Achille just wants to write science fiction stories, but American scientists want to send him into space and are thwarted by communists and alien clones. Italian comedy legend Totò heads this sloppily written 1958 sci-fi spoof, more interesting for its call sheet than its plot. 4/10

Totò nella luna. 1958, Italy. Directed by Steno. Written by Steno, Lucio Fulci, Ettore Scola and Sandro Continenza. Starring: Totò, Ugo Tognazzi, Sylvia Koscina, Luciano Salce, Sandra Milo. Produced by Mario Cecchi Gori. IMDb: 5.8/10. Letterboxd: N/A. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

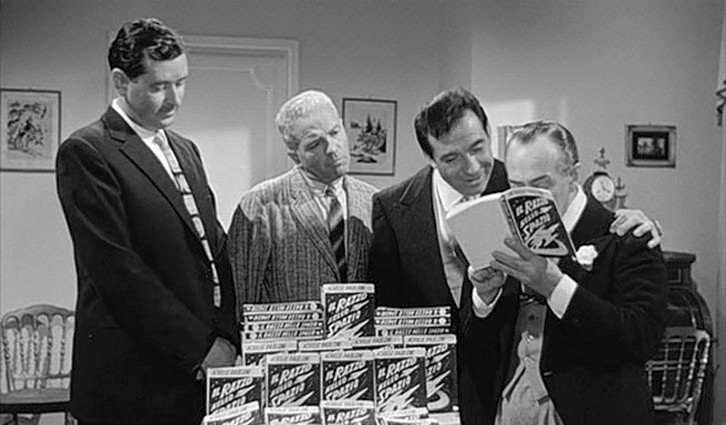

Aliens (represented by animated googly-eyes) are sabotaging America’s attempted moon missions – the last one attempted with a chimp as an astronaut. The US scientists are oblivious to the extraterrestrial meddling, and scratch their heads trying to figure out what keeps going wrong. What is needed, they think, is a human pilot. But this seems impossible, as humans can’t withstand space flight. Enter Achille Paoloni (Ugo Tognazzi), a dim-witted but amiable delivery boy for Italian men’s magazine Soubrette — and wannabe science fiction writer.

So begins the Italian 1958 science fiction spoof Totò nella luna, released in the UK as Toto in the Moon, directed by Steno from a story by none other than Lucio Fulci. The film was yet another vehicle for Italy’s most popular comedian, Totò de Curtis, now in the back half of his career, which ended with his death in 1967.

In Totò nella luna Totò plays Pasquale Belafronte, owner and editor of said men’s magazine. A stingy, overbearing boss, he is also the father of delivery boy Achille’s girlfriend Lidia (Sylva Koscina). However, he firmly opposes their marriage until Achille has become successful and proven that he can support Lidia. Achille, on the other hand, pleads with his father-in-law to print his latest science fiction novel in the magazine, which Pasquale vehemently opposes.

To make a long story a bit shorter: the US scientist catch wind that Achille is the only man on Earth whose blood contains a certain protein, “glumonium”, also found in chimps, which they believe makes him the only man who can travel to the moon. The FBI sends two agents to Rome in order to secure Achille’s services as the first astronaut. But because of the language barrier, Achille thinks that the $100,000 check they hand to him is an advance for the American publishing rights to his novel.

Enter complications. Pasquale tries to con the supposed publishing rights for the novel in hopes of bringing in the profits. Russian/East German spies believe Achille’s novel contains a secret formula for space flight, which they test with explosive results. When both Achille and Pasquale are put through space boot camp, the aliens beam cloning seed pods to Rome, which develop into clones of Pasquale and Achille – that are supposed to take the two Italians’ place on the rocket. Gags ensue, until a mixup leaves the real Paquale and the fake Achille on board the rocket to the moon. After a successful landing, Pasquale argues with a lunarian, which is a ball of glitter, with the result that the lunarian chief turns the Achille clone into a beautiful woman in a silver bikini, with whom Paquale walks off into the lunarian sunset.

Background & analysis

Antonio Griffo Focas Flavio Angelo Ducas Comneno Porfirogenito Gagliardi De Curtis di Bisanzio – or as he preferred to call himself Totò de Curtis, or simply Totò, was, and still is, considered Italy’s greatest comedian. Born in Naples in 1898 to a well-off family, he preferred sports to school and in his late teens got caught by the acting bug. He started out in comedia del’arte in 1917, and soon garnered a reputation as a talented comedian and vaudeville artist, adept at both physical comedy and fast-talking witticisms and puns. He made his screen debut in 1937 with Fermo con le mani, on which he appeared as the character Totò, a tramp modelled on Charlie Chaplin’s famous character. Over his four-decade long movie career, he appeared over 100 films, often playing a variation on his loud, talkative and abrasive character. A large portion of his films can be described as either mild satires or spoofs of popular cultural phenomena. Totò’s trademark was his incessant verbalisation and wordplay, and often the comedy hinged on linguistic misconception. A few of his films had wide international releases and are considered genuinely good pictures, such as Mario Monicelli’s Cops and Robbers (1951), Mario Mattoli’s Miseria e nobilità (1954), co-starring Sophia Loren, and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966). Most of his movies, however, are considered formulaic low-brow farces in which plot development and cinematic values are sidestepped in favour of letting the great maestro take the spotlight with his tour-de-force performance. Totò nella luna falls in the latter category.

Despite doing a thorough search, I have found little to no production information on the film, appart from what can be gleaned from IMDb. It was filmed in autumn of 1958 at De Laurentiis Studio in Rome, and was directed by comedy specialist Stefano “Steno” Vanzina, a frequent collaborator of Totò’s. The story was developed by Steno and a young Lucio Fulci, a far cry from his reputation as a horror master, and the script was finished by Steno and a few other collaborators. And that’s pretty much all I can tell you about the production.

The movie was released shortly after Italy’s first science fiction film in sound, The Day the Sky Exploded (1958, review), and some later commentators have speculated that it was a comedic comment upon that film. However, since there is no reference in the plot to anything remotely resembling The Day the Sky Exploded, I suspect the script for Totò nella luna was probably finished before the serious film had premiered.

Other films are more clearly referenced in the plot. Of course, the pod people and the duplicates represent a spoof of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), and in general Totò nella luna references the cold war space race subgenre, complete with a shady communist agent and his femme fatale sidekick trying to sabotage West’s space programs and/or steal secrets. Destination Moon (1950, review), with its genre-defining take on the first attempted moon flight is sometimes mentioned as a source of inspiration. The film I think it mostly resembles is Roger Corman’s War of the Satellites (review). The similarities are almost uncanny. Both films feature aliens interfering with Earth’s attempts at conquering space through asserting some mysterious force over rockets launched into space. In both films alien duplicates of astronauts are created in order to sabotage the space flight, and in both films the aliens communicate to Earth with animated spirals and grave voices speaking from the void. War of the Satellites didn’t premiere in Italy until November, 1958, but is it possible that Steno or Fulci might have read a review of the film in a trade magazine before it premiered? There’s a fairly long scene with Achille and Pasquale stuck in a freezer, preparing for the chill of outer space, which according to Ennio Bispuri’s book Totò principe clown is simply a rehash of a scene in another Totò movie also scripted by Steno, Due cuori fra le belve (1943). As Phil Hardy points out in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies, even the setup of a mild-mannered author trying to get his stories published in his magazine run by a despotic editor seems to be lifted from another film, namely Jean Renoir’s The Crime of Monsieur Lange (1936).

Totò nella luna holds together fairly well in the film’s first third, when it deals with the confusion stemming from the language barrier between Achille and the FBI representatives, and Achille believes that when the Americans say they want to “launch” him, they are talking about a book launch. However, it gets bogged down with the pointless spy plot that adds nothing to the plot, and the doppelgänger theme is never utilised properly. The ending of the film, while it gets the plot fairly well tied up, feels like a letdown. Totò ends up talking to a glittering ball, and Achille becomes a best-selling author off-screen, and it is not a satisfying finale to the space adventure the movie has been building to, even considering this is a spoof.

As far as the comedy goes, I can’t pass definitive judgement. First, it is always difficult to evaluate verbal comedy in a language you don’t understand, even if you have proper subtitles. Puns and nuances are lost in translation, and much of the humour is often based on cultural phenomena, that translate poorly across geographical and cultural boundaries, especially when they are experienced across the chasm of almost 70 years. It didn’t help that the subtitles that came with my download were severely lacking – the subtitles disappeared for at least half of the film’s runtime, so while I was easily able to follow the plot, the verbal comedy was lost on me for long stretches.

I did catch the central premise of the film, the misunderstanding between the Americans and Achille – a fun premise, and one that could have been better developed into the rest of the movie. Italian critics say that it is Totò that carries the film in his shoulders, and that he has a couple of very funny and poignant monologues – including one where he imitates Mussoloni and Hitler. This, unfortunately, passed by me. I did catch smaller moments, like when Soubrette can only afford one shoe and one stocking for their pin-up model, and the financier says that for a picture of a girl with only half of her clothes, they will only pay half the fee, or when Totò gets his space girl in the end, and muses that artificial girls don’t come “with the problem of pregnancy”. The film is full of these kind of verbal jokes, some of which feel rather stuffy, especially as the girls that Totò ogles are in their early 20s and Totò was 60 by the time the movie was made.

The situation comedy is easier to understand, and could be descirbed as sometimes amusing and sometimes flat. One of the standing gags in the last third of the film is that the alien copies of Pasquale and Achille are defect, and are unable to move or speak properly, making them seem like complete nitwits. Unfortunately, Steno & Co are not able to incorporate this into the plot in any meaningful way, so it just becomes and empty gag. As far as spoofing goes, the elements are there, but to make this a genuinely funny and searing spoof, the tropes would have needed to be more sharply and intelligently integrated into the script.

Technically and visually Totò nella luna leaves more to be desired. It is competently filmed – Steno was a seasoned professional – but in a film spoofing science fiction, more effort could have been put into design and special effects. The only visual effects of the movie, save some animation, are the shots of the pods turning into human clones, and a scene in which the duplicates and the original Achille and Totò appear side by side. The first is done through simple cross-dissolve and the second one is just classic split-screen + body doubles. The cockpit of the rocket is nothing to write home about and a weightlessness scene is laughably bad – it’s just Totò filmed from the chest up flailing with his arms, pretending to be floating. And of course, the glitter ball at the end is a sad excuse for an alien.

As far as the acting goes, this movie provides mugging at the highest level from almost all involved.

Totò nella luna is a film that really is only worth watching for Totò completists. It’s not terrible, in fact it is quite amusing and even funny in parts, even if you can’t appreciate Totòs verbal acrobatics. But you probably need to understand Italian to fully appreciate it. As for the rest of us, the script just isn’t up to specs.

Reception & Legacy

Totò nella luna premiered in later November, 1958, and seems to have had a limited international release – IMDb lists release dates for the UK and Portugal in 1959 and 1960. It was not among Totò’s most popular films – it ranked #73 in popularity for the season, and grossed a modest 368,650,000 lira, while the top grossers made well over one billion lira. While it wasn’t a downright flop, its unimpressive box-office returns may explain why a planned follow-up, “Totò in orbita”, was never produced.

The film was panned by contemporary Italian critics. Leo Pestelli in La Stampa wrote: “Fat jokes, cheeky double entendres, lack of rhythm, lack of inventiveness, are the characteristics of Totò nella luna, a rushed product of our commercial cinema”. However, Pestelli concedes that the back-and-forth between Totò and Ugo Tognazzi is “fairly entertaining”. An anonymous critic in El Messaggero critisised the “tenuous plot” built around Totò’s jokes and puns, and opined that the film “struggles to keep upright”. And Arturo Lanocita at Corriere della Sera said: “Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon, at the dawn of cinema, was funnier and more innocent”.

The film is included in Phil Hardy’s The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies (1984), but only with a plot synopsis and no critical assessment.

Website Cinematografo cites an undated review by Massimo Bertarelli in Il Giornale, which describes the film as “directed with the left hand by the ever-so-disengaged Steno, built on kindergarten double entendres, predictable jokes, and space opera-like paraphernalia”. Bertarelli notes that Totò does showcase a few flashes of his talent, but feels that his duets with Tognazzi are largely wasted opportunities.

In his book Totò principe clown, Ennio Bispuri describes Totò nella luna as “a fourth-rate farce (especially in the second half), packed with clichés and stale situations that aren’t even funny”.

Some modern critics are more positive. Giuseppe Rausa calls the movie “a lively and successful satire of science fiction cinema”. Marcel M.J. Davinotti writes that Totò is “in splendid form”, and that the first half of the film works comparably well: “If it weren’t for the poor script and the unexpectedly sloppy direction, the first half would be excellent”. However, the screenwriters, feels Davinotti, don’t have their pulse on science fiction, and thus the quality of the movie declines in the second part.

Gary Westfahl writes in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction that “while the film has interesting implications, it is not particularly funny”. Unsurprisingly, this film has few reviews by writers outside Italy – but one can almost always count on Dave Sindelar at Fantastic Movie Musings and Ruminations, and Mark David Welsh, to have seen even the most obscure science fiction movies. This time, however, Sindelar has prescious little to say, as he has watched the film without subtitles: “It looks fun enough”. Welsh, however, seems to have found a subtitled copy: “Of course, this is all very silly, with the humour drawn in broad strokes and plot developments largely predictable. […] The film is firmly earthbound for much of its running time before finally going into orbit in the last fifteen minutes. Unfortunately, by that point, it has overstayed its welcome a little with an insufficient number of events and too many formulaic situations to consistently engage the funny bone. […] Harmless, if somewhat lightweight, comedy vehicle that raises a smile or two.”

Cast & Crew

Few of the people involved in this movie are of any greater interest to science fiction, so I’ll keep it fairly short (for this blog) this time. It is worth mentioning, though, how the credit sheet shows what a melting pot for talent Italian cinema was in the 50s and 60s. Just the writing team alone, on this silly little low-budget comedy, consists of four giants in Italian cinema: Steno, Lucio Fulci, Ettore Scola and Sandro Continenza. The film featured budding comedy star Ugo Tognazzi and two of Italy’s great leading ladies, Sylva Koscina and Sandra Milo. Producer Mario Cecchi Gori went on to earn an Oscar nomination, procuction designer Giorgio Giovanni and costume designer Ugo Pericoli to win a Silver Ribbon each, and production manager Pio Angeletti became a producer who was awarded with a lifetime Donatello award.

I have described Totò’s background above, so I won’t go into greater detail about his career here. But one might add that by the time Totò nella luna was made, the star had suffered a serious eye infection a couple of years earlier, which cost him most of his eyesight. However, this mainly affected his live touring, which he had to give up, but not so much his film work. The main difficulty was his inability to stand bright studio lights for longer periods, which meant directors had to keep shooting schedules short, avoiding meticulous blocking and multiple setups in favour of shooting any given scene in as few takes as possible and counting on Totò’s comedic timing to make it work.

He appeared in numerous films in the late 50s and 60s, including many of his all-time classics, like The Law is the Law (1958), Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), Treasure of San Gennaro, and not least Pasolini’s The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), described by Roger Ebert as “a whimsical fantasy about Christianity and Marxism”. The film was a rare opportunity for the actor to show off his dramatic skills and it awarded him a Silver Ribbon for best actor, one of Italy’s most prestigious film awards. During his career he was nominated for a Silver Ribbon thrice and won twice. He was, however, never nominated for the country’s most prestigious award, “the Italian Oscar”, the David di Donatello award, which some commentators have perceived as a bit of a snub, be it that the award was founded in 1955, when Totò was past his prime in terms of popularity. Totò died in 1968, and due to popular demand, three funeral services were held, in three different cities. Totò nella luna was his only run-in with science fiction.

Writer/director Stefano Vanzina, mostly working under the pseudonym Steno, is by no means considered one of Italy’s most prestigious directors, but the prolific Rome-born busybody left behind him a vast legacy of popular comedies and was instrumental in building the careers of many of Italy’s most famous comedians. His career stretched between 1939 and his death in 1988. He is probably best known for the drama/comedy Cops and Robbers (1951) and the crime movie Execution Squad (1972). The first one is a heart-warming caper comedy with a philosophical humanistic undercurrent about a police detective and a thief befriending each other while the one is trying to hunt down the other. The film starred two of Italy’s comedy greats, Totò and Aldo Fabrizi. Totò received a Silver Ribbon for his work in the movie and Fabrizi was awarded as “best foreign actor” at the Finnish Jussi award ceremoni. The movie was nominated for the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. Execution Squad was a rare depart from comedy by Steno – highlighted by the fact that he directed the movie under his full name. A raw, hard-boiled crime movie in the vein of the American and French crime thrillers of the late 60s and early 70s, the movie is often regarded as one of the milestones in the development of the so called poliziotesco or Italo-crime movie of the 70s. The film earned Steno his only major award, that of best director at the San Sebastián Film Festival. Apart from Toto in the Moon (1958), he also wrote and directed the sci-fi comedies Un mostro e mezzo (1964), Dr. Jekyll Likes Them Hot (1979) and Urban Animals (1987).

The movie was co-written by Lucio Fulci, Ettore Scola and Sandro Continenza, all three giants in the Italian movie industry, in quite different ways. In the 70s, Fulci became the most controversial of the Italo-gore directors Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), Zombie (1979), The Beyond (1981) and The New York Ripper (1982). While Fulci was reviled and banned, Scola became one of Italy’s most prestigious writers and directors, racking up several wins at Cannes, Venice, Berlin, etc. He is perhaps best known internationally for the romance drama A Special Day (1977), set in Berlin on the brink of WWII. Sandro Continenza, on the other hand, was an extremely prolific writer of B-movies, most noted today for co-penning the script for Enzo G. Castellari’s original Inglorious Bastards (1978).

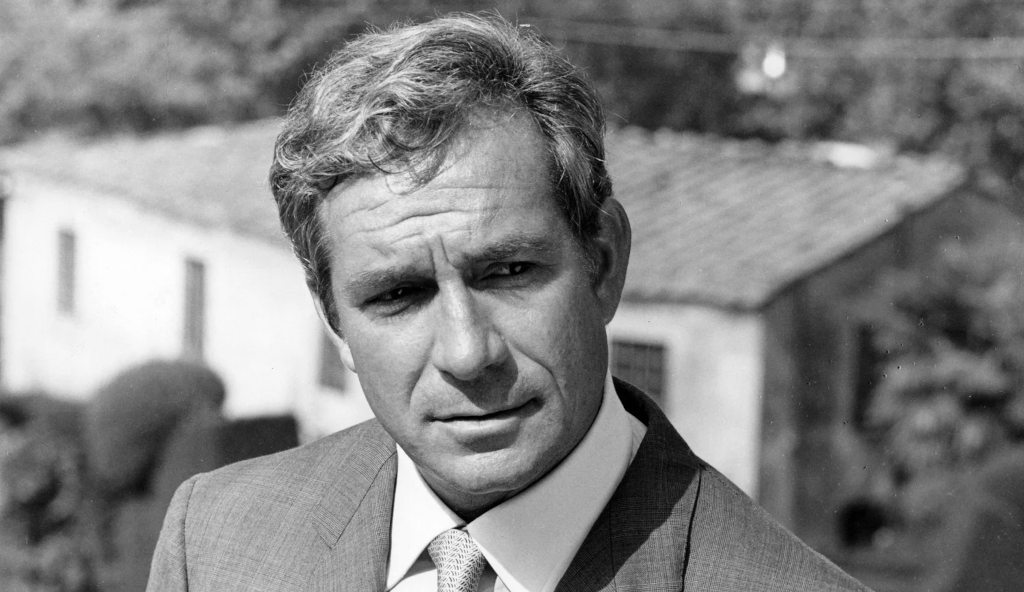

At the time of the release of Toto in the Moon, Ugo Tognazzi was already a well-known comedian, primarily on the strength of his performances on state owned RAI TV shows. However, with his turn in The Fascist (1961), he became one of the top movie stars in the country. Tognazzi appeared in a number of critically acclaimed movies. My Friends (1975) sweeped the Italian award tables and The Big Feast (1973), La terrazza (1980) and The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981) all picked up awards at Cannes. International audiences will know him best from playing the lead in La cage aux folles (1978) – and sci-fi fans might recognice him as Mark Hand in Barbarella (1968). Tognazzi received a best actor award at Cannes for his work in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man and was nominated for a Golden Globe for his role in The Climax (1967). He also worked as a director, and his film The Seventh Floor (1967) was nominated for best picture at the Berlinale. He also directed and starred in the dystopian movie Il viaggiatori della sera (1979).

Zagreb-born Sylva Koscina was already an established leading lady in 1958. While she primarily performed in comedies, the best known of her early roles is probably that of Steve Reeves’ fiancée in the genre-defining Hercules (1958). While never a bona fide A-level star in Italian cinema, Koscina nonetheless was in demand for leads in B-movies and supports in A-movies. In the 60s Koscina appeared in several international productions, and even had a stab at Hollywood. In order to annouce herself in the US, she, like a good number of actresses of the era, appeared in a nude photoshoot for Playboy. It seems to have paid off, as she was quickly paired with a collection of Hollywood’s biggest leading men. She appeared opposite David McCallum in Three Bites of the Apple (1967), Kirk Douglas in A Lovely Way to Die (1968), Paul Newman in The Secret War of Harry Frigg (1968) and Rock Hudson in Hornet’s Nest (1970). She also starred in the British crime mystery Deadlier Than the Male (1967). Her status as a sex symbol was also exploited in Jesùs Franco’s Marquis de Sade: Justine (1969), L’assoluto naturale (1969) and Mario Bava’s horror movie Lisa and the Devil (1974). Despite having acted in movies since 1955, she was nominated as “best new face (female)” at the 1967 Laurel awards, in a line-up that included Sandy Dennis, Vanessa Redgrave, Raquel Welch, Nancy Sinatra, Britt Ekland and Faye Dunaway.

However, by the 70s Sylva Koscina’s film offers became less and less lucrative, and after having put most of the money she earned in an extremely expensive mansion, she struggled financially. She kept acting, though, until her death at only 61 years of age in 1994. Totò nella luna was her only sci-fi.

IMDb has such a fun and well-written biography of Sandra Milo by Gary Brumburgh that I must quote it: “During the 1950s and 1960s bosomy, scintillating, dark-haired Tunisian leading lady Sandra Milo played bored patricians, manipulative mistresses and other enticing ladies of questionable morals with typical sensuous flare in scores of Italian and French productions.”

In Totò nella luna Milo plays a supporting character as the seductive Russian spy Tatiana, but she soon worked her way up to leading lady status. She reached her peak in the first half of the 60s, appearing opposite Jean-Paul Belmondo in the crime caper The Big Risk (1960), in two of Antonio Pietrangeli’s successful comedies, Adua and her Friends (1960) and The Visit (1963), as well as in two of Federico Fellini’s masterpieces: 81/2 (1963) and Juliet and the Spirits (1965). She won Silver Ribbons for her performances in both Fellini films. While she continued acting up until her death in 2024, she never topped the critical or commercial success of her early 60s movies. According to a Guardian obit, “she was known latterly more for her appearances in gossip columns and on television as a presenter, talkshow guest or reality-show participant”. Sandra Milo picked up a lifetime Donatello award in 2021. She did no other sci-fi.

As per susual in Italian films, many of the supporting actors were dubbed by other voice actors. Worthy of mention among the voice artists is Maria Pia Di Meo, who dubbed numerous international films, and has become the official voice of Meryl Streep in Italy, and has won numerous awards for her dubbing of Streep in films like The Devil Wears Prada (2006), Julie & Julia (2009) and August: Osage County (2013). She dubbed Sylva Koscyna in Toto in the Moon. She also dubbed most of Ingmar Bergman’s movies.

Janne Wass

Totò nella luna. 1958, Italy. Directed by Steno. Written by Steno, Lucio Fulci, Ettore Scola and Sandro Continenza. Starring: Totò, Ugo Tognazzi, Sylvia Koscina, Luciano Salce, Richard McNamara, Jim Dolen, Sandra Milo, Agostino Salvietti, Giacomo Furia, Renato Tontini, Anna Maria Di Giulio. Music: Alexandre Derevitsky. Cinematography: Marco Scarpelli. Editing: Giuliana Attenni. Prodiction design: Giorgio Giovannini. Makeup: Goffredo Rocchetti. Sound: Rocco Roy Mangano.

Leave a comment