Robert Vaughn stars in Roger Corman’s 1958 post-apocalyptic caveman film as the rebel who dares to find out what lies beyond the boundaries of his tribe. The idea is neat, even novel, but the script treads water and is beyond silly, and production values nonexistent. 3/10

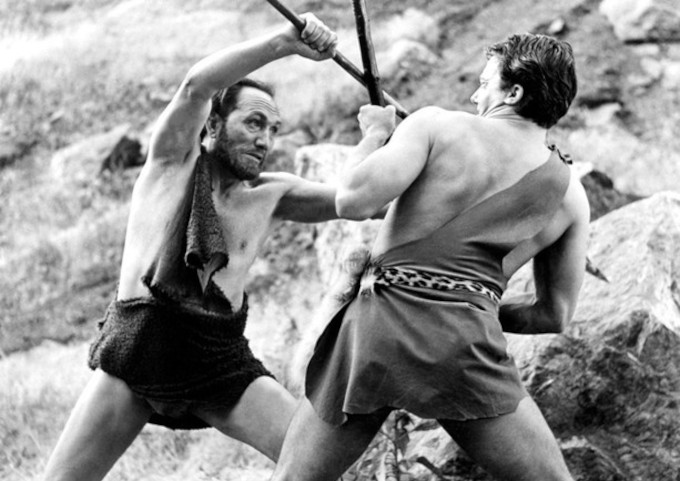

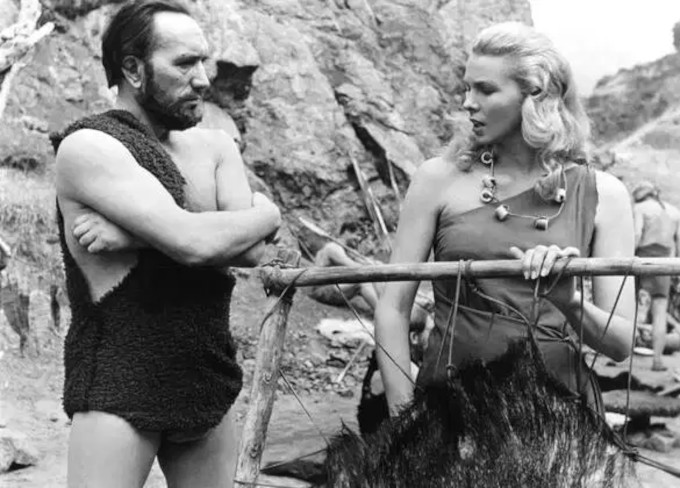

Teenage Caveman. 1958, USA. Produced & directed by Roger Corman. Written by R. Wright Campbell. Based on short story by Stephen Vincent Benét. Starring: Robert Vaughn, Leslie Bradley, Frank DeKova, Darah Marshall. IMDb: 3.5/10. Letterboxd: 2.5/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Robert Vaughn is the son of the Symbol Maker (Leslie Bradley). An inquisitive and rebellious you man, he wants to cross the river to the other side of the valley, where dinosaurs and other creatures roam, and the nature is lush and plentiful. However, it is forbidden by the Law of the Gods. The Gods have decreed that Men must live in the barren part of the land, lest they be punished by death. Of course, this won’t stop a you rebel like Vaughn.

Teenage Caveman (1958) was Roger Corman’s second attempt at a historical “epic”, severely hampered by American International Pictures’ tight budget. Primarily filmed in Bronson Canyon and the woods outside Arcadia, California, the movie had no connection to AIP’s previous hit films I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1958, review) or I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1958, review), but studio executive Sam Arkoff wanted to release it as a double bill with these films’ sequel, How to Make a Monster (1958, review), and changed the title to Teenage Caveman without the consent or knowledge of Corman.

Vaughn is spurred on by a gruff and devious-looking member of the tribe, (staple heavy Frank DeKova), who stokes his fire of finding out what lies beyond. But he is warned about the God that kills with its touch, a strange-looking creature with the face of a bird or rodent but the gait of a man. Vaughn takes a group of young men to the other side of the river, where they find dinosaurs, giant lizards, wild dogs, plenty of food and a bear (Beach Dickerson), which kills one of the men. On his trip, he also invents the bow and arrow. Upon his return, Vaughn is punished with the silent treatment (to be as if dead to the clan), until he has passed the rites of manhood. This doesn’t stop him from chatting up his girlfriend (Darah Marshall) or having long conversations with his dad and DeKova. Neither does he shut up when a strange man (Beach Dickerson, again) comes to the village, riding a horse. DeKova immediately spurs the clan to kill the stranger, because it must be a demon (because there is no such thing as a man on top of an animal). Despite the pleas of Vaughn, DeKova kills him. With his dying breath, the man utters one word: “Peace”. Meanwhile, Vaughn goes over the river again, and this time his dad goes after him. Because of breaking the law, dad is dethroned as Symbol Maker, which seems to have been DeKova’s plan all along, as he now sets himself up as the new Symbol Maker and the de facto leader of the clan.

Vaughn will not stand this hypocrisy, and decides to once and for all face and kill the God that kills with its touch, so that his clan can move to the new, fertile areas. But when he meets it, it turns out to be weak and old, and he notes “this is no evil thing”. Dad decides to go after his son, and when the clan notices they are both gone, DeKova decides that they will also go and hunt for them (because apparently it is OK to pass the river if one does it for the right reasons).

I do not like to spoil twist endings, but it is impossible to discuss this film without spoiling it. If you don’t want it spoiled, then go and watch it on Youtube, its is an hour long.

Dad catches up with Vaughn and DeKova catches up with them. Vaughn puts down his bow and arrow and tries to communicate with the Thing, but DeKova kills it with a rock. Vaughn shoots DeKova and demasks the Thing, which turns out to be an old, withered man. In his suit they find a book, which they cannot read, but from which the audience can get glimpses of the 50s, and the nuclear arms race. A voice-over ends the movie, explaining that nuclear war devastated the Earth, and some people got irradiated and dressed radiation suits like the ones that the Thing is wearing, and were gifted with unnaturally long life. Wildlife was also affected by the radiation, and grew enormous like the dinosaurs of old, or took on monstrous forms (like that of the She-Creature). The “monitors” watched over the rest of humanity, who devolved into cavemen, and put in place the Laws, to protect them from the monsters and to guide them in the future. However, says the narrator, all we have seen in the film happened long ago, and will keep on happening in the cycle of history.

Background & Analysis

One can be forgiven for thinking that Teenage Caveman was filmed as an addition to American International Pictures’ trilogy of teenage monster movies; I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957, review), I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957, review) and How to Make a Monster (1958, review). However, it was nothing of the sort. These three films were all dreamed up, produced and co-written by Herman Cohen, whereas Teenage Caveman was a wholly unconnected Roger Corman product.

This was during a period of Corman’s career when he was starting to mature as a producer (an odd thing to write about someone who had 20-something feature productions behind him), and started taking on more ambitious projects than the small, self-contained monster movies, crime dramas and westerns that littered his résumé. By 1957, he became confident enough to take on historical epics, producing both The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent (1957) and Teenage Caveman (filmed as “Prehistoric World”). However, although Corman’s ambition grew, his budgets didn’t. Both films were made for AIP for the usual budget of around $100,000. In latter interviews, Corman has expressed regret that that the productions didn’t get larger budgets, bemoaning the fact that the lack of time and money showed in the end results. Both productions were fraught with mishaps and potentially life-threatening situations for the actors. In the first film, the Viking ship drifted off into the ocean with the actors aboard, and in Teenage Caveman a bunch of poorly trained dogs were set on one of the actors, who had no padding or protection (luckily it turned out the dogs were even more afraid of him than he of them).

Joe Dante suggests that the film is based on Stephen Vincent Benét’s 1937 short story By the Waters of Babylon. Of course, Corman wouldn’t secure the rights to a story, as that cost money, but it is easy to see that By the Waters of Babylon served as a blueprint for Teenage Caveman. While not a straight adaptation, the themes and the basic plot of both are the same, the language is very similar and the two works have too many details in common for it to be a coincidence.

By the Waters of Babylon is a short short narrated by a young man called John, son of John, the son of a priest, himself set to become a priest, who lives in a prehistoric-type world. As part of his rite to become a priest, he sets off to the East, to the Place of the Gods, beyond the river, to which it is forbidden to go, as it is a poisonous place riddled with ghosts and demons. So says the Law. The story differs from the film inasmuch as the reader is made aware from the beginning that it is set in a post-apocalyptic world, and that the Place of the Gods is a ruined and abandoned New York. The story was written as a reaction to the bombing of Guernica during the Spanish civil war, years prior to the invention of the nuclear bomb, however the descriptions of the post-apocalyptic world eerily resembles later stories set in the aftermath of a nuclear war – even though the mention of poisonuos grounds may refer to mustard gas and biological warfare. In Benét’s story, John and others of his tribe are able to read, and use knowledge from “the gods”, found in books, to improve their lives – there are mentions of spinning jennys and some resemblance of modern medicine learned from books. In the story, John enters the ruined New York and sleeps in one of the old buildings, where he has a vision of New York before the fall, and a vision of how mankind’s hubris and knowledge led to a great war which devastated the world. He realises that the “gods” were not gods at all, but humans, like himself. When he returns to his tribe, he asks his father permission to reveal the truth to his tribe, whereby his father replies that perhaps the laws were formed for a reason – and that too much knowledge might lead humanity down the path of their ancestors. However, John has determined that when he becomes the high priest, his tribe will go into the old city and learn the secrets of the men who came before: “We must build again”.

By the Waters of Babylon is quite a well-known story and has been included in many anthologies – it is also a very good story. However, from a cinematic point of view it is problematic, as very little happens in it. Across its eight or so pages, there are descriptions of John’s journey to the Place of the Gods (rather uneventful), his descriptions of the ruined city and a (rather uneventful) run-in with a pack of wild dogs. Much of the text is concerned with John’s inner monologue. Furthermore, for the purposes of AIP and Roger Corman, the story is quite unfilmable because of its vivid depictions of a ruined New York, requiring a budget far beyond the reach of the director/producer.

Corman turned over the story for adaptation to R. Wright Campbell, one of his go-to writers. Campbell was not quite in the same league as Corman’s other staple writer Charles Griffith, but he was capable of turning out rather good stuff from time to time, and even earned an Oscar nod for his collaboration on the Lon Chaney biopic The Man of a Thousand Faces (1958). Campbell’s job, then, was to take the essence of the short story, flesh it out into a plot for a feature film and make it filmable on a budget of pocket money.

The result is a mixed bag. In contrast to many other caveman pictures of the era, Campbell does a fair job of depicting the tribe’s traditions and belief systems, partly borrowed from the story, but much of it from his own pen. However, his attempts at putting these traditions and beliefs into a story inhabited by living beings often fall flat, rendering many of the characters simply mouthpieces for ideologies or vessels for propelling the plot forward in often extremely contrived and illogical ways. Such as when Frank DeKova convinces the tribe to kill the stranger just because they have never seen a man riding a horse before: “A man on top of an animal? There is no such thing!” The film’s depiction of the laws also become ever more muddled as the plot wears on. Considering the villagers’ reverence for the law, it is astounding how often the law is broken, ignored or even changed. The whole point of the film is that it is forbidden to go beyond the river, and that’s why Robert Vaughn’s quest is the centrepiece of the movie. But soon people are crossing the river back and forth en masse. Vaughn’s punishment, the silent treatment, last just about five seconds, before everyone is yapping at him again, with no consequence. And so forth.

Campbell also has trouble filling out the plot between start and end, resulting in endless scenes of people running up and down Bronson Canyon and the forests of Arcadia, California, in loincloths and sandals made out of car tires. Pretty much everything that goes on back at the tribe is Campbell’s creation. He has added the villain DeKova, Vaughn’s girlfriend (who is a wholly redundant character), the power struggle within the tribe, and of course the “monster”. This was probably a selling point to AIP execs James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff: a philosophical rumination about man’s striving for knowledge and progress as the inevitable agent for humankind’s own destruction, set in a post-apocalyptic caveman world would probably have been a hard sell. Stick a monster and a naked girl in the mix, and Nicholson could make a selling poster, and often that was all that mattered. The scene in which Darah Marshall is bathing in the nude is in the movie solely for AIP to be able to put it on the poster and in the trailer. Campbell and Corman have also added dinosaurs, which makes no sense (even if the script tries to justify it with the idea that radiation made reptiles grow large). The poster featured Vaughn battling a dinosaur, but the dinosaurs hardly even register in the film. We also get a short cameo from monster maker Paul Blaisdell’s She Creature (1957). Geography is a problem, as it always is in these low-budget films. There is no sense of direction or distance. One minute we are among the rocks of Bronson Canyon, the other in an arboretum, and it’s impossible to tell whether the characters have travelled for days or minutes. At one point Vaughn has set off beyond the river hours (or even days?) before his father goes after him, and it takes DeKova and his men hours(?) to set after them – but they all converge at the exact same spot at the exact same time.

Then there’s the “monster”, the God that Kills With its Touch. This is one of AIP’s more ridiculous creatures, looking like some sort of giant rodent. In fact, the creature is a human in a radiation suit, as explained by the closing narration. However, it is nowhere explained why they made radiation suits that looked like giant rodents covered with twigs and moss. The narration also stated that the ancient humans tried from time to time to make contact with the cavemen, but that “they were afraid of us”. Gee, you think it might have helped if you took off your rodent head? The closing narration also makes little sense to me, but perhaps you can explain it in the comments: The ancient man apparently wore the suit to protect himself from radiation. Still, he claims to have been radioactive himself, as the radiation has given him long life, and in the past at least, he has been known as the god that kills with its touch. The narration now says that the radiation has worn off. But if that is the case, then why the need for the suit? Help, anyone?

I haven’t found any reliable information on who designed and made the monster suit. Many sources mention AIP’s go-to monster maker Paul Blaisdell, but Blaisdell was usually credited when he made the monster suits, and almost always played the monster himself. However, he is not credited in Teenage Caveman. IMDb lists him as the uncredited designer of the “beastman costume”, but this most likely refers to the short cameo from the She Creature. Teenage Caveman is only mentioned in passing in Randy Palmer’s biography Paul Blaisdell, Monster Maker, and the book only states that a clip from The She Creature was reused in the movie, and doesn’t discuss the main monster at all, which more or less confirms that it was not made by Blaisdell. Furthermore the “God that Kills With Its Touch” doesn’t look at all like a Blaisdell creation. Marjorie Corso is credited for costumes, but she was usually involved in wardrobe and not special effects costumes. It is possible that the “monster” was created by props master Karl Brainard. The same costume was reused in the Corman-produced Night of the Blood Beast (1958, review).

Several movies had already touched upon the theme of a post-apocalyptic world in the wake of a nuclear war. Many of them toyed with the idea of mankind bombing itself back to the Stone Age: in Rocketship X-M (1950, review), astrounauts find an abandoned Martian civilisation, devolved into mutant cavemen. In World Without End (1956, review), accidental time travellers come across societies divided into cave men above ground and civilisation below (taking a page from H.G. Wells). Teenage Caveman perhaps mostly resembles Captive Women (1952, review), set in a post-apocalyptic New York, which has devolved into a sort of Medieval feudal society. The twist of the narrator in Teenage Caveman is that the film actually depicts our past, and suggests that humankind’s cycle of hubris and destruction is eternal (of course, from a historical point of view this makes no sense, even if it is a strong metaphor.

Teenage Caveman has a reputation as one of Roger Corman’s worst movies, and there are certainly numerous flaws to point out. The cavemen speak in almost Shakespearean soliloquys (lifted from the story), but haven’t figured out how to use names or create bows and arrows (the scene is which Vaughn invents the bow and arrow when he realises a tree twig is springy is one of the most unintentionally hilarious in the film). There’s a dime store prehistoric look to the whole movie, with loincloths looking like they were bought at a costume shop, extremely bad dinosaur puppets (plus the ubiquitous slurpasaur footage from One Million B.C.), a terrible-looking bear (Beach Dickerson in a suit), and the most unconvincing hunting bow in film history. It looks like a toy made for a child, and poor Robert Vaughn must have let out a deep sigh when it was handed to him. The story is repetitive and confusing, and the character motivations remain hazy throughout the film.

Corman was often able to snatch up talented actors who were willing to work for minimum wages, and Robert Vaughn was another find, here in his first lead. Some have suggested Vaughn was miscast, because he is a thinking actor, rather than the more simple action-oriented actor often cast in these kind of roles. I’m not sure that nails it, as his character is supposed to be a thinking character. Closer to the point, perhaps, is that Vaughn is too good an actor for the role, and his presence shines a light on the clunkiness of the movie, in a way that the performances of Frank DeKova, Leslie Bradley and Darah Marshall do not. You can make the point, however, that Vaughn was a tad too old for the role at 26.

In an interview with Tom Weaver, Corman staple Ed Nelson shared a number of entertaining stories from the shooting, such as the fact that Corman had wrangled up a dime store dog wrangler with poorly trained dogs, that he set upon a a terrified, half-naked Nelson. However, the dogs were so scared of Nelson that they scattered in all directions, and he had to forcibly hold on to them in order to make it look like they were attacking him. Another potentially dangerous incident involved Beach Dickerson (who played four “characters” in the film, three of which die, and the fourth one plays drums at the funeral of the first one.) This time he was playing the impossible man on a horse, and Corman wanted him to fall off the animal. When Dickerson pointed out that maybe this was the job for a stuntman, Corman opined that Dickerson was able to fall off a horse just as well as anyone. Fortunately, he was not hurt.

Veteran photographer Floyd Crosby was usually able to bring a certain level of sophistication to Corman’s movies, but seeing as Teenage Caveman was filmed entirely on location in a very brief period of time, even Crosby isn’t able to squeeze much of the the visuals in the film. AIP house composer Albert Glasser’s orginal score is, as usual, a highlight of the film. Not special in any way, but as it is an original and not canned music, it supports the movie well.

Roger Corman always made movies with interesting ideas and with at least an attempt to actually say something, and Teenage Caveman is no exception. Corman was particularly proud of the ending of Teenage Caveman, standing by the movie despite its flaws. And yes, the idea and the sentiment are good, but handled badly. Just the fact that Corman thought he needed a closing narration in order to explain himself is reason for caution. Often a sprightly script, a good idea, decent acting and Corman’s efficient direction helped bring enough quality to his films that most of his 50s SF movies remain highly watchable and stand out among most of their ultra-cheap B-movie peers. Unfortunately, Teenage Caveman was one of the few films in which Corman dropped the ball. It has its moments, and it is certainly watchable and even entertaining in its own, silly way, but it just doesn’t gel.

Reception & Legacy

Teenage Caveman premiered in July, 1958, on a double bill with Herman Cohen’s How to Make a Monster (review), and, as most of AIP’s exploitation movies, made a decent profit.

The film received a mixed reception in the trade press. The Film Bulletin was mildly positive, focusing mainly on the movie’s ballyhoo potentials for theatres, noting that AIP “successfully continues the parade of big-screen comic books with built-in soda fountain appeal”. Both the Film Bulletin and Variety noted positively the twist ending. Powr in Variety said: “This is obviously a low-budget picture, and in theatrical terms it doesn’t always sustain, but the “message” is handled with restraint and good taste, and gives substance to the production”. Harrison’s Reports wasn’t quite as positive, opining the film “might have some attraction for children”, but that adults need not bother. The magazine also noted the twist ending, but thought “this message of warning does not come through the hodge-podge screenplay with any appreciable force”.

The often cranky John Baxter in his book Science Fiction in the Cinema was surprisingly positive, calling Teenage Caveman a “clever Z picture with some ingenious twists”. Bill Warren in his book Keep Watching the Skies gives the film points for “a certain seriousness of purpose and a relatively intelligent approach” to the tribal rituals, but nevertheless names it one of Corman’s feebler efforts, “with a heavy air of cheapness and an abundance of stock footage”. TV Guide called it a “well-conceived cheapie” that “isn’t even half-bad”.

Today, Teenage Caveman has a 3.5/10 rating on IMDb and a 2.5/5 rating on Letterboxd.

Teenage Caveman has a very mixed reputation among online critics. DVD Savant Glenn Erickson calls the script “a gem that has relevance even without the last-second twist surprise” and compares it favourably to M. Night Shyamalan’s The Village (2004), with a similar twist ending (his review was written in 2006, so he can be excused for the Shyamalan-bashing, which has since become incredibly trite). Mitch Lovell at The Video Vacuum delivers another positive review with a 3/5 star rating, calling the movie “one of the better Roger Corman efforts from the ‘50s”.

Richard Scheib at Moria is sort of glass half full/half empty about it all in his 2/5 star review: “While Teenage Caveman is an exploitation movie, it has an inventive script. […] Unfortunately, the film’s ideas remain far superior to Roger Corman’s execution of them. It is an A-budget idea trapped in the guise of a Z-budget film.” Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings concurs: “It’s easy to poke fun at the obvious cheapness and the silliness of a lot of this movie, but if you consider that it was a caveman epic, it was quite ambitious in some ways. It’s actually trying to make some real commentary on the nature of law and tradition, and I can’t help but admire the intention; if only the script weren’t so preachily verbose about it, it might have worked better. The fact that the story just seems to wander from scene to scene doesn’t help much, either; it really could have used a couple of rewrites.” The only one of my go-to critics who really doesn’t like the movie is Kevin Lyons at The EOFFTV Review: “Teenage Cave Man is a twist ending in desperate need of a plot. […] while you may not see the ending coming it won’t be entirely satisfactory, like to evoke a groan rather than a feeling of awe. As a result, it’s a dreary affair”.

Teenage Caveman was featured on the rifftrax TV show Mystery Science Theater 3000 in 1991, which has added to its reputation as a terrible movie. Robert Vaughn has been “quoted” (mostly without any information on the source) as calling it the worst movie he ever made and “one of the best worst movies of all time”. However, considering some of the films he appeared in the 80s and 90s, Teenage Caveman can hardly be ranked as the worst. Many sources also claim that Vaughn didn’t like to talk about his involment with the film. However, in an interview with Tom Weaver, he quickly debunks this myth, and says that he never had any regrets about appearing in the movie, and that he actually rather liked the script: “Oh, I’ve gotten more mileage out of that picture, in terms of talking about it, than any other picture I’ve DONE, practically […] I’ve been questioned about Teenage Caveman many times over the years, and it’s always good copy”. He adds that it gave him his biggest paycheck to date, which enabled him to buy his first new car. As stated, Corman defended his vision, and thought the film could have been “genuinely good”, had he only had more time and money to make ut.

In 2001 effects wizard Stan Winston, Sam Arkoff’s son Lou and actress/producer Colleen Camp produced five TV movies under the banner “Creature Features” for Cinemax, all of them remakes – or really reimaginings – of old AIP horror/SF movies. One of them was Teenage Caveman, however little remains in the 2002 version of the story, except the basic premise of caveman teenagers leaving their tribe to find a better life. The movie was directed by the controversial Larry Clark and is mostly set in a post-apocalyptic Seattle, and mostly focuses on teen sex, until a virus turns them into pumped-up hulks. It’s IMDb score is even lower than the original’s.

Cast & Crew

Roger Corman needs no introduction to readers of this blog, and this is the n:th Corman film I’m reviewing, so anyone interested in a broader biography on the man can easily find one through the search function. Suffice to say that between 1954 and 1958, Corman had produced 20-something films, and had directed well over half of them. Corman was getting confident in the director’s chair, and subsequently also more ambitious as a director.

Corman’s credo was that he could make movies that could compete with major studio pictures at the box office on a fraction of their budgets through economical filmmaking and through cutting out basically all overhead costs. In this he succeeded. Granted, he didn’t quite play by the rules. He kept his costs down by relying on a tight-knit team of associates who would more or less pitch in for free whenever needed, by underpaying his cast and crew and by ignoring pretty much all health and safety guidelines of the movie business. But he also had a keen eye for talent, from securing talented writers and creative special effects designers to being able to spot from a mile away actors that had that special something. By 1958 he had already worked with future stars like Lee Van Cleef, Peter Graves, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn and Jack Nicholson.

Corman had cut his teeth on westerns and science fiction monster movies, pictures in popular genres that could be made on his meagre AIP shooting budgets of $100,000. His growing confidence can be seen in several pictures he produced and and directed in 1957/58. He took a stab at historical epics with The Saga of the Viking Women … etc and Teenage Caveman. And he also moved into the gangster and crime genres with films that were more focused on drama than on gimmicks and action with films like The Cry Baby Killer, I, Mobster, and not least Machine-Gun Kelly, the first film for which he received genuine interest from critics. At the end of the decade he was confident enough to give free rein to the dark, quirky humour he shared with screenwriter Charles Griffith in movies like A Bucket of Blood (1959) and the lauded cult classic The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). which he would perfect in his extremely fruitful 60s collaboration with Vincent Price on the works of Edgar Allan Poe, a movie cycle in which Corman emerged fully as a low-budget auteur in his own right. Another passion project was The Intruder (1962), starring a mesmerising William Shatner – a film about segregation in the US shot guerilla-style in Missouri. This was perhaps Corman’s most personal film, and had it been as commercially successful as his other movies, it might have forever changed the path of his career.

Robert Wright Campbell was a New Jersey-born screenwriter and later novelist. One IMDb user credits him with originating the use of the phrase “La-La Land” as pertaining to Los Angeles. While this is decidedly not true, he did publish as series of detecive novels set in Los Angeles using the phrase in the title, which may or may not have helped popularise its use.

Campbell got his first screenwriting job by Roger Corman for Corman’s directorial debut Five Guns West (1955), after which he scripted a couple of low-budget movies for Universal. He got what seemed like a big break when he was asked to pen the script for the studio’s biopic of legendary horror actor Lon Chaney, The Man of a Thousand Faces (1957). The producers wanted to hire a young writer who wouldn’t be bogged down by nostalgia. However, the studio wasn’t happy with the finished product, and the script was heavily re-written by other writers. Nevertheless, Campbell received credit, and was subsequently honoured when the screenplay got an Oscar nomination. Unfortunately, this also marked the end of Campbell’s association with Universal, and he struggled on, freelancing for smaller studios throughout the late 50s and 60s. Over half of his subsequent movie scripts were for Corman, starting with Machine-Gun Kelly (1958) and ending with The Secret Invasion (1964). He also wrote, among others, Teenage Caveman (1958) and The Masque of Red Death (1964). He also wrote the biker movie Hells Angels on Wheels, riding on the success of Corman’s The Wild Angels (1966). Initially, Hells Angels on Wheels was announced as an AIP project, and features much of Corman’s usual cast and crew, but ended up being produced by Joe Solomon’s Fanfare Films. Campbell also co-wrote the family friendly SF movie Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (1969). After this, Campbell embarked on a reasonably successful career as an author of mainly crime and detective stories.

While his name might not mean all that much to a younger generation, to folks born in the 40s and 50s, Robert Vaughn was one of the biggest TV stars on the planet, primarily thanks to his turn as one of the co-leads in the television secret agent show The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964-1968), alongside David McCallum. However, his road to stardom was not straight as an arrow, despite being born into a family of actors, and beginning as a child actor on the radio as early as the age of five. He briefly studied journalism before settling on theatre studies instead, and made his TV debut in 1955, after which he appeared mainly as a guest actor on TV shows and in movie bit-parts. His lead in Roger Corman’s Teenage Caveman (1958) was his first big role, but it was hardly on the strength of this that he was cast in a significant supporting role in the Paul Newman vehicle The Young Philadelphians (1959), which earned him an Oscar nomination. The next year he was cast as one of the seven gunslingers in The Magnificent Seven.

However, despite making waves in these two films, Vaughn struggled to make the A-list, and primarily busied himself with guest star spots in TV shows, until he landed a co-lead in the military show The Lieutenant in 1963. The show was no great hit, but it was through it that he found himself cast in a new James Bond-inspired TV series starring as Napoleon Solo, agent of the UN-affiliated organisation U.N.C.L.E., alongside sidekick, later equal partner Ilya Kuryakin (David McCallum). The Man from U.N.C.L.E. became an international phenomenon, even behind the Iron Curtain, and was one of the biggest TV series of the 60s, spawning both films and spinoff TV shows, catapulting Vaughn and McCallum into superstardom. The show earned 16 Emmy nominations and won a BAFTA for best TV show in 1966.

Vaughn has said that the show turned him from a working actor into a negotiating actor, and he once again set his eyes on a career in films. It began with a bang, as Vaughn was cast as Sen. Walter Chalmers in the Steve McQueen vehicle Bullitt (1968), and immediately won a Golden Globe for best supporting actor. However, despite appearing high up in the billing in A-list movies, his film career once again refused to quite take off. Of his later film roles, he is perhaps best remembered for being one many stars in the disaster film The Towering Inferno (1974). He gradually segued back into TV, however, mixing his small screen appearances with movie work. While always in demand as an actor, and never losing his marquee appeal, Vaughn’s status as an A-list draw diminished throughout the 80s and 90s. However, in the 2000s, he found a new audience, much like his former co-star David McCallum as “Ducky” in NCIS, when he was cast as the veteran grifter Albert Stroller in the BBC hit show Hustle (2004-2012), which just so happens to be one of my favourite TV series.

Robert Vaughn also became something of a science fiction staple, appearing in close to 20 SF movies, both relatively good ones and a good number of clunky cheapos. Worthy of mention are at least Teenage Caveman (1958), The Mind of Mr. Soames (1970), The Lucifer Complex (1978, currently holding a 2.6/10 IMDb rating), Virus/Fukkatsu no hi (1980), Hangar 18 (1980), the fun Roger Corman Star Wars ripoff Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), Superman III (1983) and Joe’s Apartment (1996). He also starred in the spy-fi series The Protectors (1972-1974).

Vaughn was active in the Democratic party, and was described as belonging to the left flank of the party, although he didn’t support communism. He was the first high-profile actor in Hollywood to take a stand against the Vietnam war. In 1972 he published his doctoral thesis on the impact McCarthyism had on US show business, called Only Victims: A Study of Show Business Blacklisting, which has been called “the most complete and intelligent treatment of the virulent practice of blacklisting now available”. Vaughn passed away in 2016.

Leslie Bradley, who plays Vaughn’s father in Teenage Caveman (1958) was an in-demand supporting actor born in England with an accent and face that made him popular with casting agents for period dramas. He is perhaps best known for his turn alongside Burt Lancaster in The Crimson Pirate. He also appeared in the musical time travel comedy Time Flies (1955, review) as Sir Walter Raleigh and teamed up with Corman in Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957, review).

Frank DeKova was a prolific bit-part actor, who was occasionally seen in larger roles, often playing heavies in westerns and crime films, and his dark features made him popular for “ethnic” roles. Jonathan Haze, Beach Dickerson and Ed Nelson were part of Corman’s troupe, and have been covered rather extensively elsewhere on this blog. The same goes for science fiction staple Robert Shayne, who at one time could command lead roles, but who was by 1958 confined to merely bit-parts.

We have mentioned cinematographer Floyd Crosby several times on Scifist, but I haven’t yet written any biographical notes on him. Crosby was an interesting cinematographer, who won awards and could have gone on to become one of the top DPs in Hollywood, but instead preferred to work for independent producers and low-budget productions.

Crosby studied cinematography in the 20s, and one of his first jobs was as cameraman for marine biologist William Beebe to Haiti in 1927. The expedition established him as an ace documentary photographer, and this led him to be hired as the cinematographer on the docufiction film Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931), an early sound fim by F.W. Murnau. This was Crosby’s debut feature, and it immediately earned him an Oscar for best cinematography. Crosby spent the following decades mostly filming documentaries, infotainment and educational films, but did do the odd feature film here and there for different studios. A turning point in his career came when he was hired to shoot Fred Zinnemann’s lauded western High Noon (1952), which received four Oscars and a Golden Globe for Crosby. He made another A-picture with Zinnemann, From Here to Eternity (1953), but soon grew disillusioned with big-budget filmmaking, and the way studio politics influenced the filmmaking. However, the early 50s marked Crosby’s definitive shift from documentary filmmaking to feature films – he just preferred to work on smaller, independently produced pictures for the rest of his career.

Crosby’s first picture for Roger Corman was Monster from the Ocean Floor (1954, review). Despite the low budget and the questionable result, Crosby must have seen something he liked in the way the young producer worked, and in the modus operandi of what would eventually become American International Pictures: a fast shooting schedule, a complete lack of overhead costs, bureaucracy, studio meddling, and a willingsness to give the producers and directors free hands to experiment, make things up as they went along and focus on the essential: making the movies. One imagines that he found something of a kindred soul in Corman, a producer/director who cared about the end result of the pictures he was making and had a love for filmmaking, but didn’t take his “art” too seriously. As a director, Corman quickly learned how to make the most out of limited setups, sets and locations, and probably learned much from Crosby about how one could create dynamic, movement and tension in single shots by using camera movement and the movement of the actors, rather than having to do multiple setups. Here, Crosby’s long long experience of documentary filmmaking undoubtedly brought much to the table.

Crosby became Corman’s cinematographer of choice, and together they made over 20 films, including Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957, review), War of the Satellites (1958, review), Teenage Caveman (1958), Machine-Gun Kelly (1958), I, Mobster (1959), all of Corman’s seven Edgar Allan Poe films between 1960 and 1963, as well as The Terror (1963) and X (1963). He also worked for other AIP producers and directors, and became the principal photographer on the studio’s later beach party movies. But he wasn’t limited to AIP, but also worked extensively for other studios, like United Artists, Allied Artists and API, making both movies of questionable quality like W. Lee Wilder’s The Snow Creature (1953, review) and better one, like Edward Smalls’ The Naked Streets (1955) and Robert Mitchum’s The Wonderful Country (1959). Apart from being a cinematographer, Floyd Crosby is also known as the father of musician David Crosby.

Janne Wass

Teenage Caveman. 1958, USA. Directed by Roger Corman. Written by R. Wright Campbell. Based on the short story “By the River of Babylon” by Stephen Vincent Benét. Starring: Robert Vaughn, Leslie Bradley, Frank DeKova, Darah Marshall, Charles Thompson, June Jocelyn, Jonathan Haze, Beach Dickerson, Ed Nelson, Robert Shayne, Marshall Bradford, Joseph Hamilton. Music: Albert Glasser. Cinematography: Floyd Crosby. Editing: Irene Morra. Produced by Roger Corman for Malibu Productions & American International Pictures.

Leave a comment