Famous for its villains with ping pong ball eyes, this 1953 low-budget entry sees Peter Graves abducted by aliens planning to invade the Earth. Sadly, the stale script isn’t nearly as fun as the design of the antagonists would suggest. 2/10

Killers from Space. 1954, USA. Directed by W. Lee Wilder. Written by Myles Wilder & William Raymond. Starring: Peter Graves, James Seay, Steve Pendleton, Frank Gerstle, John Frederick, Barbara Bestar, Shepard Menken. Produced by W. Lee Wilder. IMDb: 3.5/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

First, we have to address the eyes – the wonderfully wacky ping pong ball eyes. This 1954 film was supposed to be serious – and the aliens were supposed to be frightening. And then they stuck ping pong balls on their eyes. It’s wonderful! Well, in fact, they are not ping pong balls at all. Director Willie Wilder had suggested ping pong balls, but makeup artist Harry Thomas thought that wouldn’t look realistic, so he went to an optical shop to ask for glass eyes that he could cut in half. But they cost 900 dollars apiece, which was probably more than Thomas’ entire makeup budget. John Johnson’s book Cheap Tricks and Class Acts quotes an article in Filmfax, where Thomas is interviewed. Thomas describes how after being turned down at the opticians’, he stayed up all night wrestling with the problem of the aliens’ eyes, and how to make them realistic, so he wouldn’t have to settle for Wilder’s idea with the ping pong balls: ”I was almost completely discouraged when I opened up the refrigerator to get something to drink, and there was my answer: a white plastic egg tray.” So there you have it. In your face, haters, those are not ping pong balls, they are very realistic egg tray bottoms.

The film itself follows the exploits of nuclear scientist Dr. Douglas Martin (Peter Graves), who is accompanied in his plane by the same kind of narrated military stock footage that director Willie Wilder used in his 1953 film Phantom from Space (review). This time, however, it isn’t an alien UFO that crashes, but Martin’s plane, as he and his pilot are out and about monitoring a nuclear test near the Soledad Flats. The stock footage rescue team finds the pilot dead, but no trace of Martin. However, shortly after, a dishevelled Martin stumbles into the test facility, with no recollection of anything after the crash — or about how he got a strange surgical scar on his chest. His superiors and the FBI think it best that, until the mystery is solved and Martin can be deemed sound of mind, he take a vacation. However, despite the pleas from his wife (Barbara Bestar), Martin can’t keep away from his job, and one day walks in, steals some top secret data, drives out to the Soledad flats and places a note under a rock. Unfortunately he is caught red-handed by FBI investigator Briggs (Steve Pendleton), who seems to be constantly strolling around the nuclear test site. When apprehended and under the influence of “truth serum”, Martin tells us “the whole story”.

33 minutes into the 70-minute film we meet the egg-tray-eyed aliens, dressed in leotards resembling the Phantom. This 20-minute sequence is told in flashback, as Martin awakes on a slab in a cave filled with blinking machines, seeing the alien surgeons holding up his beating heart in front of him, then replacing it in his chest. This is, naturally, where his care came from. Their leader Deneb (John Frederick) informs him that he died in the crash and was brought back to life so that he could aid them in getting information on the last nuclear test. Turns out the aliens are using the energy released in the nuclear tests to create gigantic insects and lizards, all of which Martin meets in a poorly staged 10-minute rear projection sequence as he tries to escape. As Deneb informs him, the aliens’ home planet is dying and they intend to invade Earth — but not before unleashing the giant critter plague upon the planet, which will devour all living things, leaving the house ready for its new inhabitants. When Martin refuses to save his own life by helping the aliens, Deneb calls on the great Tala (John Frederick again), to appear on one of his screens to hypnotise Martin and force him to do the aliens’ bidding. End of flashback.

The third act of the movie consists of Martin arguing with his doctor (Shepard Menken) and superiors (James Seay, Frank Gerstle) about his state of mind, and about the necessity to shut down power in the entire state (you see, the aliens are tapping into the power grid, and cutting off power will make their base explode). Meeting only with disbelief, Martin escapes the base hospital in pyjamas and a hospital gown, determined to shut down the power plant on his own.

And what about those eyes, you may ask. Well, as Deneb tells Martin, the aliens’ sun is fading, and the aliens have developed egg tray eyes in order to cope with the darkness.

In truth, Killers from Space has all the makings of a good B movie. The story, concocted by director William Lee Wilder’s son, Myles Wilder, is not a bad one. The attempt to meld a spy thriller with an alien abduction scheme has worked up to this day, with X-Files as the penultimate example. Wilder takes his cues from alien mind control stories such as the one found in Invaders from Mars (1953, review) and combines it with the always popular amnesia trope (done to perfection in Richard Condon’s 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate and carried on in Robert Ludlum’s 1980 book The Bourne Identity), and is careful not to reveal the aliens until halfway through the film. Granted – the script is clumsy and illogical and the dialogue, especially the one involving the aliens, is disastrous, but Myles Wilder and his tag-team buddy William Raynor weren’t totally useless writers, as they proved with their successful TV work later on. With even a semi-decent budget and a good director, say like Jack Arnold or William Cameron Menzies, this could have been a minor science fiction classic in the vein of It Came from Outer Space (1953, review).

But, alas, they are stuck with a shoestring budget and Willie Wilder. I have written in length about Wilder Sr. and Jr. in my review of their previous film Phantom from Space, so head over there for some more insight. But briefly: William Wilder was the older brother of the accomplished Austrian writer-director Billy Wilder. In 1945 Billy’s estranged brother Willie took some of the money he had made as a successful handbag manufacturer in New York and set himself up as an independent film producer in Los Angeles. Phantom from Space was his third feature film as a director, and the first of his early fifties sci-fi trilogy, the others being Killers from Space and The Snow Creature (1954, review). These three have become his most lasting legacy, and are often considered among the worst of all the inane science fiction cheapos made in the decade. He directed eight more films in the fifties and sixties, including the sci-fi tinged The Man Without a Body (1957, review) and a last science fiction-ish movie called The Omegans (1968)

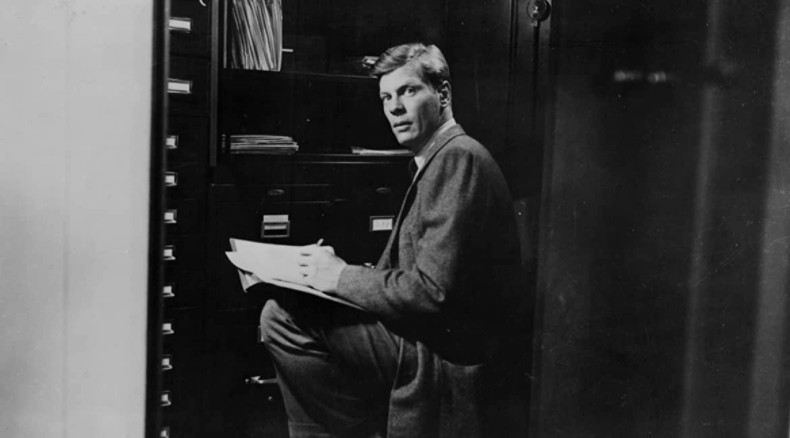

Peter Graves carries Killers from Space on his shoulders. Not the most versatile of actors, he is sometimes prone to overacting in the movie, especially in scenes where he is reacting to things that are not on screen, or fleeing from rear-projected gigantic critters. But he never lets on that he is working in a basement-studio production or that the proceedings are sometimes downright silly. Thus he lends an air of dignity and realism to the movie, and never seems to be phoning in his performance.

There isn’t much in the way of special effects in the film – apart from the strange equipment in the alien lab and the rear-projected critters. So little, in fact, that the film doesn’t even have a credited special effects crew. The stacks of machines appearing in the aliens’ cave were probably salvaged from some other film, and blinking neon tubes and arc generators were not hard to come by in Hollywood in the fifties. At least in Phantom from Space, there were some rather impressive invisibility effects, here all effects shots are stock photo explosions, stock photo animals or bits and pieces cobbled together from other films, mainly a few miniature shots of rockets, space stations and futuristic cities – I can distinctly make out the Martian city from the 1951 film Flight to Mars (review), one of the most re-used miniature shots in SF history.

The rear-projected shots of the spiders and lizards and bugs behind Peter Graves are clumsily done, and Graves seems to have been given very little direction about what he should be doing. The whole sequence with Dr. Martin running around in the caves is painful to watch, as it is seems nobody on set had any sense of what was supposed to be going on, other than having Graves running back and forth in Bronson Canyon. The change in film stock quality when mixing actual film footage and stock footage is blatant throughout the movie, even from looking at the grainy version available for home viewing. When a nuclear explosion is supposed to go off in the desert, one can clearly see that it is a US atom bomb test. At sea. With ships in the sea.

The film was clearly shot in a rush, since Wilder and cinematographer William H. Clothier seem to settle for as few set-ups of each scene as possible, and some scenes are simply done with one single, static camera shot. To the film’s credit, we do see a little more than bare offices, as Wilder does try to take us out in the open and change locations as much as possible. Still, there’s no escaping the dreary scenes where actors stand lined up against a white wall with a chair and a desk to make it look like an office. For one scene we get little more than two people talking to each other from separate corners of the screen, while the camera centres in of a portrait of president Eisenhower. For five minutes or so. For the final climactic scene, Wilder had the privilege to film at an actual power plant, and the surroundings are pretty impressive. Unfortunately, he doesn’t quite manage to use the camera with any sort of imagination, to take advantage of the location, instead we get people running through one static shot into the next one.

All characters in the film are flat and one-dimensional, and there is no character development to speak of. The film is only 70 minutes long, but the lack lack of any sort of subplot or dialogue outside of the what is necessary to move the plot along force the filmmakers to pad out the film with stock footage and endless silent stretches of people running, driving and walking. The plot could easily have been condensed into a 30 minute TV episode.

Thematically, the film follows the issues of the time without much deviation. This was the height of McCarthyism, when Americans were looking for Russian spies under every bed. However, for diplomatic reasons censors didn’t want creators of fiction to actually say they were looking for Russian spies under every bed, hence the many creative metaphors we see in films from this era, where people are talking about ”foreign powers” or ”the enemies of freedom”. In Killers from Space, it isn’t hard to see the the mind-controlling aliens as a metaphor for the communists, secretly building up their army for an invasion, but the script is so thin that not even this simplest of SF tropes gets any real footing, as the screenwriters never stop long enough to ponder the issue. Instead the aliens’ motives are on a first-grader’s level: our planet is dying, we will kill everyone and take over the Earth.

The other Big Issue of sci-fi in the fifties was nuclear power and the atom bomb. More often than not, the fear was that the Soviets might develop long-range missiles armed with nuclear warheads, capable of launching them across the Pacific of the Atlantic ocean. Furthermore, advances in rocketry, such as the development of the V2 rocket and other technology sparked the idea that the first country to conquer space would be able to place nuclear weapon platforms either on the moon or in orbit around the Earth. Such worries were the driving force behind films like Destination Moon (1950, review) and Project Moonbase (1953, review). In these films, the fear of nuclear weapons was strictly that atom bombs were incredibly powerful bombs that could lay waste to whole cities. Very few at the time – even among scientists – understood the long-term danger of radiation and radioactive fallout. There were films that dealt with the dangers of atomic power, such as Five (1951, review) and The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), but not even their bleak visions could do justice to the real horrors of a nuclear explosion. Unsurprisingly, Killers from Space doesn’t get it either, with our heroes peacefully strolling around the test site.

All in all, Killers from Space is a film where the hot topics of the time informs the storytelling more than the other way around. Whether or not Wilder & Wilder had any intent to comment on either of the topics listed above is unclear, but whatever the case, these discussions are lost in the thinness of the script. As such, the film has more in common with the juvenile entertainment of the Flash Gordons (1936, review) of the thirties and forties than with afore-mentioned socially charged movies.

Among the many mundane camera setups are small moments of quality. Phantom from Space and Killers from Space were among the first films as director of photography for William H. Clothier, a Hollywood legend who worked on dozens on westerns with John Wayne and John Ford, including The Alamo (1960), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Cheyenne Autumn (1964) and Big Jake (1971). He was nominated for two Oscars. In Killers from Space especially two shots stand out; both POV shots. The first one is the air base doctor checking Dr. Martin’s eyes, which is a very eerie close-up of Shepard Menken’s face, and the other is the shot of Martin waking up after his crash, seeing three strange aliens doing something with scare, smoking instruments, then the shot switches so we see Martin’s own heart beating on top of his chest.

The editing is ghastly. People appear from out of nowhere and there is shot after shot of people running from one static shot through another. This is most tiresome in the underground sequences and in the sequences at the power plant. The pacing is constantly off and there are too many unedited stretches of single takes.

Contemporary critics, as far as they noted the Killers from Space, where not impressed. Boxoffice wrote: No success whatsoever met this obvious attempt to parley some stock footage, a collection of pseudo-scientific props and touches of trick photography into suspenseful space-opera which might capitalize on the current popularity of pictures of its category.” Variety called it “a routine affair where more adroit handling might have upped into a true chiller”. Wood Soanes at the Oakland Tribune noted in his review that he couldn’t inform the readers about how the film ended, “since the picture ran 71 minutes and 50 was all I could stand”.

Today, the film has a 3.5/10 rating on IMDb and not enough entries for a Rotten Tomatoes consensus. AllMovie gives Killers from Space 1/5 stars, and Craig Butler writes: “Unfortunately, somehow director W. Lee Wilder manages to take all the fun out of what should be a crazy misfire of a movie, making a film that is so tedious and dull that all the fun drains out of it within the first 15 minutes. Clearly, Wilder was attempting to treat this material with seriousness, which is not a crime. But his work here is so lacking in any skill, so lacking in any sense of pacing or structure or ability to build suspense, that he makes Killers a chore to sit through.” TV Guide writes: “Cheap and idiotic, this film employs motifs that might have suggested allusions to 1950s politics had more thought been put into the screenplay. As it is, the picture contains bad stock footage, bad costuming for the aliens, and bad acting from everyone involved.”

Film historian and critic Bill Warren wrote: “Killers from Space suffers from slow pace, mediocre acting and cheap production values, all of which detract from the interesting basic premise”. And in The Sci-Fi Movie Guide, Chris Barsanti notes that while the film does contain some atmospheric photography, “some incredibly shoddy f/x […], along with a lethargic pace, put this one deep in the trash barrel”. Clive Davies in Spinegrinder calls it “pretty but, but worthwhile if only for the aliens”. Richard Scheib at Moria writes: “In all regards, Killers from Space is routine. W. Lee Wilder generates almost nothing in the way of suspense during the chase sequences. The film loses credibility altogether once it introduces the ridiculous looking aliens in hooded boiler suits and with ping-pong ball eyes and shaggy eyebrows, looking for all the world like they are wearing mass-produced joke store masks. Wilder valiantly tries to obtain some effect by sinisterly underlighting them but the ludicrousness of their look sinks the film.”

However, both Killers from Space and W. Lee Wilder have their genuine fans, even if they are few and far between. One of the most heartfelt praises of Wilder I’ve read comes from Jim Knipfel at Den of Geek, who writes that ”W. Lee was a much more interesting and adventurous filmmaker than his brother” and that ”he did have some fine, sharp little scripts (often written by his son Myles) and an undeniable cinematic flair. Somehow, perhaps pure chutzpah was behind it, or a touch of dark alchemy, or simple madness, all those sub-par onscreen elements came together into some mighty spellbinding wholes”.

In Jim Knipfel’s defence, I haven’t seen all of Wilder’s films, but I do feel that the praise he heaps on Phantom from Space and Killers from Space is a tad inflated. While it is true that both films have the feeling of being made by a mad scientist, the simple truth is that the quality just isn’t there. With both movies there is the nagging feeling that there’s a good premise in the original story – but that’s thanks to Myles and not Willie. Myles later proves himself as a quality player in Hollywood, Willie never did.

I would agree that W. Lee Wilder wasn’t the same sort of clumsy amateur that Ed Wood was, but there were a bunch of decent directors and producers in Hollywood in the forties, fifties and sixties that churned out pictures on shoestring budgets with far better results, even if they weren’t all as wacky as Wilder. Sam Newfield and William Beaudine, for example, and let’s not forget the king of the cheapo movies, Roger Corman, who worked on even smaller budgets than Wilder, often with better results. What Wilder did have in common with Wood was that his reach exceeded his grasp, which is why we remember him today. Trying to make Big Movies with Big Ideas with neither the talent nor the budgets to do so, his films are spectacularly memorable failures, rather than decent, but forgettable B movie fair. Another reason we remember Killers from Space is that the movie fell into the public domain quite early, since nobody renewed its copyright license, and because it was riffed on by the Film Crew, a MST3K-type group some years ago. And because of the egg trays.

And I disagree with Richard Scheib who writes that it is the wacky-looking aliens that sink the movie. The aliens in Invaders from Mars were equally kooky, but that film still works, and what doesn’t work isn’t the fault of their baggy velour suits. No, Killers from Space is killed off because nothing else in the film comes even close to the outrageousness of the aliens. While the ludicrous aliens do destroy any credibility the film tries to build up as a serious chiller, the real problem is that the rest of the movie is at the same time so incredibly dull and so slapdash.

Billy Wilder (born Samuel) is of course regarded as one of the top directors in Hollywood during the forties and fifties, while Willie (born Wilhelm) is regarded as the talent-deprived embarrassment of the family. Willie helped out the penniless Billy when he arrived in Hollywood from Nazi Germany, but for some reason the two brothers didn’t seem to get along – they never collaborated, and rarely spoke of each other in public. One of the few times Billy mentioned Willie, he jokingly called him ”a dull son of a bitch”. According to Willie’s granddaughter Kim Wilder, who writes about her granddad at Kid in the Front Row Film Blog, there wasn’t any special reason for the animosity between the two, other than the fact that Billy Wilder was a difficult and self-absorbed man, who was more interested in his own art and his ”rich Hollywood friends” than his family. However, there is a connection between the two Wilders in Killers from Space, and that is lead actor Peter Graves.

Peter Graves was an up-and-coming actor who got something of a breakthrough in Billy Wilder’s lauded WWII drama Stalag 17, released the same year as Killers from Space. I have covered Graves earlier on the blog, in my review of the terrible 1952 movie Red Planet Mars. Graves was never the most versatile of actors, but did a good enough job within his own parameters, that with the help his athletic build, his ruggedly handsome features and his stern blue eyes and blonde hair, he was able to carve out a rather successful Hollywood career, but as the blog X-Entertainment puts it: more in a ”’you’re supposed to know what he’s done’ way than an actual ‘you know what he’s done’ way”.

During the fifties Graves trudged on in supporting roles in A-films like The Night of the Hunter (1955) and The Naked Street (1955), and played leads in a number of B movies, including a few sci-fis. But he found his real success in TV, starting with the lead in the western drama Fury (1955-1960), following up with the Australian western series Whiplash (1960-1961) and the British Court Marshal (1965-1966). To baby boomers, however, his real claim to fame is as the grey-haired leader of a team of American agents infiltrating foreign baddies all over the world. As Jim Phelps in the groundbreaking spy series Mission: Impossible (1967-1973) Peter Graves became an A-list celebrity worldwide, and the role landed him a Golden Globe in 1971. He reprised his role in the remake (1988-1990), but turned down the role in the Tom Cruise movie in 1996, because the script revealed Jim Phelps as a traitor.

A younger audience may know Graves from his legendary turn as Captain Clarence Oveur in the Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker comedy Airplane! (1980), where he asks a young boy if he’s ”ever seen a grown man naked”, and in the sequel from 1982. In an interview Graves confesses that at first he threw the script for Airplane! across the room, as he thought it was rubbish, but upon second reading he realised how the role made fun of his history of steely, stone-faced hero types, and he slowly started to chuckle. Graves is treasured in sci-fi circles because of his appearance in a number of bad B movies, like It Conquered the World (1956, review) and Beginning of the End (1957, review). He had the leading role in The Clonus Horror (1979) and had a cameo as himself in Men in Black II (2002). He also appeared in a few TV films, including The Eye Creatures (1965) where he did an uncredited voice-over, and the interactive movie/computer game Darkstar: The Interactive Movie (2010), where he acted as narrator. Graves’ real name was Peter Duesler Aurness. Sci-fi fans may know his brother James Arness as the Thing in The Thing from Another World (1951, review). However, he is of course best known for his long-lasting fame as one of the main cast in the legendary TV series Mission: Impossible. Graves was the brother of actor James Arness, of Gunsmoke fame – for SF fans best known for playing the alien in The Thing from Another World (1951, review).

Regarding the cast, there are few worthy of much mention apart from Peter Graves. However, credit must be given to John Frederick, who plays the leader of the aliens with a completely straight face, not that this makes the performance any better. This was probably one of his largest roles, as his 70 film and TV roles are mostly of the ”2nd officer of Wehrmacht” or ”Police officer in car” variety. As in most of his movies, he was credited as John Merrick. James Seay, who plays the air base commander, is wooden as a plank. He had tiny roles in When Worlds Collide (1951, review), The Day the Earth Stood Still, The War of the Worlds (1953, review). He also had a supporting role in Phantom from Space, and he was at least credited in The Amazing Colossal Man (1957), Beginning of the End, The Destructors (1968) and Panic in the City (1968).

Frank Gerstle and Steve Pendleton were prolific bit-part actors who appeared in both A and B movies, as well as TV series. Gerstle appeared in The Neanderthal Man, The Magnetic Monster (1953, review), Killers from Space, The Wasp Woman (1959), Monstrosity (1963), Murderer’s Row (1966), The Silencers (1966) and The Bamboo Saucer (1968), and Pendleton can be seen in Target Earth (1954, review) as one of the military types stuck in a room. Shepard Menken, as the physician, is actually not that bad in his role, as the only one in the cast emitting anything close to naturalism. Menken soldiered in with bit-parts in B movies up until the mid-fifties, when he almost exclusively switched to TV, and in the sixties he made something of a career in animation voice work. His greatest claim to fame is probably voicing Ricki-Ticki-Tavi in the film with the same name in 1975.

Barbara Bestar as Dr. Martin’s wife does show some emotion, but unfortunately too much, and she overacts all the way through. Bestar played the female lead in four B movies in the early fifties, and spent the rest of the decade as guest actor in a number of TV-series.

Among the smaller bit-part players are a few mildly interesting names to pick up as curiosities. Jack Daly had small roles in The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Rocket Man (1954), Tobor the Great (1954, review), Phantom from Space and Return of the Fly (1959). Ron Gans had quite a time on TV, playing several aliens in the series Lost in Space (1965-1967), the abominable snowman on Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1964-1968), and later started doing voice work – he pops up in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994), and had the honour of voicing the minor Decepticon robot Drag Strip, as well as a number of other voices on the original Transformers TV-series (1984-1987), as well as the straight-to-video movie Transformers: Five Faces of Darkness. X-Men fans might want to take note of the fact that he voiced none other than Magneto in the one-off TV short Pryde of the X-Men (1989). He also had bit-parts in the films The Curious Female (1970), The Thing with Two Heads (1972), Deathsport (1978), Heartbeeps (1981), and Not of this Earth (1988), starring former porn star Traci Lords. Robert Roark’s claim to fame is playing Davis, a psychopathic killer, in Target Earth.

Makeup artist Harry Thomas (the one with the egg trays) did work as part of larger makeup teams on a few A-listers like George Cukor’s Camille (1936) Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956), but the rest of his resumé almost reads like a list of the 50 worst movies ever made. Thomas worked on a total of 21 science fiction films, starting with Superman and the Mole-Men (1951, review), Red Snow (1952, review) and Invasion U.S.A. (1952, review). He then moved on to films like Project Moon Base, Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), The Neanderthal Man (1931, review), Jungle Hell (review), Voodoo Woman (1957, review), The Unearthly (1957m review), From Hell It Came (1957, review), Frankenstein’s Daughter (1958), Night of the Blood Beast (1958), Missile to the Moon (1958), Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957, review), Flight that Disappeared (1961), Space Probe Taurus (1965), Navy vs. the Night Monsters (1966), The Bubble (1966), and The Curious Female (1970). He also worked on many episodes of the TV series Adventures of Superman.

The one thing that stands out surprisingly well in the movie is the music, composed by Manuel Compinsky. A renowned violinist, conductor and music teacher, like many musicians in Los Angeles, he contributed to the film industry, although mostly as a musician. He composed music for three of W. Lee Wilder’s movies, though: Killers from Space, The Snow Creature and The Big Bluff (1955). His brother, Alec Compinsky was music supervisor on Killers from Space, and worked in this capacity on a handful of other films, but most notably on a good dozen TV-series. The music in the film is suitably eerie, with a hint of modernism, and covers long stretches without dialogue.

Janne Wass

Killers from Space. 1954, USA. Directed by W. Lee Wilder. Written by Myles Wilder and William Raymond. Cinematography: William H. Clothier. Editing: William Faris. Music: Manuel Compinsky. Makeup and egg trays: Harry Thomas. Sound recordist: George E.H. Hanson. Starring: Peter Graves, James Seay, Steve Pendleton, Frank Gerstle, John Frederick, Barbara Bestar, Shepard Menken, Jack Daly, Ron Gans, Ben Welden, Burt Wenland, Lester Dorr, Robert Roark, Ruth Bennett, Mark Scott. Produced by W. Lee Wilder for Planet Filmplays.

Leave a comment