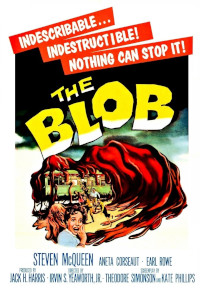

27-year-old teenager Steve McQueen must save small-town Americana when a flesh-eating blob arrives from outer space. This quaintly naive little film has become iconic, despite its clunky, slow-moving script and its impoverished production. 5/10

The Blob. 1958, USA. Directed by Irvin Yeaworth Jr. Written by Irvine Millgate, Thedore Simonson, Kay Linaker. Starring: Steve McQueen, Aneta Corsaut, Earl Rowe, Olin Howland. Produced by Jack Harris. IMDb: 6.3/10. Letterboxd: 3.1/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 6.3/10. Metacritic: 58/100

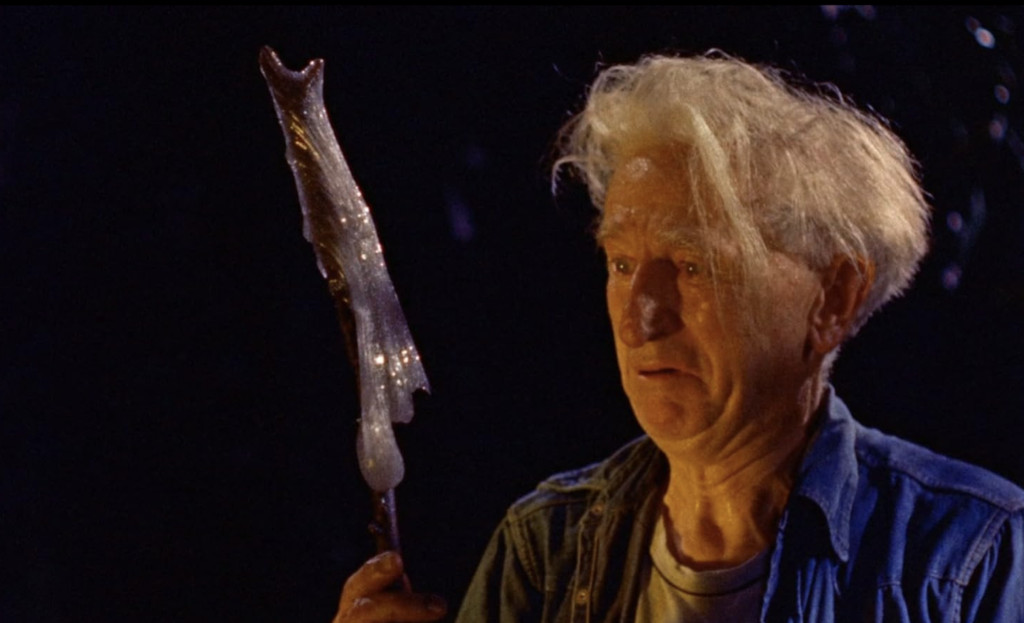

While riding his convertible down a Pennsylvania smalltown road at night, young lover Steve and Jane (Steve McQueen & Aneta Corsaut) nearly run over an Old Man (Olin Howland), who has gone and stuck himself in a gelatinous blob contained in a meteor. The blob his now devouring his hand, and he can’t get it off. Steve and Jane take him to the local doctor (Stephen Chase), who fails in getting it off Old Man’s hand. Instead, the blob devours first the nurse and then the doctor himself. Steve and Jane rush to the sheriff (Earl Rowe), but down at the sheriff’s office, none of the adults take the rambling teens seriously. It’s now up to Steve, Jane and their teenage friends to save the town, and perhaps the world.

Yes, it’s the timeless classic The Blob, a monument to 50s small-town Americana and to the 50s monster movie. While filmed in Technicolor and distributed by Paramount, Irvin Yeaworth’s 1958 Magnum Opus is still the epitomy of the low-budget exploitation science fiction movie.

After the attack on the doctor and the nurse, we pretty much lose sight of the blob for much of the movie. Instead, we follow Steve, Jane and their teenage friends as they try to convince their parents, law enforcement and the townsfolk that they’re not pulling a prank, culminating in a classic scene where all the teens show up at the local store where the blob is currently located, honking their car horns as a Klaxon call in the middle of the night to wake up the adults.

This is followed by another iconic scene, as the blob enters a late night movie show, devours the projectionist and starts squeezing itself out of the projection booth, sending the teenage audience careening out of the theatre. Likewise engrained in our collective memory is the finale, when Steve and Jane get trapped by a now gigantic blob (that has reportedly devoured over 50 people) in a diner.

Background & Analysis

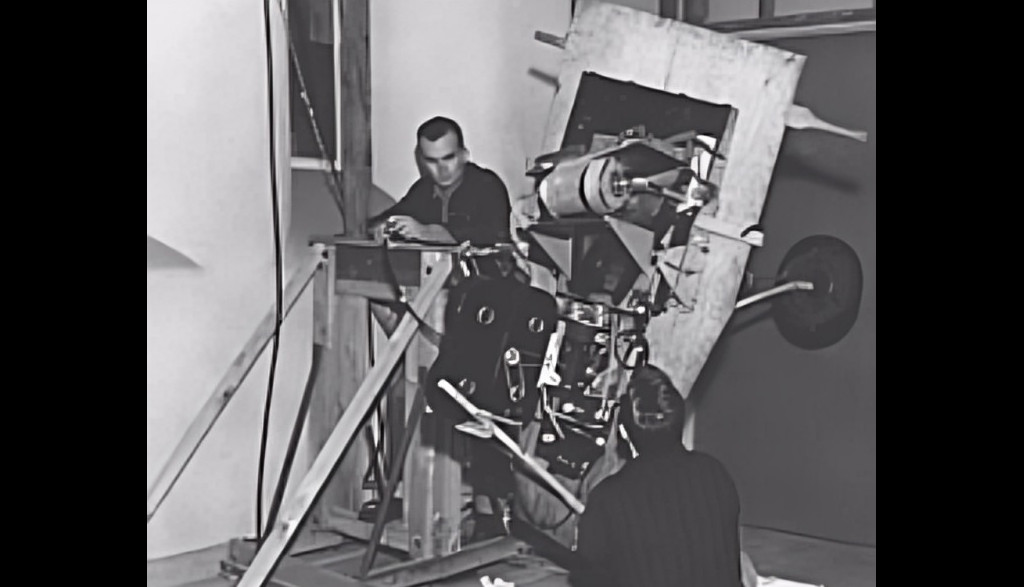

The Blob (1958) was not filmed in Hollywood, but rather in and around Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. If you’ve seen Tim Burton’s film Ed Wood, about how Wood tried to get his science fiction movies produced by getting a religious group to invest in it, in order to raise money for their religious films, then you’ll get an idea for the production of The Blob. Only in this case, it actually worked.

The mastermind behind The Blob was producer Jack H. Harris, a native of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who had been working in movie distribution in both New York and Los Angeles. Tired, as Tom Weaver puts it, of the “minor black-and-white pictures foisted upon him”, he decided to produce his own movie, and contacted the religious movie company Valley Forge Film Studios, a studio that was specialised in producing religious short films, ran by an association called Good News Productions. He convinced them to produce a commercial feature film in order to raise money for their cause, and they were enthusiastic. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Harris said that the original story came from Irvine Millgate, who was a visual aid producer at the Boyscouts of America. Millgate knew that Harris wanted to produce a movie, and came up with the concept of the blob – a mineral monster that devoured flesh and could not be destroyed by any means known to man. Harris liked the idea and presented it to the ministers at Vally Forge Film Studios. One of them, Theodore Simonson (a minister), set about to write the script, and it was further polished by professional screenwriter Kay Linaker (billed as Kate Phillips). As director was chosen the man at the heart of Good News Productions, essentially the director of Valley Forge Studios, who had also directed a cautionary movie about a young man who seeks the adventure of the big city and gets caught up in a sinful life, later released with added footage as The Flaming Teen Age (1956), Irvin “Shorty” Yeaworth, Jr.

According to Harris, he was adamant that the film was to be made to the standards of a Hollywood movie, despite being filmed in Pennsylvania, and despite the studio being made up of two old barns and a former military hospital converted into an editing studio. He tells Weaver that the crew was largely made up of seasoned pros from Valley Forge Films. None of them had any experience with making a feature film but, “at least they had the technichal facility to understand what a camera was, and to know enough not to split somebody’s skull with a microphone boom”. Harris had enough contacts to Hollywood to provide a few professional movie actors for the central roles, and the rest of the cast was made up of people associated with Valley Forge Films – some of them accomplished actors from the screen, radio and local TV, but few with any actual movie experience. Depending on the source, the film had a budget of either $110,000 or $230,000. The latter comes from Harris, and it would seem more approriate for a film with a shooting schedule of 31 days and a nine-month post-production period. Anyway you look at it, it’s a low-budget film. The first number is about the same as the average AIP budget, and the second equals out to the budget for the “B plus” films made by Robert Lippert’s Regal Films or the ones produced by United Artists at the time. The movie was filmed at Valley Forge Film’s small studio in Yellow Springs, and in and around Phoenixville, using existing streets and locations, such as the cinema and the diner, both existing and famous today.

Steve McQueen was not a known name at the time, as highlighted by the New York Times review, which notes that “there is becomingly not a single familiar face in the cast”. He had primarily appeared on television, and this was his first substantial movie role. Playing the female lead, Aneta Corsaut had only a few TV credits under her belt. Strengthening the cast from Hollywood was also veteran Olin Howland as the old man who first gets attacked by the blob, Stephen Chase as the local doctor and John Benson as one of the police officers. Earl Rowe, who plays the sympathetic chief of police had studied drama in Pennsylvania, and appeared regularly on radio and on stage in New York. Several of the other roles were also filled out with stage and local TV actors primarily active in New York, as well as a good amount of local talent both in bit-parts and as extras. Among the crew, the only Hollywood addition seems to have been composer Ralph Carmichael.

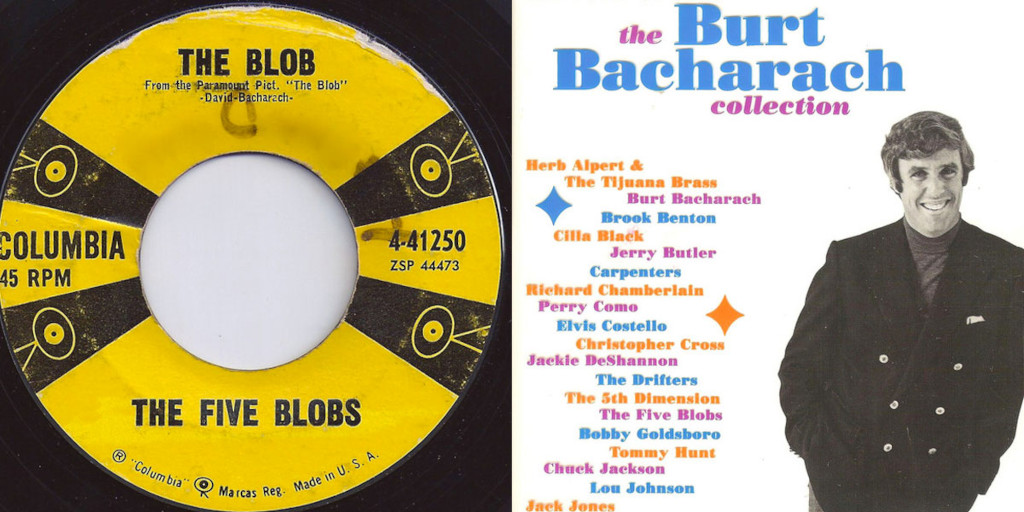

Another addition, albeit last-minute, was Burt Bacharach, an up-and-coming pop music composer, who was enlisted to write a song for the opening credits to replace the original credit theme by Carmichael. Harris decided that he wanted an up-tempo toungue-in-cheek pop song in the beginning to put the audience in the mood for camp, rather than for a traditional horror movie. Bacharach wrote the music, and the famous seven lines of lyrics were written by Mack David, brother of Bacharach’s frequent collaborator Hal David: “Beware of The Blob, it creeps / And leaps and glides and slides / Across the floor / Right through the door / And all around the wall / A splotch, a blotch / Beware of the Blob”. “The Blob” was recorded by a group of Los Angeles studio musicians who called themselves The Five Blobs. The band was led by Bernie Knee, who overdubbed his own vocals on the recording, making it sound like the song has multiple singers doing harmonies. The song became a minor hit and also helped the success of the movie.

Plot-wise, The Blob is basically a retread of AIP’s campy SF spoof Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957, review). I don’t know why a Methodist minister would have seen Invasion of the Saucer Men, but the similarities feel too many for them to be a coincidence. On the other hand, the teenage tropes were so prevalent by this time, it could just be a case of cultural osmosis. In both films teenagers making out in their cars discover an alien invasion in the woods, and try to warn the authorities and their parents, but because they are teenagers, no-one takes them seriously. So they decide to take matters into their own hands, and in the end, all the teenagers of the small town gather in their cars in a last decisive stand.

In a way, The Blob is a classic 50s teen movie, but on the other hand it is a kind of reversal of the prevalent trend, feeling more like an over-long episode of Happy Days than an actual 50s teensploitation film. Inspired by the successes of films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Blackboard Jungle (1956), most teensploitation films portrayed teens as morally decayed, delinquent, confused, unhappy and att odds with their elders and society. These films often focused on crime, violence, drinking, underage sex and drug abuse. By comparison, the teens in The Blob are the most wholesome bunch you’ll ever meet. There’s no smoking, no drinking, and the closest anyone comes to a sexual act is holding hands at the movie theatre. The biggest prank they pull is moving a friend’s car down the block, and their dragracing stunt consists of reversing past a red light. The two leads seem perfectly well adjusted and in good standing with their parents. Even the local sheriff likes the kids.

That the film features little immoral behaviour may partly be explained by its religious backers. In a way, it feels as if Simonson and Yeaworth have set out to redeem the young generation, showing that they really aren’t all that bad as Hollywood wants to portray them. Here, like in Invasion of the Saucer Men, the teens turn out to be the ones that put themselves on the line to save their community.

As author & critic Eric Magill points out in his Youtube restrospective on the channel The Unapologetic Geek, assigning themes to The Blob is probably overstepping anything that the creators of the film had in mind, as this was not an attempt at creating anything particularly meaningful, but rather to make a fun, commercially successful piece of camp that would allow the good folk at Valley Forge Film Studios to continue spreading the word. However, it is hard not to see in the film an exploration of generational rift between the so-called Interbellum generation and the Silent generation, i.a. the generation that served in WWII, and their kids. The former is most vocally represented on the film by Officer Ritchie, who complains that he did not fight for his country and get wounded in the war in order to be made the laughing stock for a bunch of ungrateful kids. However, this theme merely serves as a backdrop to the movie, and never delves deeper into the matter. The film ends on a hopeful note, however, with the kids and their elders joining forces in the battle against the blob.

As Chuck Bowen points out in Slant magazine, The Blob is also “one of the most pointedly reactionary” science fiction movies of the 50s: “Unlike a number of conflicted, unsettling alien-invasion films of the era, such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Invaders from Mars, The Blob ultimately offers a reassuring fantasy. The adults of the film eventually discover that the kids are all right (i.e. obedient), and that the source of their society’s disruption can be conveniently whisked away to the Arctic for permanent deep-freezing. It’s telling that the alien could almost be removed from The Blob entirely without altering much of the film, as this is a youth hang-out movie first and foremost, only with all potentials for chaos and anarchy comfortably scrubbed away.”

There is a temptation to view every 50s invasion movie through the cold war lens, since a lot of the SF pictures from the first half of the decade commented, in one way or another, the geopolitical situation – be it as warnings against the dangers of Communism and the Soviet Union, or as a critique of the “reds under our beds” mentality – or indeed offered pacifist points of view in a time of hightened political and military tensions. Viewed through this lens, one could add the blob to the long list of socialist monsters upsetting small-town Americana – but this would be to stretch the metaphor to lengths that the film simply does not support. There is no notion in The Blob that it is to be taken as a geopolitical allusion in any form.

The idea of the menace that keeps feeding and growing, threatening to take over the world, was already a familiar trope. One could argue that it originated in Arch Oboler’s and Wyllis Cooper’s groundbreaking horror/SF radio show Lights Out! in 1937, in abn episode about an experiment which makes a chicken heart grow out of control. A very similar idea was used in Ivan Tors‘ movie The Magnetic Monster (1953, review). However, the the true father of the blob was Hammer’s unofficial Quatermass sequel X the Unknown (1956, review), which featured an ever-growing mass of goo that fed on radiactivity. According to one version, story originator Irvine Millgate came up with the idea for the film after reading a newspaper story (from 1950) about police officers in South Philadelphia encountering a gelatinous blob commonly known as “star jelly”, a colloquial name for different types of gelatinous “blobs” that appear seemingly out of nowhere and quickly disappear – which have sometimes been speculated to have extraterrestrial origins (scientists believe stories about star jelly are caused by either heaps of half-digested spawn jelly that have been vomited by predators, or different types of algea and fungi). However, this claim may well be a later addition by Philadelphian producer Jack Harris.

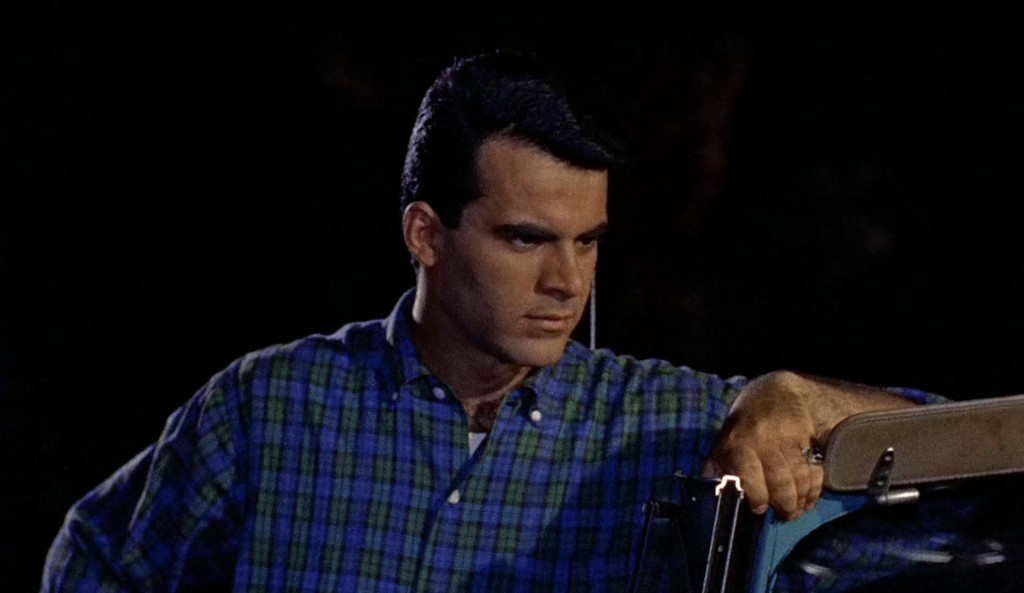

When it came to casting, Jack Harris had originaly considered an up-and-coming stage and TV actor called Anthony Franciosa for the lead. At the time, Franciosa had been nominated for a Tony Award, and won other awards, for his work in Michael Gazzo’s play A Hatful of Rain on Broadway. However, when Harris went to see the play in late 1956, Franciosa’s co-star Ben Gazzara was sick, and his part was played by his understudy, an unknown actor by the name of Steve McQueen. Harris was so struck with McQueen’s energy and charisma that he knew that he had found his leading man. There was only one problem: the people at Valley Forge already knew McQueen, and wanted absolutely nothing to do with him. In early 1956, McQueen’s then-girlfriend, later wife, Neile Adams had taken part in a religious short film directed by none other than Irvin Yeaworth, Jr. In his later career, McQueen had a reputation of being notoriously difficult to work with, and, frankly, an asshole, and that behaviour had already taken root. Yeaworth and the rest of the crew absolutely hated McQueen’s guts. However, after seeing McQueen again in a TV production, Harris was sure he had his star: “The long and the short of it was that he played Steve McQueen in everything […] That indicated star quality to me”, he sais in his interview with Tom Weaver. Harris was able to convince the Valley Forge people and signed McQueen not only for one film, but for a three-picture contract. However, after the ordeal of dealing with him for the duration of the shooting, even Harris was fed up, and released McQueen from his contract. In hindsight, says Harris, had he known what a major star McQueen would become, he would never have let him go. McQueen’s co-star Aneta Corsaut wasn’t cast until the second day of shooting.

Of course, 27-year-old McQueen doesn’t fool anybody that he’s a teenager, but he’s got a twitchy energy that at least lets us keep some suspension of dispbelief. McQueen was the oldest teenager in the movie, but it’s not like the rest of the juvenile non-delinquents were exactly spring chickens, either. Aneta Corsaut was 24 during filming, Robert Fields, the leader of the teen gang, was 23 with a heavy stubble and another teenager, Pamela Curran, was also 27. The youngest teenager I have found in the bunch was 20-year-old Molly Ann Bourne. Of course, this was another trope of the teensploitation movie: there were hardly ever any actual teenages in them. James Dean was 24 when he did Rebel Without a Cause (and it showed) and almost all “teens” in Blackboard Jungle were between 21 and 25 years of age.

Revisiting these 50s teensploitation movies today feels a bit like seeing a stage play, rather than watching a movie. At the theatre, there’s a contract between the audience and the player allowing stage performances to stretch, subvert and shatter reality with things like age, race and gender blind casting. In a setting where plywood walls or even just a black box can represent anything from a Medieval castle to bustling New York street, where so much of what we exprience relies on our own imagination filling in the blanks, an 82-year-old Ian McKellen can play (teenager) Hamlet, and an none-white cast can put on a performance of Hamilton. Theatre is ultimately about ideas, and the nature of the live stage play means that we don’t expect reality. Movies, on the other hand, are (mostly) created to resemble reality as closely as possible. Sets, props, lighting, sound design and effects are designed to give us an illusion of (heightened) reality, and when any of these aspects fail to convince us, the illusion is shattered, taking us emotionally out of the intended state of mind. 50s teensploitation movies often have this effect, partly because it is painfully obvious that many of the actors are at least ten years too old to play teenagers. Of course, this is not the only thing shattering illusions in old science fiction B-movies, but it is one of those things that doesn’t need a large budget to correct, which is perhaps why it often feels grating, even in lesser films.

The Blob is partly able to overcome the problem by occasionally emphasizing the camp value of the film, beginning with the title song. However, the movie would have benefited from turning up the camp factor further. As it stands, it often comes too close to straight and sincere scripting, which threatens to confuse the viewer – are we supposed to take this seriously or not? Our characters are a bit too heart-warming and wholesome, all situations work out a little too neatly, and conflicts are a bit too insignificant and work themselves out a little bit too neatly for this to work either as camp or as serious drama. The film balances oddly between different genres and audience groups. It’s not quite dark enough to qualify as a horror film, despite the fact that a lot of effort has gone into the creation of the titular monster, and it does follow a classic horror film formula. It’s not funny enough (or even attempting to be) to be viewed as a comedy, satire or spoof, despite leaning into its camp. It’s too wholesome to cut it as a teensploitation movie, despite taking its formula directly from the teensploitation genre. And it’s just a little bit too scary and deals with a little bit too grown-up themes to have been considered a family movie back in the 50s.

The script is thin and the dialogue often clunky. The romance is tepid and no sparks ever fly between McQueen and Corsaut. The generational conflict is there as a backdrop to the story, but the teens are too sanitized and the adults too much cardboard cutouts for the film to even begin discussing the theme. On the positive side, the script is occasionally is able to conjure up some tension, and the movie comes into its own during the finale when the blob attacks first the movie theatre and then traps the protagonists in the diner. However, it gets sidetracked once too often, and the leisurly pace at which it proceeds does take away from the titular menace.

Steve McQueen aside, the real star of the film is the titular goop. The movie’s working title was “The Molten Meteor”, but then someone overheard one of the crew calling the menace of the film “the glob”, and thought that would make a good title. However, they also (erranously) thought that “The Glob” was copyrighted and decided to instead call the film The Blob.

The concept itself is not particularly novel. On one hand it’s a classic from fairy tales of old: a monster that eats people. Secondly, it’s an “alien” organism that threatens to grow and spread and ultimately take over the world. This kind of threat was already a staple in SF in the late 50s, and ultimately has its roots mythical eschatology, but came into its modern form during the early 19th century with novels such as Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville’s Le dernier homme and Mary Shelley’s The Last Man. In the former, the “blob” was represented by infertility, in the second by a plague. As stated, the idea has since been represented by Arch Oboler’s chicken heart, Ivan Thors’ radioactive monstrosity, Nigel Kneale’s alien spores in The Quatermass Experiment (1953, review) and Hammer’s radioactive goo in X the Unkown.

However, what was novel in The Blob was the visuals. This was the first time a menace like this was represented in colour, and the gelatinous blob was something movie-goers had never seen before. From the moment the goo attaches itself to the old man’s hand, the blob is something mysterious, ominous, unknowable, and when it first rolls out in its finished form as a cherry red ball of ick in the doctor’s reception, it’s a thing to behold. It’s just a small glimpse in a window, but the scene where it devours the doctor’s head is classic shock cinema, not to speak of the finale, when the thing oozes into the movie theatre and later presses its now giant form out through the cinema gates. These scenes are the most effective and classic in the movie.

The blob comes courtesy of special effects technicians Bart Sloan and Evan Baldwin, and was made out of silicone with added food dye. To make the blob move on its own, the special effects team devised a simple yet effective technique. The blob, along with miniature sets and cutout photographs, were place on a tilting table, to which the camera was also fixed. By tilting the table, the blob was made to roll, move and undulate with the help of gravity. It didn’t allow for a particularly wide range of movement, but quite enough to achieve the desired effect. However, it is also the effects that most clearly show the limits of the budget and film crew. In the final scene, where the blob is encasing the diner, budget became an obstacle, and the crew simply had the blob roll over a photograph of the building. In its final form, encasing the diner, a simple painting with some additional cel animation was used. It’s a pretty bad effect, even by the standards of the time.

The direction by Irvin Yeaworth, Jr. also leaves much to be desired. Many scenes are shot only from one single direction, and and many shots are cropped tight to hide the lack of sets. In several instances, the actors are shot against black backdrops, making them feel oddly detached from reality, almost as if they were acting in a black box theatre. In the live action footage, most scenes are shot flatly and uninterestingly. One memorable exception is the scene in which the teenagers are fleeing the theatre, and the camera dynamically catches the kids from a frog perspective, in a shot that looks like hand held camera. However, this was reportedly, an accident, as the cameraman was knocked over by the running mob. This scene also showcases the way in which local townspeople were involved in filming. If you look at the faces of the running crowd, it’s not terror on their lips, instead most of them look happy and excited, laughing from ear to ear as they are allowed to take part in a movie shoot, dashing out from the cinema as they pretend to be escaping a monster. The film looks as good as it looks thanks to its special effects photography, and not thanks to the work done by Yeaworth. Of course, the colour and Paramount’s semi-wide 1.66:1 ratio does also lend the picture an air of class that it frankly doesn’t deserve.

The Blob is a film that, in a way, is able to transcend its own clunkiness. Yes, the script is derivative, slow-moving, quite daft and thin. The production values are impoverished and the cinematography and direction often sub-par even for a low-budget film. The acting is wildly uneven and the dialogue occasionally cringe-worthy. But in its oddly upbeat naivety, the film has an unmistakable charm. The movie really wants us to like the characters. The film has no villains, and even the naysayers are ultimately kind-hearted and good people. For all its death and horror, it is a heart-warming feelgood movie about people setting aside their differences and coming together to save their town. I suppose in a way it portrays 50s small-town America the way we would like to remember it: as a place where you know your neighbours and are friend with the sheriff, and where the worst things that happen are some kids reversing through a red light. There’s the classic all-American diner, the local movie theatre and the mom-and-pop general store. It’s a time capsule that shows things the way we would like them to have been. And the blob itself is just so iconic it has become one of those movie tropes that transcend the movies they originated in. Like Godzilla and King Kong, that cherry-coloured lump of gelatin is recognised by generations of people, regardless of whether they have seen the film or not. It is now almost a week since I watched the movie and I catch myself remembering it much more fondly than I felt about it when I watched it, which is a powerful thing. But I try not to let The Blob’s devious wholesomeness cloud my judgement. The fact is that despite its deceptive allure, it is not a particularly good movie once you actually sit down to watch it.

Reception & Legacy

The Blob Premiered in September, 1958, in many places on a double bill with I Married a Monster from Outer Space (review). It was a major success, and raked in $4 millions at the box office, making it the biggest science fiction movie of the second half of the 50s, rivalled in box office earnings only by Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), which came up just short of the $4 million dollar mark.

However, reviews were mostly negative, even contemptuous, which film historian and critic Bill Warren puts down to general feeling about science fiction horror movies at the time. Cinemas were being flooded with low-budget SF and monster movies, as studios competed in milking the last out of the diminishing science fiction trend of the 50s. On the other hand, among many major outlets, horror movies of the 50s kind were still a novelty (the big newspapers and magazines didn’t usually bother with low-budget genre movies), and regular reviewers were a bit late to the horror-bashing party. In Saturday Review, for instance, the critic didn’t so much review the film as he did the genre, bemoaning its corruption of the youth. Cue magazine went as far as recommending a boycott of the movie. Howard Thompson at The New York Times gave a more balanced review, but was not a fan of the film, either. He did give some credit to the colour photography and the way in which the small town was photographed, and praised the scene in which the blob attacks the movie theatre. However, he called the film “wooden”, complained about bad acting, worse dialogue and “phony” special effects, and noted that “unfortunately, this picture talks itself to death, even with the blob nibbling away at everyone in sight”.

Harrison’s Reports suggested that the film should do decent box office thanks to the colour photography, but didn’t think much of the film itself. According to the magazine, it was a routine movie of its kind, and too stretched-out, at that. Variety also predicted good business, but was otherwise indifferent to the movie: “Neither the acting nor the direction […] is particularly creditable. Mcqueen […] makes with the old college try while Miss Corseaut also struggles valiantly as his girlfriend.” Critic Gilb did, however, give the special effects and cinematography good ratings.

British Monthly Film Bulletin gave the movie its middle (II) rating: “Although [the earlier] special effects are splendidly contrived, the ‘blob’s’ eventual restaurant-absorbing feat goes far beyond conviction, and the film fails to maintain its early promise as an eerie exerceise in Science Fiction hokum.”

In his book Keep Watching the Skies!, Bill Warren writes: “Overall, The Blob is not a classic, but it is respectable and intelligent, certainly worthy of more praise than it has generally received”. In The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, Phil Hardy gives the film a fair review: “Sloane’s effects are authentic […] but both direction and script are lackustre. Nonetheless, the blob itself, and the idea of teenagers saving (rather than destroying) small-town America results in a strangely appealing, if camp, movie.”

As of writing, the film has a 6.3/10 audience rating on IMDb, based on over 30,000 votes, making it by a long shot the most popular film I have reviewed in ages. It has a 3.1/5 rating on Letterboxd, based on over 47,000 votes. Critic aggregate Rotten Tomatoes gives it a 6.3/10 rating. This film even has a Metacritic score, a rarity in these circumstances. Metacritic gives it a fair 58/100 score.

In Slant magazine, Chuck Bowen gives the movie a 3.5/5 rating. He writes: “The film’s tone suits its monster; it’s creepy in a nonsense fashion that’s probably mostly a happy accident. The Blob is one of those horror films that benefits from surreal dissonances that have arisen from a simultaneous lack of resources and technical inconsistency. […] These technically incorrect shots are often the eeriest in the film, and they also bolster the theme, commonplace of alien-invasion films mostly made during the second Red Scare, of outsiders attempting to convince authority figures of an insidious invader.”

The Observer (UK) called The Blob “clever, tongue-in-cheek and far more fun than the hi-tech remake”, and CNN described it as “a fun ride all the way through”.

DVD Savant Glenn Erickson says that “one of the best-remembered 50s movie monsters, The Blob has persisted in the public consciousness despite pedestrian direction and a pace that’s on the poky side. […] Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr’s sincere direction shapes characters as warm as those found in the TV family sitcoms of the day. […] unlike the teens of American-International’s Earth vs. The Spider (review) and Invasion of the Saucermen, they’re sarcasm- and irony-free.

One critic that isn’t taken in by the film’s charm is Richard Scheib at Moria, who gives it only 1.5/5 stars: “On the minus side, The Blob is more interesting as subtext than it ever is as drama. Director Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr has a major problem with pace – the mildly exciting blob scenes alternate with long periods of inaction where characters sit about and tediously talk.”

With its enormous success, The Blob became a cultural phenomenon, and even today is seen as the epitomy of the cheesy science fiction/teensploitation mashup of the late 50s. The movie allowed allowed Yeaworth and Harris to continue making monster movies for Valley Forge Studios, with 4D Man (1959) and Dinosaurus (1960). After Paramount’s rights to The Blob ran out in 1965, Jack Harris bought back the rights and re-released it several times with good commercial success. Harris made a sequel in 1972, Beware! The Blob, which was the sole directorial effort of actor Larry Hagman. The Blob (1988), with state-of-the-art effects, also produced by Harris, was directed by Chuck Russell, who at the time was best known for directing A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987) and went on to direct such blockbusters as The Mask (1994), Eraser (1996) and The Scorpion King (2002). A second remake of The Blob has been in the works since 2009, but it has languished in development hell. After Harris passed away in 2017, his widow Judith Parker Harris is the rights holder. As of 2024 the properties were with Warner Bros., with horror specialist David Bruckner attached as director and David Goyer and Keith Levine as producers.

The Blob has been referenced, homaged of ripped off in numerous other films, like Caltiki – the Immortal Monster (1959), Grease (1978), Killer Klowns from Outer Space (1988) and Monsters vs. Aliens (2009). The term “blob” has also entered computer science, referring to big, amorphous chunks of data.

Since the year 2000, the town where much of the original The Blob was filmed, Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, has hosted the annual horror movie festival Blobfest. The centrepiece of the festival is a showing of The Blob at the original Colonial Theatre, which features in the movie, and every year, the festival recreates the scene in which the teenagers run of from the cinema. Downington’s Diner has also been restored, although, oddly, it has no reference of The Blob on its website.

Cast & Crew

Philadelphia-born producer Jack Harris started working in showbiz at the tender age of six, as part of a vaudeville act, but soon got interested in the movie business. He worked his way up from theatre usher to publicity, and eventually into distribution, and opened his own office in New York. However, he was itching for production, and approached the ministers at Valley Forge Studios in 1956 about making a teensploitation science fiction horror movie about a gelatinous goo eating the inhabitants of a little town. The Blob (1958) was made on a small budget in a small town, but became a smash hit in theatres, earning a box office profit of $4 million.

Harris and Valley Forge Studios were not slow to capitalize on the film’s success, and produced two more films in a similar vein, 4D Man (1959) and Dinosaurus! (1960), however none of these had the same impact as The Blob, and Valley Forge Studios and Harris parted ways. The ministers at Valley Forge used the money they got from the horror films and continued to produce religious movies, but Harris stayed on with horror. In 1970 he produced the demon film Equinox, and then made a sequel, Beware! The Blob (1972), which continued where the previous film left off and moved the action to Los Angeles. In 1973 he produced the “missing link” apeman killer movie Schlock by a young John Landis, and in 1974 the sci-fi satire Dark Star, written by Alien (1979) writer Dan O’Bannon and directed by John Carpenter, as essentially a student film. He produced the interesting thriller The Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), with Faye Dunaway and Tommy Lee Jones. In 1986 he made the low-budget Fred Olen Ray movie Prison Ship, also known as Star Slammer: The Escape, and ended his career with a remake of the film it all began with: The Blob (1988).

Director Irvin Yeaworth Jr, born in 1926, was the driving force behind Valley Forge Studios, and directed numerous religious short films before being approached by Jack Harris in 1956 to make The Blob (1958) as a means to support the studio’s religious output. He struck up a working relationship with Harris and went on to direct and co-direct two more horror movies with him, 4D Man (1959) and Dinosaurus (1960), before returning to his religious movies.

Lead actor Steve McQueen, of course, needs little introduction. A struggling actor, he got his first movie role in 1952, and worked on in primarily bit-parts and movie guest spots until he got his big break in 1958 in the lead of The Blob. This would remain his only science fiction movie. With his piercing blue eyes and his inimitable charisma, McQueen became the King of Cool throughout the 60s and 70s, rising to become one of Hollywood’s biggest stars in films like The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Great Escape (1963), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), Bullitt (1968), Le Mans (1971), Papillon (1973) and The Towering Inferno (1974). Notoriously bull-headed and difficult to work with, McQueen nevertheless brought in money for the studios, leading Walter Mirisch, the producer of The Great Escape and The Thomas Crown Affair to describe him as “a pain in the ass, but he’s worth it”. In the mid-70s McQueen was diagnosed with incurable asbestos-related cancer. Despite seeking “alternative cures” in Mexico, he passed away in 1980.

Aneta Corsaut was a struggling TV and stage actress when she was singled out for the lead in The Blob, which would remain her best known film appearance. She appeared in minor roles in a handful of other movies, but did most of her career on stage and in TV. She gained some manner of fame in the recurring role of Helen Crump on the Andy Griffith Show between 1963 and 1968. She is quoted as having said: “I’m neither ugly enough to be a straight character actress nor pretty enough to be a glamor girl, so I have to be an actress. I generally wind up playing the “nice girl” or the young mother who has a baby or wants a baby.”

Olin Howland, who plays the old man who first encounters the blob was an in-demand character actor, often in westerns and crime dramas, from the twenties onward. He played the undertaker in the 1939 sci-fi horror film The Return of Doctor X (review), starring none other than Humphrey Bogart, and had a role in Them! (1954, review) as a drunk who has seen a giant ant.

Janne Wass

The Blob. 1958, USA. Directed by Irvin Yeaworth Jr. Written by Irvine Millgate, Thedore Simonson, Kay Linaker. Starring: Steve McQueen, Aneta Corsaut, Earl Rowe, Olin Howland, Stephen Chase, John Benson, George Karas, Lee Payton, Elbert Smith, Hugh Graham, Vincent Barbi. Music: Ralph Carmichael. Cinematography: Thomas Spalding. Editing: Alfred Hillmann. Art direction: Bill Jersey, Karl Karlson. Makeup: Vin Kehoe. Special effects: Bart Sloane, Evan Baldwin. Title theme: Burt Bacharach, Mack David, performed by The Five Blobs. Produced by Jack Harris for Tonylyn Productions, Valley Forge Films & Paramount.

Leave a comment