Strange deaths occur at an underground US research facility controlled by a computer. Suspicion falls on two helper robots, Gog and Magog. This 1954 Ivan Tors thriller in colour has a great setup, but feels more like a science lesson than an SF film. 5/10

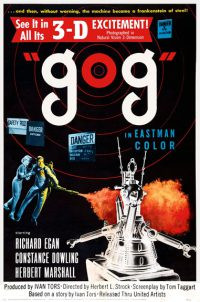

Gog. 1954, USA. Directed & edited by Herbert L. Strock. Written by Ivan Tors, Tom Taggart, Richard G. Taylor. Starring: Richard Egan, Herbert Marshall, Constance Dowling, John Wengraf, Philip Van Zandt, Michael Fox, William Schallert, Billy Curtis. Produced by Ivan Tors. IMDb: 5.5/10. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

If science fiction enthusiasts bemoan the exclusion of visionary producer George Pal from discussions about pioneers of the film genre, then they should be doubly as wronged over the fate of the now almost forgotten Ivan Tors. If Tors is remembered today, it is mainly as creator of the Flipper franchise and other family-friendly animal shows. But in his own way, Ivan Tors was just as visionary a science fiction producer as Pal in the fifties, albeit working with significantly lower budgets. His main claim to fame within sci-fi is his movie trilogy about the fictional OSI, or Office of Scientific Investigation, a sort of precursor to the X-Files, without the new-age mumbo-jumbo and lacking in aliens. Gog was the final film in the OSI series, and probably the most ambitious one.

The film unfolds in an underground research laboratory in the Nevada desert, where scientists are working on experiments aimed at winning the space race for the USA. When two scientist working on experimental cryonics (Michael Fox and Marian Richman) are mysteriously frozen to death in their own laboratory, lead scientist Dr. Van Ness (veteran star Herbert Marshall) calls in beefcake detective Dr. David Sheppard (Richard Egan) from the Office of Scientific Investigation. Sheppard is shown around the underground station by Dr. Joanna Merritt (Ivan Tors’ future wife Constance Dowling), who just so happens to be a colleague of Sheppard’s, now working as an undercover agent for the OSI at the lab. And as things tend to go in the movies, the pair are also love birds. Most of the film’s running time is taken up by this tour of the facility, which is divided into sections of danger and security based on how far below ground each level is – furthest down we, naturally, find the nuclear reactors. There’s also a test facility for zero gravity, where a male and a female test subject perform acrobatic feats, a G-force testing facility, a radiation lab and a lab where the shifty Dr. Pierre Elzevir (Philip Van Zandt) and his assistant/wife (Valerie Vernon) have designed a heat ray with the help of a solar mirror, capable of melting metal and destroying cities. Furthermore, there is a radio room picking up signals from around the globe and even outer space, through a bizarre machine utilising – of all things – tuning forks. At each stop we get a high-school lecture in basic science, such as how the sun works or what sound waves are, plus a demonstration.

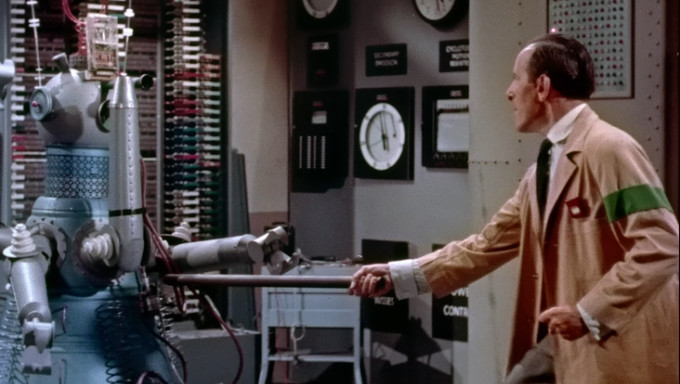

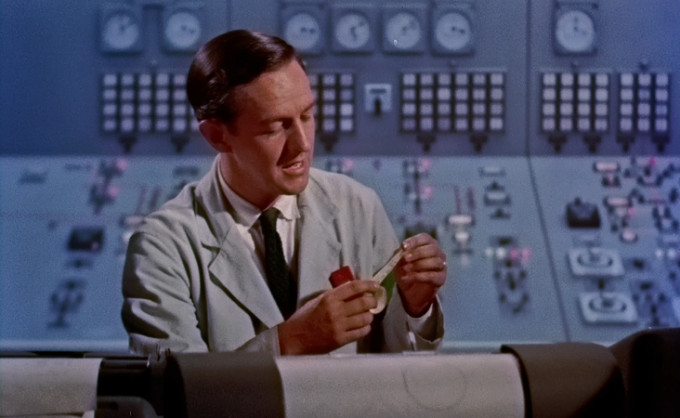

But most importantly, there is the computer room, bossed over by the arrogant Dr. Zeitman (John Wengraf), with the help of assistant Engle (William Schallert). The real marvel of the science station is the Nuclear Operative Variable Automatic Computer – NOVAC – automatically controlling the whole facility. NOVAC is aided in its task by two robots by the ominous names of Gog and Magog. Neither the computers nor the robots are sentient, though, but take commands from the scientists through punched paper strips. These marvellous machines were designed and built – it is pointed out – in the neutral country of Switzerland, which is important for the jingoistic morals of the film, if nothing else. Through his tour, our OSI agent Sheppard is informed of the fact that the main goal of all the research is to build an American space station equipped with surveillance and spy gadgets, as well as the solar death ray, so as to keep the US safe from ”the enemy”.

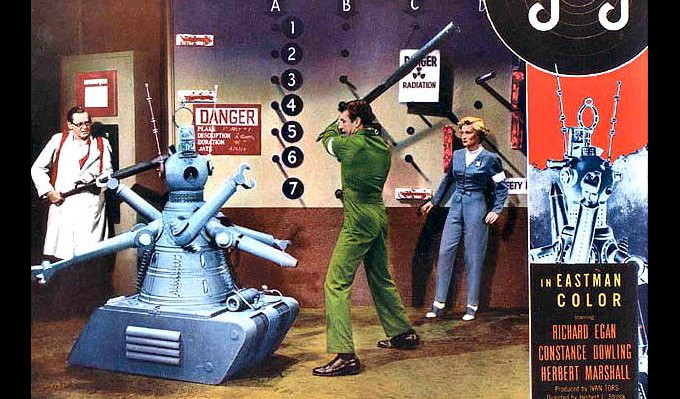

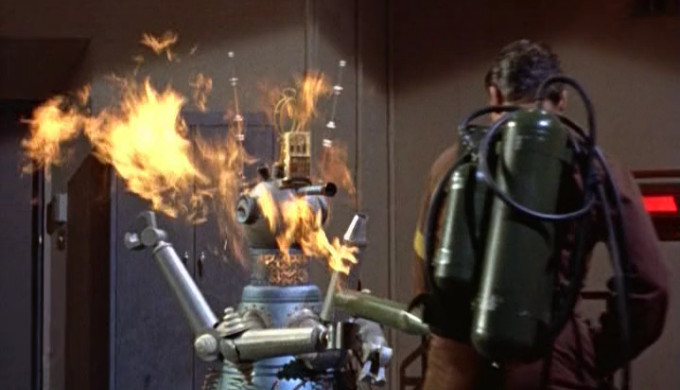

Things continue to go from bad to worse. More mysterious deaths occur. A piece of unprotected radioactive material ends up in the radiation lab, killing a scientist, and Sheppard keeps finding strange transmitters throughout the electronics of the station. Of course Gog and Magog take up arms against their human masters, and it all turns into a big whodunnit mystery as Sheppard tries to find out who is sabotaging the station – it takes him a bit too long for credulity to realise that it is NOVAC who’s running amok. The question is whether it is thinking for itself, or if somebody is controlling it; could it be the haughty Dr. Zeitman or his assistant Engel? Maybe the shifty Dr. Elzevir isn’t just interested in watching female pilots performing zero-G acrobatics in body stockings, but has even more ominous plans? Was it Colonel Mustard in the library with dagger? Or – maybe it isn’t even anyone in the building? If NOVAC can radio-control things outside the base – perhaps someone could control NOVAC from the outside? Perhaps – ”the enemy”? It all boils down to a dramatic toe-to-toe between our good agent and the mechanical monsters Gog and Magog, as the robots try to sabotage the ”nucular reactor” in order to make big boom. Will America prevail?

Often overlooked when speaking of influential science fiction films, this is a first in many respects. First of all, we have the secret underground laboratory, with its different security-graded levels. Secret underground lairs and labs have been a mainstay of sci-fi at least since Captain Nemo took the readers to his submarine dock hidden inside a volcano in Jules Verne’s 1870 novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

The layout and the security protocols in the science station in Gog were completely new to sci-fi films. Nothing of the sort exists in any previous movie. These kind of facilities became staples in film and TV in the seventies, and the man who often gets credit for this is author and occasional director Michael Crichton, one of the giants of modern sci-fi writing. It was his Wildfire laboratory in the 1969 novel The Andromeda Strain – filmed by Robert Wise in 1971 – that became the model for secret labs found in everything from James Bond movies to the Resident Evil saga (1996-) and more recently the HBO adaptation of Westworld. To my knowledge Crichton never publicly named Gog as an inspiration for the novel, but there’s no doubt that he watched the film as a kid. The Wildfire research station and even large chunks of the plot in the novel are directly – blatantly – lifted from Gog.

Another first in the film is the computer NOVAC. It’s certainly not the first computer on film, nor the first mechanical contraption to go haywire – but it is the first film that deals with the risks involving an all-encompassing computer network, whether it becomes sentient, like in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Terminator (1984), or is taken over by humans for nefarious reasons, like in Billion Dollar Brain (1967) or Live Free or Die Hard (2007). It does have a precursor of sorts in the German film Master of the World (1934, review), or Der Herr der Welt. Directed by the forgotten silent movie action star Harry Piel, the film tells the story of a mad scientist creating an army of robots controlled by what is essentially a central computer – decades before anyone knew what a central computer was.

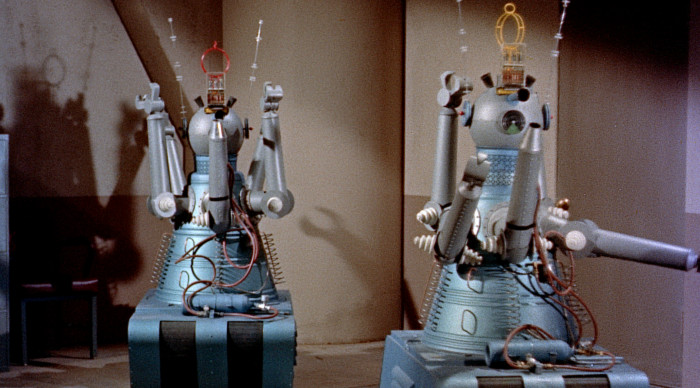

And let’s not forget the title characters, Gog and Magog. This is probably the first time in a film that robots are portrayed in any scientific and realistic manner. There had been no lack of robots in earlier movies, but almost all of them either had been portrayed as humanoid duplicates (as in Metropolis, 1927, review or The Perfect Woman, 1949, review) or were made out of cardboard boxes and drain pipes. But Gog and Magog, although adorably silly-looking to modern eyes, are actually more or less designed on the same principle as security and bomb disposal robots are today. Instead of walking on two feet, they run on treads, and have five arms each instead of two, each with different attachments. Like modern robots they can perform rather simple tasks like open doors, patrol, retrieve objects from dangerous areas and so forth. Like modern robots they have sensors that can recognise human presence, and are programmed to respond to different stimuli. Unlike modern robots, the wiggle their arms like toddlers when they move. The design of Gog and Magog bears some resemblance to the legendary Daleks of the long-running British Doctor Who series, created a decade later. Oh, and why anyone would name their helper robots after Gog and Magog, the minions of Satan at Armageddon, well, that’s up for grabs. Maybe the inventor was into black metal.

Producer Ivan Tors was fascinated by computers, they played small but crucial roles in his two previous OSI movies The Magnetic Monster (1953, review) and Riders to the Stars (1953, review). Another thing he liked was G-force testing, as he filmed actual test rigs in both Riders to the Stars and Gog. In the former, he filmed the lead actor riding the centrifuge, but in Gog he substituted the actors with dummies mid-scene, as the actors couldn’t take the speed which director Herbert Strock wanted use for it in the movie (probably just as well, as the speed kills the characters in the film).

Another detail is that this is the first time in a feature film that cryonic sleep is considered as a solution to long and arduous space journeys. While never actually used on humans in the film, we do get an opening scene of the scientists freezing and reviving a monkey. Cryonic sleep had been utilised in a number of books in the 19th and early 20th century, mainly as a plot device to let protagonists travel forward in time – mostly through being accidentally encapsulated in ice, and as such Harry Houdini made use of the trope in the film The Man from Beyond (1922, review) – incidentally Houdini was also involved in the film serial with the first appearance of a robot, The Master Mystery (1919, review). In the 1940 film The Man With Nine Lives (review), Boris Karloff plays a physician who experiments with ”frozen therapy” before accidentally burying his patients and himself in ice, only to be revived seven years later.

One of the first literary stories of deliberate medical cryonic treatment was the short story Cool Air by H.P. Lovecraft, about a clinically dead man keeping himself ”un-dead” through low temperatures. It was published in Tales of Magic and Mystery in 1929. The first well-known literary source utilising cryonic stasis for space travel was Neil R. Jones’ short story The Jameson Satellite, published in Amazing Stories in 1931, in which a professor wants his body to be preserved after death in the chill of space for all eternity, orbiting the Earth in a satellite – until 40 million years later, when he is picked up and revived by cyborgs from another planet. One of the first stories where actual living astronauts froze themselves for a long space voyage was A.E. van Vogt’s Far Centaurus (Astounding Stories, 1944). Today, even NASA is doing research on cryonics, hoping to replicate the torpor of hibernating mammals like bears and rodents.

There’s no doubt, thus, that Gog would have had a huge influence on later sci-fi. Unfortunately it suffers from the same problems as the entire OSI trilogy: the scripts don’t quite live up to Tors’ underlying ideas. And even if the scripts would have been better, his independent productions lacked the budgets that someone like George Pal had access to. Another problem was that Tors competed in a genre primarily catering to juvenile audiences who wanted to see monsters and UFOs. Instead Tors wanted his films to be educational, and they are all laden with overbearing scientific lectures that stall the movies and inspire wooden performances from even the best actors.

The talky first half of the Gog is counterbalanced by a fast-paced second half, largely thanks to editor-turned director Herbert L. Strock, who co-directed both The Magnetic Monster and Riders to the Stars. I have written more about him in my reviews of those films, so head over there for more information. The film was shot in beautiful Eastman colour and in 3D. Ironically Strock was almost blind on one eye, so he had to rely on cinematographer Lothrop B. Worth to ensure that the 3D images looked good. Incidentally André de Toth who directed House of Wax in 1953 – one of the most influential 3D films of the fifties – was also blind on one eye, in fact he only had one eye. Gog has been remastered for Blu-Ray in glorious colour and 3D as recently as 2016, so I highly recommend getting your hands on a copy.

When we’re talking about ”low-budget” it’s always good to be specific. People like Roger Corman and W. Lee Wilder made films on shoestring budgets like 30 000 dollars in the early fifties, while films like Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review) had makeup budgets larger than that, but are still considered low-to-mid-budget movies. Gog falls somewhere in between, with an estimated budget of 250 000 dollars. In today’s money, that would fall somewhere between 2 or 3 million dollars, depending on how you count. Not a lot for a Hollywood movie, but you can make a pretty decent independent film for that dough.

Director Strock and art director William Ferrari do what they can with the scant budget, but they can’t help that the walls look like painted plywood. Designing the more futuristic look of the research station, they have opted for materials that were new, but readily available at the nearest home & garden shop: green, corrugated fibreglass panels and glass bricks. Mostly the characters move around in non-descript, narrow corridors or equally non-descript rooms filled with cabinets adorned with buttons, lights, gauges and levers. The best-looking lab is probably the freezing lab, which also has one of the coolest-looking scenes (pun intended). The filmmakers have even added a bit of surprising realism by installing a windscreen wiper on the window between the freezing chamber and the control room, foreseeing the build-up of condensation. The scene is a great and riveting opening. Michael Fox plays the scientist trapped inside the freezing chamber with terror-stricken panic, hammering on the glass and frantically pulling on door handles and levers.

In Tom Weaver’s book It Came from Horrorwood Fox explains how the effect of the frost building up on his face, hair and clothes was achieved by makeup artist Ted Larsen: ”[he would] take powdered alum, dissolve it in acetone, and then spray me with it; and as the acetone evaporates very quickly, the alum turns out white.” For the final frozen-solid look, they sprayed Fox with liquid wax.

The gadgetry cabinets were partly re-used from the previous two OSI films – you can definitely spot the green mechanical cabinets from Riders to the Stars. Gog was filmed in 15 days at Hal Roach Studios, and re-acquaints us with several props and costumes used to film other low-budget movies at the same premises. The sound lab with the tuning forks uses the instrument panel from the Project Moon Base (1953, review) rocket. The filmmakers even left in the 16 mm film reel that the makers of Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review) glued onto the wall when they re-used it previously. And this is now at least the fifth 1950s science fiction films in which the iconic space suits turn up. They were first made for George Pal’s Destination Moon (1951, review), and then re-used in Flight to Mars (1951, review). They were re-used again in Project Moonbase, and handed down to Cat-Women of the Moon. In Gog they are now ”pressure suits” in the G-force test scene. Along the way the helmets changed, and the ones used here are the fish-bowl type with a strange funnel attached the face-plate used in Cat-Women of the Moon, that some believe are either hand-me-downs from the TV series Tom Corbett, Space Cadet, or simply just off-the-shelf toys. It is unclear whether the suits were the actual ones worn on-screen in Destination Moon, or if they were the ones used by marketing people handing out leaflets prior to the premiere in 1950. Another theory explaining the seeming abundance of these suits is that there would have been a company in Hollywood making and selling them fairly cheap.

The special effects are not bad for a film like this at all, even though there is nothing incredibly complicated in the movie. Wisely Tors stays away from using a lot of miniatures or rear-projection (with a few tastefully executed exceptions, such as the Hoover turbines showing up outside a window), and sticks to small explosions and fire, as well as the very well done cryonics scene. Holding the reins in the special effects department was veteran Harry Redmond Jr., Tors’ go-to guy, who had worked closely with Willis O’Brien on King Kong (1933, review).

On the whole, the acting is decent, considering the George Lucas-esque lines the poor actors have to utter. Best of the lot is handsome hunk Richard Egan, who stood on the cusp of stardom in 1954, having won a Golden Globe as most promising newcomer in 1953. He has a rugged Hollywood charm, although in this film at least with a slant of casual fifties sexism. He is very credible as a government agent and brings a sense of grounded realism to the proceedings of Gog, and is one of the few able to breathe life into the stilted dialogue, even if the frustration with the turgid lines sometimes shines through.

And the proceedings are sometimes quite incredible, as when the scientists demonstrate the heat ray by burning up a model city to show its power. Egan stares in amazement as if this was somehow proof that the contraption could level an entire city. No, good scientist, this was a proof that if you concentrate sunlight with a mirror you can ignite small blocks of wood, I did it with a magnifying glass when I was a kid. And what? Do the scientists build new model cities every time someone comes to visit just so they can burn them, or was this one special, waiting for a time when a government agent came by to investigate murders?

The tuning fork room is even more bizarre. First of all – they’re bloody tuning forks, not state-of-the-art audio equipment. Second, did the scientists build a machine for enhancing sound to a lethal level, and then forget to put a mute-button on it? Is there no off-switch? At one point the ”enemy” creates sound waves strong enough to light a chair on fire (don’t ask), but all the scientists in the room are perfectly fine as long as they cover their ears with their hands. Truly bizarre.

This is also a film that clearly shows how little was understood about nuclear radiation, even by people who were extremely knowledgeable about science, like Ivan Tors – and they even had a scientific consultant named Maxwell Smith working on the script (Smith blew off his arm in an accident when working with explosives in Riders to the Stars). The scientists casually stroll around a room with a big chunk of nuclear material exposed – one of them does have a haz-mat suit, but the others are only two paces behind – as if that made any difference. In the end of the movie the two love birds wake up in a hospital and Egan tells Dowling that they are just fine, they just got a bit too much radiation, like they had a bit too much to drink yesterday. However, this probably shouldn’t be held over the filmmakers, as researchers were just beginning to understand the long-term effects of radiation, and that sort of knowledge was strictly covered up by the US authorities, who were pushing for the advancement of nuclear power.

However, the film is one of the few early films that gets the computer right – all the way down to how robots would be working in the future. In a way the movie foreshadows the ”internet of things”. It also predicts how computers could be hacked remotely in the future, decades before the internet, as well as the stealth aircraft, even if it gets the science slightly wrong on both occasions (you don’t need line of sight to send radio waves, and stealth planes aren’t stealthy because of the materials of their hulls).

As mentioned, the robots Gog and Magog were pretty ground-breaking as far as their design went, and the way in which they were portrayed as functioning – very much foreboding robots of today, a slight stroke of genius by Ivan Tors. But like most robots of that era, and years to come, they were played by a human in a ”suit”, in this particular instance by two diminutive actors, who fit inside the central conical shape of the robots. They were able to move Gog and Magog, rotate the upper torso of the robots, as well as control the arms. Despite the unique design, however, the robots don’t quite look like the killing machines they are supposed to portray. They look a bit too flimsy and light, and especially the arms look exactly like what they are: lightweight plastic tubes with waldos for hands. It doesn’t help that Herb Strock instructed the actors inside the machines to constantly wiggle the arms up and down for no apparent reason, making them look like childish caricatures of robots, and giving away the flimsiness of the build. They might actually have come off as rather intimidating, had they just held those bloody arms still. But as Michael Heerema puts it at the blog Nights and Weekends: ”it’s a little disconcerting to see supposedly highly-trained security agents cowering in front of a giant piece of plastic with a large pair of pliers”. The robots were operated by the legendary tiny actor Billy Curtis.

Director Herbert Strock does a decent job with the direction, but it seems clear that he isn’t exactly an actor’s director, as the most part of the film has the actors standing and talking, and many of them deliver very wooden lines. But he is good with the visuals, and is aided by the fact that he also served as editor on the film. Strock was originally and primarily an editor, but as mentioned earlier, had co-directed both of Ivan Tors’ previous movies, first alongside writer Curt Siodmak, and then with actor Richard Carlson, both times uncredited.

In Return of the B Science Fiction and Horror Heroes, Strock tells Tom Weaver that Tors’ talky scripts were deadly, and he did what he could on Gog to work around it. Strock worked alongside screenwriters Tom Taggart and Richard G. Taylor to put more emphasis on the action and the visuals of the film. According to Strock, the second half of the movie was edited in a completely different way than originally intended, as he felt the movie was bogged down – and made the final half very fast-paced instead. As everyone ever asked about Herbert Marshall, Strock remembers him with great fondness. Marshall famously had his leg amputated early in his career, and did all his great work with a prosthetic right leg, even when he was hopping up and down staircases as a young leading man. As he got older, the leg started giving him great pain, eventually leading him to drink heavily. He had a noticeable limp, but developed a sort of shuffling walk to cover it up. At one point during filming he asked Strock if his limp was too obvious in a scene. Strock, who at the time didn’t know that Marshall had only one leg, said he thought it was a ”good gimmick”, which angered Marshall. Strock tells Weaver: ”I felt terrible, I apologized, and he, being the charming Englishman that he was, understood. I was terribly hurt when he passed away.” Strock continued directing B movies and TV shows, but the OSI films remain his crowning achievements as a director. Read more about Strock in my reviews of the two earlier movies.

Strock was perhaps too engaged with the lush Eastman colours and the 3D photography to take advantage of the possibilities for creating a claustrophobic suspense drama. Everything’s a bit too wide and bright for us to get the feeling of being trapped far below ground. This works against the film, as a more confined feeling would have created some much needed suspense – and the script completely fails to explore the psychological and social aspects of the confinement.

Despite the forward-looking perspective of Tors’ whole OSI trilogy, the films are invariably also quaint artefacts of the early cold war era. The Magnetic Monster told the story of the OSI agents trying to neutralise a radioactive material that kept on consuming all energy in its vicinity, and threatened to devour the whole planet. The idea was borrowed from Arch Oboler’s radio play The Chicken Heart, but it doesn’t take too much imagination to see the warning Tors was making about the disastrous potentials of nuclear power. With Riders to the Stars Tors then moved on to the space race, and here the reds were now lurking under the beds. The premise of the movie was a completely unscientific idea used as a plot device to send our scientists into space, but the underlying objective here was to build an American space station armed with surveillance equipment and nukes before ”the enemy” got there first. Gog was the culmination of previous films, combining both the nuclear theme and the space race – and upping the level of paranoid nationalism to eleven.

What’s surprising is that Gog introduces a level of unabashed jingoism that wasn’t present in the previous movies, that held the military and politics at arm’s length. Scientists were always the heroes of the films, and most of them were more interested in the science than in the application of it. But in Gog the fight against the Russkies is front and centre from the beginning, and the movie is oozing with paranoid fear of the communists. One does wonder if this was not something that Taggart and Taylor added to the script to heighten the tension, since it seems a bit un-Tors-like. Anyway, the gist of the movie is that no-one can be trusted, not even ”neutral countries” like Switzerland, that built the computer. The script-writers are trying to say that America stands alone, and in the end it is American science and technology that will prevail. The answer to all future problems is that USA should have a death ray orbiting the Earth, capable of wiping out entire countries in the blink of an eye.

This was the fifties, after women had taken their place in the workforce during WWII. Thus women in sci-fi had progressed from being secretaries to working as actual scientists. This doesn’t mean these fifties films were beacons of gender equality. No, invariably the really important scientists were always older men, and the female scientists were always young, slim and perky, and no matter how important their jobs, they always had time in the morning to create the perfect perm. And the chosen footwear for radiation labs was naturally high heels. And no matter how smart the female scientists were, when push came to shove, they always needed to be saved by a male hero – that’s after falling in love with the chauvinist prick. And thus is also the case in Gog.

It isn’t hard to imagine Michael Crichton becoming enthralled by this film as a 12-year old, and later thinking he could make the story better. Crichton threw out the direct communist references and with his own degree in medicine, it was natural to replace them with an alien virus. He streamlined the story, and added bits and pieces, but basically The Andromeda Strain is Gog on steroids. A new guy arrives at an underground science station to investigate strange deaths caused by an unseen killer. A threat from the outside (commies/aliens) takes over the inside of the science station, trapping its inhabitants. Our hero must fight to prevent the destruction of the station in a nuclear explosion, and in the long run the destruction of America/the world. In a way the theme resurfaces in other stories – isn’t Jurassic Park basically The Andromeda Strain with dinosaurs instead of a virus?

The film arrived at the very last gasp of the short-lived 3D craze, and didn’t get many 3D screenings, as many theatres opted to show it as 2D, which apparently angered Herbert Strock. The same fate awaited a few other 3D movies released in 1954 – Revenge of the Creature (review) was filmed in 3D, but released in 2D. For many years, no left-eye print of Gog was thought to have survived, until one pretty badly degraded copy turned up some 20 years ago, I believe. It has now been digitally restored into its former glory on Blu-ray and currently Amazon Prime.

Contemporary reviews were mixed and bemused. Bosley Crowther at The New York Times wrote: “This is not one for rational observation. The fantastic experiments are fun and the clatter of the ‘villians’ is amusing. But Gog is utter nonsense, on the whole.” Motion Picture Herald’s William R. Weaver said of Gog, “The production moves steadily forward, keeping interest growing at a steady pace, and exciting the imagination without overstraining credulity”. Left-wing The New Republic called it “pleasantly inventive”, but decried its “ideological moralizing”.

Today Gog has a 5.5/10 rating on IMDb based in over 1,100 reviews, making it one of the better-known low-budget SF movies of the fifties, but no Rotten Tomatoes consensus. In 2016 The Telegraph included the film’s titular menace in the 30 best robots in film, and in 2020 Screenrant named the movie among the “The 10 Most Ridiculous Movies About Evil Computers”. AllMovie gives it 2/5 stars, with Bruce Eder noting that it “sometimes seems almost more like a science lesson or a visit to a science exhibit than a science fiction film”. Eder continues: “So it lost some of the younger audience for the genre, but at the same time Gog appealed to older, more mature filmgoers”. TV Guide is mildly positive: “It’s a bit talky for its own good and the direction tends to slow things down for explanations, but overall it’s a good way to spend a Saturday afternoon.” Samm Deighan at Diabolique Magazine gives it an unusually positive review: “Gog will be a pleasant surprise for viewers tired of silly ‘50s sci-fi films, but will disappoint anyone hoping to find only goofy effects and campy dialogue.” Christopher Stewardson at OurCulture Mag delivers an interesting write-up: “1954’s Gog is interesting artefact of ’50s Americana. To watch it now is to look at a vision of the future from the past, answering science fiction’s most pertinent question: what if? […] Gog is a flawed but fascinating look at technological possibility. Part of its appeal now is in seeing a depiction of the futuristic that’s so evidently rooted in the past: robots instructed by paper slips; an underground electronic base with a paper filing system; a scientist stood in a technological supercomputer insisting that the human body will never go into space.” Stewardson gives the film 2.5/5 stars, concluding: “Despite its flaws, Gog is a very watchable film. Even though the ideas played with are tinged with overt Cold War anxieties (many of them reactionary in nature), the film’s vision of futuristic possibilities is still fascinating.”

Derek Winnert finds the film’s pros outweigh the cons, and gives it 3/5 stars, calling it a “rather jolly […] fantasy film that should keep kindly and tolerant Fifties sci-fi buff viewers just a little agog”. Mark David Welsh praises the performances and the effort that has gone into presenting the science in the first half of the film. However; “the real problem here is that, by the time all this is over, we’re almost an hour through the film! The drama that remains and the resolution of the mystery is fairly perfunctory”. And Dennis Schwartz is not amused, giving Gog a D, or the equivalent of a 3/10 star rating: “If the film was funny, or its technology was more interesting, or if the killings weren’t so melodramatic and the acting not so staid, and the patriotic jingoism wasn’t so shrill, I might have found this film bearable.”

Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant is a lot more forgiving, handing out the equivalent of a 3/4 star rating. Erickson is especially interested in the ideological angle of the movie, calling Gog “a futuristic and definitely jingoistic hi-tech espionage thriller that unconsciously reveals the galloping militaristic paranoia of the time”. He continues: “Disturbingly enough, the sabotage spy plane’s mission is to stop the Americans from putting that helio-death ray into orbit. The plan is to use the heat ray weapon as a threat against the Enemies of Freedom and thereby insure the peace. The OSI’s solution to the Cold War, therefore, is for the United States to militarily dominate the world. The last scene shows the armed space station being sent up in a rocket — a Nazi V2, ironically. GOG remains an ideological souvenir from a time when the H-Bomb lifted international tensions to a new level. The prescription is always the same: more secrecy, better bombs and space research to dominate the globe with ‘peacekeeping’ weapons. The happy ending of Gog reinforces the climate of Cold War terror.”

Despite the film’s flaws, I remember being quite enthusiastic after watching Gog for the first time, but subsequent viewings have failed to capture the same excitement. My first reaction may have simply been down to the fact that I had been wading through what felt like an endless stream of grainy black-and-white, low-budget films with scripts that felt like they were cooked up by the same juvenile audiences they were catering to. Suddenly, here was a beautifully restored film in eye-popping colour, with new ideas and a feeling that the screenwriters actually cared about the science. The fact that most of the movie was essentially a high-school science lesson rather than a dramatic film didn’t really bother me. But after the novelty had worn off, I have found myself skipping scenes to get through the movie. What you think of it will invariably depend on how much the slow beginning wears you down. Personally, I found it quite fascinating to watch how filmmakers in the day imagined future technology and science, and I thought the basic premise of the science station was extremely clever – even though it has become standard fare since. As a drama, though, it doesn’t hold up.

As with Tors’ previous two SF efforts, Gog makes you ask “what if?” All three movies are based on new and intriguing premises, they all benefit from Tors’ adult, serious take on the SF genre and they all have decent actors. While low-budget efforts, they had enough of a budget to make solid movies. But all three fail because the scripts fail to live up to the ideas, and because Tors hired inexperienced directors in order to cut costs. The first to movies were co-written by Tors and Curt Siodmak. Now, Siodmak has a sort of legendary shimmer among horror and SF fans because of his work on The Wolfman — in my opinion an overrated film. Like Tors, Siodmak often had interesting ideas, but failed to turn them into quality screenplays. He was at best a middling screenwriter. Gog Was co-written by Tors, Tom Taggart and Richard Taylor. Taggart, not to be confused with the later DC comic artist, was a minor playwright of farces. There are too many Richard G. Taylor’s who write books out there to get any decent info on the second writer, but his IMDb credits list only a minor western and a couple of TV episodes beside Gog. Editor Herbert Strock is the link between all three movies. The first was directed by Curt Siodmak and the second by its star Richard Carlson. In both cases, there’s speculation that Strock did at least some of the direction, and on Gog Tors finally gave him the chance to direct his own movie, and the results aren’t necessarily any better than before. So what if? What if Tors had had a proper screenwriter on hand? What if he had used a real director on his films instead of wannabe-directors to cut costs? What if he would have sold his ideas to a major studio? Robert Wise, who directed The Andromeda Strain had directed The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review) just three years prior. Imagine if he had instead directed Gog!

Perhaps not remembered as one of the great Hollywood stars today, but still Richard Egan was a very popular leading man in both historical action epics, romantic comedies and crime dramas in the late fifties and early sixties. In 1954 he starred in Demitrius and the Gladiators and went on to The View from Pompey’s Head (1955). In 1956 he starred as Elvis Presley’s brother in Love Me Tender, and went on to make A Summer Place in 1959, and the year after that saw him as Dr. Chilton in Disney’s Pollyanna. One of his most memorable roles is as legendary King Leonidas in the 1962 rendition The 300 Spartans, the hugely influential, if flawed, film, that inspired Frank Miller to make his graphic novel 300, in turn leading to a popular meme of Gerard Butler shouting ”Red Sauce on Pasta!” (2006) before kicking an man into a well.

After this Egan became a popular leading man in the TV series Empire (1962-1964) and Redigo (1963). In the late sixties his career dwindled somewhat, and he mostly appeared in B movies and as a TV guest star, until he landed a recurring role as Sam Clegg II in the Washington drama Capitol in 1983, a role he held until his death in 1987. Egan was known as a generous actor, and was a favourite among stunt men, one of the few to be bestowed with the informal title ”honorary stuntman”.

Herbert Marshall is steady in his role as top egghead, just as he was in Riders to the Stars, even if he seems to be struggling to remember his lines on occasion. Marshall was a star name on the roster, a WWII hero and a former popular leading man. More about him in the review of Riders to the Stars.

Constance Dowling was Ivan Tors’ girlfriend and future wife, whom he unfortunately forced on the film as leading lady. After a few roles in movies in the late forties, her career failed to take off, and in the fifties she mainly appeared in guest roles in TV series, but apparently Ivan Tors thought she had the makings of stardom. Herb Strock describes her as a very nice person, who never took advantage of her relationship with the producer, but adds: ”I don’t know if she was a very good actress”. She’s stiff as a board throughout the film, and there is no chemistry between her and Egan. She dropped out of acting after this movie.

John Wengraf, playing the computer scientist, was one of the many European actors fleeing the Nazis to Hollywood in the late thirties. He initially moved to Britain in 1933, but struggled to find work. However, he jumped across the pond with a troupe playing on Broadway and decided to stay in America, and relocated to Los Angeles. As a native of Austria he had no trouble finding work as a Nazi in Hollywood films during the war, ironically portraying the very people he wanted to get away from. When the war ended, Wengraf had established himself as a reliable character actor with a haughty and intelligent charisma, but seldom got more than bit-parts and small supporting roles in either A or B movies. Science fiction fans may know him as the German scientist among the international crew of a moon rocket in the famously bad Columbia picture 12 to the Moon (1960). At 57 Wengraf was still a very handsome and charismatic actor in 1954, and it is something of a mystery why he never advanced further in his Hollywood career.

Character actor William Schallert is good, as always, as Wengraf’s assistant. For sci-fi fans Schallert is something of a cult actor because of his numerous bit-parts in science fiction from 1949 all the way to 2010. He appeared in an episode of the TV show Space Control in 1951 before The Man from Planet X (1951, review). He went on to appear in Captive Women (1951, review), Invasion U.S.A (1952, review), Port Sinister (1953, review), the film serial Commando Cody: Sky Marshal of the Universe (1953), Tobor the Great (1954, review), Them! (1954, review), The Monolith Monsters (1957, review), The Story of Mankind (1957), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review), mostly in small bit-parts. He had an actual substantial role as the head of CIA in the underrated A.I. movie Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), appeared as Martin Short’s doctor in the hilarious sci-fi comedy Innerspace (1987).

Philip Van Zandt is equally great in his role as the shifty, womanising death ray creator, and brings a nice bit of wry humour to the proceedings. Van Zandt was one of the great character actors of the golden age of Hollywood, and worked with directors like Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles and Joseph von Sternberg. Remarkably, throughout his over 300 film and TV appearances, he never once worked in a really bad production – his lowest rated film on IMDb has 4.6/10 points. He also appeared in Invisible Agent (1942, review), House of Frankenstein (1944, review) and The 27th Day (1957, review).

Michael Fox appeared in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953, review), as well as The Magnetic Monster and Riders to the Stars. He also appeared in Conquest of Space (1955, review), War of the Satellites (1958) and The Misadventures of Merlin Jones (1964), as well as a number of TV series. He is one of the most memorable actors in Gog as one of the scientists who freeze to death. Fox has a lot of praise for Ivan Tors in an interview with Tom Weaver, calling him an old-fashioned filmmaker who knew how to make films, was extremely well prepared and had a wonderful imagination. The only bad thing he has to say is that Tors tended to write extremely talky scripts, since he was adamant that they should cram in as much actual science in them as they could. However, he says that he thinks that both Riders to the Stars and Gog were extremely well-made movies; ”they’re talky, but they all have some kind of basis in fact”. Fox further goes on to praise Richard Egan, who he says was a good actor and a very nice man, although ”he was prone to swagger, a little bit”.

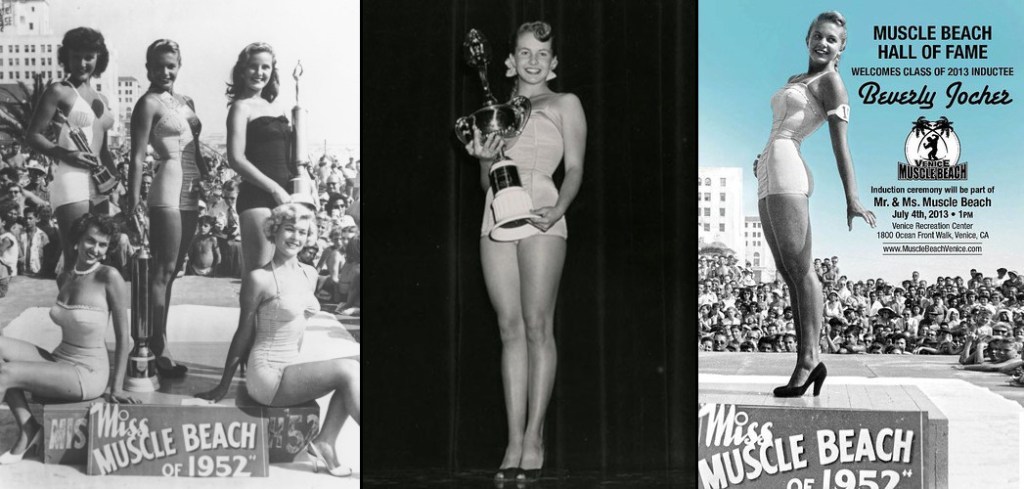

In the film we also see Tom Daly in a small role, whom we have seen previously in The Man from Planet X) and in Willie Wilder’s Phantom from Space (1951, review). Marian Richman, getting frozen alongside Michael Fox, actually does a very nice job as a no-nonsense scientist. Her film career never caught on, though, as she barely has a dozen credits for small parts. The three actors – or acrobats – playing the human test subjects in the weightlessness and the G-force scenes are Alex Jackson, Beverly Jocher and Patty Taylor. Jackson was a seasoned stage performer both in the US and the UK, and appeared both as a dancer, acrobat and in speaking roles. He can be seen in And Here Come the Girls (1953) as an adagio dancer, and as Bobo in The Lone Ranger (1955). Beverly Jocher could carry three adults on her shoulders by the age of 10, as she grew up next to the famed Muscle Beach in Santa Monica. There she became part of that pioneering group of body builders and strongmen and -women. She trained as an acrobat, fitness model and weight lifter, and was proclaimed Miss Muscle Beach in 1952, at the age of 16. She appeared in numerous TV shows, and probably films, although IMDb gives Gog as her only credit. Taylor also appeared as an acrobat at least in The Veils of Bagdad (1953).

The main robot actor was a man called Billy Curtis, something of a legend among short actors. Curtis played the hero in The Terror of Tiny Town (1938) and the Munchkin Father in The Wizard of Oz (1939), and had a number of memorable performances in both A and B films in the forties and fifties. One of the more unusual ones was in Howard Hawks’ influential sci-fi movie The Thing from Another World (1951, review), where he appeared briefly as the Thing in the final scene, where the monster shrinks as it is electrocuted. He also appeared in Superman and the Mole-Men (1951, review), Invaders from Mars (1953, review), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), played a Martian in Angry Red Planet (1968) and a child ape in Planet of the Apes (1968). On TV he appeared in the sixties Batman series and the eighties reboot of The Twilight Zone, among others. He may be best remembered to a younger audience starring opposite Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter (1973).

Billy Curtis was one of the champions of the rights of diminutive actors in Hollywood, and fought for the right of short actors to enter the Screen Actors Guild. He demanded the same pay and treatment as any other actor, and refused to take any shit on set. Michael Fox remembers that Curtis was also something of a ladies man, and always had women around him, and he always puffed on a huge cigar; ”half as big as he was!” Curtis had something of a reputation as being a difficult actor to work with, or as Fox puts it: ”He was a pain in the ass!” But he admits that Curtis had a very difficult job, partly because the robot suit got extremely hot under the lights.

Art director William Ferrari had won an Oscar for Gaslight in 1944 and an Emmy for the historical documentary reenactment series You Are There in 1953. He became a staple in sci-fi, designing sets for The Lost Missile (1958), The Time Machine (1960) and Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), as well as for the TV series Science Fiction Theatre (1955-1957), Out There (1959-1961) and The Twilight Zone (1959-1964).

Janne Wass

Gog (1954, USA). Directed & edited by Herbert L. Strock. Written by Ivan Tors, Tom Taggart, Richard G. Taylor. Starring: Richard Egan, Herbert Marshall, Constance Dowling, John Wengraf, Philip Van Zandt, Valerie Vernon, Stephen Roberts, Byron Kane, David Alpert, Michael Fox, William Schallert, Marian Richman, Jean Dean, Tom Daly, Billy Curtis. Music: Harry Sukman. Cinematography: Lothrop B. Worth. Art direction: William Ferrari. Costume design: Valerie Vernon. Makeup artist: Ted Larsen. Sound effects editor: Cathy Burrow. Scientific research: Maxwell Smith. Produced by Ivan Tors for Ivan Tors Productions.

Leave a comment