With a star cast, this 1954 Disney blockbuster is regularly seen as the best Jules Verne adaptation of all time. Shot in majestic Technicolor, it is a magnificent adventure film with groundbreaking special effects, despite a so-so script. 8/10

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. 1954, USA. Directed by Richard Fleischer. Written by Earl Felton. Based on novel by Jules Verne. Starring: Kirk Douglas, James Mason, Paul Lukas, Peter Lorre. Produced by Walt Disney. IMDb: 7.2/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 89/100. Metacritic: 83/100.

Underwater shenanigans was a thing in science fiction films in 1954, with Universal rolling out its final (belated) ”golden era” movie monster in Creature from the Black Lagoon (review) and Roger Corman making his production debut with Monster from the Ocean Floor (review). One of the reasons for this fad was the fact that a piece of technology had recently been unveiled that revolutionised underwater photography: scuba gear. But another, perhaps even greater reason was that movie lovers around the world were anxiously awaiting the Christmas release of Walt Disney’s mega-production 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

With a star cast, the adaptation of Jules Verne’s classic novel was the first live-action film to be shot on Disney’s new home studio, the second movie in history to be filmed in widescreen Cinemascope, and wound up being one of the most expensive films in movie history at that point with a final price tag of 5 million dollars. Disney had never attempted anything even close to this scale: no-one had ever attempted anything even close to this scale. Rivalled only by two European productions, Metropolis (1927, review) and Things to Come (1936, review), 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was the most expensive science fiction film ever made. Not only would the production be costly, but Disney had no experience with making live-action movies at this scale, even though the studio had five live-action films under its belt, including another maritime adventure; Treasure Island (1950).

But the gamble paid off. 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was released to rave reviews and packed movie-houses, becoming the second-highest grosser of 1955. Today it is considered by many as one of the best, if not the best, Disney live-action film, with competition mainly from Mary Poppins (1964), Pirates of the Caribbean (2003), and recently the new sequels in the Star Wars saga. To this day it is generally seen as the best movie adaptation of a Jules Verne novel.

The story should be at least generally familiar to most readers of this blog, either from this film, other adaptations, the novel itself or simply cultural assimilation. Prof. Aronnax (Paul Lukas) and his apprentice/valet Conceil (Peter Lorre) are hired by the US government to investigate the strange scuttlings of several ships off the Pacific — claimed by survivors to be caused by a giant sea monster. During their expedition, their ship spots the “monster” and fires upon it, after which it turns on their vessel, rams and sinks it. The only survivors, Arronnax, Conceil and master harpooner Ned Land (Kirk Douglas) are picked up by the “monster” — which turns out to be a revolutionary, giant submarine, powered by some strange new technology; nuclear power is never mentioned but the hints are clear enough, this being a fifties SF movie and all. The ship is commanded by the mysterious Captain Nemo (James Mason), who take on the three as “guests” thanks to his admiration of the famed marine biologist Prof. Aronnax, with whom he hopes to share his secrets. A fugitive from the law and the world, Nemo has made his home under the seas, which provide him and his crew with all they need. Gradually it is revealed that Nemo was once a slave labourer under “that wretched nation” (which one is never made clear), and saw his masters kill his wife and child. Disillusioned with the “civilised” world, he hid inside his volcanic lair with other former slaves, and contemplated the secrets of nature, building the Nautilus, which he is now using to exact his revenge on the evil war merchants and generals of the world. Fuelled by his hate and grief, Nemo’s world view is one of black and white. Civilisation with its corruption, unjust laws, greed and hunger for power is poised against the serene, natural order of the underwater world. Nemo’s secrets about (atomic) power and the life aquatic might solve all humanities’ problems regarding sustainability and overpopulation — but as long as they might be used for destruction rather than good, he refuses to divulge them. This is why he has not killed Aronnax and his friends — his hope is that the Professor might be the one person in the world to understand him, and he hopes to make Aronnax his spokesperson on dry land. Aronnax, while condemning Nemo’s brutality and refusal to follow the laws of men, finds his vision for the future nonetheless enthralling. As the story progresses, the future of Nemo and all of the crew and passengers on the Nautilus hang on Aronnax’ decision to support or defy the charismatic captain.

Around this rather bleak core story Disney has built an entertaining and light-hearted adventure yarn. The driving forces behind the mirth and lightness in the film are Kirk Douglas and Peter Lorre, two of the biggest stars of the screen in their day. Douglas’ Ned Land takes his cues from Errol Flynn, as he saunters around the ships, in or out of his tight-fitting sailor’s shirt, guitar in one hand and harpoon in the other, always ready to either break into song or break someone’s skull. Land is determined to escape, preferably with some of Nemo’s amassed gold in his pockets, be it in a row boat across the Pacific or through a cannibal-infested island. Peter Lorre, eternally typecast as sadistic villain thanks to his role as a child molester in Fritz Lang’s masterpiece M (1931), relishes the chance to play comic sidekick as Conceil. Pulled between the warring wills of Aronnax and Land, Conceil also serves as the identification marker for the audience. However, the real star of the comedy team is Esmeralda, Nemo’s tame seal who becomes a constant companion to our two stooges as they sneak around the submarine looking for clues and means of escape.

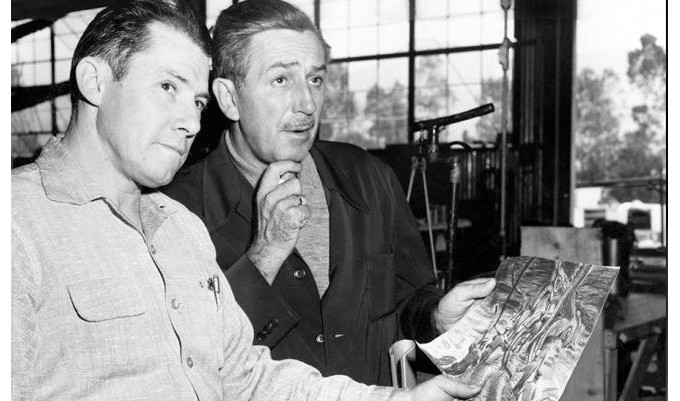

Walt Disney had long harboured a desire to turn 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea into a film, and was able to lease the only Cinemascope lens in Hollywood, owned by 20th Century-Fox. Initially he thought of making a short underwater movie on the subject, but after seeing the first test shots he decided to go all the way and make a full-length feature film. Early on he assigned Harper Goff to start designing the central set-piece, the Nautilus, and other aspects of the movie. Goff was a set designer who had worked on such historical epics as Captain Blood (1935), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), Sergeant York (1941) and Adventures of Don Juan (1948). In 1954, he had long been a part of Disney’s artistic team. Unfortunately the credits of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea read ”production developed by …” instead of ”production designed by …”, which meant that he wasn’t eligible for an Oscar nomination. So when the movie won an Oscar for best art direction, the statue was picked up by Goff’s assistants, art director John Meehan and set designer Emile Kuri.

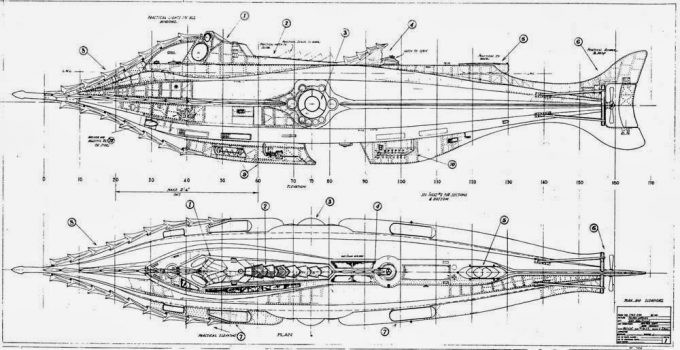

Initially Disney and Goff clashed over the film’s look. Disney wanted a sleek, sci-fi age submarine, while Goff wanted it to look as it was actually made in 1870. When Disney saw Goff’s final design of the Nautilus, he relented, and the rest of the film then followed suit, making 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea something of a steampunk pioneer, informing the design of countless Jules Verne movies to come. Goff figured that Nemo would have built the ship at his island lair, using plate steel and rivets. The design was based on a mix between a crocodile and a shark. The glowing cockpit protruding above the water-line was inspired by a crocodile’s eyes, and the jagged, riveted hull represented a croc’s scaly skin, while the sleek, curved silhouette was meant to resemble the majestic shark. Goff further figured that a submarine wouldn’t wow audiences in the fifties, and instead set about creating the most opulent, interesting interior he could find. Nemo’s cabin is a giant hall draped in wine-red velvet and teak, lined with books, art, and bottles and jars with scientific specimens. The central feature is the large circular window with a mechanical iris for a shutter. Brass and copper tubings, gauges and machinery fill the rest of the Nautilus.

Disney’s choice of director was rather surprising, as he went for Richard Fleischer, but not only because Fleischer hadn’t made any films that would qualify him for such an ambitious project. The young director had made a number of shorts and about a dozen of rather anonymous feature films. But he was also the son of Max Fleischer, famed animator and once Disney’s most fierce competitor, who was booted out of Paramount in the early forties, thus giving Disney more or less monopoly on feature-length animation films. Fleischer was known for his resentment of Disney, and Richard actually had to ask for his father’s permission to work for his old rival. To his credit Max replied: ”That’s absolutely fantastic. Your career is your career and you must do that film. Tell Walt that I think he’s got very good taste in choosing you”, at least according to Cinemafantastique, quoted by horrornews.net. According to Cinemafantastique, Richard further states that this lucky coincidence also helped mend fences between Max and Walt, who eventually became good friends.

Fleisher brought with him screenwriter Earl Felton, who had done the scripts for his two previous films. Fleischer then had the difficult task of turning a talky and disjointed book with a meandering plot into an action-packed but child-friendly script. As with many novels in the 19th century, Vingt mille lieues sous les mers: Tour du monde sous-marin was first published (1869-1870) in serialised form, which accounts for the peculiar structure of the book. This is the case with many of Verne’s books. As a kid, I read my first Jules Verne book, The Mysterious Island, at the tender age of 7, and immediately fell in love. But I had a hard time getting through 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, because for long stretches of time it seemed to be going nowhere. Once Land, Aronnax Conseil were aboard Nautilus, they seemed to be drifting at random from one place to another. True, there were exciting moments, such as the fight with the giant squid and the attack of the natives, but these were distractions that added little to the actual story, which was the submarine visiting place after place: the underwater gardens of Nemo, the depths of the ocean, the South Pole, the sunken city of Atlantis, and so on. All manner of marine life, biology, marinology were explained at length and in detail. The book was basically a fictionalised travelogue, more than an adventure novel. And instead of the rather straightforward and up-beat camaraderie that I got in The Mysterious Island, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea instead served up a much darker themes, complex characters and political and philosophical depths that I don’t think I was ready for at nine or ten, when I read the book. I put it aside halfway through and re-read it some years later.

Richard Fleischer is quoted as having said that the main aim was to create some sort of a linear story out of the book, and he and Felton chose to go about treating the three protagonists as prisoners aboard the Nautilus. The main driving force of the film would be Ned Land and Conseil trying to escape. This isn’t quite the way it goes in the book, but close enough as to not be completely out of place; in the book Ned Land does at one point stage an escape attempt, and the thought of escape is always there in the background in the book. The other major decision was to focus on Captain Nemo, and let the other three characters remain rather one-dimensional. So Aronnax becomes the movie’s stable voice of reason, admiring Nemo’s genius and his contribution to science, but scalding him for his misanthropy and his blind striving for revenge on a world that deprived him of all he loved. Ned Land is part dashing swashbuckler hero, part comic relief. Conseil is written as more or less as a blank slate for Aronnax and Land to play off, and the part is more informed by the decision to cast Peter Lorre than anything in the script. Lorre does a submissive valet type, milking the audience for laughs every time he gets the opportunity.

Fleischer and Felton knew the audience wanted to see the most iconic scenes from the book: the giant squid, the attacking natives, the underwater garden and the underwater burial, and inserted all these as central set-pieces to write the rest of the plot around. They also added a partly new ending to the movie, as Nemo takes them to a James Bond-like base inside a volcano, where he shows off his lab and his nuclear reactor. And here is where the final climax takes place, which is partly derived from the ending of The Mysterious Island, where, in the book, Nemo makes a surprise appearance. The downside of this approach to screenwriting is that it is easy to get a very episodic movie, where the characters are simply transported from one big action scene to another. The idea of having Land and Conseil planning an escape throughout the movie does partly solve this problem, but not entirely. Even if the viewer isn’t familiar with the story, they sort of know that there won’t be an escape, because this is the film that takes place in a giant submarine, isn’t it? So the actual thread that runs through the whole film is the trio’s efforts to figure out who Captain Nemo is and what he is planning.

And here Felton has succeeded ten-fold in creating an enigmatic, fascinating and scary anti-hero/villain in Captain Nemo. Some of the captain’s mystery from the book is dissolved by having him give his backstory rather early on – in the book he only alluded to such a thing. His actual backstory and motivation was revealed in Verne’s later book The Mysterious Island, and isn’t quite the same as in the film. But the central premise is the same: Nemo is a brilliant man without a country, who has lost faith in humanity. In the book he attacks ships rather at random, bringing down both merchant vessels and war ships in an attempt to disrupt the war-hungry and corrupted powers that be. Both the book and the movie portrays him as an anarchist and pacifist, killing thousands in order to prevent the death of millions in futile wars and struggles. He shuns the world, and has instead created his own perfect society in the peaceful depths of the sea. Once willing to share all his knowledge with the world, he has now grown cynical and bitter, and fears that humanity isn’t worthy of his secrets.

The film takes a slightly different slant on this, making Nemo a bit more optimistic. Without saying it out loud, the movie makes no secret of the fact that Nemo has discovered nuclear power (which despite popular myth isn’t the case in the book). Nemo hopes that the world might one day be ready for his potentially destructive secret, and harbours plans that Aronnax may be the one to deliver his discoveries to the rest of humanity. So while the Nemo of the books has already given up on his fellow man, Nemo in the film still retains a sense of hope, which does make for a little bit of a more nuanced character. Another small, but politically significant change is that Nemo of the film seems to be harbouring a specific grudge toward a specific (unnamed) nation. Here’s clearly the screenwriters’ attempt at allusion to the cold war, even if it doesn’t make a lick of sense from a historical perspective.

Of course the real genius was casting James Mason in the role of Captain Nemo. At the time, Mason was one of the biggest movie stars in the world, and this was the first time that a major Hollywood nobility was to play in what was basically a children’s movie. It cannot be stated with too much emphasis how brilliant Mason is in the role, perfectly channelling the brooding, half-mad genius, behind whose dark eyes one can almost literally see the conflict he struggles with. Here is a pacifist turned vengeful misanthrope by an unspeakable tragedy. While cursing colonialism, slave trade and war profiteering, he has no qualms about destroying vessel after vessel to achieve his aim. Many other actor would have succumbed to hamming in a juicy role such as this, but Mason’s performance is understated rather than overstated, seemingly bursting at the seams like a pressure-cooker, but reserving his rage for a few, effective outbursts. As IMDb user Jim Beaver writes: ”His mellifluous voice and an uncanny ability to suggest rampant emotion beneath a face of absolute calm made him a fascinating performer to watch.”

An even bigger star than James Mason in Hollywood in 1954 would have been Kirk Douglas. Although a hugely popular actor, Douglas perhaps felt he was missing out on the real top parts in the business at the time. Knowing the film would be a thundering success, Douglas came to Disney with a list of demands to enhance his pull as a leading man for future movies. In the opening scenes of San Fransisco he insisted to be courted by two girls at the same time. He demanded a chance to sing in the movie, resulting in the faux-shanty A Whale of a Tale on the deck of a ship soon to be sunk by the Nautilus, and made Fleischer add more scenes of him fighting. Well, you don’t say no to Kirk Douglas.

There is no denying the star power of Douglas, lighting up the screen every time he is in a scene. Few actors in history have been been graced with such charisma, and his broad-chested, square-chinned blonde apparition doesn’t hurt. For emphasis, he wears a sailor’s t-shirt three sizes too small, which he takes off to further reveal his physique every chance he gets. And check out the ass shake he does to the camera during his song number. As master harpooner Ned Land he turns up his inner Disney swashbuckler to the max, making him a favourite with the kids. Leaping staircases, dealing out upper-cuts and swings left and right, he chews up the scenery like there was no tomorrow. He plays his Ned like a broad cartoon character, even going cross-eyed before falling face down in a puddle of mud when hit on the head. He half-shouts all his lines and all but winks at the camera. But in all honesty, one should remember that this film was supposed to cater to a young audience, and amidst all the violence and the dark subject-matter, it certainly doesn’t suffer when introduced with some jolliness and humour. The introduction of the pet seal Esmeralda as Land’s one true friend is such a cheap Disney trick, but what’s not to love about it?. And there is no denying that the scene where Land accidentally drinks Nemo’s prized rare fish collection, when going for the medical alcohol it’s preserved in, is hilarious (there’s quite a lot of boozing in the movie for a kiddie film). But to an adult viewer, Douglas’ character does seem a little too cartoonish, especially compared to the grim Mason and the collected Lukas. In his defence, he does have a couple of good dramatic scenes as well. And few people did action as well as Kirk Douglas in the fifties. Aside from Burt Lancaster.

If the movie turns the stern, principled Ned Land into a comic relief, then Paul Lukas’ Professor Aronnax is made into a rather wishy-washy character. In the book, the meeting of Aronnax and Nemo is a clash of intellects, with Nemo keeping the upper hand because he commands the Nautilus. In the movie Nemo is like a crushing wave that would sweep away Aronnax like a bobbing cork in any situation. This does lend some dynamic to the film, as it gives Aronnax the opportunity to flip-flop on the subject of Nemo, and gives both Nemo and Ned Land bigger exposure. But it also completely switches around the dynamic of the imprisoned trio, turning Land into the de facto leader, which is perhaps appropriate for an action movie of this kind.

The character that has undergone the biggest change, however, is that of Conseil. A young boy in the book, he is now replaced with the 51-year old Peter Lorre, a veteran of slimy villainous roles, but with a deep love for comedy, that he did whenever the chance was offered.

Of course the thing that is missing from this movie is women. Apart from the two floozies that Kirk Douglas sandwiches himself between in the opening scenes, there’s not a single female in the film. However, this is the way the book was written, which in itself was reflection of the times. In fact, most of Verne’s books were devoid of women, since women seldom took part in explorations in the 19th century, and perhaps because Verne himself thought that adventures were no place for women (although he does include them in some of his books, like Around the World in 80 Days, In Search of the Castaways and the less known Mistress Branigan, where the protagonist is, in fact, a woman). And in a way it is perhaps better, then, to adhere the book than to artificially try to jam in a woman into the story to serve as romantic interest, damsel in distress and comic relief, which unfortunately was often a woman’s lot in science fiction and adventure movies of the fifties (and sadly, to this very day).

Should one further want to elaborate on the political correctness of the movie, one could point out that the only people of other ethnicity that Caucasian in the film are bloodthirsty natives or slaves. Despite the movie’s criticism of colonialism, it has no problem with white-washing the Indian Captain Nemo. His crew is all-white as well, even though one could expect that Nemo would have gathered around him a rag-tag crew from all the corners of the world. Of course, this whiteness was almost all-prevailing in Hollywood films at the time, but various other movies at least made the effort of including one or two black actors in the cast in order to hint at some multitude.

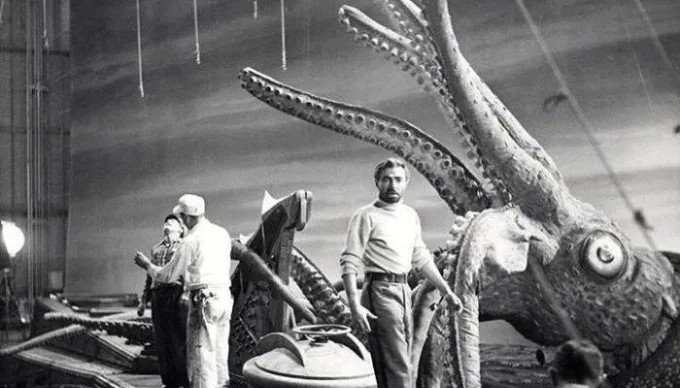

What people remember from the film, though, is the magnificent design of the Nautilus, and the battle with the squid. For a fifties movie, the special effects are mind-boggling, and hold up even today. The scene is a roller coaster ride. A great monster attacks the ship during a pitch-black night, ravaged by a fierce thunderstorm. The crew hacks away at the kraken with axes, knives and harpoons, with Nemo leading the charge. The squid tosses sailors off the submarine, gets hold of Nemo, and lifts him high in the air, its terrifying beak ready to devour him. At the last minute, Ned Land, having saved himself from near-drowning below deck, leaps into action, driving away the monster with a well-aimed harpoon throw, and rescues a lifeless Nemo from certain drowning by diving after him into the depths.

However, the scene initially was a complete disaster. This is how Richard Fleischer describes it to Joe Fordham at the Cinefex blog: ”The squid was the first thing that I photographed, although none of that is in the picture. Everybody that was involved made a terrible mistake because it was written to be shot on a calm sea at sunset, which meant we had no way to hide the cables. The first squid that we shot had almost no motion to it at all, and it was not really waterproof. The stunt men were wrestling the squid arms, pretending the squid was attacking them, although they were attacking the squid, and it was disintegrating. Chunks were falling off because it was filled with kapok and that was absorbing water, getting heavier and heavier, then the cables would snap. Walt Disney saw the dailies and said it looked like a Keystone Cops comedy. He got some of the animatronic geniuses at Disneyland to help out, and that is where special effects supervisor Robert A. Mattey came into the picture.” For the DVD release of the 50th anniversary edition of the film in 2004, Disney dug up the old footage and edited it with the help of storyboards, and the grand turkey, labelled ”sunset squid” is up on Youtube for everyone to see. Compare it to the final scene here.

Under the guidance of Mattey, the film team set about to completely re-design the squid to give it a lot more movement and durability. The new squid also partly relied on wire-work, but the wires got hidden by the darkness and the spray of water. But the monster prop was filled to the max with hydraulics and pneumatics to make the tentacles move and grab, and it had eyes that could open and close, as well as the animated beak. It is worth pointing out that no prop or puppet even remotely relatable to this had ever been built for a movie before. Any time a monster such as this appeared on screen, it would either be a stop-motion model, as in King Kong (1933, review), a man in a suit, like in Gojira (1954, review), a miniature marionette, like in Monster from the Ocean Floor, or live animals that were either matted in or were rear-projected to appear huge, as in Killers from Space (1954, review). Them! (1954, review) had used actual full-size ant puppets, but they weren’t nearly as advanced as the giant squid.

Robert Mattey pushed special effects another notch upwards with this movie. This was noted by the Academy, which rewarded Disney with an Oscar for best special effects. Unfortunately, for the first half of the fifties, the Academy chose not to award the special effects creators specifically, but the movie as a whole, in other words: the producer. Thus, none of the SFX creators on the movie received the award.

Mattey had a background in engineering, and had worked on the creation of rides and attractions at Disneyland. Mattey was the one in charge of bringing together a team for designing a working mechanical squid, and when it was all said and done, the behemoth required 34 people to operate it. In the end the creation of the squid scene cost Disney over one million dollars to make – and it takes up five minutes of screen time. To put this in comparison. One million dollars was the entire shooting budget for The Day the Earth Stood Still. And up until 1954 The War of the Worlds (1953, review), which cost 2 million dollars to make)]. This just goes to show how perceptive Walt Disney was of the importance of this one scene. This was the one scene that people would be talking about when they exited the movie theatres, the scene they would tell their friends about, the scene that the critics would pick apart. This was the scene that the movie would be remembered for. If it worked, people would forget about the clunky script and Kirk Douglas‘ awful song. If it didn’t work, he basically had the world’s most expensive B movie on his hands.

One of the trickiest bits of filming were the shots of the Nautilus ramming other ships, whether shot above or below sea level. These scenes were both shot on wet sets and on dry-for-wet sets, and incorporated a number of tricks, such as shooting upside-down. The effects team had difficulties devising a way to make their large models of the Nautilus travel realistically through the waters, and so enlisted the help of Republic Studio’s heads of special effects, brothers Theodore and Howard Lydecker, to help design one of their patented Lydecker rigs, which they had used primarily for shooting miniature airplanes, but worked perfectly for a submarine.

One of the problems the studio encountered was the fact that they only had one Cinemascope lens, which meant they couldn’t film special effects shots at the same time as principle photography was going on. With all the effects shots that needed to be done, Disney couldn’t afford to wait, so a solution had to be found. To understand the problem one must understand Cinemascope. A Cinemascope lens was basically a carefully designed wide-angle lens that compressed the image vertically, but not horizontally. By compressing the image, the lens was able to capture extremely wide landscapes onto standard film. Movie theatres were then outfitted with projection lenses that reversed this process, and stretched out the compressed images from the film frames. So the problem was that if the miniature scenes were filmed with a standard lens, the standard images would also be stretched out by the projection lenses at the movie theatres, making the Nautilus and its surroundings seem twice as long as they were in reality. Finally concept designer Harper Goff came up with a solution that was brilliant in its simplicity: if the image of reality couldn’t be squeezed with a normal lens, then the only solution was to squeeze reality itself. Thus, he ordered the model shop to create a model of the Nautilus that was twice as short as the real thing, but had the same height. This also meant that all the proportions had to be squeezed – making circles into ovals, and so on – even down to the rivets. When the image was stretched by the cinema projector, the stubby Nautilus would look just like the one filmed with Cinemascope. ”The air bubbles did look a bit strange, but no-one seemed to mind”, said Goff.

Another impressive feature of the film were the many matte paintings – whether the docks in San Francisco, underwater landscapes, slave islands, or numerous ocean horizons – they are all extremely naturalistic and beautiful. The mattes were painted by Oscar winner Peter Ellenshaw, a British artist who had worked on Alexander Korda’s and H.G. Wells science fiction epic Things to Come in Britain before moving to Hollywood in 1950 to start working with Disney’s first live-action film Treasure Island. In an interview with Cinefex Ellenshaw claims that Disney was basically working with antiquated methods, and he more or less had to bring them up to the fifties by himself. However, most of the time on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was spent with the miniature department, as Ralph Hammeras wasn’t quite up to speed on how to light the Nautilus and other miniatures to make them look realistic. With his artistic eye for light, Ellenshaw had to assist the miniature team for such lengths that he often didn’t have time to prepare his mattes for the principle photography crew, which meant he had to take his glass panes and paint the mattes on location.

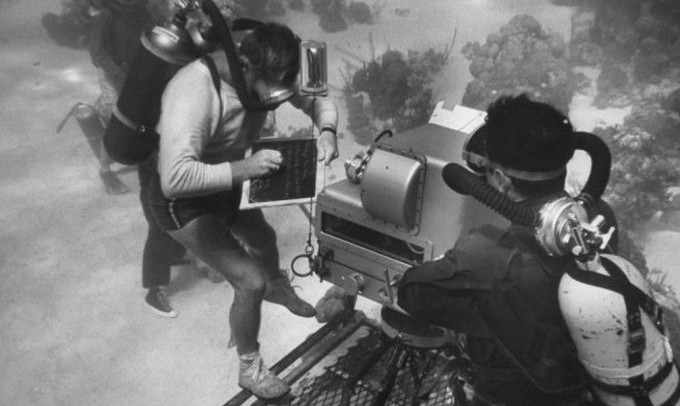

As most of the film takes place on or in the ocean, underwater photography was crucial. Disney purpose-built a giant water tank at its studio for both live-action and miniature photography, but the principal photography crew also spent a lot of time filming in the Bahamas, on the same spot as the 1916 adaptation of the same book was made, and in Jamaica, particularly for the scene with the attacking natives. So big was the production that at one time a crew of 400 people were involved in shooting underwater scenes. Disney gathered together the cream of the crop of people with experience of underwater photography, one of the stunt divers involved was a celebrity, even though no-one knew his name at the time, in fact it was the Gill-man from Creature from the Black Lagoon, Ricou Browning.

The film opened to rave reviews around the world, even the notoriously science fiction-hostile New York Times’ reviewer Bosley Crowther gave it high marks. Crowther even gave his blessing to the idea of making the Nautilus nuclear-powered, calling it ”wholly within the vein of wild imagination and fabrication, that flows through this vivid, crazy film.” Although Crowther did bemoan the that there was, in his opinion, too little exotic marine life in the movie. The movie made back its budget, grossing 8 million dollars in the US in the opening year, and has since racked in 25 million dollars for Disney.

Later reviewers have called upon the opposite, claiming that too much time is spent gawking at the wonders of the deep, which bogs the movie down. Indeed, the most common criticism of the movie from modern critics is that the film is too slow-moving and too long, at 128 minutes. In general, time has perhaps elevated the film to slightly too high a pedestal, as many modern reviewers are awe-struck by the fact that the film’s special effects hold up even to this day, and forget to mention that the script is something of a mess, and the film is constantly in danger of falling into ridicule by Kirk Douglas’ scene-stealing and hamming. But to be honest, it never does tilt all the way over, but keeps its balance between dark seriousness and light clownery. And Douglas IS entertaining, there’s no way around it.

One frequent criticism is a scene where Ned Land gets put off by Nemo’s offerings of sea-food. Sure, sauté of unborn octopus and ”milk” from sperm whale would make most modern diners a bit queasy, but it’s difficult to imagine a seasoned sailor like Land turning his nose up at sea cucumber and snake, declaring all the sea-food ”unfit for eating”.

Of course, Jules Verne has long since become the property of the world (and Verne was indeed a model of internationalism), but I still thought it would be interesting to see what French critics thought of the adaptation of their national treasure. And indeed, France’s leading science fiction publication Cinemafantastique does point out that the plot is ”freely drawn” from the book, and simplified for a juvenile audience, but still gives the film 4/5 stars and calls it ”the best adaptation” of the book. Devildead gives the film a glowing review, calling it a ”non-stop series of stunning adventures”, and praises the special effects and the ”majestic design” of the Nautilus. According to the website, the film ”stubbornly refuses to age”.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is certainly a bit slow, perhaps over-long and feels as it jumps from one big event to another. For example, the fifteen minutes of film incorporating Ned Land trying to escape on an island, just to get chased back to the submarine by blood-thirsty natives could well have been cut out without the film suffering one tiny bit from it. The scriptwriters could easily have devised of another reason for Nemo to lock Land below deck, if they thought that was necessary. But despite its flaws, the movie is an exhilarating adventure movie that doesn’t shy away from the original’s dark themes. James Mason is without doubt the best Nemo ever to grace the screen, all apologies to Michael Caine. Visually, the movie is pure eye-candy and the squid scene is – although it has been repeated ad infinitum – a landmark in special effects. It caters to both a juvenile and an adult audience in a way that few films manage, and still holds up as one of the great Disney adventure movies.

There are many misconceptions about Jules Verne, particularly in English-speaking countries, which mainly stem from the terrible early English translations, that are now unfortunately in the public domain, and therefore the basis of many cheap book reprints. The early English translations were riddled with errors and Verne’s English translators would often cut out huge chunks of political and philosophical content that didn’t fit their world-view. I recommend this post by Ron Miller for further reading on the misconceptions about the author. English translations, for example, stated the the propellers of the Nautilus rotated at 120 rotations per second, when Verne wrote per minute, and gave a detailed description how the Nautilus floated because “iron is lighter than water”.

The main thing to remember about Jules Verne’s famous novels is that they were published under the umbrella title ”Fantastic Voyages”. What Verne set out to do was to bring the reader on a voyage around the world, from the sun and the moon to the depths of the Earth and the bottom of the sea. He wanted us to visit all the continents, as many countries as possible, see all the cultures, meet the people, explore the poles, the vast deserts and the deepest jungles. The science fiction elements often came into play at times when Verne had to devise of a way to get the reader to these places. To see the moon you had to get there first. The visit the bottom of the ocean, you had to have a submarine. Verne himself protested the notion that he invented new technology. According to him, he took scientific theories and existing technology and elaborated. For example, he didn’t invent the submarine. There had been several experimental submarines made in the 19th century, many of them in France, and in 1864, five years prior to the publication of the first chapter of Verne’s book, a Confederate submarine sunk a Union sloop in the American Civil War. The Nautilus was powered by a souped-up version of 19th century batteries, Verne even states the brand: Bunsen batteries, by the company that also manufactured the Bunsen burner. Even Verne’s rocket to the moon was based on available technology. That Verne’s applications of said existing technologies didn’t always match up to what was possible in reality is another issue. And sometimes he used far-fetched ideas that he didn’t even believe were true, such as the hollow Earth idea in Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

In the early days of cinema, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was a common subject. There were plans for an American big-budget movie 1905, but they seem to have fallen through, and in 1907 George Méliès made a film loosely based on the book. 1916 saw the first feature film based on the book, and in 1927-1929 the ambitious but messy part-talkie-part-silent movie The Mysterious Island (review) freely adapted several concepts from the book into the story. In 1975 there was a Soviet adaption called Captain Nemo, and there have been several films featuring concepts and characters from the book made both for TV and the big screen. Some will remember Omar Sharif as Captain Nemo from the 1973 film The Mysterious Island, and the best known TV adaptation of the book is probably the 1997 TV movie starring Michael Caine in the pivotal role. Modern viewers will be familiar with the rather disappointing The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), adapted from the Alan Moore comic book by the same name, which to a large extent takes place upon the Nautilus, and is one of the few films where Nemo’s ”Eastern” descent is put front an centre, as he is portrayed by Indian actor Naseeruddin Shah.

Interestingly enough, no cinematic Hollywood adaptation of the book has been made since 1954, and it wasn’t until 2009 that there were serious discussions about doing a new movie. That year Disney announced a remake was in the works, with action director McG as director, and he wanted Will Smith to play Nemo. Smith declined and McG was also quickly out of the picture. David Fincher then got attached to the project, and developed it for over five years, Brad Pitt poised for the role of Ned Land. However, Pitt then withdrew and the project stalled — according to Fincher because of casting problems. James Mangold was brought in to direct in 2016, and in 2019 Disney confirmed that the project was still going ahead. Little has been heard of it since, though. Also in 2016 Fox announced another adaptation of the book, helmed by Bryan Singer. However, with Disney’s acquisition of Fox in 2019, that project was swiftly buried. In 2015, Christophe Gans brought the news that he was going to direct a third version, this one in a Chinese setting, undoubtedly wanting to tap in to the huge Chinese market. That, also, seems to have gone nowhere. With that, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea joins the long line of SF novels and remakes stuck in Hollywood development hell, which is unfortunately a result of the bloated budgets of movies these days.

British thespian turned movie star James Mason was voted Britain’s greatest film star three years in a row in the late forties. In 1946 the Brits thought, ”to Hell with it”, and decided to name him the greatest international star as well. One can’t list all the great films he’s been in, but such as should at least be mentioned are Julius Caesar (1953), A Star is Born (1954), for which he was nominated for an Oscar and won a Golden Globe, Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1962), Anthony Mann’s The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) and Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict (1982), for which he received his third Oscar nomination. Friends of horror know him from leading roles in Child’s Play (1972) and Salem’s Lot (1979). His only other science fiction outing was yet another leading role in yet another classy Jules Verne adaptation, 20th Century Fox’ Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959).

It is easy to imagine that James Mason felt a kind of kinship with the pacifist Nemo, shunned by the world. Mason refused to bear arms during WWII, causing parts of his family to break with him for many years to come. Mason was also a great lover of animals, especially cats, and in 1959 he co-wrote a book about the cats in his life along with his wife.

Kirk Douglas was also nominated for Oscars three times, and won an honorary lifetime achievement Oscar in 1996. Impeccably prepared for every role he took on, and later a major player in Hollywood as a producer, Douglas tended to favour entertainment over message-heavy movies. He worked in all conceivable genres, tilted towards adventure and comedy, but was just as beloved as western hero, WWII soldier and romantic lead. But he also thrived in demanding dramatic roles, like his portrayal of Vincent van Gogh in Lust for Life (1956), earning him his third Oscar nomination. He didn’t shy away from science fiction either, appearing in a minor role in the forgotten Rock Hudson gem Seconds (1966), playing the title roles in a strange musical TV version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1973) and playing the lead in Saturn 3 (1980) and The Final Countdown (1980). A testament to Douglas’ longevity is that in these last named films he played romantic action hero leads that were written for actors 30 or 35 years younger than him – he was 63 when they were filmed. And a testament to the love of his craft was that he continued to act even after his crippling stroke in 1996 – he played his (hitherto) final role in 2008, at the age of 92. Douglas passed away in February, 2020, at the respectable age of 103.

Paul Lukas was of Hungarian descent, although a Hollywood veteran and a naturalised citizen of USA. He won an Oscar in the thirties and was a highly respected character actor, who had been a prominent leading man in the thirties. His role in the movie is rather bland, overwhelmed as he is by his three co-stars. At 63 he also suffered from memory loss on the movie, which makes some of his lines very stilted, as he either concentrates on remembering what he’s supposed to say, or looks like he’s reading from a cue card. His trouble remembering lines also reportedly made him grumpy and difficult to work with.

Of Austro-Hungarian descent, born to German-speaking parents in what was then the Hungarian part of the country, but today a part of Slovakia, Peter Lorre made his bones in German stage and film, and his career would forever be informed by his role as a persecuted child-murderer in Fritz Lang’s expressionistic masterpiece M (1931), although mainstream audiences may know him better from his weaselly performances alongside Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Casablanca (1942). His career hit a slump in the late forties, a slump he was never quite able to get himself out of. Although constantly working up until his death in 1964, good roles were few and far between, and from the fifties onward he worked more in TV than in films.

We have seen him before on the blog, in the European co-production F.P.1. Does Not Answer (1932, review), and he played a memorable villain in Mad Love (1935), considered by some a sci-fi film, but I call it supernatural horror (a great film nonetheless). He also appeared in Invisible Agent (1942, review), as a Japanese villain. He would go on to appear in three more sci-fi epics, The Story of Mankind (1957), Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961) and another Verne adaptation, Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962, although it is questionable whether that can be called sci-fi).

Robert Mattey worked with special effects in a number of films in the sixties and seventies. He was nominated for an Oscar for The Absent Minded Professor (1961), but is probably better known for creating the effects for Mary Poppins and for building the mechanical shark for Jaws (1975) and Jaws 2 (1978). Chris Mueller was in charge of sculpting the model of the squid. He was one of the main sculptor at Disney, where he created many of the characters and decorations for Disneyland. He was in charge of sculpting the full-size bust of the Gill-man’s head for Creature From the Black Lagoon, sculpted the mutant for This Island Earth (1955, review), and the shark for Jaws. Joshua Meador was an animator, and probably created some of the subtle animation in the movie such as fish swimming past the camera, and the less subtle, as the electric arcs that the Nautilus uses to scare away the attacking natives. Meador was leased out from Disney to MGM in 1956 to create the animated monster in Forbidden Planet (1956, review).

Of course, the squid wasn’t the only special effect in the film, which contained a number of miniature shots, both above and below water, explosions, an intricate iris shutter for the Nautilus underwater observation window, storms, rain and waves, and a great scene depicting the flooding of the Nautilus. Numerous models and miniatures were built, both of the Nautilus and other ships, as well as the squid, the volcano base and other surroundings and buildings. Disney legend Ub Iwerks was on hand to do the fickle processes of combining mattes, animations and live action shots. Process photography was done by another old-time legend, Ralph Hammeras, who had worked on the original giant monster movie The Lost World (1925, review), as well as Just Imagine (1930). He went on on to work on three other sci-fis with rather lower status: The Black Scorpion (1957 review), The Giant Claw (1957, review) and The Giant Gila Monster (1959). Another legend on board was Marcel Delgado, the man who always stood in the shadow of stop-motion animator Willis O’Brien. Although O’Brien animated, it was Marcel Delgado who created the puppets for The Lost World and King Kong. He also worked on The Wizard of Oz (1939), Mighty Joe Young (1949), The War of the Worlds, Mary Poppins and Fantastic Voyage (1966), to name a few. Special effects supervisor for the miniature unit was Fred Sersen, a man who was nominated for Oscars eight times and won twice. He also worked on The Day the Earth Stood Still. This team may well be the most impressive special effects roster brought together on a single science fiction film until Stanley Kubrick came along with 2001: A Spade Odyssey (1968).

Peter Ellenshaw also did mattes for The Absent Minded Professor, Son of Flubber (1963), The Island at the Top of the World (1974), The Black Hole (1979), for which he was nominated for a Saturn Award, and Superman IV: The Quest for Peace, as well as Spartacus (1960), Mary Poppins, The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Quo Vadis (1951), In Search of the Castaways (1962), and many more high-profile films.

The stunt team consisted of many of Hollywood’s greatest stuntmen, including one who’s gone on to some cult fame: Gil Perkins, who donned the Frankenstein makeup as Bela Lugosi’s double in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943, review) and played the monster in House of Frankenstein (1944, review). Stunt coordinator for the film was Carey Loftin, perhaps because Disney mistook him for one of Hollywood’s greatest stunt divers, when he was in fact one of Hollywood’s greatest stunt drivers. Another legend on the stunt team was Jack Williams, who continued to work as a stuntman all the way up until 1999 and Wild Wild West. And there was a man brilliantly named George Robotham.

The music of the film does what music is supposed to do in a movie, sets the tone, highlights the action and carries the scenes. Composer was Disney’s in-house man Paul J. Smith, who won an Oscar for his score in Pinocchio (1940). His music works without being especially memorable. Cinematographer Franz Planer was of Austro-Hungarian descent, and worked on another film on this blog, Henrik Galeen’s Alraune (1928, review) starring German superstar Brigitte Helm. The lighting of the movie, especially in the scenes inside the Nautilus, is sublime, but apart from that the cinematography is good, but traditional, as one would expect from a seasoned veteran like Planer.

Makeup supervisor was Swedish Gustaf Norin, who worked on the TV series The Adventures of Superman and My Favourite Martian, as well as the sci-fi movie Willard (1971). Sound director C.O. Slyfield was nominated for four Oscars for his work on Disney animations, and received a Special Technical Achievement Oscar for developing a device for locating noise in sound tracks.

Among the supporting cast one may notice Robert J. Wilke in a prominent (and very well played) role as the tough first mate on the Nautilus. Wilke was a veteran of sci-fi serials, and also appeared in Tarantula (1955, review) and The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler (1971). There are bit-parts by a few people showing up in sci-fi films. Chet Brandenburg was in The Invisible Man Returns (1940, review), The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942, review), The Day the Earth Stood Still, The War of the Worlds (1953), Indestructible Man (1956, review), The Vampire (1957, review), The Deadly Mantis (1957, review), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review) and Son of Flubber (1963). Fred Graham appeared in The War of the Worlds, The Giant Gila Monster (1959) and The Killer Shrews (1959).

As a young drummer boy we see Charles Grodin, who rose to fame with his Golden Globe-nominated performance in The Heartbreak Kid (1972) and is perhaps best known as the dad in the comedies Beethoven (1992) and Beethoven’s 2nd (1993). He also played the lead in The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981). Charles Morton appeared in The Invisible Man (1933, review), Captive Wild Woman (1943, review), The War of the Worlds, The Night the World Exploded (1957, review), Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961). In the role of a sailor we see a man called Sailor Vincent (if ever nomen was omen), who also appeared in the Spencer Tracy version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941, review), Tarantula and The Land Unknown (1957, review).

Janne Wass

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. 1954, USA. Directed by Richard Fleischer. Written by Earl Felton. Based on the novel with the same name by Jules Verne. Starring: Kirk Douglas, James Mason, Paul Lukas, Peter Lorre, Robert J. Wilke, Ted de Corsia, Carleton Young, J.M. Kerrigan, Percy Helton, Ted Cooper, Charles Grodin. Music: Paul. J. Smith. Cinematography: Franz Planer. Editing: Elmo Williams. Production design: Harper Goff. Art direction: John Meehan. Set decoration: Emile Kuri. Makeup supervisor: Gustaf Norin. Sound director: C.O. Slyfield. Special effects director: Robert A. Mattey. Visual effects supervisor: Fred Sersen. Stunt coordinator: Carey Loftin. Wardrobe supervisor: Robert Martien. Produced by Walt Disney for Walt Disney Productions.

Leave a comment