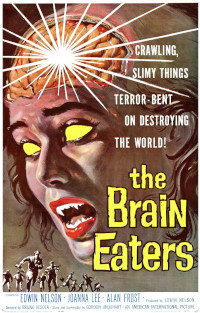

Small-town scientists investigate a strange metallic cone while the townspeople get body-snatched by parasites. An unauthorised ripoff of Robert Heinlein’s “The Puppet People”, this 1958 AIP low-budget clunker directed by Bruno VeSota is inept, but has its moments. 4/10

The Brain Eaters. 1958, USA. Directed by Bruno VeSota. Written by Gordon Urquhart & Bruno VeSota. Based on novel by Robert Heinlein. Starring: Ed Nelson, Alan Jay Factor, Cornelius Keefe, Joanna Lee, Leonard Nimoy. Produced by Ed Nelson & Roger Corman. IMDb: 4.4/10. Letterboxd: 2.5/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Strange deaths occur in the small town of Riverdale, Illinois, after a strange conical object appears in the forest. Senator Walter K. Powers (Cornelius Keefe) will have none of this alien mumbo jumbo, and sets out to investigate. At Riverdale, he is met by the local scientists, Dr. Kettering (Ed Nelson), Dr. Wyler (David Hughes), Glenn Cameron, the missing mayor’s son (Alan Jay Factor), and Alice Summers, the missing mayor’s secretary (Joanna Lee) (also Kettering’s girlfriend), as well as Glenn’s wife Elaine (Jody Fair). Kettering and Wyler explains that the weird cone is indestructible, and only has one entrance, a small circular opening in the side. Spurred on by Senator Powers, who wants action, Kettering enters the cone. A long time passes, and when he returns, he informs the others that he found nothing – nothing but endless tunnels of tubing. However, the team get word that the mayor (Orville Sherman) has returned. When the team confront the mayor, he is visibly upset and clearly not himself. When he pulls a gun on the team, they gun him down. An autopsy finds a small alien parasite attached to the base of his neck. Kettering explains that the parasite not only slowly kills its subjects, but also controls their brains.

Thus begins The Brain Eaters from 1958, produced by Ed Nelson and Roger Corman, and directed by Corman staple Bruno VeSota, on a very modest budget of $26,000. The script by Gordon Urquhart was an unauthorized adaptation of Robert Heinlein’s 1951 novel The Puppet Masters. The film is perhaps best remembered today for featuring Mr. Spock, Leonard Nimoy, in a small but memorable role.

Soon the town is crawling with parasites, hindering Sen. Powers’ attempts at contacting Washington and sending in the national guard. After failed attempts at telegraphing and telephoning, the team realise they need to take on the alien cone themselves. However, suddenly a dying man gets spat out by the dying cone. This is Professor Helsingman (Saul Bronson), one of two scientist gone missing years ago, the other being Nimoy’s character Professor Cole. New information gleaned from Helsingman before he dies reveals that the parasites are not actually aliens, but prehistoric creatures that have not landed as much as burrowed up from the bowels of the Earth.

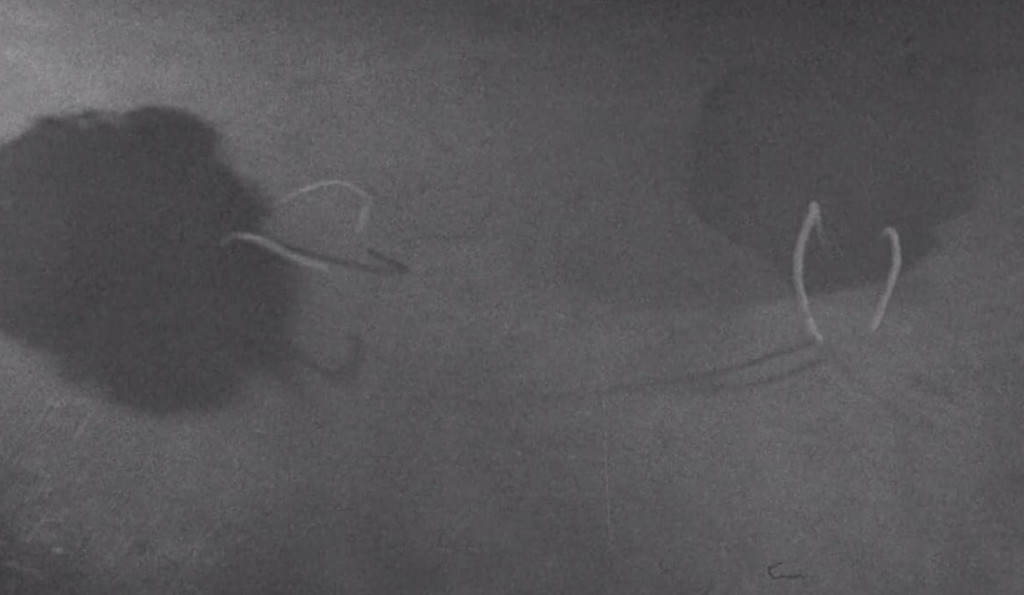

Kettering and Powers take another stab at exploring the cone, this time finding a foggy room with a bearded, old Nimoy sitting on a throne surrounded by tubes filled with parasites. He explains that he and the parasites represent a higher order of social interaction, and will free mankind from suffering and pain, through removing free will and subjugating ourselves to the parasites. Of course, our thorough-bred Americans will never subjugate themselves to any commie parasites, so they shoot Nimoy and crawl back outside. Here Kettering comes up with a rather complicated plan to electrocute the cone, involving harpoon guns and high-tension wires. However, at the last minute it is revealed that the parasites have also body-snatched Kettering’s girlfriend Alice, whom he stupidly tries to save, before she shoots him and Glenn electrocutes them both along with the communist parasites.

Background & Analysis

According to actor Ed Nelson, in an interview with Tom Weaver, the origins of The Brain Eaters lie with Bruno VeSota, a supporting and bit-part actor who was a staple in Roger Corman’s low-budget movies. VeSota had come up with a story for a film that he wanted to direct, and approached Roger Corman with it. The Brain Eaters was not an official American International Pictures production, and was made for Corman’s Malibu Productions, which allotted it a measly budget of $26,000 – Corman made a handsome profit when he sold the movie to AIP for $200,000. But because of the low budget, it couldn’t be done as a union picture, which meant that Corman couldn’t produce it. Instead he asked another of his staple actors, Ed Nelson, if he would consider acting as producer.

Nelson was primarily an actor, but as most of the Corman inner circle, he had also worked on the production side of Corman’s movies. Furthermore, he had actually studied production, and had helped out Corman a lot with production issues on his movies. Nelson agreed, and a fellow named Gordon Urquhart was asked to write a script from VeSota’s story. Little is known about Urquhart, other than the fact that he was an old friend of VeSota’s, and had probably worked with him in Chicago.

The Brain Eaters was primarily filmed in and around Ed Nelson’s hometown of Pomona, California, and Nelson tells Tom Weaver that he was only able to make the movie thanks to help with locations, sets and props from the town’s mayor, its police department and other local authorities, businesses and inhabitants. The space ship/burrower stood thirty feet tall and was constructed from wood and aluminium sheets by Nelson’s neighbour, who was a carpenter. Only one half of it was made, and when they were supposed to film it from the other side, they just turned it around. The scene inside the the ship was filmed in Nelson’s garage with the lights turned out and a single light pointed at Leonard Nimoy, who played the old man. Nimoy was a friend of Nelson’s, as were most of the cast and crew, and took the job for a salary of $45 – which Nelson confesses that he never paid Nimoy. The brain eaters themselved were wind-up toys that Nelson glued pieces from a fur coat on, and attached pipe cleaners as antannae. According to Nelson, the cast and crew often worked 12-hour days, but he says he kept people happy by having good food and beer on set.

When the film premiered, SF author Robert A. Heinlein caught wind of the movie and realized it bore striking resemblances to his 1951 novel The Puppet Masters. To be fair, the plot of the film is quite different from the novel, which takes place in the future and follows a secret agent and his team fighting off mind-controlling alien blobs from Saturn’s moon Titan. However, there’s enough similarities to eradicate any doubt that the script wouldn’t have been inspired by Heinlein’s book. Both book and film feature parasites that arrive by ship and attach themselves to the backs of people and take over their minds. The puppet people can be distinguished by the humps on their backs. In both stories the parasites form a sort of hive mind and plan to take over the Earth and turn it into the McCarthyist lobby’s nightmarish image of what a socialist world would look like: a world of mindless drones, devoid of all emotion, moral and individuality.

Heinlein sued the production company. Roger Corman stated that he had not read Heinlein’s book when he made the film, but upon reading it said that he could not deny the similarities. Ed Nelson, the producer, told Tom Weaver that he had never read the novel either. Screenwriter Gordon Urquhart said that he merely expanded on the story handed to him by Bruno VeSota. VeSota also denied having any knowledge of Heinlein’s book, however because it was VeSota that came up with the original story, it is almost certain that VeSota not only was aware of the novel, but knowingly used its premise for the base of his screen story – changing it up enough so that it didn’t look like a direct ripoff. The matter was eventually settled out of court, and despite getting monetary compensation, Heinlein demanded that his name be not attached with the film in any way.

Thematically, the film is a callback to the red scare SF movies of the early and mid-50s, in which alien body snatchers are substitutes for communist infiltration of the US. However, it doesn’t feel like the film has originated in a strong urge to deliver a message, and the scene in which Leonard Nimoy delivers his speech about surrendering out minds to the furry slippers comes across more as a trope than anything that someone has put any decent amount of thought into. Rather, the focus is on the horror and mystery tropes – the characters spend most of the film investigating what the odd cone is and who its body-snatching inhabitants are. The revelation in the end that the furry slippers are communist infiltrators is less ideologically charged than it is simply a solution to the film’s mystery.

Plot-wise, the film’s narrative is jumpy and episodic, catapulting itself from one set-piece to the next without a clear dramatic arc. It lumbers from non-descript rooms to forested roads and parks, without any sense of distance, passage of time or geography. Bill Warren has described The Brain Eaters as the best of Bruno VeSota’s three directorial efforts (excluding Dementia [1955], which he co-directed with John Parker). And there is, at least, an effort here to create atmosphere. In the scenes where the parasites attack, VeSota often tilts the camera in order to create a sense of unease, and there are a couple of uses of imaginative camera angles. But apart from this, the direction is flat and undynamic, and not helped by the shoddy effects and the wooden acting.

The whole thing is rather silly and derivative, and the idea of the parasites being living fossiles from 200 million years ago, just now deciding to hit the surface and enslave humanity, is a hilariously contrived idea, probably dreamed up by VeSota as a way to try to avoid plagiarism accusations. The whole movie feels like an amateur attempt at emulating Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

The acting is hardly of the highest class, but it isn’t the acting that is this film’s biggest problem. Ed Nelson was a decent enough actor, and he is credible in the heroic lead. Unfortunately the same can not be said for the female lead, Joanna Lee, whose biggest claim to fame is playing one of the aliens in Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957, review). She later had a better career as a screenwriter and producer. David Hughes as Dr. Wyler is good, despite this being his only film role, and Alan Jay Factor adequate as Glenn Cameron. Cornelius Keefe plays the senator loud and large, as the role calls for. Jody Fair has a good presence, but gets little to do and Phil Posner feels way to hapless to be a sheriff. Veteran character actor Orville Sherman gives perhaps the film’s best performance as the possessed mayor. Leonard Nimoy is in the film for only a couple of minutes, and so obscured by facial hair that it’s difficult to say anything about his performance. Would it not be for his recogniseable voice, it would be hard to spot him.

Despite all its flaws, The Brain Eaters is a curiously engaging film, with a fast-moving plot and some actual tension and some instances with rather good atmosphere. Based as it is on Heinlein, it has at its core an interesting idea, even if it was worn out by 1958, when the communist alien mind control trope had become rather old hat. Best left, perhaps, to completists, but but a fun little watch if you should stumble upon it.

Reception & Legacy

The Brain Eaters premiered in September, 1958. It was produced and released simultaneously by AIP with Bert I. Gordon’s The Spider/Earth vs. the Spider (review), and even though they would not be put on the same bill, Powe in Variety noted the similarities, for example that both menaces were electrocuted in the end. In his review, he mentions that the films would not be booked together, “so the duplication of plot resolution will not be glaring, but indicate such features run short of potential”. However, he went on to say that The Brain Eaters “is well enough done as these horror films go, but this cycle appears to have reached the point of diminishing returns”. He further laboured the point that by the fall of 1958, low-budget science fiction/horror movies were becoming repetitive and programmatic, most of them using the same gimmicks; “Since much of this fantasy-fiction material is the same basis, it doesn’t make too much difference, except that these pictures are supported by largely the same audiences who notice such things”.

The critic in Harrison’s Reports wrote along the same lines: “In concept and treatment the story offers little that has not been done many times ever since pictures of this type came into vogue”, and opined that “only the indiscriminating will be impressed”. In the Hollywood Reporter, Jack Moffitt also called the film “routine”, but he gave it points for having the monsters come from underground and not from outer space.

In later reviews, Phil Hardy in his book The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies noted that the picture replaced Heinlein’s paranoia with “the more traditional, and less resonant, invasion by space monster theme”. He added: “Even this is erratically handled at best.” Bill Warren calls it “a dull little movie”, but adds that its sombre tone, the concept, the downbeat ending and its sincerity make it “watchable – though not exactly good”.

As of writing, The Brain Eaters has a 4.4/10 rating on IMDb and a 2.5/5 rating on Letterboxd (do ALL low-budget 50s SF movies have a 2.5/5 rating on Letterboxd?).

Kevin Lyons on the EOFFTV Review says: “The Brain Eaters is a muddled film that attempts some clumsy political satire but ends up a cheap and often cheerless film that harbours ambitions it could never have hoped to achieve.” Richard Scheib at Moria describes the film as a derivative and cheap alien body snatchers film that fails to generate the sense of paranoia that many of its better predecessors provided. However, he does note that Bruno VeSota occasionally drums up some atmospheric sequences, and gives it a (for Scheib) rather generous 2/5 star rating. Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster says: “at a little over an hour, it goes quickly and is pleasant enough, even though it never quite manages to find anything unique to throw in the mix”.

The movie had a lot of working titles, one of which was “Attack of the Brain Leeches”. However, Roger Corman liked the title so much that he reserved it for his own movie, which eventually became Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959).

Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters was eventually given an official adaptation in in 1994, under the same title. The low/mid-budget production starred Donald Sutherland and Eric Thal and was a very 90s movie. It released to mixed reviews and poor box office.

Cast & Crew

I have written at length about Roger Corman in previous posts. For a summation of his career, see my review of War of the Satellites (1958, review), and for a snapshot of where he was in 1958, see my previous post, Teenage Caveman (1958, review).

Ed Nelson was born in New Orleans in 1928 and studied radio and TV direction and production in New York, before returning to his hometown to work at a local TV station as assistant director, actor and writer. In 1957, Roger Corman arrived in New Orleans to film Swamp Women, and hired Nelson as an all-round handyman, from acting and location scouting to wrestling an alligator. Corman was impressed with Nelson, and convinced him to relocate to Los Angeles, where he became part of Corman’s inner circle of actors/crew who pitched in with a little bit of everything on Corman’s movies. For example, on Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957, review), Nelson played the giant crab and on The Brain Eaters (1958), he was the producer. However, unlike most of the other Corman entourage, like Beach Dickerson and Dick Miller, Nelson was also steadily employed as an actor outside of AIP, both in films and TV. He often had bit-parts in Corman’s movies, but his turn as lead hero in The Brain Eaters showed that he had the chops to pull off larger roles if given the chance.

In 1959, Nelson started getting a steady income from appearing as a guest actor on TV shows, and by the early 60s he was doing dozens of shows each year. He struck gold in 1964 he struck gold as he was cast as one of the principle cast on the soap opera Peyton Place (1964-1969). Over five years, he appeared in over 500 episodes of the incredibly successful show. Along with Barbara Parkins, he was the only actor to appear in both the first and the last episode, and to be credited in every episode. Nelson also appeared in Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review), The Brain Eaters (1958), Teenage Caveman (review), Night of the Blood Beast (1958, review), Deadly Weapon (1989) and Jackie Chan’s Who Am I? (1998).

Because The Brain Eaters was a non-union affair, Nelson couldn’t use Corman’s usual crew. That ruled out people like cinematographer Floyd Crosby, composer Albert Glasser, special effects creator/suit actor Paul Blaisdell and makeup artist Harry Thomas – people who often helped elevate a Corman production above its budget. The people credited on The Brain Eaters all have rather few credits. Editor Carlo Lodato and title designer Robert Balser are the ones with the longest credit sheets. Lodato worked as editor on 18 films, including some of Corman’s other work, and Balser carved out a career as an animator and director of animated films and TV series. For example, he was the animation director on Yellow Submarine (1968), the TV show Jackson 5ive (1971-1972), sequence director on The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1979), an animator on Heavy Metal (1981) and animation supervisor on The Charlie Brown and Snoopy Show (1985).

Director Bruno VeSota was a character actor and former TV director, who tried his hand at directing movies in Hollywood in the 50s. Born in 1922 in Chigaco, VeSota started his career on stage, where he both acted and directed, as well as in radio. He made his television debut in 1945, directing over 2000 live brodacast episodes and acted in over 200. He moved to Hollywood in 1952, where he started appearing in bit parts in movies and guest spots in TV. His association with Roger Corman started as early as 1954, when he appeared in the Corman-scripted The Fast and the Furious, and quickly became a Corman staple, appearing in 15 films produced and/or directed by the low-budget specialist. He directed three low-budget films: The Female Jungle (1955), The Brain Eaters (1958) and Invasion of the Star Creatures (1962). He also appeared in and co-directed the experimental horror film Dementia in 1955. Rotund and expressive VeSota was known for his colourful bit-parts, and sometimes got more substantial roles in Roger Corman’s movies. VeSota was also a colourful character in real life, and enjoyed a good prank. A less-than-healthy lifestyle led to his death of a heart attack in 1976, only 54 years old.

Bruno VeSota appeared in War of the Satellites (1958, review), The Wasp Woman (1959), Attack of the Giant Leeches (1959), Invasion of the Star Creatures (1962), Creature of the Walking Dead (1965), The Wild World of Batwoman (1966) and The Million Dollar Duck (1971). He directed the SF movies The Brain Eaters (1958) and Invasion of the Star Creatures (1962).

Most of the principle players in The Brain Eaters were bit-part players and few made any significant mark on film history, although some of them, like Cornelius Keefe, Robert Ball and Orville Sherman, had long careers as working actors, and were appreciated for their craft. Of the lead cast, the only who achieved any wider success was female lead Joanna Lee – however, as a writer and not as an actress. She appeared in 10 movies or TV shows between 1956 and 1961, and is probably best known for her role as Tanna the alien in Plan 9 from Outer Space (1958, review). However, as her acting career did not seem to be taking, off a serious car accident in 1961 finally pushed her to pursue a career in writing. She had a knack for comedies and children’s shows, and soon found herself writing for popular TV shows and animations, most famously The Flintstones (1962-1966), and is credited for creating the charactor The Great Gazoo. She was also a regular writer on Gilligan’s Island (1965-1966) and The Waltons (1973-1974), which earned her an Emmy win. In the mid-70s she started her own production company and started writing and producing TV movies. She directed over 150 episodes of Search for Tomorrow in 1983, one of the world’s longest-running soap operas, and then went on to write and produce Emmy-nominated afterschool specials.

However, the two most interesting characters in The Brain Eaters appear in minor roles: Leonard Nimoy and Hampton Fancher.

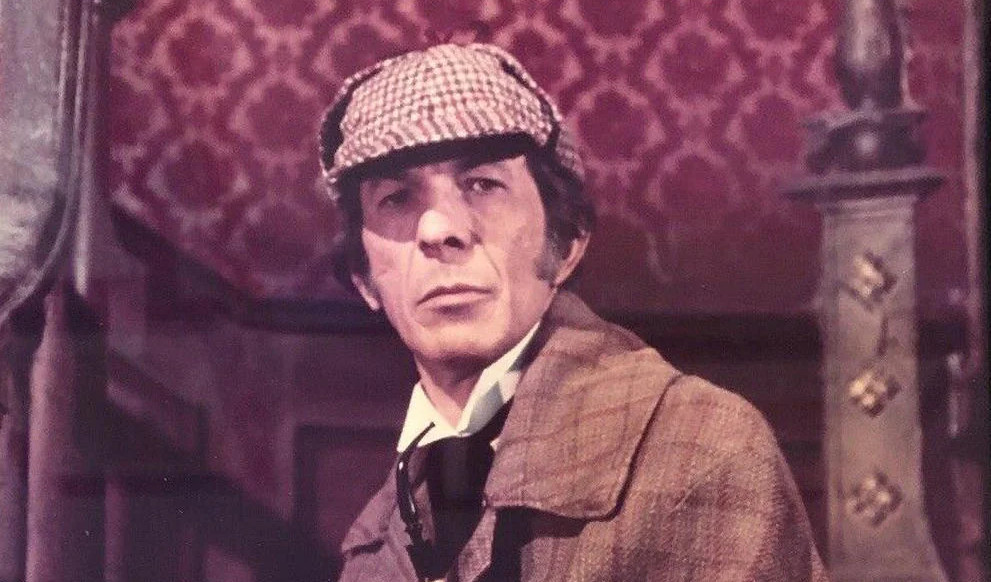

Leonard Nimoy, of course, needs no introduction to friends of science fiction. Born in Boston in 1931 to Ukrainian-Jewish immigrant parents, Nimoy started acting in community theatre at the age of eight, took acting classes and moved to Los Angeles in 1951. A serious actor, he adhered to Stanislavsky’s teachings and nursed hopes of becoming a leading man, but struggled to get substantial parts. Gradually realising his lanky build would prevent him from playing romantic leads, he instead focused on becoming a character actor. Working menial jobs between acting gigs, he soon settled into TV work as a guest actor, in between sparse movie appearances. His first brush with SF was as a Martian in an episode of the serial Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952), and he had a bit-part as an army officer in the classic Them! (1954, review).

In the 60s, Nimoy had started appearing in top-tier TV shows, often as heavies. One such was a 1964 episode of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., in which he had a scene opposite his future captain, William Shatner. In 1966 Nimoy was cast in a small science fiction show called Star Trek, as the half-Vulcan, half-human science officer Mr. Spock aboard the United Federation starship Enterprise, exploring strange new worlds and seeking out new life and new civilisations. As a science fiction show, Star Trek was unusual in that it was aimed at adults as well as the kiddie audience, and tackled literate and philosophical subjects, and its creator Gene Roddenberry imbued the series with an outspoken leftist ideology. Its often adult themes, packaged in a kiddie-friendly space adventure format, made it tricky for NBC to market, and after a flying start with the first few episodes, ratings started dwindling. The show struggled with average to poor viewer ratings, but its fans were rabidly protective of the series, a fact which saved it from cancellation both after the first and second seasons.

The show, which ran for three seasons between 1964 and 1969, catapulted Nimoy and his co-stars from obscurity to international fame, and Mr. Spock quickly became a cultural icon. Nimoy contributed much to the series and the development of the character – it was Nimoy who invented the Vulcan greeting, as well as the “Vulcan nerve pinch”. Nimoy’s portrayal of Spock informed much of what would later be developed as the Vulcan culture. Nimoy went on to star in seven Star Trek movies, two of which he also directed, between 1979 and 2013.

For Nimoy, his Star Trek fame was both a blessing and a curse. He found it extremely difficult to get cast in movies because of his close association with the role of Spock, and outside of his Star Trek work, his only major feature film role is that of a psychiatrist in the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978). He was, however, cast in a principle role in the TV series Mission: Impossible from 1969 to 1971, and went on to do a host of well-regarded TV movies, some of which he directed. He thrived on the stage, winning acclaim for a string of lauded appearances in the 70s and 80s, and started an audiodrama company which brought several science fiction classics to radio and audiobook listeners. He had a brief, mostly humorous, career as a music artist, published several poetry books and was an accomplished photographer. He narrated several TV shows and made numerous cameos and guest appearances. Nimoy passed away in 2015, and following his death, an asteroid was named after him.

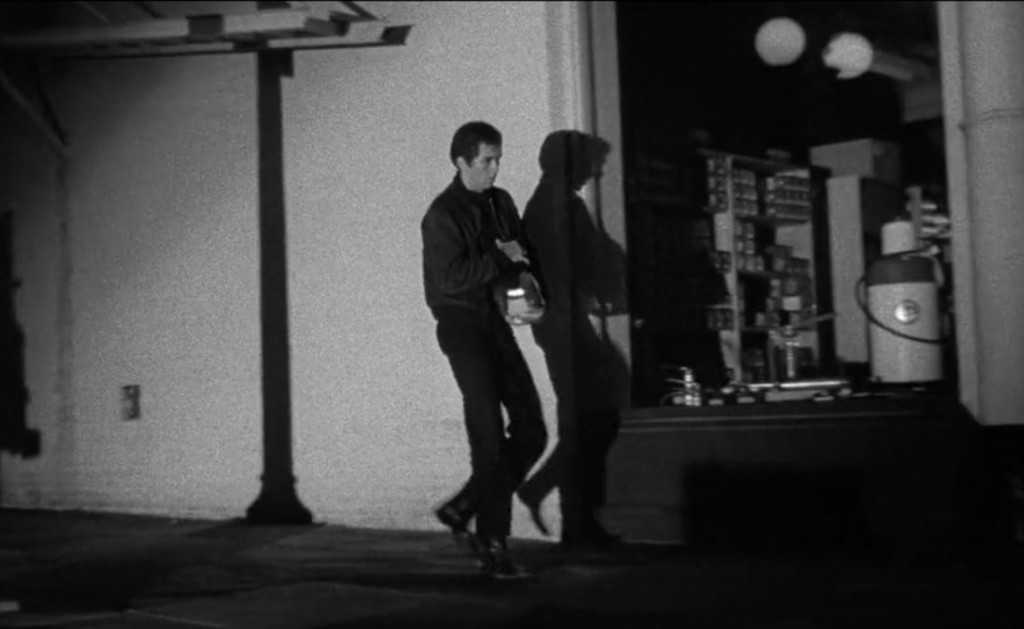

Another interesting name is Hampton Fancher, who in The Brain Eaters (1958) plays a minor role as a “zombie” who carries around a glowing orb which contains a parasite. This was Fancher’s first film role – according to him, someone (probably Ed Nelson or Bruno VeSota) spotted him on the street and asked if he wanted to be in a movie.

Today Fancher is best known as the co-writer of Blade Runner (1982) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017), but in 1958, at the age of 20, he was still working as a flamenco dancer, a career that made him drop out of school at the age of 14 and go to Spain. A trouble-maker with learning disabilities, school was not for Fancher, who instead had an adventurous youth and, paradoxically, became a voracious reader, especially of Philip K. Dick, William Burroughs and Charles Bukowski. Dark and handsome, he was a ladies’ man and a party man, and his experience on The Brain Eaters set him on a career path to become an actor. According to Fancher himself, he was “a bad actor in bad TV shows”. Of his around half dozen movie roles, the most prominent are probably two supporting roles in films by Delmer Daves, starring Troy Donahue: Parrish (1961) and Rome Adventure (1962), which was filmed in Rome. Fancher had a starring role in Albert Zugsmith’s 1966 sex comedy The Incredible Sex Revolution, and in 1969 he was cast as Romeo in a German mini-series retelling Romeo and Juliet in modern times, with Romeo as a taxi driver and Julia as a shop clerk: Romeo und Julia ’70. The reason for this was probably his involvement in the West German movie How Did a Nice Girl Like You Get Into This Business? (1970). The film was centered around Playboy bunny Barbi Benton, and was shot in Rome. Fancher played one of the love interests of Benton.

By 1978, Hampton Fancher decided to leave acting behind and focus on his ambitions of becoming a screenwriter. Or, more specifically, try to get his adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? off the ground. He fought relentessly to get Dick to sell the movie rights, and finally succeeded, after which he and producer Alan Ladd had significant trouble finding a studio willing to make the movie. When Warner Brothers were on board, they signed Ridley Scott, hot off his success with Alien (1979) as director. Scott really liked Fancher’s script, but wanted significant changes to present more of the world in which the film took place, and more action. Fancher, who was more interested in the inner worlds of the characters, was bull-headed and prone to emotional outbursts and brooding, and refused to cooperate, so David Goyer was brought in to rewrite the script. Fancher clashed with Ladd and Scott, and at one point demanded his credit was removed from the film, and later demanded it be reinstated. Finally it came down to Goyer refusing to accept credit unless Fancher also received credit. After this, Fancher reconciled with Goyer and they became good friends.

Blade Runner famously flopped upon release and did little to further Fancher’s career as a screenwriter. Fancher also wasn’t interested in doing commercial Hollywood movies, but instead fought over the years for getting his more intellectual and artsy scripts produced, with little success. In 1989 he did manage to get his script The Mighty Quinn produced, a breezy, unusual crime caper starring an up-and-coming Denzel Washington. The film was lauded by critics but again, didn’t help Fancher much in the business. His third, and second-to-last produced screenplay was The Minus Man (1999), a quirky serial killer movie starring Owen Wilson and Sheryl Crow, which was nominated for the Grand Prize at both Sundance and the Montreal Film Festival. Fancher also directed the movie, his sole directorial credit.

After this, Fancher had little luck getting his projects into production, until he was contacted by the producers of Blade Runner 2049 about writing the script for highly anticipated sequel. Once again, his script was re-written, this time by Michael Green, but now with the approval of Fancher. The script was nominated for an Oscar and a Hugo Award.

In 2017, Wes Anderson produced the documentary Escapes, which told the story of the life and career of Hampton Fancher.

EDIT: Joanna Lee of course created the Flintstones character The Great Gazoo, and not Magoo.

Janne Wass

The Brain Eaters. 1958, USA. Directed by Bruno VeSota. Written by Gordon Urquhart & Bruno VeSota. Based on Robert Heinlein’s novel The Puppet Masters. Starring: Ed Nelson, Alan Jay Factor, Cornelius Keefe, Joanna Lee, Jody Fair, David Hughes, Robert Ball, Phil Posner, Orville Sherman, Leonard Nimoy, Hampton Fancher. Music: Tom Johnson. Cinematography: Lawrence Raimond. Editing: Carlo Lodato. Art direction: Burt Shonberg. Makeup: Alan Trumble. Produced by Ed Nelson & Roger Corman for Corinthian Productions & American International Pictures.

Leave a comment