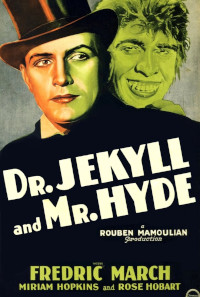

(8/10) By many considered as the best version of Stevenson’s classic book, this 1931 film resulted in an Oscar win for actor Fredric March. Beautifully filmed by Rouben Mamoulian and well acted across the board. It also features some stunning visual tricks and strong pre-Code sexual content.

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 1931, USA. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian. Starring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart. Written by Samuel Hoffenstein, Percy Heath. Based on plays by Thomas Russell Sullivan, Luella Forepaugh, George F. Fish, based on novel by Robert Louis Stevenson. Produced by Rouben Mamoulian, Adolph Zukor. Tomatometer: 93. IMDb score: 7.7. Metascore: N/A.

The Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde story is one of the most enduring and classic ones in both literature and film history. Although the motives and circumstances of for splitting one character into two have changed from adaptation to adaptation, the basic premise of the story is still compelling. This 1931 version is the first sound film, and like most films, it is an adaptation of two 1887 stages play by Thomas Russell Sullivan, Luella Forepaugh and George F. Fish, rather than the book by Robert Louis Stevenson.

I have already written extensively about Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and for a more detailed look on the evolution of the story, please read the reviews of the different film adaptations from 1912, 1913, and most importantly, 1920.

There is an ongoing debate among film buffs about whether the 1920 or the 1931 version is the ultimate one (while the 1941 adaptation with Spencer Tracy [review] is mostly regarded as inferior). I am personally partial to John Barrymore’s portrayal of Hyde in the 1920 adaptation, and its strong influences from German expressionism, but Fredric March’s work in this film has slowly grown on me over the years, and cinematographically the 1931 adaptation is simply a better film. Then again, one must take into account the huge technical advancements in film between 1920 and 1931, as well as the added benefit of sound, for making a more complex story.

The starting point of this film is physician Dr. Henry Jekyll (March) and his fiancee Muriel Carew (Rose Hobart). Her father Danvers Carew (Halliwell Hobbes) won’t give the lovers permission to marry before the anniversary of his own marriage – and of course according to Victorian morals this means there will be no rolling around in the hay before the knot has been tied. Henry Jekyll, though, really, really wants to dip the tip and throws a fit when he’s told he has to wait another eight months. During a stroll home from a dinner party at the Carews Jekyll remarks to his colleague Dr John Lanyon (Holmes Herbert) that ultimately a thirsting man must have water, regardless of who it is that offers it, which is thirties speak for “I’ll soon fuck anything that moves”. In Jekyll’s case the offering comes the same night from a bar singer, Ivy Pearson (a wonderfully seductive Miriam Hopkins) in a sexually dripping scene where there is a flash of underboob and a naked, dangling leg filling the screen – outrageous at the time. While Jekyll, though tempted, kindly rejects the offer, it won’t be long before his darker self seeks out the lurid Ms. Pearson …

In the novel Jekyll had no love interest, but the 1931 adaptation actually follows the book inasmuch as it doesn’t portray Jekyll as a saintly figure, as the stage plays did. Instead, Jekyll is presented as a man who regularly upsets the codes of intellectual society, proposing theories that are deemed immoral and blasphemous. While it’s only hinted at, we are given the idea that this streak of “immorality” applies to his social life as well, which apparently is one of the reasons that Mr. Carew is loath to give up his daughter’s hand in marriage to him. Indeed, in his discussion home from the party, Jekyll explains to Lanyon that a man shouldn’t fight his natural instincts, but give in to them.

However, and this is where things get a little muddled, as they always tend to do in the Jekyll/Hyde films, this really has nothing to do with Jekyll creating his formula, as it did in the book. The problem plaguing all early film adaptations is the fact that they were based on the popular stage plays, which were both adapted into religiously acceptable moral tales, in order to avoid too much criticism from conservatives. In the book, Jekyll’s potion is created with the single purpose of changing his exterior so that he can go about getting drunk and visiting prostitutes without tarnishing his good name. Of course, as time goes on, his dark side, connected with the Hyde persona he has created for himself, becomes ever more dominant, until it finally becomes something of a split-personality and takes on a life of its own. It is the stage plays that introduce the idea that Jekyll wants to “split the good and evil in man”. And this has carried on to all the three classic film adaptations.

The 1931 film opens with Jekyll giving a fiery speech before his scientific colleagues, in which he proposes the idea that in the future one could get rid of one’s dark side through splitting the personality in one good and one evil persona – and in the dark side the evil of the soul would ultimately spend itself until only good remains. And unfettered by the darkness in our souls, the good will rise to ever higher elevation, Jekyll explains. What all three film adaptations conveniently forget to mention is that, by the same logic, the evil side will sink ever lower depths.

The plot then more or less follows the same path as the 1920, 1913 and 1912 versions. Jekyll creates his potion in his lab, drinks it, becomes Hyde and goes off to a bar/music hall, causing a ruckus. In the 1920 version he also picks up a dancer, who is of little consequence to the story, and in both the 1931 and the 1941 version, this woman is Ivy Pearson/Peterson, who has previously flirted with Dr. Jekyll. What this film does bring to the table, though, are the scenes of Mr. Hyde raping and abusing Ivy Pearson, the bar singer, both mentally and physically. After essentially kidnapping her, he sets up Pearson in a luxurious flat, where he visits her almost daily in order to have sex with her, and abuse her in a number of ways. Pearson is essentially a creation of the screen writers Percy Heath and Samuel Hoffstein, even if there is a prostitute that Hyde frequently visits in the book.

Jekyll turns into Hyde repeatedly over the course of a month during Muriel Carew’s absence from London. When he is finally confronted by all her unanswered letters at the end of the month, and remembers all the ill deeds he has done as Hyde, he decides to stop the experiment, and sends Pearson 50 dollars as compensation for his bad deeds, for her to be able to leave London and start a new life. Jekyll also throws away the key to the back door to his lab, which Hyde has been using in order to get unnoticed past the butler. However, he later transforms into Hyde without the potion, and kills Pearson as Hyde.

Needing to quickly change back into Jekyll, Hyde now realises that he can no longer get into Jekyll’s lab. That’s when he seeks the help of his friend Lanyon, who has previously warned him about his immoral and indecent attitude toward science and life in general. Threatening Lanyon, Hyde uses his lab to create the potion, and by drinking his antidote turns back into Jekyll before his friends eyes. Lanyon scalds him, and refuses to help him, but promises not to spill his secret.

Full of regret and despair, Jekyll visits Muriel and asks her to forgive him for his transgressions, without telling her exactly what he has done. He explains that he must give up Muriel for his sins, and because he loves her too much to harm her. Muriel refuses, but Jekyll leaves her nonetheless. But just as he is on his way out, he changes again, and returns and tries to attack his fiancee. Luckily he is stopped by Lanyon and Mr. Carew, who chase him through the streets of London, with the aid of the police. The chase ends at his lab, where he manages to turn himself back into Jekyll before the police break down the door. However, Dr. Lanyon points out Dr. Jekyll as the culprit, and when confronted Jekyll starts to transform again. This leads to a dramatic fight at the lab, with a dozen police officers trying to catch the nimble, ape-like Hyde who climbs up cupboards and throws lab equipment at the bobbies. When he pulls a knife, one of the policemen shoot him, and as he dies, he again turns into Jekyll — note that this is the first film version on which he doesn’t take his own life.

Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was Paramount’s answer to the popularity of Universal’s horror movies Dracula and Frankenstein (review), both released earlier the same year. The movie’s premiere was on New Year’s Eve 1931, and it opened to the general public on January 2, 1932, and that’s why different sources name it as either released in 1931 or 1932. The Criterion Collection Blu-Ray/DVD lists it as a 1932 film, while IMDb has it filed under 1931. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was one of the few classic horror stories that Universal never got their hands on, since other studios owned the rights. (That didn’t prevent them from borrowing the premise in a number of films, though.) Initially John Barrymore was asked to reprise his role, but he was busy. March was probably greenlit for the dual role by the studio after some grumbling, because of his strong resemblance to Barrymore, although he completely made it his own.

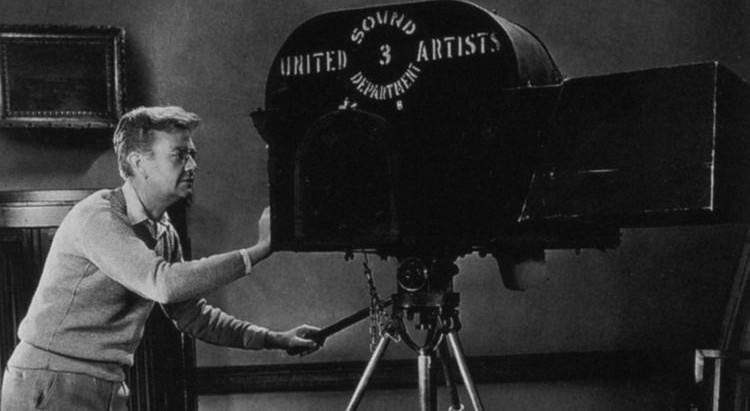

As stated the film was adapted from the theatrical tradition, mainly one “authorised” version by Thomas Russell Sullivan, and one “unauthorised” version by Luella Forepaugh and George F. Fish. The 1931 film adaptation was done by screenwriters Percy Heath and Russian emigre Samuel Hoffenstein. The latter would later contribute to such classics as The Miracle Man (1932), The Wizard of Oz (1939) and The Phantom of the Opera (1943). As director was chosen the Armenian-Georgian Rouben Mamoulian (who also produced), one of the most talked-about directors in Hollywood after his groundbreaking sound film Applause, made in 1929. Applause was one of the first movies to free up the use of the camera after it had been confined once again to mainly static shots because of the restrictions put on filmmaking with the introduction of the talkies.

As with Frankenstein, the version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde presented on the screen in 1931 bears rather little resemblance to the source novel, partly because both are based on stage plays that took very generous liberties with the source material. However, the Frankenstein story has since been reworked numerous times over, sometimes with the intention of presenting the audience with a film that does the book justice. Even the author Mary Shelley’s life has been put to film a number of times, and the general public tend, to the extent that they care about such tings, to be aware of many of the discrepancies between novel and film. This is not the case with The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Here, the story presented in the three classic film adaptations is mostly taken for granted as the definitive version, despite the fact that most of the plot is nowhere to be found in the actual novel.

One of the reasons for this is that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is considered as one of the masterpieces of world literature, and is thus more widely read and analysed. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is considered a classic and still widely read, but I would think that on the whole, far less people who watch the films have opened the book. Another reason I suspect is that there haven’t really been any mainstream adaptations that have tried to present the story as it was written. The closest we get to this is probably the CBC’s Canadian 1968 TV movie starring Jack Palance. In recent years there has been a few very low-budget indie attempts to bring the novel to life, including one very obscure entry from 2008 and one directed by B. Luciano Barsuglia in 2017, that made a bit of a splash in indie festival circles.

Of course the problem with doing a straight literary adaptation is that the book is written as a mystery thriller from the point of view of a Mr. Utterson, who’s erased in most film adaptations. Utterson is the “detective” of the novel, which opens with the suicide of Henry Jekyll. The story is then told in an epistolary flashback fashion, leading up to the big reveal at the end, that Jekyll and Hyde were indeed the same person. The novel came out in 1886, at a time when detective stories were becoming increasingly popular — in fact a year before Arthur Conan Doyle published his first Sherlock Holmes story A Study in Scarlet. By the time he wrote it, Stevenson was already famous for his adventure novel The Treasure Island, but also for a number gothic or macabre short works, such as The Body Snatcher, Thrawn Janet, The Merry Men, Markheim and Olalla, as well as the collection fix-up The Suicide Club. And when The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde hit the shops, it immediately became an international best-seller. And already in 1887, when the first stage adaptations were made, most people already knew the gimmick of the story — that Jekyll created a potion to turn himself into the evil Mr. Hyde. So any adaptation couldn’t use that as a dramatic punch-line.

Furthermore, it’s always been difficult to adapt epistolary stories for the stage. Even when Frankenstein is “faithfully” adapted, it’s usually adapted as a linear story, perhaps within a frame. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is nigh unadaptable for a modern audience without making some kind of alterations or additions to the story, as very little actually happens in the book. There is no love story, no great scheme to separate the good and evil in man, no falling-out between colleagues. There’s just the respectable Dr. Jekyll going about his business, and then sometimes disappearing for weeks in end, and at the other end Mr. Hyde rampaging through London. The only real contact between the two characters is that Hyde beats to death one of Jekyll’s clients, Sir Danvers Carew. But while he is turned into the father of Jekyll’s fiancee in the films, he is a wholly inconsequential character in the book, barely mentioned other than in connection with his death. The other sole connection is that in the novel, Hyde actually seeks out Lanyon when his own supply of ingredients have run dry, and transforms himself in the presence of Lanyon, which leads to Lanyon having a mental collapse and ultimately withering away. Other things that happen whilst Jekyll is transformed into Hyde is mostly alluded to, as it was far too lewd to spell out in 1886, and would have been even more unthinkable to show in a film in the thirties — even a pre-code film.

So the playwrights of the late 19th century instead made the transformations into the draw of the play, added a fairly mundane romance fired off the moralistic guns on all barrels. Borrowing from Frankenstein, they made Jekyll a moral man whose quest to rid the world of evil backfires when he “meddled with things than man should leave alone”.

The one thing that bothers me with all the famous film adaptations is the complete lack of logic of the central premise. Now, I can buy ideas of making potions that splits a man’s personality, I can buy notions of electric monsters and telepathic brains living in vats — as long as the scripts don’t ask me to buy into flawed logic at the heart of the premise. If a scientists says he’s created a potion that splits the good and evil in man — fine! Leave it there! But the problem is that both the plays and the films present a scenario where the evil part is completely overlooked. The 1920 version is most egregious in this affect, as Jekyll proposes that a man can cleanse his soul from evil by locking it away in “another body”, leaving only the good in himself. Hrrm, Mr. Genius Scientist: NEWSFLASH! THE EVIL PART IS STILL ATTACHED TO THE SAME BODY! Just because it changes appearance, doesn’t mean that it disappears into thin air, which is basically the argument that is made in all these three films. This is such a stupid premise that a five-year old can point its flaw. It doesn’t really take away from the film, but it’s just one of those things that keeps bugging me, especially as it could have been avoided had they just stuck a little closer to the novel.

This said, the 1931 script is in many ways a better and more engaging adaptation than the 1920 version, owing partly to the fact that it is a talkie, and thus can get across more nuanced dialogue. Most effective of the additions are the scenes with Evy Pearson and Hyde, which are really hard to watch in their psychological brutality even today. What’s basically shown on screen is a man dominating his kidnapped sex slave. In comparison, the romantic part of the script is handled much less aptly, and the romantic scenes between Jekyll and Muriel are painfully banal and clumsy. The death of Ivy Pearson is a harrowing moment, as she is by far the most likeable character in the movie. We don’t really care about Muriel, despite the fact that she has a couple of strong moments early in the script. She’s just too bland a “good girl”, as was so often the case with the female leads in these kind of films.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde also features some stunning camera work, including impressive crane shots, tracking shots and wild camera spins, most notably during Jekyll’s first transformation, when the whole rooms spins around several times. The sort of focus-pulling that goes on in the shot shouldn’t have been possible with a camera spinning on its own axle, not at that speed, as someone had to have their hands on the lens, pulling the focus. But impossible was not a word in director Rouben Mamoulian’s vocabulary. Solution: he took the smallest camera technician he could find, strapped the poor fella to the top of the camera, and sent both camera and man spinning.

All in all, the film feels very modern in its visual language, as if unhampered by many of the technical difficulties of the time.

The opening scene sets the tone immediately, as the camera follows a continuous POV-presentation of Dr. Jekyll, starting with his hands as he is playing the organ, Phantom of the Opera-style, to him getting disturbed by his butler telling him it’s time for his address at the Royal Society. We watch as he walks down the hall, and in a clever shot sees himself in the mirror (we all know how the trick is done, but it’s a nice touch nonetheless). Walking through his front door, he takes his place in a horse-pulled cab and we see him drive through London, to the Royal Society, where he is greeted by the guards and finally we see his point of view as he walks into the grand hall, filled to the brim with spectators. Only then does the camera turn around and reveal the man himself. While this would be seen as a cliched opening today, one must remember that in 1931 film-goers had gotten used to the fact that talkies were dully filmed and static, because directors were frozen in terror over sound. For this there were two main reasons. The first was that they needed to make sure that the actors were near a microphone when they said their lines, as early microphone had very limited range. The second was that cameras suddenly became very large, bulky and heavy: early film cameras were extremely loud, and had to be muffled with big, insulated boxes, making them even more cumbersome to move around than before.

The most impressive visual trick of the film is the transformation. In the first scene we see the make-up revealed gradually on March’s face in one single, unbroken shot, changing from Jekyll to Hyde. The scene is still astounding today, and would paradoxically not work today with all our computer generated images. Here Mamoulian could draw on one of the benefits of black and white cinema – the absence of colour. Paramount kept the key to this scene a secret for many years, but the director eventually cracked (and of course, a lot of people had already guessed how it was done). Nevertheless, I still see many normally reputable sources claim that the sequence was done with the aid of coloured lens filters. This is, of course, impossible, as they wouldn’t be able to change filters in front of the camera without it showing up in the picture — or editing. In reality is was done by the aid of tinted studio lights. Makeup artist Wally Westmore would first paint the makeup on March’s face in different hues of red. When the studio lights were switched to red, the makeup disappeared. Then by slowly dimming the red light and fading in blue light, the lines in March’s face gradually start appearing, first as faint grey and later black. A really simple trick, but marvellously executed. Mamoulian also used a couple of very well edited replacement shots to add the hair on March’s hands and the canine teeth and neanderthal/ape man appearance of Hyde.

It should be pointed out that the neat trick with the seamlessly appearing makeup probably wasn’t Mamoulian’s idea, but cinematographer Karl Struss’. Struss had used a similar technique in the silent version of Ben-Hur (1924). Karl Struss, was a Hollywood legend, known for masterpieces like F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. But he also moved about genre cinema. In 1932 he shot the H.G. Wells adaptation Island of Lost Souls (review), another Paramount production that rivalled, if not surpassed Universal’s horror movies. He also filmed Rocketship X-M in 1950, the alien computer film Kronos (review) in 1957 and the sci-fi classic The Fly in 1958.

While Wally Westmore’s makeup for Hyde rivals anything that Jack Pierce did over at Universal at the time, I’ve always been a bit effy about the design. The novel suggests rather than says what Hyde looks like, with a passing mention that he is “hideous”. Early adaptations, starting with the 1887 stage performances, gave him an ape-like, stooped gait and sometimes took this to the absurd, having the actor walk around folded down over himself three times, as in the 1913 King Baggott adaptation. What makes John Barrymore’s Hyde stand out is that he completely reinvented Hyde, as more of a spidery Svengali character. Mamoulian, on the other side, probably wanted to subvert the Barrymore image of Hyde, chose to portray how Jekyll reverted to his most basic instincts — in fact to his neanderthal brain, inadvertently, perhaps, returning the sometimes unintentionally comic portrayals of the pre-Barrymore movies. My main problem with the design is that Hyde, while creepy, should still be able to pass for a normal human being in society. In Westmore’s makeup he looks like an ape. And at least they could have spared us those hideous false teeth.

The rest was up to March, who plays Hyde with such joy that it is impossible not to feel for the man. ”Im free!” shouts Hyde when he first looks himself in the mirror. As Lyz Kingsley writes at And You Call Yourself a Scientist: “In truth, the real audacity of Mamoulian’s concept of Hyde lies less in its design than it does in its execution, particularly during Jekyll’s first two transformations. The Hyde we become acquainted with at first is, well, rather a jolly chap. The exuberant physicality of March’s performance here gives us one of the screen’s most unusual interpretations of Hyde. He is delighted to be here, delighted to be “free at last”, delighted with everything. He laughs and runs and stretches, feeling his existence; most famously, as he steps out into the rainy night, he sweeps off his hat and lifts his face to the sky, allowing the rain to fall onto his face and hair, and enjoying the sensation immensely. If we are already well-acquainted with Henry Jekyll’s ego, here we meet his id.”

Mike Sutton at The Digital Fix also comments on the use of sound in the film — and one thing that I think I have never even reflected on when seeing the movie is that it has almost no music: “The director is equally daring with his use of sound. It was a convention at the time that one should only have one microphone and one channel. Mamoulian defies this by having a scene in which Jekyll and Muriel talk while, in the background, we hear the sound of an orchestra playing through an open door. The use of heartbeats on the soundtrack is another effective touch which has since become a cliche but was first attempted here.” The heartbeats used in the first transformation sequence were actually Mamoulian’s own, recorded after him having run up and down a flight of stairs.

The strong sexual content is another thing that makes this film memorable. It was severely hacked up by the sensors at its re-release in 1936, after the Hays Code had been enforced, and it would take decades before cinema was again allowed to portray sexuality so openly. In 1931 the Production Code did exist, but as it had no actual reinforcing body, it was, to paraphrase and old zombie pirate, “more guidelines than actual rules”. The code restricted the depiction of things like drugs, alcohol, violence and, most importantly, sex. But if played right, filmmakers could get away even with some nudity, even if full frontal was out of the question (this wasn’t Europe, after all). However, Mamoulian’s film suggests a lot more than it spells out, and the suggestions are both lewd and tantalising, and later horrific. These kinds of suggestions would never have passed the Hays Code after it’s reinforcement in 1934. And, as stated, they didn’t.

To make matters worse for this film, when MGM bought the rights to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde for their 1941 adaptation, they buried the 1931 movie in their vaults and refused to show it, so that no-one could make comparisons between the 1931 and the 1941 film. When re-released again on TV, it was the mutilated Hays Code edit. It wasn’t until 1989 that the almost complete original edit was shown. The wonderful Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant writes: “The film is heavy on visual allusions and refreshingly light on moral judgments. Erotic statues and paintings comment on Hyde’s sexual domination of Ivy, and Jekyll is confronted with images of skeletons and fiery cauldrons. The visuals relate the story to other pre-Freudian literary examinations of split personalities and psychotic enigmas, such as The Picture of Dorian Gray. It’s hard to find horror films as good as this one.”

The actors are all good, although it is March and Hopkins as Ivy that shine in this film. Fredric March was a surprise choice after John Barrymore had declined, especially for Paramount. While Universal happily promoted unknown actors in their monster films, Universal was a struggling mid-tier studio that couldn’t afford Paramount’s stars. Paramount, on the other hand, was the star studio, that worked from the idea that the stars carried the films, and things like scripts and directors were secondary. At the time, Fredric March wasn’t a movie star. Kingsley writes:

“His mind on Hyde, [producer Adolph] Zukor offered Mamoulian screen heavy after screen heavy; Mamoulian rejected them all, arguing that he wanted someone who could play Jekyll – and insisting upon the signing of Fredric March, at the time known best as a pretty boy secondary lead and a light comedian.

March’s casting in the dual roles of Jekyll and Hyde was one attended by a good deal of irony. When John Barrymore had briefly stepped aside from his stage career to appear on film as horror’s most famous split personality, he had been motivated not just by the acting challenge involved, but by a desire to break away from too many bloodless acting roles that required little more of him than to stand there and be handsome. This was a fate that Fredric March was destined to suffer also. Although March had played bit parts in film all the way through the twenties, his real success was as a stage actor. His permanent move to motion pictures came as a result, oddly enough, of the rave reviews that he won with his performance in The Royal Family Of Broadway, a comedy loosely based upon the Barrymores themselves, in which March was the play’s “John”, Tony Cavendish; his first major film success would be a reprise of his stage triumph. However, the praise March won in the early phase of his new career wasn’t quite what he wanted: when the critics started calling him “the new John Barrymore”, they weren’t referring to his acting abilities; they were talking about his profile. Even as early as 1931, Fredric March was sick of it, and looking for a way of proving that he was more than just a pretty face. Rouben Mamoulian’s offer of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde was a professional godsend.”

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was a tremendous success for Paramount, and prompted another well-produced horror film in 1932, The H.G. Wells adaptation The Island of Lost Souls, starring the great Charles Laughton. But the studio ultimately didn’t take up the fight over horror supremacy with Universal, and was content release a couple of by-the-books B-movies of the old dark house variety in 1933 and 1934, before more or less abandoning the genre for the rest of the decade. And as horror films and serials the only genres in which science fiction appeared in Hollywood, basically throughout the thirties and forties, this meant that Paramount also gave up on sci-fi, with a few exceptions along the way, until the fifties.

It’s a shame that Paramount didn’t do more of these, as both Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and Island of Lost Souls were extremely good horror/sci-fi films. While James Whale and a couple of other director directors did outstanding work over at Universal, there’s a sort of class to the Paramount features that Universal never achieved. With Universal it was always a bit tongue-in-cheek, even in its darkest moments, owing primarily to the legacy of Whale, who loved the camp and the morbid humour that the horrors gave him permission to do. But Paramount played it straight in both or their flagship horror films, and stuff doesn’t really get darker and creepier than they did in Island of Lost Souls, that’s one of the few thirties horror films that remain thoroughly scary even to this day — if not indeed the only one.

But on the other hand — while Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde can be said to be a better film than most of Universal’s sci-fi/monster movies (excluding Bride of Frankenstein [1935, review]) from a perspective of camera handling, special effects, screenwriting, acting and overall direction, I somehow can’t find it in me to love the film — not in the same way that I love the first two Frankenstein movies, The Mummy or The Invisible Man (review) — and certainly not in the way I love the old German expressionist horrors, or even the 1920 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde version. For all its brilliant camera work, its visual tricks, great acting and wonderful atmosphere (someone said the best vision of Victorian London brought to screen in the thirties), there’s something lacking in the film, which I for lack of a better word would call: soul. I’m not sure exactly what it is that ails me with this film, but it just doesn’t fire me up in the same way as some of the other thirties horror classics do: perhaps it’s the fact that it takes itself a bit too seriously. Some of you may disagree, and this may simply be chalked up to the fact that the Universal films and the German films were my introduction to the old horror movies, and I have spent s much time re-watching and researching them that I feel that they are old friends of mine. Perhaps it’s that the romantic scenes between March and Hobart are so dreadfully badly written and, as Richard Sheib writes at Moria: “wretchedly over the top in their tortured banality”. Whatever the case, this results in me not giving this film more than 8/10 stars, thus ranking it lower than, for example, Frankenstein.

Some trivia: this is probably the only mainstream film adaptation in which Dr. Jekyll’s name is pronounced correctly, that is with a long e, like in feeling or reason: “Jeekyll”, which was how Stevenson insisted it should be pronounced.

Anyhow, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde made Fredric March an overnight sensation in Hollywood. He famously won the Academy Award for Best Actor, a feat that has been repeated only three times for a science fiction film since: twice when the film was a sappy melodrama (although Charly was a very good film) and the last time when the actor died (Heath Ledger as the Joker). The film was also nominated for best adapted screenplay and best cinematography. In addition, March took home the audience award for best actor at the Venice Film Festival, and the film’s screenplay was voted as the best one in the fantasy category.

Fredric March went on to win a second Oscar for The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and was further nominated three times: The Royal Family of Broadway (1931), A Star is Born (1938), and lastly for Death of a Salesman (1951), for which he won a Golden Globe and the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival. He won the Silver Bear at Cannes for his work in Inherit the Wind (1960) as well as the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival as part of the ensemble cast in Executive Suite (1954). He was nominated thrice for a Golden Globe, thrice for a BAFTA and twice for an Emmy. While March made fun of Spencer Tracy’s performance in the 1941 adaptation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, joking that it was so bad that it made his own seem even better in comparison, Tracy had the last laugh when he co-starred in Inherit the Wind, and was nominated for an Academy Award, whilst March was snubbed.

Rose Hobart partly falls under the peculiar curse of the leading woman, that in so many old films are the most uninteresting characters on screen, confined to longing, pouting and occasional screaming. That said, this film does give her a little more character than most of her horror movie ingenue sisters. Especially the beginning of the film promises more than is ultimately delivered, as she is seen defending Jekyll, and even sneaks out to the garden during the dinner party for some passionate kissing, even while giggling: “My father would be furious!” Ultimately, though, Muriel concedes to her father’s will, not that she necessarily would have had any choice in the matter. Hobart also gives a strong performance towards the end of the movie, as she tries to console the hysterical Jekyll when he tries to push her away from him. All in all Ironically this was one of Hobart’s few leading lady roles.

They were more often given to Miriam Hopkins, a very popular actress during the thirties and early forties, often in quite risqué roles, such as a rape scene in The Story of Temple Drake (1933) and a ménage à trois with Fredric March and Gary Cooper in Design for a Living the same year. She was nominated for an Oscar in the title role of Becky Sharp in 1935. Hopkins was an actor who liked to go out on a limb and take risks in her films, and this was also when she was usually at her best. She continued to act through the thirties and the forties, but most of her memorable work was done during the pre-Code era, when her intense acting sensibilities could still be harnessed to their fullest. In 1947 she took short a break from Hollywood, but her comeback film in 1949, The Heiress, garnered her a Golden Globe nomination, and she continued to act in both film and TV all up until 1970. Known for her temperament, Hopkins had a long-lasting feud with Bette Davis, competing for roles both on Broadway and in Hollywood, and sometimes even for men. In 1934 Hopkins turned down the lead in It Happened One Night, as she felt it was “just a silly comedy”. The role gave Claudette Colbert an Oscar win. Hopkins was portrayed (briefly) by Sheila Wells in the 1980 film The Scarlett O’Hara War.

Holmes Herbert was a theatrical actor who started in silent films with stalwart leading roles, and had supporting roles in many classic Hollywood films of the sound era, including Captain Blood (1935), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), The Life of Emile Zola (1937), and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). He also became a staple in horror B-films of the era, like The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), The Invisible Man (1933), Mark of the Vampire (1935), Tower of London (1939), The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942, review), The Undying Monster (1942), The Mummy’s Curse and The Son of Dr. Jekyll (1951, review).

Halliwell Hobbes was a distinguished actor who also started appearing in lesser B-movies on the flipside of his career. In 1936 he had a role in Dracula’s Daughter, he joined Herbert in The Undying Monster, and appeared in The Revenge of the Invisible Man in 1947. Tempe Pigott as Mrs Hawkins appeared in uncredited supporting roles in The Bride of Frankenstein and Werewolf of London in 1935. Edgar Norton (as Poole) appeared alongside Hobbes in Dracula’s Daughter and had a supporting role in Son of Dracula in 1939.

Janne Wass

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 1931, USA. Directed by Rouben Mamoulian. Starring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart, Holmes Herbert, Halliwell Hobbes, Edgar Norton, Temple Pigott. Written by Samuel Hoffenstein, Percy Heath. Based on the play by Thomas Russell Sullivan (uncredited), based on the novel Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stephenson. Cinematography: Karl Struss. Art direction: Hans Dreier. Makeup: Norbert A. Myles, Wally Westmore. Editing: William Shea. Produced by Rouben Mamoulian, Adolph Zukor for Paramount.

Leave a comment