This 1952 cold war spy thriller sees Inuit actor Ray Mala battling the Arctic cold of stock footage lifted from half a dozen other films, including his own. A tacked-on plot about a Soviet super-weapon pales next to the great nature (stock) footage. 3/10

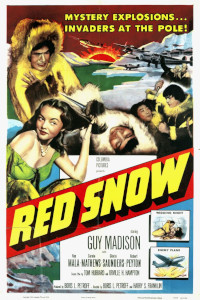

Red Snow. 1952, USA. Directed by Harry Franklin & Boris Petroff. Written by Orville Hampton, Tom Hubbard from a story by Robert Peters. Starring: Ray Mala, Gloria Saunders, Guy Madison, Carole Mathews. Produced by Boris Petroff. IMDb: 6.7/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

It is 1952 and a ragtag team of hardy US soldiers and air force pilots at a snowed-in base in Alaska are keeping tabs on Russian military activity across the ice-covered Bering Strait. Three nights in a row strange lights have appeared in the sky, scaring the local Inuit population (henceforth I will refer to them as Eskimos, as that is what they are called in the film, no offence is intended). The US military have figured that the Russians are testing some new and terrible bomb. Pilot Phil Johnson (Guy Madison) is tasked with tracking a mysterious black Russian airplane that has been appearing over international waters, and is presumed to be Russian, in order to find out what the commies are up to. And on the ground, it falls upon local Eskimo recruit Sgt. Koovuk (Ray Mala) to keep tabs on Siberian Eskimos who have ventured into Alaska in order to find out what they know.

Returning to his igloo-based tribe, Koovuk finds that the weapons testing has afflicted the environment. All sea life has disappeared and his friends and family are starving. They decide to do take a risk and venture over the treacherous ice floes to Russian territory, where they find ample quantities of seals and walruses, but unfortunately also a polar bear, which attacks Koovuk’s wife Alak (Gloria Saunders). All the while, Koovuk keeps vigilant watch over the shifty Tuglu (Philip Ahn), a Siberian Eskimo who claims to have fled from the Soviet Union, but seems curiously interested in Koovuk’s job with the US army. We also visit the other side of the border, and get to know Phil Johnson’s Soviet counterpart, Alex, the pilot of the black plane (John Bryant). When Alex realises that he has been sent on a suicide mission to test one of the super-bombs, he decides to defect mid-flight, much to the dismay of his co-pilot (Bill Fletcher). A struggle ensues in the cockpit, and their plane crashes close to where the Eskimos are hiking. The co-pilot survives and is about to set off the bomb when Koovuk spears him, retrieving the bomb for the US army. But disaster strikes, as the ice floes start crashing into each other, sending the Eskimos on a mad race to save their lives. Lt. Johnson takes off from the base with the aim of saving the heroic Inuits from a certain death, but will he make it in time?

This low-budget Columbia-distributed potboiler also has a “romantic” subplot involving pilot Johnson and US army nurse Lt. Jane (Carole Mathews), which feels hopelessly tacked-on, and a likewise tacked-on comic relief character (Renny McEvoy), whose major pun is putting his chewing gum behind his ear when he speaks to a superior officer. In fact, much of the film feels redundant. The nominal hero and first-billed actor is Guy Madison. But after the initial introduction he completely disappears from the movie as it starts following the exploits of Koovuk and the Inuits, and the only thing remotely heroic he does is swoop in with an airplane picking up the Inuits in the end. The Soviet Eskimo spy Tuglu is also underused, if not wholly unnecessary for the story, as none of his actions have any consequences. Come to think of it, I’m not sure here really did anything in the film. The real hero of the movie is the Soviet pilot who defects, but he only becomes a fleshed-out character five minutes before he is killed in the plane crash.

Red Snow was produced and co-directed by Boris Petroff, a very interesting, and forgotten, writer, producer and director of low-budget movies in the fifties. I first stumbled over him when reviewing the cut-paste pirate/dinosaur job Two Lost Worlds (1950, review) a few months back, and I was able to get a hold of his daughter Gloria (Petroff) Adler, who also appeared in that movie, for an interview. Please head over to my review of Two Lost Worlds if you’re interested in an in-depth read about this fascinating man. To make a long story short, Petroff was a Russian dancer who came to the US some time shortly after the revolution in Russia in 1917. He quickly built up a reputation as a dance teacher and choreographer and in the twenties started to produce pre-movie dance numbers for Paramount’s flagship theatres. It was through Paramount that he met stage and movie star Mae West in 1934, and became her “style adviser” and a member of her entourage — rumours of romantic entanglement followed, but according to Gloria Adler, her father vehemently denied any romantic relationship with West. In 1937 he remarried and ended his contract with West. Petroff had directed a musical film called Hats Off, starring Mae Clarke, in 1936, but didn’t get into movie production proper before 1949, when he produced Arctic Fury, an independent production distributed by RKO.

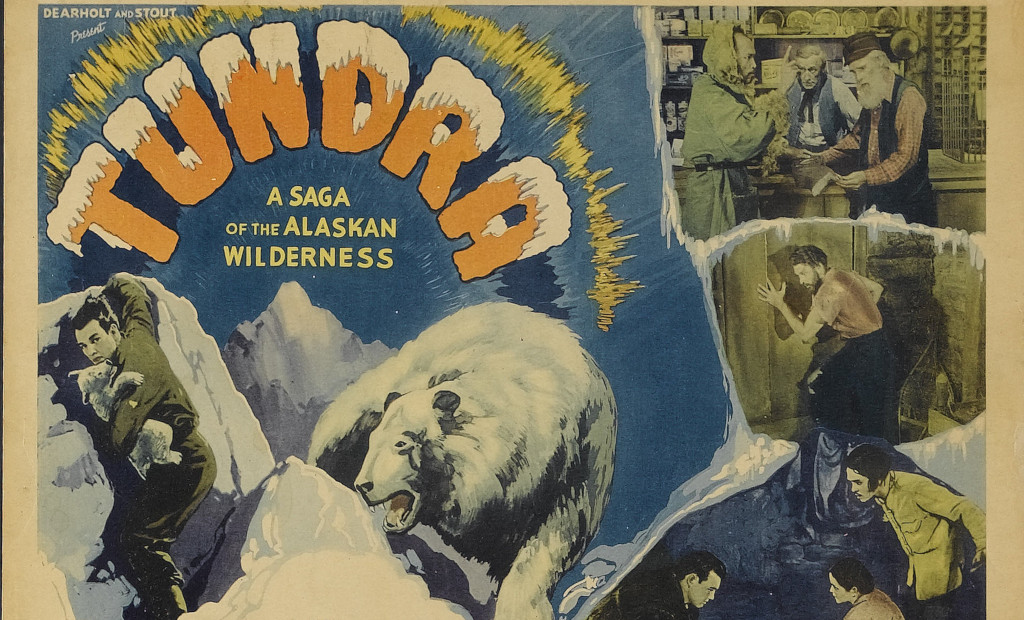

Like Red Snow, Arctic Fury was set in the Arctic areas of Alaska. The film was directed by Fred Feitshans, Jr., a man better known as an editor. In fact, much of Arctic Fury was pilfered from a 1936 film called Tundra, including the main character, around which Petroff and Feitshans build a new background story using new studio footage with other actors, including Gloria Petroff, Boris Petroff’s afore-mentioned daughter. Tundra was meant as an expensive epic at the end of Carl Laemmle Jr.’s era at Universal, but the idea was reeled in when dissatisfaction grew with Laemmle’s “mishandling” of the studio’s finances, and after seven months of location shooting in Alaska, the studio brought the film team home, and filled out the gaps with stock footage, mainly from the 1933 movie SOS Iceberg and the 1926 documentary Alaskan Adventures.

Why am I going through all this? Well, it is because where Red Snow really succeeds is in its superb location shots and its exciting depiction of the adventures that Koovuk’s Inuit tribe go through — walrus hunting, dog sleighing, getting attacked by a polar bear, escaping falling icebergs and trekking through snow storms and dangerous ice floes. This is the actual heart of the movie, and it is great seeing a fifties action adventure film in which the hero is a Native American — played by a Native American (or, Native Alaskan, if you will) — and which actually spends most of its time following its Inuit protagonists. The rest of the story — the pilots, the bomb, the espionage angle — is not only secondary, it is detrimental to the film, as the location and action footage of the Inuit adventure are so much better. And when analysing Boris Petroff’s previous film Two Lost Worlds, I found that pretty much all the action in that picture was footage from other movies, around which a barely coherent plot had been filmed at Hal Roach Studios. And I suspected that not very much of the action in Red Snow was original footage either.

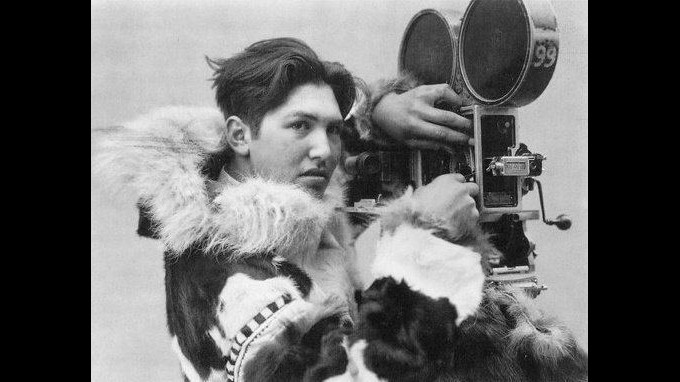

In fact, much of the footage making up the Inuit adventure comes from yet another movie, a film called Eskimo, a high-profile 1933 production by MGM. It was the first US feature film in which most of the spoken dialogue was in a Native American language, and one of the few major studio productions to be filmed almost entirely in Alaska. Based on a book by a Danish explorer, it followed a main character called Mala and the melodramatic story concerned the white traders’ and officials’ atrocities toward the Inuit people and their culture. And in Eskimo, the main character Mala was portrayed by none other than Inuit actor Ray Mala, the hero of Red Snow. And before Ray Mala made Eskimo, he starred in the 1932 docudrama Igloo, filmed on an actual expedition to the Alaskan Arctic. Sold as a straight-up documentary with Mala as a primitive Inuit hunter, the film was in fact scripted, and Mala, who was already working in Hollywood, had accompanied director/adventurer Ewing Scott and a skeleton film team to Alaska. Mala also doubled as a cameraman on the production.

And once Petroff, or Hal Roach, in whose studio Petroff made most of his films, had secured the rights to Eskimo and Igloo, it was probably just a matter of convincing Ray Mala to star in a film where he is doubling for a 20 years younger version of himself. Just write in a few characters appropriate for matching the old footage, copy the costumes and props and: voila! You have your own Arctic adventure film, probably shot over a week in California. As to why Mala agreed to make this film, one reason may be that he simply wasn’t in such high a demand as an actor in 1952. But there’s also a personal reason as to why Boris Petroff might have been able to appeal to Mala. While he grew up in Alaska around the indigenous people, and was himself the son of an Inuit mother, Ray Mala’s father was actually a Russian immigrant, just like Boris Petroff.

I haven’t found a copy of Eskimo, but I found a video showcasing an extensive amount of screengrabs of the movie, and can confirm that most action scenes, the polar bear attack, the walrus hunt and much of the footage showing life at the Inuit village and the trek across the Arctic landscape, are in fact lifted from that film. Neither have I found any copy or even any footage from Igloo, but an article from 1952 in industry magazine Sight & Sound claims that “at least 60 percent of the film consists of footage from the 20-year-old Igloo“. It is quite possible that some of the scenes, in particular those portraying everyday Inuit life, were lifted from this film, although I’d surmise that it’s no more than ten percent, tops. I also watched through Alaskan Adventures and SOS Iceberg, and found the trailer for both Tundra and Arctic Fury. A lot of footage in Red Snow is taken from the second half of SOS Iceberg, in particular aerial footage, shots of airplanes and shots of collapsing icebergs, snowstorms and ice floes. Some of the action sequences seem also to be lifted from the original footage in Tundra. Very little apart from a plot synopsis is written about Red Snow online, so I don’t know if Petroff and co-director Harry Franklin did shoot any location footage at all in Alaska, but knowing Petroff’s usual budget and mode of working, I’d say that I doubt it.

As a standalone film, Red Snow works much, much better than Two Lost Worlds. The script by Orville Hampton, Robert Peters and frequent Petroff collaborator Tom Hubbard is a bit of a mess, but at least it is somewhat coherent. Of course, the problem is that somewhere between half a two thirds of the movie consists of Koovuk’s adventure in the Arctic, with newly shot original material as well as the well-used stock footage. This means that there is little room for any other characters and plot. Koovuk is the movie’s protagonist, but I suspect that in negotiating a distribution deal, Columbia insisted the film have a first-billed white hero and a leading lady for him, as well as a comic relief character. This means we are introduced to Guy Madison and Carole Mathews in the beginning of the movie, as well as to Renny McEvoy, the latter which has no function and whose comedic qualities can be discussed. Madison’s and Mathews’ romance story must be one of the most clumsily tacked-on I have ever seen in a film, and for a leading lady, Mathews is conspicuously absent from pretty much anything that has anything to do with the plot. The actual leading lady of the movie is Gloria Saunders, playing Koovuk’s wife. All the involved actors do a decent job under the circumstances, but that is little comfort when their stories — to the extent that they have such — go nowhere.

We are introduced to a whole slew of US army officials and soldiers, all spending most of their screen time walking through the many doors designed for the two rooms that make up the US air base. I can’t keep track of who is who and what their actual function is, neither why they need to be in the movie. The exposition needed (not much) could very well have been handled between one or two additional characters. It doesn’t help that the Russians also introduce a staff of five or six people to the film, also discussing exposition in rooms pretty much identical to that of the US army’s. Bryant and Fletcher are both pretty good as the Russian pilots, though.

That said, the editing of this movie is very good, just as it was in Two Lost Worlds, and unless you knew, you probably wouldn’t guess that almost all of the action scenes are stolen from other sources. This time Petroff and Franklin work with editor Merrill White, who later earned an Oscar nomination for for his work on The Brave One (1956).

The SF angle of Red Snow is purely a MacGuffin. It is, of course, the super-bomb being developed by the Soviet army. Throughout the entire movie, we remain in the dark about what it is or what it does. The actual plot of the film is Koovuk and his tribe surviving the journey over the Bering Strait, and doesn’t really have anything to do with the bomb. In the film, the bomb isn’t even really a threat, as the Russians don’t seem to have any immediate plans on using it, but rather just test it. And the only way the heros are finally able to come into contact with it is when the Russians manage to crash their own plane. In a clear-cut Hitchcockian scenario, we the audience don’t care one iota about the bomb, it is simply there to motivate the characters of the movie.

For a modern viewer, the on-screen killing of a walrus, and especially a polar bear, can be difficult to watch. If it is any consolation, they were, of course, not killed in the process of making Red Snow, but the 1933 film Eskimo. The scenes are added with some extra realism, as Ray Mala is actually in the scenes with both animals. Eskimo was made as a realistic depiction of Inuit life, and thus the killing of these animals was, in a way, appropriate. Also, back in 1933 these Arctic species were not yet endangered, and killing them were thought of as little different from hunting rabbit or deer. From an modern ethical point of view, the killing of any animal for the sake of producing a film is more or less unthinkable.

Otherwise it is quite inspirational to see Inuit life and culture depicted with such authenticity in 1952 — or 1932 if you will. There are a few caveats to this. Some scenes depict Alaskan Inuits as living in igloos. While many Inuit people did indeed use igloos in the 1950’s, Native Alaskans rarely did so, at least not as long-time habitation, but preferred dwellings made with sod, animal bones and hides. Igloos were still used as temporary shelters, though. And then, of course, there’s the famous “Eskimo kiss”, portrayed in Red Snow as a romantic or erotic gesture. While inuits did and do rub their noses together, it isn’t a romantic thing; Inuits kiss just like the rest of us. The so-called “Eskimo kiss”, or kunik, is a Platonic greeting between family and close friends, a bit like a hug or a kiss on the cheek. Another positive aspect of the movie is that the Inuits haven’t been completely whitewashed in the casting — on the other hand, apart from the uncredited Inuits from the films Eskimo and Igloo, and the other source films from which Red Snow is pasted together, there are no Inuits in the cast, save for Ray Mala and two other uncredited Inuit soldiers. Koovuk’s wife Alak is played by Caucasian actress Gloria Saunders, whose unusual features made her eligible for a number of “ethnic” roles. In the footage taken from Eskimo, she is portrayed by Japanese-Hawaiian actress Lotus Long and possibly Chinese-American Lulu Wong. If any footage of Mala’s girlfriend in Igloo is used to portray Alak, then she might at some point actually be portrayed by an Inuit. The spy Tuglu is portrayed by Korean-American Philip Ahn. Much of the plot and exposition is told in voice-over, as narrated by Koovuk. However, Ray Mala apparently didn’t stick around for post-production, as the narration is done by an actor called William Shaw (doing a pretty good Ray Mala impersonation, though).

In many ways, Red Snow is a very typical cold war propaganda movie. While the communists across the border are portrayed as a war-mongering threat testing terrible weapons, the Americans are all morally incorruptible defenders of freedom and equality. On the other hand, the Russians are less caricatured than in many similar films, and the conversations taking place between the Russian soldiers portray them as normal human beings doing their duty to their commanding officers, with the exception of pilot Alex, who openly rebels against the communist system, in essence sacrificing himself for the “greater good”. Here we see producer Boris Petroff’s hand. While no friend of Communist Russia, Petroff nevertheless took care in all of his movies not to vilify Russia as such or the Russian people, whom he saw as victims of communism just as much as any foreigner killed by a communist bullet. Nevertheless, the final five minutes of the movie, complete with patriotic voice-over and a cavalcade of US air force planes shooting across the screen is as heavy-handed a patriotic propaganda filmmaking as you will ever see, a sort of pompous and obvious propaganda device more common in Soviet movies than US ditto.

Red Snow can be seen as an homage to the Alaska Territorial Guard, commonly known as the “Eskimo Scouts”, active during WWII and consisting mainly of people belonging to several Native Alaskan ethnic groups. Over 6,000 volunteers served in this reserve force without pay. While the unit was disbanded in 1947, there is little doubt that the US army continued to employ the services of many Native Alaskans during he cold war, in official or unofficial capacity. Sadly, the members of the ATG weren’t recognised as a war veterans until 2004, and thus didn’t receive the support other WWII veterans had the benefit of. Today, close to 3,000 of the 6,000+ members of the ATG have been tracked down and honoured.

Another theme of the movie is that of the atom bomb, clearly mirrored in the Soviet Union’s “heat bomb”, as it is explained as at the end of the film. The visual effects of the movie (crude, but effective) do conjure up images of the A-bomb, and the effect that it has on the local wildlife and the Native Alaskan people who starve as their food source disappears does seem like a critique of nuclear testing. Nuclear testing began at the Bikini atoll in the Pacific in 1946. When the firsts tests were made, little thought was given to how the radiation and fallout would affect the inhabitants of the atoll (who still lived there), much less the impact on the environment, mainly because the long-term consequences of nuclear radiation were little understood at the time. This changed with the infamous Castle Bravo test, which yielded a much bigger load than expected, and consequently covered many of the islands in snow-like radioactive fallout. This was the same test that poisoned 23 Japanese fishermen, an incident referenced in the opening scene of Gojira (1954, review). While the residents were thereafter relocated, many were left to their own devices on an atoll lacking housing, infrastructure or sufficient food stock, and as a result the population starved. The US government was harshly criticised in both domestic and foreign press for ignoring the plight of the former occupants of the Bikini atoll. The Inuits starving and being forced to relocate as a result of the Soviet weapons testing in Red Snow can be read as covert critique against the US nuclear tests and the government’s actions in regards to the Bikini atoll and its inhabitants.

Seen with modern eyes, Red Snow also seems to anticipate later environmentally themed SF movies. While the concept of global warming wasn’t a thing in 1952, environmentalists did worry about how the rapidly changing post-war landscape would affect nature and the conditions of people living off the land. The images of melting Arctic ice sheet and the disappearance of the Arctic fauna reverberate strongly with a modern viewer, almost as if bringing issues of global warming to us fifty years before they became a global topic of discussion. Of course, this kind of retrospective analysis is always treacherous, but at least it feels as if someone at the screenwriting table had some environmental issue in mind when writing the script. As an aside: Wikipedia lists this film as written by Karen DeWolf, and omits all other credited writers. I can only surmise that this is a mix-up.

As mentioned earlier, there is precious little written about this film either online or in any of the movie books in my library, so gauging the reception of this film in 1952 is difficult, even if it’s not hard to guess the general outlines. The above mentioned article from 1952 on the increasing use of stock footage in Hollywood in industry magazine Sight & Sound mentions Red Snow as a film where the incorporation of stock material has been “expertly” done. Otherwise, however, the article calls Red Snow “an inept little thriller about espionage in Alaska”. In his 1965 book A Title Guide to the Talkies Richard Bertram Dimmitt calls the movie “a moving picture”.

The only contemporary reviews of Red Snow I can find is a 2/5 star rating at TV Guide and a 5/10 user review at IMDb. TV Guide writes: “Old stock footage of Eskimo life was put to fairly good use in this story […] The performances are as frozen as the landscape.” The IMDb reviewer django-1 writes: “There is not enough cold-war hysteria here to make the film enjoyable on a camp level, and though on some levels it resembles the Sam Katzman-produced serials being made at Columbia during this period, it lacks the over-the-top and absurd elements that made those serials such fun to watch. Except for the Guy Madison fanatic, I can’t imagine this film having much appeal to anyone. It’s not bad— it’s a professional though cheap piece of product, and it certainly shows respect for the native people of Alaska (which should earn it a few points when we think about how offensive it could have been in that department), but I can’t imagine wanting to dig this film out again unless I am stranded above the Arctic Circle myself and all I have with me entertainment-wise is Red Snow“. On IMDb Red Snow has a positive 6.2/10 rating based on only 47 votes.

It is somewhat difficult to pass judgement on a film like this, knowing how it was put together. While it’s clear that Red Snow is not a great film, just how bad you think it is partly depends on how you feel about using stock footage from other movies for something like half of a film, and passing it on as your own. Having now watched two of Boris Petroff’s pictures and researched a third, I can see a pattern emerging. When I saw Two Lost Worlds, I figured that the way the film took its starting point in copious amounts of footage from other movies and built the flimsiest of new story around them was a one-off. It now seems to me that this was the modus operandi of Petroff for the dozen or so films he produced and/or directed and wrote. If I make a home video and splice in a piece of, say, Citizen Kane in he middle, does that make my home video great? Of course it doesn’t, it’s still Citizen Kane that’s a great movie, not the mobile footage shot on my couch. But on the other hand: if you have never seen Citizen Kane, and I match up my own footage with the stock footage so you don’t realize that the segment is taken from another film — will the fact that I did not make Citizen Kane diminish your viewing experience? Of course it won’t. This cut-paste technique wasn’t invented by Boris Petroff, of course, but had been around since the beginning of movies. However, it would become an increasing way of producing films as more low-budget independent operators emerged in Hollywood after the disbanding of the studio system. Roger Corman, for example, would become adept at buying up European SF movies and build new plots around their special effects sequences. It also became a bit of a standard practice for US importers of Japanese SF:s to insert Caucasian “leading men” into the films so as to appeal to US audience — to the point that Japanese filmmakers started to include Americans in the original movies. In this sense, one can view Boris Petroff as something of a pioneer — for good and bad.

Red Snow is certainly better than Two Lost Worlds in most regards. The script is somewhat coherent, even if it feels like there are two separate stories going on here, and as if the Caucasian actors are involved in a hastily cobbled-together story that has little to do with the adventure of Kovuuk and his tribe. But the action and the wonderful location footage are great, even if some sense of excitement is lost due to the fact that the sudden shift to Inuit docudrama has little bearing on the framing espionage story. The studio-bound scenes have a cramped and static feel to them, but they are surprisingly well incorporated into the stock footage of the snowed-in air base. Rear projection scenes are reasonably well handled. I found myself losing interest about two thirds into the movie, despite its little more than ome-hour running time, as it felt that the story wasn’t progressing and had completely lost its focus on the espionage and bomb plot, and the five-minute airplane montage at the end just felt like patriotic padding. Still, despite his low budgets, Boris Petroff had a knack for surrounding himself with a good crew. The editing, as stated, is impressive, the music OK, the cinematography, art direction and direction professional, if hurried and cheap. Unfortunately Ray Mala is stiff as a log, but the rest of the cast is quite alright. Unfortunately, with a script this weak, decent production and acting only go so far. When stock footage is the main attraction of a movie, you’re doing it the wrong way round.

Lead actor Ray Mala was an interesting character. Born as Ray Wise to a Jewish-Russian immigrant father and a Native Alaskan mother in a small village in Alaska, he made his film debut in a bit-part at the age of 14 in 1921, in a film made by an explorer who made a film called Primitive Love. It was also here that Mala got his first gig behind the camera, as he worked as a cameraman on the movie. He then accompanied Danish Arctic explorer Knud Rasmussen between 1921 and 1924 on his trip “The Great Sled Journey”, collecting old Inuit legends and songs, again as cameraman. In 1925 Mala relocated to Hollywood, where he got a contract as a cameraman with the Fox Film Corporation, in which capacity he worked until he got his acting break in Igloo (1932). This led to MGM hiring him for the lead in Eskimo (1933). Despite the somewhat sluggish box office performance of the expensive film, MGM held on to Mala, who received praise for his role and became something of a minor celebrity. In 1935 MGM cast him as a Polynesian in The Last of the Pagans, one in a long line of popular “South Sea Island films” produced from the thirties to the fifties. Like in Eskimo, Mala would henceforth often be credited only by his pseudonym last name, especially in films where he was supposed to play a “primitive native”, partly perhaps because producers thought “Ray” took some of the exoticism away. Rather than Inuit, however, he was most often cast as Polynesian or Native American. He had some success playing the lead in the 1936 serial Robinson Crusoe on Clipper Island (1936) as a Polynesian FBI agent, as well as in the second lead of the serial Hawk of the Wilderness (1938) opposite serial star Bruce Bennett.

He was steadily employed both as an actor and a cameraman throughout the thirties and the early forties, although he soon found himself playing stereotypical “ethnic” supporting or bit parts, sich as in James Whale’s Green Hell (1940). Other SF outings gave him a bit more freedom, especially his role as Prince of the Rock People in the second Flash Gordon serial, Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940), and in the horror SF The Mad Doctor of Market Street (1942, review). Offered mainly bit parts, Mala focused on his job as a cameraman in the forties, a job that went uncredited for the most part, even though he worked on some high profile pictures, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944) and The Fan (1949), as well as Lewis Milestone’s Les Miserables (1952). He often worked as assistant cameraman to Oscar-winning cinematographer Joseph LaShelle.

Sadly, Red Snow became Ray Mala’s last film as an actor, as he died from a heart attack on set as a cameraman in September 1952.

Koovuk’s Wife in Red Snow is played by Gloria Saunders, a starlet of film and TV whose career was almost ended before it had properly begun. Saunders worked as a child actor in radio and on stage in North and South Carolina, and in 1944, only 16 years old, she screen tested for Paramount. But just months later, in 1945, she suffered a car accident, which left her face scarred with a cut from her chin to the forehead. Plastic surgery removed most of the scarring, but she still found it hard to get cast, because of some small remaining scarring above her nose. However, she was able to find work in TV and first turned heads in the recurring role of Ah Toy in the series Mysteries of Chinatown (1949). This wasn’t the first nor the last time Saunders played Asian or Native American roles: she is probably best remembered for playing the mysterious Dragon Lady in the show Terry and the Pirates (1952-1953. Carol O’Dell writes in her book June Cleaver Was a Feminist!: “And if Saunders’ name doesn’t sound very Asian, it’s not surprising. The South Carolina-born actress was as Asian as apple pie*. Nevertheless, she looked exotic enough by Hollywood standards at the time to eke out a career playing a number of “others” — gypsies, Indians, Arabs. Regardless of her heritage, Saunders cut an amazing figure in her role. Supermodel slim, often poured into form-fitting sheathes, Saunders‘ jet-black hair and extravagantly made-up eyes made her a menacing mix of beauty and power.” (*As an aside: the apple actually comes from Asia and was brought to America from Europe.)

Saunders doesn’t have very much to do in Red Snow, other than looking cute and scared, but she does both with grace.

Red Snow was part of Saunders’ attempt at a comeback to the movies following a second round of plastic surgery, now removing any traces of her scars, but despite her now smooth skin, she got stuck in bit parts and “second woman” parts in cheap B-movies. She appeared in another SF film in 1952, the post-apocalyptic Captive Women (review). However, she returned to TV in 1953 and didn’t look back. After she remarried, she left showbusiness in 1960. Sadly, like Ray Mala, she died young, only 52 years old, in 1980.

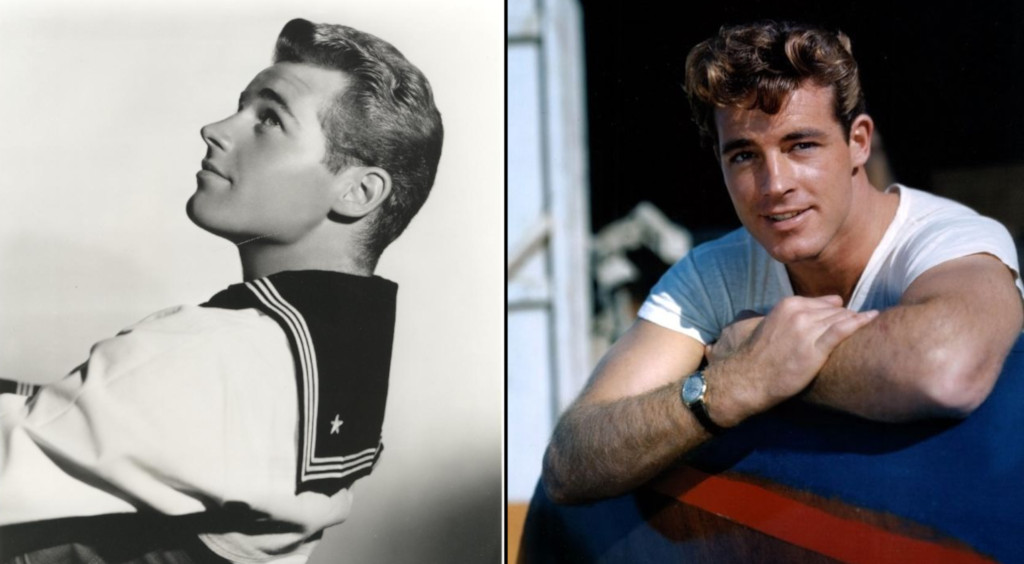

Guy Madison as the “heroic” pilot is adequately swashbuckling in his non-essential leading man role, combining military diligence with a happy-go-lucky bravado. Telephone line man Madison was born Robert Moseley and was literally picked out of the audience when he attended a radio theatre broadcast in Hollywood while on shore leave from the coast guard in 1944. Producer David O. Selznick wanted a handsome sailor for a small but important role in the film Since You Went Away, and his role was filmed over a weekend. The producers made up the pseudonym Guy Madison. Madison’s lonely, handsome sailor struck a nerve with female audiences, and Madison found himself in demand in Hollywood when returning from duty in 1946. Without any acting experience, he took lessons and worked in theatre while at the same time embarking on a successful career as a popular leading man in B-westerns. He secured his immortality among western fans when he was cast in the title role of the long-running TV series Adventures of Wild Bill Hickock (1951-1958), a role which he simultaneously did for radio.

But Madison also managed to secure roles in films both westerns and other genres. Among genre fans he is probably best known for playing the lead in the bizarro western/dinosaur mashup The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956, review). He had a smaller role in the alien drama The 27th Day (1957, review). However, after Wild Bill Hickock was cancelled after seven years, Madison’s career waned, and he moved to Italy for greener pastures, where he embarked on a second career as the star of a long string of spaghetti films, in almost every conceivable genre, including Paolo Bianchini’s SF adventure movies Devilman Story (1967) and Superargo and the Faceless Giants (1968). He also had time to pop over to Germany on a couple of occasions to make movies there. He returned to the US in the seventies and had a large supporting role in the SF family comedy Where’s Willie (1978). He more or less retired in 1979, but returned for the role of Gerrish in a few episodes of the French-British TV series William Tell (released as Crossbow in the US) in 1987 and 1988. William Tell just so happens to be my favourite TV series from childhood and I am thrilled to see that it has now FINALLY been released for home viewing 30 years after it went off air.

Carole Mathews, playing the wholly redundant romantic interest of Guy Madison, was born as Jean Deifel in 1920, and after high school entered a nunnery, until her somewhat older and wiser grandmother talked her out of it, telling her to live a little first — the nunnery won’t go anywhere. In 1938 she went from would-be-nun to Miss Chicago, which won her a screen test in Hollywood. While there, she auditioned for and won a part as a showgirl in the Earl Carroll Vanities, which played in California and Broadway. In Chicago she started studying dance and acting, worked as a radio co-host and took up modelling, and married in 1942, unfortunately without telling MGM with whom she secured a contract the same day — which led to the studio ripping up the contract. In 1943 she secured a contact with Columbia, and divorced in 1944. At first she received mainly bit parts, but she slowly rose in the ranks, securing second leads and even a few leading lady roles in B-westerns.

One of her first large roles was the female lead in the SF serial The Monster and the Ape (1945), and she is also remembered by western fans as the second lead in Blazing the Western Trail (1945). In an interview with Western Clippings, Mathews recalls the serial: “That was just fun to do. It was like not really going to work, it was fun. We wrapped those things up (pretty fast). Ray Corrigan was in the ape suit. He owned Corrigan location ranch in the valley where we shot a lot of westerns. I was glad I knew Ray, because in that costume he was scary.” She was again fired from Columbia in 1945 (allegedly over a row with Columbia’s head hairdresser) and moved to New York to study theatre. She was back in Hollywood in 1949, doing leads in B-westerns and uncredited bit parts in A-movies. With her movie career never really getting off the blocks, like Saunders, she transitioned to the small screen, where she stayed, mainly doing guest spots, until the mid-sixties. However, if her acting career didn’t line her pockets, her business sense did. With a group of fellow actors, she opened a successful restaurant, which sold for a good profit. In 1961 she started working at a travel bureau, quickly becoming its manager. In 1971 she founded her own travel agency, which she sold in 1986 for four million dollars. By that time she had already started running a successful pony breeding business. And thankfully, she got to enjoy a long and comfortable retirement, passing away in 2014.

Odd as it may seem, art director Charles Hall had once been one of the most respected production designers of Hollywood. A staple of Universal from the days of The Phantom of The Opera (1925), he oversaw the design of most of the studio’s classic horror films, he was a favourite of Charlie Chaplin’s, working as production designer on the classic Modern Times (1936). He was twice Oscar nominated. However, in the forties, after working at United Artists, he became relegated to B movies, and even Z movies.

That some original action sequences were in fact filmed as original footage for Red Snow is confirmed by the presence of stuntman Whitey Hughes — who became a veteran of the trade. His career spanned over six decades, and he also appeared as a bit-part actor in at least 130 movies. For SF fans he may be best known for portraying The Baron in Kingdom of the Spiders (1977), a film in which he also worked in the capacity of “stunt gaffer”, which must be one of the more unusual movie credits. His stunt work can be seen in a dozen SF movies, including all the four original Planet of the Apes films, The Omega Man (1971), Logan’s Run (1976), Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) and Men in Black (1997).

Janne Wass

Red Snow. 1952, USA. Directed by Harry Franklin & Boris Petroff. Written by Orville Hampton, Tom Hubbard from a story by Robert Peters. Starring: Ray Mala, Gloria Saunders, Guy Madison, Carole Mathews, John Bryant, Philip Ahn, Tony Benroy, Lee Frederick, Richard Vath, William Shaw, Gordon Barnes, Gene Roth, Robert Bice, Lotus Long. Music: Alex Alexander, June Starr. Cinematography: Paul Ivano. Editing: Merrill White. Art direction: Daniel Hall. Makeup: Harry Thomas. Stunts: Whitey Hughes. Sound: Earl Snyder. Produced by Boris Petroff for All American Film Corporation and distributed by Columbia.

Leave a comment