Roger Corman’s 1957 monster movie is quintessential SF schlock. As a scientists are picked off one by one by telepathic giant crabs, an inventive script and lightning pace compensate for the shortcomings of the production values. 6/10

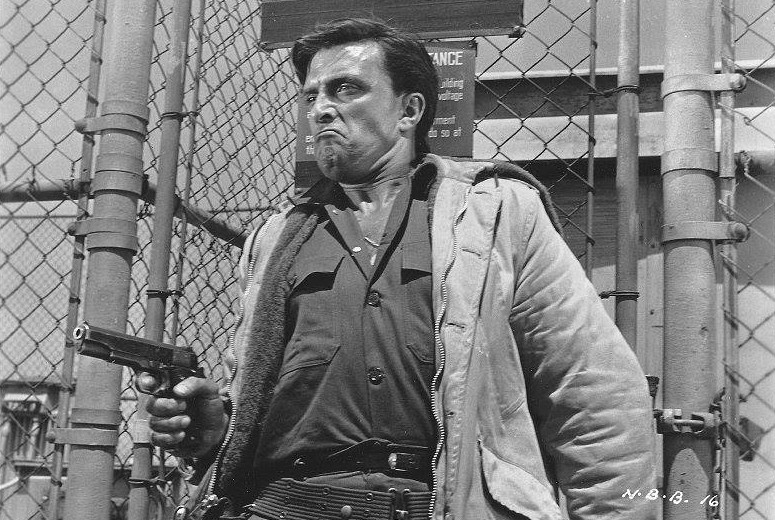

Attack of the Crab Monsters. 1957, USA. Directed by Roger Corman. Written by Charles Griffith. Starring: Richard Garland, Pamela Duncan, Russell Johnson, Leslie Bradley, Mel Welles, Ed Nelson. Produced for Allied Artists.

A group of scientists arrive at a remote island to study the effects of fallout from nuclear testing on plants and animals. They are replacing the previous team, which has gone mysteriously missing, leaving behind nothing, “not even fingernail clippings”, other than an abruptly ending journal reporting strange findings. This time, the team is accompanied by a small group of navy boys, but things start badly, as we are hardly five minutes into the film before the first navy man (screenwriter Charles Griffith) falls into the sea and is mysteriously decapitated.

Strange phenomena start occurring. Huge sinkholes appear overnight, and soon the navy lads report that the entire island is sinking. Biologist Martha Hunter (Pamela Duncan) and Dr. Carson (Richard Cutting) are awakened in the middle of the night by the voice of the dead leader of the previous expedition, who calls them to the sinkhole. Carson climbs in, but falls and screams in agony. The plane that’s supposed to retrieve the scientists explodes mid-air, and something breaks into the research station and slices through the radio equipment with surgical precision. The next to disappear is Dr. Jules Deveroux (Mel Welles), who also starts speaking to the research party from beyond the grave. Meanwhile, searching the tunnels under the island, the team soon realise that they are dealing with radioactively enhanced land crabs. But not only are they huge, they are also seemingly invulnerable, as the radioactivity has broken up the atomic bindings, allowing bullets and blades to pass through their bodies with no harm done. But there’s more: the crabs have superpowers. It is they who have been causing the sinkholes, and the erosion of the island. They also devour people — they not so much eat us, but through their impossible atomic structure are able to incorporate us into their beings, minds and all, which is how they have been able to use the voices of the dead call out to the scientists. No magic here though, this is pure science — they “speak” to us by causing vibrations in metal objects.

Soon one after the other of the expedition fall pray to the crabs. The humans seem to get the upper hand when Dr. Weigand (Leslie Bradley) and hunky technician Hank (Russell Johnson) realise that the crabs can be killed with electricity, and construct a trap that looks like two modified fans. However, Weigand literally steps in it, and gets electrocuted by his own trap. Finally, three survivors — Hank, Martha and Martha’s boyfriend Dale (first-billed Richard Garland) are trapped on the last dry spot of the sinking island, which holds a radio tower, and face off against a crab monster.

Attack of the Crab Monsters, produced and directed by B-movie king Roger Corman, is my first film entering the brave new year of 1957. A long year it is going to be for me, as somewhere around 100 science fiction movies were produced this year in Hollywood alone. Corman himself made 11 films this year. Roger Corman entered the scene in 1954 as an inexperienced but driven movie maker, and by 1957 he was hitting his stride. By now he had a dozen or so productions under his vest, and had perfected his sublime art of shooting films cheaper, faster and more effectively than anyone else in Hollywood. He had gathered around his a crew of devoted miscreants, who were willing and suited for his style of one-shot guerilla filmmaking. Perhaps most importantly, he had found a writer to match his toungue-in-cheek humour, as well as his thematic approach, in Charles Griffith, with whom he first collaborated on the surprisingly taut SF thriller It Conquered the World (1956, review). According to Griffith, for Attack of the Crab Monsters, Corman gave him a challenge: to write a script where every scene included either an element of action or suspense. Griffith carries out the task beautifully, adding a number of gimmicks, which in turn create new plot twists and suspense in subsequent scenes. While this does give the film a somewhat episodic feel, the script never loses focus from the main story, and ties in the different strands to the crabs — not always neatly, but still.

Attack of the Crab Monsters was not made for Corman’s usual production company, American International Pictures, but for Allied Artists, for whom the director/producer freelanced from time to time. He made the film alongside the well-respected Not of This Earth (review), and the two were released by AA as a double bill. Not that the temporary switch to the marginally more prestigious production company made much difference. Corman still worked with a shoestring budget, a skeleton production crew and shot Attack of the Crab Monsters over a week or so (according to Russell Johnson, it was closer to a two-week shooting schedule). As was often the case, Corman didn’t bother to rent a studio, but shot almost the entire film on location for free, with one exception: he did rent a pool for a day at the Rancho Palos Verdes Marineland for underwater footage. You can tell, because you can clearly see the side of the tank in some shots. Apatrt from this much of the film was shot at the Leo Carrillo State Beach and some of it at the Santa Catalina Island outside Los Angeles. The research station is clearly filmed as someone’s private home, possibly Corman’s own. Cave scenes and rocky hills were, naturally, filmed at the go-to locale for low-budget Hollywood filmmakers, the Bronson Canyon.

The thing about Roger Corman, however, is that even though he reuses sets and locations, he seldom feels repetitive. Instead of renting a small, cramped studio where he could build three set walls between which to film a majority of a film’s dialogue, Corman would stake out locations that could be reused without actually reusing the same background. Often he would plant his camera in places where he could get three or four different setups without ever moving the camera more than doing a 90 degree swing on his tripod. Plus, even though he shot films quickly, and was reportedly very good at thinking on his feet, Corman was a meticulous planner who usually had all shots thought out in advance. And when it came to his key crew and “stock company” of actors, they were mostly in the loop and well prepared. For example, in an interview with Tom Weaver, Mel Welles, who played one of the leads in Corman’s cult film Little Shop of Horrors (1960), the reason they were able to shoot that film in two days was that the actors had been rehearsing for three weeks and did it like a play.

Another thing about Corman, as I have pointed out in previous reviews, was that he was fearless in his camera use, resulting in a dynamism seldom present in these kind of low-budget films, which often give away their budget and shooting schedule through static, drawn-out shots. Corman didn’t eschew one-shot scenes, but they were seldom stiff and static. He often had his actors move around the set and each other, so instead of cutting from one facial close-up to another, the actors simply switch positions 180 degrees in-shot. There are beautiful examples of this, for example in It Conquered the World (1956, review), which also showcases Corman’s courage with a moving camera, turning what could have been a static set piece of four actors standing in line into a wonderfully dynamic scene. One advantage Corman had in shots like these was that he often shot on location or in real homes, giving him the possibility to film almost 360 degrees, ceilings, floors and all. And where other directors might have avoided underwater scenes because of their cost, technical requirements and not least safety considerations, Corman just plunged in, alas, sometimes disregarding the well-being of his cast and crew. Of course, his method also resulted in gaffes here and there, gaffes he was often aware of, but counted on the audience not noticing or not caring.

A third thing about Corman is that his scripts were seldom quite routine — there’s almost always an interesting idea and some thematic seriousness behind his movies — even if the often befuddling scripts don’t always do these ideas justice — Attack of the Crab Monsters is a good case in point. The script isn’t really about giant crabs — the monsters could have taken any size, shape or form. It is their seemingly supernatural powers that make them such interesting monsters. The monsters absorb the flesh and minds of their victims, creating a menace that had not been seen on screen before. Sure, the alien body snatcher motif had been used and overused by 1957, but in these cases the stranglehold that the communis … ahem aliens had on their victims was almost always purely telepathic. It was also a clear-cut domination, the aliens taking full control over the minds of their victims. This is the case even in the splendid Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review). In Corman’s films, especially those penned by Charles Griffith, the issue was seldom this simple. In It Conquered the World, the aliens need Lee Van Cleef as himself, and convince him that body-snatching the rest of Earth’s population is actually a good thing. In Attack of the Crab Monsters, we can never be quite sure to which extent the voices communicating from the amalgam entities that are the crab monsters are actually coming from the people they used to belong to. We don’t know exactly what happens when they are absorbed. Are they still self-aware and have found new happiness and bliss in their new host organisms, or have the crabs simply absorbed their memories and use their voices as bait for luring the rest of the party in. Wholly new (well, almost) in film is also the idea of a host organism that absorbs the living flesh and minds of their victims. Some similar degree of body horror could be seen in Hammer’s cult classic The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review), where an alien entity takes posession of an astronaut’s body, causing it to mutate into what becomes in the end a hideous blob. Similar shudders were to be had from the scenes of the incubating pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Of course, Corman didn’t have the effects budget to show any of his gory horror on screen, but the whole business almost becomes even more effective as an off-screen imagination.

Now — despite all of the above, Attack of the Crab Monsters is still a super-low-budget movie filled with silliness, awkward dialogue, a preposterous story, hammy acting, lousy production value, gaffes, gigantic plot holes, bizarre leaps of logic, and last but not least, a hilariously bad monster suit/puppet.

There are a number of famous gaffes in the film. One is the piece where one of the characters, in the beginning of the film, comments on the silence — followed by a scene of a flock of screeching seagulls. Another one, also in the beginning, sees a marine soldier fall out of the boat (played by screenwriter Griffith) in the shallow waters near the beach — only to sink to a depths of several metres, where he is decapitated by a crab monster. A third famous gaffe is that you can reportedly spot a pair of tennis shoes beneath the crab suit at some point in the film. Ed Nelson, who was inside the suit, says his shoes were visible in one of the promotional stills of the movie, and that in one scene, the still was inserted when apparently no suitable film shot was to be found.

In a way, it’s a shame that Corman specialised in cheap monster movies, for which he never had enough of a budget to create convincing monsters. As such, many of these movies hold up fairly well as horror thrillers, but are best remembered for their laughable monsters. But Corman knew what he was doing: a monster on the poster sold tickets, and that was his main goal, as he has repeatedly stated himself; not to make good pictures, but to make pictures that made money. He tried early on to leave out the monster by making it operate solely on a telepathing level, in The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955, review), but was met with angry test audiences, who expected to see the monster depicted on the poster and name-dropped in the title.

The crab monsters were not created by Corman’s go-to monster maker Paul Blaisdell. Blaisdell was consulted, but when hearing he had a budget of $400 to create a giant animated crab, he refused. So instead, the monster was ordered from a prop company, with the same budget, and the result mirrors the input. Actually, it’s pretty impressive for having cost only $400. It lacks the mischievous attitude and spikyness that Blaisdell often gave his creatures, and as such has less character. But it does look like a crab and it is kind of gnarley. It does not move very fast or all that much at all, though, and Corman makes good use of some creative editing in order to create action. When it attacks, we mostly see a pincer emerge from behind the camera — partly this helps keep the suspense, but it also shows the lack of coordinated movement in the prop. The suit/prop itself was designed for one person to operate from the inside, crouching. This job fell to Ed Nelson, one of Corman’s stock people, and his main task was to give the crab locomotion by carrying the suit on his shoulders. He also had to levers with which he operated the eyes. The legs and pincer arms were suspended from piano wires, that were attached to long poles held by crew off-screen, operating the legs like a giant marionette. The result isn’t particularly dynamic, but it works! Sort of.

Attack of the Crab Monsters is not Corman’s best 50’s SF movie, but neither is it his worst. The script is not as strong as that of It Conquered the World, nor is the acting or the direction. However, it is highly entertaining and moves swiftly from action to action, with well-paced mystery in between, and has a bunch of highly original, if outrageous, ideas.

Variety wrote at the time of the film’s release: “It isn’t believable, but it’s fun”. The Ehxhibitor was not as lenient, focusing on the cheap production values, the hokey monsters and “walkthrough performances”. According to the paper, the film did not create the intended horror. However, it praised the underwater photography. Harrison’s Reports, however, gave a fair review, noting that the film “should prove satisfactory to the horror addicts”.

Today the film has a 4.9/10 audience rating at IMDb and a far better 7.0/10 rating at review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes, along with a 71% Fresh rating, marking one of those instants where a schlocky B-movie is, paradoxically, more popular with critics than with the general audience. AllMovie gives it a 3/5 star rating, with Oliver Firsching calling it a “a silly but lovable sci-fi cheapie” which “will delight genre buffs”. At Trailers from Hell, Glenn Erickson gives Attack of the Crab Monsters a glowing review (noting that this doesn’t mean it’s Solaris), praising Corman’s efficient, streamlined storytelling, the strong editing, interesting ideas and enthusiastic performances. At Radio Times, Alan Jones calls the film “lunatic but fast-moving fun”.

Of course, this film is not for everyone, as Polish blogger “Andmel” at Horror Online demonstrates. Those coming to this film expecting “horror” in the modern sense, will of course be disappointed. “Andmel” notes the film’s cheap production values, lack of atmosphere and “shallow, schematic script”. They conclude: “Today, […] it can only be considered in terms of fun, nostalically looking at the naivety of the production, and not as a film that is supposed to scare us. It stands out as somewhat different than most films in the deluge of monster movies of the period.” Or, as German critic Oliver Nöding economically puts it at Remember It for Later: “There is actually no need to waste words: If you love monster nonsense from the fifties, you’ve come to the right place”.

I have written extensively about Roger Corman in previous articles, so just click his name in this sentence learn more. In short, Corman, an engineer by trade, started making films in the early 50’s when he realised he could make the same movies that studios made for $300,000 for a tenth of the sum by cutting overhead costs, working with a skeleton crew cutting corners generally everywhere. He quickly impressed newly formed American International Pictures as both a producers and a director who would turn over pictures fast, cheap and reliably, and whose work was good enough to actually make quite a lot of money at the box office. AIP and Corman tapped into the generally overlooked new market segment of teenagers with time and a bit of money on their hands. Corman, in particular, had a knack for horror and science fiction, although he made movies in pretty much every conceivable genre.

In the 60’s Corman solidified his reputation not only a B-movie hack, but as a talented director, with his famed Edgar Allan Poe adaptations and his sojour into the burgeoning biker subgenre, laying the groundwork for such films as Easy Rider (1969) with his pioneering movie The Wild Angels (1966), again shrewdly picking up on cultural shifts before the major studios, in order to reached new and untapped audiences. In the 70’s, B-movies of the kind Corman made were pushed more and more into the drive-in market, which had a fast turnover, and required producers like Corman to keep pushing out films at an incredible pace. He specialised in “girls behind bars” movies, and made some of the best in the genre. He stepped away from directing, for the most part, instead giving opportunities to unproven directors, like Jonathan Demme, whose first effort was the “girls behind bars” film Caged Heat (1974). But during the 70’s Corman also managed to produce some splendid cult classics, like Boxcar Bertha (1972, by Martin Scorsese), The Twilight People (1972, Eddie Romero), Death Race 2000 (1975, Paul Bartel), Grand Theft Auto (1977, Ron Howard), Deathsport (1978, Allan Arkush), Piranha (1978, Joe Dante), Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (1979, Arkush, Dante) and Saint Jack (1979, Peter Bogdanovich).

Corman has officially directed only one film since 1971, and that was only because he was paid a million dollars to do so. However he has continued to produce films at an astonishing rate, racking up at least 500 productions between 1955 and 2021. In the process he has created an unofficial film school into which he has invited struggling actors and filmmakers who have been desperate enough to do anything and everything for almost nothing, and learn the process of making movies from the ground up from a master. The alumni of “Corman University” are too many to namedrop here, but please check out the great mini-documentary The School of Corman by film critic and author Robin Bailes at Dark Corners Reviews.

In the 80’s and 90’s Corman stayed with the times, producing numerous slashers, science fiction movies, sword-and-sorcery films and post-apocalyptic action films. Many of the schlocky franchises of the era stem from Corman’s production, such as Bloodfist, Deathstalker and Watchers, and he didn’t look down on straight-out erotica, such as a numerous Emmanuelle and Caged Heat sequels and original franchises like Body Chemistry. Disparaged by the streamlining of movie theatres, and by the fact that the sort of B-movies he made in the past were being picked up as A-listers by major movie companies in the wake of films like Alien (1979) and The Terminator (1984), he chose to release an increasing number of films as straight-to-video output, often helmed by young filmmakers who went on to successful careers. In 1993 Corman took advantage of the massive build-up to Jurassic Park (1993) and snuck Carnosaur onto the market before Spielberg’s film was released. In 2004 Corman produced the GCI monster movie Dinoshark, birthing a whole new genre, and followed up with such schlockers as Scorpius Gigantus, Supergator, Dinoshark, Sharktopus, Piranhaconda and many more, opening the doors for rival company The Asylum to produce Sharknado in 2013, which, like Corman’s output, was released through the SyFy Channel. His latest producing credit is for Peruvian director Rey Cajacuri’s The Jungle Demon (2021), and at the age of 97 he is still active in the business.

The nominal lead in the film is Richard Garland, riding high on good press for a small role in William Wyler’s star-studded Friendly Persuasion (1956). While never a marquee name, Garland carved out a decent career as a supporting actor in film and TV, most notably in Lassie, before his untimely death caused by alcoholism in 1969, only 41 years old. In 1951 he married actress Beverly Garland, who divorced him in 1953, but kept his name — Beverly also appeared in a number of Corman movies, most importantly, perhaps, in It Conquered the World, opposite Peter Graves and Lee Van Cleef.

But the real hero of the film is Russell Johnson, owing to his everyman charisma, good looks and some serious acting chops. Johnson was picked up by Universal soon after his film debut in 1952, and appeared in the SF movies It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), as one of the body-snatched telephone linemen, and This Island Earth (1955, review), as Rex Reason’s confidante at the mysterious mansion. Realising that Universal was grooming a new cohort of leading men, and he was rather low on the list, he left the studio, and continued as a freelancer, primarily in low-budget movies and TV. He appeared in The Space Children in 1958, and a number of sci-fi TV series, including The Twilight Zone (1960-61), The Outer Limits (1964), and Wonder Woman (1978). He revealed in a later interview that he had wanted to appear in the original Star Trek series, but was never cast. He will always be best remembered, however, for playing the Professor in the beloved TV series Gilligan’s Island (1964-1967), and its numerous film adaptations and spinoffs, including the slightly less loved sci-fi series Gilligan’s Planet (1982).

Pamela Duncan puts in sincere work in the female lead, one of her two leading roles in her career, the other was another Corman vehicle, The Undead, again opposite Richard Garland. Duncan entered movie business in 1950, with a background as a beauty pageant, and carved out a decent career as a “decorative presence” in movie bit-parts and as a guest star on many TV shows. Her career teetered out in the early 60’s.

Leslie Bradley was an in-demand supporting actor born in England with an accent and face that made him popular with casting agents for period dramas. He is perhaps best known for his turn alongside Burt Lancaster in The Crimson Pirate. He also appeared in the musical time travel comedy Time Flies (1955, review) as Sir Walter Raleigh and teamed up with Corman once more in Teenage Caveman (1958, review).

A character indeed was Mel Welles, here playing French scientist Deveraux. Big, loud, charismatic and over-the-top, Welles brought colour and character to numerous Corman films, but is most fondly remembered for his role as the shop-owner of Corman’s classic horror comedy Little Shop of Horrors (1960). Welles enjoyed a reasonable career as a bit-part and supporting actor in Hollywood, but in 1960 travelled to Germany, only to enjoy life in Europe so much that he stayed, carving out a career as an actor, writer, producer and director, often uncredited. He directed, among others, the cult movies Maneater of Hydra (1967) and Lady Frankenstein (1971). Being fluent in five langauges, he started a dubbing company, which, in his own words, dubbed over 800 European films in English. He eventually returned to uthe US where he continued his career both behind and in front of the camera, primarily in Z-movies, including Chopping Mall (1986), Invation Earth: The Aliens Are Here (1988) and Raising Dead (2002). Welles also wrote the famous beat poem “High School Drag” performed by Philippa Fallon in High School Confidential (1958).

Richard Cutting was a well-employed bit-part player, mostly in westerns, from the early fifties until his death in 1972. However, to Americans of the boomer generation he is probably remembered primarily as Manners, the tiny butler, in a series of tv ads for Kleenex table napkins, the ones that “cling like cloth. Thank you”.

Ed Nelson, who played the crab, had some TV, radio and stage experience before arriving in Hollywood in the mid-50’s, and promptly became one of the key members of Roger Corman’s stock company, doing a bit of everything and anything, often uncredited. After his stint with Corman, Nelson made himself a name as a TV actor, and hit mainstream fame as one of the leads in the soap opera Peyton Place (1964-1969). Along with Barbara Parkins, he was the only actor to appear in both the first and the last episode, and to be credited in every episode. Nelson also appeared in Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review), The Brain Eaters (1958, review), Teenage Caveman, Night of the Blood Beast (1958, review), Deadly Weapon (1989) and Jackie Chan’s Who Am I? (1998).

Janne Wass

Attack of the Crab Monsters. 1957, USA. Directed by Roger Corman. Written by Charles Griffith. Starring: Richard Garland, Pamela Duncan, Russell Johnson, Leslie Bradley, Mel Welles, Ed Nelson, Richard Cutting, Beach Dickerson, Tony Miller, Robin Riley, Doug Roberts. Music: Ronald Stein. Cinematography: Floyd Crosby. Editing: Charles Gross, Jr. Makeuop: Curly Batson. Special effects: Ed Nelson. Produced by Roger Corman & Charles Griffith for Allied Artists.

Leave a comment