Children help an alien brain with telekinetic powers to sabotage the launch of a nuclear satellite. Jack Arnold’s kiddie-friendly pacifist message film from 1958 is intriguing and fresh in its earnestness, but bogged down by a thin and redundant script. 5/10

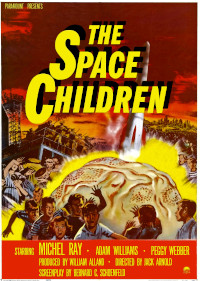

The Space Children. 1958, USA. Directed by Jack Arnold. Written by Bernard Schoenfeld. Inspired by the short story “The Egg” by Tom Filer. Starring: Bud Brewster, Adam Williams, Peggy Webber, Johnny Crawford, Sandy Descher, Johnny Washbrook. Produced by William Alland. IMDb: 4.3/10. Letterboxd. 2.9/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

The Brewsters are en route from San Francisco to a military base along the ragged shoreline of California. Daddy Dave (Adam Williams) is about to join the work on “The Thunderer”, a novel satellite armed with a hydrogen bomb, that is about to be launched. Mommy Anne (Peggy Webber) is wary about starting a new life living in a glorified trailer park along a featureless and wind-swept desert beach. Sons Bud (Michael Ray) and Ken (Johnny Crawford), however, are more interested in the strange noises they hear that their parents can’t, and the weird object being beamed down from the sky into a cave near the base.

So begins The Space Children, a 1958 science fiction melodrama aimed at kids, directed by Jack Arnold and produced by William Alland for Paramount. This thoughtful and atmospheric kiddie flick presented a rare pacifist message in a genre that often set itself up as the standard-bearer for the US military-industrial complex (at least when the films were being made in Hollywood). The film is somewhat overlooked in the ouvre of Jack Arnold, perhaps not entirely without reason.

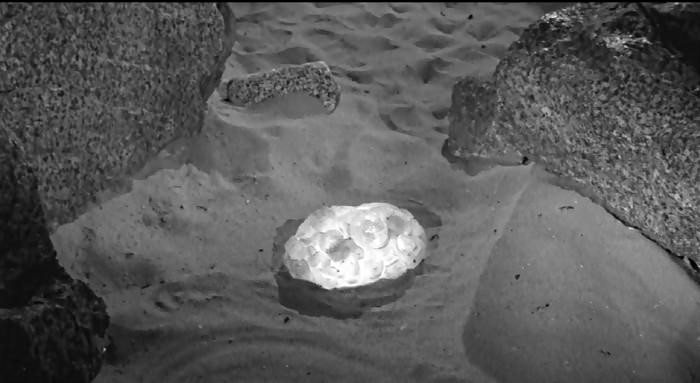

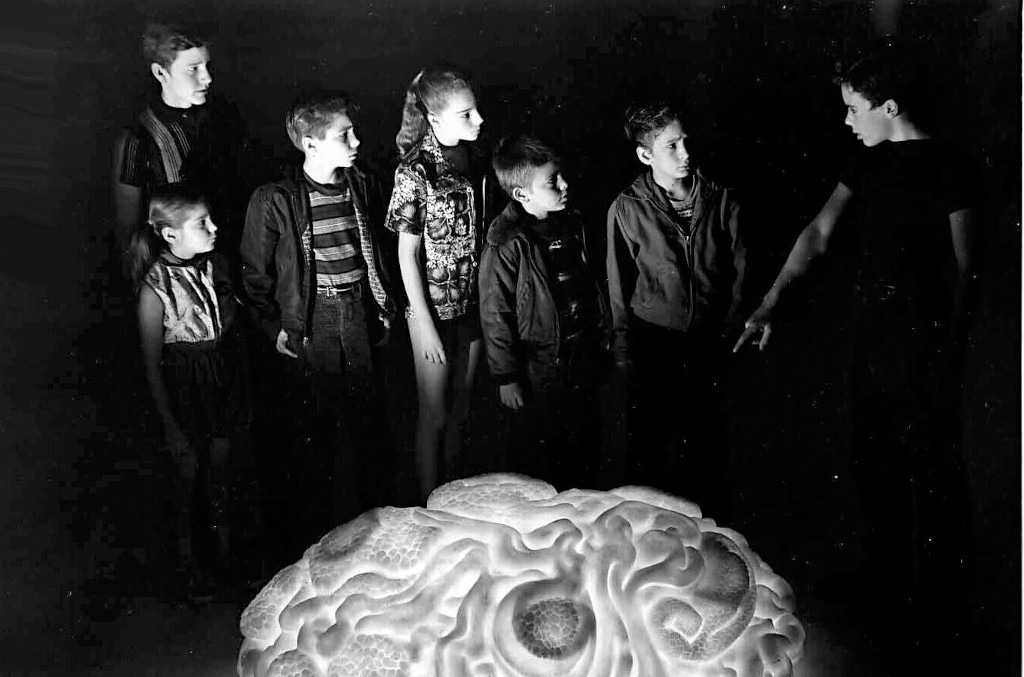

When the family awkwardly settles into their new surroundings, Bud and Ken immediately make friends with the other kids on the block, including Tim (Johnny Washbrook) and Edie (Sandy Descher of Them! fame). In the afore-mentioned cave, the children find a small, pulsating blob of alien ectoplasm, somewhat resembling a brain. While we can’t hear its voice, it is clear that it is communicating with the children, who all nod and apparently agree to what it is saying. Bud is pronounced the leader, and it is made clear that participation in whatever is in store ahead is not optional.

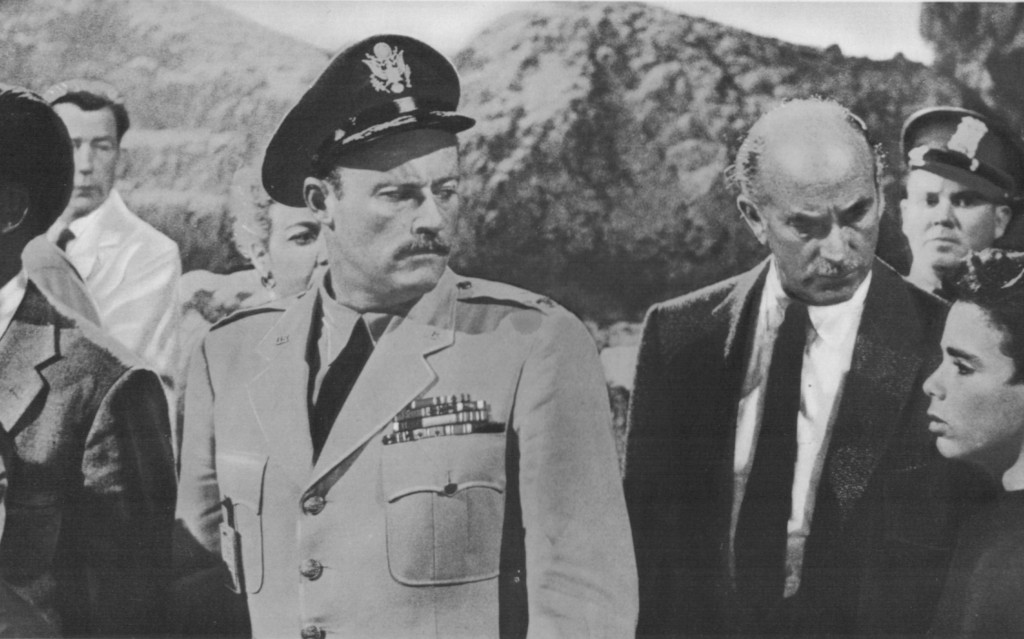

As the story unfolds, we get to visit the launch site and marvel at the six-stage rocket that is going to take the Thunderer into space, and meet some of its personnel. Among the key players are leading scientist, Dr. Wahrman (Raymond Bailey), Lt. Col. Alan Manley (Richard Shannon) and fellow scientists Joe Gamble (SF veteran Russell Johnson) and Hank Johnson (Jackie Coogan, yes THE Jackie Coogan). The plot takes place in roughly equal share along the rocky beach, in the trailer park and on the premises of the launch site and its military research facility. Much of it follows the families settling in to the isolated life at the station, trying to create a sense of normalcy and cameradery, with barbecues, fishing and swimming, all while they are working on a potential doomsday machine. They all go out of their way to convince themselves that they are working for peace and a better tomorrow, but beneath the facade there is an oppressive atmosphere of gloom, as all involved are very well aware that they are contributing to an arms race that may well result in the destruction of humanity itself.

Around one thid into the film, Bud, Ken and the kids take daddy Dave to see the thing in the cave during the night. When Tim tries to leave his family’s trailer, he is stopped by his drunk stepdad, Hank, but shoves him, resulting in a chase across the beach. When they both arrive, Hank catches Tim and is about to beat the living daylights out of him, but the Thing won’t let him harm any of the kids, and kills Hank. Bud and Ken take the Thing home to their parents, scaring the wits out of their mother and prompting their father to say he is going reveal it to his superiors. In a rather spooky moment, Bud stops his father with a touch of his hand, making it clear that the Thing exorts some kind of mind control through the children. As the parents ask the boys what the Thing wants, the boys say they can’t answer, “not until tomorrow night”. As daddy Dave goes to work the next morning, he is informed that the Thunderer is about to be launched in the evening, and puts two and two together. But when he tries to reveal the children’s secret, Bud and Ken show up at the base, and cause Dave to go mute and collapse.

Meanwhile, the children – or the Thing through the children – use their newfound telekinetic powers to disturb the preparations for the rocket launch. Bud makes a fuel truck skid off the road and two other kids make the phone lines go dead. Dr. Wahrman notes that at all incidents, kids have been present, and when he sees them use their powers to pass a sentry and unlock a gate with their minds, he realises something is up. Speaking to Dave, he is able to gain some idea about what is going on through yes and no questions, as he realises that Dave is unable to speak freely about what he knows. Nevertheless, he presses on with the launch. When the rocket is about to take off, its nuclear warhead explodes.

Spoilers ahead:

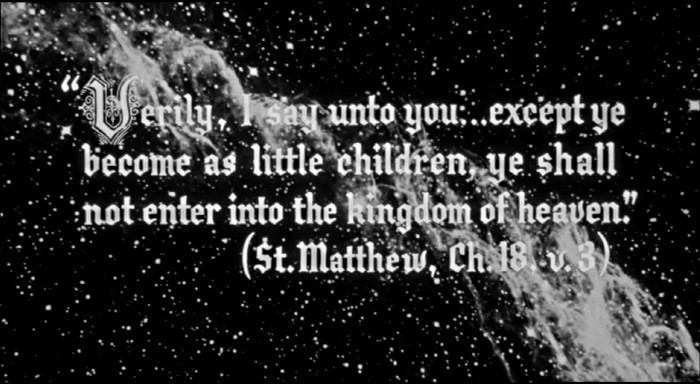

Chasing the children to the cave (to which the Thing has since been returned) they are met by the kids linking arms, creating a wall between the adults and the Thing – which has now grown to ten feet in length. Slowly the Thing emerges from the cave behind the kids. The adults, now furious, demand to know how the children can do such a thing to their parents, to their country, how they can destroy the hopes for peace. Nay, say the children, they have just brought on peace, as there have been similar Things and similar children all over the world, and they have destroyed all nuclear weapons, giving the world a second chance. And behold, there was a light from the heavens, and the Thing ascended to the stars from whence in had come. And there was much rejoicement, and the movie endeth with a Bible quote in fracture: “Verily I say unto you … except ye become as children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven”.

Background & Analysis

Producer William Alland and director Jack Arnold were the kings of science fiction at Universal, reigning supreme in the mid-50s with classics like It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review) and Tarantula (1955, review). Arnold also made The Incredible Shrinking Man (1967, review) for Universal, by many considered his masterpiece. However, diminishing budgets and a lessening interest in the genre from Universal leadership caused both to exit the studio, Arnold in 1955 and Alland in 1957. By 1958 Alland had accepted a financially better offer at Paramount, and Arnold was freelancing. The Space Children, shot in December, 1957, was Alland’s first film for Paramount, and while he himself was better paid his new studio, his budgets were not necessarily bigger, rather the opposite.

The Space Children was loosely based on, or rather inspired by, an unpublished short story by Tom Filer, titled The Egg, that Alland brought to the attention of Paramount. According to film scholar Bill Warren, the original story differed greatly from the finished script by Bernard Schoenfield. AFI writes: “In Filer’s story, Kathy, a young polio victim, finds an alien ‘egg’ after a storm. Mysteriously told to protect the egg for ten hours, Kathy battles against her parents, neighbors and local authorities, who seek to destroy the ever-growing creature. The egg then absorbs Kathy, only to suddenly vanish and leave the young girl cured of her lameness.” Warren writes that the story also involves Kathy’s dog which is at one point engulfed by the egg and a cloud that seems to converse with the egg. According to Warren, the story would have been too slight for a full-length film, had too many overtones of mysticism, and the a sentimental cliché of a crippled girl and her dog, which would have been too sappy even for Hollywood. On the other hand, states Warren, the story is in some ways better than the movie, as the alien’s motives remain a mystery – in the end Kathy reveals that the alien landing on Earth was a mistake, and we never learn why it cured her, and if it did do intentionally. Writes Warren: “For the most part, in The Space Children, the potential for lyrical mystery is replaced by a clunky literalness”.

Warren writes that Alland and Schoenfield sold Paramount on the central premise, that the alien both appealed to and employed the innocence of children in order to carry out its mission on Earth. However Alland noted that the story lacked a central antagonism that was crucial for a movie. In his words, the script would pit humankind’s propensity for destroying itself in a nuclear war (evil) against the innocence and intelligence (good).

Aliens trying to prevent humanity’s forages into space was not a new idea, it had been covered in films like Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review) and War of the Satellites (1958, review). Even older and more widespread was the trope of aliens reacting to humanity’s propensity for killing ourselves with nuclear weapons and spreading the disease of war into the galaxy. German Der Herr vom Anderen Stern (1948, review) was the first movie in which an alien descended upon Earth to spread the message of pacifism, however the grandaddy of these movies was of course The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, review), which seems a major inspiration for The Space Children. Benevolent aliens also turned up in the British knock-off Stranger from Venus (1954, review) and, with some caveats, in the red scare film The 27th Day (1957, review). It Conquered the World (1956, review) and Japanese The Mysterians (1957, review) subverted the trope, with aliens masquerading as the saviours of mankind, only to begin an invasion of the Earth. Plain evil was the The Brain from Planet Arous (1957, review), who targeted America’s new nuclear weapons, setting itself up as the ruler of the world.

The alien’s awesome powers to disrupt technology was also, of course, borrowed from The Day the Earth Stood Still, a feature not present in Tom Filer’s original story. And while its telepathic connection to certain humans was a major plot point in the story, it itself was not new to the movies either, famously turning up in films like It Came from Outer Space and Invaders from Mars (1953, review), among many others.

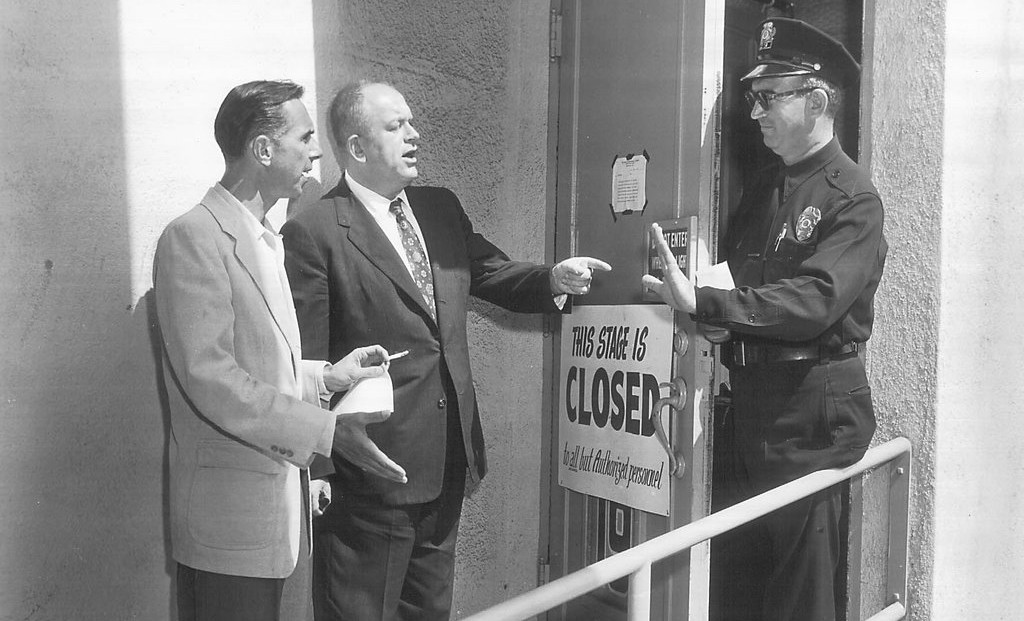

The Space Children was made on a modest budget, as evidenced by the sparing use of sets and extensive location shooting. Much of the film is shot on Leo Carrillo State Beach just north of Malibu, and most of the rest of the movie on cheap sets at Paramount studios. The film had a setback just days before filming, when the actress that was cast as Anne Brewster backed out of the role. William Alland contacted his old friend Orson Welles and asked him if he knew an actress who would fit the part and who would be able to get into character quickly. Welles suggested Peggy Webber, whom he had worked with on Macbeth in 1948. It turned out to be a good choice. Webber is one of the best actors in the film, giving a believable performance of the caring mother who looks upon the prospect of living on an isolated military research site for the overseeable future. As opposed to many Hollywood damsels playing these kind of roles, Webber comes across as everyday and real, in the best possible sense, and also gives a strong performance.

Some of the best moments in the movie are the short conversations between the women in the trailer park – all there because their husbands have been called in to “ensure lasting peace” by creating a monstrous machine of death. Between the women there is created a kind of unspoken cameraderie of unease, that shows between the cracks in the peppy words they speak to each other over laundry and barbecues.

Like in most of his SF movies, Jack Arnold uses the surroundings to create an atmosphere of mystery and foreboding. Arnold shoots the far-stretched coastline in vey much the same way as he shoots his deserts, as unchanging, eternal landscapes in which humans are but passing shadows. Arnold said in interviews that he wanted uncluttered landscapes on which to let the stories unfold. In his direction, the beaches, oceans and deserts gain a poetic nature, much like the cinematic equivalent of Ray Bradbury’s literature. It seems like fate that the first science fiction movie he made, It Came from Outer Space, was scripted by Bradbury.

Like The Space Children, It Came from Outer Space was a Message film, albeit less overtly so that the latter picture. The Space Children wears its message on its sleeve. Arnold had a tendency, when nudged by the script, to give his movies’ finales Biblical Importance, using religious imagery that tended to lend some of his films a melodramatic punch, occasionally verging on the pathetic. In some instances this worked well, as in The Incredible Shrinking Man, where he had Richard Matheson’s fantastic script to weave his religious imagery into. Alas, in The Space Children he doesn’t have Matheson’s words, and the ending of the movie unfortunately comes across as pretentious, complete with the alien ascending to the heavens amidst a halo of light, and the movie ending with a Bible verse. It is all a bit too thick to swallow.

Nevertheless, despite the bombastic finale, The Space Children is nowhere near as bad as its reputation was back in the day. The film is one of a substantial group of pictures whose reputations have been needlessly sullied by their inclusion in the rifftrax TV show Mystery Science Theatre 3000 (MST3K). Back in the day, IMDb:s audience rating for The Space Children was as low as 1.9/10, a rating reserved for such awfulness as Manos: The Hands of Fate (1966), Disaster Movie (2008), and Birdemic: Shock and Terror (2010). In subsequent years, the film has undergone a reevaluation by audiences that are not primarily acquainted with it through the MST3K riffing, and as of writing in 2024, its IMDb score sits at 4.3/10. This is still a low rating, considering, for example, that all of Bela Lugosi’s infamous Monogram 9 films have a higher audience score than this.

The Space Children does have a lot going for it. First and foremost, it has Jack Arnold, arguably the best science fiction director of the 50s. This is by no means Arnold’s greatest work – he is hampered by a low budget and a less-than-terrific script. But Arnold is able to infuse even the most mundane situations with his low-key visual poetry. As is often the case, The Space Children is most effective in its still and contemplative, often enigmatic moments. While not necessarily an actors’ director, Arnold aways shot people beautifully, with immaculate framing and lighting, letting the environment and background speak for the characters’ emotions and thoughts, or juxtaposing actions against the backgrounds. He was at his best when letting his themes seep through the visuals of the film, rather than formulating them in words. Unfortunately, these moments are far fewer in The Space Children than in films like It Came from Outer Space or Creature from the Black Lagoon. Apart from the widestretched, ragged beaches, Arnold doesn’t have much to work with in terms of visuals, and much of the story takes place in nondescript rooms and cramped trailers, robbing the director of his most powerful tool.

But instead, he uses the faces of the children to good effect. Evil children are always effective on film, and even though the kids in this film are not evil, they carry through sabotage and threats, be it for the greater good, with a sense of silent and enigmatic satisfaction. The scenes in which the children stand motionless, watching silently when trucks veer off the road and telephone lines go dead, are among the most striking in the film.

The greatest detriment to the film is its script. And while this also has its highlights, mostly in between dialogue and thanks to the conteplation of its themes, it often comes dangerously close to tipping over into silliness, and above all, treats its themes with a sort of naive, clunky pathos.

One theme in The Space Children, which is often present in sci-fi and fantasy films inhabited by children, is the generational gulf between grown-ups and kids. The children, unsullied by politics, propaganda, careerism, selfishness and ideology, are often presented as pure and good, instinctively reaching for the altruistic and naive in a world determined by self interest (personal, national, ideological), in contrast with their grown-up counterparts. Usually, in better films exploring this theme, we focus on a grown-up who takes a personal journey towards becoming a better human being by rediscovering the childlike innocense in himself. The Space Children veers towards this in the character of Dr. Wahrman, but he gets far too little screentime in order for his journey to be effective (and, more importantly, he never reaches the end of said journey).

Ultimately, the above is not the main theme of the movie, which is a warning against nuclear proliferation and a case for altruistic pacifism among mankind. William Alland said in an interview that if he had had a bigger budget, the ending would have shown nuclear warheads all over the world destroyed by aliens, and children celebrating in different countries. This theme is made all too clear at the end of the movie, with the hi-falutin’ speech given by Bud Brewster. As a fable, the film carries an earnest and endearing conclusion, but it is preachy and comes at the expense of functioning drama and a more serious geopolitical discussion. It also carries with it the major flaw that dampens the enthusiasm of the conclusion of The Day the Earth Stood Still: humanity saves itself from nuclear annihilation not because we have grown any wiser, but because we are stopped by an alien intelligence. In The Space Children, humanity shows no signs of redeeming itself, and the scientists in the movie would probably be ordered by the government to build another nuclear satellite, unless the aliens vow to return to destroy it, which they don’t.

However, as my 10/10 star review of The Day the Earth Stood Still demonstrates, even a somewhat flawed conclusion as this can very well be supported by a good script. Unfortunately, the script for The Space Children doesn’t hold up. It is awkwardly structured and repetitive. It feels as if Alland and screenwriter Bernard Schoenfeld have an idea for a premise and a conclusion, but not for much in between. The alien lands, the children (unsuccessfully) sabotage the launch, and the alien destroys the warhead. All drama in between is essentially moot. Dr. Wahrman sees the alien’s and the children’s point, but goes ahead with the launch anyway. Father Dave Brewster seems somewhat sympathetic but is ultimately forced by the alien to do its bidding. The women are uneasy about the whole project, but they ultimately have no impact whatsoever on the plot. Nobody goes on a journey here and no hearts and minds are changed. The alien is never challenged, nor does it seem to learn anything as Klaatu does in The Day the Earth Stood Still. The actions of the children don’t really contribute to anything. Yes, they keep the alien safe, in a way, but it seems perfectly capable of taking care of itself, as highlighted by its murder of Joe Gamble. No grown-ups notice its landing in a cave, and none of them would have caught on to it if it wasn’t for the children. The children don’t help in preventing the launch in any way – despite all their sabotage, the launch proceeds as planned, until the alien blows the warhead. Everything in the films speaks to the conclusion that it could have just sat in its cave and waited for the opportune moment to act, all without the the help of the kids, rendering the entire plot kind of moot.

The film has its staunch defenders, who come up with elaborate explanations for everything that we mugglers see as wrong with the script, very much like Star Wars fans bending over backwards to explain why the duel between Vader and Kenobi in Star Wars: A New Hope was so slow and clumsy compared to the prequels. And this is all well and good: coming up with a mythology of our own in regards to our favourite film is something we all do to fill in the gaps and make sense out of the inevitable plot hole or inconsistency. But for those of us who are not passionate about explaining away every weakness of the script, these plot holes and inconsistencies remain.

These inconsistencies are not only detrimental for the content of the film, but also for its pace and plotting. As nothing anything does in the film has any real impact on the end result, screenwriter Schoenfeld and director Arnold scramble to meet the film’s 70-minute running time. An unproportionate amount of time is spent running up and down the beach from one location to another. At one point it – for reasons never explained – becomes crucial to move the alien from the cave to the Brewsters’ trailer, only for it to be taken back to the cave again the next morning. This kills at least ten minutes of runtime, but serves no story purpose. The kids visit the cave at several occasions, and towards the end Dr. Wahrman also pays the alien a visit – but again, with no consequence for the story, as he continues with the satellite launch regardless.

We haven’t yet said much about the alien itself. In fact, we don’t even know if it really is an alien – the ending suggests that it might actually be an angel, and its exact nature is probably left ambiguous on purpose. But for the sake of simplicity, we’ll call it an alien. The fully grown alien was around 10 feet (3+ meters) long and seemingly made from some sort of plastic/rubber material. It was designed and created by special effects artist Ivyl Burks, and had an elaborate air-pressure mechanism to make it “bubble”. It was also outfitted with over $3000 worth of neon lights. Technically it is an impressive build, and it looks good, much better, in fact, than a lot of “monsters” in A-budget movies. On the other hand, it is not particularly ambitious nor original. While the nature of the thing is never explained, it does look a lot like a pulsating brain – and even the trade press at the time of the film’s release thought that the alien brain was becoming old hat.

One point of contention over the years has been the relationship between the kids and the alien. Some have seen the alien as controlling the children, making them do its bidding. As Glenn Erickson points out: “The kids seem happy, yet are compelled to obey the brain’s orders. No dissent is allowed. The little gang of conspirators maintains constant telepathic contact with each other, much like John Wyndham’s menacing “Midwich Cuckoos” children of Village of the Damned. Whatever the purpose, surrendering one’s psychological liberty to an alien entity doesn’t sound good to these ears.” This, of course, would put a significantly bleaker slant on the story. However, the script seems to go out of its way to make it clear that the children act out of their own volition, at least to a certain extent. There is one scene, however, that adds to the confusion, and that is one in which the oldest of the kids tries to smash the still “infant” alien with a rock, and is stopped by the alien’s powers, after which he is basically told by Bud Brewster to step back in line and follow orders. However it seems clear that the orders he is meant to follow are Bud’s and not the alien’s, even though it seems like the alien has promoted Bud as the leader of his tiny army of rebels. My interpretation is that there is a good argument to be made that the children do act out of their own volition, and have the power to pull out if they wish to, but to what extent the alien is manipulating them on a purely suggestive level is unclear. We don’t know what it is communicating to them: is it arguments, pleas or orders? Is it a two-way communication? It does not seem so, the alien seems to be telling them what to do, rather than having conversations. Whatever the case, it does not seem wholly benign. It is a flaw of the script that the relationship is never made clear.

The acting, as stated, is for the most part good. The casting is interesting inasmuch as most of the actors are ordinary-looking, which adds to the realism of the movie. There is no glamour girl in short skirts to spice up proceedings – partly, one supposes, because the film was aimed at children. The child actors are a mixed bunch, but the three main characters – the Brewster brothers and Eadie Johnson – are all played by actors who refrain from overacting in the manner that was so typical for child actors in the 50s, and indeed to this day: Michel Ray, Johnny Crawford and Sandy Descher. Ray in particular impresses with his restrained and moody performance, aided by a natural beaty and large eyes, which helped him land the role as one of the young fighters who join Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia. Descher, of course, had impressed mightily in Them! (1954, review). She is not quite as outstanding in The Space Children, but then again the script doesn’t allow her too, either. Peggy Webber as the Brewster mother, as stated, outstanding, and Adam Williams as the father, playing an unusually sympathetic role, comes through with flying colours. Russell Johnson, usually an actor who played more sympathetic roles competently, in numerous science fiction movies as well, fares less good in the role as the boozing, obnoxious father in the camp, partly because his role is badly written. Former child star Jackie Coogan, now in his 50s, seems to be in the film to provide some levity, and his role is redundant. Richard Shannon and Raymond Bailey, playing the military and the scientific authorities, respectively, are solid.

The Space Children has its flaws, flaws that ultimately relegate it to a footnote it the history of science fiction movies. It is hampered by an odd lack of stakes. We know the children are not going to get hurt, because children never got hurt in children’s films in the 50s, and we also know that the alien probably can’t be hurt, because that was one of those weird things in 50s science fiction films: aliens were (almost) always invulnerable. And the script isn’t able to work up much emotional interest in whether the satellite will be launched or not, it’s really just a MacGuffin. So what’s left is really more of a mystery play – who is the alien, what does it want, what are it and the children planning? But this angle is pretty quickly played out, and this is where the personal drama should kick in. But, as stated, there are no character journeys to take part of in this film, which is perhaps its biggest flaw. However, despite its weaknesses, The Space Children is a movie well worth a look. It builds up a contemplative, somber atmosphere and as a study of the mindsets of the 50s cold war it is exquisite. Arnold’s poetic direction and the above average acting for a B-movie help make the film gripping enough to overcome the scripting flaws, and while badly put together, the script has many interesting ideas and dialogue that was quite progressive for its time.

Reception & Legacy

The Space Children premiered in June, 1958, on a double bill with producer William Alland’s The Colossus of New York (review). However, according to Bill Warren, in many areas it played as the B-feature to Jerry Lewis‘ Rockabye Baby. I haven’t seen box office numbers, but with such a slight budget, it probably made its money back.

As the Internet Archive is currently down, I can’t access most of my usual sources for historical reviews. However, it seems that The Space Children was fairly well received by critics. British Film Bulletin said “This moral tale achieves some success as a science fiction essay for children and, […] it is convincingly presented”. Jack Moffitt at the Hollywood Reporter called it “a distinguished little picture” that “adds the new element of tenderdness to science fiction films”.

In Variety, Gilb wrote: “While there’s nothing pretentious about Children, its science-fiction aspect has a topical slant that may serve to lure adult action fans. But basically this is a crack, suspense thriller for the Saturday matinee trade. With a flock of moppet thespers on the screen the kids in the audience will have no difficulty in achieving a sense of personal identification.”

In later reviews, The Space Children has at least one staunch defender in John Baxter, a man who in 1970 wrote a book called Science Fiction in the Cinema in 1970, despite seeming to have little love for science fiction in the cinema. Baxter did, however, like Jack Arnold, and had a fondness for the “pale, grey and melancholy” atmosphere of The Space Children. Baxter calls the movie “Arnold’s summation, exploring the conflicts implicit in the confrontation between man and the forces of another, alien world, in this case that of childhood”. He continues: “Restrained and thoughtful, The Space Children contains the best of Arnold’s mature work”.

DVD Savant Glenn Erickson writes: “A matinee favorite for its completely unexpected anti-militarist theme, The Space Children is an engaging but thoroughly confused bit of liberal message filmmaking.” Richard Scheib at Moria also likes the film, giving it a respectable 3/5 star rating: “The Space Children is a modestly enjoyable, if minor entry from Arnold. It is certainly the most overlooked film in Jack Arnold’s oeuvre […] In most regards, The Space Children is a perfect little 1950s B-picture. For all that it attempts, the film achieves it with modesty. The performances from the kids, which include a young Jackie Coogan among their number, are not too bad.” (Scheib must have been a bit distracted when he wrote his review, I’m sure he was aware Jackie Coogan was in his 40s when this film was produced and not a kid.)

The Space Children seems to have been somewhat forgotten after its release, and from what I have gather from my sources, wasn’t a fixture on TV, as many of the 50s movies were. It also took a very long time to get a home video release, and for ages the only copies of it around were bootleg VHS tapes recorded from TV airings. Thus, the film film didn’t have much of a following when it turned up on MST3K.

Cast & Crew

Between 1953 and 1957, Jack Arnold had directed, basically, all of Universal’s most successful science fiction films of the 50’s in the ridiculously short time-span of three years. Before that he had primarily been known as a competent documentary filmmaker – he produced and directed several films for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, including the docudrama With These Hands (1950), which received an Oscar nod.

Amazingly, the classic It Came from Outer Space (1953, review) was only his second feature film, a surprise hit in 3-D that gave Arnold the chance to update Universal’s classic monster roster with The Creature from Black Lagoon (1954, review) and the inferior sequel Revenge of the Creature (1955, review). He did some uncredited directing on the costly This Island Earth (1955, review) and followed up with the B-movie classic Tarantula (1955, review).

Arnold was an anomaly among science fiction directors in Hollywood inasmuch that he was a science fiction fan himself. Thus, he understood that SF was not only juvenile escapism fuelled by flying saucers and giant monsters, but about ideas.

He exited Universal in 1955, partly because he grew frustrated at the studio’s unwillingness to take science fiction seriously, although he did return on occasion, as evidenced by The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), which he did for Universal on a freelance basis. Unfortunately, by the late 50’s science fiction was being viewed as being good for little else than exploitation cash-grab by most studios, partly thanks to the success the low-budget schlock films of Roger Corman over at American International Pictures, which meant that Arnold was offered few possibilities to make the kind of films he wanted to make. His frequent producing partner William Alland had moved to Paramount in 1957, and called on Arnold to direct the intriguing but flawed pacifist message film The Space Children in 1958 on a shoestring budget. His last American SF film of the 50’s, and for a long time to come, was Universal’s Monster on the Campus (1958, review), a trivial re-tread of 1953’s The Neanderthal Man (review).

Arnold then made the well-regarded western No Name on the Bullet for Universal, after which he had enough of Hollywood for a while and instead teamed up with Peter Sellers in the UK, to shoot The Mouse that Roars, a cold war comedy satirising US foreign policy. Co-produced by Columbia, it became a critical and commercial success in the US, and introduced Sellers, here in his first solo starring role, to an American audience. However, the film didn’t necessarily lead to a lot of bigger and better things for Arnold. For a while, he was pegged as a comedy director, a genre that simply wasn’t his forte. In the early 60’s he directed two moderately successful Bob Hope comedies, and in 1969 returned to sci-fi at Paramount, along with another genre veteran, Ivan Tors, for the underwater comedy Hello Down There. He and former gill-man Ricou Browning, here as assistant director, were hired for their underwater work with the Creature series. However, in the 60’s Arnold largely transitioned into TV, where he had a decent career as a journeyman director, including longer stretches at shows like Gilligan’s Island and The Love Boat, as well as occasional SF shows. His movie career dwindled, and in the 70’s his output co nsisted exclusively of softporn romps and a couple of Fred Williamson blacksploitation films. Arnold retired in 1984 and passed away in 1992.

Actor-turned-producer William Alland started his career as a member of Orson Welles’ legendary stage and radio theatre company Mercury Theatre. Among other things, he was part of the famous production of The War of the Worlds in 1938. As an actor he is probably best known for playing the newspaper reporter who ”narrates” Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941).

Alland quickly moved up in his career, started producing radio shows and in the early fifties he joined Universal Studios as a movie producer. In 1953 the studio assigned Alland to produce a low-budget SF film in order to cash in on the 3D craze. The result was It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), which became one of the biggest grossers of the year for Universal, and is considered a genuine classic of the era today. It also brought together Alland and director Jack Arnold, who became the dynamic duo of science fiction at Universal during the mid-fifties. Eager to follow up on the success of It Came from Outer Space, the studio commissioned another 3D sci-fi from Alland and Arnold, but Alland, which became Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), an even bigger success and considered a bona fide classic. The movie spawned two sequels, both of inferior quality, Revenge of the Creature (1955, review) and The Creature Walks Among Us (1956, review). The latter was hampered by the semi-flop of Alland’s costly SF epic This Island Earth (1955), which led Universal to start slashing its SF budgets. The effects of the slashing are on full display in the studio’s following Alland-produced science fiction films, The Mole People (1956), The Deadly Mantis (1957) and especially in The Land Unknown (1957, review).

Disparaged at the situation at Universal, Alland moved to Paramount, where he produced two low-budget SF pictures, The Space Children and The Colossus of New York. While flawed, both are considerably more interesting than his last three SF clunkers for Universal. In between SF assignments, Alland also produced more “conventional” films, primarily westerns. In 1961 he tried his hand at directing a teen flick with Paul Anka in the lead, with dubious results. He produced a couple more films before leaving the film business in 1966. According to a Los Angeles Times obit, he then started developing and manufacturing sail boats, and during the last 10 years of his life worked part-time for the Los Angeles Times Poll. Alland was one of the informants for the House Un-American Activities Committee, acknowledgeing his past as a member of the Communist Party and naming other members, many of whom were blacklisted, among them screenwriter Bernard Gordon, who worked on Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, review) and The Man Who Turned to Stone (1957, review). Alland passed away in 1997.

Of the child actresses in the leading roles, Sandy Descher is probably best known to genre fans, thanks to her haunting part in Them! (1954). Descher became something of a minor celebrity in her following career, after appearing in films like The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954), 3 Ring Circus (1954) and The Prodigal (1955). She got an even wider audience in her late teens when she landed a steady role on The New Loretta Young Show (1962-1963), after years of doing small parts in different TV series. However, as she got older her roles started getting sparser, and she dropped out of acting at 21. Descher was one of those ”bratty” child actors that Hollywood seems to love, and the audience often hates, and judging from her interview, she seemed to clash a bit with her co-stars, what I’m reading between the lines is a juvenile case of inflated ego, but I could be misinterpreting things. But she also had a bit of a rough time with death threats and stalkers, as many child stars do.

Picturesque and serious, Michel Ray was set on a good career path after being cast in a 1954 movie thanks to his skiing talents. He had roles in around half a dozen pictures and as many TV shows, until the film he is best remembered for, as the young gay fighter Farraj who befriends Peter O’Toole in Lawrence of Arabia (1962). However, soon after this role, Ray dropped out of acting to pursue his business studies, and later became a billionaire. He also represented Great Britain in three winter olympics in both ski and luge.

Singer, composer and actor Johnny Crawford is the child actor with most name recognition here, as one of the original Mouseketeers in The Mickey Mouse Club in 1955, and went on to star as the lead character’s son in the successful western series The Rifleman (1958-1963), a role which earned him an Emmy nomination. His popularity earned him a recording contract in the early 60s, and between 1962 and 1963 he had four Top 40 singles, including “Cindy’s Birthday”. Crawford was typecast in western TV series, and as a teen pop idol during the 60s, but after this, his career dwindled, although he continued acting semi-regularly throughout the 70s, 80 and 90s, and in the 90s founded a popular vintage dance orchestra. He retired from acting in 1999, bade did a one-film comeback of sorts in the lead of the 2019 in the low-budget western meta film Bill Tilghman and the Outlaws. He passed away in 2021. He appeared in the SF movies The Space Children (1958), Village of the Giants (1965) and The Thirteenth Floor (1999).

Adam Williams, real name Adam Berg, entered the movie business at the age of 29 in 1951, and gained some recognition when he scored the lead in the 1952 crime movie Without Warning!, where he played a serial killer. The role pidgeon-holed him as a heavy, and he spent much of the 50s playing henchmen. He played a car bomber in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) and a Nazi officer in The Rack (1956), opposite Paul Newman. In between movies he often appeared on TV, including an episode of Science Fiction Theatre in 1955. He did another rare co-lead in Jack Arnold’s kiddie science fiction film The Space Children (1958), playing the father of two boys discovering a telepathic, pacifist alien brain outside a nuclear rocket research facility. The next year, he played the role he is probably best remembered for, that of James Mason’s henchman in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest.

During the 60s and 70s, Williams mainly worked as a guest star on TV, occasionally playing minor roles in movies, such as Robert Aldrich’s The Last Sunset (1961) and the family drama Follow Me, Boys! (1966). He also had a small role in the TV movie Helter Skelter (1976), which, or course, followed the Charles Manson investigation. Genre fans may know Williams from two episodes of The Twilight Zone, including the legendary “The Hitch-Hiker”, in which is plays the sailor picked up by the lead character. Williams retired from acting in 1978.

Peggy Webber was (is) a much-respected radio and stage actress, writer and director, who occasionally dabbled in film and TV acting as well. Born in 1925, she started doing half-time performances in movie theatres at the age two, and made her radio debut at age 11. By the time she was 20, she was already writing, directing and acting on stage, in the radio and on TV. During her career she did thousands of plays and episodes for radio, probably best known for her work on Dragnet, for which she did numerous characters – her work also spilled over on TV when the show became televised in the early 50s. In the 50s, Webber co-founded an acting school, or “workshop” in Los Angeles, and in the 80s co-founded the hugely successful radio theatre CART, for which she produced, wrote, directed and sometimes appeared in numerous award-winning radio plays. In 1949, Peggy Webber was nominated for the very first Primetime Emmy Award for best TV show, as producer of the program Treasures of Literature In 1950 she wrote and directed the very first episode of The Colgate Comedy Hour on TV. In 2014 whe became the first woman to receive the Norman Corwin lifetime acheivement award for audio theatre.

As a film and TV actress, Webber’s career credits are not particularly impressive, and mostly consists of supporting roles in movies and guest spots on TV shows. She is probably best known for appearing as Lady Macduff in Orson Welles’ Macbeth (1948), in a bit part in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956), and for playing the female co-lead in Jack Arnold’s The Space Children (1958) and the lead in Alex Nicol’s directorial debut The Screaming Skull (1958).

Jackie Coogan, of course, is known for three things: upstaging Charlie Chaplin in The Kid (1921), getting swindled of all his earnings as a hugely popular child actor by his mother, and playing Uncle Fester in the TV show The Addams Family (1964-1966). Coogan, born 1914, came from a family of actors and was discovered by Chaplin in 1919, and in 1921 became global phenomenon in The Kid, going on to play Oliver Twist in 1922, and followed up his success with several hit films for most major studios during the silent era and the early talkies. His career dwindled when he reached maturity, and tragedy struck in 1935, when his father died in a car crash. His earnings from his films passed to his estranged mother and step-father, and when he was to take control of his assets, he found that his mother and step-father had squandered nearly all of it on their luxury lifestyle. Coogan had not only earned money from his films, but also from merchandising deals set up by his father. His total earnings were estimated to $4 million, the equivalent of nearly $90 million in todays money. His mother refused to give him even the remaining money, as she claimed no contract had ever been set up guaranteeing him any earnings from Jackie Coogan Productions. Coogan sued his mother and the court ordered her to give up half of the remaining assets to Jackie. However, after legal feels, he only received around $125,000. Granted, this is nearly $3 million in today’s money, so he wasn’t exactly broke.

Coogan continued acting up until the early 40s, when he went off to serve in WWII, and when he returned, he found his name carried little star power any longer, and he wound up making a living in Monogram movies, program westerns and other cheapo fare, like the infamous SF clunker Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review), one of the worst films we have reviewed on Scifist. He was, however, steadily employed in B-movies and TV shows, and regained some of his fame of old as the lively character of Uncle Fester in the hit show The Addams Family (1964-1966). He kept on acting until his death in 1984. Mesa of Lost Women and The Space Children (1958) were his only science fiction movies.

Russell Johnson’s talents are wasted as the abusive drunkard in The Space Children, because of the badly written character. Johnson had an everyman charisma, good looks and some serious acting chops, which were all on display after he was picked up by Universal soon after his film debut in 1952. He appeared to his advantage in the SF movies It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), as one of the body-snatched telephone linemen, and This Island Earth (1955, review), as Rex Reason’s confidante at the mysterious mansion. Realising that Universal was grooming a new cohort of leading men, and he was rather low on the list, he left the studio, and continued as a freelancer, primarily in low-budget movies and TV. He appeared as the hero in Roger Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957, review), The Space Children in 1958, and a number of sci-fi TV series, including The Twilight Zone (1960-61), The Outer Limits (1964), and Wonder Woman (1978). He revealed in a later interview that he had wanted to appear in the original Star Trek series, but was never cast. He will always be best remembered, however, for playing the Professor in the beloved TV series Gilligan’s Island (1964-1967), and its numerous film adaptations and spinoffs, including the slightly less loved sci-fi series Gilligan’s Planet (1982).

Raymond Bailey plays plays the kind-hearted lead scientist in The Space Children. Bailey was another actor who would make his biggest impression on TV, in the recurring role as tight-fisted banker Milburn Drysdale in the principal cast of The Beverly Hillbillies (1962-1971). Bailey also had bit parts or supperting roles in the SF films S.O.S. Tidal Wave (1939), alongside Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi in Black Friday (1940, review), Tarantula (1955, review), The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957, review), The Absent Minded Professor (1961), Irwin Allen’s Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962) and Disney’s The Strongest Man in the World (1975), starring Kurt Russell. He appeared in several SF anthology shows, including three episodes of The Twilight Zone.

One of the military men in The Space Children (1958) is played by Larry Pennell, who would also later secure a recurring role on The Beverly Hillbillies. Pennell appeared in numerous SF TV shows as a guest star, including Land of the Giants, Quantum Leap and Firefly. He also appeared in the science fiction films City Beneath the Sea (TV, 1971), Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn (1983), The Borrower (1991) and the straight-to-video movie Prehysteria! 2 (1994).

Peter Baldwin, playing a security officer in The Space Children (1958) was a contract player at Paramout, who seemed to have a successful future ahead of him after appearing in a number of pictures, including Stalag 17, in the early 50s. However, his career stalled in the mid-50s, and he was loaned out to TV between minor supporting roles, mainly in B-movies for Paramount, including a substantial part in I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958, review). In the early 60s he followed a number of other struggling American actors to Italy, where he became a minor star in films like the horror movie The Ghost (1963) and crime dramas The Possessed (1965) and The Mattei Case (1972). However, he had a more successful career as a TV director from the mid-60s onward, directing over 100 TV shows or TV movies between 1964 and 2002, and got an Emmy in the 80s. These included 15 episodes of the kiddie show Small Wonder (1985-1989) about a suburban family with a robot designed to look like a little girl.

The Space Children was the film debut of Orison Whipple Hungerford, billed as Ty Hungerford. A square-jawed former college footballer, he would later change his name to Ty Hardin, became a TV star and an international movie star, made his way through eight wives, was jailed in Spain for drug smuggling and once noted: “I’m really a very humble man. Not a day goes by that I don’t thank God for my looks, my stature and my talent.”

Hardin was noted by a talent scout in 1957 when at a costume party dressed up as a cowboy. He was put under contract at Paramount and had small roles in films like The Space Children and I Married a Monster from Outer Space in 1958, but had a hard time getting his foot through the door. However, the same year, he moved to Warner, who put him on TV, where he created a stir as Bronco Layne in the western series Cheyenne. So popular was his character that Hungerford, now going by the moniker Ty Hardin, got his own show, Bronco (1958-1962), which became a global hit. After co-starring in a handful of fairly well-regarded B-pictures for Warner in the early 60s, Hardin also thought he’d try his luck in Europe, where Bronco was also popular, and went on to star in a number of films, primarily in Spain and Italy, including Savage Pampas (1965) and Acquasanta Joe (1971). He had small roles in Hollywood films made in Europe, such as Battle of the Bulge (1965) and Billy Wilder’s Avanti! (1972), and starred in the horror movie Berserk (1967), opposite Joan Crawford, which was filmed in the UK. In 1969 he starred in the Australian TV show Riptide, which ran for one season. After his run-in with the law in Spain in 1974, Ty Hardin returned to the US, where he mainly played small roles in low-budget movies or had guest spots on TV. In 1981 he appeared in the low-budget fundamentalist Christian apocalypse film Image of the Beast, in which the mark of the beast has been digitized.

Janne Wass

The Space Children. 1958, USA. Directed by Jack Arnold. Written by Bernard Schoenfeld. Inspired by the short story “The Egg” by Tom Filer. Starring: Bud Brewster, Adam Williams, Peggy Webber, Johnny Crawford, Sandy Descher, Johnny Washbrook, Russell Johnson, Raymond Bailey, Richard Shannon, Jackie Coogan, Eilene Janssen, Jean Engstrom, Vera Marshe, Larry Pennell, Peter Baldwin, Ty Hardin, David Blair. Music: Van Cleave. Cinematography: Ernest Laszlo. Editing: Terry Morse. Art direction: Hal Pereira, Roland Anderson. Makeup supervisor: Wally Westmore. Sound editor: Ray Alba. Visual effects: Farciot Edouart, John P. Fulton. Produced by William Alland for Paramount.

Leave a comment