An Indian princess and her two romantic rivals investigate claims of prehistoric mammoths wreaking havoc on villages. A US/Indian co-production starring Marie Windsor & Cesar Romero, this 1952 B jungle/SF adventure is competent but dull, saved only by its Indian locations. 3/10

The Jungle. 1952, India/USA. Directed by William Berke. Written by Carroll Young, Orville Hampton. Starring: Marie Windsor, Rod Cameron, Cesar Romero, Ruby Meyers. Produced by William Berke & T.R. Sundaram. IMDb: 4.7/10. Letterboxd, Metacritic: N/A.

Returning from London, where her father, the maharaja of India, is being treated for illness, Princess Sita (Marie Windsor) is immediately beset by questions about what she is going to do about a strange outbreak of rampaging elephants destroying villages in the countryside.

The Jungle (1952) is one of India’s earliest science fiction films, although it might be better called a cryptozoology film, as it concerns the hunt for a pack of giant elephant/mammoth hybrids. Or even more correctly, it might be called a jungle adventure film. The movie was made as a co-production between Lippert Pictures and the Tamil movie studio Modern Theatres, and featured an American/Indian cast and crew.

Princess Sita is informed that her majordomo Rama Singh (Cesar Romero) has been trying to deal with the elephant problem through sending his (former) friend, American shikari, or big game hunter, Steve Bentley (Rod Cameron) out with a team of 10 hunters to track and kill the rampaging animals. Only Bentley returned, telling crazy tales about prehistoric monster mammoths scaring the elephant hordes into stampeding. Among the 10 hunters who didn’t return was Rama Singh’s brother. Singh now believes that Bentley has turned and saved himself and let his men be killed by elephants, and has concocted the mammoth story in order to hide his own cowardice.

But stampeding elephants are not Princess Sita’s only problem. The conservative Kali cult believes that the elephant stampedes are the god Kali’s revenge on India because of the maharaja’s progressive politics, and for allowing the country to be ruled by a woman in his absence – a woman, no less, that has vowed to modernise the country and bring democracy and equality for women. Therefore, cultists are now stirring up trouble and plotting to assasinate the princess.

Thus the board is ready and the pieces are set. We have a conflict between two former friends, one out to prove his courage and innocence and the other to bring justice to a traitor and liar, we have a modern princess out to show everyone that women can, while having to dodge dodgy assasins. Before them a dangerous and arduous trek through the Indian jungles in search of the proposed monster mammoths. And off we go…

The characters and plot are presented to us in the film’s first fifteen minutes, and after that the rest of the 75-minute movie concerns the jungle adventure. We follow the three protagonists and their very large retinue, including Prince Sita’s overprotective aunt Sumira (Ruby “Sulochana” Myers), and dozens of soldiers and porters, trek through the wilderness by foot, elephant and river boat, along the way encountering numerous dangerous animals: leopards, tigers, bears, snakes and a wild boar. These animals are usually content with fighting each other, and seldom threaten our heroes. At one point a group of travelling Tamil acrobats and jugglers visit their camp and perform their tricks, the main event being an acrobat spinning on his stomach like a propeller on top of a 20-foot pole. Travelling through the stunning landscape of the Tamil Nadu state in South India, the entourage also encounter Kali assasins who are out for the princess’ life – but each time she is saved by Bentley. Slowly, the previously hostile Sita starts warming up both to the rugged American and to his fantastic tales about prehistoric mammoths. This just adds insult to injury for Rama Singh, who is nurturing hopes of winning Sita’s hand in marriage – and before the film is over, the two confront each other in a knife fight, and Rama Singh learns the truth about his brother…

Finally, with ten minutes of film remaining, the party finally encounter the woolly mammoths, and fail to snuff them out with hand grenades. As a monkey accidentally deposits a live grenade in front of Princess Sita, Bentley covers it with his body, and with his sacrifice proves his courage. The grenade also sets off a rock slide which conveniently kills the mammoths.

Background & Analysis

I originally hadn’t intended to review The Jungle (1952), as its connection with science fiction is flimsy at best – the mammoths, which are speculated to be hybrids of prehistoric mammoths and modern elephants – kind-of-sort-of puts the film in the same prehistoric beast category as other lost world films that I have previously reviewed, but only just. But in researching the Tamil invisible man film Maya Manithan (1958, review), I realised that The Jungle was actually an American-Indian co-production, which gives it some interest as one of India’s first sci-fi(ish) films.

By 1952, T.R. Sundaram was one of the top movie producers in Tamil cinema, which dominated the movie business in South India. In the late 30s, he had founded Modern Theatres Ltd, the first studio in South India with all the modern facilities required to produce a movie from beginning to end, in the city of Salem – in fact one of the first studios in the entire country. Sundaram was head of the studio, procucer and also a director. From the beginning he was adamant that Modern Theatres’ output would be of the highest technical and artistic quality, and when he founded the studio, the first thing he did was hire two German cinematographers to work as mentors for the young Tamil crew. And in 1952 he had another brainwave: invite over a Hollywood production company to Tamil Nadu and co-produce a movie with Hollywood stars in India.

Jungle films were all the rage in Hollywood B-movie circles in the early 50s, with drive-in theatres filling up with Lex Barker’s Tarzan movies, his predecessor Johnny Weissmuller in the Jungle Jim series and former Boy actor Johnny Sheffield doing his own “teenage Tarzan” thing in the Bomba the Jungle Boy movies. However, most of these movies were filmed in botanical gardens, among potted plants in studio backlots or simply in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park. The cost of bringing film crews and stars to the jungles of Africa or Asia, not to speak of the difficulties with finding local crews, location scouting, permits, logistics, etc, etc, was almost completely out of the range of Hollywood B-movie producers. So when producer Robert Lippert was contacted by Sundaram, it must have seemed like an offer he couldn’t refuse: you bring the script, the director, the stars and a small crew, and we’ll do the rest. For Sundaram and Modern Theatres it was a chance to reach out to the American market and boost the film on the Indian market thanks to its Hollywood star power, but perhaps more importantly: it gave the studio the chance to observe and work with a Hollywood production crew and learn how the big guys in Hollywood did their thing. The contact between Sundaram and Lippert was probably consilidated by Ellis Dungan, an Irish-American director who had just returned to the US from a 25-year-long distinguished career in Indian cinema. Dungan is credited as associate producer on The Jungle.

Robert Lippert of Lippert Pictures knew just the right man for to direct and produce the movie: William Berke, a 52-year-old veteran and B-movie specialist who usually wrote, produced and directed his own movies, mostly westerns, crime dramas and jungle films, for studios like Republic, Columbia and Lippert Pictures. Lippert assigned him as producer and director, with Sundaram acting as co-producer on the part of Modern Theatres. As screenwriter, Berke called upon Carroll Young, who had started writing Tarzan movies for Sol Lesser in the 40s, and would go on to write around two dozen films, almost all of them jungle pictures. Berke and Young had collaborated on five Jungle Jim movies for Columbia. Prolific B-movie regular Orville Hampton is credited with additional dialogue.

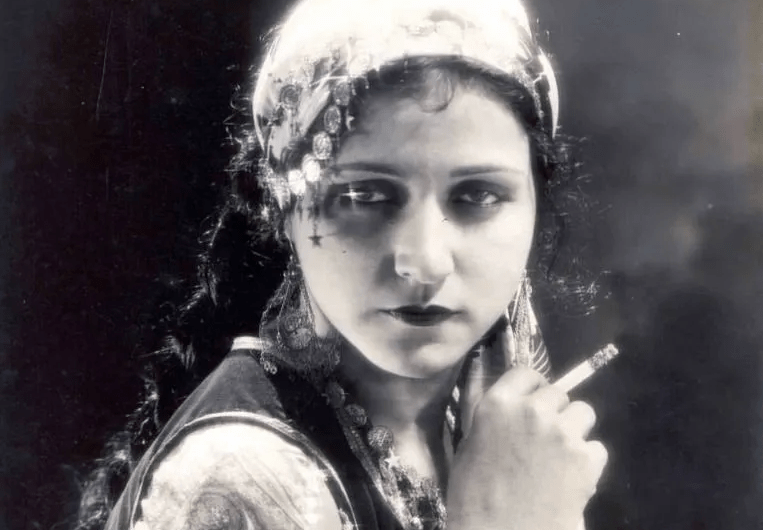

Although not the hottest A-list, Lippert provided decent star power for his Tamil counterparts. Rod Cameron might not have commanded quite the draw as he did as a poor man’s John Wayne in the 40s, but was still a name audiences remembered. As was Cesar Romero, the Latin Lover of so many movies past. The biggest draw might still have been Marie Windsor, who was riding high in 1952, having beguiled audiences with not one but two memorable turns as femme fatale in successful film noirs the same year: Richard Fleischer’s The Narrow Margin and Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper. Modern Theatres supplied their own “B” stars: Ruby “Sulochana” Myers was a decade past her prime, but was once the highest paid actress in all of India. M.N. Nambiar and David Abraham were both popular character actors.

According to some sources, two versions of the film was shot: One for the US market, which had a B-movie length of 73 minutes, and one for the Indian market, which was two and a half hours long. Alonger Indian cut of the film makes sense, as 2,5 to 3 hours was the standard length of a movie in India at the time. The Tamil title of the film was Kaadu, a direct translation of the English title. In an interview with Tom Weaver (thank you to Curt Fukuda for providing me with the article!) Marie Windsor says that Indian audiences were “very angry if in a picture you don’t have dancing, a love affair, some kind of war-type fighting, a mystery – all these things, they feel, have to be in a picture. And they have to have a long picture. And if it doesn’t all appear on the screen, they get mad and throw the benches at the screen!”

However, what those additional two hours were filled with is anyone’s guess. The US version is so devoid of any actual plot, that it is inconceivable that it could have been extended to the double without several additional subplots that simply aren’t present in the English-language version. The US version follows a traditional B jungle movie plot of the era: we have an introduction that presents the characters and tells us why they need to trek through the jungle, and then a conclusion an hour later. And the time in between is filled with footage of animals, endless walking scenes and some rather pointless soap opera-level personal drama.

The Jungle, however, has a clear edge over similar Hollywood-produced jungle films: India. There are some stunning shots of South India passing before our eyes, and the presence of numerous Indian actors and extras gives it a sense of realism that is sorely lacking in its Hollywood counterparts. The feeling of being present in India is enhanced by the soundtrack, which partly consists of Tamil folk songs – something you would not encounter in a film shot on a Hollywood backlot. We also have scenes of elephants destroying villages and a camp, and a scene where the lead actors are actually acting in front of a river filled with elephants in the wild, which again would have been unthinkable in a film made in the US.

As far as the plot goes, in the US version at least, there is not much to write home about. The idea that the maharaja’s daughter, current ruler of India, would have gone out on a jungle trek with practically no entourage other than her majordomo and her aunt is laughable. But even suspending our disbelief on this point, the plot is not particularly well conceived nor original. The hunt for the mammoths is simply a MacGuffin, an excuse for the characters to set out on a jungle adventure, and the only real drama sustaining the film for much of its running time is the rivalry between Steve Bentley and Rama Singh, which eventually also develops into a rivalry for the favour of Princess Sita. Marie Windsor and Cesar Romero do a good enough job in order for the drama to at least be bearable to watch, but it is difficult to root for the wooden plank that is Rod Cameron. Granted, he is slightly more lively here than in the British sci-fi clunker Escapement (1958, review), but “lively” is a relative term when it comes to Cameron.

What all this means is that most of The Jungle consists of the hunting party and their hundred porters and soldiers making their way through the – admittedly stunning – South Indian landscape – by car, by elephant, on foot and by boat. In between they have encounters with numerous animals – mostly shot elsewhere by the film’s B unit. Animal friends might want to look away from the numerous scenes in which deadly predators are pitted against each other in painful-looking fights. Windsor told Weaver she was so upset over a fight between a bear and a tiger that she considered suing the production company for animal cruelty. She filmed what was going on behind the scenes with her own camera so that she could show it to the authorities in the states: “But I guess they knew what I had in mind, because somebody stole my film”.

In between we have a number of badly scripted “dramatic” moments between the three main characters, tepid drama that never really goes anywhere. The finale with the mammoths is a major disappointment – elephants draped in shaggy carpets walk with a leisurly pace across the screen, with the main characters and dozens of extras doing their best to appear panic-stricken, firing guns and lobbing grenades at the “monsters”. The fact that hand grenades have no effect on mammoths is taking incredulity a step too far, considering that people in the days of old used to kill them with spears.

Other idiotic plot points also make their appearance. One is the fact that the hunting party deliberately make camp in the middle of an elephant path – something any Indian would know to be sheer lunacy. At another time Princess Sita’s aunt is mauled by a bear in an assassination attempt aimed at Bentley – because the two have switched tents. Of course the idea that a member of the royal family, whose members have been targeted by numerous assassination attempts – would be allowed to sleep alone in a tent without any guards is unthinkable.

These idiocies aside, we are also treated to a number of supporting characters that feel like they are supposed to play some crucial role in the plot, but which more or less disappear after they have been introduced. Aunt Sumira only gets a handful of lines. There’s also a careful introduction of a Kali fanatic, who makes no further appearance in the movie after being introduced. The script also makes sure to include the young boy Babu (Ramamkrishna) and his monkey on the journey, but Babu is also never seen again, and they seem to be included only so that the monkey can deliver the fatal hand grenade that Bentley throws himself on in the end. My guess is that we can see hints at the Indian version of the film in these characters. There were probably subplots involving these people (and their monkeys) filling up a decent amount of the remaining two hours of the Tamil version of the film, which, one would assume, were to a large extent filmed in the Tamil languge, without the main characters. My guess is that Babu might even have been something of a main character in the Indian version. All these subplots were probably erased from the US version of the movie, which might explain why it seems so devoid of any real drama for most of its running time. Instead, Berke and editor L. Balu chose to pad out the US running time with animal action. IMDb also states that some footage was shot at Universal’s studios and at Iverson Ranch, which suggests that additional footage of the lead actors was shot upon return to the US, which might be where Orville Hampton’s additional dialogue comes in.

Despite the stunning backdrops, the cinematography itself, by silent era veteran and location shooting specialist Clyde De Vinna is not particularly impressive. It is quite competent and has a few good action shots, but in general, T.R. Sundaram’s own work for the all-Tamil film Maya Manithan (1958, review), which I have recently reviewed, is much more fluid, inventive and versatile than the visuals in The Jungle. It would have been interesting to see what Sundaram would have been able to do with the film, had he gotten the chance to direct it. The film doesn’t seem to have any visual effects.

Interestingly, the movie is filmed in sepia. For those not familiar with the process, sepia is a warm yellowish tone, which as traditionally been achieved by chemically processing analog film. Its use began in still photography in the 19th century, originally because of practical reasons: the process makes photographs last longer, because sepia chemicals break down slower than ordinary black-and-white. But it was also a popular artistic choice, providing the photographs with a warmer tone. The colour range of sepia photographs were also popular in the silent movie era. Colour films have existed since the 19th century, either painstakingly hand painted, or, as in the case of many feature films, toned and tinted. Directors would often give their films a colour “wash” in order to create a specific mood, and would often use several different colour tints and tones in a single film: blue and green could indicate horror or suspense, pink romance and sepia tones could be used either to indicate security and familiarity, or to indicate antiquity or times gone by – such as a flashback. The sepia tones of movies generally weren’t achieved through the same chemical process as with still photographs, but rather through a paint wash.

The process of tinting and toning films continued into the era of sound pictures, even though few early talkies are available today as tinted versions – when copying films for example for television, it was often deemed to costly to tint and tone the new copies, so the films were simply copied onto normal black-and-white film. For example, the first prints of Dracula (1931) and the Marx Brothers comedy A Day at the Races (1937) were partly tinted. By the 50s, however, it was uncommon to release tinted movies – it was seen as an aesthetic of the past – only used in very specific situations for effects, more commonly in art than mainstream films. Thus, releasing The Jungle as a sepia movie was an interesting choice. One can imagine that director Berke thought that the sepia tone would emulate a feeling of both the exotic, hot landscape of India, and a sort of fairy-tale like atmosphere. The fact that it is tinted does set it apart from many of the similar jungle films of the era. It’s not in any way a detriment to the film, but I’m not sure it really adds much, either, other than a sense of slight originality.

A white elephant in the room is naturally the white-washing of the cast. Having Caucasian Marie Windsor play an Indian princess – in a movie shot in India, no less – seems both odd and inappropriate to a modern audience, as seems the casting of Cuban-born Cesar Romero as an Indian security officer. Of course, this was simply the way things were done back in the day, and the fact that the entire idea came from an Indian producer simply shows that this kind of reversed “colour blind casting” was generally accepted in the 50s. Despite both Windsor and Cameron being Caucasian, the budding romance of their characters would have been frowned upon both by US censors and large parts of the Indian society. In the US, interracial marriages were still taboo on the screen, and the notion of an Indian princess marrying an American would also have caused problems for the film in India. Note that the film contains no kiss between the two characters, other than a chaste kiss on the cheek. The problem was conveniently solved by having Bentley sacrifice himself in the end, leaving the road free for Princess Sita and Rama Sing to tie the knot.

That being said, both actors work surprisingly well in their roles. While none of them look particularly Indian, they somehow manage not to stick out like sore thumbs. Partly thanks for this should go to makeup artist G. Manickkam, who does a very convincing “Indian” makeup, in particular for Windsor. Windsor also plays the role with the restraint and bearing one would expect from a member of a royal family, helping to strengthen the illusion. All in all, both Windsor and Romero come across very much to their advantage in this film, contributing to making it watchable. The same can not be said for Rod Cameron, who has the gruffness of a John Wayne or Humphrey Bogart, but little of the nuance or range. The 5’9 tall Windsor joked in later years that she often found it challenging to work with many of her leading men, as movie convention stated that the leading men were supposed to tower over their female co-stars, rather than the other way round. It can hardly be a coincidence that Lippert and Berke chose two of the tallest leading men rattling around Hollywood’s B-movie scene for The Jungle – Cameron was 6’4 and Romero 6’3.

In her interview with Tom Weaver, Windsor says that the three lead actors stayed in India for seven months. According to her, there were no actual hotels in Salem where the Modern Theatres studio was located, so T.R. Sundaram had the studio buildings turned into accomodations for the US cast and crew. Much of the film, however, was spent on location, where the cast and crew slept in tents and so-called “government houses”. One of these houses was on the edge of an elephant trail, and one night everyone were awakened by a herd of elephants stomping past their windows. When camping, the Indian crew would build huge bonfires at night to keep tigers and elephants away. All in all, while the circumstances were apparently often primitive by Hollywood standards, Windsor and the US cast seem to have enjoyed their Indian adventure very much. According to Windsor, both Cameron and Romero were “quite good troupers about everything”. She particularly singles out Romero as “just so calm, coll and collected; he rolled with the punches in every way”.

Technically, The Jungle is a very competent B-movie with some stunning visuals. It has two very good actors in its central parts, which compensate for Rod Cameron’s shortcomings as a dramatic actor. But it only barely has a plot, and slogs from one exotic set piece to the next with just a half-baked personal drama stretching to keep it all together. The characters are all cardboard cutouts with just enough character arc in order to call the whole thing a drama. Nothing with any bearing on the central plot happens in the 50 minutes that make up the bulk of the picture. The fact that it is filmed in India is the only thing that makes this movie stand out against all the other jungle films flooding the market in the early 50s. Much better films were being made in India at the time, and it would be interesting to see what the Tamil version of the movie looked like – presumably partly filmed by one of the Indian assistant directors. US audiences in the 50s would have been wowed by the location footage, but for a modern viewer this film is mainly interesting as a curio.

Reception & Legacy

The Jungle premiered in the US in August, 1952, and had a wide international release over the following years. I have not found any release information on the supposed Indian version of the movie, as I have found no information on it, period. On a budget of around $125,000, it surely made back its budget.

Trade magazines generally noted that while the film didn’t score highly as a drama, the exotic locations and animals, in combination with a bankable trio of marquee names, would be enough for movie houses to make a profit on the film. Independent Film Journal wrote: “with the beautiful camera craftsmanship of Clyde De Vinna in evidence as well as eye-catching natural scenery and some good wild animal sequences, it is apparent that had the script been up to the standard of these assets, this film could top any bill. As it stands, Rod Cameron, Cesar Romero and Marie Windsor, despite their interesting surroundings, have a constant battle with static dialogue and a plot that leaves more to be desired.”

Brog in Variety echoed these sentiments: “had producer-director William Berke taken half as much care making the plot development logical as he did in obtaining authentic backgrounds, the picture might have risen above its present exploitation-programmer level”.

The Motion Picture Daily said: “The story […] is strictly coincidental to the presentation of Indian scenes, customs, ceremonies, animals and people. Whether an exhibitor should exploit the attraction on the strength of the Cameron-Romero-Windsor trio or the roar of the tiger, the hiss of the serpent and the trumpeting of the elephant-or both-the job of entertaining the customers is India’s first, last and always. Audiences made acquainted with that fact in advance are likely to like the picture best. […] It’s not much of a story, but it needn’t be, for the purpose it serves.”

Modern critics also tend to agree that the location shooting is what ultimately saves an otherwise perfunctory B-movie. Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings says: “there is a novelty to the scenery that sets it apart from most other jungle movies, so I’d have to say the movie works best as a travelogue”. Mark David Welsh notes that the collaboration with the Tamil studio was a stroke of luck for Robert Lippert: “The advantages for Lippert were obvious; a limited financial risk and a product far removed from his usual cheap, studio bound productions. Instead we get impressive landscapes, lots of extras and genuine wildlife and animal shots as opposed to the usual tired library footage.”

Derek Winnert gives the film a 2/5 star rating: “Though there is a lot of boring dialogue and tedium even in the short 73-minute running time, the stars do well enough, and the film is sufficiently brisk and capable. The woolly mammoths arrive belatedly, which is just as well as they are as lame as expected.”

Gary W. Tooze at DVDBeaver is unimpressed but amused: “The Jungle is one of those off-the-cuff productions made precisely for the Saturday-afternoon youngster trade which goes in for fantastic action and silly improbabilities. This one has ’em all, from hand grenade-throwing monkeys to innocent old pachyderms with fur coats.” Dennis Schwartz is neither impressed nor amused: “The tame jungle adventure tale follows a lame screenplay […], that mixes sci-fi scenes with a jungle safari story. The blend doesn’t work for director William Berke, as things seem inane. It’s also a grueling watch, since it’s so slow-paced and the plot is so absurd.”

As I have stated, I have seen no evidence of the Indian version of this film having been seen by anyone writing film books or about movies on the internet, and it isn’t listed on IMDb, Wikipedia or any other movie resource I have consulted. There’s little chance of it turning up after 75 years, but if it did, it would be very interesting to watch.

Cast & Crew

Director William Berke started his career as a writer of silent westerns in the ealry 1920s, and in the early sound era advanced to producer and director. He directed nearly 100 films between 1934 and 1958, almost exclusively B-movies with 10–12 day shooting schedules and budgets of around $100,000. During the 30s and 40s he was employed by the B-movie units at Columbia, RKO and Paramount, before ending the bulk of his movie career with Robert Lippert in the early 50s. At first, Berke almost exclusively made low-budget westerns, many of them starring Charles Starrett and Russell Hayden as the dynamic duo Steve & Lucky, but he also directed numerous films with westerns star Don “Red” Barry. At RKO he got the chance to produce and direct other genres, and proved particularly proficient with crime dramas, navy films and jungle movies, but was also a capable hand with musical comedies.

William Berke was often teamed up with actors Richard Arlen, Robert Lowery, Jon Hall and Hugh Beaumont – all familiar from science fiction movies we have reviewed on Scifist. He made seven of Columbia’s 16 Jungle Jim movies starring Johnny Weissmuller between 1948 and 1953, and also directed and handful of films starring Tom Conway as the vigilante the Falcon. Between 1953 and 1956 Berke mainly worked in TV, but returned to feature films in 1957, at United Artists. Berke directed only two science fiction movies, The Jungle (1952), filmed on location in India, and The Lost Missile (1958, review), which turned out to be his last movie, as he died of a heart attack on set, aged only 54. His son, Lester Wm. Berke, who worked as an assistant director, finished the movie. Marie Windsor describes William Berke as “such a wonderful little guy” who “worked so hard under terrible circumstances”.

Co-producer of The Jungle (1952) was T.R. Sundaram, or Tiruchengodu Ramalingam Sundaram Mudaliar. He was born in 1909 in a small city outside of Salem, around 400 kilometers from Tamil Nadu’s capital, current-day Chennai, then Madras. Hailing from a wealthy and prominent family (his brother later became mayor of his hometown), he obtained a bachelor’s degree in Madras and then studied textile engineering in Leeds, preparing to go into the family business. However, England changed his perspective on life. Here he met his future wife Gladys, and it was also here he took an interest in the film industry. Returning to Salem in 1933, Sundaram got a job at as a producer at the newly founded Angel Films, before founding his own company, Modern Theatres, in 1935.

For his company, Sundaram built the first studio in South India with all facilities needed to produce a movie, such as a backlot, a music recording and dubbing studio, a large studio hall and a screening theatre. Striving to become the most technically proficient studio on South India, Modern Theatres early on brought over two experienced German cinematographers to work for the studio, who also acted as mentors for the young directors, gaffers and cinematographers from India. Under Sundaram, Modern Theatres produced the first South Indian colour feature film, the first double bill movie and the first movies in the languages of Sinhalese (spoken in Sri Lanka) and Malaylam (spoken primarily in Kerala). At its height, the studio employed around 250 people.

T.R. Sundaram produced over 100 films, even though IMDb lists only 20, and directed many of them himself. Among his best known work is Balan (1938), the first Malayam-language talkie, the fantasy movie 1000 Thalaivangi Apoorva Chintamani (1947), the historical adventure movies Manthiri Kumari (1950) and Sarvadhikari (1951), which were instrumental in establishing M.G. Ramachandran as a superstar, as well as Alibabavum 40 Thirudargalum (1956), the first Tamil colour movie. He also co-produced the US/Indian B-movie The Jungle (1952), an SF/jungle adventure movie starring Marie Windsor, Rod Cameron and Cesar Romero, co-produced with Lippert Pictures. This was the first English-language feature film made in South India, by an Indian movie company. He also produced and directed the science fiction comedy movie Trip to Moon (1967). Sundaram served twice as the chairman of South Indian Film Chamber of Commerce. He is commemorated with two statues and in 2013 got his face on a postal stamp.

Screenwriter Carroll Young started writing Tarzan movies for Sol Lesser in the 40s, and would go on to write around two dozen films, almost all of them jungle pictures. Berke and Young had collaborated on five Jungle Jim movies for Columbia. Young took over writing duties for the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan movie series when Sol Lesser and RKO took over the franchise from MGM. He began his screenwriting career with Tarzan Triumphs (1943), in which Weissmuller fights nazis in Africa. It remained the highest-grossing of Lesser’s Tarzan movies. Young wrote three more Weissmuller Tarzans between 1943 and 1948, and later returned to a last one, starring Lex Barker: Tarzan and the She-Devil (1953). When Weissmuller was deemed somewhat long in the tooth for Tarzan in 1948, Columbia snatched him up for a series of 16 films between 1948 and 1955 featuring hunter and vigilante Jungle Jim. Young wrote seven of these films, with Samuel Newman writing most of the rest of them. In between Young also contributed to a few other films, many of them produced by Robert Lippert. These included the lost world/dinosaur lovie Lost Continent (1951, review), the SF/jungle adventure film The Jungle (1952), filmed on location in India, the mutant/soulless woman SF drama She Devil (1957, review), and a couple of westerns.

Co-writer Orville Hampton worked as both screenwriter, dialogue director, additional dialogue writer and screenplay doctor for both film and TV between 1950 and 1983, and was known as a reliable workhorse. For The Jungle (1952), he was brought in to write additional dialogue. For most of his career, he worked on poverty row B-movies, but did work on more prestigious drama later in his career. He is perhaps best remembered for his work which commented on race relations in the US. His screenplay, co-written with Raphael Hayes, for One Potato, Two Potato (1964), which was an early Hollywood film exploring an interracial relationship, was nominated for an Oscar. In the 70s he also wrote two blaxploitation films, Detroit 9000 (1973) and Friday Foster (1975), which have been singled out for their progressive exploration of race politics.

Hampton was no stranger to science fiction, either. He lent his talents to films like Rocketship X-M (1950, review), Lost Continent (1951, review), Mesa of Lost Women (1953, review), The Alligator People (1961), The Atomic Submarine (1961), The Flight that Disappeared (1961), The Underwater City (1962), as well as the TV series The Six Million Dollar Man (1977) and The All-New Super Friends Hour (1977-1978).

In between films, Hampton also wrote for TV. He contributed to several dozen episodes of Perry Mason, and wrote several episodes for hit shows like Flipper and Lassie. In the late 70s and early 80s he wrote animated shows for Hanna-Barbera.

An interesting character is Ellis Dungan, who is credited as associate producer on The Jungle (1952). Irish-American Dungan was instrumental for the modernisation of Indian cinema in the 30s and 40s, and directed numerous films in the Tamil movie industry in South India. Dungan studied cinematography and movie production at the Unversity of Southern California in the early 30s, and arrived in India in 1935 at the invitation of an Indian co-student who had established himself as a director in the country. What was supposed to be a short visit turned into a 25-year career in Indian cinema, when his friend pulled out of the directorial duties for the Tamil film Nandanar, and recommended Dungan as his replacement. Nandanar (1935) was incidentally the screen debut of future superstar M.G. Ramachandran.

In the 30s, Indian films were still highly influenced by the theatre, and more often than not looked like filmed plays rather than cinematic films, and were dominated by musical numbers. Dungan immediately set to work with modernising Indian cinema by introducing more cinematic screenplays and plots, rather than filmed plays, he worked with actors to get them to file down their theatrical mannerisms and introduced so-called item dances, which became staples of Indian cinema. On the production side, Dungan worked to introduce Western production concepts, such as shooting schedules, shooting hours and call sheets. On a very basic level, he moved Indian cinema away from the static camera to a moving camera, close-ups and multiple camera setups. He introduced the camera trolley, which in Indian cinema got the moniker “Dungan trolley”, he introduced modern movie makeup and other innovations. He did all this without speaking Tamil, and worked with translators – “rush editors” – and had all screenplays translated to English.

While Dungan did many films based on myths, he also introduced Western-infulenced dramatic structures to them. He made one of the first Tamil films with a modern social theme, Iru Sagodarargal (1936), and one of the first films presenting historical fiction with Ambikapathy (1937), for which he looked to Romeo and Juliet for inspiration. The film also contained one of Dungan’s several attempts at pushing the boundaries for intimiacy on the Indian screen: a scene where the romantic lead carries the female protagonist to a bedroom raised many eyebrows. In the process, Dungan also introduced many of Indian cinema’s foremost screenwriters to the industry. His best known movie is Meera (1945), a biopic of the 17th century female mystic and poet Meerabai, in which her poems were adapted into songs. In the title role Dungan cast singer and actress M.S. Subbulakshmi, whose renditions of Meerabai’s poems long stood as the definitive versions of the poet’s work for many Indians. The film was a huge success, and it was dubbed into the majority language Hindi, with a few new scenes, in 1947. The Hindi version became a nationwide success, and the premiere was attended by both Lord and Lady Mountbatten, as well as Jawaharlal Nehru. Dungan also attained some infamy with one of his last Indian movies as a director, Ponmudi (1950). In it, he depicted an intimate romantic scene between the two lead characters, which did not go down well with conservatives, and caused a minor scandal in the press.

He returned to the US in 1950, for personal reasons, and set up a company which produced documentaries and industrial films. However, he returned several times to India, helping Hollywood producers make films in the country. He was an associate producer on Robert Lippert’s SF/jungle movie The Jungle (1952), worked in one capacity or the other on Harry Black and the Tiger (1958) and was second unit producer and cinematographer for Tarzan Goes to India (1962). Marie Windsor says that Dungan was essential for the production of The Jungle: “He knew everybody – he made arrangements with maharajahs, and everywhere we went he arranged the locations. He was so sharp and agreeable, often under crazy circumstances!”

Marie Windsor was born Emily Marie Bertelsen in Utah in 1919, and in 1939 won a beauty contest, which brought her to Hollywood, where she trained as a stage actress, before making her screen debut in 1941. In her early years, she made ends meet through a combination of stage and radio work, a job as a telephone operator and numerous uncredited bit-parts in movies. It wasn’t until 1948 that she got her breakthrough as a featured actor, playing the seductress Edna Tucker in John Garfield’s film noir Force of Evil. With her 5’9 (180 cm) stature, her charismatic, sultry demeanor and her air of intelligence and independence, she made an impression, and the role typecast her as a femme fatale. She would play mysterious, seductive women in several well-regarded noirs like The Narrow Margin (1952), The Sniper (1952) and The City that Never Sleeps (1953). The best known is one of Stanley Kubrick’s lesser known films, the noir The Killing (1956), about a race-track heist, where she had a fairly prominent role.

Windsor’s long and successful career lasted from 1941 to 1991, and she appeared in over 170 films or TV shows. Never quite an A-list star, Windsor nevertheless carried some marquee value in the 50s in particular, although she was such a fixture as a leading lady in B-movies, that she was given the moniker “Queen of the B’s”. She did appear in a number of prestige movies, however, she later said she much rather played leads in low-budget films than bit-parts in A films. In the 50s Windsor gradually shifted to TV work, and appeared on a number of high-profile series, like Lassie, Perry Mason and General Hospital. Apart from her femme fatale noir work, she may be best remembered today for playing the lead in three low-budget science fiction films: The Jungle (1952) Cat-Women of the Moon (1953, review), and The Day Mars Invaded Earth (1963). She had a small role in two episodes of the Batman TV series involving Otto Preminger’s Mr. Freeze in 1966. She has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and was awarded a Golden Boot for her work in westerns in 1983.

Built like a tree trunk and gifted with a relatively narrow range of expressions and emotions, Rod Cameron was more at home in westerns and crime films. Canadian-born Cameron dreamed of becoming a mountie as a child, but instead embarked on an acting career, first trying his luck on stage, and when his career didn’t progress, moved to the West Coast to try and break into the movies in the late 30s. The rough-hewn, 6’4 (193 cm) actor found it slow going, as he primarily worked as a stand-in and insignificant bit-parts. However, in the early forties he started receiving supporting roles in westerns, and got big break in 1943, when he starred in two Republic serials, one western and one African adventure/spy yarn. From there he went to Universal, where he was cast as the lead in numerous low-budget westerns. With his movie career on the slide, he turned to TV in the 50s, and starred in three minor TV series. Despite the diminishing quality of his roles, he kept omn acting until the mid-70s. Cameron appeared in two SF movies: The Jungle (1952) and the British mind control clunker Escapement (1958, review).

By 1952, Cesar Romero was past his most lucrative Latin lover phase in the 30s and 40s, but with his charisma, good looks, deep voice and serious acting chops had racked up enough serious roles to make him a respected character actor, and still clocked in the odd leading man role in B-movies. New Yorker Romero’s Spanish and Cuban heritage, his good looks, charisma and 6’3 (190 cm) stature made him a staple Latin lover in the 30s and 40s. He started his career as a dancer in New York in 1926, and entered Hollywood in the early 30s. Never the most celebrated star of the screen, he was, however, a staple of the Hollywood social life, a “confirmed bachelor”, and an actor who, despite often escorting many female movie stars, managed to to stay clear of any scandals. His earnings from Hollywood were soon good enough for him to support his parents who had gone out of business, and he remained steadily employed by studios big and small, and his “ethnic” appearance held him in high demand for roles as Italian gangsters, Indian princes, Latin lovers and other racialised characters. He smoothly transitioned back and forth between TV and feature films from the fifties onward and all in all appeared in over 200 films or TV shows between 1933 and 1985.

Cesar Romero is perhaps best remembered today for his wacky portrayal of Batman’s arch enemy The Joker in the Batman TV series (1966-1968) and Batman: The Movie (1966). Romero’s Joker was in line with the rest of the series, far removed from the gritty cartoons (which of course weren’t even quite as gritty as they would become in the 80s), his was a campy, over the top performance, just scary enough for the kids and lots of crazy for the adults. Studiobinder points out: “It’s weird to think how method actors gravitate to Joker nowadays. Especially when you consider the first guy who played him couldn’t even be bothered to shave his mustache.” Indeed, Romero refused to remove his trademark ‘tash for the role, and just had the makeup department paint it white. He said in an interview that he had lots of fun playing the role, as it allowed him to do “all the things they tell you that you can’t do as an actor”. Romero was the first on-screen Joker, setting the standards for all to come, and without doubt informed Jack Nicholson’s legendary portrayal in 1989’s Batman. Today Romero is usually ranked as the fifth “best” joker, after the usual suspects: Nicholson, Hamill, Ledger and Phoenix. But to a generation that grew up with the TV show, he is still the ultimate Batman villain. Romero didn’t win many rewards, but he did pick up a Golden Boot for his contribution to westerns in 1986, and was nominated for a Golden Globe for best supporting actor in the 1962 Sandra Dee/Bobby Darin romcom If a Man Answers (1962). He has stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for both film and TV.

Beside Batman the TV series, Cesar Romero appeared in a handful of science fiction movies. In Lost Continent (1951, review), he played a military officer stranded on a radioactive island with dinosaurs, in The Jungle (1952), he appeared appeared as Rama Singh, the majordomo to the Princess of India, chasing prehistoric mammoths, and in the US-Japanese co-production Latitude Zero (1969), he appeared as the evil Dr. Malic, hell-bent on destroying Joseph Cotten’s futuristic underwater utopia. He was also immortalises as the evil mastermind A.J. Arno in three of Disney’s Kurt Russell movies: The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1969), Now You See Him, Now You Don’t (1972) and The Strongest Man in the World (1975).

Of the Indian actors in The Jungle, the most interesting is probably Ruby Myers, who IMDb has rechristened as “Ruby Mayer” for some reason, who was at one point the highest-paid actress in India. An Anglo-Indian from India’s Jewish community, she started acting in movies in the silent era, and quickly became a very popular romantic lead, and one of India’s earliest Eurasian movie stars. For her screen moniker she chose Sulochana, which was the name under which she became most famous, even if she occasionally worked under her birth name. However, the coming of the talkies presented a problem, as Myers worked in Bollywood cinema, and wasn’t proficient in Hindi. She took a year off to learn the language, and returned to the screen in 1932, with great success. Between 1933 and 1939, she was in a romantic relationship with another silent movie star, Dinshaw Billimoria, both in real life and on screen. Their mutual films were hugely successful and Myers became one of the most popular actresses in all of India. However, when the couple went separate ways in 1939, both of their careers also faded. She struggled finding lead roles in the 40s and eventually had to accept her new status as a supporting actress. However, with the exception of a few lean years in the 40s, she was steadily employed until 1980, when she retired. In 1973 she received the Dada Saheb Phalke award, the most prestigious cinema lifetime achievement award for cinema in India.

EDIT May 21, 2025: Updated the article with comments by Marie Windsor from an interview in Tom Weaver’s book “Monsters, Mutants and Heavenly Creatures”. Big thanks to Curt Fukuda for providing me with a copy of the interview.

Janne Wass

The Jungle. 1952, India/USA. Directed by William Berke. Written by Carroll Young, Orville Hampton. Starring: Marie Windsor, Rod Cameron, Cesar Romero, Ruby Meyers, M.N. Nambiar, David Abraham, Ramakrishna, Chitra Devi. Music: V. Dakshamoorty, G. Ramanathan. Editing: L. Balu. Art direction: A.J. Dominic, P.B. Krishnan. Makeup: G. Mannickkam. Produced by William Berke & T.R. Sundaram for Lippert Pictures & Modern Theatres.

Leave a comment