A scientist receives messages from Mars, and the sender appears to be Jesus Christ himself. However, it is all a commu-nazi trick to destroy Western capitalism. Or is it? Would this 1952 red scare film not have taken itself so utterly seriously, it might have been fun. 1/10

Red Planet Mars. 1952, USA. Directed by Harry Horner. Written by John L. Balderston & Anthony Veiller. Based on play by John L. Balderston and John Hoare. Starring: Peter Graves, Andrea King, Herbert Berghof, Walter Sande, Marvin Miller, Morris Ankrum. Produced by Donald Hyde and Anthony Veiller for Melaby Pictures Corp. IMDb: 4.9/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 40/100. Metacritic: N/A.

Progressive scientist Chris Cronyn (Peter Graves) and his deeply religious, doomsday-fearing assistant/wife Linda (Andrea King) discover messages from Mars with the aid of their ”hydrogen valve”. At the same time astronomer Dr. Mitchell (Lewis Martin) confirms the theory that the canals on Mars are irrigation channels and that the Martians have a fantastic irrigation system, far beyond anything existing on Earth, able to melt and regenerate their polar ice caps with incredible speed. This invigorates Chris and frightens Linda.

However, although they have been sending messages back and forth, the Martians and the Cronyns haven’t been able to communicate because of the lack of a common language. The solution comes from one of their two sons, Stewart (Orley Lindgren). While eating pie, he suggests using Pi as reference. Brilliant, says Chris and Admiral Bill Carey (Walter Sande). A civilisation as advanced as the Martians’ must have wheels, and to make wheels you must know how to make a circle – ”And you can’t make a circle without knowing the ratio of the diameter to the circumference – Pi”.

Said and done, the Cronyns work out a way to communicate with Mars, although not without some bouts of hysterical fits from Linda, spouting lines like ”And you’ll be the next to advance science, and maybe us—right into oblivion!”, ”There it is: the red planet Mars, for over 2 000 years the symbol for war. And we fly in the face of providence and try to bring it closer to us!”, ”All women are afraid – it has become our natural state”, and simply ”Death”. There are many more, but you get the gist.

Making contact, Chris finds out that the Martians have created a utopia: the average life span is 300 years, illness and poverty have been eradicated, ”cosmic energy” has replaced the need for oil and coal, super-wheat has minimised the need for growing crops, thousands of years of peace have eliminated the war industry, and so forth. These wonderful advancements have terrible consequences on Earth where stocks crash, workers strike and the whole economy of the capitalist world collapses, while the Cronyn family is blamed for the woes of the world.

Parallel with this story is the story of Franz Calder (Herbert Berghof), the Nazi scientist who invented the ”hydrogen valve” that the Cronyns have been using. Calder lives in a shack in the Andes and reluctantly works for the Soviet Union, also trying to establish contact with Mars. The drunken, obnoxious Calder tells the Soviets, explicitly Arjenian (Marvin Miller) that he hasn’t been able to do so, but can listen in to the conversations between the Americans and Mars. In Kreml the commissar (Ben Astar) and general Borodin (John Topa) are delighted to hear of the crumbling of the Western economies and foresee a global communist takeover.

However, things take an unexpected turn when the Martians start scalding the humans for forgetting ”the message to love goodness and hate evil” that was sent to Earth by their ”supreme leader” 2 000 years ago. The Martians then start to quote the King James Bible, and the Americans listen in awe – could it be that the supreme leader of Mars is actually Jesus? Or even God? All is forgiven the Cronyns, and the world unites under the cross of Jesus Christ. News of this reaches the Soviet Union, and the people overthrow the ruthless communist masters and a Patriarch is set up as the new leader of Russia. God strikes down Calder’s hut with an avalanche. All the world unites under the word of God, the angels sing in the heavens and the choirs on Earth. All evil disappears from the face of the planet – all because humans are once again reminded of the message of the Bible.

But then there is a plot twist: Calder escapes the avalanche and turns up at the lab of the Cronyns – informing them that they have never spoken to Mars, but with Calder, who sent them all the messages that destroyed Western economy. But, the twist is that the messages from ”God” were received after his shack and transmitter had been destroyed – proving that the last messages were indeed from Mars and not from him. However, this is of no consequence, as he can prove all the initial messages were made from him, which will discredit all the ”God”-messages in the eyes of the world. ”Lucifer’s my hero. God beat him, but I’ll have beaten God!” he exclaims as the Cronyns discover he is something much worse than a commu-nazi: a Satanist! Oh how ever will this end?!

The screenwriters of this mess of a film are John L. Balderston and Anthony Veiller (who also produced), strangely enough. Veiller was twice Oscar nominated, won a Screen Writers Award and an Edgar Allan Poe Award, and worked on films like Stage Door (1937), The Killers (1946), Moulin Rouge (1952) and The Night of the Iguana (1964). Balderston wrote the play that the original Dracula (1931) film was based on, and did work on Frankenstein (1931, review), The Mummy (1932), Bride of Frankenstein (1935, review), The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935, Oscar nomination), The Last of the Mohicans (1936) and Gaslight (1944, Oscar nomination).

Balderston has gotten a lot of flack for this film, but one does wonder how much of the script was actually his. The film is based on the play Red Planet, performed first in 1932, and written by Balderston and John Hoare. The curious thing is that the religious fervour that the film tries to whip up is actually the butt of the joke in the play. The play starts off with a message from Mars, which is actually an excerpt from the Sermon on the Mount. The book The Red Atlantis: Communist Culture in the Absence of Communism describes that the tumult is caused by this message: the streets of London (where the play is set) is overrun by hymn singers, a Jewish financier tries to option the Bible and turns all the movie theatres in London into churches and an opportunistic politician makes himself world dictator under the banner of Christ. In the play, the twist of the story is that it was in fact a radio shack operator in the Alps who sent all the religious messages in order to cause pandemonium. According to the book American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1930-1969, in the play Linda Cronyn blows up the lab in order to protect the new religious world order – based on a lie.

The play was not especially popular, neither with critics or the audience when it was first shown at the Cort Theatre on Broadway. As with everything that had to do with space at the time, the only reference most theatre critics had was Jules Verne, and thus all reviewers seem to have called it ”a Jules Verne fantasy”, which is a rather daft notion. However, most were disappointed in the cop-out ending of the play and thought the themes were not followed up properly. New York Times wrote: ”It drifts off into a muddle of scrappy notions, and it tosses the whole story away by proving a hoax at the end”. The Cincinnati Enquirer wrote: ”Unfortunately the authors lose the thread of their essay and finish with a disappointing ending”. The play was cancelled after only seven shows.

Just because a film is a propaganda vehicle doesn’t mean it has to be bad, as proven by Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Michael Curtiz’ Casablanca (1942). Even as an atheist I can thoroughly enjoy films with religious themes, The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review) handled it well, and even the preachy Five (1951, review) had enough cinematic qualities for me to forgive the Bible-thumping script. The story of Jesus is one of the most amazing stories ever written, if you take it as simple fiction, and serves as a base for some of the best science fiction films ever made, such as the Star Wars epic or The Matrix (1999). But badly written propaganda is the worst plague of cinema, because a producer or a financer are often willing to excuse all manner of problems with a script, as long as it adheres to his or her political or moral sympathies. When it is more important to make a point than to make a good film, any project is doomed. Such is the case with Red Planet Mars.

1952 was a key year for bad propaganda, as it also introduced Invasion U.S.A (review). It was the height of the McCarthy investigations into Hollywood, the war between the United States and Korea was raging, and it was a presidential election year in America, with the Republicans backing former military man and deeply religious Dwight Eisenhower. Just as Christianity is today used as a counterpoint for jihadism, the American propaganda machinery propped up religion (especially Christianity) as the cure for ”atheist” Soviet communism. The fear of a third world war and nuclear annihilation also created a breeding ground for many religious films, such as The Next Voice You Hear (1950), from which Red Planet Mars seems to have taken a lot of cues.

But even contemporary critics were baffled by the film’s ”hokum”, as Variety put it, and A.W. of the New York Times wrote: ”this excursion into the terrifying blue yonder /…/ switches from its pseudoscientific exploration with such suddenness as to give even the most dedicated pulp fiction adventurer the megrims. In the midst of this tall tale the producers have seen fit to introduce a plea for a return to religion. It is a device that, in this case, is neither original nor convincing and serves only to make for loads of uninspired palaver about the comparative values of research and faith.”

More recently, Dennis Schwartz has called it ”One of the most obnoxious sci-fi films ever”. Richard Scheib of Moria, who gives Red Planet Mars a are 0/5 star rating, writes: ”The naivete of the film’s politics is incredible – it is not just the denouncement of the Soviet Union as evil but John Balderston’s tying up of religion in the mix as well. /…/ This is reflected in the film here where the Soviet Union is directly seen as a hotbed of atheism and religious suppression and by contrast the US is endorsed as an idyllic model of family, home and church-going Christians. /…/ the terms that the film tells it in, halfway between ludicrous 19th Century hellfire oratory and sentimental images of heart and God-fearing home, are utterly saccharine.” Reid at Films in Boxes awards the movie 1/5 stars: “it’s certainly science-fiction, because nothing in this movie is believable in the frame of the real world at all.” TimeOut sums it up as ”A candidate for the nuttiest sci-fi pic of all time”.

To be fair, not all think Red Planet Mars is completely hopeless. Bruce Eder at AllMovie, which rates it at 1.5/5 stars, concedes that it is an awful film in many ways, but: “it can be appreciated as an Edward D. Wood, Jr.-type unintended laugh-fest, which is the way in which it has usually been presented since the 1950’s and early 1960’s. But it can also be seen as a slightly nutsy-but-valid expression of the concerns of its era, as the politics of Armageddon flowed through the corners of middle America.” Damien Taymans at French Cinemafantastique, which gives the film 2/5 stars, has the same notion: “Underrated mainly for its proselytizing, Red Planet Mars remains one of the most entertaining (and disturbing) illustrations of the noxious paranoia that befell the entire Cold War era.” And I must admit to being somewhat baffled by this, but there are those who think that Red Planet Mars is actually a good movie. Pseudonym Nightowl at Classic Sci-Fi Movies thinks “the plot premise is pretty deep for a B-movie” and that “the script is well paced, and the plot twists work well”. Another anonymous reviewer at The Telltale Mind (probably the kindest critic on the internet, BTW) is sold, giving Red Planet Mars 3/5 stars. He/she writes: “those involved tried to do something a little different and to their credit, they did a good job. It may not be the best science-fiction movie ever made, but it gets extra points for being creative and keeping its audience watching.”

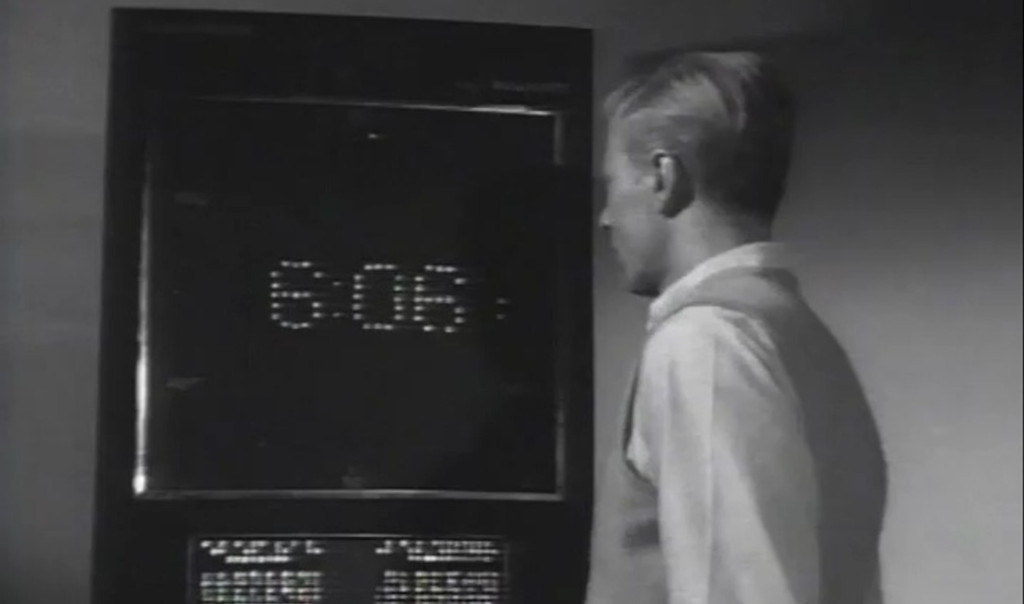

The film isn’t without redeeming qualities, I’ll admit that. Despite its low-budget feel, it is fairly well made. Despite being shot almost entirely in rooms of different kinds, it doesn’t feel like the cramped chamber dramas of some low-budget sci-fis. The home of the Cronyns is so well decorated that one wonders if it wasn’t shot in an actual home. The sets are well made, as is the lab gadgetry, including a huge oscilloscope screen or some such thing, that were making their entrance into sci-fi films in the early fifties.

The good design should come as no surprise, though, as the film was directed by Oscar-winning production designer Harry Horner, born in Austria-Hungary.

The acting is wooden across the board, if not laughably amateurish at times, especially when dealing with the Russians it’s almost like looking at a troupe of hobby stage actors. This could have been excused if it would have been the Russian-speaking actors who were bad, but when it is the English-speakers, it is inexcusable. Yes – the Russians actually speak Russian in the film. Ben Astar as the Soviet commisar, born in current-day Israel to Russian heritage, was fluent in Russian and made a career out of playing Soviet crooks. Russian-born bit-part player Leo Mostoyov turns up as a Soviet radio announcer and Joe Ploski, born in the States to Eastern European parents, and a number of uncredited actors in bit-parts keep up the Russian language. However, for understandability’s sake the script makes up idiotic reasons as to why the Russians speak English anytime something important is said. Lead actor Peter Graves is unusually stiff, although he does carry the film on his shoulders, at least giving a glimmer of class to the proceedings. Andrea King (real name Georgette André Barry) was also a respected and seasoned performer who had appeared on Broadway for nearly fifteen years, and ten years in film. Not that one would suspect that when seeing her shout her impossibly daft doomsday lines in Red Planet Mars. She really can’t be blamed for the performance, as she does the best with the stuff she is given. Few actors could have made anything coherent out of this role. The best performance of the film is given by Herbert Berghof as the embittered, alcoholic Nazi Franz Calder.

Of course it’s daft to nit-pick science in a film where Jesus lives on Mars, but I do find that films with impossible premises are often helped in their credibility of the rest if the science and the facts of the movie hold up – placing fantastical events against a backdrop of solid research can help sell crazy ideas. But if the rest of the film’s science and facts are badly prepared, one has a hard time to buy into the central premise of the movie, especially if the film is trying to make some sort of statement about contemporary life, such as this one. Unfortunately the science of the movie is bonkers and many simple facts are wrong.

The movie builds a central premise on the idea of ”canals” on Mars. Astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli first reported these “canals” in 1877, after observing a network of straight lines on the red planet. That they were interpreted as canals probably had much to do with the fact that at this time the Suez canal had just been completed and the first attempt of building the Panama canal had been undertaken. In fact, Schiaparelli called the lines he observed “canali”, which translates as “channels” and not “canals”, as they they were mistranslated in English. The person who most attributed to the idea that these observed lines were irrigation canals was American astronomer Percival Lovell. The idea was heavily contested even at the time, and by 1920 it was well and truly busted as an optical illusion due to low-quality telescopes that aligned dots into lines.

Other, more Earthly scientific and factual mistakes of the film are, for example, that the film gets the definition of Pi wrong. And although most scientists agree that mathematics and especially geometry is the key to establishing contact between civilisations, using Pi would necessitate that the Martians would use a 10-decimal system, which is completely artificial, and based in the metric system, which isn’t even used by all nations on Earth. Time measurements use a system of 12 or 60, and so forth. And even if the Martians had an equivalent of Pi, they would not need it to draw a circle, as the film states. Craftsmen through the ages have made circles with a piece of string and a pencil.

And even if the Martians by chance would use the same decimal system as we do, I have always had a hard time understanding how this shared understanding of 1,2,3 would then suddenly transform into complete understanding of each other’s languages in a matter of hours or minutes, as is so often the case in sci-fi films. I have been able to to count to 1,2,3 in Spanish since I was five, but that hasn’t led to any greater understanding of the language. I still can’t say ”We have created a super-wheat using radiation harnessed from cosmic radiation, that can feed a million people from a single acre of farmland” just because I understand uno, dos, tres.

Furthermore – Einstein didn’t split the atom as Linda at one point claims, and nations seldom collapse completely just because they are aware that other nations are more effective than others, as in this movie. Why exactly all goes to hell when Mars informs Earth that they have advanced technology is a bit hazy. That’s not the way the market works. At one point the president quotes a line from a poet: ”Solution there is none, save in the Golden Rule of Christ alone”, and claims it is Ralph Waldo Emerson. In fact it is anti-slavery poet and activist John Greenleaf Whittier, but he probably wasn’t in good standing with the conservative forces behind the film. And so on and so forth.

Would this film have been made tongue-in-cheek it might have fared far better. But when you make a film that says Jesus is a little green man on Mars and try to build it up as a solemn philosophical and political fable you are asking for ridicule. However, the film is fairly well made and the actors are not to blame for its deeply flawed script. The talent involved is the one reason the film doesn’t fall into the black pit of zero stars, but it is dancing close to the edge.

Director Harry Horner won Oscars for his design in The Heiress (1949) and The Hustler (1961). Red Planet Mars was his first directorial effort, and considering that, it is not badly directed, if not well either. There is a static feel to the movie, although the shots are well composited. That, however, would probably be thanks to cinematographer Joseph F. Biroc, who had previously worked on Frank Capra’s 1946 Christmas classic It’s A Wonderful Life. He had a prolific career, but got something of a second coming in the seventies and later with Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971), Superman (1973) and The Towering Inferno (1974), where he photographed the action sequences and was awarded an Oscar for the effort. Biroc also became known as the cinematographer to go to for comedies, as he shot blockbusters like Blazing Saddles (1974), Airplane! (1980), and Airplane II: The Sequel (1982). He photographed a number of episodes of Adventures of Superman (1952-1958), as well as the sci-fi films Donovan’s Brain (1953, review), The Twonky (1953, review), Riders to the Stars (1954, review), The Unknown Terror (1957, review), and The Amazing Colossal Man (1957).

By the time he made Red Planet Mars lead actor Peter Graves had already done the role that became his breakthrough, as the ”security officer” amongst a group of American POW’s in Billy Wilder’s hit film Stalag 17, which wasn’t released until 1953. In 1971 he won a Golden Globe for his recurring role as James Phelps in the original Mission: Impossible TV series (1967-1973), a role which he reprised in the remake (1988-1990). He also played Captain Oveur in Airplane! alongside Victor, Clarence and Roger.

Graves never made it to the top of the bunch as A-list film actor, but carved out a career as a B movie leading man in the fifties, including in Z-grade sci-fi films such as Killers from Space (1954, review), It Conquered the World (1956, review) and Beginning of the End (1957). He had the leading role in The Clonus Horror (1979) and had a cameo as himself in Men in Black II (2002). However, it was in TV that he made his name, where he starred in a number of successful TV series, and became a bona fide star thanks to his starring role in the TV series Mission: Impossible. He also appeared in a few TV films, including the abysmal sci-fi turkey The Eye Creatures (1965) where he did an uncredited voice-over, and the interactive movie/computer game Darkstar: The Interactive Movie (2010), where he acted as narrator. He died the same year as the game was released. Graves was actually called Peter Duesler Aurness and was of partly German and partly Norwegian ancestry. His family’s original last name was the Norwegian Aursness, which was Americanised to Aurness. However, Peter chose to use a maternal family name, Graves, to not be confused with his brother James Arness of Gunsmoke fame. Sci-fi fans may know James Arness as the Thing in The Thing from Another World (1951, review).

Austrian-born Herbert Berghof had been a stage actor under legendary Max Reinhardt in Germany and started teaching acting upon his arrival in New York in 1939. In 1944 he opened his own acting school, and had a successful career on Broadway both as actor and director through most of his life. He is perhaps best remembered for his direction of Waiting for Godot, starring Earle Hyman and Mantan Moreland in 1957. He acted in little over 30 films and TV series, and is perhaps best known as Rivetowski in Harry and Tonto (1974) or as Dr. Huber in Times Square (1980). He was married to stage legend and acting teacher Uta Hagen. Berghof trained actors like Jon Stewart, Al Pacino, Robert de Niro and Anne Bancroft, and was called one the the nation’s most respected acting coaches by the New York Times.

Walter Sande who plays Admiral Carey was a staple character and bit-part player, who also turned up in a rather substantial part as the police desk clerk in Invaders from Mars (1953), and a smaller part as a sheriff in The War of the Worlds (1953, review). He also had a bit-part in The Man They Could Not Hang (1935, review) and appeared in a few sci-fi series. He had a long and prolific career, and is probably best remembered as Captain Bullwinkle in the TV series The Adventures of Tugboat Annie (1957).

Marvin Miller as Arjenian was primarily a voice actor who was something of a phenomenon in Chicago and would go on to win Grammies for his recordings of Dr. Seuss. Miller also does what he can with the insipid role, which requires over-acting and chewing scenery as to not make the lines sound all too daft. His voice can be heard in the animated films of Gerald McBoing-Boing of the fifties, The animated Pink Panther TV series, The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo (1964-1965), and he was the narrator for the TV series The F.B.I. (1966-1974) as well as the cult series Police Squad (1982), which gave birth to the Naked Gun films.

Miller had a recurring role as Captain Quick in he live-broadcast TV series Space Patrol (1950-1955) and narrated the lowly King Dinosaur in 1955 as well as the English version of Godzilla Raids Again (US release: 1959). In 1956 he did what he is perhaps best loved for by sci-fi fans: provided the voice for Robby the Robot in Forbidden Planet (1956, review). He reprised the role in The Invisible Boy (1957), the TV series Wonder Woman (1979) and Gremlins (1984). He narrated The Deadly Mantis (1957, review), The Phantom Planet (1961), and the TV series Electra Woman and Dyna Girl (1976). He appeared in, dubbed or provided voice work to The Story of Mankind (1957), The Last War (1961 Japan, 1967 USA), Godzilla vs. Monster Zero/Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965 Japan, 1970 USA), Submersion of Japan (1973 Japan, 1975 USA), Fantastic Planet (1973), Empire of the Ants (1977) and the TV series Land of the Lost (1975). And as a Finn, I can’t refrain from mentioning that Miller also narrated the English version of the Finnish-Soviet co-production Sampo (1959) or The Day the Earth Froze (1964, USA), based on the folk tales of Kalevala.

Willis Bouchey, who plays he president, was a character and bit-part actor, mostly in westerns, but also appeared in Them! (1954, review) and Panic in Year Zero! (1962). And to the delight of sci-fi geeks all over the world, the US secretary of defence is played by science fiction supporting actor extraordinaire, Morris Ankrum. Ankrum had previously appeared in Rocketship X-M (1950, review) and Flight to Mars (1951, review), and would go on to play in over a dozen science fiction films in the fifties and sixties. For more on him, see the afore mentioned reviews. And while we are on the topic of recurring bit-part actors, do keep a lookout for Franklyn Farnum – always there, always uncredited. Although the year was only 1952, this was Farnum’s fifth fifties sci-fi film. Another extra worthy of mention is Tom Keene, a former B-western leading man, now uncredited. For sci-fi fans he is a person of interest for playing one of the major roles as Colonel Edwards in Ed Wood’s legendary Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957, review). Another western B-star who found himself in uncredited bit-parts in sci-fi in the fifties was Robert Stevenson, who also appeared in The Day the Earth Stood Still, Abbott and Costello Go to Mars (1953) and Kronos (1957, review). Wade Crosby appeared in Invasion U.S.A. and Westworld (1973).

Editor Francis D. Lyon is interesting inasmuch as this was the last film he edited before he transitioned to the director’s chair, and directed such B classics as The Cult of the Cobra (1955) and The Great Locomotive Race (1956). He had previously edited H.G. Wells’ Things to Come (1936, review), and continued on to direct Destination Inner Space (1966), Castle of Evil (1966) and The Destructors (1968).

Art director Charles D. Hall was a true veteran, who had worked on everything from Frankenstein, The Invisible Man (1933, review) and Bride of Frankenstein to turkeys like The Flying Saucer (1950, review). Apparently seeing as though the films he was getting offered weren’t getting any better, Hall did only one more film after this, then ended his career in TV before he quietly retired in 1955. The twice Oscar-nominated legend died 81 years old in 1970.

Sound engineer Victor B. Appel also worked on cult classics like Space Master X-7 (1958), Angry Red Planet (1959), Hand of Death (1962), Varan the Unbelievable (1962) Cyborg 2087 (1966) and Dimension 5 (1966).

Janne Wass

Red Planet Mars. 1952, USA. Directed by Harry Horner. Written by John L. Balderston & Anthony Veiller. Based on the play Red Planet by John L. Balderston and John Hoare. Starring: Peter Graves, Andrea King, Herbert Berghof, Walter Sande, Marvin Miller, Willis Bouchey, Morris Ankrum, Orley Lindgren, Bayard Veiller, Ben Astar, Wade Crosby, Franklyn Farnum, Tom Keene, Leo Mostovoy, Joe Ploski, Robert Stevenson. Music: Mahlon Merrick. Cinematography: Joseph F. Biroc. Editing: Francis D. Lyon. Casting: Maurice Golden. Art direction: Charles D. Hall. Set decoration: Murray Waite. Makeup supervisor: Don L. Cash. Production management: Joseph Paul. Props: Clem Widrig. Sound engineer: Victor B. Appel. Produced by Donald Hyde and Anthony Veiller for Melaby Pictures Corp & United Artists.

Leave a comment