A 1956 cult classic, this gangster-monster mashup with Lon Chaney Jr. as a super-charged avenger suffers from the cutting of most of Chaney’s lines, and with them key scenes. Decent performances & good location shooting make it worth a watch. 3/10

Indestructible Man. 1956, USA. Directed by Jack Pollexfen. Written by Jack Pollexfen, Sue Dwiggins, Vy Russell. Starring: Lon Chaney, Jr., Max Showalter, Marian Carr, Ross Elliott, Robert Shayne. Produced by Jack Pollexfen. IMDb: 4.3/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Having just come off my review of the pioneering SF classic Forbidden Planet (1956, review) and turning to Indestructible Man feels like being snapped back nearly two decades with a rubber band, even though the two movies were released only weeks apart. Where MGM’s Forbidden Planet, with its sleekly designed, pastel hued alien world, pointed toward the future of science fiction movies, Allied Artists’ Indestructible Man mined their past. A throwback to the mad scientist films and gangster movies of the early forties, it featured Lon Chaney, Jr., a washed-up remnant from the Universal monster movies’ second coming, a mad scientist in the Lionel Atwill mold and villains with named like “Butcher” and “Squeamy”.

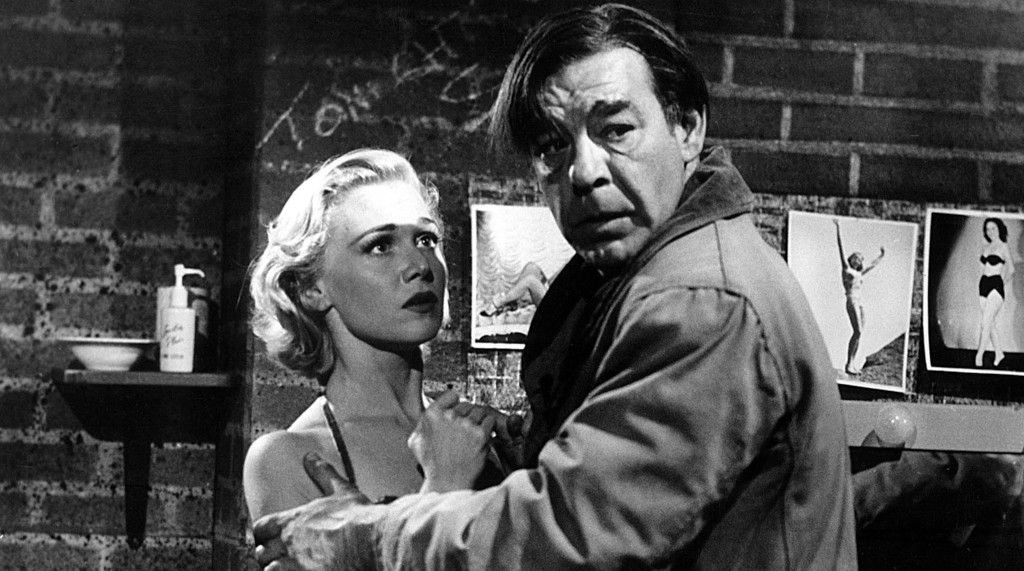

Set on the US west coast, the film follows, on the one hand, a career criminal by the name of Charles “Butcher” Benton (Lon Chaney, Jr.), and on the other hand police officer Dick “Dick” Chasen (Max Showalter), who is trying to catch him. The movie opens with Butcher behind bars in San Francisco, about to be sentenced to death for a 600,000 dollar robbery. Apparently, the heist was planned by a group of four criminals in Los Angeles, including Butcher, Squeamy (Marvin Press), Joe (Ken Terrell) and their underworld lawyer Paul Lowe (Ross Elliott). But Butcher got greedy and hid the money for himself somewhere in the city. As Butcher got greedy, his accomplices squealed and turned him in. On death row, Butcher swears he will get his revenge on the three, dead or alive, before being led to the gas chamber.

In a basement laboratory, well-meaning mad scientist Professor Bradshaw (Robert Shayne) and his assistant (Joe Flynn from McHale’s Navy) are doing research into a miraculous cancer cure involving high-voltage electrical shocks. They “purchase” Butcher’s dead body from the morgue, and send nearly 300,000 volts through it. Whether or not this is a suitable cure for cancer we never get to know, but at least it seems to do the trick if you want to revive someone who has been put to death in the gas chamber. Not only this; because Butcher’s cells have multiplied infinitesimally due to the treatment, his density is so high he is all but indestructible, and has the strength of a grizzly bear to boot. The only problem is that the electricity has fried his vocal cords (very conveniently the only things it has fried), turning him mute. When he learns of his new enhancements, Butcher kills his two saviours and heads out to L.A. to execute his revenge — on the way killing two police officers, setting the Los Angeles police on high alert that a cop killer is headed their way. Enter Lt. Dick Chasen, the officer who has been working on the 600,000 dollar robbery Butcher and his accomplices have pulled off. Now that Butcher is dead and the money still missing, Dick clears Butcher’s former girlfriend-not-girlfriend Eva (Marian Carr), a burlesque dancer who is now seeing-not-seeing the lawyer Paul Lowe. Nevertheless, Dick asks Eva out on a date, and we have our romantic couple of the film.

The film now follows two plot strands parallel to each other. The first follows the Butcher trying to locate and kill the people who turned him in. Director Jack Pollexfen shoots a tattered and sweaty Chaney walking mute around Los Angeles, communicating through close-ups of his twitchy, watery eyes and an assortment of facial expressions that are often somewhat difficult to interpret. The other one follows the LAPD slowly realising that the indestructible cop killer is in fact the Butcher come back to life, but trailing one step behind the bodies that drop (sometimes literally, from a great height). The two strands come together as the police finally learn that the Butcher has hid the money in the Los Angeles sewer system, and catch up with him there. Bringing out the heavy artillery, the police hit the Butcher with a bazooka round to the stomach and dowse him with a flame thrower. Scarred and weakened, he climbs out of the sewers and finds himself at an electrical plant. With Dick Chasen and the police on his tale, he climbs a machine and drives it — deliberately — into a high-voltage wire — thus ending his own miserable existence.

The movie has a sort of semi-documentary feel, as it is narrated all the way through by Showalter, in the hard-boiled but precise style popularised by the TV show Dragnet (1951-1959).

Indestructible Man is one of the low-budget monster movies of the fifties that receives more love than its meagre budget and quality would suggest, partly, I suspect, because it was one that ran frequently as a weekend matinee on TV back in the day. Another reason, of course, is that it stars Lon Chaney, Jr. And there’s got to be something special to it, as film historian Tom Weaver has devoted an entire book to the picture. I must admit that I have never been a fan. Over the years, I have tried to watch it three times, and I am not exaggerating when saying that I have fallen asleep halfway through all three times (last time I actually made it to the 60-minute mark of the 70-minute movie). But rather than nitpicking its faults, in this post I will try to understand why the movie has such a strong following.

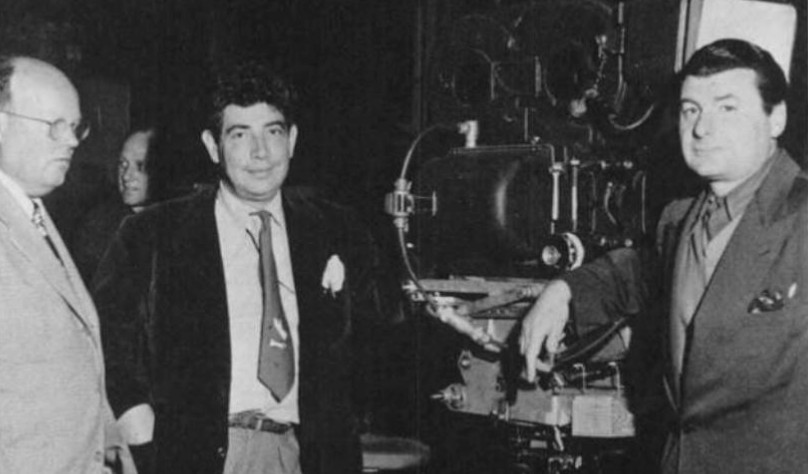

It all starts with Jack Pollexfen, a name that may be obscure even to the more devout friends of fifties horror and SF. A journalist, “off-off-Broadway” playwright and later screenwriter, producer and occasional director, Pollexfen started rattling around the lower tiers of Hollywood as a screenwriter for hire, “pure assembly-line junk” he called his first scripts, in the late forties. He found a writing partner in British expat Aubrey Wisberg, and together they had a massive surprise hit as writers and producers of the moody low-budget SF horror film The Man from Planet X (review) in 1951. Cleverly and atmospherically directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, it looked at least three times more expensive than its actual budget of just 40,000 dollars. Between 1951 and 1955 the duo wrote and produced around a dozen films, sometimes lending their talents to other producers, together or apart. During these years they cranked out a steady stream of interesting but bad, although seldom bottom-of-the-barrel-terrible, low-budget movies. Many of their films were “creative” re-workings of classic adventure novels and stories, such as Lady in the Iron Mask (1952), Captain John Smith and Pocahontas (1953) or Return to Treasure Island (1954). Almost invariably these were low-budget productions made for a small company and then sold on to a distributor like RKO, Allied Artists or Twentieth Century-Fox as B-movies. Eventually these eye-catching reworkings caught the eye of RKO, and the duo finally had the chance to write a script for a million dollar movie, Son of Sinbad (1955). In between Pollexfen had a minor hit writing on his own for Columbia; the result was The Son of Dr. Jekyll (1951, review), and together he and Wisberg wrote and produced the SF movies Captive Women (1952, review), Port Sinister (1953, review) and The Neanderthal Man (1953, review). Best known of these, and something of a cult classic, is The Neanderthal Man, which has a small league of devout fans. Most interesting is Captive Women, a mis-titled obscurity originally titled “3000 AD”, a sort of precursor to the Mad Max films, set in a post-atomic New York, with Medieval-ish tribes scheming for power.

Captive Women is a prime example of a Pollexfen-Wisberg production inasmuch as it is a grand story that a major studio wouldn’t touch without a million dollar budget, but turned out on little more than pocket money, sometimes to startlingly effective results. As Tom Weaver puts it in his book Indestructible Man, “the concepts were as high as the budgets were low”. The Wisberg-Pollexfen productions never looked expensive, but that they were able to get on screen what they did with the money they had tells of an unusually clever production collaboration. In an interview with Weaver, Pollexfen credits much of this to the fact that he would often collaborate with really talented directors like Edgar Ulmer or E.A. Dupont — directors that had a reputation of being “difficult” and therefore were shunned by major studios, and would therefore work cheap. But there’s also another Pollexfen-Wisberg trademark that is, unfortunately, prominent in Captive Women: the fact that their scripts often start out with very interesting ideas that aren’t carried through to the end of the film.

Jack Pollexfen has directorial and producer credits on Indestructible Man, but no writing credit. The script is credited to Vy Russell and Sue Dwiggins. However, Pollexfen tells Weaver that he did the story draft for the movie, but didn’t want producer-director-writer credits, “I thought I should leave such credits to Chaplin and Welles“. Russell and Dwiggins, then named Sue Bradford, says Pollexfen, were wives of Bill Bradford and Jack Russell, two of the cameramen often enlisted by Pollexfen and Wisberg, “they helped me on the second draft”. In fact, both were screenwriters, primarily for TV, and had been part of the Pollexfen-Wisberg team as production assistants and all-round helpers since the beginning. Sue Dwiggins went on to a a long career in the production coordination department and production services up until the 90’s. That Pollexfen ended up directing Indestructible Man was not by choice, he tells Weaver that none of his usual directors were available, he had done some directing in the past and had his director’s guild membership, so he decided to take on the responsibility.

While best known for his horror output, Lon Chaney, Jr. was an extremely busy actor in the early 50’s, often playing heavies and, for some reason, Native Americans, in film and on TV in almost all conceivable genres. His star had diminished considerably since his heyday as Universal’s top monster in the early forties, but he was still turning out memorable supporting roles in A-grade films, primarily westerns like Springfield Rifle (1952), The Indian Fighter (1955), and not least in the classic High Noon (1952), as well as the occasional drama like Not a Stranger, opposite stars like Olivia de Havilland, Robert Mitchum and Frank Sinatra or comedies like the Martin-Lewis vehicle Pardners (1956) and alongside Bob Hope in Casanova’s Big Night Out (1954). So while not the major star he once was, Lon Chaney, Jr. still had som marquee draw left in him, even if Indestructible Man was the first time he was first-billed since 1948. And as his involvement in Indestructible Man and other less-than-prestige pictures prove, he didn’t quite have the luxury to choose his projects. Chaney came a long way on his 6’2 stature and beefy build, combined with an intense stare and a mean scowl, often seeming as to hide a sense of vulnerability — a combination which made his turns as tragic monster in the Universal pictures so successful, and one that had first drawn attention in his break-through role as Lennie in Of Mice and Men (1939). But by the 50’s he also had a reputation as a heavy drinker and an actor that was difficult to work with. However, while he himself made no secret of his drinking — he warned Pollexfen never to change the script after lunch, as he would take it in liquid form — this reputation is probably somewhat overblown, considering the sheer number of films and TV productions that Chaney racked up in the fifties. It has often been suggested that his role was changed into a mute in Indestructible Man because Chaney was too drunk to remember his lines, but Pollexfen dismisses this: “Chaney could handle dialogue reasonably well [before lunch]. Of course, a talkative monster would tend to be ridiculous. I found him intelligent, probably more so than most actors.”

If Pollexfen was good at choosing his directors, he also made sure to employ competent cinematographers whom he could trust and who understood what he wanted. One such was the afore-mentioned John Russell, a workhorse who had been around since the early days of the talkies, primarily working freelance in low-budget movies and later extensively in TV. His reliable work on Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1962) prompted Hitchcock himself to choose him as DP for Psycho (1960),one of his few A-grade movies, which made him responsible for some of the most iconic shots in cinema history and an Oscar nomination to boot (the win went to Freddie Francis for the D.H. Lawrence adaptation Sons and Lovers, which racked up seven Academy Award nominations, but which has since fallen pretty much in obscurity). His collaboration with Hitchcock resumed with The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1962-1965). In Indestructible Man, Pollexfen and Russell alternate between German expressionism in scenes involving the mad scientist, the noirish look of Warner’s gangster movies and sometimes even move into cinema vérité territory, with stark, naked scenes of the streets of Los Angeles, reminding me of William Friedkin’s work in films like The French Connection (1971). Not that Pollexfen is a Friedkin, but there are a number of very stylish sequences in the movie. A standouts is the one centred on the Angels Flights funicular and the parallel Third Street Stairs, with Eva riding down the funicular escaping the Butcher, and seeing one of her old friends whom the Butcher is after running up the stairs on crutches. These were filmed in normal traffic, and if you look closely, you can see pedestrians stopping and trying to talk to Chaney.

As was often the case on Pollexfen’s movies, the ending of Indestructible Man is somewhat abrupt and flat. The Butcher never gets his revenge on Lowe, who is never seen again after the scene where he tells the police where to find the loot. Also, we never get the showdown we anticipate between Butcher and Dick over the hand of Eva — it is customary in these films for the monster to rob away the princess at some point, but this never happens. According to Weaver, these things did happen in the original script. Up to page 70, the film follows the script, that is, more or less up to the point that Lowe gives the police the information on where the loot is buried. But then things diverge. In the script, Butcher goes to find his loot in a sump pit, and stashes it in a cave. As the film was written, the Butcher then gets his “hero” moment as he breaks into the police station, bends open the bars to Hume’s cell, and kills Hume. Butcher then scoops up Eva and takes her to his cave, where he is ambushed by the police, wielding bazookas and flame throwers. As the original script has it, the Butcher didn’t just happen on the electricity plant, but was lured there by Dick in a car chase, using Eva as bait. In the script, Chasen ultimately lures the Butcher to his death by electrocution. But during filming something happened, which seems to have derailed the shooting. First of all, the cave is discarded for the Los Angeles sewers, second, the whole plotline where Butcher gets his revenge on Lowe and kidnaps Eva is omitted and, likewise, the car chase, which also involved Eva. Instead of luring Butcher to the power plant, Chasen chases him there.

Weaver writes that something seems to have gone wrong during filming, but by the time he realised it, Pollexfen’s “memory was failing”, neither did Sue Dwiggins or Vy Russell remember exactly what happened. Weaver also interviewed Max Showalter, but that was before he realised that the ending was all “wrong”. Dwiggins tells Weaver she does remember that financing fell apart halfway through, but has no other recollections. That nobody interviewed mention that they would have returned for pick-up shooting would point to the fact that the film was more or less finished the first time around, and not, as some have speculated, shot piece-meal over a longer period, or picked up later.

One interesting thing to note is that after Butcher has emerged at the power plant, he is never again seen in a shot with any other actor. Eva is not present at the power plant in the film, although at the film’s ending, back at the police station, there’s a curious mention of her being “out of the hospital”, harking back to the unseen scene of her being kidnapped, suggesting that scene was filmed at some point, but later cut. All we get of Chasen and the police at the power plant are a few short, wordless insert shots. Apart from the occasional exclamation, the whole of the finale doesn’t contain a single piece of dialogue. It feels as the entire finale, which is surprisingly short and abrupt, is cut down and reassembled from a considerably longer sequence. According to Weaver, most, if not all, of what was written in the script was in fact shot, but for some reason discarded. The key scene where Butcher kills Lowe was filmed. There are production stills showing Chaney on the prison set, and several people interviewed by Weaver remember it being filmed. Both Vy Russell and Sue Dwiggins remember that the cave scene was shot in the famous Bronson Canyon, where so many Hollywood movies have been staged. Some of this footage is actually in the movie, intercut with the sewer scenes. Weaver also notes that in several places, scenes have changed places, for example the two murders are out of order, creating a number of continuity gaffes, and in many instances lines have been cut and replaced with Showalter’s narration. Sue Dwiggins also tells Weaver that the reason Eva changes shoes in the film, from high heels to a pair of flat bottoms, is that actress Marian Carr accidentally wore flat bottoms when climbing a gantry at the power station, so they had to do a scene where she changes shoes to avoid continuity errors. This means that they did also film the final scene with Eva at the power station. Plus, and this is, I think, crucial: in the original script, Butcher wasn’t actually mute, but gradually regained his voice.

The changes done to the film seem inexplicable, as Pollexfen has omitted several of the key scenes of the movie without any obvious reason. There is one explanation, though, that I am willing to put my money on. If, indeed, Pollexfen decided during editing that he wanted Chaney’s character to be mute, then he would have had to hack away all the scenes in which Chaney had any extensive dialogue, such as — well, the omitted scenes: we know from the script he had dialogue in the scene where he kills Lowe, we know he had dialogue in the cave scenes, and we know he had dialogue in the power plant scene. All of these are either completely omitted or shortened to bare minimum. And as Butcher slowly regained his ability to talk, this would explain why the beginning of the movie is more or less intact, while the cuts have almost all been made toward the end. Then why did Pollexfen not mention this to Weaver? My guess: he probably didn’t want to badmouth Chaney, or admit he had done to Chaney what Universal did to Bela Lugosi in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man. Of all the explanations possible, it feels this is the only one that really sits.

What is remarkable is that despite these major last-minute editing changes, almost completely omitting three of the final major scenes, the film still works surprisingly well. Despite the continuity errors and the omitted scenes, the film’s plot is, on the whole, solid. The acting is as good as you’d suspect in a low-budget clunker of this kind, that is to say, uneven but overall passable. Max Showalter, best known for lighter, comedic fare, is perhaps somewhat miscast in the role as the Dragnet-type detective, but I’d say this is to the film’s advantage, as Showalter brings some lightness and charm to what might otherwise have been a rather dreary affair. Lon Chaney is Lon Chaney, and his brutish charisma dominates the movie, and no matter how irritated you may get at the constant inserts of his squinting eyes in lieu of actual lines, he very adequately portrays someone you would not want to meet in a dark alley, supercharged or not. Paul Lowe, Ken Terrell and Marvin Press all do their gangster bit parts with gusto, Terrell’s hopping around on crutches adding a meaningless but interesting quality to the character. Mustachioed Robert Shayne, a staple in fifties SF movies, does a good Lionel Atwill impersonation as the mad scientist, and one would have liked to have seen more of the uncredited Joe Flynn as his sympathetic assistant. Marian Carr is completely miscast as a burlesque dancer — it is impossible to imagine this prim lady twirling nipple tassels in front of an audience. She also comes off badly in the acting department in this film, looking quite nervous and insecure in her role — which may be due to a lack of direction from Pollexfen.

As stated, the cinematography is is not at fault in this film, in fact it has its shining moments, and the movie benefits enormously from being shot almost entirely on location. Apart from the Angels Flight, another landmark in the movie is the Bradbury Building with its “extraordinary skylit atrium of access walkways, stairs and elevators, and their ornate ironwork”, which is best known for appearing as the home of toy maker J.F. Sebastian in Blade Runner (1982), and the setting for the climactic rooftop fight between Harrison Ford and Rutger Hauer. Indestructible Man is sometimes quoted as “one of the first” films to use the building, but this is not quite true. It had been used at least as far back as the early forties, very notably in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), and in at least a half dozen other movies. The movie also benefits, sort of, from Albert Glasser’s bombastic score. According to Weaver’s book, it’s unclear whether Glasser wrote new music or re-used old pieces for the film. Glasser did not get a composer credit for the film, he does not mention it in his autobiography and there are no preserved records of either an original score or of how he might have put it together. However, that it is Glasser’s music in the film has been confirmed. It is certainly not his best score, and tends to overpowering at many points, but that is Glasser’s style. And at least it fits the story and adds powerful emotional cues.

But the film is not without its problems. While the continuity errors, the omitted scenes and the jumbled editing don’t ruin the movie, at least they drag the quality down, making it seem more rushed and ill-produced than it actually was. But there are also more fundamental problems. The movie tries to find a balance between a noirish police/gangster drama and an old-fashioned monster movie. In omitting two or three key scenes, the monster movie angle falls flat. In removing Chaney’s lines, Pollexfen robs the audience of Butcher’s character journey — the revenge on his nemesis, Lowe, the cave scene where Eva rejects his longing for love and his ultimate betrayal, as she is willing to act as bait in luring him to his doom. The film, thus, has to lean more heavily on the gangster/police plot, which was only ever intended as a framing device, and holds little of interest. There’s also a basic problem in the way the Butcher character is set up. This is the kind of role that Boris Karloff did a dozen of in the late thirties and early forties, a tragic anti-hero/villain wrongfully accused/set up and/or betrayed, who returns to exact his vengeance/justice. But it is incredibly difficult to see Butcher as a tragic victim. He did rob 600,000 dollars, which he then did keep for himself, thereby stealing from his accomplices, effectively putting himself in the fix that he is in. When apprehended, he could have turned in the loot to the authorities, thereby probably sparing himself from the gas chamber. He could have refused to accept his double-crossing former accomplice whom he himself betrayed to act as his attorney. Is this the stupidest criminal in the history of cinema? There is no redeeming quality to the fate of Butcher Benton.

Indestructible Man is often likened to Universal’s 1941 B-movie Man Made Monster (review), Lon Chaney Jr.’s first horror film. Chaney was hot off his success as Lennie in Lewis Milestone’s 1939 adaptation of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, and Hal Roach’s One Million B.C. (1940), and Universal saw in him a potential replacement for their former horror icons Boris Karloff, who had tired of playing monsters in heavy makeup, and Bela Lugosi, who wasn’t seen as bankable enough, and whose thick accent made him difficult to cast. The studio had a new monster in the production pipeline, The Wolf Man, with George Waggner set to direct, and decided to cook up Man Made Monster as a sort of “audition” for Chaney. Of course, he wasn’t just any up-and-coming actor, but the son of Universal’s original monster, silent star, “the man of a thousand faces”, Lon Chaney, whose name he had reluctantly adopted in order to further his career (Junior originally tried to make it under his real name Creighton Chaney). As the new ghoul on the Universal lot, his adopted name would hold enormous marquee value. Man Made Monster remains one of Chaney’s best horror movies, or at least one of his best performances, and follows a man who miraculously survives an electrocution, and is taken in as a guinea pig by a mad scientists who supercharges him in order to create an army of supermen at his bidding. However, the mute beast turns on his own master and then goes on a partly involuntary killing spree (his touch is deadly), before meeting is demise at a barb-wire fence, which drains him of his power. Jack Pollexfen denied that Man Made Monster influenced Indestructible Man in any way, but the similarities are too many to ignore — at one point the narration even refers to Butcher as a “monster made man”, which is a completely absurd choice of wording, unless as seen as a reference to Man Made Monster. In tone and plot, however, the film is probably closer to Edward L. Kahn’s 1955 movie Creature with the Atom Brain (review), another monster/gangster mashup. Even more so, the movie feels like a rehash of Warner’s The Walking Dead (1936, review), where pianist Boris Karloff comes back from the dead and starts executing the mobsters who set him up as a patsy for a killing. Directed by Michael Curtiz, The Walking Dead is a surprisingly strong film, benefitting from the fact that its titular avenger is actually innocent.

Indestructible Man’s box office earnings are not readily available, but in many parts of the US, the film had the privilege of being released as a double-bill with Invasion of the Body Snatchers (review) — in other parts it was coupled with World Without End (which will the the object of my next review). In Weaver’s book, the author quotes his research associate Robert J. Kiss, who notes that when coupled with the former, Indestructible Man reported good box office numbers, and when coupled with the latter, poor numbers. According to Kiss, this adds to a sense of “Indestructible Man as a near-irrelevance on the bill”. According to Weaver, the film’s supporting feature status also led it to receive very few reviews in newspapers, often just a mention at the end of the review of the main feature. Not even Variety, which seldom missed a picture, seems to have reviewed it. One of the very few trade papers that did give it a full review was Harrison’s Reports, which … reported … it as a “good horror type thriller” which “holds one on suspense throughout”. The critic noted “good direction and acting” and that “the manner in which Chaney tracks down his double-crossers one at at time and kills them makes for a number of spine-chilling situations”. All were not as positive. Alan Kass at the Florida Flambeau wrote that World Without End was a “fairly good and exciting thriller”, but lamented, “It is unfortunately teamed up with something like […] Indestructible Man“. And Theresa Loeb in Cone’s Way reported she found World Without End such a “silly item indeed” that she didn’t even stick around for Indestructible Man. British Monthly Film Bulletin called the film “a crude and dismal shocker with a mute Lon Chaney playing the title role with more energy than skill”.

One reason Indestructible Man has such a large cult following today is that, as stated, it was a staple on TV back in the day. Another one is that it is one of the films riffed on the TV show Mystery Science Theater 3000, or MST3K, in its fourth season in 1992, which has brought it a league of new “fans”. For a film to get the MST3K treatment is a double-edged blessing. On the one hand, many obscure and practically forgotten films have found new audiences through the show. On the other hand, being a show that specialises in riffing on bad movies, there are a few rather decent films whose reputations have been somewhat undeservedly tarnished because of their inclusion, like The Trollenberg Terror (1956) and Rocketship X-M (1951, review). There are probably those would gladly add Indestructible Man to the list as well.

Indestructible Man has a 4.3/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on over 2,700 votes. For IMDb, the rating is bad, but not terrible, and the number of ratings lifts it clear out of the “obscure” category. However, it has too few critic reviews for a Rotten Tomatoes consensus, and no Metacritic rating. Indestructible Man is not regularly featured on “worst films of history” lists, but it does make the cut on Flickchart’s list of the 100 worst SF movies of the 50’s, clocking in at number 31, and on Stacker’s list of the 100 worst SF movies in history, on place 51. However, as I’ve noted before, these kind of lists are often indicators of a film’s notoriety rather than its quality.

In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies Phil Hardy calls the film “a decidedly routine outing”. Film historian Bill Warren writes in his book Keep Watching the Skies: “Despite Lon Chaney Jr.’s strong performance in the title role, Indestructible Man is a flat, dull and unoriginal shocker, strictly bottom-of-the-double-bill fodder.” Barry Atkinson in the book Atomic Age Cinema argues that this is Lon Chaney’s finest moment in s 50’s SF/horror movie – not that this is particularly high praise. But Atkinson also notes that the film’s portrayal of the murders was unusually brutal for the time, and that the movie has a doggedness and a steely edge that lacks from meny similar products of the era. Leonard Maltin’s Classic Movie Guide gives the movie a decent 2/4 star review. In AllMovie’s 1.5/5 star review, Hans J. Wollstein writes: “A mix of sci-fi theatrics, heist melodrama, and Joe Friday “just-the-facts-ma’am” blandness, […] Indestructible Man is hardly the classic the video re-release artwork suggests. Incredibly cheap and attempting to mask a bad screenplay with tedious voice-over narration, Jack Pollexfen’s little treatise does have its unintentionally humorous moments, however”. TV Guide writes: “Strictly routine fare, and not very good at that”.

So, to return to my original question, what it is it that makes people give so much love to this film. After researching it, it seems the answer is: not very much, as most critics do not seem particularly fond of it. But still, it keeps being mentioned as something of a classic – more so than, for example, Man Made Monster, a much better movie with much fewer IMDb votes. But I suppose there is a sort of endearing silliness to it all, a wildly clashing mix of tones, from the Frankensteinean mad scientist to Max Showalter’s goofy attempt at Dragnet cop, the mindbending thought experiment of trying to imagine Marian Carr as a burlesque stripper, and no less as the boyfriend of Butcher Benton. Showalter is quite fun as the romantic lead, and Chaney does have his moments in the movie, even if I would have preferred to see the cut scenes of him talking. Plus, for friends of old Los Angeles, the film is a treat. As with many of Jack Pollexfen’s films, there’s the nagging feeling that it could have been really good. All the ingredients are sort of there, but somewhere along the way, the project just derailed.

Jack Pollexfen teamed up with Edgar Ulmer once more in 1958, to make the decent effort Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, starring to bad SF movie legends, John Agar and Gloria Talbott (no relation to Larry). He wrote, produced and directed his last movie in 1958, Monstrosity, but because of reasons we’ll get into later, it wasn’t released until 1963. He sold his last script, for a Z-western involving five females prisoners, in 1960. Pollexfen lived to the old age of 93, and he passed away in 2003. I can’t find any information on exactly what he did after 1960, when he would yet have been only 52 years old, but according to an obit by Tom Weaver, he went into semi-retirement in Mill Valley. In his later years he was incapacitated by diabetes and failing eyesight. In Weaver’s book on Indestructible Man, there’s a very sweet story written by Burl Lampert, who worked for six years as a reader for the half-blind Pollexfen, and struck up a deep friendship with him. Among other things, Lampert would read out the 40-or-so unproduced scripts (and perhaps 70 unfinished) that Pollexfen had lying around, and he would create voices for the characters, and under Pollexfen’s direction, they would record them all to tape, almost like radio plays, which Pollexfen apparently found great joy in listening to. But that’s another story.

Interviews with Sue Dwiggins, Vy Russell and Max Showalter paints a picture of Pollexfen as a passionate workaholic who was involved in all areas of production. He was also a producer who gathered around him a crew he could trust, and was loyal to many of his actors. William Schallert, who went on to a distinguished character actor career, was one of Pollexfen’s regulars, and appeared in a least half a dozen of his films. As one of the lead characters in The Man from Planet X, he was almost completely untested on the screen, but Pollexfen and Wisberg took a gamble on him that payed off. Says Schallert: “Jack Pollexfen once told me how they went about casting me: ‘We would cast as many parts in the picture as we could, and there would always be one left over that was a key part, but we couldn’t figure out who to cast in it. And I would always say to Aubrey, ‘Well, we gotta cast Bill Schallert. He can do anything.’’ And he somehow also managed to convey that belief to Albert Zugsmith, who then cast me in a lot of his pictures on the same premise, that I could do anything; that provided me with a fair amount of work over the years. For a character actor to be told [‘He can do anything’] early on by somebody who was in a position to hire him, was a real boost to my morale and to my belief in myself. I owe Jack a lot for that.” While both commercially and creatively successful, the partnership between Pollexfen and British-born Wisberg was not without its problems, and while Pollexfen was generally liked by all he worked with, Wisberg is described as a difficult person who get into feuds with people over perceived slights and disrespects and would hold long grudges. According to Pollexfen, after five years he had enough and decided to split up with Aubrey. Apparently, though, the friction did also create some kind of magic, as the careers of both fizzled out pretty soon after their breakup, even if Wisberg did have a couple of SF cult classics left under his belt, including Antonio Margheriti’s Snow Devils (1967) and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s debut film Hercules in New York (1970).

If Pollexfen was writer, producer, occasional director and unofficial production manager on his films, then Sue Dwiggins and Vy Russell quickly became the uncredited production staff. Personal friends of Pollexfen’s, as mentioned, they were the wives of Pollexfen’s two favourite cinematographers Bill Bradford and John “Jack” Russell, and they started pitching in on a voluntary basis as secretaries and assistants on The Man from Planet X, as they realised “phones would probably go unanswered in the Pollexfen-Wisberg office” during production. A funny story in Weaver’s book is that Sue recalls that Pollexfen had jokes that he and Wisberg would rather have blonde secretaries, so Dwiggins and Russell spent a whole day trying to dye their hair blonde — but both came out pink! According to Dwiggins, “Jack didn’t let on then, but he told me afterwards that it really scared him because when he saw what we’d done, he figured that both Bill and Jack were going to be absolutely furious [laughs]! He thought to himself, ‘Oh my God, Jack and Bill are gonna kill me!’”

Sue Dwiggins was born Miriam Gretchen Sues in Los Angeles in 1914, the daughter of a pioneering Hollywood couple, her father was a cameraman and her mother later became a sound editor. Sue started her career in the movies as a screenwriter for The Gene Autry Show on TV in 1950 and worked in Gene Autry’s production office in the fifties, when she was not working for Pollexfen and Wisberg. Her surname Dwiggins came from her first husband, a writer and journalist, whom she married in 1938, but later divorced. In 1952 she married cameraman William Bradford, who she met at Republic, which is why she is billed as Sue Bradford in the credits of Indestructible Man. In the 60’s she went in to work at Four Star Television and 20th Century Fox. In 1971 she had divorced once again, and married production manager Wallace Worsley, Jr., and subsequently started to work in his office. She worked on such prestige movies as The French Connection (1971), Deliverance (1972), Slap Shot (1977) and not least as production coordinator on E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982). According to an obit in Variety, she retired from the business after her husband’s death in 1991. IMDb lists additional credits for her in 1992 and 1993 as part of craft services, as “Susie Bradford“, but I suspect this is a case of mistaken identity. Sue Dwiggins was active in industry politics, and was a key player for getting production coordinators unionised in 1978. There is less information on Vy Russell, who only seems to have worked on Pollexfen’s movies in tandem with Dwiggins.

The editor of Indestructible Man is bad movie royalty, Fred Feitshans, Jr. Gransdon of silent movie star Ora, son of film editor Fred Feitshans, father of editor and producer Fred Feitshans III (better known as Buzz) and grandfather to cinematographer Fred “Buzz” Feitshans IV. Feitshans got his first crack at Hollywood as a freelancer with Edward Smalls Productions and Harry Sherman Productions, primarily editing low-budget westerns, before he got a contract with Universal in 1943. He also worked with Arch Oboler in 1941 at the ill-fated, dystopian propaganda movie Strange Holiday (1941/1945, review), in which Claude Rains returns from a fishing trip only to find that the Nazis have overtaken the USA because he joined a union. At Universal he made short films and B-movies, including some cult classics like Sherlock Holmes Faces Death (1943) with Basil Rathbone, The Mummy’s Curse (1944) and The Frozen Ghost (1945), both with Lon Chaney, Jr., as well as The Jungle Captive (1945, review), the second sequel to Captive Wild Woman (1943, review). After being let go by Universal in 1946, he worked freelance, including with Orson Welles on the film Black Magic (1949), the film which Welles later said “was the most sheer fun he had ever had working in the cinema”. The same year, he hooked up with notorious cut&paste low-budget producer Boris Petroff, and got his one and only directorial credit on Arctic Fury, a film primarily cobbled together from a number of older movies and documentaries. He also worked with Petroff on Two Lost Worlds (1951, review), another film which relied heavily on stock footage incorporated from at least three different films. In 1951 he was also hired by Pollexfen and Wisberg to edit The Man from Planet X, and subsequently became a part of their little family of filmmakers, working on a large number of their films, including Captive Women, Port Sinister and The Neanderthal Man.

After editing Murder is My Beat (1955) with Aubrey Wisberg and Edgar Ulmer, Feitshans worked for in TV for a few years, before hooking up with yet another infamous low-budget outfit, American International Pictures, home of such director/producers as Roger Corman and Bert I. Gordon. At AIP he edited half a dozen beach movies starring Frankie Avalon in 1964 and 1965 alone, with titles such as Muscle Beach Party, Bikini Beach and How to Stuff a Wild Bikini, and not least Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine (1965), starring the unlikely combination of Vincent Price and Frankie Avalon. He was soon promoted to head of the editorial department at AIP, which scored a surprise hit with the political comedy Wild in the Streets in 1968, and Feitshans must have been as surprised as everyone else to find that his editing was nominated for an Oscar. The award went to Frank Keller for Bullitt. Two other hits he edited at AIP were the cult SF/horror movie Frogs (1972) and the pseudo-biographical Dillinger (1975). In between his work on AIP, Feitshans also edited a dozen episodes of the “superhero” serial The Green Hornet (1966-1967), starring an as of yet fairly unknown Bruce Lee as the Hornet’s sidekick Kato. The legend of Bruce Lee grew after his death in 1973, and in 1976 Feitshans was again called upon to rework a number of The Green Hornet episodes into Fury of the Dragon, presenting it as Bruce Lee’s last film. This also remained Feitshans’ last film.

His son Buzz went on to become one of the conservative powerhouses in Hollywood, and in collaboration with John Milius made films like Hardcore (1979), Conan the Barbarian (1982), Red Dawn (1984) and Extreme Prejudice (1987). He also oversaw the production of films like Rambo III (1988), Total Recall (1990), Universal Soldier (1992), Die Hard: With A Vengeance (1995), Judge Dredd (1995), Nixon (1995) and Evita (1996). His son Buzz Feitshans IV came up through the industry as camera assistant on movies like Pale Rider (1985) and Stand by Me (1986), camera operator on The Mighty Ducks (1992) and Die Hard: With a Vengeance, and second unit DP on such fare as DragonHeart (1996), Daylight (1996) and The Scorpion King (2002). From 1994 on Buzz IV worked as cinematographer for low-budget films and TV movies, and from 2000 on almost exclusively in TV on a number of TV shows. He has occasionally worked as second unit director and in 2003 directed the straight-to-video action spoof Never Say Never Mind: The Swedish Bikini Team, perhaps as an homage to his granddad’s bikini era at AIP.

Art director Theobold Holsopple was another freelancing member of the Pollexfen-Wisberg family, who cut his teeth as production designer on Lippert Pictures‘ Rocketship X-M. He joined the “family” in 1952, and worked on, among others, Captive Women, Port Sinister, and Daughter of Dr. Jekyll. With Kurt Neumann, Irving Block and Jack Rabin he made the ambitious Kronos (1957, review), and with Lippert and Neumann The Fly (1958). In 1962 he was art director on Hands of a Stranger, yet another adaptation of Maurice Renard’s novel filmed in 1924 as The Hands of Orlac (review) and in 1935 as Mad Love (review). Finally, in 1968, he designed The Bamboo Saucer.

Indestructible Man actually had a production manager, Chris Beute, who, according to his obituary, had behind him a long career production and studio executive and a pioneer member of the Screen Directors Guild. He was the first manager of the Motion Picture Center — today Red Studios Hollywood — when it was rebuilt on the former site of he Desilu Cahuenga Studios in 1947. Beute had a directorial credit from 1938 and worked as assistant or second unit director on close to 20 movies, including the Pollexfen-Wisberg effort Problem Girls (1953). He passed away shortly after the completion of Indestructible Man.

Lon Chaney, Jr. soldiered on through the fifties and sixties, hard-working as ever and still in demand for TV guest spots and low-budget westerns as heavies and indians, and still making good on his reputation as a movie monster. His last major league film role came in 1958, when he appeared in a large supporting role in the western The Defiant Ones, directed by Stanley Kramer, who had also cast him in High Noon and Not as a Stranger. In 1958-1959 he co-starred in the first ever US-Canadian TV production Hawkeye and the Last of the Mohicans in 39 episodes, and in 1959 he hosted the anthology show 13 Demon Street, created by Curt Siodmak.

Right after the release of Indestructible Man, Chaney co-starred with Basil Rathbone, Akim Tamiroff, Bela Lugosi and John Carradine in The Black Sleep (1956), considered one of his better later films. He would go on to appear with Carradine in at least half a dozen movies before his retirement in 1971, including anthology films like Gallery of Horror (1967) and horror comedies like Hillbillys in a Haunted House (1967). Other memorable, if not always splendid horror or horror/SF films he appeared in was The Cyclops (1957, review), The Alligator People (1959), Witchcraft (1964) and Spider Baby (1967). Something resembling a prestige movie was The Haunted Palace (1963), one of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations, inspired by the story The Case of Charles Dexter Ward. Here he was third-billed below Vincent Price and Debra Paget. His last film was Dracula vs. Frankenstein, which he played mute, opposite J. Carroll Naish as Dr. Frankenstein and Zandor Vorkov as Dracula. His last film to be released was the ill-fated House of the Black Death, which begin production in 1965, but wasn’t finished and released in 1970. Although the film co-starred Chaney and Carradine as warlock brothers, the never shared a scene, as they filmed their parts at different times. The film was initially directed by Harold Daniels, but the producers thought the result was unreleasable, so they hired Jeremy Warren to shoot additional scenes. Despite being made in 1965, and released in 1971, it was shot in black-and-white. Chaney passed away in 1973, due to complications from his life of heavy drinking and smoking.

Accounts over what Chaney was like to work with differ, although most have described him as a hard-working, dedicated actor and a friendly, sweet man. His alcohol use did cause problems, though, and according to one account he was known as “the monster” on the Universal lot because his drunken behaviour sometimes “ended in bloodshed”. He infamously broke a vase over director Robert Siodmak’s head, and did not get along with his frequent Universal co-star Evelyn Ankers. To what extent his drinking influenced his acting capabilities is also a matter on which opinions differ, but the fact that he was so often cast as mute in later years does signal that he had significant problems remembering or delivering lines, or at least memorising new ones “after lunch”. In his final years he also suffered from throat cancer.

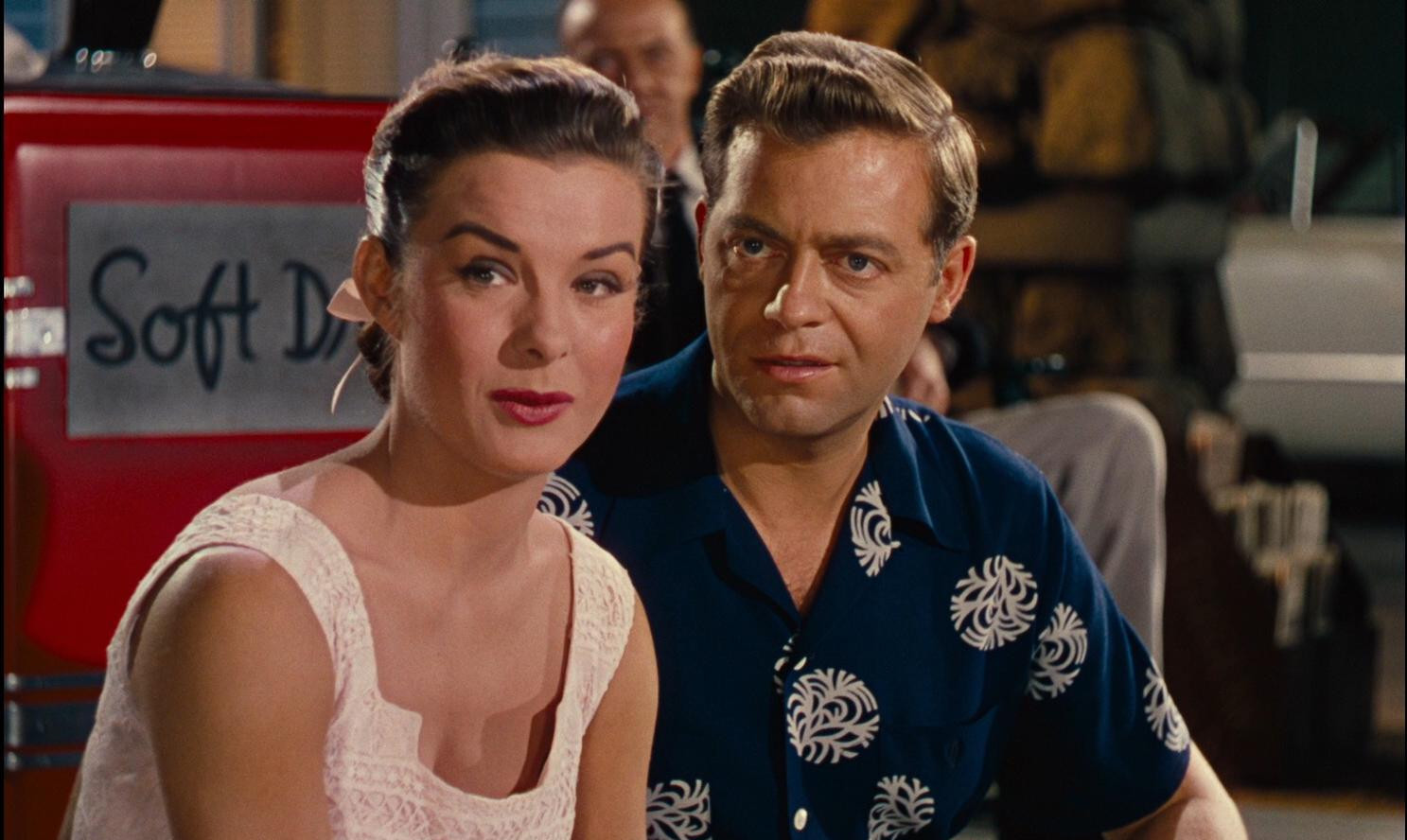

Max Showalter was not only a talented actor, he was also a singer, composer, pianist and painting artist. Originally a stage actor, he started his stage career at the Pasadena Playhouse in 1935, before moving up to Broadway in 1938. Particularly well at home in musicals, Showalter toured with Irving Berlin’s morale-boosting production This is the Army for two years between 1943 and 1945 (although he wasn’t in the original Broadway cast in 1942). According to both IMDb and Wikipedia, he played the male lead as Horace Vandergelder in the hit musical Hello, Dolly! “more than 3,000 times”, although this is clearly an error. According to both Playbill and The Internet Broadway Database, the musical was performed 2,844 times between 1964 and 1970, and the role was originated by David Burns, and Showalter was one of four subsequent replacements. According to Playbill, Showalter entered the production in March, 1967, and in November the same year, Cab Calloway took over the role in an all-black variation on the show opposite Pearl Bailey. It is possible Showalter returned to the role later, but he certainly didn’t perform it 3,000 times, and probably only held the role for half a year, playing against Martha Raye and Betty Grable in the title role. Whatever the case, this remained his most prestigious Broadway role.

In 1949 Showalter signed a contract as a featured player with Twentieth Century-Fox, and appeared in a number of supporting parts, bigger and smaller, in the early fifties. He is perhaps best remembered for his role as the unfortunate husband to Jean Peters who gets caught up in a murder plot between unhappy married couple Marilyn Monroe and Joseph Cotten in the 1953 Henry Hathaway noir Niagara. Other memorable roles include one of the “other men” in Vicki (1953), again with Peters, and Jeanne Crain, a large role in Dangerous Crossing (1953), with Crain and Michael Rennie, the murdered police officer at the heart of Naked Alibi (1954) and a small but memorable role as a magazine reporter in Bus Stop (1956), again with Marilyn Monroe. Twentieth Century-Fox gave him the more “sellable” screen name Casey Adams, under which he appears in Indestructible Man, but which he dropped in 1962. Under his own name he appeared, mostly in bit-parts, in films like The Music Man (1962), as the hotel desk clerk in the Doris Day vehicle Move Over, Darling (1963), Sidney Lumet’s heist movie The Anderson Tapes (1971), starring Sean Connery, the Blake Edwards comedy 10 (1979), best remembered for featuring a nude Bo Derek, in which he has a memorable role as the pastor who writes terrible songs, and John Hughes’ classic romcom Sixteen Candles (1984). Beside his work in film and the stage, Showalter appeared in over 100 TV episodes, mostly as a guest star, although he did have a recurrin role in The Stockard Channing Show (1980) and played six different characters in as many episodes of Perry Mason (1958-1965). As for science fiction he appeared in the cult film The Monster that Challenged the World (1957, review), the classic The Twilight Zone episode “It’s a Good Life” (1961) and in the TV series The Incredible Hulk (1981).

In his interview with Tom Weaver, Showalter says that there were a lot of things that attracted him to do Indestructible Man, despite it being very low-budget. The main reason was the chance to work with Lon Chaney, Jr., whom Showalter really liked and respected; “a nice, considerate, thoughtful man, and (I think) a very good actor”. Plus, there was a rare chance to play romantic lead, plus playing the “Joe Friday” cop: “It was fun because it was so far away from me, that kind of thing. I was surprised they asked me, but I was tickled to death to do it, because it was another ‘character’ kind of thing.” Upon re-watching the movie for Weaver’s 1984 interview, Showalter says he didn’t find it as bad as he thought it would be, and he wasn’t at all embarrassed to be in it.

When Eva tells Dick Chasen about her life’s history in one of the over-long dialogue sequences in Indestructible Man, she relates how she won a movie studio audition in a modelling contest and moved to Los Angeles. In fact, this was not far from the fate of actress Marian Carr, who won a beauty contest in Chicago and moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in acting. After a stint at the Pasadena Playhouse, she was, unlike Eva, contracted by RKO in 1946. However, her career didn’t go very far at RKO and she soon took a hiatus for marriage and child-rearing. Carr returned to acting as a freelancer in 1952, dividing her time between B-movies, like Northern Patrol (1953) at Monogram, where she played, of all things, a gunslinger, and TV. She had a couple of other run-of-the-mill leads in low-budget fare, when she was not relegated to supporting player. One of her most successful, and memorable, turns was in Robert Aldrich’s ensemble piece Kiss Me Deadly (1955). She had slightly better luck in TV, and just prior to filming Indestructible Man she had come off a couple of well-noticed turns in shows like Four Star Playhouse and Schlitz Playhouse of the Stars. Gossip columnist Erskine Johnson in his famed column Hollywood Notes called Carr the “Marilyn Monroe of Television”, and claimed she had been “overheating the tubes”.

However, she isn’t overheating much of anything in Indestructible Man — but apparently Johnson’s talk about her being he next Marilyn had caught on, because Showalter tells Weaver that when re-watching the movie he realised how much she tried acting like Monroe in some of the scenes. In an interview with VideoScope Magazine he said: “She was very difficult to work with; she didn’t quite give as much as I like to get from fellow performers”. Vy Russell and Sue Dwiggins don’t remember any problems on set with Lon Chaney, Jr., but they both tell Weaver that Carr caused the production team a lot of headache. Says Dwiggins: “She wasn’t temperamental in a way like she thought she was the queen bee or something, but she’d get upset. And you can’t really afford a lot of that when you’re shootin’ on a shoestring.” According to Dwiggins, one day she got mad and locked herself into her dressing room and refused to talk to anyone, while everyone else were ready to start filming a scene. She finally agreed to talk to Dwiggins, but when interviewed by Weaver, she couldn’t even remember what it was that Carr had been upset about, only that it was something quite trivial that she had been holding up the entire production for. Vy Russell suspects that Carr was simply “insecure in this potboiler of a movie that she wasn’t sure about”, and that’s why she kept having problems. Carr retired from acting in 1956.

We have seen Ross Elliott before on this blog, most notably as the male lead in the dreadful 1955 hee-haw comedy Carolina Cannonball, where he and cornpone comedienne Judy Casanova thwart communist spies who try to get their hands on a nuclear-powered locomotive that Casanova’s Grandpa has built in a western ghost town. Unfortunately for Elliott, the film probably features the most inept “hero” of any Hollywood movie in history. During the length of the film, he succeeds in absolutely nothing else than getting caught and tied up by the villains. Described as a “general utilitarian player”, New Yorker Ross’ clean-cut and somewhat nondescript features and a reliable talent provided him with a steady income for over four decades. Few of his film roles stand out as memorable, and he might be best remembered for walking out on his role as Lee Baldwin in the long-running soap opera General Hospital in 1965, a role which was then played by Peter Hansen from 1965 to his retirement in 2004. Leaving behind a proposed career in law, Ross came up through Broadway and moved to Hollywood after serving in WWII. Between 1943 and 1986 he appeared in close to 200 TV shows and over 60 films. He had robust supporting roles in SF movies like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), Tarantula (1955, review), and Indestructible Man, as well as that rare lead in Carolina Cannonball, and he showed up in smaller roles in Monster on the Campus (1958) and The Crawling Hand (1963). He also appeared in a number of SF TV shows, including The Twilight Zone, The Time Tunnel, The Invaders, Wonder Woman and The Bionic Woman.

Robert Shayne had a long and prolific career on stage, in film and TV, without ever becoming neither Broadway nor Hollywood nobility. He is probably best known for appearing in close to 100 episodes of Adventures of Superman (1952-1958) as Inspector Henderson. Indestructible Man was Shayne’s second outing as mad doctor in a Pollexfen film — he played the lead as the obnoxious creator of the titular character in The Neanderthal Man in 1953.

He had a string of supporting roles in A films in the forties, notably opposite Bette Davis in Mr. Skeffington (1944) and Barbara Stanwyck in Christmas in Connecticut (1945), and is sometimes remembered for his brief turn opposite Cary Grant in North by Northwest (1959). More often, however, he was cast in small, prominent or even leading roles in B movies, such as The Spirit of West Point (1947), sometimes described as the worst sports movie ever made.

Apart from his six-year tenure at Adventures of Superman, he appeared in numerous sci-fi films, such as Invaders from Mars (1953, review), Tobor the Great (1954, review), Indestructible Man, the infamous The Giant Claw (1957, review), Kronos (1957), How to Make a Monster (1958), The Lost Missile (1958), Teenage Cave Man (1958) and Son of Flubber (1963). In the sixties and seventies he was mainly seen on stage and on TV, and he practically retired in 1977 after nearly 50 years in the film business. He made a brief comeback in 1990-1991, then 90 years old, in two episodes of the TV series The Flash, as a newsstand salesman. He was actually blind at the time, and learned his lines by having his wife read them out for him.

There are so many interesting characters on the cast sheet of Indestructible Man, that almost all of them deserve a post of their own. Oddly enough, some that don’t even have lines are credited on screen, such as Madge Cleveland, as “Screaming woman”, whole some with central supporting parts, like Joe Flynn as Dr. Bradshaw’s assistant or Marvin Press as Squemy Ellis, don’t. This probably has to do with Jack Pollexfen’s loyalty to his regular actors: featured players were paid more.

Stuart Randall, playing the police captain, was a singer and stage actor, whose rugged features and stature made him a staple in in western films and TV series in the fifties. Between 1950 and 1971 he crammed in at least 150 film or TV appearances, appearing on nearly every major western series at least once. Randall also had a major role in Captive Women. Ken Terrell, playing Joe, one of Chaney’s victims, was a bodybuilder who in 1922 entered the “Most Perfectly Developed Man” contest, but lost to Charles Atlas. However, he returned, and won the contest in 1925, and at least once more in 1927. After working as a shop window model New York, he tried his luck at vaudeville in Chicago before packing for Hollywood, where he established himself as a stuntman and actor in he mid-30’s. He soon became one of the most sought-after stuntmen in the business, and appeared in some 400 films, serials or TV shows between 1934 and 1966. However, he had a bad leg injury when filming a car commercial in 1958, which he was never quite able to recover from, and continued eking out a living with more straight acting, to mediocre results. In Indestructible Man Terrell spends the entire film on crutches, and given his profession, it’s not far-fetched to think that this was not scripted. Very likely, Pollexfen gave his old friend a break by offering him a role at a time when he was injured and had a hard time supporting himself. At Republic, Terrell was also a staple in many of the studio’s science fiction serials; Mysterious Doctor Satan, The Green Hornet Strikes Again, Adventures of Captain Marvel, Captain America, The Purple Monster Strikes, The Crimson Ghost, The Black Widow, The Invisible Monster, Flying Disc Man from Mars, Radar Men from the Moon and Zombies of the Stratosphere. He also appeared in the SF movies The Thing from Another World (1951, review) as a stuntman, Port Sinister, The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) in a featured role, Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958) in a featured role and Master of the World (1961), uncredited.

Joe Flynn began as a ventriloquist and radio performer, and spent WWII entertaining the troops. After the war he made the move to Los Angeles, and in 1954 made his film debut. Apparently, Indestructible Man was the movie that convinced him to pursue a career in comedy, as audiences laughed at his character, even though he was playing it straight. He quickly made a move to television, where he achieved comedy immortality when cast as Captain Wallace ‘Leadbottom’ Binghamton in the classic McHale’s Navy (1962-1966). He later appeared in nine Disney films, including Son of Flubber (1963) The Love Bug (1968), The Million Dollar Duck (1971) and most memorably as Dean Higgins the Kurt Russell vehicles The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1969), Now You See Him, Now You Don’t (1972) and The Strongest Man in the World (1975). Marjorie Stapp was an occasional low-budget western lead, perhaps best remembered for playing Queen Guinevere opposite Superman George Reeves as Galahad in The Adventures of Sir Galahad in 1949. She also appeared in minor roles in Port Sinister, The Werewolf (1956, review), Kronos and The Monster that Challenged the World.

Janne Wass

Indestructible Man. 1956, USA. Directed by Jack Pollexfen. Written by Jack Pollexfen, Sue Dwiggins, Vy Russell. Starring: Lon Chaney, Jr., Max Showalter, Marian Carr, Ross Elliott, Stuart Randall, Ken Terrell, Marjorie Stapp, Robert Shayne, Peggy Maley, Robert Foulk, Reita Green, Roy Engel, Madge Cleveland, Joe Flynn, Marvin Press. Music: Albert Glasser. Cinematography: John Russell. Editing: Fred Feitshans, Jr. Art director: Theobold Holsopple. Produced by Jack Pollexfen for C.K.G. Productions & Allied Artists.

Leave a comment