A maverick pilots his rocket plane into space and comes back as a vampiric monster. This 1959 low-budget US/UK cooperation takes its inspiration from The Quatermass Xperiment, but lacks its predecessors quality, atmosphere and intelligence. Still, it’s a competent and fairly entertaining programmer. 4/10

First Man Into Space. 1959, USA/UK. Directed by Robert Day. Written by John Croydon, Charles Vetter, Wyott Ordung. Starring: Marshall Thompson, Marla Landi, Bill Edwards. Produced by Richard Gordon et.al. IMDb: 5.4/10. Letterboxd: 2.8/5. Rotten Tomatoes: N/A. Metacritic: N/A.

Test pilot and maverick playboy Dan (Bill Edwards) wants to be the first man into space. So much so, that he routinely ignores security instructions and takes his test rocket plane higher into the atmosphere than his superior – and brother – Chuck (Marshall Thompson) gives him permission to. After at near-fatal test flight with the Y-12 plane, Dan ignores debriefing and health procedures and heads straight home to smooch with his girlfriend Tia (Marla Landi). That’s the straw for Chuck, who wants his brother taken off the program. But he is nixed by the military brass and politicians, who immediately assign Dan to the next phase with a new rocket plane, the Y-13.

First Man Into Space (1959) is a US-UK co-production from low-budget producer Richard Gordon, partly based on a story treatment by Wyott Ordung, which ran as a double-bill with the Japanese import The Mysterians (1957, review) in the US. Generally considered a notch above many of the sci-fi B-movies flooding theatres in the late 50s, it was another commercial success for Gordon and his co-producers.

So, despite the misgivings of Chuck and Tia, who is afraid Dan will get himself killed, Dan is set to pilot the next high-altitude plane, the Y-13. But not before Chuck has the top space medical adviser, Dr. von Essen (Carl Jaffe) put his space psychologists to work on Dan in order to get him to understand that he needs to follow orders and procedures. A fruitless effort, it turns out, as Dan once again puts his dream of being the first man into space ahead of regulations, and pilots his plane up above Earth’s atmosphere, succeeding in his plans. But once he enters space, things start to go horribly wrong. His plane is bombarded by mini-meteorites, or some kind of space dust. He loses control of the plane, but is somehow able to make it back to Earth, where he parachutes out or the cockpit – and disappears into the woods in New Mexico.

Soon both cattle and people in the vicinity of the crash start getting killed – with slashes to their throats coated in a strange, silvery dust. Meanwhile Chuck, von Essen and a Captain Richards (Robert Ayres) try to make head and tails of a weird, seemingly impenetrable crusting that has built up on the cockpit of the plane, coming to the conclusion that it is caused by the meteoric dust that Dan enountered. Of course, while the audience has no problem putting two and two together, it takes these top brains an unreasonably long time to figure out that Dan has been turned into space monster.

When they finally do, they figure out that some cosmic radiation has altered Dan’s metabolism, giving him a constant need to replenish his blood, which is why he keeps killing – and making Earth’s atmospheric pressure hostile to his new body. Apparently, monster Dan has figured out the same thing, as he returns to the space lab, and heads for the pressure chamber. Chuck and von Essen keep the military from killing Dan, and von Essen guides him (he having now lost much of is reasoning capabilities) to the chamber via the building’s speaker system. Dan, now encrusted in a thick layer of meteorite dust, is unable to work the controls of the pressure chamber, so his brother heroically gets into the tube with him in order to help. But will von Essen and Chuck be able to save Dan, or will he become a martyr of science, a hero who sacrificed himself in the name of progress and the advancement of the human race? And and in that case, will Tia, as per ususal with the brides of movie monsters, switch from Dan to Chuck, who has been set up as the fallback romantic interest for the entirety of the movie? I think we all know the answers.

Background & Analysis

Richard Gordon was a British low-budget producer who made something of a career in New York, where he set up his own company Gordon Films, specialising in importing films to the US, but also co-producing in particular British movies and securing their distribution in the States. The company had a hit with their films The Haunted Strangler (starring Boris Karloff) and the SF movie Fiend Without a Face (review) – the one with the hopping brains – in 1958. The movies were distributed by MGM in the States and worldwide outside of Britain, and they had brought in a decent profit, so when Gordon presented to them the idea of First Man Into Space, the company was game. The reported budget for the film was $131,000, or around £100,000.

According to Tom Weaver’s interview with Gordon, the original idea for the film came from Gordon’s partner at the time, Charles Vetter. At the same time, Gordon was approached by his brother Alex Gordon, who worked as a producer at American International Pictures alongside people like Roger Corman. Alex would often send scripts to Richard that AIP had passed on, and such was the case with a story treatment by Wyott Ordung, the man responsible for Robot Monster (1953, review) called “Satellite of Blood”. The story was written in 1957, just after Sputnik was launched, and there was a while when all low-budget science fiction films involved things called “satellites”, regardless of whether they were actually rockets, UFO’s or something else completely. Richard liked the story, and handed it over to Vetter who incorporated some of Ordung’s ideas with his own. Major rewrites were apparently also done by British producer John Croydon. How much of a script there actually was is a matter of some debate. In another Weaver interview, director Robert Day claims there wasn’t much of it, and that he and Vetter would spend each evening after shooting with writing the dialogue for the next day. Director Day was a journeyman workhorse who had previously directed The Haunted Strangler for Gordon.

Gordon’s speciality was co-producing films in Britain through a company called Amalgamated Pictures, headed by John Croydon. Because of the British quota system, UK productions got a financial grant as a way of strengthening British film productions, a fact that several Hollywood production and distribution companies took advantage of as a way to co-produce films in the UK with a subsidised budget – and distribute them in the US. The terms of the grant stated that the film had to be shot in the UK and it had to have a British producer and director, which is why Gordon’s name never appeared in the credits, rather the production credits went to his line producers, in most cases John Croydon, at Amalgamated.

On the other hand, Gordon and the American distributors wanted recogniseable American actors in the lead role(s) in order to market the movies in the US. In the case of both Fiend Without a Face and First Man Into Space this actor was Marshall Thompson, a boyish leading man with some marquee draw in the 40s, whose career was a bit on the slide in the late 50s. First Man Into Space would have represented a little bit of a casting challenge, as the film was set in the US, and Gordon didn’t have the money to fly over more American actors. Thus the rest of the cast is made up of American expats, British actors who could do a convincing US accent, or simply European actors residing in Britain, who would have spoken with a “foreign” accent regardless of whether they lived in the US or UK. Pilot actor Bill Edwards was born in Canada, but had relocated to London, Robert Ayres was an expat American, Marla Landi was Italian, Carl Jaffe German, Bill Nagy Hungarian, and Roger Delgado, playing the Mexican consul, was born in Britain to Spanish and French parents, which explains why his Spanish accent occasionally veers off into a French ditto.

The movie was primarily shot in England. The majority of the studio work was done in a mansion near Hampstead Heath outside London, according to Gordon because the area passed for Central Park in New York. Some second unit photography, like car chases and establishing shots, where shot on location in New Mexico, as well as around a US air base in Brooklyn, NY. But some location shooting was also done in Britain, sometimes lending New Mexico an oddly forested feel. This second-unit footage was provided by Alex Gordon, who sent a cameraman to capture authentic American locales. But apart from a few forests that look decidedly northern European and a mispronunciation “Alvarado”, I as a non-American buy the setting, and if someone told me it was filmed in the US in its entirety, I would not have protested. Planes and rockets on display are stock footage, plus a little bit of miniature model work.

Those who know their 50s science fiction films will recognise the British classic The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review) as a strong influence on First Man Into Space, with its central premise of an astronaut returning from space transformed into a monster. Apart from the central premise, there are also visuals that echo Quatermass, such as the astronaut/monster lurking in the bushes at night and a break-in at a hospital, with broken vials and bottles as a result. First Man Into Space is different enough, though, as to not feel like a retread of its inspiration. In a way it feels like a mashup of the British and the American 50s sci-fi movie. The first part has an almost documentary and matter-of-fact feel, and the on-screen happenings don’t seem too far removed from actual high-altitude testing that was going on at the time. The fact that the story revolves around a plane and not a rocket also gives it a distinctly British air: the Brits had been obsessed with experimental aviation films ever since David Lean’s sci-fi adjacent The Sound Barrier (1952).

Another peculiarly British trope is that their space adventures in the 50s never reached the moon or another planet, but were stuck just beyond Earth’s atmosphere, if they even got out of it. British space films also tended to be decidedly Earth-bound, often placed at some secret experimental base, revolving as much around the soap-opera-like personal dramas of the aviators and scientists involved as they did around the SF content of the movies. First Man Into Space is only a minor offender in this regard, but we do have the strained relationship between the two brothers and in turn their relationship with Tia, and the attempt by Chuck to influence his brother through Dr. von Essen, who also happens to be Tia’s boss (she works with calculations in the pressure chamber). On the other hand, the second part of the film, with authorities and scientists hunting down a space monster, is much closer in tone to AIP’s monster movies and the likes.

First Man Into Space carries out this marriage between styles slightly awkwardly, but still manages to stay afloat. The story progresses in a fairly logical manner, and while there is a severe dip in energy in the middle of the film when the audience is waiting for the characters of the movie to figure out what we already know, it is all-in-all competently put together.

The premise of the film is, naturally, hogwash. But one should remember that at the time the film was made, scientists were still figuring out how creatures of flesh and blood would react to travelling outside of Earth’s atmosphere. The idea that something terrible would happen to the human body, or that ity would bring back some alien parasite from space was a pretty common trope in pulp fiction, and, of course, the central premise for the groundbreaking TV show The Quatermass Experiment (1953, review) and its movie adaptation. First Man Into Space is, however, marred by the same problem as so many other similar films: at first the protagonists are unable to put two and two together even though the answer is staring them in the face, and then, suddenly, they figure out exactly what has happened to Dan right down to the molecular level by making giant leaps in conclusion based on almost no evidence or even scientific logic.

More importantly, perhaps, the film is a snapshot of a short period of time in the beginning of the space race, between the first satellite and the first human in space. As Richard Scheib at Moria Reviews writes, the film “seems to bubble with a tremulous anxiety about the terrors that await mankind as it steps over the threshold into space. There seems a vast underlying fear to the film that conquering space may end being too huge a task for mankind to take on.”

As a dramatic presentation, the film leaves more to be desired. It shares some of the problems of Gordon and Croydon’s Fiend Without a Face. In particular, both films are extremely slow to get going and pad out good parts of their first halves with stock footage and shots of cars driving and people walking from cars and through doors. Both films also get stuck in romantic and personal soap-opera level subplots that have little to no bearing on the plot. First Man Into Space is a lesser offender. The first half is more driven and the personal subplot not quite as tacked-on. The film also picks up speed a little earlier than Fiend Without a Face, which only really kicks in to gear in its last 10 minutes. In almost all regards, First Man Into Space is a better picture. However, Fiend Without a Face is vastly more memorable because of its magnificently pulpy ending – the grand guignol sequence with evil hopping brains getting blasted into pulp with the help of stop-motion animation and raspberry jam. First Man Into Space also has an ending that’s better than the rest of the film. In particular the scene where monster Dan is being guided through the research station by voice command is well filmed, drumming up some genuine tension and atmosphere. However, once Dan gets into the pressure tank, the movie unfortunately grinds to a halt with too much talk and too little action. The idea is neat, and would probably have worked better as literature than as film.

The effects are impoverished but better than much of what was coming out of the low-budget end of Hollywood. A combination of stock footage of actual rocket planes and miniature photography make the aviation/space sequences – not exactly realistic, but good enough for a movie like this. The monster suit is crude but surprisingly effective, especially the one unblinking eye is quite creepy. The encrusted plane cockpit has a really nice, gnarly look to it as well. The effects were designed by the same duo that made the memorable brains in Fiend Without a Face: Flo Nordhoff and Karl-Ludwig Ruppel, and the presumably also designed the monster suit. According to director Robert Day, it was made from “some sort of plastic material”, presumably rubber or latex. Richard Gordon tells Tom Weaver that co-lead Bill Edwards played the monster – as Gordon couldn’t afford a separate suit actor. It was “very hot and uncomfortable”, and Edwards could only wear it for short periods at a time, as he wasn’t getting enough air.

Half-decent effects can’t hide the film’s low budget, though. With the exception of the pressure lab, interiors are cramped and drab, setups are plain and uninteresting, and the whole affair has all the distinct marks of a low-budget B programmer. This includes the script, which does occasionally feel as if it was written on the fly.

Acting-wise, the film is OK. Bill Edwards has a suitable mix of annoying and charming as the hotshot pilot. Like Arthur Franz, whom we have recently reviewed in Monster on the Campus (1959, review), Marshall Thompson was a minor B-movie star who projected a sort of homely charm, somewhat at odds with the authoritative by-the-book military type he plays in First Man Into Space, but he compensates with likeability. Marla Landi, a fashion model and actress who arrived in the UK in 1954, is in the film more to provide a bit of exotic beauty than because of her acting talents, but like Thompson, she gets by nicely on the strength of her charm. Robert Ayres is suitably staunch and stiff as the representative of the military brass and Carl Jaffe was always reliable as white-haired scientist.

The first half of the film is slightly more original than the second, although this kind of thing had already been done, especially in British SF, for a decade. It is also plodding, dragging out scenes and shots for too long. The semi-documentary approach of the first half also doesn’t quite gel with the monster hunt of the second. The second half isn’t all that much better – it is derivative and sometimes rather silly. It is another one of those films in which the audience quickly figures out what is going to happen or what has happened, and then must spend the rest of the movie watching the investigators play catch-up. However, whichever half you like better will depend on your preferences. First Man Into Space is definitely not a terrible film. It is competently made, decently acted and even tries to some extent to develop the characters. It has its moments, but is just overall too programmatic and predictable – and was so even in 1959.

Reception & Legacy

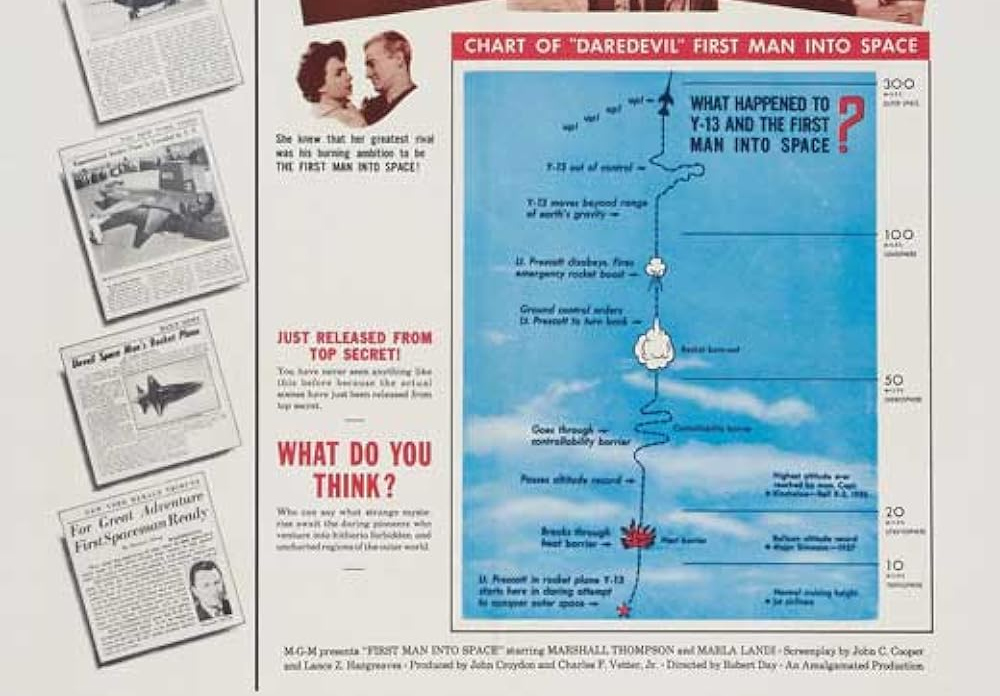

First Man Into Space premiered in February, 1959 both in the UK and the US, although it didn’t get a wide release in the States until May, when MGM paired it with the Japanese import The Mysterians (1957, review). Producer Gordon tells Tom Weaver that MGM wanted to downplay the horror aspects of the film in order to give it a wider appeal. Thus posters and marketing materials doubled down on the film’s title and gave the movie an almost documentary-like marketing campaign, promoting the movie as a film that portrayed accurately the first spaceflight of a human being. One poster even printed a graph of Dan’s flight, and omitted the monster completely – reversing the usual low-budget monster movie trend where the monster was always the selling point. Surely this must have confused some of the patrons when the movie suddenly shifted into schlock mid-way through. However, the strategy apparently paid off, as First Man Into Space earned over $300,000 at the US and Canadian box office and around the same amount in the rest of the world – netting MGM a small profit. The movie was long unavailable for home viewing, but got a DVD release in 1998, and was included in a Criterion Collection … uh collection … in 2007.

Contemporary trade press generally offered the movie mild praise. British Monthly Film Bulletin somewhat surprisingly gave the film its rare (for a sci-fi film) “above average” rating, writing: “Competently made, and with one eye on the American market, this highly coloured Science Fiction thriller presents its playboy-into-monster character sympathetically, while the make-up is uncommonly skilful and survives some strongly lit close-ups with no loss of conviction. The dialogue and an eerie climax are quite compelling, and although the film is still far from having achieved Ray Bradbury quality, it represents a move in the right direction.”

In the US, trade magazines tended to focus on the film’s box office potential, generally opining that First Man Into Space, with the right kind of marketing, could potentially do quite good business. Film Bulletin gave it a 2+/5 business rating, writing: “Director Robert Day knows how to make the most out of his scenes of suspense, while the dialogue […] manages, for the most part, to keep a sense of plausibility about things”. The Motion Picture Exhibitor particularly liked the first half of the film, and thought acting, direction and production were “okay”. Harrison’s Reports likewise preferred the first half of the movie, dealing with the test flights, but after that, the review stated, “the story deteriorates into familiar horror stuff”.

The always enthusiastic Motion Picture Daily thought First Man Into Space was “reasonably well done” and said that “implausibilities in the story are compensated for by generally excellent performances, tight direction and interesting technical details”. While MPD’s often positively slanted reviews should be taken with a grain of salt, the generally sharper Variety also gave the movie thumbs up, calling it “a good entry in the exploitation class”. Critic “Powe” continued: “It has excitement and horror. It is generally well-made and suffers only from a tendency to get cosmic in its philosophy as well as in its geography.”

Phil Hardy’s Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies once again, as so often with these minor films, gets about half of the plot right, suggesting that the person who wrote the entry had either not seen the film or based their entry on half-remembered recollections.

In his book Keep Watching the Skies Bill Warren claims that the film “did look exceptional at the time”, a statement that isn’t quite backed up by the above cited trade press reviews. Warren continues: “Sensible, sober and realistic, it was better than other films released then. However, it is indeed dated”.

Modern critics seem divided on the merits of First Man Into Space. DVD Savant Glenn Erickson does credit it with being a “clever knock-off”, but then goes on to lament its “humorless script”, accuses it of being “pretty silly” and having “some weak dialogue”. Richard Scheib at Moria Reviews gives First Man Into Space 2/5 stars, writing: “First Man Into Space shares many of the same problems that Fiend Without a Face does, namely a dull and uninteresting visual style and a pedestrian pace. It is probably marginally a better film than Fiend on some levels, although lacks such moments of schlock intensity as the hopping brains climax in Fiend.”

Others are slightly more positive. At Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings, Dave Sindelar writes: “The first half of this movie is a draggy bore; the conflicts between the main characters are cliched, and the director does nothing to make the exposition exciting or interesting. However, once we find ourselves dealing with a blood-thirsty monster in the second half, the movie perks up considerably”. Michael Lennick does a write-up for The Criterion Collection, which should perhaps be taken with a grain of salt, as this was a tie-in with the film’s 2007 Criterion DVD release. That being said, Lennick is positively gushing over the movie: “Given the inherent fantasy of its central story, First Man into Space actually hangs together quite well after all these years and so much history—a tribute to the foresight and talents of its producers, director, and cast. The film clips along at a sprightly pace, with nary a wasted shot or edit, delivering several nicely choreographed, and thus well-earned, shocks and some genuine pathos at its climax.”

The film’s inclusion in the Criterion Collection has raised the film’s status to something of a cult classic, which it simply isn’t.

Cast & Crew

Executive producer Richard Gordon was the brother of slightly better known Alex Gordon. The brothers both became interested in the movies from a young age, and relocated for greener pastures in New York in the 40s. Alex moved to Los Angeles, where he befriended people like Bela Lugosi and Ed Wood, and became one of the original producers of American International Pictures. Richard stayed in New York, where he set up his own company Gordon Films, importing and distributing British and international films to the US. He gradually became more interested film production, and ended up being the de facto producer on many films from the mid-50s onward, even if he was often uncredited for the first decade of his producing career. A friend of both horror and science fiction, he produced Escapement (1958, review), Fiend Without a Face (1958, review), First Man Into Space (1959), The Projected Man (1966), Island of Terror (1966), Horror Hospital (1973) and Inseminoid (1981).

Nominal producer on the film was John Croydon, a British production manager and producer who was active from the early 30s to the late 50s. He is best remembered today for his collaboration on the SF/horror films of Richard Gordon: Fiend Without a Face (1958, review), Haunted Strangler (1958), First Man Into Space (1959) and The Projected Man (1966), the latter three of which he also co-wrote the screenplays for.

Director Robert Day rose in the ranks of the British film industry, starting as a clapper boy and and ending up as a director. He directed his first movie at the age of 34 in 1956, and was still quite an unknown even in Britian when he started doing work for Richard Gordon and John Croydon. For them, he made the Boris Karloff vehicles The Haunted Strangler and Corridors of Blood, both in 1958, as well as First Man Into Space (1959). He made a bit of a name for himself with Two Way Stretch (1960), starring Peter Sellers, but didn’t quite make the leap to A-pictures. Instead he came to direct four Tarzan movies between 1963 and 1967, starring three different Tarzans. Tarzan the Magnificent (1960) was the last in the series starring Gordon Scott, Tarzan’s Three Challenges (1963) was one of two movies with Jock Mahoney as the king of the jungle, and Day also directed two of Mike Henry’s three ape man films: Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966) and Tarzan and the Great River (1967). These were all UK-USA co-productions. He also directed Hammer’s 1965 adaptation of H. Rider Haggard’s classic She.

Alongside his movie work, Robert Day also directed for television – in Britain he among other things directed several episodes of The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Avengers. He made the move to Hollywood in 1967, where he came to specialise in TV – he directed numerous TV movies and shows. He had quite a successful career, directing such hit shows as Kojak, Dallas and Matlock. His best known TV movie is the western The Quick and the Dead (1987). Of the two feature films he directed in the US, one is the US-Italian sci-fi MacGuffin film The Big Game (1973), not to be confused with Jalmari Helander’s Samuel L. Jackson vehicle Big Game (2014).

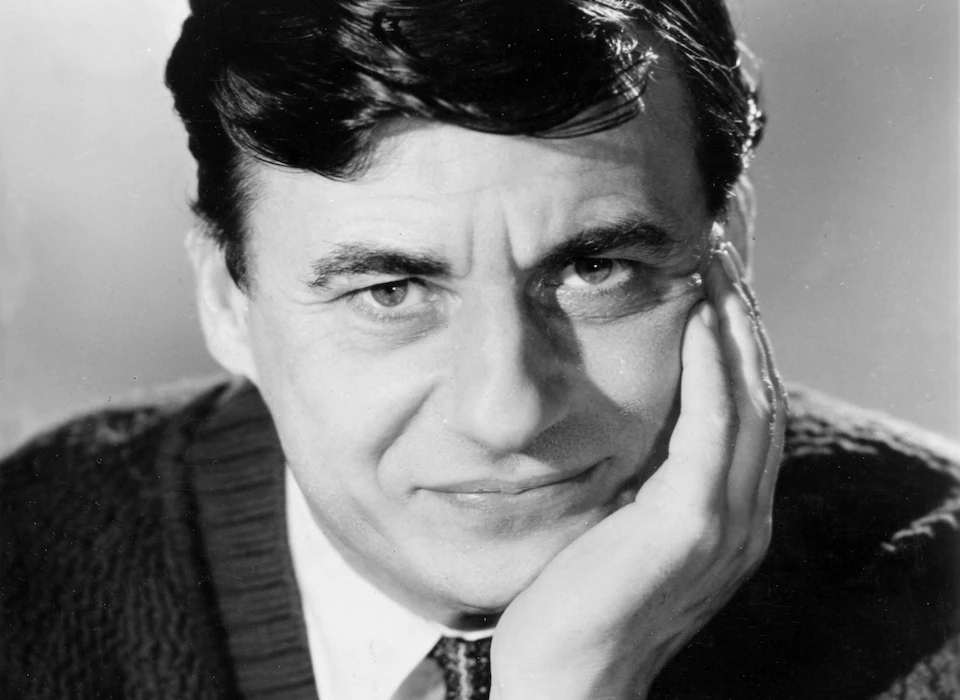

I have a long write-up on lead actor Marshall Thompson in my review of Fiend Without a Face, so head there for a more in-depth biography. In short, Thompson had a long and quite successful career, and was able to adapt and reform himself over the years, eventually combining his work in front of the camera with producing and directing. In the 50s he also racked up something of a science fiction legacy.

Marshall Thompson emerged as a boy-next-door in smaller roles the mid-40s, and worked his way up in “perfunctory nice-guy assignments” over the years at Universal and MGM, before he went freelance in 1950. In the mid-50s he did work of varying quality, including a few leads in B-movies, until he hit a peak in 1955 with leads in To Hell and Back, Battle Taxi and Cult of the Cobra. However, after this he found himself stuck mostly in minor pictures. This was when he became something of a science fiction staple, appearing in leading roles in It! The Terror from Beyond Space (1958, review), Fiend Without a Face (1958, review) and First Man into Space (1959). However, he bounced back in the mid-60s when his old friend Ivan Tors hired him as director on several episodes of the animal-themed hit TV series Flipper in 1965. The same year saw the release of Tors’ family movie Clarence the Cross-Eyed Lion, with Thompson in the lead, and made from a story treatment by Thompson. The following year Thompson appeared in another Tors film, the science fiction movie Around the World Under the Sea. However, more importantly, Thompson and Tors decided to create a TV series based on Clarence the Cross-Eyed Lion and the result was Daktari (1966-1969). The TV show became a surprise hit, ran for four seasons, and finally lifted Thompson into star status.

After the success of Daktari, Thompson worked mainly in TV, although he found time to appear in a handful of feature films, including the SF/horror film Bog (1979), an ultra-low-budget monster movie inspired by Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review). He only worked sporadically in the 80s, focusing more on providing nature and wildlife photography for TV, and made his last film apperance in 1991.

The titular role of First Man Into Space was played by Canadian-born expatBill Edwards, presumably hired mainly on the strength of his ability to do an American accent. He recorded all his dialogue in post-production, as he wasn’t able to keep up the accent on set. He appeared in around 20 films between 1957 and 1967, mostly in minor roles. He had small roles as a radar operator inBehemoth the Sea Monster (1959, review) and as an American astronaut in The Mouse on the Moon (1963). He had an uncredited role as a gangster in the classic James Bond spy-fiGoldfinger (1964).

Italian fashion model Marla Landi arrived in the UK in 1954 with her first husband, who was stationed in London for work. She immediately attracted the interest of the British movie scene, and was cast in the lead of half a dozen B-movies between 1955 and 1965, as well as a guest star in several TV shows. Her best known film role is that of Cecile, the femme fatale of Hammer’s excellent adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959), opposite Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. However, Brits of a certain age remember her best as the popular presenter of the children’s TV program Play Time (1964–1970). She quit the TV business in 1970 and became a fashion editor for Harper’s Bazaar, and later set up her own wig business.

Carl Jaffe was one of the many Germans that escaped the Nazis in the 30s and 40s to England, where he carved out a decent career as a supporting player. Jaffe had a tendency to show up as a doctor or scientist, as he did in Timeslip (1955, review), Satellite in the Sky (1956, review) Escapement (1958, review), First Man Into Space (1959) and Battle Beneath the Earth (1967).

Roger Delgado, here in a small but memorable role as a Mexican consul, was born to Spanish and French parents in the UK, and was often cast as villains on stage, screen and TV. He is best remembered for originating the role of the Doctor’s nemesis the Master in the long-running TV show Doctor Who. He played the character in 37 episodes between 1971 and 1973, and would probably have continued to do so, had he not died in a car accident while filming in Turkey in 1973.

Flo Nordhoff and Karl-Ludwig Ruppel created special effects for Richard Gordon’s science fiction movies Fiend Without a Face (1958, review) and First Man Into Space (1959), and Nordhoff also worked on Gordon’s The Projected Man (1966).

Editor Peter Mayhew is not to be confused with the other Peter Mayhew.

Janne Wass

First Man Into Space. 1959, USA/UK. Directed by Robert Day. Written by John Croydon, Charles Vetter, Wyott Ordung. Starring: Marshall Thompson, Marla Landi, Bill Edwards, Carl Jaffe, Robert Ayres, Bill Nagy, Roger Delgado. Music: Buxton Orr. Cinematography: Geoffrey Faithfull. Editing: Peter Mayhew. Art director: Denys Pavitt. Costume designer: Anna Selby-Walker. Makeup: Michael Morris. Special effects: Flo Nordhoff, Karl-Ludwig Ruppel. Produced by Richard Gordon, John Croydon, Charles Vetter for Amalgamated Productions & MGM.

Leave a reply to Janne Wass Cancel reply