Peter Cushing shines once again in the title role of Hammer’s 1958 sequel. Jimmy Sangster’s script puts an interesting class angle on the story, and despite its meandering plot and lack of focus, it remains one of Hammer’s best. 7/10

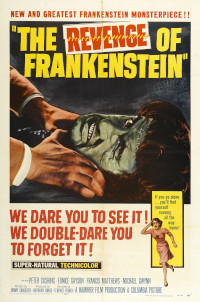

The Revenge of Frankenstein. 1958, UK. Directed by Terence Fisher. Written by Jimmy Sangster, Hurford James, George Baxt. Starring: Peter Cushing, Michael Gwynn, Francis Matthews, Richard Wordsworth, Eunice Gayson, Oscar Quitak. Produced by Anthony Hinds.

Baron Victor Frankenstein (Peter Cushing) has been sentenced to death for creating a murderous monster, and beheaded at the guillotine. The next night, two graverobbers (Lionel Jeffries, Michael Ripper) dig up his grave only to discover that it contains not Frankenstein, but the priest who presided over his execution (Alex Galler). Turns out, Frankenstein’s assistant Karl (Oscar Quitak) has schemed with the executioner to save the Baron. Three years later Frankenstein has set himself up as the most successful physician in an unnamed Central-European town, under the name of Dr. Victor Stein. Here, he makes his money by treating the upper-class, whose payments help finance his pro bono hospital for the poor. But of course, we know that, despite appearances, Baron Frankenstein is still up to his same old tricks.

Hammer Films’ The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) picks up immediately after the events in the studio’s genre-defining The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review). The old gang returns for this sequel, with Anthony Hinds as producer, Terence Fisher as director, Jimmy Sangster as writer and, of course, Peter Cushing as the infamous doctor. Once again, Hammer shot in colour in and around the famous Bray Studios, creating a sequel worthy of its renowned original.

In the small unnamed town, let’s call it Hammertown, the influential medical councel is upset. Three years ago, this Dr. Stein rode into town with no credentials or recommendations, and set up practice. Now he is winning over the town’s wealthy clients, reducing the income of the rest of the practitioners. The councel sends over a delegation to Stein’s clinic for the poor, to put him in his place. There, among the filthy criminals and beggars, they have little luck. But one of the delegate members, young Dr. Kleve (Francis Matthews) recognises Stein as Baron Frankenstein. Instead of blowing the whistle on him, he seeks out Frankenstein and asks for the opportunity to become his apprentice, as he seeks to learn Frankenstein’s secrets. And boy, does he have secrets to show.

Of course, old Victor is about to reprise his experiment, this time without a damaged brain. The body is already set to go, and only needs a brain. The brain is also in waiting, as Frankenstein intends to use the brain of his crippled assistant Karl — a bright, intelligent fellow who is all too eager to get a new, handsome and healthy body. And since Karl can’t assist in the operation, Kleve’s help is much welcomed. The operation goes without a hitch, and Karl in his new body (played by Michael Gwynn) is strapped to a bed, as Frankenstein explains that the brain needs time to heal and get adjusted to the new body. If the process is disturbed, he explains in a moment of obvious foreshadowing, the brain may regress into primal barbasism.

So that he can be regularly looked after, Karl is moved to a private room at the clinic for the poor, but the resident patient/caretaker (Richard Wordsworth, the character is unnamed in the film, so let’s call him Richard) spies on Frankenstein and Kleve as they carry him in. Looking after Karl, Kleve unwisely tells Karl that Frankenstein is going to parade him in front of the world’s medical and scientific elite as proof of Frankenstein’s genius. But Karl, having been stared at all of his life because of his disability, revolts against this ironic fate. Meanwhile, Richard tells well-meaning but naive upper-class lady Margaret (Eunice Gayson), who does charity work at the clinic, about the “secret patient”. Margaret sneaks into Karl’s room, and is stricken by the soft-spoken patient. Karl cleverly complains that his straps are too tight, and Margaret loosens them for him. As soon as Margaret is out the door, Karl frees himself and sneaks out through a window. On his way out, he sneaks into Frankenstein’s lab in order to dispose of his old body. But he is caught by the janitor, who mistakes him for a burglar, and smashes a chair over his head and not-yet-healed brain. However, Karl manages to escape, and seeks out Margaret. Margaret promises to help him, but in secret travels into town to fetch Frankenstein. But when they return, Karl has disappeared.

Meanwhile, trouble is brewing. The medical council has been able to put two and two together and deduced that Dr. Stein is indeed Dr. Frankenstein. Of course they have no proof. But their cause is helped by Karl, who quickly starts to regress into his old crippled self, and worse than that: into a drooling, mindless animal. Karl attacks and kills a girl in a park, and then crashes an upper-class soirée which Frankenstein, Kleve and Margaret attend. When he sees Frankenstein, he cries: “Dr. Frankenstein, help me!” With the cat out of the bag, word quickly spreads from the upper class to the lower classes. The patients at Frankenstein’s clinic realise that he has been using them for raw material for his experiments, and attack him, beating him almost to death, before he is saved by Dr. Kleve.

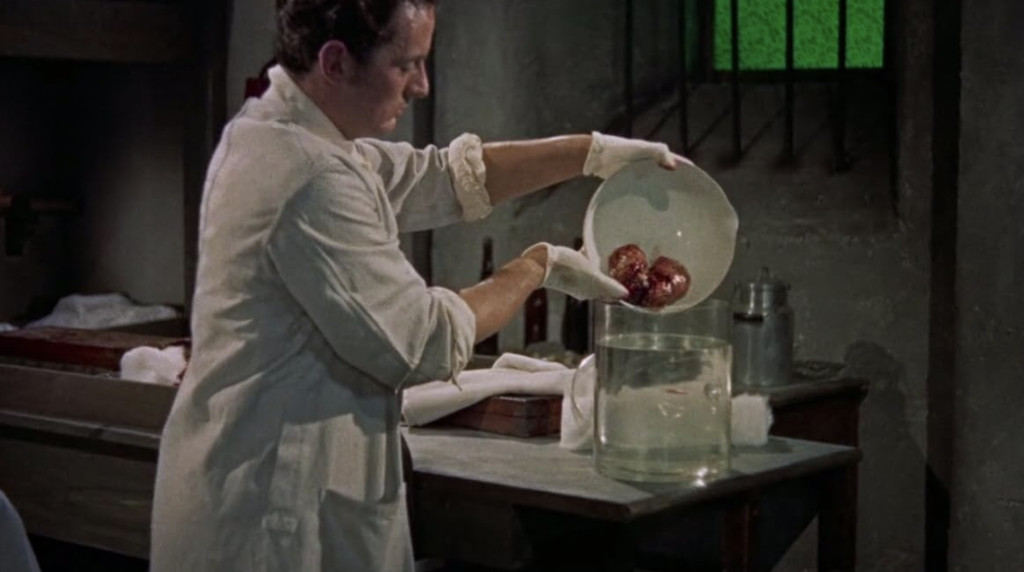

Kleve tries to patch him up, but Frankenstein tells him it is of no use. But old Victor is prepared. He has put together a clone of himself which rests in a glass container, and has instructed Kleve to put his brain into the new clone, should anything happen to him. But with the police on the way to arrest Frankenstein, will he be able to perform the operation in time?

Background & Analysis

The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) came about after small British studio Hammer Films’ president James Carreras had visited Hollywood and made a three-picture distribution deal with Columbia, which included The Camp on Blood Island, The Snorkel and The Revenge of Frankenstein (then still called “Blood of Frankenstein”). Back in London, he presented screenwriter Jimmy Sangster with the poster for the movie and asked him to write the corresponding film “within an impossibly short space of time”.

Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review) had sent shockwaves across the cinematic world with its stylish direction, magnificent acting and in particular, its garish, highlighted blood and gore (even if the film is, in fact, surprisingly un-gory when watched in retrospect). A sequel seemed inevitable, as seemed the fact that Hammer would have to revive Universal’s other great monster, Dracula. Even Universal eventually saw which way the wind was blowing and handed over the remake rights of all its classic monster movies to Hammer, rightly judging that these new, hip horror films would inevitabely stir interest in the old films as well. So Hammer went along and shot The Revenge of Frankenstein back-to-back with Dracula (1958), with much of the same cast, crew and even costumes.

Christopher Lee, who played the Creature in Hammer’s first Frankenstein film, did not return in Revenge, however, he took his place as a bona fide movie star and horror icon as Dracula. Peter Cushing, on the other hand, returned to the role of Dr. Frankenstein, cementing the path Jimmy Sangster and director Terence Fisher chose in the first film, putting the creator and not the Creature in the centre of the movies. One can argue that The Revenge of Frankenstein doesn’t even have a monster at all. Karl, despite the fact that his animalistic instincts cause him to kill a girl in a park, is really a victim all the way through — and not even a victim of Frankenstein’s folly, but of an over-enthusiastic caretaker who mistakes him for a burglar.

Speaking of Dr. Frankenstein, it is a very different Frankenstein we meet in this movie, at least on the surface. However, the way the script is written leaves his motives slightly ambiguous. Nevertheless, the contrast between the old and the new Frankenstein is striking. In the first movie, Victor Frankenstein was a ruthless, scheming, singularly driven monomaniac who happily killed an old professor without blinking an eye to get a brain for his creature, neglecting his fiancée and friends, morals and duty for his work. Hete, in contrast, we meet a Frankenstein who is, in lack of a better word, almost jolly. He seems to have not only a great respect for, but also genuine sympathy and a desire to help his assistant Karl — one might even call it a sort of love for him. He also seems to be happily providing his services to the poor and needy, perhaps seeing in them a sort of companionship – one outcast to the other. Instead of robbing graveyards and murdering for bodyparts, Frankenstein new seems to use only such parts that would have to be amputated anyway, and are thus useless to their owners.

On the other hand, the film provides us with just enough ambiguity to doubt the doctor’s good intentions. The fact alone that Frankenstein wisely hides his true intentions from Karl gives us a hint that this “new” Frankenstein is not the humanitarian he sets out to be, still caring most about fulfilling his own goals, caring little for the consequences for those around him. We are told that Frankenstein only uses “waste material”, but we here only from his own mouth, and his patients from the gutters seem to know by instinct that this Dr. Stein is up to no good, and is pilfering their bodyparts like some sort of Frankenstein. Even if said in jest, there’s a feeling that a crook knows a crook by his feathers.

The Revenge of Frankenstein has both its defenders and its detractors, with some claiming it to be the best in the Hammer Frankenstein cycle, some one of the lesser entries. Both sides have valid points, and in the end it is up to personal preferences. If you are looking for an all-out horror movie, then The Revenge of Frankenstein is a bit of a dud. In fact, it is more melodrama than horror. Jimmy Sangster has written a movie clearly aimed at adults, and cut back on the putty-faced monster, the “look-at-me” gore shots and the blood splatters. The goriest shots are of Kleve or Frankenstein pouring a jelly brain into a vat, and that wasn’t even particularly gory in the 50s.

Jimmy Sangster’s screenplay is witty, sharp, and contains some brilliant dialogue throughout, laced with his dry humour, which always seemed like it was tailor-made for Peter Cushing. It has fairly interesting characters; of course Frankenstein himself, but also the unnamed patient who acts as a sort of cleaner/assistant at the clinic, as well as Karl. Although the film itself isn’t fast-paced in the sense that there are things happening all the time (in fact very little actually happens), Sangster’s script, Fisher’s direction and Cushing’s acting drive the film forward at a snappy pace. It is clear Hammer has a bigger budget than for The Curse of Frankenstein, which practically took place in two rooms. Despite its small-scale, contained plot, Revenge feels a lot bigger than its predecessor. This is all relative of course: the movie was still filmed in Hammer’s small Bray studio with environments. Sets and costumes were reused from Dracula, which wrapped three days before filming began on Revenge.

Where The Revenge of Frankenstein revels is in its character study of Victor Frankenstein. Tim Brayton writes at Alternate Ending: “When, ignorant of all hypocrisy, he snaps at Kleve for lacking a sense of human behavior (it’s especially hypocritical in context); when he cheerfully saws off a perfectly healthy arm on the grounds that the poor don’t deserve it, or stares at a powerfully rich mother of an eligible young lady with all-encompassing indifference, on the grounds that the rich are assholes; when he unhurriedly gets ready to die in the hope of escaping an angry mob; Frankenstein is something grandly intelligent and terrifyingly inhuman, played with just the right amount of dry amusement by Cushing that it’s almost impossible not to be suckered into liking the bastard, despite the copious evidence that we shouldn’t.”

Jimmy Sangster wryly inserts a class commentary wholly absent from Mary Shelley’s original novel (indeed, Shelley and her upper-class Romantic circle spent very few lines of poetry to exploring the divide between themselves and the “great unwashed”). Like in The Curse of Frankenstein, Victor has little time for the etiquette and rituals of the nobility, seeing the noble socialites as air-headed sheep going through meaningless motions. However, he plays the game as far as is required for him to keep up appearances, and crucially: as far as it gains him. In Revenge, he even seems to take a certain perverse pleasure in mimicking the posh vacants around him. But he likewise seems to have little respect for the lower classes, liking them to the dogs and apes he conducts his experiments on. Frankenstein’s mind is focused like a laser beam on his – as he sees it – clinically detached work. While he, in Curse, still held pretenses that he was doing his experiments for the good of mankind, in Revenge he seems to have dropped even this self-deceit and now sees his impending success as his revenge on the scientific society which cast him out.

Frankenstein adhers to no class or social group – even as a scientist he fathoms himself singularly exceptional, and thus above reproach. But, interestingly, the script seems to hint at a deeply buried humanity and a longing for companionship. In both Hammer’s first Frankenstein movies, Victor seeks out assistants that become more than just colleagues. In the first movie, Paul Krempe is first Victor’s mentor and a substitute father figure, who later becomes a dear friend. The real tragecy in Curse is Krempe’s betrayal and abandonment of Frankenstein. In the second film, Hans Kleve takes Krempe’s place as both assistant and friend – in the end, Victor trusts Kleve enough to put own life – and brains – in his hands. Kleve, on the other hand, also seems to lack the moral impediments that destroyed Victor’s relationship with Krempe. At the end of the film, we see that Kleve has abandoned continental Europe and travelled with Victor to London, almost like a companion, rather than just an assistant. A queer reading of Curse and Revenge is interesting: Victor seems to be much more interested in the male companionship of his assistants, than in the beatiful women that surround him in both movies. Indeed, had Cushing’s Victor Frankenstein been introduced today, he would certainly have set off quite a few gaydars; from his exquisite, delicate manners to his appreciation of bright and extravagant clothes (he is quite the dandy), Cushing’s Frankenstein could be something of a gay icon. Quite unintentionally, I am sure.

One problem with Sangster’s hastily written script is that it remains a character study that doesn’t go anywhere. The circumstances around Frankenstein change, but Frankenstein himself doesn’t. Victor’s convictions, choices or morals are never challenged, unlike in The Curse of Frankenstein, where his actions have personal impact. This makes the film feel oddly pointless, just another snapshot from the life of Victor Frankenstein. The really interesting character to follow would have been Karl, and it’s a fun thought experiment to make him the real protagonist. Alas, we spend too little time with Karl in this movie for this to become a reality. The exploration of Karl up-cycling himself from wretched hunchback to a perfect specimen of manhood, paraded through the upper echelons of society, and what this journey does to him, would have been, I think, the basis of a splendid movie. Not a horror movie perhaps. But on the other hand, The Revenge of Frankenstein isn’t really a horror movie as it stands.

We feel for Karl, but he remains too much of a background figure for us the audience to really care. We never get to know him, as the film follows Victor most of the time. For Frankenstein himself, the only stakes is the risk that he is found out for who he really is and what he is doing in his basement. His “revenge” is too abstract and intellectual for the audience to care about (he is doing just fine in his new life, it’s not like he’s been forced to live in the gutters, unlike the wretches he is tending to). In a way, Frankenstein is going through the motions once again, but this time without the wonder and horror of the first movie.

All in all, the script feels hastily cobbled together without any deeper thought put into it. Sangster plays with class themes, without really getting down and dirty with them. The seeming change in Frankenstein’s personality (if indeed there has been one, or of it is all just an act) is never explored. We know that his rejection and near-death experience has irked him, and that he now wants to prove his nay-sayers wrong. But his quest to create life feels oddly dispassionate, like he was trying to develop a new kind of car battery. Long stretches of the film feel like padding. Much time is spent with Richard Wordsworth’s unnamed “up patient”, as he is credited, and it is a delicious character, but one that is wholly inconsequential for the plot. The same goes for Eunice Gayson’s Margaret, only in the movie because the PR campaign requires a beautiful woman. There’s not even a romance plot between Margaret and Kleve (or Karl). Margaret’s only function in the film is to loosen Karl’s straps, so he can escape, and one can think of numerous other ways in which he could have made his getaway.

The horror element that raises most eyebrows is the notion that Karl “reverts” to primitive cannibalism if his brain is injured during the healing process. Scientifically, this is of course ridiculous hokum, as if cannibalism would be some kind of Darwinian “state of origin” to which a human brain could magically “revert”. But even more disappointing is that Sangster never does anything with this notion – it is hardly even mentioned after the film has established that Karl, like the chimpanzee munching on a fellow monkey, might become a cannibal. It feels as if Sangster realised there wasn’t enough shock value in his script and added the cannibalism schtick mereley to outrage the prudish British censors and ensure the film’s X rating.

While the plot is fairly straightforward, it is difficult to gauge what the film is really about, in terms of themes. Granted, this was a major flaw in Sangster’s script for The Curse of Frankenstein as well. There are hints at themes here and there, but none that are carried through. The confrontations seem more like technicalities than clashes of wills, morals or emotions. For a film so steeped in the gory reputation of the Hammer horrors, The Revenge of Frankenstein is oddly bloodless, in all senses of the word.

One reason for the difficulty of wringing much thematical analysis from the movie is that it lets Victor Frankenstein off the hook so easily. If we are to take it at surface value, Victor really does nothing wrong – he helps a wretched man to a new body, constructed through no foul play and doesn’t hurt anyone in the process. That things go pear-shapes is a combination of Kleve’s big mouth, Margaret’s gullability and a drunken, over-zealous caretaker. Anyway, this trope of Frankenstein failing because of a damaged brain was old hat even in 1958, a trope created for Universal’s 1931 movie (review), and repeated several times since, even by Hammer themselves in Curse. This trope sidesteps the tragedy of the book, and dissolves Frankenstein’s responsibility for his creation in a way that pulls the rug from under any interesting philosophical and moral notions, leaving little more than the “things that man shouldn’t dabble in” notion to be played with.

This said, The Revenge of Frankenstein is by no means a bad film. It’s engaging, snappily paced, competently directed and superbly acted, in particular regarding Peter Cushing. The shooting schedule seems to have been quick, since director Terence Fisher and cinematographer Jack Asher don’t show quite the same energy and inventiveness they showed in Curse, or in particular in Dracula. Much of the blocking and framing is static, but Fisher is a steady hand at the helm, and there are standout moments, such as the “Dr. Frankenstein, help me!” scene.

The “monster” will come off differently depending on your expectations and preferences. If you’re hoping for another christopherlee-esque creation with bits and pieces falling off of him while he relentlessly kidnaps and murders, you will be disappointed. I, on the other hand, was disappointed when Karl turned into a shaggy apeman frothing at the mouth, more than anything inspired by Fredric March’s Jekyll (review). Also, the idea that he would have grown a hump on his back and regained his paralysis in his one arm and leg is ridiculous and an affront to an otherwise intelligent script. Michael Gwynn portrays the dual part sensitively and with conviction – even if he was a somewhat mundane actor. Philip Leakey’s makeup is convincing, if not particularly memorable.

However, I find myself wanting to see more of the actor playing Karl before he moves into a new body, the relatively unknown Oscar Quitak. Quitak gives a very memorable and gripping performance as the soft-spoken, kind-hearted hunchback. Another relative unknown was Francis Matthews as Hans Kleve. Matthews has good rapport with Cushing, but remains in his shadow. He is the film’s “straight man”, and does what is required without standing out in any way. Richard Wordsworth hams it up deliciously as the “up patient”, and remains the most memorable character in the film beside Frankenstein himself. Proof of Wordsworth’s talents were given in Hammer’s The Quatermass Xperiment (1954, review), in which he played the “monster”. Gorgeous Eunice Gayson does what she can with her inconsequential role. Lionel Jeffries and Hammer legend Michael Ripper have a ball as the goofy grave robbers who dig up Frankenstein’s grave in the beginning of the movie, only to find the body of the priest.

But like Curse, The Revenge of Frankenstein is Peter Cushing’s film. Despite the changes to Frankenstein’s mood, Cushing slips into the role like it’s a well-worn slipper, dissecting it with the precision of his character, while making it all seem absolutely natural. In my review of Curse, I wrote: “Cushing was perhaps best as characters that seemed to cut through obstacles and considerations like a knife as sharp as the actor’s nose. From the get-go, Victor Frankenstein seems to be completely assured of his potential and single-mindedly driven to scientific greatness. This is a man who has devoted his life to uncovering the secrets of the universe and deems all else in life secondary. While he does confront and kill the creature when it attacks Elizabeth, there is no hint that he would have any deeper feelings for her, and seems to treat his marriage mostly as a social facade. His calculating coldness and disregard of human life is clear in the scene where he mockingly dismisses Justine’s anger over him breaking his vows to marry her, and throws her to the monster as if she was simply a piece of meat for a tiger at a zoo.”

The same goes for Revenge, although now Cushing brings in a further sense of ease and coolness to the character. The scene in which Frankenstein is half interrogated, half blackmailed, by Kleve, who has found out his identity, while Frankenstein is coolly dissecting his chicken dinner is masterly. Throughout the film, Cushing is precise and deliberate in every movement, every look, every gesture. Even when cornered by an angry mob and getting ready to be torn to pieces, his Frankenstein never loses his composure, calmly awaiting the onslaught, as if he had planned it all along. And just a detail: Cushing is the only actor in the film who pronounces “Kleve” correctly as [kleːvə], rather than [kleɪv], as Matthews introduces himself. Just goes to show how meticulous Cushing was in his preparation.

According to Bryan Senn’s book Twice the Thrills! Twice the Chills!, co-star Francis Matthews, the set of The Revenge of Frankenstein was a happy and playful one, with the atmosphere of glee and joy emanating from Peter Cushing. Cushing, 45 at the time and at the pinnacle of his art, had been given a tremendous career boost thanks to Hammer’s horror movies (much like friend and co-star Lee) at an age when many actors start to see their hopes of stardom fading. Furthermore, like Lee, Cushing was also invested in the horror and science fiction genre – he had personally requested the chance to play Dr. Frankenstein when he heard that Hammer was making an adaptation. According to Matthews, “My impression of Peter Cushing was of a happy, contented and professionally fulfilled man. He made me feel at home instantly.” There are many anecdotes testifying to Cushing being a kind, considerate, welcoming, charming, playful and mischieavous man, often playing practical jokes on set and fooling about, sending the cast and crew into bouts of laughter. Says Matthews: “His laughter was a tonic that made the working days fly by”.

At heart, The Revenge of Frankenstein is a cheap B-movie, disguised by Jimmy Sangster’s eloquent and sometimes even intelligent dialogue, the lush Eastmancolor and Peter Cushing’s magnificent prescence. In some areas, it trumps The Curse of Frankenstein, in particular when it comes to sets and airiness. It also improves on Curse’s awkward structure, with the monster being assembled twice, causing a huge sag in the middle of the film. For Curse, Sangster had a beginning and an end, but didn’t quite know how to fill out the middle in order to achieve and 90-minute movie. Nevertheless, Curse had a more clear-cut drama and the story had more at stake. And despite its flaws, Curse felt absolutely fresh. In Revenge, Fisher and Sangster no longer have the advantage of novelty, and in many ways, it feels as if Revenge retreads old ground. Sangster does his best to shake things up, but in the end it’s the same old story of Frankenstein making his monster and being tripped up by other people’s mistakes. Apparently, Hammer felt the same way, as it would take another six years for the studio to revisit the franchise with The Evil of Frankenstein (1964).

Reception & Legacy

The Revenge of Frankenstein premiered in June, 1958, in the United States, where it was paired with another British horror, Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (retitled Curse of the Demon in the States), and in August in the UK.

In Britain, The Monthly Film Bulletin, as usual with Hammer, disliked the film, giving it its lowest rating. The magazine cited a “contrived plot and notable lack of pace and imagination” and a “crude and pedestrian handling of the little legitimate horror left”. Jack Moffitt at the Hollywood Reporter was likewise critical, citing a “disjointed tale”, and opined that the scipt lacked “one of the basic essentials for a good horror tale – an anxiety for the characters being menaced”.

The American trade press was generally positive, with Variety calling it “a high grade horror film”, and The Film Bulletin labeling it “a good Victorian thriller. However, opinions were divided over whether the film was scary or not. The Film Bulletin noted that “For sheer narrative construction, this is good stuff”, but noted that the “humanization” of the monster deprived the movie of its shock and horror value: “we understand the ghoul and can’t be frightened”. At Harrison’s Reports, their horror critic apparently had a rather weak stomach, outright lambasting the competing 1958 SF/horror outing Fiend Without a Face (review) for its bubbling gore. Contrary to Bulletin, Harrison’s Reports warned readers that “bright red blood […] drips all over the place”. The critic continued: “It is gory stuff, with enough chills and shudders to take care of a dozen normal horror films”. Nonetheless, the magazine called The Revenge of Frankenstein “a first-rate picture of its kind”.

Richard Gertner at Motion Picture Daily gave the movie a positively glowing review, rating it as even better than The Curse of Frankenstein. Gertner anticipated that Dr. Frankenstein would return in a third film, and wrote that he would be “most welcome”. He called it “a horror picture turned out with creative skill and imagination”, and noted that blood and gore look “13 times as gory” in colour than in black-and-white: “The Hammers have demolished once and for all the theory that horror films should always be in black and white”.

Today The Revenge of Frankenstein has a 6.7/10 rating on IMDb, based on around 6,000 votes, a 3.4/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on around 5,600 votes and a 6.7/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes.

The Revenge of Frankenstein has a good reputation. William Thomas at Empire gives it 4/5 stars, calling it “one of the best of the Hammer series”, while Time Out singles out Peter Cushing’s performance in the film as “one of his best”. John Slater-Williams at the British Film Institute includes the movie among the 10 best horror sequels, writing: “The Revenge of Frankenstein feels like the true trendsetter for the studio’s boundary-pushing in terms of on-screen obscenity, gallows humour and just the right amount of deranged plotting.”

Richard Scheib at Moria gives the film 4/5 stars, opining that it represents “one of the rare occasions when a sequel proves as equally inventive as the original”. In a gushing review at Alternate Ending, Tim Brayton writes: ” The Revenge of Frankenstein is a brilliant sequel, one of the most sophisticated and intelligent follow-ups to a horror classic that has ever been put to film”.

The movie doesn’t really get bad reviews from serious critics and film historians, however, many are more reserved in their praise. For example, Denis Meikle in his definitive book on Hammer’s history, A History of Horror: The Rise and Fall of the House of Hammer, calls it “often flat and theatrical”, and notes that “In its slower mid-section, Fisher seems to lose his grip on the material altogether for a time, engaging in longueurs, a penchant for eccentricities of charactarization at the expense of pace, and a lethargy of composition that produces the familiar sequence of static tableaux whose sole point of interest becomes the décor in which they are framed”. Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant notes that “Frankly, Sangster isn’t the best screenwriter in horror film history. He wastes time and energy on characters that don’t pan out, and his third act throws logic for a loop.” Bill Warren in Keep Watching the Skies! chooses a diplomatic approach: “while interesting and graced with Peter Cushing’s fine performance, Revenge is a mixed bag of horrors. While it is neither as good as its supporters claim nor as bad as its detractors would have it, plenty of evidence in the film supports both views.”

While the ending, with Frankenstein showing up in London, would have invited a direct sequel, no such thing was forthcoming. As stated, with the American success of Hammer’s two Frankenstein films, and Dracula, Universal turned over the remake rights of their old horror films to Hammer. Suddenly, Hammer had lots of new toys to play with, and resurrected the Wolf Man, the Mummy, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, as well as the Old Dark House. It was not until 1964 that Evil of Frankenstein was released, and it was not really a sequel, as it didn’t acknowledge the two earlier movies. In the future, Dr. Frankenstein would return in a number of unrelated adventures, as Robin Bailes puts it at Dark Corners, a sort of “James Bond of horror movies”.

Cast & Crew

Born in 1904, director Terence Fisher was a late bloomer. Switching the life of a sailor for the movie business, he started as an editor in the 30s, before he graduated to direction in 1948. He made both A movies for Gainsborough and supporting films for smaller companies. In 1951 he did his first film for Hammer, who liked him, and he became a staple at the studio. Fisher disliked science fiction, but nonetheless made three early SF entries for Hammer, Stolen Face (1952, review), Four-Sided Triangle (1953, review) and Spaceways (1953, review). During the 50’s Fisher was a respected workhorse, but had no great name recognition, nor was he particularly defined by any specific style or genre. With the success of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review), it was Val Guest who had become the star director of Hammer. A probable reason as to why Guest didn’t direct The Curse of Frankenstein (1957, review) might be that he was busy with Quatermass 2 (1957, review).

As it so happened, Fisher loved making horror movies, and with the success of The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula, Hammer came to love Fisher, even if it was a love-hate relationship. He didn’t get along with James Carreras, the big boss at Hammer, and was at one point fired from the studio after a costly flop in the early 60’s.

Troy Howarth writes in an unusually good IMDb bio: “At the center of Fisher’s work is a fascinating moral dilemma: the seductive appeal of evil vs. the overzealous, frequently close-minded representatives of good. The consistency of theme in Fisher’s work, coupled with a distinctive style achieved through precise framing and a dynamic editing style, refutes the idea that he was merely a hack for hire, while lending his films a recognizable signature.” These themes, coupled with Fisher’s distinctive visual flair, made him natural for Hammer’s horror movies, of which he directed the large bulk during the late 50’s and 60’s, into the mid-70’s. All in all, Fisher directed 29 films for Hammer, 12 starring Christopher Lee and 13 starring Peter Cushing. Naturally, he is best remembered for his Frankenstein and Dracula films, of which he directed several, Horror of Dracula (1958) and The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) often considered the best, but there are others worthy of mention, like The Mummy (1959), The Hound of Baskervilles (1959), Fisher’s personal favourite, the melancholy The Gorgon, and the Lovecraftian The Devil Rides Out (1968). Outside of his Hammer ouvre, his best known film is perhaps the SF thriller Night of the Big Heat (1967), made for Planet Film.

Fisher directed 12 SF movies: Stolen Face (1952), Four-Sided Triangle (1953), Spaceways (1953), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959), The Earth Dies Screaming (1964), Island of Terror (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Night of the Big Heat (1967), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974).

With his laser focus and piercing blue eyes, Peter Cushing became an almost instant horror icon in 1957. For two decades he became synonymous with Hammer horror, making his own the characters of Victor Frankenstein, Abraham van Helsing and Sherlock Holmes. Cushing, born in 1913, pursued acting at a young age, appearing on stage before making a brief detour to Hollywood 1939-1941. After serving in WWII, he returned to the stage and in the early 50’s became a minor star of British TV, which at the time consisted mostly of teleplays — his performance in the BBC adaptation of 1984 is particularly well remembered. He also has the distinction of being one of the many Dr. Who’s, even if he never played the character in the TV series, but in two rather poorly received movie spinoffs in the mid-60’s. Cushing found a whole new audience in 1977, when he appeared as the ominous Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977). Cushing retired in 1986 and passed away in 1994. He won a best actor BAFTA in 1956, and has been awarded several lifetime awards for his contribution to genre cinema. In 1977 he was nominated for a best supporting actor Saturn Award for Star Wars.

While best known as a horror actor, Peter Cushing appeared in 18 science fiction movies. Cushing’s SF films include: 1984 (1954), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965), Island of Terror (1966), Dalek’s Invasion of Earth 2150 A.D. (1966), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Night of the Big Heat (1967), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), Scream and Scream Again (1970), Horror Express (1972), The Creeping Flesh (1973), Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974), At the Earth’s Core (1976), Star Wars (1977), Shock Waves (1977) and Biggles (1986).

A successful actor in both films and TV, as well as on stage, Francis Matthews first made a name for himself with Hammer, playing the heroic roles in The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966) and Rasputin, the Mad Monk (1966). Shortly after, he voiced the titular character in Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s “Supermarionation” show Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons (1967-1968). After this he went on to play the lead in the crime mystery show Paul Temple (1969-1971). His movie career lasted from 1955 to 2012, and he kept busy, primarily as a guest star in TV shows or in supporting roles in movies, while he also appeared on stage.

Michael Gwynn was a busy character actor whose movie and TV career spanned from 1952 to his death in 1959, only 59 years of age. His best remembered role remains that of Karl, the “monster”, in Hammer’s The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958). He appeared in several Hammer films, including The Camp on Blood Island (1958), Never Take Sweets from a Stranger (1960) and Scars of Dracula (1970). He also had a role in MGM-Britain’s SF/horror movie Village of the Damned (1960). Among his TV work, a standout role was as the false Lord Melbury in the very first episode of Fawlty Towers in 1975.

Eunice Gayson, who began her movie career in 1948, is known for two things: for appearing in the thankless role of wallflower in Hammer’s The Revenge of Frankenstein, and for being the very first Bond girl, and one of the few Bond girls to appear in multiple 007 films. As Sylvia Trench, she is the first girl to be seen with Sean Connery in Dr. No (1962), and is thus officially the first Bond girl. She reprised the role in From Russia With Love (1963). The original idea was that she would become a recurring character, but was dropped from the third film. In the Bond movies, she was dubbed by Nikki van der Zyl — most female actresses were dubbed in the first two films. After her Bond experience, Gayson worked only as a guest star on TV and left the business in 1972.

It was Hammer that made Richard Wordsworth’s film career. Wordsworth had next to no film experience prior to The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), and was contacted by director Val Guest after he had seen him performing with the Royal Shakespeare Company. Guest thought that Wordsworth’s lanky, gaunt look, his deep-set eyes and prominent cheek-bones gave him the perfect look for the astronaut being devoured and transformed from the inside by the alien. Bill Warren in his book Keep Watching the Skies! laments that Wordsworth’s film career never took off the way it might have, but in fact this was a choice made by Wordsworth himself. Wordsworth was offered the role of the Frankenstein creature in The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) but turned it down, because he wasn’t interested in repeating similar roles in other films, and instead opted to focus on his theatre work. Thus, of course, opening the door for Christopher Lee to conquer the world as the titular, and many other, monsters. However, he did play a very different role, as the mischievous patient at the poor hospital in the sequel, The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958(. He also accepted a few roles in other Hammer productions and did quite a lot of TV work. He had one of the lead roles in the sci-fi TV series R3, which ran for one season in 1964, and guested on a couple of other British sci-fis in the eighties. Wordsworth was the great-great-grandchild of celebrated poet William Wordsworth.

Michael Ripper, here playing one of the graverobbers who think they are digging up Dr. Frankenstein, is a Hammer legend. He is usually credited for appearing in 35 Hammer films, but Hammer authority Robin Bailes puts the number at 34, as his scenes were left on the cutting room floor in one film. Known for his often brief but always memorable appearances, often as drunks, barmen/landlords or policemen, Ripper brought colour and personality to even the smallest of roles. He often delivered his performances in an over-the-top, comedic fashion, but proved that he was equally apt at serious, dramatic, even understated portrayals, on the rare occasions he got the opportunity. Ripper excelled in turning run-of-the-mill supporting roles into fleshed-out, intriguing characters, all delivered in his instantly regognisable raspy voice, a result of a thyroid infection and surgery.

Ripper switched between stage work and small roles in film from 1936 to 1952, when the afore-mentioned thyroid infection effectively put an end to his stage career, and he switched to film and TV, which required less volume and projection. He made his Hammer debut in 1948, and appeared in a few roles for the compan before getting cast in the unofficial Quatermass sequel X the Unknown (1956, review), in a small role as a military officer. The same year he appeared in the first feature film adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 (1956, review) He also appeared in the official Quatermass sequel, Quatermass 2 (1957, review), as a barman who eventually is part of the mob that storms the alien base in the English countryside. Ripper only appeared in one of Hammer’s Frankenstein films, The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) – as a drunk – but appeared in several of the studio’s Dracula movies, and in its werewolf and mummy franchises.

And while Ripper is always enjoyable in small bit-parts, the range of his acting talent is on display in his larger supporting roles – most often provided by Hammer – such as the ex-pirate and coffin maker Mipps in Captain Clegg (1962), as the closet-drunk inspector in Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970) and as the villager who loses his family to a vampire in Scars of Dracula (1972). One director who appreciated Ripper’s acting talent was John Gilling, who directed him in three films in 1966 and 1967: The Plague of the Zombies, The Reptile and The Mummy’s Shroud. Gilling gave Ripper substantial dramatic parts in all three films, and they represent some of his best movie work. Particularly memorable are his roles in the latter two. In The Mummy’s Shroud, not a very good film, he plays the downtrodden yes-man to John Phillips’ millionaire hunting Egyptian artefacts, easily the memorable character in the movie. In The Reptile, Gilling actually gave Ripper a heroic co-lead as (again) barman Tom Bailey.

Ripper’s lasting legacy will always be the sheer wealth of characters he did for Hammer, but he did also have a thriving career outside of the studio, often forgotten. He appeared in David Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948), Laurence Olivier’s Richard III (1955), George Schaefer’s TV adaptation of Macbeth (1960) and in the John le Carré spy drama The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965). He had recurring roles in the popular TV shows Jeeves & Wooster, Worzel Gummidge, and not least Quatermass and the Pit, and appeared in guest parts on shows like EastEnders, The Saint and Coronation Street. All in all, Michael Ripper appeared in nearly 250 movies or TV shows, and made his las appearance in 1995. For a much more informed love letter to Ripper, please check out Robin Bailes‘ tribute here.

Playing the other graverobber in The Revenge of Frankenstein is another beloved character actor, although one who made a slightly bigger name of himself, namely Lionel Jeffries. Jeffries, born 1925, began losing his hair while barely into his 20s, a fact which he blamed on the humidity in Burma, where he served in WWII. He trained at RADA, during which he made his first film appearance in 1950, and beside repertory theatre, soon began appearing regularly on the silver screen. Never a leading man as such, Jeffries played smaller and larger supporting roles throughout the 50s in a number of genres, but was particularly in demand for comedic roles. Because of his baldness, he often played characters significantly older than himself.

The 60s was the high point in Jeffries’ career. He played significant and memorable supporting parts and even co-leads in a number of high profile pictures, such as The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1962), The Wrong Arm of the Law (opposite Peter Sellers, 1963), the Miss Marple adaptation Murder Ahoy (1964), The Spy With a Cold Nose (1966), for which he was nominated for a Golden Globe, Camelot, as King Pellinore (1967), and perhaps most notably as Grandpa Potts in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). It was also during the 60s that he parttook in two “adaptations” of classic science fiction novels. He played the co-lead as Prof. Cavor in Nathan Juran’s First Men in the Moon (1964), with animation by Ray Harryhausen, and had a large part in Jules Verne’s Rocket to the Moon aka Those Fantastic Flying Fools (1967), which is not really based on Jules Verne, and is really only science fiction in name. Smaal roles in Hammer’s in The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) were his only other SF outings on the big screen.

In the 70s Jeffries focused on his stage career and appeared only sporadically in movies. He had been avoiding TV work his whole career, as he though the small screen beneath him. However, after reluctantly agreeing to a couple of appearing in a few TV roles in the early 80s, he realised that the production values in TV had caught up with the movie industry, and spent much of the 80s and 90s in television. Jeffries last TV appearance was a guest spot on the Showtime science fiction TV show Lexx in 2001, after which he retired due to his failing health.

Other recognisable faces – if not necessarily names – in The Revenge of Frankenstein are John Welsh, John Stuart, Arnold Diamond and Geoffrey Woodbridge.

Irish actor John Welsh here plays one of the members of the medical board. Character actor Welsh appeared in over 200 films or TV shows, and was a staple on British TV, remembered for recurring roles in shows like The Forsyte Saga (1967), Softly, Softly (1966-1967), The Moonstone (1972) and The Duchess of Duke Street (1976-1977). Science fiction fans might recognise him as the Seer in Krull (1983). Other SF movies were The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) and Konga (1961).

Had The Revenge of Frankenstein been made in the silent era, Scottish star John Stuart would probably had played the lead. Stuart entered movies in the early 20s, and by the end of the silent era, he was one of Britain’s most popular actors, expecially with the ladies. In 1925 he had a co-lead in Alfred Hitchcock’s directorial debut The Pleasure Garden, but it was four films made in 1926-1927 that cemented his fame: the three war movies Mademoiselle from Armentieres (1926), The Flight Commander (1927), and Roses of Picardy (1927), as well as the proto-feminist drama Hindle Wakes (1927), based on Stanley Houghton’s controversial play. All four films were directed by Maurice Elvey. Such was Stuart’s popularity that he was frequently mobbed by female fans, and occasions had to get police escort to premieres and public appearances out of fear of his clothes being ripped to pieces by female fans.

Stuart transitioned successfully to sound (as did, as opposed to popular belief, most silent actors). He appeared in Hitchcock’s mystery comedy Number Seventeen (1932), and played leads or large supporting roles in a number of movies, some smaller and some bigger. For genre fans he might be familiar as one of the leads in G.W. Pabst’s brilliant L’Atlantide (1932), as one of the two soldiers who are lured into the mysterious and ageless queen Antinea in the Sahara desert, who take them as her captive lovers.

In the latter part of the 30s Stuart focused on his stage career, and his marquee value dropped, however, he remained an in-demand actor for film and early TV throughout the 40s. His early television outings are especially interesting for friends of science fiction. In 1948 he appeared as one of the industrialists in a BBC adaptation of Karel Capek’s play R.U.R., only the second movie or TV adaptation of the play (now lost, unfortunately). In the mid-50s he appeared in three SF themed children’s serials, The Lost Planet and Return to the Lost Planet (1954-1955) on TV and Raiders of the River (1956) in cinemas.

While he no longer commanded larger roles in the 50s, Stuart’s high work ethic saw him take on small roles, mostly bit parts, in low-budget films and TV shows. It was also in the early 50s that he began his association with Hammer, which would continue for over a decade. He had small roles in a number of Hammer’s science fiction and horror movies: Four Sided Triangle (1953, review), Quatermass 2 (1956, review), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Blood of the Vampire (1958, review), The Mummy (1959) and Paranoiac (1963). He also appeared in MGM’s Village of the Damned (1960). Otherwise, the 60s and 70s were mostly spent alternating between stage work and TV guest spots. In 1978 he had a tiny role in Superman as one of the Elders. In The Revenge of Frankenstein, Stuart plays a the police inspector who shows up in the end of the movie.

RADA trained Arnold Diamond had a successful stage career, but was mostly seen in bit parts on screen and guest spots on TV between 1947 and 1992. He shows up, for example in blink-and-you’ll-miss-him roles in The Italian Job (1969) and Fiddler on the Roof (1971). He is perhaps best known for playing Col. Latignant, one of the few recurring roles besides that of Roger Moore’s in the TV show The Saint (1963-1966). Most of his science fiction credits are from the small screen. He appeared in the groundbreaking TV show The Quatermass Experiment (1953, review) as well as the famed BBC live broadcast of George Orwell’s 1984, starring Peter Cushing (1954). On film he appeared in The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), as a member of the medical board, The Hands of Orlac (1960), Masters of Venus (1962), as the Venusian Imos and The Vulture (1966) as a doctor.

George Woodbridge was another prolific bit-part and character actor, active on the screen between 1940 and 1974, best known for his many appearances in Hammer horror movies. He was also a staple in comedy films. According to Wikipedia, “Woodbridge’s ruddy-cheeked complexion and West Country accent meant he often played publicans, policemen or yokels”. In the Hammer universe, he is perhaps best remembered for playing the landlord in Dracula (1958) and Dracula: Prince of Darkness. In The Revenge of Frankenstein he has a pivotal role as the janitor who smashes the newly operated Michael Gwynn over the head with a chair, damaging his still healing brain. Woodbridge’s only other SF credit on the big screen is Doomwatch.

Charles Lloyd Pack played Dr. Seward in Dracula (1958) and also turned up in Quatermass 2 (1956) and The Man Who Could Cheat Death (1959), as well as in a number of Hammer horrors.

One of these days I’m going to do a dive into the careers of key Hammer personnel like Jimmy Sangster, Tony Hinds, Jack Asher and Phil Leakey, but the cast list here is already a mile long, so it’s probably best to save that for another time.

Janne Wass

The Revenge of Frankenstein. 1958, UK. Directed by Terence Fisher. Written by Jimmy Sangster, Hurford James, George Baxt. Starring: Peter Cushing, Michael Gwynn, Francis Matthews, Richard Wordsworth, Eunice Gayson, Oscar Quitak, John Welsh, Lionel Jeffries, Michael Ripper, Charles Lloyd Pack, John Stuart, Arnold Diamond, Marjorie Gresley, Anna Walmsley, George Woodbridge. Music: Leonard Salzedo. Cinematography: Jack Asher. Editing: Alfred Cox. Production design: Bernard Robinson. Makeup: Philip Leakey. Sound recordist: Jock May. Wardrobe: Rosemary Burrows. Produced by Anthony Hinds for Hammer Films.

Leave a comment