This 1956 SF thriller directed by Don Siegel is a masterpiece dissecting American post-war paranoia and timeless themes of losing one’s identity and sense of belonging. One of the few fifties horror films that is still spine–chilling today. 10/10

Invasion of the Body Snatchers. 1956, USA. Directed by Don Siegel. Written by Daniel Mainwaring, Richard Collins. Based on novel by Jack Finney. Starring: Kevin McCarthy, Dana Wynter, King Donovan, Carolyn Jones, Larry Gates, Virginia Christine, Jean Willes, Whit Bissell. Produced by Walter Wagner & Walter Mirisch. IMDb: 7.7/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 9.1/10. Metacritic: 92/100.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers begins with one of the most famous framing devices of movie history. A psychiatrist is called into a hospital room to calm a seemingly deranged man, who identifies himself as a Dr. Miles Bennell, and insists he is not crazy, and that people have got to listen to him, because they are all in danger. After calming down he begins his story …

Drenched in the deep barytone of Dr. Bennell’s initial voice-over, the movie rolls out a tale that has since been duplicated both officially and unofficially for decades. Dr. Bennell, a small-town doctor (Kevin McCarthy) has been called back from a conference by his old flame, Becky Driscoll (Dana Wynter) because she is worried about her cousin, who seems to suffering from some strange mental illness — she is convinced that her uncle, with whom she lives, is not her uncle, but has been replaced with a duplicate. Bennell initially writes it off as a delusion, but more and more cases of people who are convinced that their loved ones have been replaced by impostors keep cropping up. Rekindling the old flame, Bennell and Driscoll round up their strange day by going to the local watering hole, only to find it near empty of people, despite it being Saturday night. The maitre d’ tells them it’s usually packed, but now, for some reason, people aren’t showing up. Before they have the time to get the night on, Bennell is phoned up by his old friend Jack Belicec (King Donovan) who needs Bennell to come to his house right away.

At the house, Bennell and Driscoll are greeted by Belicec and his wife Teddy (Carolyn Jones), who are beside themselves because of a strange body that has appeared out of nowhere in their basement (and now lying on their pool table). It seems, notes Bennell, as if its features were not fully formed — but as Teddy points out, frightened out of her mind, it looks almost exactly like her husband Jack.

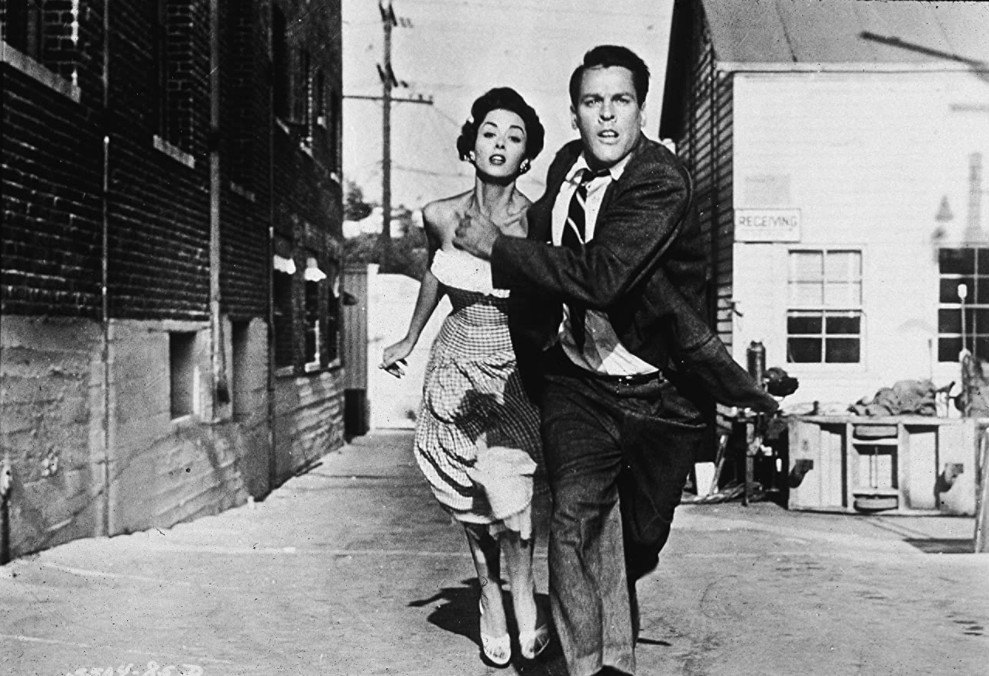

I’m not going to get too deep into the plot with this movie, because if you haven’t seen it, you’ll want to watch it unfold for yourself. But in short, Bennell, Driscoll and the Belicecs realise that someone or something is bringing in giant seed pods to the town of Santa Mira, that duplicate people while they are sleeping. The duplicates, which they label “pod people”, retain the memories and characteristics of the people they are imitating, however they are devoid of feeling and live only to serve the procreation of their race. They blend into the small town for as long as they need to duplicate all its inhabitants, and plan on using it as a base for taking over all of the US and finally the world. As Bennell and Driscoll find and kill their own half-formed duplicates born out of a pair of seeds in Bennell’s back yard, the realise it is a fight against time, and above all, sleep, as they wait for the Belicecs, who have tried to get out of town to get help. As morning dawns, they are holed up at Bennell’s clinic, watching the entire town turned to single-minded zombies. I won’t reveal though, how we end up at the film’s most memorable moment the next evening, with a crazed Bennell running among the headlights on the highway, dishevelled and hollow-eyed, shouting at the cars and the wind “YOU’RE ALL IN DANGER! THEY’RE HERE ALREADY! YOU’RE NEXT!” This would be a wonderful place to end the film, but there is that framing device, which leads us back to the hospital, where an offhand report picked up by the psychiatrist (Whit Bissell) turns the bleak open-ended finale into something more cheerful for the audience to take home.

A true fifties classic, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is one of the best films made during the decade, and one of the most iconic, superbly encapsulating the feverish paranoia of post-WWII America, as well as the great cultural shift of the fifties. Directed by the great Don Siegel, the film is based on the 1954 novel The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney. The script actually follows the book very faithfully. The first half of the movie is almost verbatim transferred to the screen, although the novel has a much more positive ending, with Becky and Miles setting fire to the pod fields with gasoline, and watch the remaining pods fly off into space. In the original story, all four of the main characters remain unduplicated, which is not the case in the film. Finney also wrote a clearer analogy between the pod race and the human race as a whole. In the book, the pods don’t just duplicate humans, but anything organic, like animals and plants, and are incapable of any other form of procreation. They only have a life-span of five years, which means that in time, they will have duplicated everything, leaving Earth a barren waste filled with pods. The pods will then leave, and search for the next planet to colonise. Observing the protagonists’ shock at this, the pod people counter that this is exactly what humans do: seek out new territory, kill its original inhabitants and usurp the natural resources.

According to film historian Bill Warren, the man we can ultimately thank for the film was producer Walter Wanger, who at the time was working for mid-tier studio Allied Artists. Wanger read Finney’s story when it was first serialised in Collier’s magazine in 1954, and was convinced it would make a great movie. However, the studio wasn’t sold in the idea, and Wanger had to fight for it. He succeeded, and was able team up once again with Don Siegel, for whom he had produced the tight, intelligent prison drama Riot in Cell Block 11 in 1954, named by Quentin Tarantino as “the best prison film ever made”. For the screenplay adaptation Wanger and Siegel hired novelist and screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring, who had worked with Siegel on the Robert Mitchum noir The Big Steal (1949) and the B programmer An Annapolis Story (1955). According to interviews with those involved, the original script included a lot more humour (as present in the book), and, crucially, did not feature the framing device. This is also how the movie was filmed. It was scheduled for release in late 1955, but the studio didn’t like the audience reactions at the first screenings. Exactly what they felt was wrong has never been definitely confirmed, but according to some testimonies, the studio heads felt that the audience laughed in the wrong places. Another point of view is that it was Allied Artists policy never to mix horror and comedy. So they ordered Siegel and editor Robert Elsen to remove the funny parts. But the studio also didn’t want the film to end with Dr. Bennell’s crazy rants on the highway. Again, it’s not exactly clear why. The popular notion is that AA felt the ending to be too down-beat, especially in the light of the fact that the original novel had a positive ending. But Bill Warren proposes that it could also be a case of “laughs in the wrong places”. Lead actor Kevin McCarthy chews the scenery in such a way in that climactic scene that the last shot of him screaming straight at the camera can elicit amusement rather than dread. Allied Artists also feared that the subject-matter at hand might make audiences and critics mistake the film for a silly flying saucer picture, and they were adamant that it should be perceived as the serious picture that it was intended as.

The original idea was to hire Orson Welles to read a prologue to the film. Welles had agreed, but he was off in Europe and was constantly moving about, and the AA producers could never pinpoint him long enough to send a crew to film the bit, and finally they just gave up. Instead AA decided to shoot the framing sequence and let McCarthy do some voice-over. Don Siegel hated the idea and initially refused to do the pick-up shooting. Wanger was also against it, but was overruled by the studio. According to Siegel, it was Wanger who convinced him to film the framing device, saying that if he wouldn’t do it, then they would find someone else who would. The framing device is regularly lambasted by fans and critics, but in all honesty, I don’t think that it takes away from the movie. It does change the feeling one has after seeing the film, which I think was probably why Siegel protested it so vehemently. The original ending was supposed to be grim, but the framing device turns it around, giving a hopeful note to the situation, as stern and effective government people assure the viewer that the US authorities will come through to save the day. It’s an unnecessary tack-on, but I don’t think it lessens the impact of the film.

Oftentimes, fifties SF movies would start with a smart and intelligent idea, but as the film progressed it would become dumbed-down and slowly disintegrate into schlock as the threat would be revealed as a clunky cardboard robot, lumbering aliens in baggy onesies or hammy mad scientists kidnapping babes in order to extract their vital fluids. Other times, producers didn’t trust the SF element to carry the movie, so padded it with an ill-conceived love story or trite melodrama. In a few, rare moments, Invasion of the Body Snatchers teeters on the point of tipping over into melodrama, but fortunately Siegel saves it by keeping the dialogue sparse and short. The main reason this film works so much better than most SF movies of the decade is probably that neither Siegel nor Wanger set out to make a “science fiction movie”, but rather a noir thriller with SF elements. The script isn’t without its flaws. Some of Mainwaring’s lines are admittedly a bit purple, and the voice-over threatens to evoke a bad Mike Hammer movie, but the story is so visually driven that a few errant lines don’t really hurt it. There is one glaring plot hole toward the end of the film, which has to do with the way in which the pod people take over your mind, but the moment is so emotionally charged, that I tend to forget about it every time I watch it, even though I know it’s all wrong.

Don Siegel has said that he wanted to give the film an almost documentary feel. Ellsworth Frederick’s crisp, matter-of-fact black-and-white cinematography in the beginning of the movie almost evokes an Italian neo-realist production, but as the story progresses, it descends further into film noir and expressionist horror movie territory with moody chiaroscuro lighting, bold camera angles and symbolism. As Miles and Becky flee from the mob at the end we are solidly in Frankenstein country. Before becoming a director, Don Siegel used to work for years at Warner’s stock film library, and eventually rose to the head of the studio’s montage department. This work certainly comes across in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, as tight, sure-handed, often rapid editing. Seigel never lingers longer than necessary on any single shot or scene, but the movie progresses at a brisk, almost frantic pace. So much happens during the 24 hours in which most of the film takes place that it threatens to fly past itself, but Siegel manages to keep it grounded even if the wheels sometimes threaten to come off the road in some of the tighter turns. The film is a masterclass in efficient storytelling — visual storytelling, but unfortunately the studio hasn’t had enough faith in the audience to follow along, and the voice-over, mostly superfluous, sometimes idiotic, lessens the impact.

Of course, the big discussion during the film’s almost 70-year history has been what it is really about. While all agree that it is rooted in the anxieties of the cold war and the changing social and psychological landscape of the US in the fifties, the interpretations of the movie are many and often contradictory. This is the main reason to the film’s staying popularity, and as to why it has aged so well. To use the words of JRR Tolkien: “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers.” An allegorical film would have made clear to the viewer that it was all about, say, the threat of communism in the US. And there is much in the film that supports such an interpretation. The popular idea in the West of communism as an ideology devoid of emotion, built on a repressive ethos of conformity and control, is easily applicable to the pod people. However, an equally popular interpretation is that the pod people represent Americans under the influence of the Eisenhower-McCarthy communist hunt. The US population was encouraged to spy on their neighbours and co-workers, and to report those who seemed “different” or “suspicious”. Thus, one can view Miles and Becky not as the free Americans falling prey to communism, but rather as the “outsiders” or “free thinkers” falling prey to McCarthyism. But it wasn’t just politics that were in the forefront of the US public debate (or lack thereof) in the mid-fifties. In the wake of WWII, economy was booming, a new middle class was rapidly outgrowing their small city apartments and moving into gated communities and white-picketed suburbs. Women who had taken over much of the menial work during WWI were now told that they they were free to back to being pretty housewives. The men, on the other hand, were supposed to work to support their families, go to church, be patriotic and friendly with their neighbours, take their kids to the ballgame, invest wisely, take an interest in politics, but not too much, and go out for a beer with their colleagues and discuss baseball and their family life. This petty bourgeois lifestyle with its cheery, carefree exterior was naturally not to the liking of everyone, and many felt that it brought with it a stifling conformity and the death of individuality.

Both Jack Finney and Don Siegel have denied that they intended any political allegory. The anti-colonialist message in Finney’s original book also lessens the cold war connection, that is more prevalent in the film. In interviews, Siegel has said stated “pod people” to him generally represented people who walk through life conforming to what is expected without questioning, and the rest of his life he kept referring to such as “pod people”. Siegel has said that he was certainly aware that one could read the film as McCarthyism allegory, but it wasn’t his intention to present it as such. In a 1985 TV interview with Tom Hatten, lead actor Kevin McCarthy explained that his interpretation of it was that it was the growing commercialisation and the advertisement industry that turned Americans into pod people. In this McCarthy shows a streak of Ray Bradbury’s thinking — Bradbury, whose novel Fahrenheit 451 was primarily a rumination on the effect of TV, advertisements and the non-stop entertainment industry on humanity. Leading lady Dana Wynters, for her part, tells film historian Tom Weaver that she was convinced from the start that they were making an “anti-ism” movie: “anti-ism; fascism, communism, all that sort of thing. We took it for granted that’s what we were making, but it wasn’t spoken about openly on the set or anything like that. These were delicate times, and I think that if Allied Artists had had the slightest idea that there was anything deeper to this film, that would hav quickly been stopped.” Of course, today there are certainly those who would draw parallels to so-called “PC culture” or “cancel culture”, while there is also a case to be made that the pod people could represent far-right internet trolls or, for that matter, electronic surveillance. If we abide by the author theory, the intention was probably not to make an anti-communism film. Screenwriter Daniel Mainwaring was a leftist sympathiser. It is sometimes claimed that he was blacklisted at one point during McCarthyism, but his wife has denied this. Rather, she said, he provided his name as a “front” for blacklisted screenwriters. As stated, what makes the movie so durable is that it isn’t a fixed allegory, but rather a story that within what might seem a rather straightforward (to modern eyes) SF cliché encompasses a rich wealth of thematic fodder.

At its core, if you strip it from its specific political interpretations, Invasion of the Body Snatchers deals with the breakdown of the social fabric surrounding us — either an external or an internal ripping of our psychological or social foundations. It deals with the fear of the very basics in life that we rely on for security, identity, love and meaning suddenly turning on us, becoming threats, or even worse, that we have always been deceived. It is that same primal fear that children have of monsters under their beds, or of waking in the night to find your loved one dead beside you. But it’s also a very real description of what it is like to not conform to the norms of society. This is a reality that is lived by thousands every day that have to hide their sexuality, gender identity, physical deviation, religion or political affiliation. It deals both with the loss of individuality and freedom, and with the harrowing realisation that the reality you have spent your life in for security and affirmation is slowly unravelling before your eyes. The Guardian’s film critic Peter Bradshaw describes it as “the eternal horror that can creep over you at any age – perhaps mostly middle age – that your own identity and everyone else’s is just a dream, a fake, an insidious illusion.” In the preface to Gollancz’s AF Masterworks edition of Finney’s novel, SF critic and editor Graham Sleight writes: “when, on the first page, [Miles Bennett] looks down from his office window at Main Street, it seems as if his gaze can encompass everything that goes on in [Santa Mira]. Certainly, as a doctor, he’s party to many of the stories that knit the place together. What’s most terrifying about the alien infestation is how it somehow corrupts this web of shared history.” These are themes that will always be topical, and that new generations can apply to their era and culture. So what is the movie really about? Well, naturally there is no “correct” answer, because the story is written and designed, probably not by accident, so that each reader or viewer can apply their own experiences and circumstances to it. And in that sense, the endless discussion about whether the movie was anti-communist or anti-McCarthy is moot. It is neither and both.

Author Jack Finney was a resident of the small town Will Valley on the coast of California, and the town serves as the backdrop to his book, disguised as “Santa Mira”. Wanger and Siegel initially intended to shoot the film on location, but realised that the 350,000 dollar budget would not allow for it, and scouted locations around Los Angeles that resembled Mill Valley. Several scenes were shot in Sierra Madre, including an iconic one where the pods arrive at the Santa Mira/Sierra Madre town square in trucks. When Miles arrives to Santa Mira in the beginning of the film, we see Becky pick him up at the Chatsworth train station — the building is still there today. And of course, the ever-present rocky landscape of Bronson Canyon and the Bronson Caves serve as the mining site over which the pair escape the mob in the end. With an original shooting schedule of 20 days, the work dragged to 23, of which only one day was spent in a studio. Dana Wynters tells Tom Weaver she really enjoyed working on the film. This was the first sizeable role for her in a movie, and she says everyone (almost everyone) on set were very supportive and “there” for her. She especially singles out cinematographer Ellsworth Fredericks. Wynter also says the whole crew, from Wanger and Siegel down to the gophers were tremendously professional; “And I think most of the actors were theatre people, so there was no waffling about and not knowing the lines. Also, there wasn’t a lot of discussion about motivation and all this kind of stuff. Performances were thought through [by the actors] and performed.”

All four lead actors had to have body casts made for their doubles. According to Don Siegel, he and the special effects team, led by Milt Rice and Don Post, had considerable trouble figuring out how to reveal the “bodies” as the popped out of the pods. The solution was soap bubbles. Bill Warren quotes Siegel as saying that the special effects budget was only 3,000 dollars, and credited his experience with special effects that allowed them to make good effects on the cheap. Dana Wynter recalls that the plaster casts got very hot and they could breathe only through straws stuck up their nostrils. She didn’t have any problems with the process though, except for the fact that the makeup people were “funny guys”, who joked around about going off for lunch while the plaster was setting. The giant seed pods are perhaps the most unintentionally funny element of the film, apart from a few voice-over lines. Not because there’s anything funny about the design, per se, but just the thought of these gigantic seed pods floating through space, coming down to haunt humanity. Usually in films like this, the threat is something invisible or some kind of monstrous goo or slime, which in itself is inherently “alien” and icky. But making evil incarnate take the form of rather sympathetic-looking seed pods does make you chuckle a bit. Of course, Jack Finney’s idea leans on the hypothesis of panspermia, as put forth by Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius in the early 20th century. The hypothesis states that life on Earth originates from outer space, carried in microscopic form to Earth through space dust or a meteorite. Finney super-sized the idea and gave the seed pods agency. Otherwise, though, the special effects of the film are actually quite creepy even today, partly thanks to the great reactions the actors give, but also because they are very well realised.

Speaking of the actors, as Wynters pointed out, almost all are seasoned stage veterans. Kevin McCarthy may not have been on the shortlist for the male lead, but he carries the film superbly. Big and broad-shouldered, with a theatrically trained, booming barytone, he has a charming easiness about him, and unlike so many leading men in fifties SF movies, he is instantly likeable. McCarthy is occasionally prone to a bit of theatrical over-acting, especially in emotional scenes, but it only adds to the psychological horror to see this chiseled piece of American hunk flail wildly in panicked terror. Every time I see the film, I am equally floored when Dana Wynters turns up for the first time, such an apparition! She has a dignified, cat-like sensuality about her, but at the same time, just like McCarthy, she seems rooted, somehow real and likeable. She shows off decent acting chops, even though she herself didn’t think she was very good in the “bland” role. And I am always happy to see King Donovan in a substantial movie role – this here is one of his career highlights, as Bennell’s pal Belicec. Donovan was a criminally underused character actor. Always on the mark, always right in tune with whatever role or film he made, always a pleasant, intelligent addition to the cast. Carolyn Jones, of course, is best known as Morticia Addams. She’s perfectly adequate as Mrs. Belicec, although her characterisation left no particular impression on me. The rest of the cast is made up of solid character and bit-part actors, whose strong and natural performances help sell the “unnaturalness” of the pod people they all eventually turn into.

This was one of the very few science fiction movies of the fifties that was squarely aimed at an adult audience. There had been films with similar themes, that also partly catered to adults, like It Came from Outer Space (1953, review) and Invaders from Mars (1953, review). The first, written by Ray Bradbury, had an intelligent and adult-oriented script, but was ultimately marketed as part of the juvenile sci-fi craze. The latter was sneakily rife with adult subtext, but with its kid hero and the crudely designed jumpsuited Martians tipped it definitively over into kiddie fare. The Thing from Another World (1951, review) had a somewhat similar theme, even if the body snatching element was removed from John Campbell’s original story. James Arness’ Frankensteinean monster also aimed the film more at the teens than the adults in the audience. Even the thoughtful and otherwise superb The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), with its clearly political ambitions, had a kid at the heart of the story in order to cater to the young SF fans. The one film that does feel like a precursor to Invasion of the Body Snatchers was William Cameron Menzies’ taut, paranoid noir thriller The Whip Hand (1951, review), in which communists have infiltrated a small fishing village, conducting strange experiments. Both Don Siegel and Walter Wanger vehemently protested the pulpy title Invasion of the Body Snatchers, thinking it misrepresented the movie as yet another juvenile monster film. But once again, Allied Artists overrode the whishes of producer and director. And perhaps to the detriment of the film.

At the time of its release, trade paper Variety gave Invasion of the Body Snatchers it a tentatively positive review: “This tense, offbeat piece of science-fiction is occasionally difficult to follow due to the strangeness of its scientific premise. Action nevertheless is increasingly exciting.” The dailies generally praised the film, with exceptions such as Dorothy R. Powers at The Spokesman-Review. “The plot, and most of the acting, would have been better off buried”, writes Powers, in a review that somehow seems less interested in engaging in film criticism than in telling the readers that science fiction is below the dignity of a movie critic. Leslie Dard at The Times (San Mateo) is less constipated: “Invasion of the Body Snatchers […] benefits from having been written […] by Jack Finney […] who drew on very real people and very real surroundings.” Dard continues: “Starting at a leisurely pace, the film’s action quickens at it moves toward the climax. Director Don Siegal [sic] has built up a high degree of suspense in the telling of the tale. McCarthy, though not a well-known actor, gives a good account of himself, despite some over-acting in the early portions of the film. Miss Wynter is both beautiful and capable of a good performance. In short: An off beat film […] combining tense action with a chilling plot.” In a tongue-in-cheek review at The San Fransisco Examiner, Hortense Morton writes: “During this one yesterday, coughers forgot to cough, the popcorn chompers didn’t chomp, and the cigaret smokers did it chain style. This is a six cigaret picture! A real nerve mauler.” And in the Elmira Star-Gazette, Jim Morse pens a positive capsule review, calling the film “a tense, off-beat piece of science fiction. Action builds to a strong climax. It’s good, provided you like that sort of thing.” Apparently the words “tense” and “off beat” must have been utilised heavily in the film’s press kit.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers was a juggernaut at the box office, raking in 2.5 million dollars in the US, and another half a million in the UK alone in 1956, thus making back its budget ten times over. Few, however, could have predicted its lasting popularity and legacy. To date, there has been three credited remakes, and dozens upon dozens of films have copied it central premise with success. Of course, its best known remake is Philip Kaufman’s eerie 1978 adaptation, set in San Fransisco. Then there’s Abel Ferrara’s 2003 remake Body Snatchers, a movie that divides audiences and critics, and The Invasion (2007) with Nicole Kidman and Daniel Craig, which was largely panned as a slick but soulless production.

The 1978 version is often considered one of the few remakes to actually outshine the original. The original, however, is still a staple on lists presenting the best SF movies of the fifties. ScreenRant puts it at #2, behind Gojira (1954, review), as does Den of Geek, behind The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review): “Unquestionably the greatest film to emerge from the 50s ‘reds under the bed’ era of communist paranoia, Invasion Of The Body Snatchers is one of the very best movies of the decade, irrespective of genre.” WatchMojo has it at #3, and Time magazine includes it on its list of the 10 best 50’s SF flicks: “Officially remade three times, this Don Siegel version is the simplest, sleekest and best.”

IMDb gives the movie a very positive 7.7/10 rating, based nearly 50,000 audience votes, and Rotten Tomatoes has a superb 9.1/10 critic rating (or 98% Fresh), based on nearly 50 critic reviews. It’s one of a small handful of 50’s SF movies to be included on Metacritic with a suberb 92/100 rating, based on 16 reviews.

Not all modern critics are beside themselves. An anonymous IGN review does call it “an excellent movie about paranoia”, but adds: “the performances are a little hokey, the dialogue is a little too on the nose”, and gives it a 7/10 rating. Jamie N. Christley at Slant magazine gives it 3/5 stars, citing the “flimsy, prosaic surface” and the script’s logic holes, but continues: “It’s precisely this inconsistency that makes the film’s metaphorical layer possible—a layer that’s weakened as each subsequent remake takes the bio stuff more and more literally […] The logical lapses […] generate a narrative fog that can accommodate […] sensations that are all the more vexing for their intangible qualities—a half-movie that takes up residence just beyond the periphery of our conscious awareness.” Apart from this, it’s pretty much straight aces all he way. Entertainment Weekly gives Invasion of the Body Snatchers an A+ review (“The power of the film is primal”), Empire gives it 5/5 stars (“Siegel’s isn’t a work of paranoia; it’s a sarcastic attack upon it”), as does Time Out (“the defining metaphorical work of the twentieth century”), TV Guide (“A superbly crafted film”), BBC (“one of the true masterpieces of the genre”) and the AV Club (“Siegel’s film continues to chill because it still feels unsettlingly familiar”).

Of my go-to online critics, surprisingly few have actually reviewed this movie, perhaps because so much has been said and written about it that there is little to add. But always worth a read, Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant writes: “A brilliant piece of sustained suspense, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is perhaps the talented Don Siegel’s best job of direction. Inspired by a screenplay that allows the Pod threat to grow organically (pardon) from within a setting of complete normalcy, Siegel emphasizes a creeping claustrophobia. Escape options fall away as the Pods close in, until our lovers must hide in a broom closet and pray they won’t be detected. Many Siegel efforts of the 50s are rushed, or take on a generic ‘docu’ look. Excepting a couple of police montages, Invasion is so well directed that one would not want to change a single shot.” Richard Scheib at Moria gives it 5/5 stars, writing: “Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a film that uses the fear of night probably more so than any other horror film ever made – night and sleep are the realms of fear, day is the realm of reason. What is interesting is that the film sides with irrationality and night, rather than day and reason. Much of the latter half of the film builds with the relentless sense of things spinning out of control that a nightmare does. The climactic scenes with Kevin McCarthy running on a highway, his cries for help being ignored by the passing cars and his leaping onto the back of a truck only to find it filled with pods makes much more sense in terms of dream logic than rational storytelling.” Even Andrew “Zero Stars” Wickliffe at The Stop Button is (mostly) sold, with a 3/4 star review: “Even with the three times clunky finish—even without the framing device, it’s impossible to imagine what the film would play like without the added narration and since that narration screws up the third act, there’s not a lot going right outside the spectacular technical filmmaking–Invasion of the Body Snatchers is exquisite. It’s a step higher than almost great (so pretty great?). It just should and could be better. And—rather frustratingly—would have been better, had the studio just kept their hands off it.”

There is, as mentioned, little to add to the praise that this film has received over the years. Given its small budget, it’s amazing how good the film looks, from its cinematography and lighting to the few, but impressive special effects. It is one of the very few horror movies on the flipside of the sixties that is actually still scary today, thanks to the absence of rubbery monsters and to the relentless psychological terror that keeps building over the course of the picture. If you want to pick on something, then I would agree with Andrew Wickliffe that the third act of the film, disregarding the very last three scenes, feels a bit drawn out, at least on subsequent viewings. On the whole, it is not a film that holds up particularly well to repeated viewings in the same way as some other classics. Once you know what’s going on and how the twists and turns of the script will shape up, it loses some of its potency.

Beside directing a couple of Twilight Zone episodes, and appearing in a cameo as a taxi driver in the 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Don Siegel didn’t dabble further in science fiction. A Cambridge educated American, he studied art and found work at Warner Bros.’ film library in the late thirties. He honed his editorial skills for seven years working with montages, including the opening montage of Casablanca (1942), and eventually rose to the head of the montage department. In 1945 he directed two short films, Star in the Night and Hitler Lives, that won the Academy Award and launched his directorial career. As a director, Siegel took to the noir style, creating himself a reputation as a maker of tight, intelligent, psychological thrillers and crime dramas, but he worked in a number of different genres. Almost all his films were low-budget fare, but Siegel’s eye for visuals, lighting, and composition, and his technically superb cinematography allowed them to transcend their measly budgets. He was noticed, at least by producers, in 1954, for Private Hell 36 and the above mentioned Riot in Cell Block 11, which led to him getting the chance to direct Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In 1960 he directed Flaming Star, generally considered Elvis Presley’s best film, and in 1968 the action comedy Coogan’s Bluff, which led to a life-long friendship with its star Clint Eastwood. Their collaboration continued with Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970) and The Beguiled (1971) and peaked with the 1971 surprise box office and critical megahit Dirty Harry (1971). The fourth-highest grossing film of 1971, it influenced the entire genre of the police thriller. After working with John Wayne, Michael Caine and Charles Bronson, Siegel caught up with Eastwood again for a fifth and last film, Escape from Alcatraz (1979), another critical and box office success. His last film, Jinxed! (1982) was a straight-up comedy starring Bette Midler. Clint Eastwood has said that he owes what he knows about direction to Don Siegel. Another director whom Siegel was central to was Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah started as a gopher and worked with other menial tasks in at Allied Artists, before Siegel hired him as dialogue director in five of his pictures, including Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Peckinpah appears in a small cameo as a utilities man in the Belicecs’ basement.

Lead actor Kevin McCarthy was actually distantly related to senator Joseph McCarthy. Even though he appeared in over 100 films and as many TV shows during his long career, he always considered himself primarily a stage actor. Although born in Seattle, he spent much of his life in New York, where he regularly appeared on Broadway. He appeared in the original broadway run of Death of a Salesman, and reprised his role in an Oscar-nominated and Golden Globe-winning turn in the 1951 movie adaptation. He was not the first, second, or even fifth choice to play the lead in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and can probably thank Don Siegel for the opportunity, as it was Siegel who had given him his first starring screen role in the drama programmer An Annapolis Story in 1955. Never one of Hollywood’s brightest stars, McCarthy was nevertheless a respected character actor who worked steadily in film, TV and on the stage in a career that spanned eight decades. For some time, McCarthy was annoyed that people always wanted to talk to him about Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but in later years he discovered, as so many of the actors in horror and SF movies, that it was because of his genre work that he was remembered at all, and embraced his role as a sort of ambassador for the movie. His involvement in the film also brought him a number of cameos and supporting roles in SF productions, first as guest appearances in TV shows like The Twilight Zone, Wild Wild West and The Invaders, then in TV movies and finally in feature film, much thanks to horror film aficionado Joe Dante, who cast him in a featured role in Piranha (1978), the lead in Dante’s segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983) and lastly in another large supporting part in Innerspace (1987), a movie also featuring SF alumni like William Schallert and Kenneth Tobey in cameos. He played an uptight villain in a suit in the Weird Al Yankovic picture UHF (1989), had cameos in Eve of Destruction (1991) and Trail of the Screaming Forehead (2007) and must have had a blast playing The Grand Inquisitor in the indie comedy The Ghastly Love of Johnny X (2012) at 93 years old. He sadly passed away in 2011, before the film was released. The movie was notable for being the lowest grossing film of 2012 in the US, taking in 117 dollars during its one-week theatrical run, and as the last film ever to be shot on Kodak Plus-X film stock. It has since become a cult favourite. And of course, he famously had a cameo reprising his crazed highway ravings in the 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Dana Wynter praises Kevin McCarthy, saying “You feel there’s not a shadow on Kevin. He doesn’t speak badly of people, he’s full of praise, he’s full of enthusiasm, you feel that he’s decent through and through and through and through. Apart from being so charming. And he doesn’t have that actor thing — I really don’t care for actors very much!”

Lead actress Dana Wynter was born Dagmar Winter in Berlin, but grew up in England and South Rhodesia, where she initially planned on following in her father’s footsteps and become a doctor. However, in her late teens she decided to turn to acting instead, and appeared on stage and in small roles in British films in the early fifties. In 1953 she was spotted by an American agent, who took her to Hollywood, where she struggled for a while, but got a lucky break when Eva Gabor fell ill and had to withdraw from the lead in an episode of the The Robert Montgomery Show. Wynter was pushed in as a last-minute replacement, and did so well that it opened the door for her to go on and appear in a number of other shows. Invasion of the Body Snatchers was her first film role in Hollywood, apart from a small walk-on part. Following the film’s success, she got a 7-year contract with Fox, which was a mixed blessing. Interviewed in Tom Weaver’s book I Was a Monster Movie Maker, she says she was unhappy about many of the movies she was in, and the studio didn’t allow their stock actors to do anything outside the studio in the gaps between the films they were assigned, which could often be pretty long stretches. Finally, when she was invited to play the lead in the 1957 episode “Winter Dreams” on one of the most popular and prestigious TV shows, Playhouse 90, she took the battle to the studio brass, who, after reading the script, decided to change their policy and rent her out to the TV station. Back in the day, these kind of anthology TV shows would often do what was more or less TV movies that were broadcast live. Playhouse 90, for example, made episodes that were 90 minutes long. In essence, these were filmed plays, but on a set rather than on a stage. At best, Playhouse 90 had 40 million people per episode. Wynter tells Weaver that the three Playhouse 90 episodes she starred in were her favourite in all the work she did in Hollywood, as they were demanding parts that allowed her to learn and stretch herself, whereas the movies she did for Fox were mainly B programmers. She tells Weaver that during one of her Playhouse 90 episodes, one of the four cameramen was electrocuted in the middle of the broadcast and “through the corner of her eye” Wynter saw how he just fell from his camera on the floor. Another cameraman who had just happened to walk in from another show to watch director John Frankenheimer work jumped onto the camera and told the booth he’d try and keep up although having no idea what the show was even about, if Frankenheimer would guide him through it: “Now that sort of thing never happened in film — I mean, it was all sort of dull in comparison”.

In 1956 Wynter married celebrity divorce lawyer Greg Bautzer, which gave her a financial security that would have allowed her to leave Fox, but the studio refused to break her seven-year contract. Finally free from in in 1961, she continued to work in TV, appearing as a guest star in numerous shows, and did the occasional movie role, perhaps most notably in John Huston’s The List of Adrian Messenger (1963) and the classic Airport (1970). Relocating to Ireland, she created a second career for herself as a journalist in the eighties after divorcing her divorce lawyer and leaving acting behind. She passed away in 2011, the same year as co-star Kevin McCarthy.

King Donovan is one of my favourite actors of the fifties SF movies, and unfortunately criminally underused. One of his largest roles was the second lead as Richard Carlson’s investigator partner in Ivan Tors’ surprisingly good The Magnetic Monster (1953, review). He had a walk-on part in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review) and another blink-or-you’ll-miss-it role in Tors’ Riders to the Stars (1954, review), and a third one in the SF comedy Nothing Lasts Forever (1984, review), which remained his last film before his death from cancer in 1987. A man of both comedic and serious acting talent, Donovan often played wholesome white picket fence types, clerks, scientists, middle-class fathers and neighbours. The son of two vaudeville performers, he cut his teeth in the Butler Davenport Free Theatre in New York in his teens, a socialist off-Broadway troupe offering audiences free tickets. Like McCarthy and Wynter, he perhaps felt more at home on stage and in TV than on the film set. However, musical comedy fans remember him for his portrayal of the saturnine assistant director in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), or as Solly in The Defiant Ones (1958), starring Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier. His many TV appearances include the recurring role of Harvey Helm on the Bob Cummings sitcom Love That Bob! and Herb Thornton on the 1965-66 family comedy Please Don’t Eat the Daisies. Long married to comedienne Imogene Coca, King Donovan frequently co-starred with his wife in such stage productions as The Girls of 509 and his last theatrical effort, 1982’s Nothing Lasts Forever. Donovan dabbled in directing, and is perhaps best remembered for directing the 1963 production Promises, Promises, which is historically significant for being the first American mainstream movie to feature its female star fully nude. The star in question was Jayne Mansfield.

Carolyn Jones is the most famous of the four lead actors, and the one that somehow leaves the least impression on me. Jones is perfect as King Donovan’s nervous wife, but for some reason or the other just doesn’t stand out — her role is rather inconsequential. After training for the stage, Jones secured a contract with Paramount in 1952, and appeared in small roles in film and larger ones in TV. Compared to Wynter, she was a veteran, and Wynter says she was the only one on the set of Invasion of the Body Snatchers she didn’t get along with. She says she learned a lot from Jones, among other things how not to behave toward fresh, young actresses. Jones was often cast in somewhat kooky, nervous or edgy roles, and was instantly classic in her short, black hair in the 1957 film The Bachelor (she’s the one uttering the classic line “Just say you love me. You don’t have to mean it!”. Her eight minutes on screen earned her an Academy Award nod, and a Golden Globe Award for “new star of the year”. Her final breakthrough came in 1964 when she was cast as Morticia Addams on the TV show The Addams Family. However, the show was cancelled after two years, partly because of stiff competition from The Munsters and Bewitched, and her typecasting now led to troubles finding roles. She returned to the stage, but made a comecback in Hollywood in the mid-seventies, and had good success as a guest star on numerous TV shows, including Wonder Woman (1976-1977) where she played the titular character’s mother Queen Hyppolita. In 1982 she secured a recurring role on the soap opera Capitol, even though she was already diagnosed with terminal cancer. She passed away in 1983.

Another central role of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is that of Santa Mira’s psychiatrist, played to perfection by noted character actor Larry Gates. Although he’d been in the game for a while, mostly on stage and in television, this was his first stand-out role on film. He also had memorable turns in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and In the Heat of the Night (1967). He made a splash in his Broadway debut in the comedy Bell Book and Candle in 1956, and was nominated for a Tony Award in 1964 for his role in the Broadway show A Case of Libel. Gates worked steadily on film over the years, although like many theatrical actors, preferred TV. He received a Primetime Emmy award for his work as H.B. Lewis in the TV series Lighthouse in 1985, a role he played between 1982 and 1993. Miles Bennell’s nurse is played by Jean Willes, a talented actress with a steady and successful career in film and TV, that was often hidden away in bit-parts. Willes also appeared as a villain in the quasi-sci-fi Jungle Jim in the Forbidden Land (1954, review), in The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957) as well as the TV shows The Adventures of Superman and The Twilight Zone.

And in the role as the psychiatrist on the framing sequence, we see another of my favourites, Whit Bissell. Bissell is known to friends fifties horror and SF films as the eternal straight-laced, often mild-mannered and competent scientist, physician, government official or military man. He is best known to a wider audience for one of his rare villainous roles, that of the evil scientists who turns future Charles Ingalls, Michael Landon, into a werewolf in I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review). But his SF credit sheet is a mile long, and memorable performances include Dr. Thompson in Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), a small but important role as one of the time traveller’s sceptical friends in George Pal’s The Time Machine (1960) and his portrayal of the evil Governor Santini in Soylent Green (1973). He also appeared in a small role in Lost Continent (1951, review), played a military scientist in Target Earth (1954, review), reprised his villain in I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957, review), appeared in Jack Arnold’s Monster on the Campus (1958), played Dr. Holmes in Irvin Allen’s TV movie City Beneath the Sea and reprised his role in a TV remake of The Time Machine (1978). Bissell was also a familiar face in science fiction TV from the fifties onward, appearing in many anthology shows, such as Out There and Science Fiction Theatre. His most prominent SF role was that of Lt. Gen. Heywood Kirk, one of the main characters of the TV series The Time Tunnel (1966-1967). Other memorable SF moments on TV for Bissell are the 1959 Christmas episode of Men into Space, the injured navy captain at the heart of the One Step Beyond episode Brainwave (1959), as small role as commanding officer in The Outer Limits episode Nightmare (1963), guest starring a young Martin Sheen, Mr. Lurry, the station Manager of the space station involved in the legendary Star Trek episode The Trouble with Tribbles (1967), and as one of the scientists studying the captured Hulk in The Incredible Hulk episode Prometheus: Part II (1980).

Born Whitnell Nutting Bissell in 1909 in New York, he was the son of a surgeon and took to acting during his university studies in North Carolina , where he majored in drama and English, training with the Carolina Playmakers. He then moved to New York, where he had a short stint at Broadway, including the smash hit Winged Victory while he was drafted to the US Air Force. He made his screen debut in 1943. While never a marquee name, his reliability and versatility offered him a constant flow of work in Hollywood over four decades. He appeared in over 200 films and scores of TV shows. Bissell served for many years on the board of directors of the Screen Actors Guild, and represented the actors’ branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences board of governors. The only reward he ever received for his long and distinguished career was a life career award from the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films. He passed away in 1996.

A memorable appearance is also put in by Virginia Christine, who plays Becky’s cousin whose uncle Ira isn’t Uncle Ira in the beginning of the movie. Christine was another character actress who had a long and successful career in films and TV shows. However, while some win Oscars and Golden Globes, Christine was honoured by her small hometown of Stanton, Iowa with a water tower in the shape of a coffee pot. This was thanks to her most memorable role, that of Swedish Mrs. Olson in a string of widely broadcast commercials for Folger’s coffee. Mrs. Olson appeared in these with hapless young housewives who had no clue as to how to make their husbands a perfect pot of coffee, but Mrs. Olson was always able to set them straight, with Folgers’ “mountain grown coffee, the richest kind there is”. Christine appeared in over 100 commercials for Folgers from 1965 onwards, and her character became so well-known that it was regularly parodied by entertainers and comedians like Carol Burns, Bob Hope and Jackie Gleason. Trained for the stage, she made her film debut in 1943, and during her career appeared in such prestige films as High Noon (1952), Judgement at Nurenberg (1961) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), mostly in minor roles. In the forties Christine had the chance to play leading lady in a number of B movies — horror fans may recognise her as Lon Chaney Jr.’s immortal love interest in The Mummy’s Curse (1944). In the fifties she transitioned into TV, although she did appear in the occasional movie. However, the TV work kept her out of the sort of B-work she had trudged through in the forties and early fifties. She more or less retired in the early seventies, even if she did the occasional TV appearance up until 1982, and still did coffee commercials well into the eighties. She passed away in 1996.

Janne Wass

Invasion of the Body Snatchers. 1956, USA. Directed by Don Siegel. Written by Daniel Mainwaring, Richard Collins. Based on the novel “The Body Snatchers” by Jack Finney. Starring: Kevin McCarthy, Dana Wynter, King Donovan, Carolyn Jones, Larry Gates, Virginia Christine, Jean Willes, Whit Bissell, Ralph Dumke, Tom Fadden, Bobby Clark, Eileen Stevens, Guy Way, Beatrice Maude, Sam Peckinpah. Music: Carmen Dragon. Cinematography: Ellsworth Frederick. Editing: Robert Elsen. Production design: Ted Haworth. Makeup artist: Emile LaVigne. Sound: Ralph Butler. Special effects: Milt Rice, Don Post. Produced by Walter Wagner & Walter Mirisch for Allied Artists.

Leave a comment