Preparing for a potential nuclear winter, a team of scientists test the theory that the Earth is hollow, in this 1951 cheapo from visual effects wizards Jack Rabin and Irving Block. Loosely based on Verne and Burroughs, Unknown World has the makings of a good film, but stumbles in all departments.

Unknown World. 1951, USA. Directed by Terry O. Morse. Written by Millard Kaufman. Inspired by novels by Jules Verne & Edgar Rice Burroughs. Starring: Bruce Kellogg, Marilyn Nash, Victor Killian, Otto Waldis. Produced by Jack Rabin & Irving Block. IMDb: 3.9/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Released two years earlier, Unknown World might have become a minor cult classic, so novel was its idea in Hollywood at the time. But released in late 1951, the movie faced such stiff opposition from other science fiction films, like The Day the Earth Stood Still (review), Superman and the Mole-Men (review) , When Worlds Collide (review) and Flight to Mars (review), that it was overlooked. And unfortunately it hasn’t received the same sort of delayed appreciation as other cult classics either. The main reason being that it is neither very good nor campy enough to be loved by the so-bad-it’s-good fans. But for any completist sci-fi fan it is definately a must-watch, since it is the first full-length feature film to tackle the Hollow Earth genre.

The movie was written by Millard Kaufman, who would later become one of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s top screenplay doctors, although his work mostly went uncredited. However, he was nominated for Oscars twice, which is a bit difficult to believe when watching this movie. Unknown World is basically two parts Jules Verne, one part Edgar Rice Burroughs and two parts Kaufman.

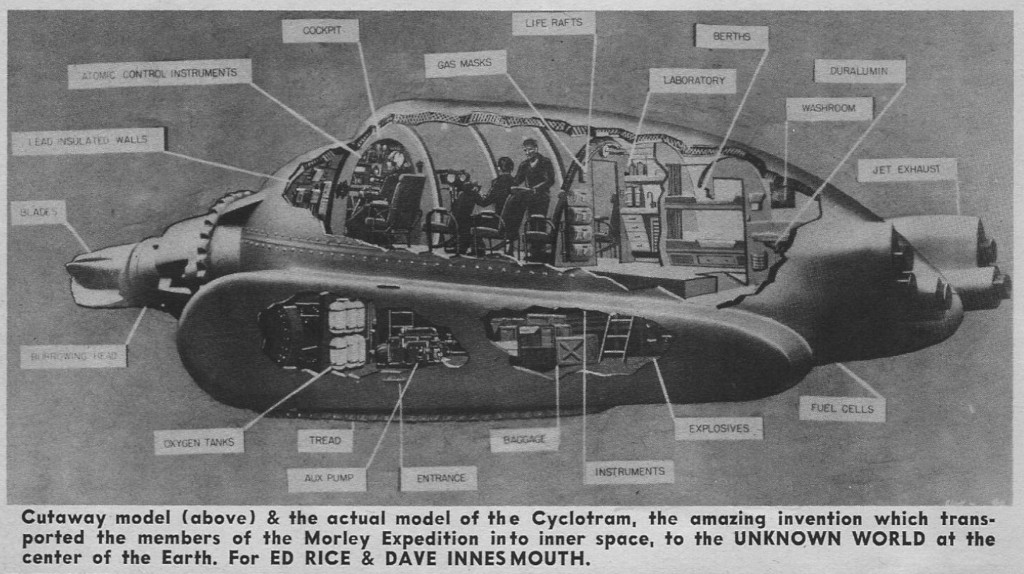

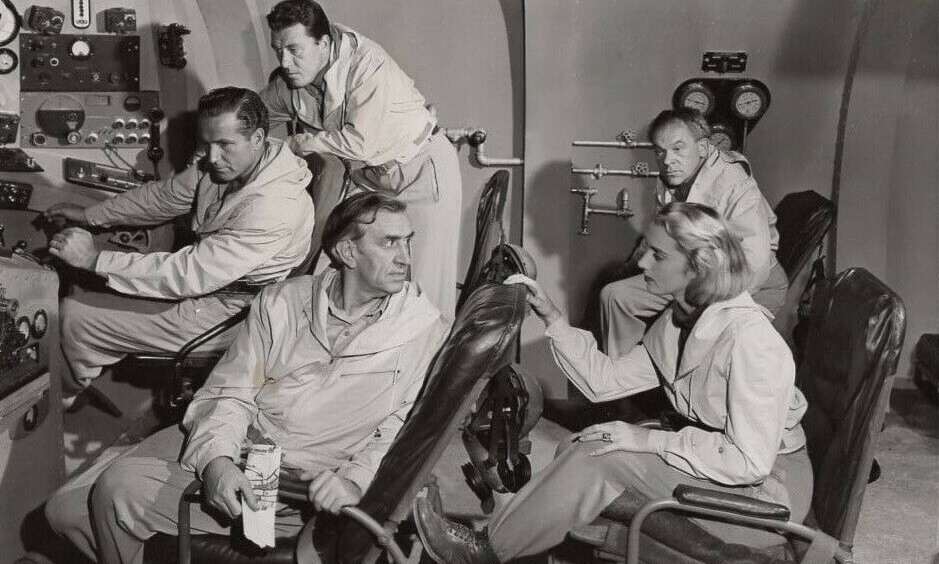

Unknown World opens with a ten minute long newsreel, Citizen Kane-style, telling of Dr. Jeremiah Morley (Victor Killian), the resident egghead of the film, and his futile efforts to get funding for a subterranean exploration trip to find a cave capable of sustaining life after a nuclear holocaust, which he believes is imminent. The trip would require substantial funds, since the explorers need to build a ”cyclotram”, or a super-scientific cross between a submarine, a tank and a drill. The newsreel also conveniently presents his team of five, including German defector and geologist Dr. Max Bauer (Otto Waldis) and biologist, medical doctor – and ”ardent feminist” – Dr. Joan Lindsey (Marilyn Nash), and a couple of disposable characters played by Jim Bannon, Tom Handley and Dick Cogan.

Turns out the newsreel is shown at a private screening, and the audience are the explorers themselves. The projectionist is millionaire playboy Wright Thompson (Bruce Kellogg), son of a media mogul whose papers have slandered Morley’s expedition and his fear of nuclear war. To everybody’s surprise, the wayward son is willing to finance the whole expedition out of his own pocket, on the condition that he comes along for the ride. This is met with skepticism, as the team doesn’t think that this broad-shouldered young, athletic man in seemingly prime health has what it takes to make such a demanding trip, as opposed to some of the geriatric scientists starting to grow a bit round in the middle. Unsurprisingly, the protests are quickly silenced.

We then cut to the future, when the cyclotram is built and the team arrives in Iceland (hello Jules Verne), where they start their journey down the crater of a volcano. The cyclotram is evidently based on the drill in Burrough’s At the Earth’s Core, but the following action is taken from A Journey to the Center of the Earth. In Verne’s novel, the three explorers were on foot, but apart from that, the journey follows much of the same outlines. The explorers set about their task with rigorous scientific calculation, they at one point search desperately for water, despair when they think they’ve reached a dead end, marvel at the wonders of the underworld and the beauty of nature, get depressed by the dark loneliness, get knocked out by poisonous gas and eventually make it to an immensely vast, illuminated cavern with a great big sea, all outlined in the book.

However, Kaufman leaves out the dinosaurs and giants, and instead keeps the whole thing strictly realistic (within the fantstic parameters of the setup). In fact, instead of giant life, they find death, as the lab bunnies they brought along deliver stillborn babies. After an autopsy they conclude that the bunnies have been rendered sterile, and conclude that all things in the cavern would end up the same. This would thus not be a haven for humanity, as no children could be born here, the remaining team who haven’t died on the way conclude – all but Morley, who still feels that the last humans on Earth could find a haven for the last years of their lives after a nuclear war – perhaps science would find a way? But the others argue that this cave, this dead end, is just the dead end of their own making. They try to find ways to run away from the horrors of humanity, hiding in caves, instead of fighting for what is good and right on the surface. The world is too beautiful a place to be left in the hands of those that would destroy it, while those who would cherish it are too afraid to take a stand … Whatever the future hold, the team must now return, but problems arise when the tunnels are shaken by an earthquake … will they make it back to the top? Cue dramatic music.

Kaufman also adds his own personal drama to the screenplay, which is what mostly drags the script down. The battle of egos between playboy Thompson and a young member of the team ends up in fistfights so many times that it becomes laughable. As so often in these films there is a tacked-on romance that feels so strained that you’re afraid the film might get an aneurism. And once again, just like in previous films I’ve reviewed, like Rocketship X-M (1950, review), there’s the nauseatingly chauvinist debate over whether a female scientist – and a feminist at that – can be anything but cold, calculating and ”unfeminine”. And just like in those films, what she really needs is a man’s man who can see through all that feminist crap and make her realise that what she really wants is to be wooed by a real man who can treat her like a real woman.

Nevertheless, the script is not without its shining moments. For one thing, it never winks at the audience or plays it for cheap thrills. The film remains deadly serious throughout and never relents its bleak cynicism. Some of the more philosophical discussions are quite intelligent and even moving. There is a moment when a giddy Thompson presents Dr. Lindsey with beautiful objects he’s found in a cave, only to be flatly told by the geologist that they will turn to dust as soon as he takes them to the surface. Thompson’s childish indignation and frustration over a world where pearls are mere carbon dust and flowers crumble like sand is very touching. Thompson also goes through a believable transformation from arrogant dickhead to a decent person working for the greater good when the team member he’s been squabbling with sacrificies himself for Thompson. You don’t often see these kinds of transformations in low-budget features like this from the era. The tone of the film is indeed much closer to the ponderous anti-nuclear allegory Five (1951, review) than, for example, the later lush Technicolor adaptation of Verne’s book.

One of the problems of the film is the science, and the apparent stupidity of these supposedly brilliant scientists, a common problems in films like these where the characters have to give the audience a lot of information and need to have mistakes made to keep the story moving. There’s so many problems with the actual science, that they can’t all be listed, and one has to take films like these with a good dose of suspension of disbelief. I can buy that the Earth never gets warmer and the pressure or gravity never builds up, although they travel 3 000 miles down, and that there is perfectly breathable atmosphere in those caves – those are liberties one has to take with films like these. But the small things – like the water tank getting polluted by poisonous gas because someone left the the air valve open? These guys designed a waterproof submarine-tank, but couldn’t make a water dispenser with a one-way valve? Please. And the fact that they can’t find any water – tell me – have you ever been in a dry cave? Just lick the rock. Deep sea fish 1 000 miles beneath the surface? How did they get there? What do they eat?

The film was produced by Poverty Row studio Lippert Pictures, the studio that also produced the surprisingly good Rocketship X-M, and the team also seems to have made quite an effort to make this film as good as they could. There’s never a feeling of it being an exploitation programmer – the studio has actually made an effort to make a classy picture with substance and a message. Unfortunately the lines come off cheesy a few times too many, and it isn’t helped by the fact that they are lines like ”I was always afraid of love”, and that director Terry O. Morse have shot the actors squinting up into the skies (well, rock-ceiling anyway) delivering their lines like profound wisdoms. Morse was best known as an editor, but also directed a fair number of B movies. He is best known for directing the American add-ons that turned Gojira (1954, review) into Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956, review). He edited the Jack Arnold film The Space Children, the surprisingly good Ib Melchior/Byron Haskin collaboration Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964) and Panic in the City (1968).

The cinematography is a mixed bag. There are way too many shots of the actors standing in a group talking against a matte backdrop or some rock wall, which makes for a very static feel. The black-and-white movie suffers from an abundance of dull grey due to the cave setting. On the other hand, the caves look fairly realistic, partly thanks to the fact that much of the film was filmed in quarries, canyons and the Bronson Caves in Californa, which were used in many Hollywood films. There’s also some terrific second unit photography of the limestone caves of Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, helped by beautiful lighting. All the rock does help to create a feeling of isolation, but all the caves they roam are big as cathedrals, and cramping the spaces a bit would have made for a more claustrophobic movie. Cinematographers Henry Freulich and Allen G. Siegler were B movie specialists without any big films to their names.

The special effects of the movie were designed and executed by Jack Rabin and Irving Block, who also acted as producers on the film. Rabin and Block had started their sci-fi collaboration on Rocketship X-M and continued on Flight to Mars, and would go on to become B movie legends in the fifties, see more about their work in the review of Flight to Mars. They were helped out on Unknown World by Menrad von Mulldorfer, who also made the effects for Kronos (1957, review). However one of the biggest flaws of the film is the cyclotram, that looks way too much like a plastic toy when filmed in motion. The matte work is well done and at least from the print I watched it was sometimes difficult to tell where a matte ended and reality begun. Willis Cook who also worked on The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review) and Cat-Women of the Moon [1953, review] did the mechanical effects – the drill of the cyclotram and the gauges and gadgets in the vehicle, which are not bad.

Composer Ernest Gold won an Oscar and a Grammy for his music in Exodus (1960) and a Golden Globe for the dystopian sci-fi movie On the Beach (1959), as well as a Laurel award for It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963). In Unknown World he is a bit off kilter, though, trying to create eerie cave music from some instrument that I can’t quite place but sounds like a mix between a flute and an organ and comes off as a stoned hippie trying to tune his pan-flute. His music from Exodus can be heard in a sample in Moby’s song Porcelain.

The acting is almost uniformly bad, perhaps with the exception of Otto Waldis. Waldis was a German immigrant, who mostly did B films, but had stints in A movies like Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) and Judgement and Nuremberg (1968). He also appeared in The Night the World Exploded (1957, review) and Attack of the 50 Foot Woman (1958). Victor Killian was a prolific character actor in the thirties and forties, and pulls off a decent job as the head scientist in the film, but one does get the feeling that he’s in a bit over his head trying to carry the movie on his shoulders and not getting much help from his co-stars. Killian was a leftist who got blacklisted for his opinions during the production of the film, and therefore received no screen credit for his role. He returned to stage acting in 1952 and guest starred on TV in the sixties and seventies. The less said about the rest of the actors, the better.

Marilyn Nash only appeared in two films — but did go on to stage and tv roles, and later worked as a casting director. In an interview with film historian Tom Weaver (who’s book titles are so long that I get tired of citing them), she readily admits that her performance in Unknown World is not particularly good. She blames this on director Terry Morse and producers Rabin and Block, all three of which, in her opinion “didn’t have any talent”. Nash was supposed to become a doctor, but caught the eye of Charlie Chaplin when vacationing in Los Angeles. Chaplin put her on contract, and she appeared in Monsieur Verdoux (1947). However, as Chaplin’s movie projects were few and far between, she left him after three years of waiting to go freelance, which she in hindsight regretted. She tells Weaver she wasn’t particularly interested in doing Unknown World, “but I had to do something!”. As an inexperienced actor, going from being directed by Chaplin to a low-budget SF movie was naturally tough, and to Weaver Nash complains that the actors had no chance to rehearse, got no direction from Morse, and weren’t even shown concept drawings of the cyclotram or the matte paintings, so she had no idea what to react to on camera. She said she was “horrified” when she saw the movie.

Unknown World received mixed to negative reviews upon opening. Variety, often rather gentle on these types of films, wrote that the film “carries sufficient interest and exploitation potential” and “neatly carries through its fantastic premise and is materially aided by some fantastic process photography” (this, at least, Block and Rabin knew). Hollywood Reporter, long averse to science fiction because “it’s impossible and could never happen”, called in “inconclusive” and “preposterous”. Monthly Film Bulletin labelled it an “unusually childish piece of science fiction”.

Today Unknown World has a somewhat mixed reputation. Phil Hubbs at Hubbs Movie Reviews gives it a solid 7/10 stars: “Naturally the effects are limited and quaint but still utterly charming. […] Of course the science is silly and of course it’s all very hokey, but movies like this paved the way for your modern-day blockbusters. […] Just a shame there weren’t any monsters, this movie actually took a more intelligent route, surprising really.” Another defender of Unknown World is Richard Scheib at Moria, who awards it 3/5 stars, and, unlike Hubbs, is happy that there is not “a single optically enlarged lizard to be found anywhere in the film. Instead, the film is an oppressive journey into darkness”. According to Scheib, “For a zero budget 1950s lost world effort, Unknown World achieves some unexpectedly good things”. He cites the gloomy and downbeat atmosphere, comparing it favourably to many of the up-beat SF movies of the fifties.

Justin McKinney at The Bloody Pit of Horror matches my rating with 2/5 stars: “Though this film is patently absurd from a scientific standpoint, if you’re just looking for a mild sci-fi adventure you can turn your brain off to and pass an hour with, this will do the trick about as well as anything else. It’s sometimes sluggishly-paced, very talky and boasts some pretty lame model effects (especially the toy-looking Cyclotram), but there’s just enough plot complication to keep it going.” Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings writes: “the script is weak, and the acting is uneven. It’s fairly dull for the most part”. And Films in Boxes, with its 1/5 star rating is no kinder: “Oh goody. Another tepid 50’s movie about people who explore a soundstage. Sure can’t get enough of these bad boys.”

In his magnum opus Keep Watching the Skies!, film historian Bill Warren writes the he wished he could like Unknown World a little better than he does, and after watching and re-watching it a couple of times, I have the same feeling. There’s a lot of stuff to like here, like the sincerity of the filmmakers and the naive childishness with which they present their proposal for a better world. It is made by seasoned professionals and the skill behind the lens is apparent in short flashes of majestic caves and back-lit mountaintops, beautiful matte paintings and crisp images of dripping stalagtites. There’s the occasional profundity hidden in the clunky dialogue and rare moments of creative camera use. But time ran out, money ran out and talent ran out. The script IS clunky and pretentious and un-scientific and illogical and absurd. The cyclotram DOES look like a plastic toy and has a small drill that could never make a hole big enough for the whole thing to go through. The editing IS bad and the acting IS appalling. The pacing is off, and I usually find myself yawning loudly before the first half of the film has passed.

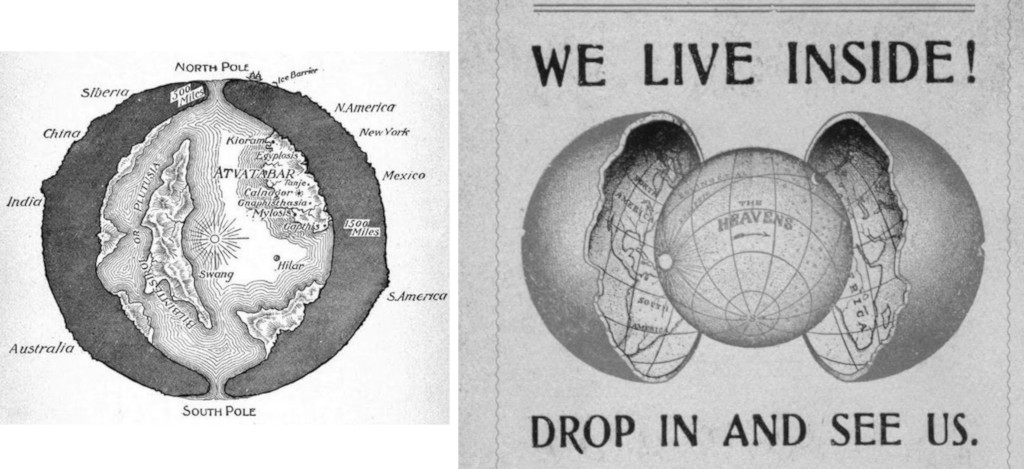

As mentioned above, the film draws inspiration from the so-called Hollow Earth theory — a pseudoscientific theory that had its heyday from the 17th to 19th centuries, and proposed, obviously, that the Earth was actually made up of a fairly thin crust and was hollow inside. The theory has its roots in myth and religion. Many mythological sagas and epics either depict or allude to an underground world, often connected with death or some kind of monsters and demons. One of the most famous depictions is of course found in Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, written in the 14th century, but Ancient Greek mythology describes the Underworld or Hades, where the dead must travel, and old Norse mythology tells of Hel, at one point described as existing beneath the roots of the world tree Yggdrasil. Many tribes in Asia and the Americas also have myths about ancestors emerging upon Earth from dwellings underground. Many early religions and cultures describe the world of the dead as being located underground. The Epic of Gilgamesh, from at least as far back as 6,000 BC, describe Gilgamesh visiting the Land of the Dead in the bowels of the Earth, and Christian mythology refers to Jesus “descending” into the realm of death before “ascending” to the heavens.

The scientific theory of a hollow Earth gained speed in the late 17th century, and although it was almost immediately disregarded as unscientific nonsense, the theory actually still has some defenders even today. I would love to get them together with the flat-earthers. The idea, in short, was/is that the Earth’s core is not a molten mass of metal and mineral as conventional science would have it. Instead Hollow Earth proponents would have us believe that the Earth is actually – well, hollow – and often inhabitable. Different theories abound. Some have claimed that the Earth simply has a big hole in he middle, others that the hole also has a sun inside of it. Others mean that there is a smaller sphere inside the hole, or even different levels of ”crust” with layers of air in between. There’s also a theory of a concave hollow Earth, which states that we actually live inside the Earth and only believe we live outside due to an optical illusion.

Fictional stories of a Hollow Earth were likely sparked by a renewed interest in the theory in early 19th century, when the theory’s best known proponent John Cleves Symmes was widely publicised. Symmes proposed that the Earth had a thin crust and a hollow center, and that one could reach the center through holes at the North and South poles. So convincing was he that US president John Quincy Adams almost approved of a state-funded exploration trip to the North Pole to find the entrance to the underworld. Unfortunately he was beat for re-election by Andrew Jackson, who would have none of the silliness.

Ludvig Holberg, Giacamo Casanova, ”Captain Adam Seaborn”, Edward Bulwer-Lytton and others wrote modern novels about hollow Earths in the 18th and early 19th centuries. One of the most inspiring accounts came from Edgar Allan Poe in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838). Inspiring, perhaps, because he ended the novel just as his protagonist enters the entrance to the underworld. The novel was an inspiration for Jules Verne when he wrote what is considered as the blueprint for hollow Earth fiction: A Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) – although it actually doesn’t promote the hollow Earth theory, but rather speaks of an enormous cavern closer to the surface inhabited by giants and prehistoric creatures. The protagonist of the book does, however, use many of the pseudo-scientific arguments that hollow Earth proponents use to argue that the Earth has a cool core and can be traversed via volcanic tunnels – unfortunately the explorers get shot out through a volcano before they reach the center of the Earth. The most famous novels dealing with an actual hollow Earth are the seven books in Edgar Rice Burrough’s sci-fi/fantasy Pellucidar series, with the first book At the Earth’s Core released in 1914, two years after his seminal two stories about John Carter and Tarzan.

Today the Hollow Earth theory has been overshadowed by the Flat Earth theory, but it still has a few proponents, although they are few and scattered.

Janne Wass

Unknown World (1951). Directed by Terry O. Morse. Written by Millard Kaufman. Inspired (uncredited) by A Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne and At the Earth’s Core by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Starring: Bruce Kellogg, Marilyn Nash, Victor Killian, Otto Waldis, Jim Bannon, Tom Handley, Dick Cogan, George Baxter, Harold Miller. Music: Ernest Gold. Cinematography: Henry Freulich, Allen G. Siegler. Editor: Terry O. Morse. Procuction design: Jack Rabin, Irving Block. Set decoration: Glenn P. Thompson. Makeup: Kiva Hoffman. Production supervisor: Glenn Cook. Sound engineer: Harvey Henry. Special effects: Willis Cook. Visual effects: Jack Rabin, Irving Block, Menrad von Mulldorfer. Produced by Jack Rabin & Irving Block for Lippert Pictures.

Leave a comment