A mad scientists kills wrestlers and turns them into super-monsters. An up-and-coming wrestler agrees to act as bait for the killer, with disastrous results. The first Mexican luchador/monster mashup from 1957 may be the best. 6/10

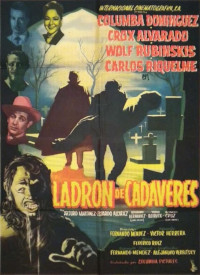

The Body Snatcher. 1957, Mexico. Directed by Fernando Mendez. Written by Fernando Mendez & Alejandro Verbinsky. Starring: Columba Dominguez, Crox Alvarado, Wolf Ruvinskis, Carlos Riquelme, Yerye Beirute. Produced by Sergio Kogan. IMDb: 6.5/10. Letterboxd: 3.3/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Police captain Carlos Robles (Crox Alvarado) is stumped. Someone is killing Mexico’s top athletic fighters, and their bodies are found with signs of some horrific brain surgery. Despite posting men at Mexico City’s top gym, where all the best martial artists, boxers and wrestlers train, the nefarious murderers are able to snatch the bodies right under the their noses. But captain Robles has a heureka moment when he is visited by his old friend Guillermo Santana (Wolf Ruvinskis), a rancher who dreams of becoming a wrestling star. Knowing Guillermo has the chops to take on anyone in the ring, Robles devices a plan to turn Guillermo into the next big lucha libre star, the masked marvel El Vampiro, and use him as bait for the mad murderer.

Ladrón de Cadáveres, or The Body Snatcher (1957) is something of a milestone in Mexican cinema, as it is the first film to combine the Mexican form of show wrestling, lucha libre, with mad doctors and monsters. It was directed and co-written by Fernando Mendez, who later the same year would direct The Vampire, which really opened the floodgates for Mexican horror. Among the cast of The Body Snatcher are some of the most important figures in lucha libre movies.

The audience is quickly made aware that the murders are orchestrated “Professor” (Carlos Riquelme), who is a master of disquise and poses as a poor lottery salesman at the gym, scouting his prospects. The murders are carried out by the Professor’s henchman Cosme (Yerye Beirute), who we see stab wrestler El Lobo Negro (Guillermo Hernández) in the shower, and smuggle him out in the laundry basket. The victims are taken to the Professor’s Frankensteinean lab, where their brains are swapped with those of apes. The Professor’s aim is to create an army of supermen, that presumably, in the words of the late great Bela Lugosi “which will conquer the voorld! he he he…” But instead, his test subjects have been dying on the operating table, which is why the police have been finding bodies instead of supermen.

Guillermo is initially hesitant about risking his life by becoming bait for a murderer, but he comes around when captain Robles, his old friend, reminds him of the fortune and fame he would receive as Mexico’s top luchador. Even if his newfound girlfriend, police secretary Lucía (Columba Domínguez) is not thrilled with the idea, Guillermo agrees, and “El Vampiro” makes a meteoric rise to the top of the lucha libre world, becoming and equivalent of real-world wrestler superstar Santo.

But despite the bumbling police force’s best efforts, Cosme and the Professor are able to poison Guillermo at the wrestling stadium, and he literally drops dead in the middle of a match, even though Robles corners and kills Cosme. The Professor’s assistant (Ignacio Navarro) snatches Guillermo’s body from the morgue, again outwitting the police, and brings him to the lab, where the Professor swaps his brain with that of a gorilla, and finally succeeds to keep his test subject alive. Guillermo now acquires super-strength, and becomes a zombie under the Professor’s telepathic control.

Meanwhile, the police are giving it a second shot with El Vampiro II. The Professor has other plans, and sends Guillermo to kill the impostor, and take his place in the ring as the masked superstar. However, after having flung his opponent into the audience like a rag doll, Guillermo goes off program, rips off his mask to reveal a monstrously mutated face, and attacks the audience, that flees in panic. The Professor confronts him, but can no longer control his creation, who impales him on a spike protuding from a wall. Mutating into a bona fide ape man, Guillermo’s old instincts kick in, and he abducts the sleeping Lucía, and is chased by Robles and the police to a rooftop, where Robles tries to confront his old friend. However, Guillermo has left the building and is now in full ape mode. He attacks Robles, theatening to push him off the roof, when Robles’ colleagues shoot him, and he tumbles down ten floors, and is crushed on the pavement. Wrecked with guilt over what he has done to his best friend and to Lucía, Robles makes sure Guillermo receives a posthumous medal of honour.

Background & Analysis

By 1957 the Golden Age of Mexican cinema had passed. The country’s film industry was deemed by many as having falling behind the world’s leading movie industries technically and thematically, and domestic movies failed to engage audiences. Spanish director Luis Buñuel left Mexico in 1953 for greener pastures, and the old rumberas and charro movies starring superstar comedians Cantinflas and Tin Tan that were once the cornerstone of Mexican cinema, while still popular, were being deemed old-fashioned. In turn, foreign films dominated the Mexican and Latin American market.

Looking for new ways to draw in the audience, film studios turned to the luchadores, the show wrestlers of Mexico. Luchadores had featured in movies prior to the fifties but the first movies to explicitly cater to the lucha libre fans was La bestia magnifica (1952) and Huracán Ramírez, (1953). The films have little in common with what we now associate with luchador movies. Rather than portray the fighter of the title as a crime-fighting superhero, the films were melodramas set in the lucha libre world. Nonetheless, they were moderately successful, and opened the gates for more similar movies.

Santo was by this time the superstar of lucha libre, and producers saw in him the possible cash cow to turn Mexican cinema around. However, Santo was wary, fearing that involvement in a bad movie could hurt his image and career. When they couldn’t get the real “Silver Masked Man” onto the screen, they turned to the next best thing, Cesáreo González, or El Medico Asesino, and in 1954, future horror and luchador movie legend René Cardona directed El enmascarado de plata, or “The Silver Masked Man”, starring El Medico. While not a huge hit, the film was commercially successful, and established the trope of the masked luchador as a vigilante crime fighter. The film was followed by others, starring Fernando Osés as La Sombra Vengadora (The Avenging Shadow), which were also moderately successful.

These films were modelled on US crime serials, with the luchador solving mysteries and chasing down mysterious, masked villains, often using futuristic gadgets and weapons, and were made on extremely low budgets. The Body Snatcher was a game-changer. The film had a proper budget, great cinematography and a competent director, and left behind it the low-budget trappings of the Hollywood serial, instead drawing its inspiration from horror movies and film noir. It was the first movie to combine the luchador genre with the monster movie and the mad scientist movie. Director Fernando Mendez went on to revitalize the Mexican horror film with The Vampire (1957), whid DID become a huge hit, and was followed by cult classics such as The Aztec Mummy (1957), The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy (1958) and The Black Pit of Dr. M (1959). While not luchador films as such, many of these featured stars from the wrestling ring, not least Crox Alvarado, who had become a bona fide B-movie star in his own right.

Seeing the growing popularity of the luchador films, Santo was finally convinced to join the fray in 1961, with Santo vs. the Evil Brain. And in 1962, all the separate genre strands finally aligned with Santo vs. the Zombies, giving us a film in which a masked superhero luchador fights monsters — a trope that would become almost ubiquitous with the luchador movie genre. But — it was The Body Snatcher that laid the foundation.

The Body Snatcher, or Ladrón de cadáveres, probably borrows its title from Val Lewton’s 1945 film with the same title, starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. That, in turn, was based on R.L. Stevenson’s 1884 short story. Little of Stevenson’s or Lewton’s psychological horror story and moral drama is present in Ladrón de cadaveres, if course. In fact, the movie is actually a reworking of another famous horror story, Frankenstein. American horror movies were hugely popular in Mexico from the 30’s onward, in particular gothic classics like Phantom of the Opera, Dracula, Frankenstein and The Mummy. Mexican filmmakers mined these films for all they were worth, often changing just enough to avoid copyright lawsuits. Ladrón de cadáveres isn’t quite a Frankenstein-ripoff, but the basic idea is clear enough for all to see.

The movie begins with a gothic scene of the Professor and his henchman stealing a body from a graveyard, complete with crows and fog, promising a Universal-style classic horror story. However, this is all we get in that regard. The movie quickly switches into the urban settings of Mexico City in 1957, taking place primarily in the gym, rather than an old castle. However, Ariel Award-winning cinematographer Victor Herrera still delivers moody scenes, borrowing heavily from film noir. The streets are perpetually dark and foggy, and Herrera makes good use of the juxtaposition of light and shadow.

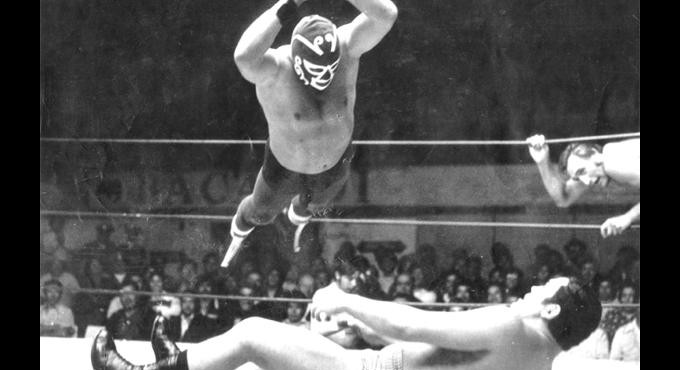

Much of Mendez’s direction is pedestrian, but there are several excellently filmed scenes. One stand-out is the scene where the audience at the wrestling stadium flees the ape man. Rather than a few dozen extras, Mendez seems to have actually had a sizeable audience to work with, and does beautiful work with capturing the pandemonium. The lab scenes are another sign that The Body Snatcher had a slightly bigger budget than previous luchador movies. There’s a rather impressive and even technically functioning machine dominating the design by Ariel Lifetime Award recipient Gunther Gerszo. The wrestling scenes are very well choreographed and feel visceral. However, they are a bit flaccidly shot. Especially the fights at the stadium would have benefited from more close or even medium shots – now they are filmed completely in wide shots.

The monster makeup by Margarita Ortega is serviceable at best, but Mendez wisely refrains from shooting it in close-up and keeps it obscured in the shadows most of the time. Likewise, the transformation scenes are hinted at, rather than shown.

The plot of the movie is refreshingly straightforward and easy to follow. I watched the film on Youtube with auto-generated English translation and had no problem whatsoever to follow the proceedings. Of course, it is also bonkers. As is often the case with these mad scientist films, the mad scientist’s motivation for creating monsters is somewhat hazy. The Professor says he is going to create an army of supermen, but what he is actually going to do with this army is hazy. What the purpose of making ape Guillermo compete in wrestling? How replacing Guillermo’s brain with that of a monkey would give him super-strength is also never explained, nor how placing the ape brain in Guillermo’s body would suddenly give the Professor telepathic control over it. Why is the ape’s brain attracted to Lucía, and why does it know where she lives? And why does it react to the name Guillermo? But of course, these are the standard tropes of ape-man-brain-swap movies.

It’s a surprisingly tragic film. The lead actor is manipulated by his best friend into becoming bait for a mad scientists, who kills him, cuts out his brain and replaces it with that of a gorilla. Then he kills the mad scientist, but instead of a thank you, he is shot and killed by the police, leaving his girlfriend, who warned him about agreeing to help the police, heartbroken and alone. There’s not even the standard Hollywood trope of the “replacement boyfriend” waiting in the wings. Instead, she has to go back to work with the man who manipulated and had her boyfriend killed. The real villain of this piece is police captain Robles.

The acting in The Body Snatcher is, on the whole, serviceable. Carlos Riquelme as the Professor is the standout, excelling in the diguised role as the poor lottery salesman, creating a likeable old beggar with nefarious intentions. It really is a masterful performance, as you wouldn’t recognise Riquelme “out of disguise” as the Professor. Columba Dominguez, a respected dramatic actress, is wasted in a nothing role. Former wrestlers Crox Alvarado and Wolf Ruvinskis are, as stated, serviceable. Ruvinskis does a good ape man, perhaps the most physically able ape man on film in the 50’s. Yerye Beirute is, as always, a wonderfully sinister presence as the henchman.

As far as luchador movies go, The Body Snatcher must be one of the best. It’s not as bizarrely bonkers as later entries, and director Mendez refrains from turning it into a camp fest. The story is played straight and Mendez directs with style and atmosphere. The plot itself is engaging, even if it takes a while to get moving. The romantic subplot is not particularly well written by Mendez and co-writer Alejandro Verbitzky. The wrestling scenes are somewhat drawn out, but on the other hand, nobody sits down to watch a 1950’s luchador film for its witty dialogue.

Reception & Legacy

Ladrón de cadáveres premiered in late September, 1957 and was a moderate success. I have not found any contemporary reviews. Neither are you likely to find reviews in major movie media. The film has a 6.5/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on 200 votes, and a 3.3/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on around 250 votes.

Hispanic online critics (I assume Mexican, but can’t find any information on this on their blogs) give the film high praise. Mario Salazar on Nenufares Efervescentes calls it “not only an entertaining film but also a good B-movie horror film”. Felix H. Ponce at Alucine Cinefago writes: “It is extremely well directed, with great artistic talent, harmoniously and very successfully combining gothic horror with police intrigue and the luchador subgenre. Highly recommended.”

English-language writers tend to agree, albeit with some caveats. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings opines: “this may be one of the best of the Mexican horror movies”. Kevin Lyons at EOFFTV Reviews agrees: ” It’s well made, nicely acted by all involved and yet still shot through with that weirdness that we’d become so familiar with from later Mexican films. […] The Body Snatcher isn’t quite as striking as El vampiro but it’s still one of the best of the 50s and 60s Mexican horror/luchador films.” Jeff Stafford at Cinema Sojourns writes: “Compared to later, more grisly Mexican horror pictures like Rene Cardona’s Night of the Bloody Apes (1969), The Body Snatcher will be s-l-o-w going for contemporary audiences but for former monster fans of the Universal horror classics, the movie is a nutty delight with several memorable sequences.” Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster is disappointed there isn’t more of the gothic atmosphere on display at the beginning of the movie, but: “Still, it’s not a bad example of the Mexican horror film and it should keep the fans happy (particularly the Lucha Libre fans). Yes, Mexican horrors like Monster, The Bloody Pit of Terror or The Skeleton of Mrs. Morales are better. But then, they don’t have any masked wrestlers, do they?” Finally, Mike Haberfelner at Search My Trash says: “The very first lucha libre film to tackle science fiction and horror, Ladrón de Cadáveres is really restrained in its approach in comparison to later horror/wrestling movies, and it refrains from being too formulaic, too. That’s not to say this is a piece of art or anything, it’s still more of a simplistic cross between crime flick, sci-fi horror and of course lucha libre, with the finale borrowing from King Kong quite heavily, but it’s awesome fun to watch and sure has this naive charme of yesteryear’s pulp cinema.”

As stated, The Body Snatcher was successful at the Mexican box office, and it got a theatrical release at least in the US, Japan, France and Germany, as well as, naturally, many Latin American countries, and I would assume, Spain. However, it has been overshadowed by the success of Fernando Mendez’s The Vampire, and is seen as little more than an obscurity today, despite the fact that it was instrumental in ushering in the luchador vs. monster genre.

Cast & Crew

As stated above, there is little information on director Fernando Mendez available at my usual sources, speaking perhaps to his stature within Mexican film history. Mendez received few accolades during his career as a director between the early 40s and early 60s, but has been somewhat re-evaluated by Mexican cineastes in later years. By the time he made The Body Snatcher, he was already a household name in Mexican cinema, having excelled in bringing several popular films in the entertainment vein to theatres, such as the crime melodramas El Suavecito (1951) and As negro (1954), the western Los tres Villalobos (1955) and the rock ‘n roll movie La locura del rock and roll (1957).

Born in 1908, Mendez studied art before deciding on a career in the movies, inspired by his uncles, local Michoacan film pioneers Pedro and Francisco García Urbizu. In 1929 Mendez moved to Hollywood, where he worked with various tasks, such as makeup and sound, on a number of film sets, including Dwain Esper’s cult classic exploitation films Sex Maniac (1934) and Marihuana (1936). He returned to Mexico in 1936 and worked for a while as a screenwriter and made a couple of short films before making his feature debut in 1941.

But it’s Mendez’s six horror movies, made between 1957 and 1959, that has brought him international recognition, starting with The Body Snatcher, which was the first movie to successfully merge the luchador and monster movie genres. The ones considered his best, and most well known, are The Vampire (1957) and The Vampire’s Coffin (1958), praised for the way in which they manage to relocate the Dracula myth from the Transylvanian mountains to a rural Mexican hacienda. He followed these up with The Black Pit of Dr. M (1959), The Night Riders (1959) and the weird west movie The Living Coffin (1959). Illness forced Mendez to quit directing in 1961, but he continued writing scripts for other directors until his death in 1966.

Crox Alvarado was born Cruz Pío Socorro Alvarado Bolado in Guadalupe, Mexico, in 1910, and and El Salvador on account of his father’s work. After studying accounting and in 1930 found work as a caricaturist at a leading film magazine, and also entered the rapidly growing lucha libre scene. At the newly refurnished Arena Modelo, Crox Alvarado became one of the pioneers of the sport, when the “father of lucha libre”, Salvador Lutteroth, brought show wrestling from Texas to the arena in Mexico City. The first Mexican-made sound picture opened in 1933, ushering in the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. Alvarado’s friend, famous singer and stage and radio performer Jorge Negrete made his film debut in 1937 and encouraged Alvarado to do the same. His first roles were mostly bit part, but he impressed directors not only with his athletic physique, but also with his talent and versatility as an actor. He didn’t only play brawlers and henchmen, but a number of different roles in all conceivable genres. His breakthrough came with a leading role in the melodrama Naná (1944), oppositie Mexican Hollywood star Lupe Velez. By now Alvarado had left wrestling behind and focused on his work as a caricaturist and actor. The role won him a regard as a serious character actor and romantic lead.

Crox Alvarado’s next important step was accepting the role of male lead in the 1952 movie The Magnificent Beast (La bestia magnifica), in which he played opposite fellow wrestler Wolf Ruvinskis and “the Marilyn Monroe of Mexico”, Czech star Miroslava. In the film, he played a wrestler struggling up from poverty. Alongwith Huracán Ramírez, The Magnificent Beast ushered in the age of the lucha movie, with Alvarado as one of its biggest stars. In fact, there was a long-running rumour going around that Crox Alvarado and Santo were in fact the same person. The theory gained strength by the fact that despite both making popular lucha films, they never appeared on screen together. That is, until the theory was shattered in 1968, when they played opposite each other in Atacan las brujas, and again in Santo contra Capulina (1969). His golden era as a B-movie hero came when he starred in the hugely popular Aztec Mummy trilogy in 1957 and 1958; The Aztec Mummy, The Curse of the Aztec Mummy and The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy. Between 1952 and his death in 1984 he appeared in over a dozen lucha films, a couple of boxing movies, some horror pictures, countless westerns and stints in romantic dramas, musicals, comedies, historical pictures, etc, and also established himself as a stage actor. To an English-language audience he is best known for appearing in bit-parts in Jerry Warren’s The Face of the Screaming Werewolf (1964), starring Lon Chaney, Jr., and the TV movie Attack of the Mayan Mummy (1964). You may also have seen him as a police inspector in the Batwoman (1968).

Wolf Ruvinskis Manevics was born in Riga, Latvia, in 1921, and his Jewish family fled prosecution by the Nazis to Argentina in the 30s. At the age of 19 he became a luchador, which brought him to Mexico. As The Latvian Wolf, he played a bad guy in the ring, facing off against all the top stars of Mexican show wrestling, until accumulated injuries forced him into partial retirement in the early 50s, allowing him to focus on his other passion, acting. A fixture in B-movies in the early 50’s, like Crox Alvarado, Ruvinksis got his breakthrough in The Magnificent Beast (1952). He often played secondary characters, and The Body Snatcher was his first bona fide leading role, even if he was third-billed below Columba Dominguez and Alvarado. In 1960, he followed in the footsteps ofSanto, and got his own masked superhero luchador character in Neutrón, el enmascarado negro. He played Neutron in a handful of films between 1960 and 1965, movies that have become his most lasting legacy. His SF output include: The Body Snatcher (1957), El superflaco (1959, review), Neutrón, el enmascarado negro (1960), Neutron vs. the Death Robots (1962), Neutron vs. the Amazing Dr. Caronte (1963), Neutron vs. the Maniac (1964), Neutron Battles the Karate Assassins (1965) and Santo vs. the Martian Invasion (1967). Ruvinskis kept on acting until his death in 1999, and appeared in over 120 movies. He was also a magician, an accomplished tango dancer and in later years opened a restaurant.

Columba Dominguez was a respected “serious” actress, winner of a supporting actress Ariel in 1949, and recepient of a lifetime Ariel in 1996. This was a rare outing into genre territory for her.

Character actor Carlos Riquelme was happily cast against type as the mad doctor in The Body Snatcher. Often playing meek, friendly figures like clerks and doctors, Riquelme was a popular actor, receiving three Ariel nominations during his career. He was also appeared in Hollywood movies filmed in Mexico, like John Huston’s Under the Volcano (1984) and Robert Redford’s The Milagro Beanfield War (1988). His SF films include Los platillos voladores (1956, review) and The Body Snatcher (1957). he also worked extensively in radio and as a voice actor.

Costa Rican actor Yerye Beirute (b. 1928) was gifted with a prominent forehead, dark, bushy eyebrows and an angular face, giving him somewhat brutal and almost animalistic features — which served him well in a long line of horror movies, or as a “native” or henchman in westerns and adventure films. He is perhaps best known as he vampire’s assistant in Fernando Méndez’ The Vampire’s Coffin (1958). Outside of the horror genre, he may be seen in small roles in Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966), starring the lesser know Tarzan Mike Henry, and the star-padded Seven Cities of Gold (1955), with actors like Richard Egan, Anthony Quinn, Michael Rennie and Rita Moreno. He also appeared in an episode of the TV series Sheena, Queen of the Jungle (1955).

In the SF department Beirute was on deck on such films as The Body Snatcher (1957), La casa del terror (1960), Alfredo B. Crevenna’s The Incredible Face of Dr. B (1963) and its sequel La huella macabra (1963), as well as two films by René Cardona; Le edad de piedra (1964) and El increíble profesor Zovek (1972). Best known are without doubt two of Boris Karloff’s Mexican movies, directed by Jack Hill and Juan Ibáñez: The Incredible Invasion (1971) and Fear Chamber (1971).

Janne Wass

The Body Snatcher. 1957, Mexico. Directed by Fernando Mendez. Written by Fernando Mendez & Alejandro Verbinsky. Starring: Columba Dominguez, Crox Alvarado, Wolf Ruvinskis, Carlo Riquelme, Yerye Beirute, Felipe Dorantes, Arturo Martinez, Eduardo Alcatraz, Guillermo Hernandez, Ignacio Navarro, Alejandro Cruz. Music: Federico Ruiz. Cinematography: Victor Herrera. Editing: Jorge Bustos. Production design: Gunther Gerzso. Makeup: Margarita Ortega. Sound supervisor: James Fields. Special effects: Juan Munos Ravelo. Produced by Sergio Kogan for Internacional Cinematografia.

Leave a comment