930). It’s just that these films were just supposed to be brainless entertainment — which was actually how some Hollywood producers imagines sound movies: as a sort of extension of vaudeville. Vaudeville was, as mentioned earlier, the closest comparison some of these producers could make to sound films, if they didn’t, for example, have a background in dramatic theatre. Some of the biggest moneymakers in Hollywood during the silent era had been comedians like Fatty Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd. On the other end of the spectrum you had epics, ranging and D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), via The Ten Commandments (1923) Greed (1924) and Ben-Hur to Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings (1927). And of course, musicals were highly popular on and off Broadway.

So if you could combine all of these elements in one single product, and add the novelty of sound and music, you would be sure to have a smash hit on your hands, right? Right! And for a time it worked. Terrible pictures like the Al Jolson movies The Jazz Singer (1927) and That Singing Fool (1928) were huge successes. Hollywood hit peak musical in 1929, with classics like the afore-mentioned Sunny Side Up, as well as The Love Parade, The Broadway Melody, Show Boat, The Hollywood Revue of 1929 and many others. But movie-goers could only be swayed by lavish productions and catchy tunes for so long before they grew tired of the pointless and badly written scripts. By mid-1930 Warner started withdrawing their musicals from cinemas because of poor turnout. Just Imagine premiered in November 1930. By then, they were almost flogging a dead horse.

Vaudville had been the most popular form of mass entertainment in the US prior to the onslaught of the movies, and stood its ground, though diminished, during the silents. Those performers specialising in physical comedy, like Chaplin and Keaton, had already transitioned almost exclusively to the screen. But those who specialised in singing or spoken comedy still held vaudeville alive — until the advent of the sound pictures. Some of the biggest stars of early sound pictures; Eddie Cantor, Nina May McKinney, The Marx Brothers, Al Jolson, and indeed El Brendel, all came from vaudeville. Sound pictures more or less killed off vaudeville as mass entertainment, and ironically many of the vaudeville theatres were converted into movie theatres. And as a result, the early sound musicals also tend to have a feeling of vaudeville — separate schtick acts, musical numbers and dance routines barely tied together by the thinnest of plot.

The problem with Just Imagine is that it sort of tries a bit too hard to strive for a coherent plot in order for it to get away with being a vaudeville act on screen. Once you’ve invested over 150 000 dollars (a full budget for a B-movie) in creating futuristic cityscapes and Martian landscapes and actually tried to cook up a political system of the future — which is essential to the plot — you’re simply not allowed to reduce the film to fly-swatting routines and bad puns. The fly swatting number is sort of adorable, but what the hell is it doing in this film? The same can be said for El Brendel’s hat switch act. Sure, it’s mildly funny as a vaudeville routine (with emphasis on mildly), but completely out of place in the movie.

There’s also a strange paradox underlying the entire premise of the film. The driving force of the film is the fact that according to the laws of 1980, Jack isn’t allowed to marry Lucy, because his rival is more distinguished than he is. And Lucy, in this new world of rules and regulations, has very little power in choosing her husband (the main problem does seem to be that she has agreed to two different marriage proposals, but that’s really beside the point — once she has agreed to one proposal, she can’t get out of it without the proposer being challenged by someone of higher rank in society, even if she realises the first guy is a dick). So, on the one hand risks his life in an insane attempt to fly to Mars because he has to fight a technocratic system that has turned people into numbers and more or less eradicated their civil liberties. Babies come from vending machines, food and alcohol is not allowed for pleasure, even love is now a bureaucratic procedure. El Brendel, Jack and Bill spend most of the film longing back to “the good old days” when one could have a proper roast beef and a frothing jug of beer, and indeed choose whom to marry or not marry. But on the other hand, Jack also spends most of the movie telling everyone that the reason he loves Lucy is that she’s “an old-fashioned girl, like his grandmother”, homely and conservative, and not at all like the “liberated” women on 1980. But from what we can see on screen, there’s nothing liberated at all about women in 1980. Sure, Betsy’s a bit promiscuous and a loud-mouth, but that’s the 1920s flapper for you. Chances are Jack’s grandmother was just as “liberated” as Betsy. And, as stated above, when Jack comes home after having witnessed the actually liberated society on Mars, he is perfectly happy to go along with the current system, as long as it plays in his favour.

The biggest reason for Just Imagine’s poor box-office draw probably wasn’t its garbled sci-fi setting, but the fact that audiences had grown tired of badly written musicals — but it surely didn’t do anything to help promote SF as a viable investment in the eyes of Hollywood producers. Naturally, the failure of science fiction to become recognised as A-movie material wasn’t entirely the fault of Just Imagine. Despite a handful of valiant efforts in the twenties and thirties, all of the big budget science fiction films made during the era — if not flopped, then at least didn’t become the successes their producers had hoped. Science fiction did slowly march into the movie mainstream through Hollywood serials in the thirties — but as kiddie stuff, and more thanks to comic strips than science fiction novels. Another genre in which SF blossomed was the horror movie, specifically in Universal’s monster franchise, from Frankenstein (1931) onward through mad scientists, invisible men and radiated monsters. But strictly as B-movies.

But let’s return to my previous statement: The intense disliking some sci-fi fans harbour towards Just Imagine is that it feels like a lost opportunity. They had the budget, they had the sets, they had a decent enough director on-board to do something more than what they did. We could have lived through a couple of lame musical numbers and a few bad puns if the film would just have had something more in the way of a script. Of course, this was part of the problem: there really was no such thing as a screenwriter for talkies in 1930. Previously people who wrote even successful films didn’t have to have a clue as to how to write dialogue or how to carry a story through words, rather than images. A director could often start out with a simple synopsis no more than a page long, and make it into a movie of an hour and a half. So either producers brought in theatre writers, who would write static, talky scripts without any regards to the visuals of cinema, or people who had previously only written synopses and title cards had to fly by the seat of their pants.

Just Imagine wasn’t a complete financial disaster, and Fox eventually managed to cover its costs by selling clips of the futuristic cityscapes, as well as props and sets. As stated, the pre-Busby Berkeley dance scene in Just Imagine turned up in an episode of Flash Gordon, as did the spaceship from the movie. And during the revival of the Hollywood musical only three years later (thanks almost solely to Busby Berkeley’s amazing choreographies) there was in fact a last attempt to make an SF A-lister in Tinseltown. And once again it was Fox that was at it: This time the studio revamped the futuristic silent comedy The Last Man on Earth (1924, review) into a full-blown musical called It’s Great to Be Alive (1933), with music by later Oscar winner Hugo Friedhofer and cinematography by the renowned Robert H. Planck, and with Gloria Stuart in the female lead. Like its predecessor, this was long considered a lost film, but like The Last Man on Earth, it has been rediscovered and restored by MoMa. It’s Great to Be Alive was screened for the first time in decades in 2017, but a version for home viewing is as of yet still forthcoming. I wouldn’t get my hopes up though: MoMa has sat on a print of The Last Man on Earth since 1971, and it still hasn’t been released for home viewing.

Of the three producers/writers of Just Imagine, Buddy G. DeSylva, the lyricist of the group, was the most prominent in Hollywood. He started his career writing music for Broadway, in particular for Al Jolson, in the late 1910s, and frequently collaborated with George Gershwin. It was in 1925 when he teamed up with Russian-born Lew Brown (Louis Braunstein) and Ray Henderson, and for five years they were the most sought-after songwriting team for both Broadway and later Hollywood. DeSylva was chairman of ASCAP for eight years, and co-founded Capitol Records in 1942. The trio’s collaboration ended when DeSylva in 1931, after which DeSylva became a full-time producer at Fox . After a short stint at Universal in the late thirties, he became executive producer at Paramount in 1941, and stayed there until his retirement in 1944, overseeing the production of many of the studio’s biggest films. DeSylva co-wrote a number of classic songs, including Sonny Boy, Magnolia, California, Here I Come, Button Up Your Overcoat, Avalon, If You Knew Susie, You’re the Cream in My Coffee, and many more, all in all his songs are credited to have featured in over 400 movies or TV shows. In reality though, the number must be in the thousands. Younger viewers may recognise his handiwork from the theme song of The O.C. While not a direct cover, the theme song California borrows enough elements from California, Here I Come to credit DeSylva and Al Jolson as co-writers.

Lew Brown and Ray Henderson were more traditional songwriters than DeSylva, and continued collaborating until 1933, when they also went their separate ways, both continuously successfully writing music for both stage and film. DeSylva was nominated for an Oscar for the song Wishing from Love Affair (1939) and Lew Brown for That Old Feeling from the film Vogues of 1938 in 1937. Brown’s perhaps most successful song came about late in his career, with Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree, which was turned into a gigantic hit by both Glenn Miller and the Andrews Sisters during WWII. The song has been inducted to the Grammy Hall of Fame. In 1956 Michael Curtiz directed the film The Best Things in Life Are Free, about the collaboration of the legendary trio. However nothing — and I say: nothing — of this brilliance is on display in Just Imagine.

Director David Butler came from a theatre family in San Fransisco and started his career as an actor — he appeared in over 70 films, mostly in smaller roles, between 1910 and 1929. He made his directorial debut at Fox in 1927, and directed over 30 films for the studio during nine years, mostly comedies. During he late forties and fifties he directed a number of films starring Doris Day, best remembered of which is Calamity Jane (1953). He directed over 50 films, and in the fifties and sixties worked mainly in television. In 1955 he directed all 26 episodes of Captain Z-Ro, an educational children’s show that featured a professor who invents a time machine so he can visit different historical events. The series played out a bit like a precursor to Dr. Who, which premiered on British TV in 1962. Apart from this Butler had very little contact with science fiction apart from Just Imagine.

Set and miniature designer Ralph Hammeras is better known as a special and visual effects creator, and later did effects for such productions as Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and Cleopatra (1963). He’s also a science fiction legend, having created effects films like The Lost World (1925, review), Disney’s marvellous 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954, review), as well as such low-budget cult classics as The Giant Claw (1957, review), The Black Scorpion (1957, review) and The Giant Gila Monster (1959). Just Imagine brought him his second out of three Oscar nominations.

Stephen Goosson was a more traditional art director, having worked on silent classics like Jackie Coogan’s Oliver Twist (1922) and Lon Chaney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), and went on to do designs for such evergreens as It Happened One Night (1934) and Holiday (1938). He also worked on the sci-fi films Black Oxen (1923, review), Flight to Fame (1938) and the Lucille Ball comedy Her Husband’s Affairs (1947) — in which the sci-fi element consists of a hair-growth formula.

To be fair to actress Maureen O’Sullivan, whom I ribbed earlier for pouting her way through the film, she did not have much to work with, and later showed that she was indeed more than just a pretty face. 1932 she got her big breakthrough playing opposite Johnny Weissmüller in Tarzan of the Apes, and reprised the role six times. In the thirties and early forties she had a number of high profile roles in films like The Thin Man (1934), Anna Karenina (1936) and Pride and Prejudice (1940). She took a break from acting in 1942 to tend to her sick husband, director John Farrow, and her family. One of her six children, renowned actress and activist Mia Farrow, was born in 1945. O’Sullivan returned to acting in the fifties, both on stage and in film, and one of her most famous later roles was in the star-studded Woody Allen film Hannah and her Sisters (1986), with Mia Farrow playing the title role. Farrow was also Allen’s long-time girlfriend (and there was the scandal with Allen marrying Farrow’s adopted daughter, but let’s not get into that now).

Perhaps the best part of the film is the feisty Canadian singer, dancer, comedienne and all-round likeable character of Marjorie White an extremely talented artist who died way too soon. According to the Manitoba Historical Society she was born as Marjorie Guthrie in Winnipeg in 1904 (although Fox presented her as being born on 1908). She began appearing on stage as a dancer and singer at the age four: “In 1915, she became an original member of A. H. Smith’s Returned Soldiers’ Association Juvenile Performers, which put on shows in Manitoba and beyond to raise funds for returned soldiers and their families. The group was renamed the Winnipeg Kiddies in 1919. When the Kiddies disbanded in December 1921, several of its performers went into vaudeville, including Guthrie and Thelma Wolpa as a two-woman song and comedy act. Though not related, they billed themselves as the White Sisters and had success on the Keith vaudeville circuit. When Guthrie married fellow tour performer Eddie Tierney in 1924, they started a new act called Guthrie and Tierney before settling in New York.”

She appeared on Broadway in several musicals between 1926 and 1929, when she and her husband moved to Hollywood. In August 1929, she signed on as a contract player with Fox Studios. All in all White appeared in nine films for Fox in 1929 and 1931, four of them musicals. The blog Vitaphone Variety writes: “Although a key figure in Happy Days (1930) — with the film’s minstrel show/revue portions being hung upon a thread of a plot led by Marjorie White, it’s New Movietone Follies of 1930 that allows for the one and only spotlight performance in her film appearances. One of many elaborate musical sequences in the film,’Talking Picture Queen’ presents White as a young nobody arriving at the studio gates, eager to impress studio executives who pleads ‘How I long to be synchronized!’ Quickly advancing through the required course of voice and dance lessons, she emerges a full blown talkie diva at last — only to be joined by a thundering herd of dancers who share her moment of glory.”

At Fox she also appeared in a substantial role in the classic detective movie Charlie Chan Carries On (1931), with Swedish-American Warner Oland playing the Chinese detective mastermind, and with John Garrick as the second lead, and appeared in an uncredited role in another Charlie Chan movie, The Black Camel (1931), this time with Bela Lugosi as co-lead, and with another horror legend, Dwight Frye, in a bit-part. She teamed up with Lugosi for the second time, again in an uncredited bit-part, in Women of All Nations (1931). While her role was small, she fared better than a young Humphrey Bogart, who was edited out of the film altogether.

For one reason or the other, White’s contract with Fox ended in 1931, and she went freelance, doing a celebrity cameo in a Universal short, after which she got cast as the female lead in the First National Pictures movie Broadminded, a low-budget mystery comedy — and a third collaboration with Bela Lugosi. This time she even had scenes with the Hungarian vampire, fresh off his success with Dracula (1931), and in the prime of his career. After this she was cast in a supporting role in an actual A-list drama movie, The Possessed (1931), starring Joan Crawford and Clarke Gable, for MGM. She returned to Broadway for a musical, Hot-Cha, in 1932, but came back to Hollywood thereafter. In 1933 she was awarded another female lead in the RKO film Diplomaniacs by the popular comedy duo Wheeler and Woolsey.

The next year White was cast as the female lead in Woman Haters, the first short film that The Three Stooges made for Columbia Pictures — however it was White that got top billing, which seems to indicate that Columbia was about to launch her as a major star of the studio. Alas, White’s promising career ended with her death in a car accident, at only 31 years old, shortly after the film was completed. According to the blog Vitaphone Varieties White “lit up the screen with a manic energy and distinct personality of the rare sort that didn’t lose audience favor as quickly as it would with Winnie Lightner or even White’s frequent co-star, El Brendel.” The petite 4’10 (150 cm) White has the same sort of tomboyish energy as legendary flapper Clara Bow, and a loud voice to go with it, as well as some serious acting chops. Unfortunately she all but disappears from Just Imagine the moment El Brendel & Co take off for Mars.

Another interesting actress in the film is Joyzelle Joyner, who is one of the people who make it at least temporarily an enjoyable experience as the Martian queens Loo Loo and Boo Boo. Decked out in her deep sea fish-inspired scaly dress, she does a wonderfully comical pantomime, courtesy of her training as a dancer. Joyner made headlines in 1927, before her film career had really even taken off, but unfortunately because of tragic circumstances. Joyner, still an unknown dancer, entered the film business around the age of 19 or 20 in 1924 or 1925 doing uncredited extra work, often as a dancer, and not seldom in provocative roles. Her alluring performances were starting to get noticed, and as a result she was shot by her estranged and jealous husband. According to the movie blog Pre-Code Madness (which I won’t link to, as my Chrome warns me that it’s potentially unsafe):

“Joyner, now aged only 22, was married to Dudley V. Brand who, jealous of his wife’s acting career, wanted desperately for her to behave like a traditional housewife instead of a Hollywood sex symbol.”

According to the news agency AP: “Miss Joyner, wounded in her left arm when her estranged husband, Dudley V. Brand, shot through the closed door of her bedroom, was taken to a hospital where physicians said her injury was not serious. Police were seeking Brand, who fled immediately after the shooting. After two shots had been sent through the door of Miss Joyner’s room, her 19-year-old brother, Clarence wrested the pistol from Brand’s hand.”

Joyner promptly divorced Brand and subsequently married film director Phil Rosen in 1929 and, without any marital restraints, continued her film career ambitions. Despite her “exotic” looks which earned her so many roles as Asian or Arabian dancers, Joyzelle Joyner was born and bred in the US, in Alabama in 1905. Little has been written (that is available online) about her life before her film career, and she did indeed enter the film business at a relatively young age. Joyzelle was actually her real first name – her parents reportedly made it up. By 1928 she was receiving credited minor parts in substantial films, and was starring in short movies, often as a harem girl or exotic princess. Her role in Just Imagine was the most prominent to date, even if it didn’t immediately boost her career. She did, however, start getting bigger parts in 1932, when she appeared in no less than three feature films – be it that two of them were directed by her husband Rosen, who at the time was a very prolific western director. In the 1932 cheapo western Whistlin’ Dan she was even allowed to play the female lead opposite cowboy star Ken Maynard. However, it was her third role, albeit smaller, that made headlines. Again, according to Pre-Code Madness:

“Directed by the king of the religious epic, Cecil B. DeMille, The Sign of the Cross (1932) starred Claudette Colbert, Fredric March and Elissa Landi in a story set in Ancient Rome during the reign of Emperor Nero. Like many of DeMille’s Precode films the original print focused mainly on the struggle between purity and sin and included many sexually charged and provocative scenes. Joyner, portraying immoral dancer Ancaria, is prominent in one of these shots when she is encouraged by Marcus Superbus (March) to dance around Mercia (Landi) and perform the song ‘Dance of the Naked Moon’ in order to “warm her into life”. DeMille was pressured by the Hays Office to remove the sequence but he refused and left it in the final 124 minute cut. The scene – as well as several gladiatorial fighting and nudity parts – were removed from the reissues following the 1934 code changes. However, they were replaced MCA-Universal for the 1993 edition.”

1932 turned out to be the top year of Joyner’s career. She did have a couple more featured roles, but was still mainly cast as the dance interlude in cheap B-movies. Apparently she realised that her dream of becoming a bona fide movie star wasn’t going to happen, as she retired from the screen in 1935. What became of her after this, I can find no information on, only that she passed away in 1980, the year that Just Imagine was set in. At the movie’s 50th anniversary the same year she and Maureen O’Sullivan were the only cast members still alive. Ironically, she passed away just one week after the anniversary. To be honest, film history probably isn’t poorer for the fact that Joyner never made it to the big time. A mediocre dancer, her exotic sex appeal was enough to carry her through snake-like “oriental” dance numbers, some faux-flamenco and broad pantomime numbers such as that of the Panther Lady in Wild People (1933). Still, her dancing was better than her acting, as is evident from her actual speaking parts in Whistlin’ Dan (not that Ken Maynard was any better) and the odd genre mash House of Mystery (1934). For my money, her best turn by far was actually in Just Imagine.

Ivan Linow’s real name was Janis Linaus, and her was a Latvian wrestling champion who later turned to acting, very much like the later B-film legend Tor Johnson. He appeared in over 50 films in the States, and is perhaps best known from the 1929 sound remake of Tod Browning’s classic Unholy Three, starring Lon Chaney, Sr.

Frank Albertson was a well-employed character actor, mostly playing supporting roles – perhaps best known from Fritz Lang’s Fury (1936), Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). He also appeared in Lon Chaney Jr’s sci-fi horror debut Man Made Monster (review) in 1941. Hobart Bosworth, playing the professor Z-4, who builds the space ship, was a famous theatre actor and one of the biggest names in early Hollywood, starring in what is believed to be the first adaptation of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1908, for example.

Mischa Auer, a Russian émigré, would later become a staple in comedic roles, and playing different European nationalities, often in high profile films, like My Man Godfray (1936), for which he was nominated for an Oscar, and the Best Picture winner You Can’t Take it With You (1938). He appeared as the villain Hanns Krug in the 1932 horror film The Monster Walks, and in 1933 he appeared alongside the future Flash Gordon – Buster Crabbe – in a Tarzan serial. He was directed by the early sci-fi experimentalist René Clair (The Crazy Ray, 1924, review) in 1945 in his adaptation of Agatha Christie’s And then There Were None (1945).

Janne Wass

Just Imagine. 1930, USA. Directed by David Butler. Written by Lew Brown, G.G. DeSylva and Ray Henderson. Starring: El Brendel. John Garrick, Maureen O’Sullivan, Marjorie White, Frank Albertson, Hobart Bosworth, Joyzelle Joyner, Ivan Linow, Mischa Auer, Kenneth Thomson. Art & design: Stephen Goosson, Ralph Hammeras. Editing: Irene Morra. Cinematography: Ernest Palmer. Produced by Lew Brown, G.G. DeSylva and Ray Henderson for Fox.

Leave a comment