When the invisible brain monsters finally become visible in the film’s last 10 minutes, this British 1958 effort becomes one of the most memorable monster movies of the 50s. Unfortunately, the rest of the picture is hardly worth remembering. 4/10

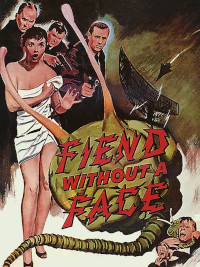

Fiend Without a Face. 1958, UK. Directed by Arthur Crabtree. Written by Herbert Leder. Based on short story by Amelia Reynolds Long. Starring: Marshall Thompson, Kim Parker, Kynaston Reeves. Produced by John Croydon & Richard Gordon. IMDb: 6.1/10. Letterboxd: 3.1/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 6.4/10. Metacritic: N/A.

The US Air Force is experimenting with a nuclear-powered radar, as part of a joint US-Canadian missile defense system, at the small Canadian village of Winthrop. Security officer Major Cummings (Marshall Thompson) has his hands full with trying to convince the superstitious locals that their cows failing to give milk has nothing to do with radiation. Things come to a point when a local experimental farmer, Jacques Griselle (Eddie Boyce), is found dead under mysterious circumstances.

So begins Fiend Without a Face, a British 1958 SF/horror “meller” produced by John Croydon and Richard Gordon, and directed by Arthur Crabtree. The movie is based on a 1930 short story by Amelia Reynolds Long called The Thought Monster, and retains the major beats of its literary inspiration, while adding quite a lot of its own material to the sleek original story. Fiend Without a Face was distributed in the US by MGM. It is a film that is ususally remembered only for its final ten minutes, in which the menace of the movie, the jumping, tentacled brains, appear.

Cummings and his colleagues, Col. Butler (Stanley Maxted), Captain Chester (Terry Kilburn) and military doctor Warren (Gil Winfield) want to do an autopsy on Griselle, the dead farmer, but are thwarted by the mayor (James Dyrenforth) and Griselle’s pretty sister Barbara Griselle (Kim Parker), who won’t allow it. However, they don’t need to wait for long for a dead body to examine, as two more farmers are killed by some unseen menace, which seems to be crawling along the ground, making ominous slurping sounds, and attacks them at the neck. And when the town mayor himself falls prey to the monsters, the whole town of Winthrop is in an uproar, with many blaming the military installation for their troubles. Dr. Warren is at a loss to explain the deaths, as they seem to have been caused by “some sort of mental vampire”, that has sucked the brains and spinal cords out of their victims.

Meanwhile, Cummings spends a lot of his time doing his own “investigation” of Ms. Griselle, who works as an assistant to the eccentric scientist Professor Walgate (Kynaston Reeves), who specialises in mind-over-matter research, such as telepathy, psychokineses and what the screenwriters call “sibonetics”. After a few twists and turns — one involving a mob led by the town lawman Gibbons, who is also Griselles suitor, searching the woods for a supposed renegade soldier whom they suspect for the killings — Professor Walgate finally admits to having (accidentally) created the monsters. Walgate has been experimenting with giving corporeal form to his thoughts by leeching off the military power plant, supercharging his brain. However, after successfully creating an invisible being in the form of a human brain, he has realised that he has created a monster — in fact: several monsters.

The film’s climax comes as the collected lead characters are gathered at Walgate’s house, and Walgate proposes to shut down the plant in order to deprive the monsters of the energy they feed on. However, the “mental vampires” have smashed the nuclear rods. Not only is the plant now impossible to shut down, it is also operating at a dangerously high capacity. So high, in fact, that it turns the fiends visible. They have now gathered outside Walgate’s house, and are hanging from trees and crawling on the ground. Cummings hatches a crazy plan to blow up the power plant’s control room, thus shutting down operations, however, he must first get past all the brain monsters. The rest of the team board up the windows and doors of Walgate’s house, while the fiends beging attacking, resulting in a visceral last stand with crawling brains flying in through chimneys and windows, while the small group of heroes defend themselves, guns blazing — hoping that Cummings will succeed in his heroic mission.

Background & Analysis

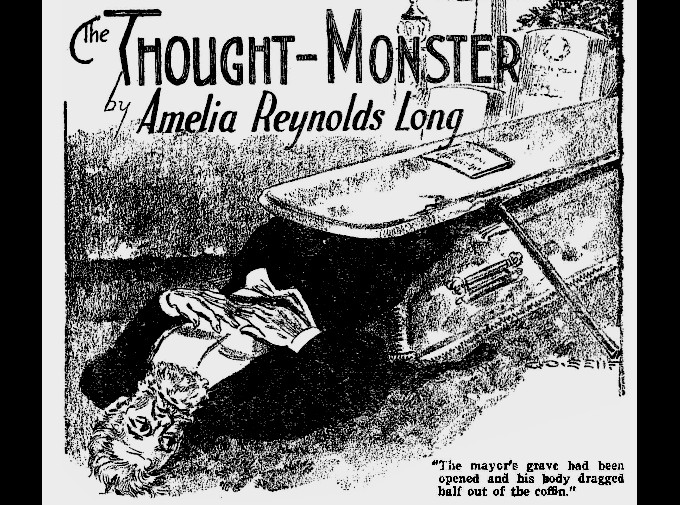

Fiend Without a Face traces its backstory to a short story published in the March issue of Weird Tales magazine in 1930, titled The Thought Monster. It was written by American author Amelia Reynolds Long, a rather prolific and quite successful writer of pulp science fiction and fantasy stories in the 30s and early 40s, who had even greater success when she switched to mystery stories in the 40s. The Thought Monster was her third published story. While rather obscure even today, Long’s legacy as an SF pioneer might have been completely forgotten, had it not been for Forrest J. Ackerman, who in the 50s approached her with an offer to become her agent, promoting her old stories for magazines, films and reprints.

Ackerman thought that The Thought Monster might make for an interesting movie idea for American International Pictures, the leading low-budget SF studio of the late 50s, but studio head James Nicholson passed on the offer (invisible monsters were always tricky on film). However, British-born AIP producer Alex Gordon was intrigued and passed the story over to his brother Richard, who, after spending time in New York and Los Angeles, was setting up shop as a producer in London, alongside John Croydon. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Richard Gordon says he liked the story, and thought it would make a good co-feature for a Boris Karloff film he was making in London, Haunted Strangler (1958). Gordon turned the story over to Herbert Leder, at the time primarily known as a producer of comedy and children’s TV shows. Fiend Without a Face became his first movie screenplay. Originally Leder had intened to direct the film, but red tape demanded a British director. Arthur Crabtree was reeled in – Crabtree had been a successful cinematographer and later director of musical comedies and historical melodramas in the 40s, but his career was on the wane, in fact Fiend Without a Face was one of his last movies. Crabtree had no experience with either horror, science fiction or monster movies, but his name had some marquee value in the UK.

According to star Marshall Thompson, Crabtree turned up on set on the first day of filming, took one look at the script and informed the cast and crew that he refused to do the film. He walked off set, and the producers needed several days to convince him to return, citing contractual obligations. Thompson says that during those days, Thompson directed the film himself.

The Thought Monster differs quite a bit from the film, but the gist of the story is still there, fairly intact (you can read it here). In Amelia Reynolds Long’s story, a number of inhabitants in a small town, including the mayor, die from fright during the night. The lead investigator, Gibson, goes out with a posse in the woods to catch what he thinks may be a serial killer. However, Gibson disappears and turns up days later as a mindless lunatic. Then a paranormal investigator, Cummings, turns up, who suspects some supernatural force at work. He starts investigating a recluse psychologist, specialising in parapsychology, and even though he suspects that Professor Walgate knows something, he doesn’t push it, but waits for Walgate to come to his own conclusions. Instead he instructs the inhabitants to put up purple lights, as these should ward off supernatural beings. For a time, it seems to work, as the deaths stop occurring. However, the “thought monsters” keep killing all the people who visit the town, and don’t have purple lights, so something still needs to be done. There’s also a break-in at the local graveyard, where someone has dug up the mayor. Cummings then receives a call from Walgate, telling him to visit him in half an hour. When Cummings arrives, he finds Walgate’s house empty, with a journal on the desk addressed to him. The journal catalogues Walgate’s experiments with trying to materialise thought into a being of its own. For the purpose, Walgate has built a lead-lined room in which to contain the thought beings. But halfway through the experiment, his maid opens the room. Walgate thinks the half-formed beings have “evaporated”, and abandons the project. When the killings start occurring, he doesn’t immediately connect them with his experiments, only later does he start to feel a presence in his own house. He confesses to having dug up the mayor, in order to do his own autopsy. Walgate realises that he has created monsters — mental vampires he calls them. He writes that he intends to lower his mental guards and draw the thought monsters into the lead room and shut the door behind him, sacrificing himself so that he can deprive the beings of their sustenance, thereby killing them. When Cummings enters the lead room, he immediately feels that the thought beings are gone, but to his horror sees Walgate — the formerly brilliant man now a mindless lunatic.

Long’s story does not belong up there in the Pantheon of immortal SF short stories, but it is a brisk, crisp and intriguing little tale in the borderland between science fiction and paranormal/parapsychological horror that was popular at the time — not too far removed from themes that authors like H.P. Lovecraft dabbled in. Its economical and matter-of-fact, sort of detached, storytelling reminds of some of the more humorous pieces by Edgar Allan Poe, such as The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar or Some Words with a Mummy. The difference here is that Long describes a rather intricate plot with many twists and turns that takes place over a longer period of time in a very brief retelling. Central characters enter and exit the story over a stretch of only a couple of pages and big, dramatic events are covered in no more than a couple of sentences. Half of the story, basically, is told more or less as background information, and a good part of the other half consists of Walgate’s journal. This is not necessarily a complaint, but it would have been interesting to see the story fleshed out into a longer version, even a novella. Or indeed a feature film. However, Herbert Leder was not a writer of Long’s calibre, and anyway, Fiend Without a Face is not really a faithful adaptation of the story.

First of all, Leder has added the entire plot with the military base and the nuclear power station, also changing the nature of the menace — slightly at least. Gibson the investigator is turned into Gibbons, the local lawman, who is more an antagonist than anything else, and really only a minor character in the movie. In the film, he is Cumming’s romantic rival and a rabble-rouser blaming the Air Force for the deaths. But like Gibson, Gibbons disappears in the woods while looking for a murderer, and turns up later, a mindless lunatic (in one of the more effective scenes of the film). Cummings is changed from a paranormal investigator into an Air Force Major, and is given a romantic interest in Barbara Griselle, Walgate’s assistant — a completely new character. The showdown at the end is an original Leder creation, as is the fact that the monsters turn visible — which they eventually must in a 50s science fiction film.

Curiously, most of the story is still basically intact. The strange deaths in the woods at night, including the mayor. The posse led by lawman Gibson/Gibbons into the woods, his disappearance and reapperance as a zombie. The professor working with parapsychology, who is a kindly and helpful sort, but is slow to give out knowledge. Leder has even retained the break-in at the local crypt, even though it serves no purpose in the film. And while the ending is drastically different, the creatures are killed in both instances by a heroic deed which deprives them of their sustenance. In the book’s case: thoughts, in the film’s: nuclear power.

That is not to say that this is necessarily a good adaptation of the story. A major problem is that the short story is quite short, and written in a matter-of-fact, almost reportage style, with no character development and very little emotional punch. The main drama is related either by the story’s narrator almost as flashbacks, or through Walgate’s journal. Herbert Leder has tried to keep all the main beats of the story, but has a hard time incorporating them into his own frame story about the military investigation into the deaths, framed by the nuclear experiments. Two of the main beats of the story, Gibson/Gibbons’ disappearance and reappearance, and the break-in at the crypt, have been fleshed out from brief mentions in the story to long dramatic scenes in the film. Unfortunately, these stop the main plot in its tracks and bogs the middle of the film down. Gibbons is too obscure a character for us to care what happens to him (and apparently an asshole at that), but we still have to follow him and his posse for a full five minutes looking for a renegade soldier that we the audience know isn’t there. The graveyard bit comes completely out of the blue in the movie, when Cummings — for no apparent reason — decides to visit the mayor’s grave and finds Walgate’s pipe, and gets trapped — apparently accidentally — in the crypt by a panicked Walgate. We the audience don’t understand why Cummings goes to the crypt, nor why Walgate would be there (and even less, why Cummings would suspect finding Walgate there), and no new information is relayed in the scene. It’s just there because it’s sort of in the short story, and the film needed padding in order to stretch into 70 minutes.

The characters in the story are featureless, and Leder has not done a particularly good job at adding features to them. Cummings’ personality seems to shift to a and fro depending on what the story needs (him slugging Gibbons over a romantic rivalry seems wholly out of character, especially since he has hardly got to know Barbara Griselle at that point), Captain Chester is a stock comic relief, Barbara Griselle is a standard B-movie ingenue and Professor Walgate’s character comes almost entirely from the colourful performance by Kynaston Reeves.

Much is made of the radar experiments — the entire 10 first minutes of the movie are is devoted to these, but they fail to play any part in the rest of the film, aside from the fact that they are nuclear powered. There is no reason why the film would have to be placed at an Air Force base. It could just as well have been an ordinary nuclear power plant. There’s a meet-cute between Cummings and Griselle getting out of the shower wearing a towel — a scene that is present in the film only for the sake of the trailer. The supposed romance between Cummings and Griselle is nowhere to be seen on screen. They just suddenly kiss out of the blue, and that’s that out of the way. Why producers kept thinking that these movies needed a romance when none of the target audiences were there for a romance is beyond by comprehension.

The movie immediately starts off on the wrong foot, treating the audience to the same kind of stock footage of planes and rotating radar discs that had been the staple of low-budget SF movies for almost a decade, an uninspired shot of a guard sort of witnessing the first murder, and extremely dull “military officers talking exposition over a desk in front of a window” shots that these movies were full of. Things perk up a bit with the introduction of Barbara Griselle, but sparks never fly between her and Cummings, which is to be blamed more on the script than on actors Marshall Thompson and Kim Parker, who just don’t have much to work with.

However, there is a nice mystery plot that holds up fairly well on a first viewing, as the audience really doesn’t know quite what is going on. Arthur Crabtree’s direction is, for the most part, unremarkable, but he succeeds in building up some degree of suspense, at least in parts of the movie. There are standout moments, such as when Gibbons suddenly turns up, grotesquely deformed and emitting mindless moaning sounds, or when Col. Butler accuses the dead Jacques Griselle of keeping a detailed journal of all the Air Force base’s flights, and Barbara points out that he was journalling the instances of when his cows were giving out poor milk.

There are a whole number of scientific gaffes in the movie, which, of course, is the case with almost any 50 SF movie. For example, the bizarre notion that it would require an entire nuclear power plant in order to power a radar. The film assures us that there is no radiation or fallout from the plant, but still, somehow, both Walgate and the brain monsters are apparently able to feed off the nuclear power straight off the air. Perhaps the most famous nuclear-related gaffe is when Cummings says he can shut down the nuclear pile by dynamiting the control room. Yeah, dynamite is definitely the solution when you’re having problems at your nuclear pile… Another fun detail is that screenwriter Leder apparently didn’t know how to spell “cybernetics” — and spelled it “sibonetics”. This leads to Marshall Thompson pronouncing it see-bow-netics [sɪboʊnet̬ɪks]. The faulty spelling even shows up in close-up on the cover of one of Walgate’s books.

As for the movie’s message or themes, if any, Richard Scheib at Moria has an interesting take, placing Fiend Without a Face in the context of “1950s science-fiction Cold War paranoia nuttiness”. According to Scheib, the movie “crudely [manages] to symbolise [an] amazing strand of anti-intellectualism”. He writes: “The 1950s were a time when any type of thought that did not conform to very conservative lines was treated suspiciously and intellectuals were thought to be dangerous. Thus it is interesting to watch the progression the film makes wherein disembodied (ie. unrestrained) thought automatically develops a will of its own and becomes evil and monstrous. If one can make the imaginative leap to substitute student radicals for the hopping brains being shot down at the climax then the film becomes appallingly prophetic of the Kent State student riots in the 1960s and what they represented.”

Scheib’s analysis is interesting, but somewhat far-fetched (as he himself concedes), considering that it would have required both screenwriter Leder and director Crabtree to put some actual thought (pardon the pun) into the themes of the script, and this does not seem like a movie that is trying to make an intellectual (or anti-intellectual) point. Sure enough, one can gleen as much about the intellectual and cultural climate at the time of a film’s production from what it inadvertedly says as from what it actually tries to say. But I doubt that Leder tried to say much about radicalism or conformity with Walgate’s thought experiments. Rather, I suspect, he was falling back on the short story, which was inspired, more than anything, by the ideas of parapsychology, which were very much in vogue in the 1920s and into the 1930s. Seen in their historical context, Long’s ideas on thought materialisation are not metaphorical, but taken directly from a field of quite serious research that was only beginning to be viewed as pseudoscientific at the time of her writing the story.

In Twice the Thrills! Twice the Chills, Bryan Senn singles out the theme of nuclear paranoia, and the fear of what might happen if, for example, a foreign power might gain control over a nation’s nuclear reactors. This, I think, hits a bit closer to home, as this was a theme that Leder himself added to the story. But if there is a message here, it is, as Senn also points out, not very strong, even somewhat garbled. Leder doesn’t seem to take any particular stand in the issue of nuclear power. Rather, I’d say that as with so many other late 50s SF movies, the producers and screenwriters simply regurgitated familiar tropes, in this case the nuclear threat, without putting any deeper thought into it.

All in all, it’s a script that suffers from a lack of direction. It sort of hops from one incident to the next, from one idea to another, as if unsure of what the movie is really about. As Walgate finally fesses up to his thought experiments, the movie stabilises itself, leading to the energetic finale. But Leder has struggled to fill out the rest of the movie’s 50 minutes, which has led to a feeling that most of it consists of drawn-out padding anticipating the climax.

It’s unfair, really, to critique the acting, as none of the actors have much to work from. Marshall Thompson comes across as a John Agar clone, a jovial, good-natured, middle-aged, decent-looking but thoroughly bland hero. Richard Gordon tells Tom Weaver that the choice of Thompson was informed primarily by the fact that he was one of the Hollywood B-movie leading men that was available for travelling to England at the time of shooting. Kim Parker comes off fine in the only lead of her short acting career. The rest of the cast perform their stock characters with various degrees of success. Kynaston Reeves brings a twitchy energy to his professor, and does a good job of portraying the frailty of the scientist, thoroughly worn out by his dangerous experiments. Terry Kilburn ladles on the mugging as the comic relief, and there’s a few short scene-steals by later character actor extraordinaire Michael Balfour. Peter Madden is very good as the sympathetic town coroner. The role is redundant, but Madden makes it memorable.

The real stars of the film are the special effects and sound designers. Peter Davies’ sound effects for the thought monsters is nothing short of brilliant. Of course, as the monsters remain invisible for most of the film, their presence is mainly signalled by sound. Davies has created a wet, sloppy, slurping but at the same time menacing “SLURGH-SLURGH-SLURGH” effect for the creatures, and its effect is heightened by the fact that it is turned up really loud on the soundtrack. While over the top and slightly cartoonish, it is also highly effective, and very icky.

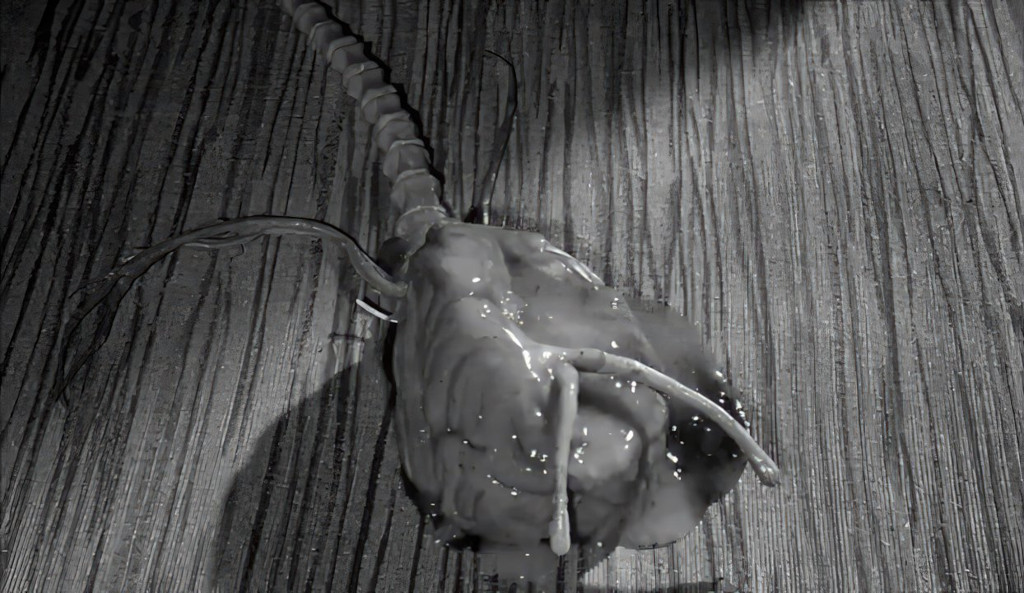

However, what the film is primarily — really only — remembered for, is the last 10 minutes when the monsters become visible, and are revealed to be bizarre-looking brains with long tentacles or “feelers”, spindly legs and a spinal chord which they use to propel themselves forward, a bit like larvae or caterpillars. It is extremely cartoonish, and at the same time comical and disturbing — a truly bizarre creation. The design itself would have been enough to make the monsters iconic, but what really put them on the map was the very impressive stop-motion animation by Austrian-German artists Baron Florenz Fuchs von Nordhoff and Karl-Ludwig Ruppel, working under the moniker Ruppel & Nordhoff.

According to one story, Flo Nordhoff sat in on a production meeting when the menace of the film was being discussed, and doodled away as the producers and the director discussed the thought monster. At one point he leaned in and showed the group a sketch of the brain monster, and the whole room was taken aback. Nordhoff was immediately hired to create the effects along with his associate Ruppel. The actual animation work was done in the artists’ studio in Germany, and the special effects pushed the budget of the movie from £50,000 and £80,000, as high as the top-billed Karloff movie, and also caused the movie be delayed by a couple of weeks. But the efforts were definitely worthwile.

The animation in Fiend Without a Face is lightyears better than one is used to seeing in a low-budget movie of this kind. Granted, it is a tad jerky at times and compared to the intricate creatures created by Ray Harryhausen and the likes, the brain monsters are certainly rather simple puppets. Nevertheless, considering the stodginess of the rest of the movie, the last 10 minutes seem to belong to another film entirely. Ruppel & Nordhoff’s animation lifts the entire movie a whole notch during the ending of the movie. Silly and menacing at the same time, the brain monsters never feel like the clumsy rubber monsters of so many other film of this type. They are agile, fast, and seem to actually co-exist with the actors in the same room. The monsters are animated in such as way as they seem to have purpose, motivation and personality. In one scene, they struggle to get in through a boarded-up window. One of them grabs a hammer from the windowsill and tries to pry the boards open. When this fails, the group use their spinal chords as tentacles that they wrap round the boards and break them open. Another scene sees an injured brain monster drag itself toward the dynamite at the nuclear facility and try to blow out the fuse (one can ask with what it is blowing, but that’s hardly relevant).

Another thing that make these last scenes stand out is the surprising amount of gore on display. Granted, not human gore, but monster gore, but still. When the brain monsters are shot, blood and brain matter ooze, bubble and splatter all over the walls and ceilings (apparently this was raspberry jam made by Mrs. Nordhoff). In England, the film had to be re-cut after the censors viewed it, even though it was given the X rating. And even so, the fact that the film got released was supposedly even up for debate in Parliament.

But it’s not only the animation that raises the quality of the movie in the end. It seems the action also kicks director Crabtree and editor Richard Q. McNaughton into a new gear. The editing during the final battle is frantic, dynamic and dramatic, quickly cutting between the defenders firing their guns, the the monsters attacking or getting splattered over the walls, dropping from the ceiling, flying in through windows, attaching themselves to the necks of their victims (here the rubber substitutes work very well as stand-ins for the animated monsters).

The final 10 minutes of Fiend Without a Face is one of the best in a 50s science fiction movie, all categories. It’s just a shame that we must slog through 60 minutes of uninspired potboiler plot before we get there.

Reception & Legacy

Fiend Without a Face was released in May, 1958 in Britain by Amalgamated Pictures and in October in the US by MGM, in both countries as a double bill with Richard Gordon’s owns Haunted Strangler starring Boris Karloff. In the UK it was released with the infamous X rating (meaning you had to be an adult to see it), and in many European countries it received a similar K18 rating. Sweden banned the film outright. Censors demanded cuts made in the British version of the film, but nevertheless, UK critics were reportedly appalled at the gore of movie, and wondered aloud how the film made it past the censors. According to several anecdotes, the British film censors’ negligence to ban the movie was even up for debate in Parliament, although I have found no real sources for this claim. Most of my sources seem to quote producer Richard Gordon for this information. Gordon, for his part, was over the moon over the furore. He muses to Tom Weaver that this was publicity that money couldn’t buy. The double bill also did fairly well at the box office. According to MGM records, the two films earned $350,000 in the United States and Canada, and $300,000 in England and elsewhere, with MGM making a profit of $160,000.

In the US trade press reviews were mediocre to bad. The Motion Picture Daily, seldom giving movies bad reviews, wrote that Fiend Without a Face was “well and logically constructed, capably acted and directed”. In a fair review, “Powe” in Variety noted that the film would likely go down well with its intended audience: “It oozes and gurgles with Grand Guignol blood and crunching bones, easily one of the goriest horror pictures in the current cycle. Story, direction and acting are primitive, but the macabre effects may satisfy the blood-thirsty.” The critic for Harrison’s Reports, however, was not entertained, noting that up intil the cory climax, the film was “fairly interesting in the usual fantastic sort of way”. But the final 15 minutes, writes the critic, were merely “revolting” because of the gore: “All this is depicted so vividly that it makes the viewer sick to his stomach. Because of its excessive gore, the picture is too unpalatable to be classified as entertainment.”

Most critics today echo Bill Warren’s verdict in Keep Watching the Skies!: “Although not bad overall, the film has a very conventional plot structure, adding carnivorous brains; the movie is largely uninteresting until the fiends make their appearance. The acting is mediocre, the dialogue is perfunctory.”

In Twice the Thrills! Twice the Chills, Bryan Senn calls the movie “not only clever and strikingly original, but unforgettable — at least in the last ten minutes. Unfortunately, it takes quite a bit to get there…” DVD Savant Glenn Erickson says: “The truth be known, Fiend Without a Face is a lacklustre and formulaic monster movie. Marshall Thompson is more engaging almost anywhere else and the rest of the English cast, probably because of the flat and static direction of Arthur Crabtree, can best described as enthusiastic to no positive effect. The photography is dull and the plodding development of the mystery offers little suspense and few thrills. Then comes the remarkable finale. […] This ending has kept fans happy for 40 years, it’s true, but it’s no masterpiece”.

Richard Scheib at Moria writes, in a 2/5 star review: “Aside from its subtext, there is little that is worth watching in Fiend Without a Face, despite the minor reputation it has – which all rests on the climax. Arthur Crabtree directs in a flat and dreary style, and the film is devoid of any real drama.” British critic Kim Newman says: “Besides the business with the military/scientific base, which is a glorified red herring, Leder only adds conventional padding material”.

In 2001, Criterion released the movie on DVD with much fanfare, calling it “a high-water mark in British science fiction. Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster asks himself: “Is this one really a great classic, worthy of the Criterion Collection treatment it got? I’m not entirely certain. It is much better than the overrated Fifties version of The Blob which also has been released by Criterion, and it sticks in the mind a lot longer and harder than most of the SF films of the era. Ironically, it reminds me just a touch of Ray Harryhausen’s Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, not because they particularly resemble each other, but that the two films represent some of the most extravagant — and effective — effects work seen during the era. Yet neither film has quite the same cachet as many of the other more famous Fifties SF films, even some that are nowhere near as effective. What is definitely true is that this was one of the best of the best of that Golden Age, and yet most fans haven’t seen it. Which is a shame, of course.”

Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant isn’t quite as positive: “Criterion’s lauded desire to be authoritative on the subject of cinema falls victim to typical elitist snobbery with Fiend … it being a lowly monster movie, the only possible attitude is condescension, which in this case means thoughtlessness. Elitist film criticism doesn’t recognize merit in fun monster movies, only ‘meaningful science fiction.’ […] The high-water mark in British Science Fiction after The Quatermass Xperiment? Almost all of the films named in the ‘extra essay’ in the extras section are far better, especially Quatermass 2 and The Abominable Snowman, not to mention These Are the Damned and The Day the Earth Caught Fire. Fiend, an acceptable movie that need make no apologies to anyone, is not the victim of Criterion’s attitude .. that’s Criterion itself.”

Cast & Crew

Executive producer Richard Gordon was the brother of slightly better known Alex Gordon. The brothers both became interested in the movies from a young age, and relocated for greener pastures in New York in the 40s. Alex moved to Los Angeles, where he befriended people like Bela Lugosi and Ed Wood, and became one of the original producers of American International Pictures. Richard stayed in New York, where he set up his own company Gordon Films, importing and distributing British and international films to the US. He gradually became more film production, and ended up being the de facto producer on many films from the mid-50s onward, even if he was often uncredited for the first decade of his producing career. A friend of both horror and science fiction, he produced Escapement (1958, review), Fiend Without a Face (1958), First Man Into Space (1959, review), The Projected Man (1966), Island of Terror (1966), Horror Hospital (1973) and Inseminoid (1981).

Nominal producer on the film was John Croydon, a British production manager and producer who was active from the early 30s to the late 50s. He is best remembered today for his collaboration on the SF/horror films of Richard Gordon: Fiend Without a Face (1958), Haunted Strangler (1958), First Man Into Space (1959) and The Projected Man (1966), the latter three of which he also co-wrote the screenplays for.

Director Arthur Crabtree (b. 1900) left a secure engineering job in the late 1920s to become a clapper boy at Elstree studios, at the same time educating himself in the art of filmmaking by, allegedly, working briefly as an assistant to Alfred Hitchcock. It didn’t take long before Crabtree started working as a cameraman and cinematographer. Between 1931 and 1945 he shot close to 40 films, first at the small outfit British International Pictures, and later at Gainsborough, where he became the go-to DP for director Marcel Varnel. However, he is probably better known for photographing a number of successful historical melodramas for other directors, including The Man in Grey (1943) and Fanny by Gaslight (1944).

In 1945, Crabtree was promoted to director at Gainsborough, with the movie Madonna of the Seven Moons, and the film’s success cemented his directorial career. With the British film industry now fuelled by growing international success and ever larger quota requirements for British-made films in UK theatres, the 40s was a period in which the demand for movie directors was greater than the supply, so many screenwriters and cinematographers were promoted to directorial duties, including Crabtree. Phyllis Calvert, who starred in Madonna of the Seven Moons, as well as in another Crabtree film, They Were Sisters (1945), later diplomatically noted that she didn’t think much of Crabtree’s directorial talents. She said the actors more or less directed themselves in his early films – but they appreciated his background as a cinematographer, as he knew how to make them look good on screen.

Crabtree flourished at Gainsborough, where his eye for visuals compensated for his less competent handling of drama and actors in the studio’s lavish costume melodramas. However, as Gainsborough folded in 1951, his directorial career floundered, and he ended up working a great deal in TV, mainly directing period shows like The Adventures of Robin Hood and Ivanhoe, while the quality of his movie productions diminished, and he ended up working in genres he wasn’t necessarily comfortable in. He only made two other film after Fiend Without a Face, including the low-budget horror movie Horrors of the Black Museum (1959), produced by Herman Cohen for AIP, and filmed in the UK.

Oddly, the production credits for Fiend Without a Face doesn’t list a diector of photography, suggesting that Crabtree filmed the movie himself – and that second unit photographer Martin Curtis might have stood in when Crabtree was away having a tantrum. This is pure conjecture on my part, though.

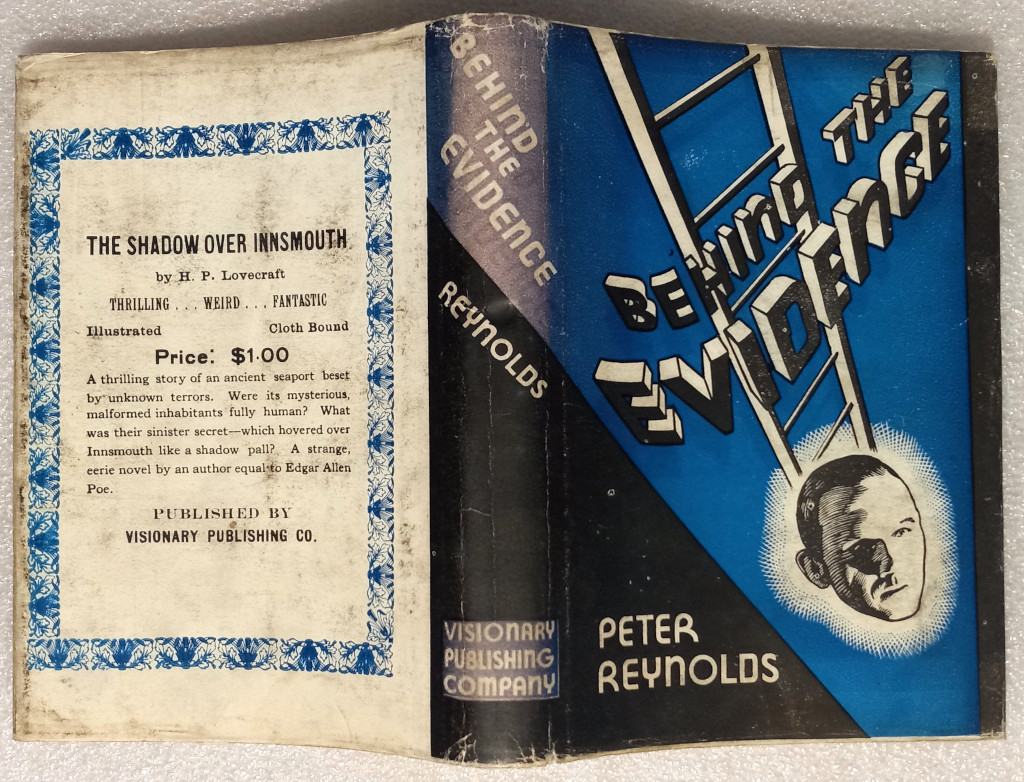

Author Amelia Reynolds Long was born in 1904 in Columbia, Pennsylvania, and lived almost all her life in Harrisburg, PA. She has been called a pioneer for female science fiction writers, although during her active period of writing SF, the 30s, she was overshadowed by the success of other writers, like Claire Winger Harris and C.L. Moore. John Clute at the SF Encyclopedia says: “Her style was crisp and fluent, and her tales inclined towards the weird”. Most of her 20+ SFF stories were published in Weird Tales, but she was also featured in a number of other magazines. In 1936, she wrote one SF novel, together with William L. Crawford, under the joint pseudonym Peter Reynolds, one of the few times she used a pseudonym. The novel, Behind the Evidence, was loosely based on the Lindbergh kidnapping, but set in a Germanic country. The novel was a re-working of one of Long’s unpublished stories, which she pulled from publication as the body of Charles Lindbergh’s son was discovered just before the story was to go into print in 1932.

In an interview with Chet Williamson for the fanzine Crumbling Relicks in 1976 (republished here), just two years prior to her death, Long explains that she lost interest in writing science fiction in the 40s, due to the fact that sci-fi had hit the comic pages: “I felt that it was sort of degrading to compete with a comic strip”. Instead she turned to writing Agatha Christie-inspired mystery novels, with which she had some modest commercial success. Some of her better known mystery books are The Shakespeare Murders (1940), Death Wears a Scarab (1943) and The Lady is Dead (1951). However, she was again frustrated with the times. The Dashiel Hammett-style hardboiled crime novel was all the rage, and her publisher wanted Long to adapt her stories to this new fad. Long tried but couldn’t make herself write the bleak, violent and cynical stories the publishers wanted. Falling back on her master’s degree in literature, Long began working as a textbook editor in the early 50s, and after a few years with writer’s block, turned her energy toward poetry, to which she devoted much of her life up until her death in 1978. Her poems were published in local papers, and the Pennsylvania Poets Society, in which she was very active, published two chapbook collections of her poems in 1974 and 1975. She is perhaps best remembered for her work collecting local poetry between two covers in the anthology Pennsylvania Poems (1977).

I haven’t read anything else by Long than The Thought Monster, which was one of her very first short stories, but judging from that, Long’s style seems to have been a lean, condensed prose focusing on ideas rather than character exploration or drama, with a witty undercurrent of humour. Richard Simms, the curator of an Amelia Reynolds Long tribute page, describes her writing as follows: “With good dialogue and a sense of high speed adventure pervading her stories, it is even more impressive how much of her science fiction and weird fantasy work still seems fresh today. Reading the stories now, one can’t help but marvel at the sheer explosion of ideas that leap out from the pages.” Even with the help of agent Forrest J. Ackerman doing his best to get her stories reprinted in the 50s, there has never been any great resurgence in the popularity of Long’s SF authorship, and she remains fairly obscure even among aficionados of early female SF authors. However, she is well-know enough that her books, often printed only in a single edition, fetch a rather steep price on the second-hand book market (I know, I wanted to buy some of them).

There is not much information about American screenwriter Herbert J. Leder, but he seems to have rattled around the US and UK film scenes in the 50s and 60s in one capacity or the other. Born in 1922 and dead in 1983, Leder at some point worked as a professor of film in New Jersey, and, according to his brief Wikipedia page, he worked at some producing capacity for a number of 50s TV shows, including Captain Video and his Video Rangers (review) and The Loretta Young Show. During the late 40s he worked as a director for the NBC show Meet the Press.

Leder’s movie credits measure about half a dozen between 1958 and 1969, when he wrote and/or produced and/or directed a handful of low-budget movies, several of them in the UK, where he seems to have been stationed for some time. About half of them are crime dramas and the other half horror/SF. In 1958, he adapted Amelia Reynolds Long’s short story The Thought Monster into what would become Fiend Without a Face. He is best known for writing, producing and directing the golem film It! (starring Roddy McDowell) and The Frozen Dead (with Dana Andrews), about frozen heads of Nazi scientists, released as a double bill in the UK in 1966 and in the US in 1967. In 1967 he also began directing another SF movie in the US. However, funding fell through mid-way through filming, and the footage sat on a shelf for five years, before producer Harry Hope resumed filming with Lee Sholem as director, albeit without the original cast or sets. The laughably amateurish film, released as Doomsday Machine, has become a cult classic.

American lead actor Marshall Thompson had a long and quite successful career, and was able to adapt and reform himself over the years, eventually combining his work in front of the camera with producing and directing. In the 50s he also racked up something of a science fiction legacy. Thompson began as a young boy-next-door in the mid-40s at Universal, mostly in smaller roles, but even managed to secure a minor lead during the last period of WWII, when many of the big stars were off entertaining the troops. He moved to MGM in 1946, and had decent supporting roles, as his IMDb bio puts it, “in perfunctory nice-guy assignments”, without ever rising to leading man status. His MGM contract was terminated around 1950, and he went freelance.

Thompson’s freelance work during the first half 50s was of varied quality, he mostly did supporting roles and a few leads in B-pictures, both for major and minor studios. 1955 was an important year, as it marked a high point with a co-lead in Universal’s war movie To Hell and Back, and another co-lead in United Artists’ Battle Taxi. The latter film left no large imprint on movie history, but it was the first collaboration with producer Ivan Tors, who would later prove instrumental for Thompson’s career. Univeral’s Cult of the Cobra (1955) was Thompson’s first tango with the horror genre.

The quality of Thompson’s films, or at least their status, diminished during the latter half of the 50s, and he found himself doing leads in minor pictures, while working ever more frequently in TV. 1957 saw him starring in a small Mexican-US African adventure film called East of Kilimanjaro, by all accounts not a very good one, but one which cemented his passion for animals and wildlife. His status as a minor science fiction notability came about in the late 50s, when he starred in three SF movies, Richard Gordon’s Fiend Without a Face (1958) and First Man in Space (1959). Most importantly, he starred in United Artists’ It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review), inspired by A.E. Van Vogt’s fix-up novel The Voyage of the Space Beagle (1959). A mediocre and in many ways clunky low-budget monster movie, it built on a novel idea of an alien monster infiltrating a spaceship, and has been claimed as a major inspiration on Alien (1979).

The mid-60s became the high point in Marshall Thompson’s career, as he directed the war film A Yank in Vietnam (1964), on the strength of which his old friend Ivan Tors hired him as director on several episodes of the animal-themed hit TV series Flipper in 1965. The same year saw the release of Tors’ family movie Clarence the Cross-Eyed Lion, where Thompson starred as Dr. Marsh Tracy, a veterinarian living in Africa with his daughter, taking care of animals. The film was based on a story treatment by Thompson. The following year Thompson appeared in another Tors film, the science fiction movie Around the World Under the Sea. However, more importantly, Thompson and Tors decided to create a TV series based on Dr. Marsh and Clarence, and the result was Daktari (1966-1969). The TV show became a surprise hit, ran for four seasons, and finally lifted Thompson into star status. Tors’ and Thompson’s animal-themed collaboration continued with the TV series Jambo (1969), which Thompson presented and narrated. In 1972 he starred in the children’s movie George, about a Saint-Bernard living in the Swiss Alps, and he had a recurring role in a TV series (1972-1974) based on the movie. In 1982 he appeared in another dog-themed film, White Dog.

After the success of Daktari, Thompson worked mainly in TV, although he found time to appear in a handful of feature films, including the SF/horror film Bog (1979), an ultra-low-budget monster movie inspired by Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review). He only worked sporadically in the 80s, focusing more on providing nature and wildlife photography for TV, and made his last film apperance in 1991.

Fiend Without a Face provided Kim Parker with the only lead of her short movie career — in which she became something of an SF staple. She appeared as one of the titular Fire Maidens in Fire Maidens from Outer Space (1956, review), which we gave 0/10 stars, and in W. Lee Wilder’s SF horror film The Man Without a Body (1957, review) and even played the lead in Fiend Without a Face (1958).

In a decent supporting part as a soldier, we see a young Michael Balfour, who appeared in over 230 films or TV shows between 1938 and 1993, mostly in bit-parts. With a “chubby, lived-in face which seemed to convey a perpetual state of bewilderment”, Balfour was always a memorable dash of colour to a movie or TV episode. He is remembered for playing one of the murderers in Roman Polanski’s Macbeth (1971) and cigar-chomping boxing referee in The Krays (1980). Although born in Kent, he early on put on an American accent in order to stand out, which may be one of the reasons for his casting as an American soldier in Fiend Without a Face (1959).

Glum-faced, gaunt Peter Madden was often seen in British films and TV series in either villainous roles or as characters with stiff upper lips. He is quoted as having said: “I’m generally cast as a baddie because I’ve got such a miserable bloody face. Thank God I never wanted to be a star.” Madden is perhaps best remembered for his brief appearance as the Canadian chess master McAdams playing against a Spectre agent in the famous chess scene in From Russia With Love (1963) and as Inspector Lestrade opposite Peter Cushing’s Sherlock in the 1964–1968 TV show Sherlock Holmes. His first SF outing was Fiend Without a Face (1958). He can also be glimpsed in the Hammer films The Kiss of the Vampire (1963), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974), as well as in the Amicus anthology Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965).

The rest of the cast is made up of rather anonymous British character and bit-part players. Kynaston Reeves as Prof. Walgate was a staple in BBC productions, starting in the 50s, and appeared in numerous films in supporting roles, without ever making a big name for himself. Comic relief Terry Kilburn had a moment of glory in 1939 in a prominent role as the adolescent John and many Peters Colley in Oscar-winner Goodbye, Mr. Chips. However, Kilburn struggled to advance his movie career as an adult and called it quits in the early 60s. E. Kerrigan Prescott co-starred in Godmonster of Indian Flats (1973), an ultra-low-budget US monster movie featuring a mutated sheep. Prolific bit-part player Victor Harrington’s greatest claim to fame is probably being one of the officials sitting around the gigantic table in the War Room in Dr. Strangelove (1964).

Assistant director on Fiend Without a Face (1958) was none other than Douglas Hickox, who would go on to become one of the foremost B-movie action directors in Britain in the 70s. He directed films like Sitting Target (1972) with Oliver Reed, the critically lauded Vincent Price horror movie Theatre of Blood (1973), the Dirty Harry-inspired Brannigan (1975), featuring John Wayne wreaking havoc on London and Zulu Dawn (1979 with Burt Lancaster and Peter O’Toole. In his latter years he worked mostly in TV, making a couple of well-regarded TV movies, The Hound of Baskervilles (1983) and Blackout (1985). Hickox died in 1988 during heart surgery, only 59 years old.

Flo Nordhoff and Karl-Ludwig Ruppel created special effects for Richard Gordon’s science fiction movies Fiend Without a Face (1958) and First Man Into Space (1959), and Nordhoff also worked on Gordon’s The Projected Man (1966).

Janne Wass

Fiend Without a Face. 1958, UK. Directed by Arthur Crabtree. Written by Herbert Leder. Based on the short story “The Thought Monster” by Amelia Reynolds Long. Starring: Marshall Thompson, Kim Parker, Kynaston Reeves, Terry Kilburn, Robert MacKenzie, Peter Madden, Gil Winfield, Stanley Maxted, Michael Balfour, James Dyrenforth, Shane Cordell, E. Kerrigan Prescott, Meadows White, Lala Lloyd, Launce Maraschal. Music: Buxton Orr. Cinematography: ? Editing: Richard McNaughton. Makeup: Jim Hydes. Set designer: John Elphick. Sound recordist: Peter Davies. Special effects: Peter Neilson, Florenz Fuchs von Nordhoff and Karl-Ludwig Ruppel. Produced by John Croydon & Richard Gordon for Producers Associates & Amalgamated Productions.

Leave a comment