The Tokyo police are flabbergasted when gangsters start melting. Ishiro Honda mixes the police procedural with gooey body horror in this 1958 cult classic. Fun effects and good atmosphere counteract a plodding and confusing script. 6/10

The H-Man. 1958, Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Takeshi Kimura, Hideo Unagami. Starring: Yumi Shirakawa, Kenji Sahara, Akihiko Hirata. Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka. IMDb: 6.1/10. Letterboxd: 3.0/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

On a rainy night in downtown Tokyo, a gangster named Misaki (Hisaya Ito) disappears in the middle of a drug heist, leaving behind him all his clothes and belongings, as well as the drugs. Police inspector Tominaga (Akihiko Hirata) and his colleagues are baffled, and latch onto Misaki’s girlfriend, nightclub singer Chikako Arai (Yumi Shirakawa). However, Arai knows nothing about anything, and the flatfoots are stumped, despite shaking up half of Tokyo’s underworld in order to get answers. Nobody takes note of the young Dr. Marada (Kenji Sahara), who says that he might actually have the answer: Misaki has been dissolved by a living, radioactive blob.

So begins Toho’s 1958 movie The H-Man or, 美女と液体人間, pronounced Beji to ekitai ningen, which translates as “Beauty and the liquid man”. Behind the film stands the two giants of Toho’s science fiction franchise, director Ishiro Honda and special effects designer Eiji Tsuburaya, responsible for bringing to the world Gojira (1954, review). The H-Man was the first in Toho’s early cycle of “Transforming Human” or mutant trilogy, also including The Secret of the Telegian (1960) and The Human Vapor (1960).

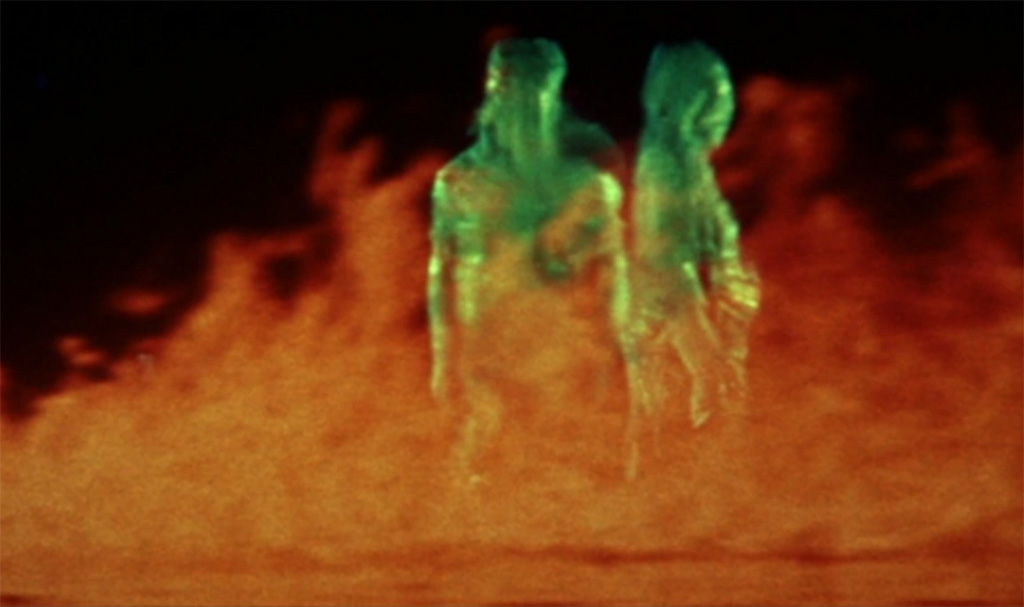

The plot is somewhat convoluted, but I’ll try to make sense out of it. It all begins with a ghost ship drifting outside the coast of Japan. The ship had passed through a H-bomb test, which dissolved its crew, turning them into conscious, living puddles of goo, sometimes manifesting as green, humanoid gas beings. These blobs are first witnessed by a crew of fishermen (including legendary suit actor Haruo Nakajima, in a rare non-suit role) inspecting the seemingly abandoned ship, only to have half of their team devoured by the blobs.

Despite gangsters disappearing left and right, leaving guns and clothes behind them, inspector Tominaga is not swayed by ghost stories by simple sailors, nor the science fiction babble from Dr. Marada and his colleagues, despite the fact that Marada shows him his experiment where he turns a toad into jelly by way of radiation. Tominaga and his many colleagues believe that we are dealing with a simple case of gangster rivalry, and is convinced that Ms. Arai knows more than she is letting on. Somehow the footprints seem to lead to mob boss Uchida (Makata Sato) — or at least after Tominaga has gone through all the other Tokyo mobsters anc come up empty-handed.

Meanwhile, Ms. Arai is more popular than ever. Not only is the police interested in her, but she is also paid a visit by am Uchida henchman, who gets gobbled by a blob beneath her window. Furthermore, Dr. Masada also takes a more than professional interest in her. While the police chase their tails and the research team hesitates to go public with their findings, the blobs attack the nightclub where Arai sings and Uchida hangs out. After devouring a number of gangsters, police officers and a bikini-clad dancer, one of the blobs attack Arai, who is saved by the police who pepper the blob with lead, and force it to retreat. Having wintessed the blobs with his own eyes, Tominaga is now ready to become a believer.

As in most Toho SF movies, we now get a scene of dozens of people whom we hardly know gathering around a large table with a map, laying out plans to defeat the blobs. Dr. Masada’s boss, Dr. Maki (Koreya Senda), lays out the explanation: the sailors on board the ill-fated ship have all been turned into living slime (who sometimes manifest as a green vapour in humanoid form), who devour living people. The remnants of their human consciousnesses have brought them to Tokyo, where they are all now residing in the sewers of a couple of downtown blocks. Dr. Maki explains that the only way to kill them is to burn them. Said and done: Tominaga calls in all available forces to pour gasoline into the sewers and set them ablaze. However, after a car chase, gangster Uchida kidnaps Ms. Arai, because apparently he also thinks she is hot, and drags her down into the sewers, where he gives her an ultimatum: marry him of become blob food. He has her strip her clothes (fortunately whe wears well-covering underwear) in order for the authorities to think she has been liquefied. But Dr. Masada sees her blouse floating out of the sewers, and just minutes before the place is about to be set on fire, he ventures into the depths in order to find and rescue her ….

Background & Analysis

In the mid-50s, director Ishiro Honda led Toho’s charge that would turn the studio into one of the world’s leading producers of science fiction movies (even though only a handful of the 26(!) films he directed between 1954 and 1960 were SF). After Gojira (1954), he turned his eyes to the short-lived yeti craze with Ju jin yuki otoko (1955, review), returned to kaiju fare with Rodan (1956, review), and took on the alien invasion with The Mysterians (1957, review). And in 1958, he returned back to where it all began, with the US nuclear tests outside Japan and the tragic fate of the crew of the fishing boat “Daigo Fukuryu maru” (“Lucky Dragon 5”), who came down with radiation poisoning after the Americans blew off a much bugger H-bomb than anticipated off the Bikini atoll. The incident prompted Honda to make Gojira, and was mirrored in the film’s opening scene in which Godzilla attacks a fishing boat. The H-Man opens with a scene of the irradiated, now seemingly deserted vessel “Daini Ryujin Maru” (“Dragon God 2”), whose crew are also the victims of radioactive fallout. The film also ends on an ominous voice-over informing us that if the world was covered in nuclear fallout, then the H-men would become the new dominant species on Earth.

The original story for The H-Man was penned by Hideo Unagami, a theatre actor working for Toho’s theatre department, who also wrote story treatments for their film studio (none of which were ever used), and appeared in minor roles in a handful of films. It was during the filming of The Mysterians, in which he had a small role, that he penned the story for The H-Man. Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka of Gojira fame liked the story, and decided to make a film out of it. Unfortunately, Unagami passed away shortly after The Mysterians had premiered. The story was adapted into a screenplay by Takeshi Kimura, who had previously written both Rodan and The Mysterians. Having a good working relationship with Kimura, one can assume that Honda had lots of input into the screenplay as well, seeing as it bears several of his trademarks.

However, more than Toho’s previous SF output, The H-Man resembles the “invisible man” films by rivalling studio Daiei, in particular The Invisible Avenger (1954, review) and The Invisible Man vs. the Human Fly (1957, review), in that it merges the SF genre with the popular gangster noir genre. These crossover films heavily rely on the popular Japanese noir tropes, inspired by American 40s noir, switching between hard-boiled cops interrogating gangsters and mob molls in claustrophobic police headquarters, and seedy dealings in smoky nightclubs, almost inevitably with a couple of jazz numbers sung by one of the female co-leads, and risque dance numbers by girls in glittery bikinis.

The SF element of the film is quite straightforward, if somewhat illogical. Fishermen get irradiated and turn into blobs that devour people for sustenance, make their way to Tokyo and start wreaking havoc. Scientists and police identify and track down the menace, leading to an urban showdown in the sewers. The SF element really combines two tropes. One is taken from Daiei’s invisible man films, in which people who have in some way or the others been left scarred from war experiences turn invisible and start exacting revenge on society. The other trope is taken from US monster movies, in which giant bugs were often cornered in some major city, where the military and scientists take them out with some ingenious tactic. In this case, the ending particularly resembles that of Them! (1954, review), in which the giant ants are incinerated in the Los Angeles storm drains. In the past, The H-Man was often considered a ripoff of The Blob (1958, review), as it was released in the US in 1959. Today, it seems common knowledge that the two films were in production simultaneously, and The H-Man actually premiered several months before The Blob in Japan.

The film triumphs in Eiji Tsuburaya’s ingenious special effects – while crude today, they reportedly scared the heebie-jeebiees out of kids in the 50s – and in Ishiro Honda’s dark, rain drenched, atmosphere. The monster of this film was a fairly novel concoction, although one can draw comparisons to BBC’s and Hammer’s Quatermass franchises, in particular to Hammer’s unofficial sequel X the Unknown (1956, review), in which a radioactive blob melts its victims. The H-Man also manages to build up a good deal of mystery built up around the menace. While the audience is made privy to the basic idea of what the killer blobs are, their motives and nature remain elusive until the very end …

… unfortunately until the very, very end, as we know little more about them after the finishing voice-over than we did a third into the movie. Obvious questions remain, such as why the blobs choose to invade the seedier parts of Tokyo, and why they seem to have a fixation on gangsters, Ms. Arai and the nightclub in which she performs. Dr. Maki at one point states that it was the surviving consciousness of the sailors that drew them to Tokyo, but this only opens up new questions. Why did they feel drawn to Tokyo and start to target gangsters and nightclub performers? During the entire film, we wait for an answer as to why Ms. Arai is at the centre of all the gooey proceedings, but alas, the film offers no answer.

Likewise hanging in the air at the end of the movie is the gangster plot, which takes up two thirds of the film. Most of the picture follows inspector Tominaga shaking down the mobster world of Tokyo, trying to find out who killed Misaki, or whose drugs Misaki stole, etc, while we the viewers are aware that Misaki was killed by a radioactive blob. At some point we start suspecting that Misaki is in fact the blob, but the movie never confirms this either. It seems to say that the blobs are the sailors, but it never rules out that the people devoured by the blobs might become blobs themselves. In the end, the gangster plot really has nothing at all to do with with the SF plot. In a desperate attempt to at least superficially tie the two story strands together, screenwriter Kimura has to come up with the contrived plot twist at the ending that sees Uchida kidnap Ms. Arai out of a sudden infatuation with her. This infatuation has never even been alluded to during the rest of the film, and has no bearing on either of the two plot strands. The original script had Dr. Masada volunteering to turn himself into an H-man in order to find out where the other H-men hung out – only to be beaten to the act by Ms. Arai. It is possible that this idea was scrapped because it was a direct ripoff of the ending of The Invisible Man vs the Human Fly (come to think of it, there’s quite a lot in The H-Man that resemble’s Daiei’s film). But this would at least have made for a more interesting take on the H-man theme, and brought a stronger character drama to the movie. It also explains the contrived ending that we got – clearly Kimura and Honda struggled with what to do with the climax.

The weaknesses of The H-Man’s script are familiar from both Rodan and The Mysterians, both of which Takeshi Kimura also scripted. In both movies, Kimura struggled to fill out the plot between start and finish. Once the premise is presented, he flounders to get to the resolution and tends to fill out the films with padding, punctuated by a few great, climactic scenes here and there. It is as if Kimura has a bullet point of scenes which make out the highlights of the movie, but never a clear dramatic arc defining how to get from one highlight to the next. He clearly struggles to write characters. All three Kimura films I have reviewed thus far have incredibly weak characterisations and an almost complete lack of any engaging character drama. I have previously mentioned the fact that his films often seem to lack strong central characters, and it is as if all action is performed by committee. This is partly explained by Japanese culture, which downplays the individual and emphasises the collective. But that didn’t stop Takeo Murata from writing a gripping character drama between the three central characters in Gojira, for example – a drama that was at the heart of the story, crucially.

In The H-Man, Ms. Arai seems to be the central character, but she has no personal stake in the plot, no motivation, and thus remains a bystander, despite everything seemingly revolving around her – a fact that ultimately seems to be pure coincidence. At some point it seems that it is inspector Tominaga that is going to be the driving character, and Akihiko Hirata plays him well, but he lacks a character arc and ultimately has no real personality or motivation. He is made slightly more interesting by being a bit of a dick, but that mostly feels like a plot contrivance – he needs to disbelief in order for the film to reach its allotted running time. Dr. Masada is ultimately the hero that saves the day, but he is such a bland goodie-two-shoes character that there’s nothing for an audience to get interested in.

All this is not enough to sink the film, but it does make it a bit of a slog. As do the over-long musical and dance interludes that seem to have been ubiquitous to Japanese gangster movies, and thus also to the crossover films. Here Chikako Arai performs two mellow, smoky jazz numbers in a deep husky voice that differs significantly from actress Yumi Shirakawa’s speaking voice. Shirakawa mouths the songs skilfully, but the voice is that of jazz star Martha Miyake. Likewise, the film offers up two fairly lengthy exotic dance numbers, with actress Ayumi Sonoda in the spotlight. I can understand that these numbers were expected by the audiences of the popular noir genre in Japan, and they are all quite well executed, but they have no dramatic value and only serve to grind to story to a halt. However, the jazz band is KILLING IT! It’s worth noting that the jazz songs were written by the film’s composer Masaru Sato.

Fortunately, if the film’s script and characters are on the weak side, The H-Man has lots of other things to offer. Honda’s direction is fairly brisk, and he excels in showcasing the seedy side of Tokyo by Hajime Koiziumi’s atmospheric colour photography and Takeo Kita’s production design. Unlike the ponderous Rodan and The Mysterians, The H-Man is made with a sly wink at the audience and refrains from taking itself too seriously, and the dips in energy caused by the prolonged police procedural plot are counteracted by a number of fun, colourful side characters.

The stars of the movie, however, are Eiji Tsuburaya’s exquisite miniature shots and special effects. As stated, the effects might seem crude by today’s, and even yesterday’s, standards, but considering the era in which they were made, they are quite effective. We get numerous shots of people melting out of their clothes, slowly crumpling over themselves while goo seeps out of their shirts and pants. Film historian Bill Warren testifies that his cousin “was frightened nearly into catatonia” by the effects when he saw the movie upon its US release, and for years thought of the film as “the scariest thing he ever saw”. According to the author of Apocalypse Then: American and Japanese Atomic Cinema, 1951-1967, Mike Bogue, the effect was created through the “simple but ingenious method” of creating life-size inflatable models of the actors and then slowly deflating them while over-cranking the camera – all while pumping goo out through their clothes.

According to Tsuburaya, the goo was made using “a special chemical compound”. In reality, it was a slime made from finely chopped kelp that had been dissolved in water. In some scenes, they would use pressure to pump it through windows and doors. In other scenes they would create the illusion of the slime slithering upwards or sideways on ceilings by simply building a model on its side or upside down, and tilt the camera, and then just let gravity do its work. While the technique is obvious to an adult viewer, the effect is still highly effective. In some scenes, the goo seems to have been filmed against a black backrop and superimposed on the main footage, and these scenes work almost seamlessly. The effects are least effective when Tsuburaya needs to resort to cel animation, making the whole thing look cartoonish. One shot in particular is very bad, namely one in which the bikini-clad Ayumi Sonoda is devoured by the goo. In order to make the shot work, Tsuburaya freeze-frames Sonoda and adds a poorly executed animation on top of her. This scene was cut from the US version when Columbia released it in 1959. Film buffs who were not able to see the Japanese version for a long time assumed that the scene was cut because of its gruesomeness, but in all probability Columbia left it on the cutting room floor because of its shoddiness.

Especially well executed are the final scenes in Tokyo sewers. The live-action scenes were partly filmed inside the real sewers of Tokyo (Kenji Sahara later recalled the terrible smell on location), and for effect shots Eiju Tsuburaya built highly realistic miniatures. These two are seamlessly integrated and very eerily and atmospherically shot by both Honda and Tsuburaya. In the end, Tsuburaya sets the entire miniature set ablaze. The shots of the burning gasoline slowly spreading across the water surface are a sight to behold, and in the climax the flames travel out across a carefully executed miniature model of the Tokyo seafront, setting the night sky ablaze. This must be one of the most breathtaking finales of any science fiction film of the 50s.

The music of the film is a somewhat mixed and eclectic bag. Masaru Sato happily combines styles that clash jarringly with each other. The most egregious theme is an upbeat and way too imposing military march which is first heard in the beginning of the movie, and which makes a couple of returns in scenes where we are gearing up for a dramatic climax. This theme seems completely out of sync with the movie’s dark, noirish style. Then there’s the jazz parts, which are good on their own and certainly sets the mood for the club scenes, but that take up way too much space in the film. Most of the soundtrack has a lot more subdued, sometimes almost electronic sounding music, using instruments like a saw and a glass harp to create otherworldly sounds, fitting both the SF horror atmosphere and the noir style.

The H-Man continues Japanese cinema’s long and arduous process of coming to terms with WWII, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the crippling blow to the nation’s pride that was the US occupation. Few films have surpassed Gojira in the masterful way the movie was able to comment – surprisingly thoughtfully – on all of these issues, through the unlikely vehicle of a giant radioactive dinosaur. The devastation of the nuclear bomb was seared into the consciousness of Ishiro Honda, and he returned to the theme again and again, despite sometimes lamenting the movie business being stuck in cold war topics. What symbolism we are ultimately to read into the H-men of Honda’s film is really up for grabs, as the living blobs don’t seem to have any real agency in the movie. Perhaps Honda wasn’t really sure himself. The final monologue brings up the fear of the entire human race being reduced to H-men by a nuclear war. This seems a dire warning of, basically, mankind wiping itself off the map. Mike Bogue, on the other hand, makes the argument that the H-men are to be taken as symbols for all those affcted by the nuclear fallout from the American bombings – that radiation dehumanizes you, changes you past the point of no return. He suggests that this could be a conscious or unconscious reference to the “hibakusha”, the survivors of the A-bombings: “Certainly, these unfortunates felt a sense of contamination, of otherness”.

As an anti-nuclear film, The H-Man would have made its point even without the tacked-on voice-over at the end – as if Honda was unsure of the audience would understand the message. If there is any other message or symbolism in the film than a general warning against nuclear weapons, it remains foggy. The plot itself seems to contain little thematic content: as far as the plot goes, it makes no difference whether the murderous blobs had arrived from outer space or been created by an H-bomb. At heart, the movie is an entertainment product, and when analysing it one should remain aware of Maslow’s hammer: for someone writing a book on Atomic cinema, everything may easily look like nuclear symbolism.

The H-Man handily overcomes its scripting and plotting problems through the entertaining individual scenes, the overall atmosphere, the great production design, Honda’s capable direction and Tsuburaya’s inventive special effects – always a joy to watch, regardless of the the quality of the rest of the movie. One does wish that screenwriter Kimura would have done a better job at connecting the gangster and the science fiction plot – or discarded one for the other in order to make more space for character drama.

Release & Legacy

Bijo to ekitai ningen premiered in late June in Japan, and must have done faily good business, as Toho returned to the Transforming Human subgenre several times. It took almost a year to get the the US, where its novelty was somewhat dampened by the release of The Blob the year before.

The US dub, according to those who have seen it, stuck closely to the original, albeit with a few of the actors adding some stereotypical Japanese accents. Columbia cut nine minutes from the Japanese version. Since the Japanese version was long hard to come by outside Japan, many non-Japanese SF aficionados have speculated in what was cut. Some have guessed that the US censors removed special effects that were deemed to gory, but in fact the only effect that was cut was the scene of the dancer getting liquefied. Otherwise, Columbia mainly removed gangster plot elements. I am told these cuts do create some confusion regarding the plot, but also that it makes the pace snappier than in the original film.

Finding historical reviews for old movies in a language written in an alphabet you can’t read is nigh impossible, and none of the sources I have scoured have any mention of how The H-Man was received in Japan upon its release. However, the reception by the Hollywood trade press upon the film’s release in the US was fair to positive. The Motion Picture Daily wrote: “The H-Man moves moderately well, so that most horror fans will not notice that it often gets bogged down in irrelevancies”. Harrison’s Reports noted that the “mixture of science fiction and crime melodrama makes for a fast-moving program exploitation picture”. The magazine also said that the special effects were “well done and sometimes even frightening”. Variety was also positive. British Monthly Film Bulletin was divided: “The H-Man has all the usual faults and virtues of Japanese SF-cum-horror fiction. The story is imitative and undisciplined, spending far too much time on an erratic police v. racketeers subplot, which is vague and gets nowhere; characterisation is virtually non-existent […] But for special effects, trick photography and spectacular staging, the Japanese again beat their Hollywood counterparts at their own game”.

As of writing, The H-Man has a decent 6.0/10 rating on IMDb, based on around 1700 votes, and 3.0/5 rating on Letterboxd. based on 1900 votes. Critic aggregate Rotten Tomatoes does not have enough reviews for a consensus.

Modern critics are divided on the film’s merits. One of the few Japanese reviews I have found comed from user Yoshirin at Ameba, who, like some of the critics of old, laments the movie’s confusing plot: “The climax in the middle, the scene where the cabaret is being cleaned up [by the police], is not explained very well, so it is hard to understand what is going on, and the Liquid Man bursts in and leaves that part unclear”. Yoshirin concludes: “compared to the later [films in Toho’s “Transforming Human” series], it is lacking. The underworld parts featuring Sato Masaru and Nakamura Tetsu seem tacked on and are not intertwined with the main story, giving the impression of being out of place.”

Both Richard Schieb at Moria and Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum give The H-Man 2/5 stars. Lovell says: “You can see where all of this may have been fun but The H-Man doesn’t have quite what it takes to be completely successful. The big problem is that director Inoshiro Honda’s pacing is so damn constipated.” While Scheib opines that the crime drama “is not particularly well written – it is exceedingly difficult to follow some of the logic that the police investigation follows – you are not even sure why they are investigating the nightclub and how this ties to the ghost ship at sea and the H-Man causing the disappearance of people.” He continues: “the routine crime drama policier dominates the show and the appearances of the H-Man are infrequent – such that we are constantly sitting waiting through the dull drama for the effects sequences to come and perk the show up”.

However, there’s also opinions to the contrary. Don Anelli at Asian Movie Pulse thinks that “one of the best aspects [of the film] is the rather ingenious manner Takeshi Kimura’s screenplay weaves together several seemingly random plot points into a cohesive setup”. He concludes: “With plenty of highly enjoyable elements scattered throughout the film, it has enough going for it that [its] minor issues aren’t even worthwhile enough to hold it back”. Nicholas Driscoll at Toho Kingdom notes the film’s flaws, but is forgiving in his 3.5/5 star review: “There are problems to H-Man—uninteresting characters, a dull and confusing car chase, and a slightly bumpy climax mark down what is otherwise a remarkably good Toho thriller.”

Although The H-Man is a standalone film, it has been retroactively lumped together with two other Toho movies made in 1960, The Human Vapor and The Secret of the Telegian, into what is sometimes called the Transforming Human trilogy. Although slightly different, Matango (1964), released in the US as Attack of the Mushroom People, is also sometimes added to this group. David Milner at The History Vortex further adds Latitude Zero (1969) and ESPY (1975) to the list, but it’s questionable whether these qualify. Although some American films have been made that are clearly inspired by the Transforming Human series, no remakes or reboots of these movies have produced. However, now this seems to change: in August, 2024, Toho and Netflix announced they plan to turn The Human Vapor into a streaming series.

Cast & Crew

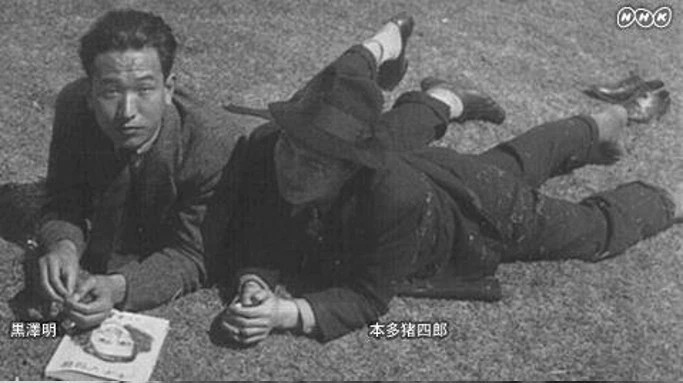

After graduating from film school in 1933, at the age of 22, Ishiro Honda immediately started working as ”assistant assistant director” for a number of directors, and in 1935 he enrolled in the army. During this time, he worked on a number of pictures together with a young Akira Kurowawa, up until WWII. For Honda, the next decade would be spent alternating between the trenches of war and the movie sets. In 1945, on campaign in China, Honda was captured as a prisoner of war, and got left behind as the war ended. He was released in March of 1946 after six months in a Chinese prison camp, and then decided to dedicade his life full-time to the movies. In 1949 Honda worked as first assistant director on rising star Akira Kurosawa’s Stray Dogs, which opened new doors for him, and in 1951 he finally got to make his directorial debut with Aoi shinju (The Blue Pearl). Another important film was his 1952 movie The Man Who Came to Port, not so much for the movie itself, but because it was here he met Tomoyuki Tanaka and Eiji Tsuburaya. The first ended up producing Gojira and the latter created the memorable special effects.

Gojira a smash hit in Japan, and its fame also slowly grew internationally, making kaiju movies the cash cow of Toho Studios. Honda became Toho’s most prized science fiction and kaiju director, and continued directing these films during the entire Showa era (1954-1975), after which little remained in the franchise that was recogniseable from the original movie. After this, Honda went into retirement.

During his career, Honda directed a whopping 31 science fiction movies, finishing off with a handful of TV shows. Despite his vow to never do another Godzilla film after the first one, he eventually returned to his most famous creation with King Kong vs. Godzilla in 1962. He is naturally best known for his kaiju movies, of which he directed over 20, including Gojira (1954), Rodan (1957), Mothra (1961), King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), Destroy All Monsters (1964) and Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975). But he also took on other SF tropes, such as mutants in The H-Man (1958), The Human Vapour (1960) and Matango (1964), submarine shenanigans in Atragon (1963) and Latitude Zero (1969), alien invasion in The Mysterians (1958) and Battle in Outer Space (1959), as well as colliding planets in Gorath (1962).

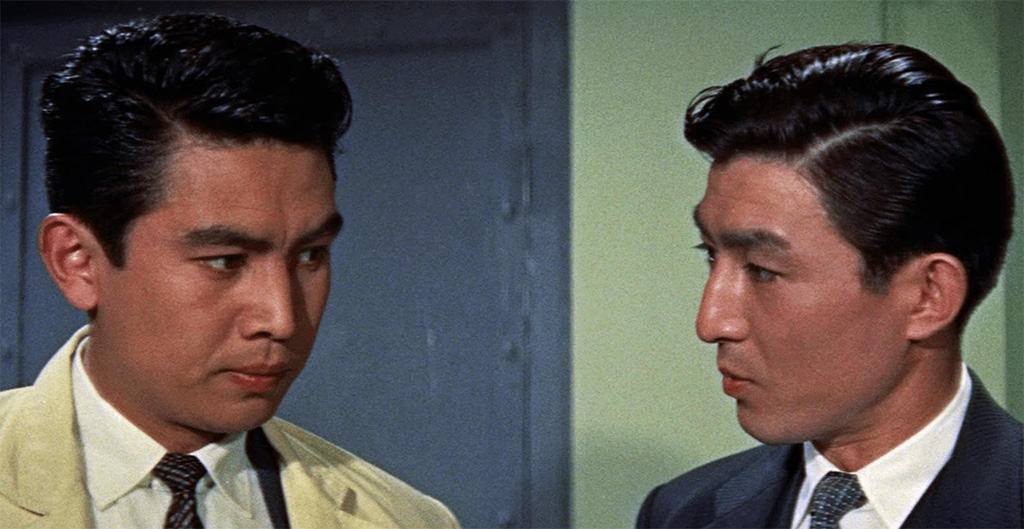

The lead trio are well know to fans of kaiju and tokusatsu films. Yumi Shirakawa, Kenji Sahara and Akihiko Hirata were all favourites of Honda’s, and both Sahara and Hirata had been along for the ride since Gojira (1954). All three played leads or co-leads in both Rodan (1957) and The Mysterians (1957). Shirakawa, billed “the Japanese Grace Kelly” also played the lead in The Secret of the Telegian (1960) and Gorath (1962), but then left the tokusatsu genre behind her, even if she remained a favourite of Honda’s.

Kenji Sahara rose to fame as the soft-cheeked romantic hero in Rodan, and became one of the most recognisable faces in Toho’s science fiction films in the decades to come, playing both heroes and villains. His final Godzilla appearance came in 2004, in Godzilla: Final Wars. In 1966 Sahara played the lead in the first Ultraman series, Ultra Q, and appeared in numerous subsequent Ultraman series. Another actor who became closely associated with Godzilla and the Toho tokusatsu eiga was Akihiko Hirata. With his thin face and cool visage, Hirata became a respected character actor, often playing sinister military types, but also a cult actor withing the tokusatsu genre. He appeared in 20 of Toho’s special effects films.

Yoshio Tsuchiya doesn’t have large role in The H-Man, but was one of Toho’s most prized actors. Originally slated for a career on stage, he was lured into film acting by Akira Kurisa for Seven Samurai (1954). Tsuchiya went on to appear in nearly every Kurosawa film from 1954 onward. At Toho, he immediately became thrilled with the special effects works led by Tsuburaya, and he and Honda soon became great friends. Although fiercly protective of his actor, Kurosawa let Tsuchiya appear in all the sci-fi films he wanted to be in, as long as they could be worked around his own movie shoots. Consequently, he appeared in over a dozen SF movies for the studio. Tsuchiya was fluent in both English and French, rode motocross and played flamenco guitar. That is, besides being a medical doctor and one of Japan’s biggest movie stars.

The singer who dubs Yumi Shirakawa in the nightclub scenes was Martha Miyake, one of Japan’s most popular jazz singers. Like many other jazz artists of the time, Miyake made her bones by singing at US military bases in the 50s, before hooking up with the popular Filipino bandleader Raymond Condé. She received numerous awards during her long career, and both her daughters also became singers. However, The H-Man was her only involvement in the movie business.

The rest of the cast is made up of Toho stock actors, all of whom are recogniseable from a multitude of monster movies. One of these days I’ll get around to writing a bio on Eiji Tsuburaya, but suffice to say that none of Toho’s kaiju movies would have seen the light of day in the form we know then today without Tsuburaya’s ingeneous effects, and in particular his model work.

EDIT 13.09.2024: Corrected the title of the series from Ultraman Q to Ultra Q.

Janne Wass

The H-Man. 1958, Japan. Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Takeshi Kimura, Hideo Unagami. Starring: Yumi Shirakawa, Kenji Sahara, Akihiko Hirata, Eitaro Ozawa, Koreya Senda, Makoto Sato, Ayumi Sonoda, Yoshifumi Tachida, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Hisaya Ito, Haruo Nakajima. Music: Masaru Sato. Cinematography: Hajime Koizumi. Editing: Kazuji Taira. Production design: Takeo Kita. Special effects: Eiji Tsuburaya. Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka for Toho.

Leave a reply to David Hirsch Cancel reply