Edward Jekyll tries to clear his family name by recreating his father’s experiments, but a scandal-hungry society, his friends and even his own sanity seems to conspire against him. A laudable, but meandering 1951 low-budget effort from the pen of Jack Pollexfen. 4/10

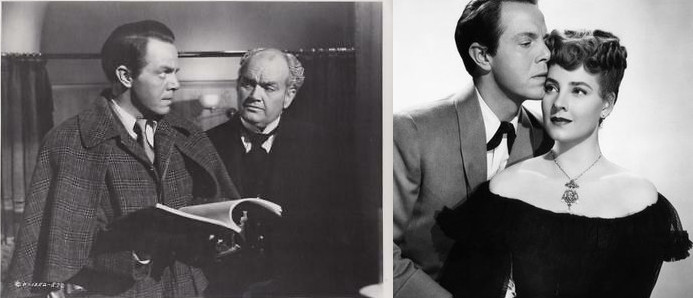

Son of Dr. Jekyll. 1951, USA. Directed by Seymour Friedman. Written by Jack Pollexfen, Mortimer Braus, Edward Huebsch. Inspired by novella by Robert Louis Stevenson. Starring: Louis Hayward, Jody Lawrance, Alexander Knox, Lester Matthews. IMDb: 5.0/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 83/100. Metacritic: N/A.

1951 gave the world not one, but two cinematic interpretations of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde story. The first was the moody Argentine The Strange Case of the Man and the Beast (review), in which Jekyll gets a wife and a son, and the central conflict becomes one of family values. The other, oddly enough, actually features the son of Dr. Jekyll and is a Columbia low-budget production.

The Son of Dr. Jekyll opens in medias res in 1860, as we follow the final moments of the well-known cinematic story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (although set 30 years earlier than usual). After a murder — in this case the murder of his wife — Hyde flees a torch-wielding mob, Frankenstein-style, through the streets of London to his lab. While he mixes the antidote to his personality-changing potion, the mob sets fire to the building. In his final moments, Dr. Jekyll falls to his death from a window when trying to escape the flames. We then meet Jekyll’s friends, John Utterson (Lester Matthews) and Dr. Curtis Lanyon (Alexander Knox), and it is revealed that Jekyll left behind an infant son, whom Utterson adopts as his own.

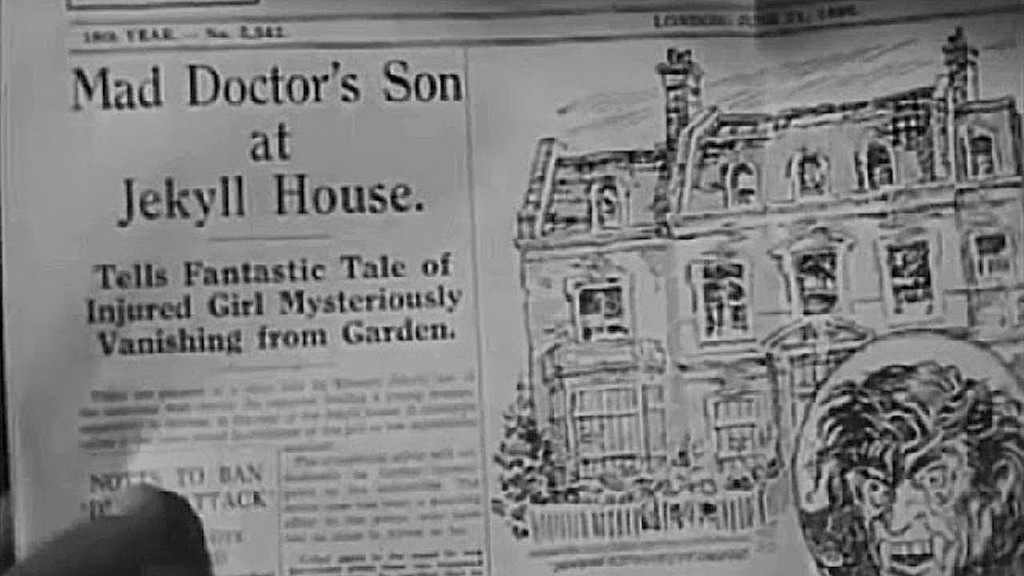

Cut then to 1890, when Edward Utterson, henceforth known as Edward Jekyll (Louis Hayward), is about to turn 30 and 1) wed his girlfriend, Utterson’s daughter Lynn (Jody Lawrance), and 2) take possession of his father’s estate, most importantly his half-burned and boarded up laboratory. However, to this day, Edward has been in complete ignorance of his macabre heritage, and as a pre-birthday present, Dr. Utterson finally reveals to Edward that he is indeed the son of that infamous “monster” Dr. Henry Jekyll, generally believed to have murdered his wife in a fit of rage-filled madness. Turns out Edward is something of a rogue scientist himself, having been thrown out of his university due to “immoral” research, which is alluded to but never fully explained. Instead of trying to escape his past, Edward decides to take up residence in the old Jekyll house and continue his father’s work, despite the neighbourhood whispering behind his back and the press trying its best to set him up as Mad Doctor, Jr.

The premise of the film is thus: The world thinks Henry Jekyll was a deranged monster. Edward believes that by proving that his father invented a potion that turned him into a deranged monster, the world will realise that he was, in fact, a brilliant scientist, thus clearing the family name of its dark shadow. However, despite following his father’s notes on how to make the potion to the letter, Edward fails time after another, growing ever more frustrated. Meanwhile, the press, led by the sneaky editor Daniels (Gavin Muir) set him up in precarious situations in order paint him as the violent madman they think his father was. Edward gets no help from Inspector Stoddard of the Scotland Yard (Paul Cavanagh), who thinks he is off his rocker. And people from the murky past of the family turn up throwing accusations against his father. It doesn’t help that Edward responds to these situations by losing his temper and letting his fists speak where his words fail — or that editor Daniels always seems to be conveniently present to document these moments with his camera. Finally he is set up for a case of child abuse he has not committed and is sent for observation to Dr. Lanyon’s sanatorium.

Dr. Lanyon, throughout all of this, unbeknownst to Edward, but knownst to the audience, has been acting fishy. The one time Edward has briefly been able to turn into Hyde is only after Lanyon has secretly snuck into his lab and added a secret mixture to Edward’s concoction. Believing he has finally succeeded, Edward calls local law enforcement, the scientific community and the press to his lab, now ready to demonstrate his findings. But the new potion, now without Lanyon’s secret ingredient, fails, and Edward is officially labelled a lunatic. At this point, Edward himself starts having doubts about his own sanity, and his frequent violent outbursts raise worries in his mind that perhaps his father was actually a madman and that he might have inherited the insanity. On the other hand, he does feel like he is being set up, and decides to dig deeper …

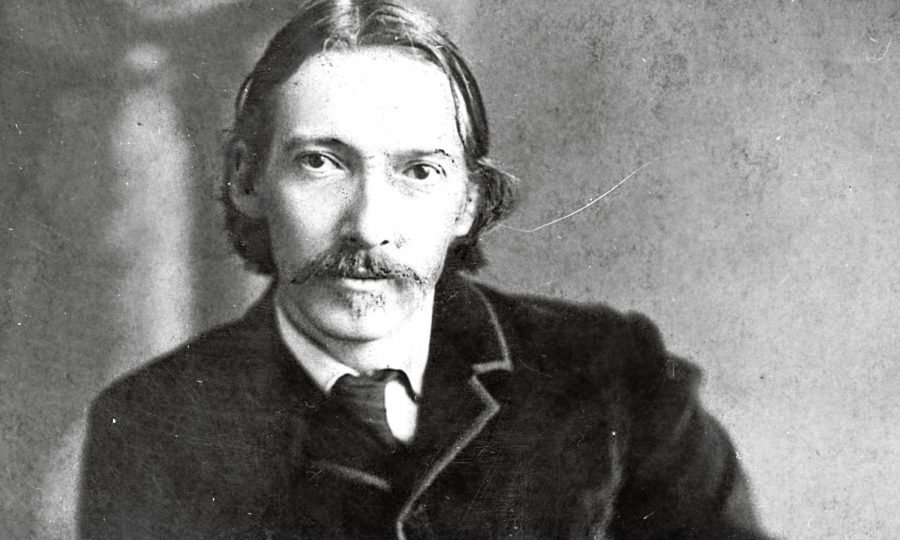

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote his famous novella in 1886 — if legend is to believed, he finished the first draft in three feverish days. Stevenson was already a literary star, famous for reinventing British short prose with stories like The Suicide Club, The Rajah’s Diamond and The Pavilion on the Links, in the early 1880s, and most importantly, for his dark pirate adventure story Treasure Island (1883). Stevenson was also a central figure in the re-emergence of Gothic fiction at the turn of the century, with The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as a sort of unofficial starting gun for a wave of macabre fin-de-siècle gloom. A thread running through much of Stevenson‘s work is a critique of Victorian society, its hypocrite aristocratic traditions and ethics, its class divide and imperialism. His South Island tales from the early 1890s were some of the Britain’s earliest anti-colonialist fiction.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde became a world-wide bestseller, the audience merrily giggling as they allowed themselves to take on this scandalous tale of violence and indulgence. The book tackled the question of human duality: the idea of the animalistic side of us built in as a legacy from our evolutionary ancestors — a topic eagerly discussed in the decades after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origins of Species (1859). This was Original Sin given a scientific explanation. On the other hand, one could argue that from a moral perspective, the animal side of us is no more “evil” than our plastered-on “civilisation”, and no less sinful, and in suppressing our “darkness” we remain inhibited and unable to live up to our potential. In his novella, Stevenson’s character Dr. Jekyll struggles with these questions, and comes to the conclusion that the darkness needs an outlet, it needs to be ventilated and acted upon, otherwise it remains in the spirit as a gnawing, nagging insistence. But of course, in practical terms acting upon animalistic urges also bring upon regret, misery and most importantly, exclusion from civil society. What then, figures Jekyll, if one could create a split personality, dissimilar enough in appearance and voice that nobody would recognise him as a version of the “original”, and in the guise of this visage act upon all “immoral” urges, in order to cleanse them from the system, thus leaving the “original” personality free to conduct all his waking time to constructive, civilised and moral enterprises. And as we know, this strategy didn’t turn out too well for Dr. Jekyll.

The tale was further popularised by a string of stage adaptations in the 1890s. These adaptations radically altered the structure of the story and added characters and plots not present in the original, such as the fiancée and the father, and made the central premise Jekyll’s faithfulness to his (naturally chaste) betrothed vs. his sexual desire. As with a lot of early cinema, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was primarily adapted from the stage, and not from the source novella. It was hugely popular as a source for cinematic adaptation in the early years of moving pictures, and has been quoted as the most frequently adapted literary story in film history, with over 100 confirmed adaptations (including comedy animations and TV episodes). Three Hollywood major studio feature films were produced in the twenties, thirties and forties, starring John Barrymore (1920, review), Fredric March (1931, review) and Spencer Tracy (1941, review).

The Son of Dr. Jekyll takes its beats from the last of these versions. This version had Jekyll’s lab go up in flames in the end, and like The Son of Dr. Jekyll it features an athletic Mr. Hyde leaping over rooftops. Director Seymour Friedman also borrows Victor Fleming’s stately but dark vision of Victorian London. However, after a kinetic opening sequence with impressive stunts, the film settles into a much more mundane rhythm with tightly cropped cropped images and a lot of statically filmed conversations in often nondescript rooms. The attention to period detail (the film is set in 1890’s London, despite taking place 30 years after the events in the novella) by art director Arthur Holscher and later Oscar winner, costume designer Jean Louis, is welcome, though. Director Friedman and prolific low-budget noir specialist, cinematographer Henry Freulich, occasionally impress with flashes of German Expressionist brilliance. While the production shows all the telltale signs of a tight budget (it is a Columbia B picture, after all), it uses its resources wisely.

The acting from the cast of expat Britons is good to decent all around. Of course, any adaptation of this story stands or falls with its lead, and at least The Son of Dr. Jekyll doesn’t fail because of its star actor, Louis Hayward, although he might seem a somewhat odd choice. He is presented with a thankless task, though, to play Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde without ever actually getting to the fun part of the dual role. But this low-budget Errol Flynn turned noir staple has enough charisma to carry the movie on the strength of Jekyll alone. He is well backed by Oscar nominee and Golden Globe winner Alexander Knox as Dr. Lanyon, playing a character you’re never quite sure who’s side he’s on. Jody Lawrance gets an unusually fleshed-out role as Jekyll’s fiancée, and carries it out with dignity. The remaining seasoned character actors could do this in their sleep.

As the plot synopsis above should indicate, anyone expecting an old-fashioned horror film will be disappointed. Nonetheless, Columbia had no problem advertising it as such, making this a classic bait-and-switch production. This isn’t necessarily a problem in and of itself if the movie works while surprising the audience with something unexpected. However, while The Son of Dr. Jekyll does surprise to the extent that it isn’t the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde story that the poster advertises it as, period audiences probably had a somewhat difficult time pinpointing what the film actually is. The script was written by low-budget writer and sometimes producer Jack Pollexfen from a story by himself and Mortimer Braus. In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, Pollexfen says that he and Braus were “kidding with outlandish film titles” one day, and came up with “The Son of Dr. Jekyll”. According to Pollexfen, the two thought about it for a while, figured it could sell, and “knocked out a quick story”. They had nothing to do with the production after Columbia bought the story, and the screenplay was finished by blacklisted writer Edward Huebsch, who consequently received no credit.

Pollexfen had previously turned out the script for (and produced) the tight little alien invasion film The Man from Planet X (1951, review), which, despite an abysmally low budget, had some interesting ideas and fascinating enough characters. Likewise, there are many good ideas in The Son of Dr. Jekyll. The problem is that Pollexfen and Braus haven’t been able to choose which ones to choose and which ones to leave out, so they’ve left them all in. In the beginning we are made aware of Edward’s experiments that get him thrown out of university — he is apparently told that “we should learn to take care of our own species before trying to create new ones”. This certainly peaks a viewer’s interest, but these experiments are practically never referred to again. Then there’s a subplot with a father and a daughter, apparently actors, who are hired to play “roles” which get Edward into trouble. The characters are fleshed-out enough to warrant a more substantial story; there’s hints of a troubled father-daughter relationship and the girl, Hazel (Claire Carleton), seems to be set up as a secondary love interest for Edward, mirroring the original Jekyll/Hyde story, but the two are abruptly killed off mid-movie. When Jekyll briefly turns into Hyde, it seems we are on track with the original plot, but that, as stated, goes nowhere.

There are three major and parallel themes/potential plots running through the film. First, there’s the question regarding Edward’s sanity, which seems to take the upper hand when he is assigned to Lanyon’s sanatorium, but he remains there for a full five minutes of the movie before that idea is waved off as well. This idea suggests an exploration of the Jekyll/Hyde conundrum from a psychological point of view, something like which was explored in the 1924 German minor gem The Hands of Orlac (review). This would have made an interesting film. Second, there’s the parallel plot involving the public fear and mistrust of Edward, fuelled by sensationalist media, bullying him into slowly becoming the monster they see him as. This would suggest an exploration of the Jekyll/Hyde conundrum from a sociological point of view, of the fear of the monstrous “other” manifesting itself physically in the object of the alienation. This would also have made an interesting film. The third and least interesting of these three parallel plots is the much more prosaic one involving a Charlie Chan-like revenge mystery plot with an innocent protagonist being set up by a friend. And unfortunately, this is the plot that Pollexfen and Braus ultimately run with. Interestingly, Pollexfen returned to the scene of the crime in 1957, writing and producing Daughter of Jekyll, a more traditional horror exploitation film.

Subverting audience expectations is not bad in itself, but substituting several potentially interesting narratives with a fairly dull one is rarely a good idea. Throwing in a red herring or two serves to keep the audience on its toes, but this film is like a school of fish in an aquarium and the audience is pulled in so many directions that it finally doesn’t know what it is watching. This said, there is a laudable attempt here at turning the tables, making not Jekyll/Hyde the monster ravaging society, but rather making society the monster turning Jekyll into Hyde. Through all the different strands in the film, London emerges as the culprit of of this re-imagined tale, bringing Stevenson’s novella into Frankensteinean territory.

TV Guide gives the movie 1/4 stars, and AllMovie 1.5/5, both without elaborating. The film does have its defenders, though, some of them quite ardent. Nige Burton at Classic Horror calls it “a true hidden classic” and “a grown-up and satisfying film”. Still, most reviewers, like Derek Winnert, see it as “contrived”, but still “reasonably entertaining hokum with okay performances and good, moody black and white cinematography by Henry Freulich. But the production values and screenplay are fairly feeble, and horror movie shocks and scares are desperately scarce.” Winnert gives The Son of Dr. Jekyll 3/5 stars. Justin McKinney of The Bloody Pit of Horror awards it 2.5/5 stars, but in his writing feels more positive than Winnert: “Where this film is unexpectedly strongest however is in its depiction of a judgmental society unwilling to let go of the past”. Mark David Welsh feels the film is “slapdash” and filled with “ridiculous contrivances”, but still “a fairly painless way to spend 78 minutes”. Then there are those who simply don’t like the bait-and-switch. Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum writes in his 2/5 star review: “The movie isn’t really about monster transformations and murders. It’s more about dealing with an unwanted family legacy and coming out of your father’s shadow. In that respect; it works. Still, anyone wanting a full-on Jekyll and Hyde movie (like me) will undoubtedly be disappointed.” Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings writes: “The problem is that the movie promises certain types of thrills and then substitutes a series of mediocre and disappointing mundanities in their place”.

The Son of Dr. Jekyll is not a terrible movie. As stated, it has a lot of good ideas, it is competently made and well acted, with occasional flashes of visual creativity. There’s a tendency, in particular among B movie fans, to overstate the “intelligence” or “thoughtfulness” of a film as soon as it brings in a bit of philosophy or social critique. In this case, the screenwriters throw a bunch of ideas at the wall, hoping some of them will stick, and that’s not the way to craft an intelligent script, even if the ideas themselves rise above what you would normally get in a low-budget horror programmer. But conversely, there’s also a tendency to write off a film because it doesn’t deliver the expected gore and monster action and instead focuses on more “grown-up” themes. But this is not an objective way of reviewing a film — you can’t fault a film for what it isn’t, but should review it for what it is. If the advertising is misleading, then that is certainly worth mentioning, but writing that a film sucks just because you were promised dinosaurs and there were no dinosaurs is, of course, childish.

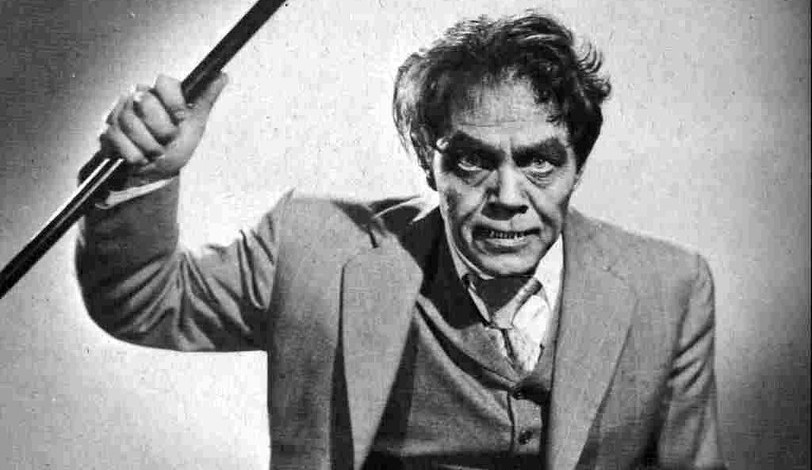

All in all, I found The Son of Dr. Jekyll toyed with a number of interesting premises, but had too many entry points and half-baked subplots that went nowhere, leading to viewer fatigue. Others seem not to have been as bothered by this as me, and I concede that the film is occasionally quite entertaining and well crafted for a B movie, from a technical and artistic perspective. The brief transformation scene is really quite good, and I don’t think makeup artist Clay Campbell gets enough credit these days. More on him below. The technique Campbell used for getting the makeup to appear on Hayward without cutting was hugely effective, but it wasn’t new. In fact, Campbell copied it straight from Fredric March’s transformation in Paramount’s version of the film, and used coloured filters to either block out or highlight painted-on makeup. The principle is really extremely simple, but very effective. But despite all the good details and qualities of the film, ultimately the meandering script created pacing problems, and the movie just didn’t pull me along.

Director Seymour Friedman was a Columbia stalwart who came up through the ranks as assistant director in the forties, and started directing B movies for the studio in 1948. Extremely prolific, he managed to rack up over a dozen titles in the three years before making The Son of Dr. Jekyll, and is perhaps best remembered for a couple of Boston Blackie entries. In the late fifties, he switched to television, where he became a successful production supervisor for shows like Dennis the Menace, Bewitched, Hazel, Gidget and The Donna Reed Show.

Writer Jack Pollexfen has a pretty decent SF pedigree. A newspaper reporter, he got into the movie business in the early forties when MGM wanted him to turn one of his articles into a movie script. His budding career was interrupted by the war, as he served four years writing education and information films for the US air force. Upon returning he formed a company with English-born Aubrey Wisberg, with whom he produced and wrote a good dozen films low-budget films between 1949 and 1955. Wisberg and Pollexfen specialised in two genres. One was the re-imagining of famous historical romances, with films such as The Treasure of Monte Christo (1949), The Lady in the Iron Mask (1952), Captain John Smith and Pocahontas (1953) and Return to Treasure Island (1954). The other one was the one they would be remembered for: science fiction. The duo wrote and produced the afore-mentioned The Man from Planet X, the post-apocalyptic tribal women exploitation film Captive Women (1952, review) and The Neanderthal Man (1953). As stated, Wisberg was not involved in The Son of Dr. Jekyll, and by 1957, when Pollexfen wrote Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, the partnership had already ended.

In 1956 Pollexfen directed Lon Chaney, Jr. in the low-budget SF movie Indestructible Man (review), essentially an uncredited remake of Chaney’s earlier movie Man Made Monster (1941, review). He also produced and co-wrote the infamous Monstrosity in 1958, which wasn’t released until 1963. A plagued production, Pollexfen fired the director and finished directing the film himself. The production company ran out of money halfway through, and tried fixing the film in post over the next years, but according to Pollexfen it was doomed to fail. Pollexfen went into semi-retirement after the release of Monstrosity and passed away in 2003. For more on Pollexfen, please see Tom Weaver’s well-researched obituary.

Louis Hayward is the somewhat unlikely star of the movie — carrying on the tradition of bona fide matiné stars playing the dual role of Jekyll and Hyde. Not quite the match for the likes of John Barrymore or Spencer Tracy, Hayward was nonetheless a marquee name in the forties and early fifties. Born in Johannesburg, he worked his way up the career ladder on stage (and in a few films) in Britain, largely thanks to being taken under the wings of superstar Noel Coward, with whom he relocated to Broadway in 1935. After impressing in the lead of what has been described as Coward’s worst play (which was a flop), he caught the eye of Hollywood producers, making a name for himself as a charismatic and versatile actor with heaps of sex appeal. His breakout role was that of the original James Bond, namely The Saint, in the first movie about the British playboy Spy, The Saint in New York (1938). He continued the success with the dual title role in James Whale’s 1939 rendition of The Man on the Iron Mask for Edward Smalls Productions.

Smalls built Hayward up as a mid-budget swashbuckling hero, a budget version of Errol Flynn, often with Rowland V. Lee or Gordon Douglas directing. He was also a favourite of Edgar G. Ulmer’s tense noirs, most notably Ruthless (1948). But he also starred in romantic dramas, comedies, period dramas and straight thrillers. Among his best remembered roles are that of Philip Lombard in René Clair’s famous rendition of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (1945) and Fritz Lang’s noir House by the River (1950). He teamed up with Pollexfen and Wisberg as D’Artagnan in The Lady in the Iron Mask before gradually shifting into guest starring on TV. Hayward still made the odd film now and again, he, for example, returned to the role he helped originate fifteen years prior in The Saint Returns (1953), appeared in the western Chuka (1967) and had a part in the B-star-studded Terror in the Wax Museum (1973). He passed away from lung cancer in 1985, due to a habit of smoking three packs of cigarettes every day.

Leading lady Jody Lawrance (real name Nona Goddard) was a Texas-born Californian who at one time as a child, due to troubled family affairs, lived with a likewise young Norma Jean Baker — later of course known as Marilyn Monroe. After taking drama lessons as a teenager, she managed to secure a contract with Columbia in 1949, and her career looked promising as she was immediately assigned leading lady roles in the studio’s B movies. However, a headstrong woman with bigger dreams, she felt overlooked at Columbia, and broke off the contract in 1952, only to find herself horribly miscast in the Edward Smalls production John Smith and Pocahontas (1953). The fair-haired, blue-eyed Lawrance was, admittedly, not quite the ideal actress for playing the Native American child bride. The film flopped and her career tanked, finding Lawrance working as a waiter at an ice cream café, when her former co-worker Burt Lancaster one day walked in with director Michael Curtiz, who took an interest in her and signed her to Paramount, who, unfortunately, dropped her the next year, due to her secret marriage and pregnancy. After having her child, she tried to reignite her career, and made the odd movie and around a dozen guest appearances on TV, but left the business in the early sixties.

Playing the villain of the piece, Alexander Knox brings his usual intelligence and diversity to the role. After studying English literature, the Bostonian worked as a journalist and stage actor before relocating to London in the mid-thirties in search of “serious” stage roles. A successful stage and film career in Britain was interrupted by WWII, which prompted his return to the US in 1939, followed by success on Broadway and finally Hollywood in 1941, where he was immediately recognised as a reliable character actor. He is best known for his portrayal of US president Woodrow Wilson in Darryl F. Zanuck’s ponderous flop Wilson (1944), which, despite the problems with the film, earned him an Oscar nomination and a Golden Globe win. However, his successful Hollywood career was interrupted by Knox being blacklisted in Sen. McCarthy’s communist hunt in 1952, and he once again relocated to London, where he remained for the rest of his life, carving out a successful career as an actor (stage and film) and a writer. He did a few SF productions, including the SF horror cult classic The Damned (1952), Andrew Marton’s Crack in the World (1965), and had a bit-part as the US secretery of defense in the James Bond spy-fi You Only Live Twice (1967). Other memorable outings came in films like the Kirk Douglas vehicles The Vikings (1958) and Holocaust 2000 (1977), The Longest Day (1962), Modesty Blaise (1966), Khartoum (1966), Nicholas and Alexandra (1971), Gorky Park (1983, filmed the year I was born in my hometown Helsinki) and the TV series Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979).

Playing Utterson is one of the many Brits carving out a living in Hollywood doing bit parts in swashbucklers and historical romances requiring a certain accent, Lester Matthews. He appeared in at least three Robin Hood films in his career, including the definitive one, The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), with a glorious Technicolor Errol Flynn. Matthews also gets some genre props for his supporting roles in Universal’s Werewolf of London (1935) and The Raven (1936), starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. All in all, Matthews appeared in well over 200 films or TV shows in his career.

Chicago-born Gavin Muir and Canadian Paul Cavanagh as editor Daniels and Inspector Stoddard, respectively, were both Broadway fixtures who found themselves wanted as Hollywood character actors with the advent of talking pictures. While Muir also had a knack for playing villains, both actors were particularly in demand for roles that required some sophistication and a British accent (which Muir aptly faked, while Cavanagh had the advantage of both his Canadian background and studies at Cambridge). Both were steadily employed up until the beginning of the fifties, when they slowly made successful transitions into TV. For Paul Cavanagh one of his earliest TV jobs was as a recurring character, Colonel Henderson, on the children’s show Space Patrol (1950). He also appeared in the SF-ish Port Sinister (1953, review), The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957, review) and She Devil (1957, review).

The most sympathetic character in Son of Dr. Jekyll is Jekyll’s butler Michaels, who gets a heroic turn at the climax of the film. Less jovial than in most of his roles, Rhys Williams plays the caring butler with real warmth, and one does feel a bit sorry for the old chap. While often playing Irish characters, Williams was in fact Welsh, and had a background as a respected stage actor in Britain, even with a spell at the legendary Globe Theatre. His Hollywood debut came about when he served as Welsh language coach on John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley (1941), and Ford subsequently cast him in one of the roles. Michaels appeared in close to 150 films or TV series in his movie career, although his SF involvement was almost exclusively confined to guest spots on TV.

The guy you see leaping rooftops, crashing through windows and falling to his death (twice) in Son of Dr. Jekyll is legendary stuntman and later stunt coordinator Paul Baxley. Baxley is best known for his work as stunt coordinator on the original Star Trek series (1967-1969), where he had the distinction of being William Shatner’s stunt double. During his career he also doubled for Marlon Brando and James Dean, among others. Baxley was also a stuntman on Atlantis: The Lost Continent (1961) and was a stunt coordinator on the show Wonder Woman (1975-1979). In the nineties he coordinated stunts on a string of SF B movies: Dolph Lundgren’s Dark Angel (1990), Class of 1999 (1990), Timebomb (1991), starring Terminator star Michael Biehn and Deep Red (1994), directed by his son Craig R. Baxley. Paul Baxley also worked as a second unit director on action sequences and directed a number of TV episodes. His son, nephew, grandson and great-grandson are all stuntmen and stunt coordinators, with Craig racking up quite an impressive directorial resumé as well, primarily TV movies.

Editor Gene Havlick had won an Oscar for his work on Lost Horizon (1937), and was nominated twice more. Born in Paris, France (where else?), Jean Louis was one of the most sought-after costume designers of Hollywood, with a dozen Academy Award nominations and one win to his name. Makeup artist Clay Campbell had previously made up Boris Karloff for the Columbia SF horrors The Man They Could Not Hang (1939, review) and Before I Hang (1940, review). He also worked on KIller Ape (1953) , The Werewolf (1956, review) and The 30 Foot Bride of Candy Rock (1959). Campbell was noticed by Perc Westmore, the head of Warner’s makeup department, when he was commissioned to make wax puppets for The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), and was hired, but eventually ended up at Columbia, where he became their head of makeup. Campbell is responsible for the werewolf makeup that debuted in Return of the Vampire (1943), popped up in the Three Stooges short Idle Roomers (1944) and was later perfected for The Werewolf. In my opinion, it trumps the iconic Lon Chaney-look from Universal’s Wolf Man films, which I have never been particularly fond of.

Janne Wass

Son of Dr. Jekyll. 1951, USA. Directed by Seymour Friedman. Written by Jack Pollexfen, Mortimer Braus, Edward Huebsch. Inspired by the novella The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. Starring: Louis Hayward, Jody Lawrance, Alexander Knox, Lester Matthews, Gavin Muir, Paul Cavanagh, Rhys Williams, Claire Carleton, Doris Lloyd, Patrick O’Moore. Paul Sawtell, Paul Mertz. Cinematography: Henry Freulich. Editing: Gene Havlick. Art direction: Walter Holscher. Gowns: Jean Louis. Makeup: Clay Campbell. Sound engineer: Jack A. Goodrich. Stunts: Paul Baxley. Produced for Columbia Pictures.

Leave a comment