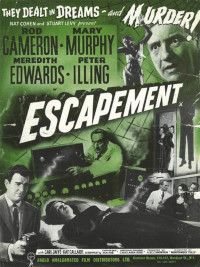

Ex-Nazis operate a brainwashing dream machine in a psychiatric clinic in this 1958 UK mystery melodrama. Released in the US as The Electronic Monster, it squanders a good idea in a programmatic cloak-and-dagger plot. 3/10

Escapement. 1958, UK. Directed by Montgomery Tully. Written by Charles Eric Maine, J. McLaren Ross. Based on the novel Escapement by Charles Eric Maine. Starring: Rod Cameron, Mary Murphy, Meredith Edwards, Peter Illing. Produced by Alec Snowden. IMDb: 4.6/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

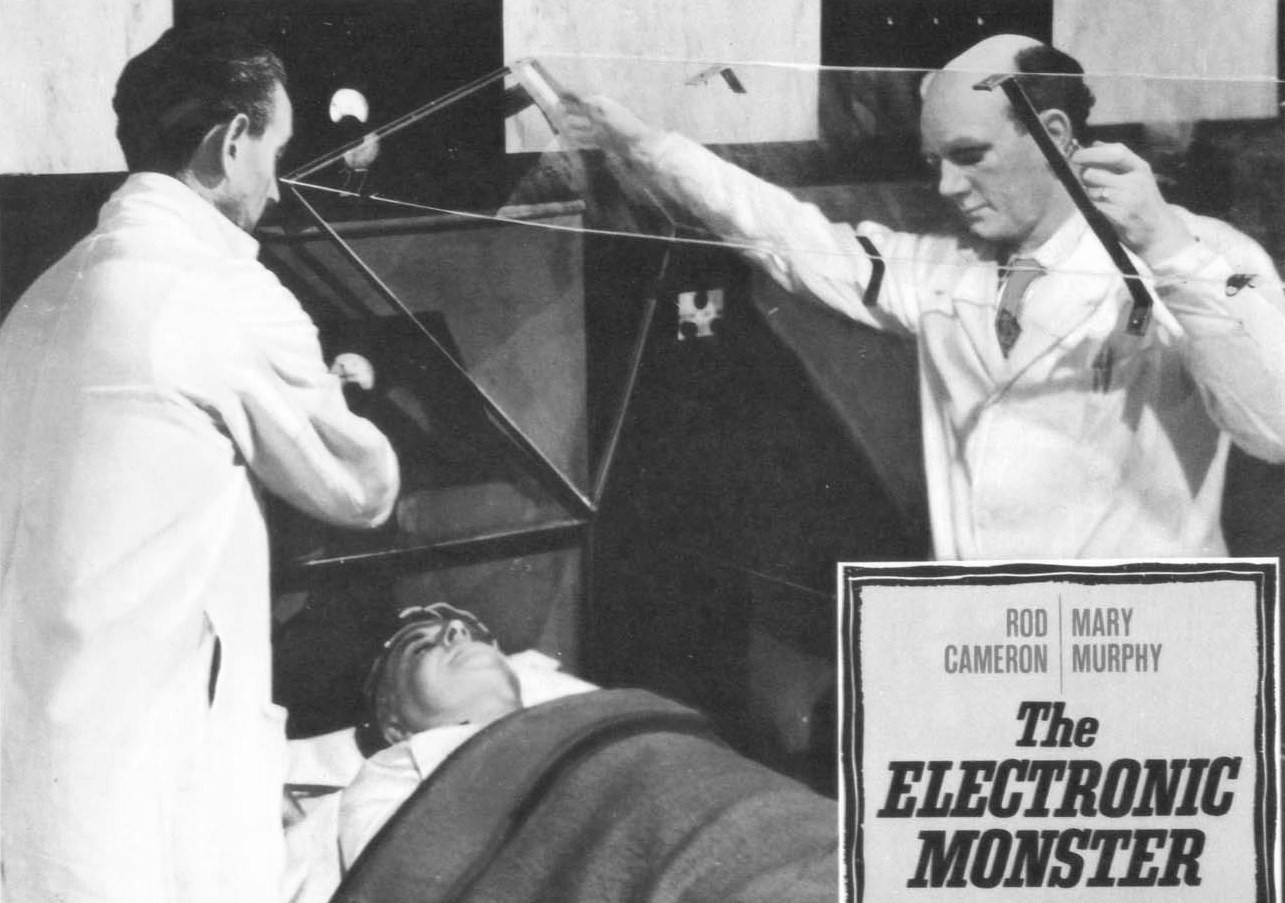

A Hollywood movie star dies under mysterious circumstances while making a film in France, just after checking out from a psychiatric clinic. Insurance investigator Jeff Keenan (Rod Cameron) flies over to investigate, and soon finds that three people have died of mysterious brain-related caused after having been released from the clinic. Head physycian Philip Maxwell (Meredith Edwards) explains that the clinic uses a novel therapy technique that helps patients escape from reality by projecting “films” from tape directly into the brains of their patients. Maxwell is troubled to learn that the treatment may have caused the deaths, and along with his colleague and wife Laura (Kay Kallard) decides he wants to suspend all treatments until the claims can be invested. However, this does not cuit Paul Zakon (Peter Illing), owner of the clinic and producer of the “brain films”. Through his henchman Blore (Carl Duering) he kills Keenan’s contact Somers (Larry Cross) and theatens Maxwell into obedience.

That’s the build-up to the British 1958 low-budget science fiction thriller Escapement, based on Charles Eric Maine’s novel of the same name, later released as The Man Who Couldn’t Sleep. The movie was released in the US as The Electronic Monster.

Now begins a a cat-and-mouse game between Zakon and Keenan, that involves not only Maxwell and his wife, but also a mysterious French woman (Roberta Huby), who seems responsible for finding and directing people to Zakon’s clinic, Maxwell’s colleague, former Nazi scientist Dr. Hoff (Carl Jaffe), who is in cahoots with Zakon, the corrupt French police and Keenan’s old flame Ruth Vance (Mary Murphy), who is now engaged to Zakon.

After taking control of the clinic, Zakon starts messing with Maxwell’s therapy, erasing the patients’ thoughts and memories and replacing them with plays in which Zakon himself appears as a saviour, thus making people addicted to his treatment – which means more money for him. (and yes, ut turns out that that it is the therapy that has killed the patients, but that is ultimately of no consequence to the proceedings). After digging around, Ruth also becomes aware that something is wrong at the clinic, calls off her engagement and returns to Keenan, which is not taken lightly by Zakon. Zakon kidnaps her and theatens to erase her memories of Keenan. In a last attempt at saving Ruth and the other patients, Keenan and Maxwell infiltrate the clinic and confront Zakon and his henchmen.

Background & Analysis

In 1956 British science fiction author, editor and screenwriter Charles Eric Maine published his fifth novel, Escapement, released in the US as The Man Who Couldn’t Sleep. The film rights were bought by Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy at Anglo-Amalgamated, who had a working relationship with New York-based British independent producer and distributor Richard Gordon, brother of Alex Gordon, who co-founded AIP. Cohen had Maine adapt his own novel into a script and sent it to Gordon, with the hopes that Gordon could secure a star and a distribution deal in the US. Gordon tells Tom Weaver he thought the film had an interesting premise, and envisioned Basil Rathbone, by then a celebrated Hollywood star somewhat on the slide, for the role of villain Zakon. However, Rathbone politely replied that a low-budget SF thriller was not what he had in mind as a comeback film in the UK. The role instead went to British character actor Peter Illing, and Gordon hired American actor Rod Cameron for the lead. Gordon tells Weaver that had Rathbone accepted his offer, the film would have been very different, turning Zakon into the main character.

Despite its French setting, Escapement was filmed entirely in England, with most of the work done at London’s Merton Studios, and some location footage shot outside of London. The budget was around £50,000, or aroud $125,000, in other words a low-budget film on par with what American International Pictures was putting out at the time. Alec Snowden was selected as the nominal producer and Montgomery Tully, a quota quickie workhorse, as director. Dancer and choreographer David Paltenghi is credited as co-director, although assistant or second unit director might have been a more appropriate title, as he only directed the dance-themed dream sequences of the movie.

It’s been a few years since I read the source novel, but I remember being disappointed that Maine wasn’t able to take advantage of his intriguing idea, and that the novel regressed into a hard-boiled crime potboiler. However, the book was certainly better than Maine’s rather weak script adaptation. In the novel, it is Maxwell, the inventor of the “dream machine” that is the protagonist, giving the lead character a personal investment in the story. Maxwell has invented the machine as a solution to his insomnia, and sells it to movie mogul Zakon, before realising that Zakon intends to use it for nefarious means, imprisoning his subjects in an endless sleep in the dream world. The book has a lot more mystery, heavily featuring the enigmatic woman who acts as a bait for important “clients” and draws Maxwell in by seducing him. At one point the book starts blurring the lines between reality and the dream world, and towards the end Maxwell himself is trapped by Zakon in the dream machine. It is not a particularly good novel, and Maine seems unable to develop his ideas further than to resolve them with guns and fistfights. But it is better than his script.

The protagonist of the film, the insurance investigator, is not present in the book, and by making him the lead, Maine robs the central character of any personal stakes in the movie until the very end, when Zakon threatens his gal. This makes for a bloodless proceeding, with most of the film taken up by Keenan moving to an fro different locations, conducting rather uninteresting investigations into stuff that the audience has already figured out. I don’t remember the Nazi connection being a thing in the book, and by 1958, it feels like old hat, especially since it doesn’t have any bearing on the plot, other than pointing out that the villains are evil, a point that is quite readily made by both script and actors without the Nazi detail. The book wasn’t set in France, and I don’t understand why Maine has relocated it, as the setting also doesn’t have any bearing on the plot. The film is smaller, not just in terms of production, but in terms of ideas, than the novel. Granted, bringing a dream world into realisation on a £50,000 budget would have been challenging, but representing people’s innermost dreams and wishes through a lame S/M-themed dance routine shows both a lack of imagination and time. Considering the great idea at heart of the story, everything about the film feels small.

But I want to labour the point that the central idea is a good one, indeed a very good one, and one that feels decades ahead of its time as far as science fiction movies are concerned. At this point in time, SF movies had primarily been concerned with political and social themes, if indeed any themes at all beside rolling out an endless succession of monsters and aliens for the amusement of the teen crowd. In order to find movies that concerned themselves with the mind, our thoughts and dreams, we have to go back to the era of German expressionism, and films like Homunculus (1916, review), The Hands of Orlac (1924, review) or Alraune (1928, review), perhaps with the exception of a few of the horror/SF films of the 30s. The idea, however, of what is essentially virtual reality and the especially the book’s theme of replacing the real world with fictional world, in essence living and feeling the life of someone else through thoughts inserted into your brain, is one that is poignantly relevant as of writing in 2024. The novel speaks of replacing life with unlife, an expression that is oddly omitted from the film, a notion that feels extremely current in an age in which we spend an increasing amount of time plugged in to our computers, smartphones and VR goggles. It is tragic that this theme gets explored so poorly in the movie, brushed aside for a programmatic thriller plot.

It doesn’t help that the central character is completely devoid of personality, or that he is played by Rod Cameron. Built like a tree trunk and gifted with a relatively narrow range of expressions and emotions, Cameron was more at home in westerns and looks lost in this role, in which he has precious little to build a performance upon. Wooden even at the best of times, Cameron here seems to walk through his part with a required minimum of enthusiasm. Peter Illing hasn’t got much more to go on, even if he was a in another class than Cameron as an actor. But as Zakon, he has little more to do than express a one-dimensionally leering evil. Meredith Edwards and Kay Callard are perhaps the only really sympathetic characters as Mr. and Mrs. Maxwell, but unfortunately their screen time is limited. Mary Murphy gives the sprightliest performance of the film, but unfortunately her character is hard to take seriously. That this clearly independent, intelligent, outgoing and beautiful young woman (actress Mary Murphy was 26) would divide her romantic interest between the evil toad of Zakon and the expressionless tree trunk of Keenan (played by Illing, 59 and Cameron, 48) is perhaps the most inexplicable part of the movie. She also has little to go on as far as characterisation, and seems to exist in the movie only as the prerequisite female charm.

Montgomery Tully’s direction is and unable to conjure up much atmosophere, and the film feels cramped by its low budget. Paltenghi’s direction of the dance sequences is no better. I suppose they are meant to represent some sort of secret sexual desires, with half naked men and women moving is vaguely provocative motions, but they look more like aerobic videos than anything stirring up sexual desire. The dream incubators at least look halfway convincing, but the head-piece the patients have to put on is ridiculous, looking like something someone cobbled together at Kindergarten.

Much of the soundtrack is taken up by electronic pulses, beeps and boops. John Simmons is credited as “electronic music consultant”, probably so Anglo-Amalgamated didn’t have to pay him a composer’s fee (at the time, for example, the composers of BBC’s groundbreaking electronic music were officially “technicians” and didn’t get paid for their compositions). Musical director Richard Taylor has combined Simmons’ electronic score with stock music by Trevor Duncan. Using a largely electronic score was certainly novel at the time, few films other than Forbidden Planet (1956, review) had taken that route. Unfortunately Simmons’ random-seeming beeps and boops can’t hold a candle to Bebe and Louis Barron’s groundbreaking 1956 score. Simmons’ work here is not musical enough to really pass as a score, but rather feel like randomly inserted sound effects that do little to stir up emotions or support the story.

Escapement is not the worst movie I have reviewed by a long stretch: it is competently made, but simply quite boring and programmatic. Feels like a lost opportunity.

Reception & Legacy

Escapement premiered in the UK in March, 1958. In the US, Richard Gordon was able to get it distributed by Columbia, and paired it up with Womaneater (review). In the UK it was later re-released as The Dream Machine. Gordon says that he came up with the title The Electronic Monster for the US release. However, it didn’t get a wide US release before 1960, when Columbia re-released it as a bottom bill with 12 to the Moon.

British The Monthly Film Bulletin gave Escapement a 2/4 rating writing: “the theme gives this science fiction melodrama a certain originality”. Variety’s London correspondent called it a “fair programmer” with an “ingenious idea”. However, reviewer Chris continued: “The promised thrills never fully materialize, nevertheless, a bunch of very able actors manage to keep interest alive with a straightforward script that would have benefited from a few highlights.”

Upon its 1960 US release, the Motion Picture Exhibitor noted that “the title may have some audiences thinking they are about to see a science fiction film”. One does wonder what the Motion Picture Exhibitor thought a science fiction film was. The magazine stated about the movie: “Fair acting, unbelievable yarn that stretches the imagination and interest, and average direction and production are to be found in this unpleasant entry”. The Film Bulletin called The Electronic Monster “strictly standard laboratory hocus-pocus”. Harrison’s Reports said: “Scarcely departing from the ordinary formula, this grim science-fiction programmer just manages to hold the viewer’s interest”.

Today the film has a, perhaps even surprisingly high, audience rating of 4.6/10 on IMDb, albeit from only 200 votes, and not enough votes for a Letterboxd or Rotten Tomatoes consensus, speaking to its obscurity.

Richard Scheib at Moria gives the movie a good old thrashing, with a 1/5 star rating: “the way the idea as handled here goes nowhere. The script is very talky. Everything is directed in a doggedly literal fashion […]. There is little action – most of the film takes place in drearily ordinary offices and the two punch-ups we get are so unconvincing that one spends more time laughing. […] The film offers up stolid carved-in-granite Rod Cameron as the hero of the piece and he moves through the film like the proverbial brick shithouse in both build and locution.”

Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings says: “There are some intriguing ideas in this SF thriller; however, the movie itself is hackneyed, incredibly talky, and quite dull”. Mark David Welsh calls Escapement a “limp, and rather dull, science fiction picture”. He continues to say that Tully “imbues proceedings with all the urgency of a forgotten TV episode, and events proceed, and conclude, in exactly the way an 8-year old would predict after watching the first five minutes”.

Cast & Crew

The name of screenwriter Charles Eric Maine was one of the nome de plumes of David McIlwane. Maine was the name he predominantly used for writing science fiction, and we have encountered him before on this blog, as the screenwriter for Spaceways (1955, review) and Timeslip (1955, review) two other films in which the science fiction element is underplayed to make room for more traditional noir elements. Timeslip had actually been made as a British TV movie in 1953, to cash in on the hype of the groundbreaking TV show The Quatermass Experiment (review).

Timeslip was novelised in 1957 as The Isotope Man, giving rise to the misconception that the film was based on a book. The novel became the first entry into Maine’s only book series, about reporter Mike Delaney. Escapement was turned into a film with the same name in 1958, and his last sci-fi novel The Mind of Mr. Soames (1961) got a film treatment with the same title in 1970. Other noteworthy sci-fi books were Timeliners (1955) High Vacuum (1956), World Without Men (1958) and Calculated Risk (1960).

Escapement is typical of Maine’s writing, inasmuch as it leans heavily on the thriller plot and sort of tip-toes over the science. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction writes about Maine that his SF novels have a ”a disinclination to argue too closely scientific pinnings that are often shaky”. Damon Knight in his book In Search of Wonder agrees, points out that Maine seems to lack knowledge in the most basic scientific facts. He writes that ”Maine’s physics is bad, his chemistry worse /…/ The gross errors in [High Vacuum] are in the area of common knowledge (as if a Western hero should saddle up a pueblo and ride off down the cojone): any one of them could have been corrected by ten minutes with a dictionary or an encyclopedia.”

The director of Escapement (1958), Montgomery Tully, was an Irish-born writer and director of primarily undistinguished low-budget movies. He is best known for directing Murder in Reverse? (1945), an early role for Sean Connery, and his two last films, the science fiction clunkers The Terrornauts (1967) and Battle Beneath the Earth (1967).

Canadian-born Rod Cameron dreamed of becoming a mountie as a child, but instead embarked on an acting career, first trying his luck on stage, and when his career didn’t progress, moved to the West Coast to try and break into the movies in the late 30s. The rough-hewn, 6’4 (193 cm) actor found it slow going, as he primarily worked as a stand-in and insignificant bit-parts. However, in the early forties he started receiving supporting roles in westerns, and got big break in 1943, when he starred in two Republic serials, one western and one African adventure/spy yarn. From there he went to Universal, where he was cast as the lead in numerous low-budget westerns. With his movie career on the slide, he turned to TV in the 50s, and starred in three minor TV series. Despite the diminishing quality of his roles, he kept omn acting until the mid-70s.

Cameron’s American co-star in Escapement (1958) was Mary Murphy, who was signed by Paramount at the age of 20 in 1951. One of her early roles was a bit-part as a student in When Worlds Collide (1951, review). She quickly worked her way up to leading lady status, with her first starring role in the ill-received, star-studded showbiz drama Main Street to Broadway (1953). However, she got noticed in her next role, playing the love interest of Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953). However, the film didn’t lead to more prestigious work, even if Murphy continued in leading lady roles in middle-of-the-road movies like Beachhead (1954) and A Man Alone (1955), and had a supporting role in the A-movie The Desperate Hours (1955). However, in the mid-50s, the quality of her roles diminished, as illustrated by her involvement in Escapement, and she sequed into television. She co-starred in the short-lived Investigators (1961) and appeared as a guest star in numerous other shows. Murphy took a 4-year hiatus from acting in 1968, but returned in 1972 when she was offered a role in Sam Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner, but after that it was strictly TV fare for her until she retired for good in 1975.

Peter Illing was a German-born actor of German and Turkish descent, who moved to the UK with the outbreak of WWII. Due to his accent and slightly “exotic” features, he specialised in playing Nazis and foreign roles. Other German expats, Carl Duering and Carl Jaffe had similar career trajectories. Duering had a slightly more visible career. He is especially remembered for his turn as the evil Dr. Brodsky in A Clockwork Orange (1971), for playing the detective in the horror movie Possession (1981) and for his role as Hassan Jena in Arabesque (1966). He also had a small role in the SF thriller The Boys from Brazil (1978). Carl Jaffe had a tendency to show up as a doctor or scientist, and did in Timeslip (1955), Satellite in the Sky (1956, review) Escapement (1958, in an unusually large role) and Battle Beneath the Earth (1967).

Alan Gifford, here in a bit-part, appears on a video phone screen in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) as Gary Lockwood’s father. He also appeared in Escapement (1958), The Road to Hong Kong (1962) and Phase IV (1974).

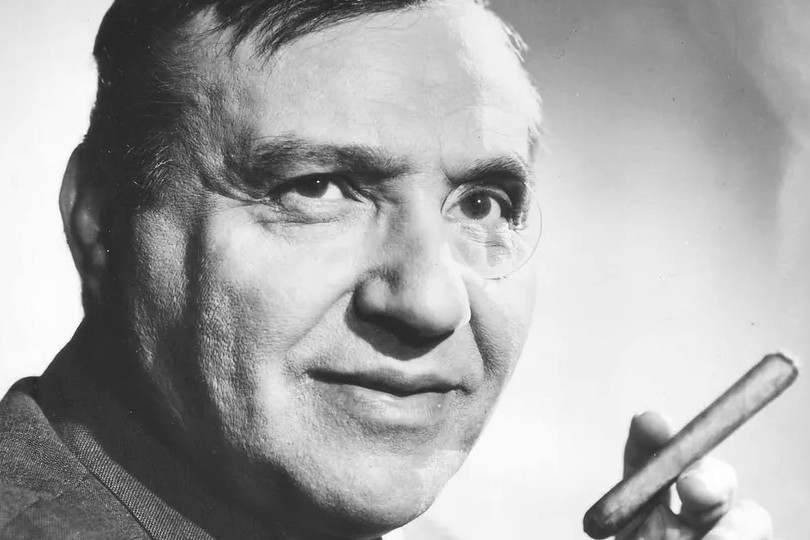

Executive producer Richard Gordon was the brother of slightly better known Alex Gordon. The brother both became interested in the movies from a young age, and relocated for greener pastures in New York in the 40s. Alex moved to Los Angeles, where he befriended people likeBela Lugosiand Ed Wood, and became one of the original producers of American International Pictures. Richard stayed in New York, where he set up his own company Gordon Films, importing and distributing British and international films to the US. He gradually became more film production, and ended up being the de facto producer on many films from the mid-50s onward, even if he was often uncredited for the first decade of his producing career. A friend of both horror and science fiction, he produced Escapement (1958), Fiend Without a Face (1958, review), First Man Into Space (1959, review), The Projected Man (1966), Island of Terror (1966), Horror Hospital (1973) and Inseminoid (1981).

Janne Wass

Escapement. 1958, UK. Directed by Montgomery Tully. Written by Charles Eric Maine, J. McLaren Ross. Based on the novel Escapement by Charles Eric Maine. Starring: Rod Cameron, Mary Murphy, Meredith Edwards, Peter Illing, Carl Jaffe, Kay Kallard, Carl Duering, Roberta Huby, Felix Felton, Larry Cross, Jacques Cey, Alan Gifford. Assistant director: David Paltenghi. Cinematography: Bert Mason. Editing: Geoffrey Muller. Art direction: C. Wilfred Arnold. Makeup: Jack Craig. Sound editor: Derek Holding. Musical director: Richard Taylor. Electronic music: John Simmons. Produced by Alec Snowden for Anglo-Guild Productions.

Leave a comment