Arch Oboler’s indie film from 1951 was the first to portray the aftermath of nuclear war. Heavy on biblical reference and weighed down with pompous monologues and slow pacing, the film nonetheless boasts striking cinematography and a gritty, bleak vision of the future. (6/10)

Five. 1951, USA. Written, directed & produced by Arch Oboler. Starring: William Phipps, Susan Douglas Rubes, James Anderson, Charles Lampkin, Earl Lee. IMDb: 6.3/10. Rotten Tomaoes: 63/100. Metacritic: N/A.

If 1950 marked the beginning of the golden age of Hollywood science fiction with the space flight films, 1951 was a year of many firsts. The Man from Planet X (review) was the first feature film to introduce the goldfish bowl alien with his ray gun, and The Thing from Another World (review) gave us the first bona fide alien monster. Later in the year the first benign feature film alien arrived in Washington in his UFO (the first actual alien flying saucer on film) in The Day the Earth Stood Still (review), and the first trip to the hollow center of the Earth commenced on October in Unknown World (review). But in April 1951 Columbia Pictures released the first film depicting the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust in the independently produced Five, something of a great white whale for movie fans for a long time, since in wasn’t made available for home viewing until 2011.

The film follows five survivors of a nuclear war that has wiped out most of the human race, but left all infrastructure and structures intact. Five opens with a succession of mushroom clouds interspersed with images of internationally famous buildings. A young woman with torn clothes staggers zombie-like past a derelict car in the countryside. Vacant and teary-eyed she stumbles through the forest and comes upon a small town, deserted. A church bell starts ringing as she’s desperately pounding on the doors of the ghost town. ”I’m alive, I’m alive!” she screams into the nothingness, finally realising the bell only moves in the wind. At long last she climbs a hill to a small, modern cottage where, to her astonishment, a fire is crackling in the fireplace. Enter a young bearded man with a hunting rifle, and she passes out.

Now we have met our female and male leads, Susan Douglas Rubes as Roseanne, a housewife from Los Angeles, and William Phipps, as Michael, a guide working at Empire State Building in New York. This we get to know as Roseanne slowly awakens from her near-catatonic state, and the exposition is laid out by Michael, who is constantly giving speeches to the skies. It turns out Roseanne was safe from the nuclear radiation in an x-ray room, and Michael was in the elevator at Empire State Building as the bomb fell. Michael is something of a determinist philosopher, and feels that the apocalypse was just retribution for mankind’s folly, and is happy to carve out his own land of plenty and solitude at the cabin, with his new Eve at his side.

Michael’s determination to become the Adam of the new world provides the first strand in the conflict of the film, as he and the four other male survivors of the movie try to come to terms with the idea of a single living female left in the world. Roseanne, you see, isn’t initially keen on jumping into the arms of just any man she meets, be he the last man on Earth or not, which she isn’t entirely convinced that he is. Plus, after Michael has tried to force himself on her, she reveals that she is pregnant, and wants to visit nearby Los Angeles to find out if her husband, or indeed anyone, has survived.

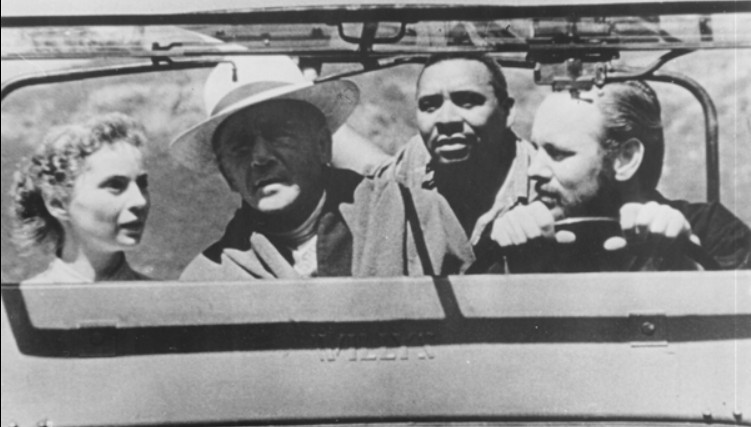

As Michael relinquishes his initial claims on Rosenne, along with the cottage, and starts building a second house, we meet survivors three and four, a Mr. Barnstaple (Earl Lee), and elderly bank clerk, and Charles (Charles Lampkin), a black doorman at that same bank. They are drawn by the smoke of the cottage and arrive by car. Both were accidentally locked in the bank vault at the time of the apocalypse and have been driving around looking for survivors since. Or at least Charles has been looking, since old, sickly Barnstaple is in complete denial and tells himself he is on holiday. They take upp residence in the cottage, and it turns out Barnstaple suffers from radioactive poisoning. Charles falls in beside Michael in tilling the earth and building the new house, while Rosanne cares for Barnstaple and hopes to get the chance to visit the city, while they all ponder over what they have done with their lives, hopes and dreams, realising only too late that they have been existing, rather than living.

At one point Mr. Barnstaple insists on going down to the beach, as he has always loved the sea. The four take a day trip, only to discover the fifth survivor floating in the shallows. They save the unconscious man, who turns out to be Eric (James Anderson), a European adventurer who was stuck on Mount Everest when the apocalypse took place, and has since roamed Asia and Europe looking for survivors, finally flying a plane to America, running out of fuel just off the coast. While they are talking to Eric, Mr. Barnstaple peacefully dies by the ocean he loves. Soon after Roseanne’s baby is born.

Eric becomes the wedge that drives the happy colony apart. After first playing along with the family life, Eric becomes impatient with Michael’s and Charles’ resignation to farm life. Instead he takes the car and starts looting nearby houses for clothes and supplies, including a revolver, which comes into use later in the film. His handsome European charms and his fancy gifts for Roseanne doesn’t endear him to Michael, and it also turns out that he is a racist. Over the course of the film Roseanne warms up to Michael and temporarily seems to accept their new life “together”. But when Eric proposes a trip to New York, she immediately agrees, to the dismay of Michael. Later he is caught stealing supplies by a suspicious Charles, implying that he is not intending to return. Eric stabs Charles to his death before he has a chance of warning Roseanne and Michael.

In New York Eric and Roseanne discover the streets of the city deserted, with the exception of ghastly skeletons lying around in streets, cars and apartments. But will there be any survivors and will one of them be Roseanne’s husband? Will Eric force her to remain with him as a love-slave in this dead city? Or will she return to the cottage and Michael to cultivate the soil, building the the new world together?

I usually don’t want to spoil the endings of the movies I review, but it’s difficult to discuss this one without mentioning the end title of the movie, a quote from Revelations: ”And I saw a new heaven And a new earth … And there shall be no more death … No more sorrow … No more tears … Behold! I make all things new”.

Five was an independent low-budget effort written, produced and directed by Arch Oboler, who had made himself a name in radio, especially with his late night horror program Lights Out, which was brought to TV in the late forties (review). Prior to Five he had directed three movies, including the ill-fated sci-fi film Strange Holiday (1945, review), starring Claude Rains, regarding a man who returns home from a camping trip to find that the country has been taken over by a fascist government. Oboler was known for injecting political and social issues in his radio shows, almost as an educational tool. His fear of an all-annihilation nuclear war can be clearly seen in some of his work, especially in the TV edition of Lights Out, as well as some of the biblical parallels that dominate Five.

This wasn’t the first movie to toy with the idea of the apocalypse or the empty world concept. The Danish moral story The End of the World (1916, review) depicts a cataclysm of meteoric hailstorms, floods hurricanes and earthquakes, ending on a shot of two survivors, the modern Adam and Eve, on a desolate shore by a Christian church. The American comedy The Last Man on Earth (1924, review) mucks around with the idea of a world where a virus has killed off all males in America, save one man. The bombastic French End of the World (1931, review) ends with another meteor shower, but didn’t show life after the fact. Deluge (1933, review) was another film depicting life after a natural disaster. The British H.G. Wells epic Things to Come (1936, review) depicts WWIII and a sort of proto-Mad Max society built on the ruins of war. The Czech film Krakatit (1949, review) shows glimpses of the annihilation of all major cities on Earth by a nuclear-like explosive. That same year also saw Dick Barton Strikes Back (review), which doesn’t so much show an empty world, as much as an empty city where all people have been killed by a secret weapon. Rocketship X-M showed the aftermath of nuclear war on Mars, where a once civilised society has been literally nuked back to the Stone Age. Later in 1951 the world would end in a collision by a rogue sun in When Worlds Collide (review). That film ends with a group of survivors escaping the biblical apocalypse on a modern Noah’s Ark to another planet. But Five is unique in the way it begins after the apocalypse and focuses only on the five survivors trying to get to terms with their new lives, their losses and the tensions within their little family of five.

With a budget of only 75 000 dollars (550 000 in 2015), Oboler snatched up five unknown actors and used a group of recent film school graduates as crew, shipping them all out to his own Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home outside Malibu. This designer cabin functions as the centrepiece of the movie, and about 80 percent of the film is shot in or around it (although the film depicts it as rather smaller than it was in real life). Filmed in black-and-white, as most low-budget efforts at the time, the lack of resources is most visible in the scenes depicting the post-apocalyptic Los Angeles. The town of Glendale was used as a substitute L.A, and we only really see one single street, littered with little other evidence of a nuclear disaster than abandoned cars and the skeletons. Otherwise the low budget isn’t really problematic, thanks to the movie’s remote setting and the character-driven plot.

The film was not an immediate hit with either critics or audience when it first arrived, and contemporary writers described it as slow-moving, naive and pretentious. And despite the fact that the film has since had something of a revaluation, the critique rings true today. The movie is slow-moving and pretentious, although I probably wouldn’t call it naive, as it is a rather cynical look on humanity. More than anything, the movie is bleak, ponderous and extremely talky, even preachy, as most of the characters at some point or other stare toward the sky, delivering monologues. Perhaps the cheesiest moment is when the camera pans over the hills, skies and valleys, while Charles recites the poem The Creation by black American poet and activist James Weldon Johnson. Although it is poignant that this is probably the first time a mainstream audience got to hear African-American poetry on film, the scene, with its biblical gravitas, is hopelessly pretentious. As if we were a bit slow to get the message, Oboler also throws in subtle clues in the form of a dilapidated sign on the wall of the church in the beginning, holding the remains of what looks to have read ”Repent ye sinners”. If the mushroom clouds weren’t enough to drive home the idea, the early images of Roseanne in the abandoned town show newspaper headlines reading ”World organization collapse imminent”, and ”World annihilation feared by scientist”, and the article describes how radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere would kill all animal life. Under it is a rather odd headline reading ”110 000 Chinese living in trees”.

Oboler’s penchant for preaching, and his apparent lack of understanding of this might work detrimentally on his pictures, was apparent already in Strange Holiday. In that movie, Claude Rains’ cringe-inducing monologues were a chore to sit through, and like in Five, the movie hammered home its message by writing it in capital letters on the noses of the viewers. Subtlety wasn’t Oboler’s trademark, and when he made a film about the end of the world, he brought out the full weight of his pathos. And when he did make a comedy, such as The Twonky (1953, review), it should have been clear to all involved that he was not the right person to try and bring the dry, insinuating humour of Henry Kuttner’s and C.L. Moore’s short story to the screen. Instead of the subdued, self-contained satire present in the literary original, Oboler goes over the top with a kind of Loony Toons-style bash bang comedy.

Counteracting the heavy biblical pathos of Five is the gritty, raw and down-beat dialogue. The slow, highly contrasted images are almost Rosselinian, contrasting wide panoramas with intimate, personal close-ups. If Oboler’s other films are anything to go by, the cinematic experimentalism and occasional stark beauty is more thanks to cinematographers Sid Lubow and Louis Clyde Stoumen, also credited as ”cinematographic consultant”. According to interviews with actors and crew, radio pioneer Oboler would often shoot scenes with his eyes shut, and had temper fits when his actors didn’t deliver the lines to his satisfaction, completely ignoring the visuals. Oboler, who worked as an independent, produced, wrote, directed and even acted as art director on the film, was known as a larger-than-life persona with a huge ego, who saw himself as something of an Orson Welles. Oddly enough, none of the two cinematographers wound up known for their cinematography. Sid Lubow primarily worked as a sound editor in TV, for which he was nominated for an Emmy, and Stoumen won two Oscars for his work as a documentary director. Oboler went on to direct a handful of films, including the sci-fi movies The Twonky (1953, review), about a living TV set, and The Bubble (1966). His adventure film Bwana Devil was the first 3D film in colour, and started the first 3D craze in American cinemas.

The sincerity of the script and the strained atmosphere on set help the actors give rather naturalistic performances, with a few exceptions. William Phipps is nondescript, but believable as the philosophical, determined everyman given to bouts of rage. Perhaps the most striking performance is given by Austrian-born Susan Douglas Rubes, playing the simultaneously bewildered and aloof Roseanne, making a very interesting character of what could have been quite flat. One is never quite sure where one has Roseanne, as she seems at the same time helpless and calculating, intelligent and somewhat mentally challenged. Her performance is intense and spell-binding, although she has a tendency towards overacting in emotional scenes.

Best known of the five actors is James Anderson, playing the haughty, racist Eric with the same dry arrogance and low, grating voice that made him a staple as sinister guns for hire in a number of western films and series in the fifties and sixties. There is an enigma and a tension about the character of Eric, that brings some much needed energy to the movie. On the other hand, he does seem more like a movie star caught up in a sincere art film, and thus feels a bit out of place in the film. American reviewers like to call his accent ”vaguely Teutonic”, but there is nothing Germanic in the way that Anderson delivers the lines. Rather, he sounds more like one of those Italian voice actors that dubbed supporting parts in Italian exploitation films meant for the US market from the sixties to the eighties.

The fault for this probably lies with the actor himself, as it is clear that Eric is supposed to represent the Nazi paradigm of the superior race (of course he could have been riffing off Mussolini instead). Eric believes that the reason he and the others are alive is not due to mere chance, but because they are immune to radiation, and he strongly feels that Charles has no place among the new masters of the world that survived the holocaust. The horror he faces in the end when he finds out he is affected by the radiation is just as much the horror of realisation that he is flawed, as the realisation that he is going to die.

Although it went largely unnoticed at the time because of the limited success of the film, Charles Lampkin’s role was a small milestone for African-American actors. Charles in the film is more or less portrayed as an equal member of the small colony, and is given significant screen-time and intelligent dialogue. The only time he is not treated as equal is when attacked by the racist Eric. This was three years before Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge starred together in Carmen Jones, a film that gave Dandridge an Oscar nomination, six years before Dandridge and Michael Rennie caused an uproar by almost kissing in Island in the Sun, eight years before Belafonte played the last man on Earth in The World, the Flesh and the Devil, and 12 years before Sydney Poitier won an Oscar for best actor in Lilies in the Field. That a black actor would receive an equal part in a film inhabited by white actors without playing a valet, nanny, housekeeper or slave was almost unprecedented in mainstream film (a few exceptions existed).

One might argue that the character of Charles was only in the film to raise the question of racism, but I personally feel that is better than taking the route of When Worlds Collide, which doesn’t feature a single black character. Unfortunately Charles is also victim of the long-lasting trope that the black character dies before the end of the film. There are some problems concerning the character, looking at it from a racial point of view, such as the fact that he is portrayed as an asexual character and never seen as either a sexual threat or a presumptive love interest for Roseanne, and that there’s a slight echo of the stereotypical ”noble negro” in the presentation of the character. It is played with such naturalism and dignity by Lampkin, though, that it is difficult to see other racial issues with the film other than those that were dictated by movie industry at the time. And Oboler had such problems with the film, that if he had included an interracial romantic angle he probably never would have gotten it into cinemas.

Most of the extremely small technical and artistic crew only have a handful or a dozen film credits to their names, often in other capacities than those they had on Five. Considering this, it is amazing that the team was able to create such an artistically accomplished and technically sound movie. It is arguably the crowning achievement of Arch Oboler’s movie career, and the praise for this should probably primarily go to cinematographer Stoumen’s sure-footed, documentary style, Emmy-winning editor Ed Spiegel and montage specialist and visual effects creator John Hoffman. The symbolic dissolve and montage sequences are worthy of a Hitchcock film, and the nightmarish scene of Roseanne searching for her husband Steven in the dead Los Angeles, with its blaring civil defence sirens, the Soviet-style rapid editing and the fearless use of mobile cameras is absolutely sublime. There is a fearlessness and experimentalism to the film making it seem more like an experimental art film than anything intended for a mainstream audience. There are rapid zooms, shaky handheld cameras, camera spins and focus readjustments that would make an editorial supervisor tear his hair out. But somehow it all comes together. The soundscape of the movie is wonderfully put together, which is no surprise, considering Oboler’s pioneering work in radio. Five is notable for being the first film where magnetic tapes were used to record dialogue and ambient sound on set, making the sound recording equipment considerably lighter and more mobile than before.

The music is dramatic to the point of absurdity, and sometimes the heavy string sweeps make you feel as if you have eaten a bit too many sugary sweets. The heavy use of biblical images and metaphors easily becomes obtrusive. Exactly what Oboler is trying to say remains a bit unclear, though. The final scene is an utterly tragic one, if one looks at the circumstances. The sympathetic Charles has died, Roseanne’s baby has died, Roseanne and Michael are finally the last two people on Earth, and even their crops are ruined. But still, the triumphant score and the biblical message of a new beginning seem adamant to end the whole business on a positive note. Eden reborn after the scourge of humanity has been wiped away? The enduring human spirit, ever toiling for a better world in the face of utter defeat?

Would the film only be made up of these melodramatic moments, it would be painful to watch. However, it isn’t. In between these moments, Oboler adds beautiful lyricism and even humour. As Richard Schieb of Moria points out, there are scenes that stay with the viewer for their wonderful humanity: ”where Charles Lampkin dances without music on the terrace because the pregnant Susan Douglas cannot stand up to join him; a scene where the characters nostalgically reminisce over the sounds and smells that they miss; where Susan Douglas finally kisses William Phipps but then in the midst of embrace mistakenly calls him ‘Stephen’”. And I would add the death scene at the beach, among a few others.

The aspect of the film that seems most dated today is the scientific one. It is possible that Oboler has taken artistic liberties with the science for the sake of creating a compelling story, but on the other hand, very little was known by the public about how nuclear bombs and radiation actually work. Even the US authorities were only just trying to find out how the damn thing they had built actually worked, and what little they knew was generally suppressed. And this improper science also leads to some logical fallacies.

The movie tells us that all humans on Earth have been instantaneously wiped up by a nuclear war, that somehow still seems to have left buildings and infrastructure completely intact. Even in 1951, this must have come off as absurd, as the one thing people did know about the nuclear bomb was that it was hugely powerful – that’s why it was developed in the first place. And of course, radiation doesn’t kill instantly, so that a whole hospital would be wiped out in a second just from radiation – leaving a single patient in a lead-lined room unharmed is highly unlikely. Deaths from initial radiation is extremely rare, and most people affected by it would be killed by the explosion itself. Plus, a nuclear war on the scale that Oboler is proposing would not only affect humans and animals, but also plant life and soil, and would in all probability trigger a nuclear winter. There simply wouldn’t be any chance for the survivors to till their earth, because it would either be radioactive or decaying because of lack of sunlight and/or contaminated water. And when Michael goes hunting: what exactly does he hunt if all animals are dead?

The crazy science and miraculous coincidences of the film are slightly jarring at times, however, the film isn’t to be taken at face value, but rather as a symbolic piece of art. Of course the idea that the last five survivors on Earth all happening to stumble on each other on the coast of California is nutty, but then this isn’t meant to be a documentary, but rather an rumination in the vein of Samuel Beckett. The problem is that as a writer, Oboler can’t match Becket, and as a director he is no Rosselini. The largest problems are the uneven and often ponderous pace of the film, the monologue-laden script and the biblical preaching. In my book, however, the pros (just barely) outweigh the cons in this one.

Working outside the studio system and the unions, Oboler had considerable trouble getting the film on the market, and finally licensed it to minor studio Columbia to settle the disputes. The bleak, cynical and preachy movie didn’t go down well with critics and the film performed weaker than expected when it opened, despite the fact that it was the first movie that got advertisement on TV.

New York Times critic Bosley Crowther was unusually blunt in his review. So wretched are the five survivors, writes Crowther, that the skeptic might well be tempted to think that it might have been best that the nuclear war would have wiped out mankind entirely: “This impulse to skepticism should not be charged against the nature of man. Rather, it should be charged against Mr. Oboler, who wrote, directed and produced this film. For the five people whom he has selected to forward the race of man are so cheerless, banal and generally static that they stir little interest in their fate. Furthermore, Mr. Oboler has imagined so little of significance for them to do in their fearfully unique situation that there is nothing to be learned from watching them.” He continues: “Obviously, Mr. Oboler, in his manufacture of this film, had some sort of poetic drama or social allegory in mind. For the mood is solemn and ethereal, the pace is portentously slow and the pictorial details, while literal, are blandly illogical. It takes Mr. Oboler a long time to get from here to there, so randomly does he get his camera wander over sea, sky, clouds and hills […] Furthermore, he has charged his actors, all of whom are professionally obscure, to play in a stiff, monotonous style.”

Variety was a little more forgiving in its review: “Intriguing in theme, but depressing in its assumption. Five ranks high in the class of out-of-the-ordinary pix. […] Writer-producer-director Arch Oboler has injected vivid imagination into the production, but draws a little too much on his radio technique. Principal criticism lies in its dearth of action. However, interest is sustained in suspenseful situations and convincing dialog.”

While falling quickly away from cinemas, the movie was quickly repackaged with new marketing material by Columbia, and enjoyed a minor success as a late-night movie later in 1951. It was then loved by film viewers in the sixties and seventies, when it was often run TV, but after that it sort of fell off the grid, and it wasn’t until 2011 that it was released for home viewing, and has since garnered something of a cult following among cinephiles and SF fans.

Five has been cited as a major influence on George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, and its bleak vision of nuclear holocaust influenced movies like The World, the Flesh and the Devil and On the Beach (1959), among others, not least Roger Corman’s The Day the World Ended (1955, review), which could even be called a rip-off.

Still, the movie has a patchy reputation with modern critics as well. TV Guide gives it 2/5 stars, calling it “a heavy-handed end-of-the-world film”, and it it receives 2/5 stars as well from Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum, who criticises its slow pacing. Mark David Welsh echoes the sentiment: “There’s an obvious ‘Garden of Eden’ parallel here, and, unfortunately, as the film progresses, it’s rather layered on with a trowel. But it’s the lack of action that really sinks the film. It’s very talky indeed and, although this is quite realistic, and very different to all the mutations and monsters that were shortly to follow, inevitably it’s not very exciting.”

In his book Keep Watching the Skies, film historian Bill Warren has this to say about Five: “Five might be considered the first science fiction Art Film , in he worst senses of the term. It’s gloomy, talky, low-key, flat and preachy. The actors are amateurish, the photography is grainy, harsh and pretentious. The film is not a disaster, however; it’s storyline makes the movie reasonably interesting.”

Richard Scheib at Moria is rather more forgiving, awarding the film 3/5 stars. And Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings also gives Five a thumbs up: “it has a lot of talk, but the talk is fascinating, tragic, touching, and always holds my attention. […] Plotwise, it is a little predictable; if someone gave you a list and a description of the survivors and told you how many of them would be alive at the end, you’d probably be able to figure out who without any problem. […] Whatever flaws this movie has, it is powerful and memorable.”

French site DevilDead praises the film’s “sense of desolation and confinement that was very unusual for American cinema”. Gene Triplett at The Oklahoman writes: “Relentlessly humorless and long on high-minded debate over the finer moral points of survival and responsibility in the atomic aftermath, the film is nonetheless well-acted, effectively atmospheric and interesting”. Triplett calls Five “one of the best of the early post-nuke-holocaust yarns to reach the big screen”.

Alan Bacchus at Daily Film Dose is very positive in his 3.5/5 star review: “The film requires some patience to get through a sometimes tediously slow first and second acts. But when the villain emerges and conflict becomes dangerous for the survivors, Oboler’s third act is so uncompromising, so unHollywood in comparison to any other film of its day it will leave a lasting impact. […] Few films, if any, in this genre were made with this kind of thematic depth back in 1951.”

Lead actor William Phipps was a theatrical actor who at the time of Five was working steady in Charles Laughton’s acting troupe. In film he had a small number of small parts under his belt, including the voice role as Prince Charming in Disney’s Cinderella (1950). He would go on to act in a number of sci-fi films in the early fifties; he had small roles in The War of the Worlds (1953, review), Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), Invaders from Mars (1953, review)and Oboler’s The Twonky (1953, review). Phipps also narrated the TV version of Dune (1984). In an interview with Tom Weaver he said that he never sought out science fiction, but the films just fell on his lap in the fifties. He does say that he likes science fiction in general, but thought Arch Oboler’s films were rubbish. Phipps was a respected character actor who spent much of his career (outside of the stage) doing guest spots in close to 200 TV shows, all the way up to the year 2000, when he retired and enjoyed 18 years of retirement before passing away in 2018, then the oldest living actor to be primarily associated with science fiction (As of 2020, that honour goes to June Lockheart, matriarch of the original TV series Lost in Space).

Broadway actress Susan Douglas Rubes is quoted as having been difficult on set and didn’t get along with co-star Phipps. Outside of her theatre career she mostly appeared on TV, best remembered for playing Kathy in the long-running series The Guiding Light between 1952 and 1962. She continued her successful theatre career in Canada, where she worked with youth theatre and founded the Young People’s Theatre in Toronto, was at one time head on the CBC radio drama unit, became president of the Family Channel, and served on a number of cultural councils and boards. She passed away in 2013.

James Anderson also appeared in Donovan’s Brain (1953) and I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). He is best known, however, for his role as Bob Ewell in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962). His last film was Little Big Man (1970).

Charles Lampkin was a pioneer in Spoken Word in the thirties, an actor, composer, musician and scholar. In later years he became a teacher and professor, teaching both acting and music, with emphasis on black musical heritage, as well as African-American poetry. It was Lampkin himself who convinced Oboler to include an excerpt of Weldon’s poem The Creation in the film. He acted in over 100 films or TV series, mostly in TV. His only other sci-fi film was Ron Howard’s feelgood drama Cocoon (1984), but he appeared in a number of sci-fi TV series, such as The Wild Wild West (1968), The Incredible Hulk (1978) and Street Hawk (1985). Five was his first foray into film or TV.

Despite Earl Lee’s respectable age, Five was his first feature film and he appeared in 24 other films or TV series in his career, none of them especially well known.

If you are having trouble finding the film, it may be because in 2011 some marketing genius went and renamed it 5ive when it was released on DVD.

Janne Wass

Five. 1951, USA. Written and directed by Arch Oboler. Starring: William Phipps, Susan Douglas Rubes, James Anderson, Charles Lampkin. Music: Henry Russell, William Lava, Charles Maxwell. Cinematography: Sid Lubow, Louis Clyde Stoumen. Editing: John Hoffman, Ed Spiegel, Arthur Swerdloff. Art direction: Arch Oboler. Sound: William Jenkins Locy, Gus Bayz (special sound effects). Produced by Arch Oboler for Arch Oboler Productions.

Leave a comment