An Oscar nominee for best picture, MGM:s 1950 adaptation of H. Rider Haggard’s adventure novel dazzled audiences with its Technicolor images of African wildlife and exotic natives. However, the film more closely resembles a nature documentary than a work of narrative cinema. (3/10)

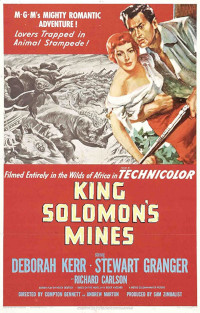

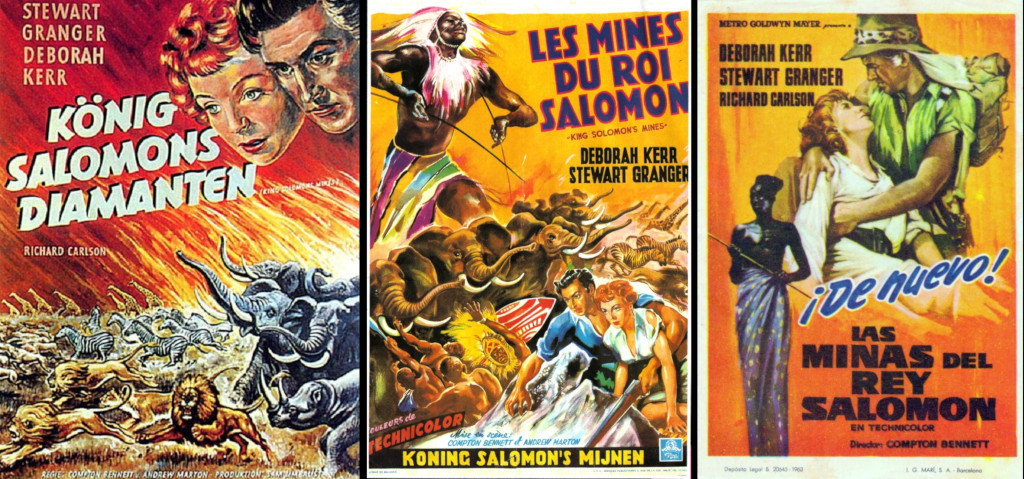

King Solomon’s Mines. 1950, USA. Directed by Compton Bennett & Andre Marton. Written by Helen Deutsch. Based on novel by H. Rider Haggard. Starring: Deborah Kerr, Stewart Granger, Richard Carlson, Hugo Haas, Kimursi, Siriaque, Lowell Gilmore. Produced by Sam Zimbalist. IMDb: 6.8/10. Rotten Tomatoes: 92/100. Metacritic: N/A.

It is a rare treat for me that I get to review an Oscar winner on this blog. It was therefore with much anticipation that I sat myself down to watch the 1950 big-budget MGM adaptation of H. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines. Not only did the film win the Academy Awards for best colour cinematography and editing, it was actually a best picture nominee for the 1951 Academy Awards. A huge undertaking, the film was shot almost entirely on location in Africa, in beautiful Technicolor, and stars big names like Stewart Granger and Deborah Kerr in the leads, along with one of my favourite actors, science fiction staple Richard Carlson. Unfortunately the film doesn’t quite live up to its pedigree. But more on that in a while, first a few words on the source novel.

King Solomons Mines, along with British author H. Rider Haggard’s follow-up She, is considered one of the most important early works in the lost world genre, written in 1885, before Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912) and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ At the Earth’s Core (1914). Both were central to the development of the SF subsgenre of the “secondary world”. As Victorian scholar Patrick Brantinger puts it: “Haggard may seem peripheral to the development of science fiction, and yet his African quest romances could easily be transposed to other planets and galaxies”.

The book tells the story of aged big game hunter and adventurer Allan Quatermain, who teams up with a group of comrades in search King Solomon’s mythical diamond mines in the heart of an unexplored region of Africa. Quatermain’s stated reason for the adventure is to help his new acquaintance Sir Henry Curtis find his brother, believed to have disappeared on a similar quest. He is joined by Henry’s friend Captain Good, and Quatermain’s loyal friend and tracker, the Hottentot Hans. The last companion on his trek is the mysterious Umbopa, a warrior of majestic stature who seems to know a lot more about King Solomon’s Mines than he lets on. After trekking through a deadly desert and traversing a near-impossible ring of mountains, they find a green country encircled by an impassable ring of rock. While bathing and shaving, Good is discovered by a group of natives who call themselves the Kukuana. Seeing his milky-white legs, his monocle and his half-shaven face, the Kukuana believe him a god, and the group is taken to see King Twala.

However, seeing Umpoba, the king’s witch doctor Gagool smells a rat, and orders that he be put to death as a “traitor”. It turns out that Umbopa is the rightful heir to the throne of Kukuanaland and thus a rival to the evil Twala. On the eve of Umbopa’s execution, the Englishmen are able to predict a solar eclipse (lunar eclipse in later editions), “proving” that they have the power to stand up to Gagool’s magic — and inciting a rebellion as a part of the Kukuana support Umbopa’s claim to the throne. The book then follows the civil war among he Kukuana, ending in victory for Umbopa. With Twala slain, Gagool reluctantly agrees to reveal the location of King Solomon’s Mines. However, in a last act of treachery, Gagool brings down the ceiling of the mine with her magic, trapping Good, Henry and Quatermain inside, making for a claustrophobic climax of the novel. Along the way there’s also some interracial romance, as Captain Good falls in love with a native girl, an emotional moment at the death of Quatermain’s friend and tracker Hans, and a battle of giants as Twala and Sir Henry go up against each other in hand-to-hand combat.

Haggard’s broadly drawn, engaging characters, his imaginative adventure, fast-paced action and the beautifully rendered description of Africa, drawn on first-hand knowledge, made Haggard and over-night sensation. Haggard, a missionary to Zululand, anthropologist and scholar of Zulu culture and history, had written a couple of unsuccessful novels and stories upon his return to England in 1882, and apparently the birth of King Solomon’s Mines came about when his brother wagered him that he “couldn’t write a novel half as good as Stevenson’s Treasure Island“. Haggard wrote the first draft over a period of four weeks, and made little revision later, apart from a number of footnotes and comments. He followed up the success of King Solomon’s Mines in 1886 with the even more successful and influential She, which established him as one of the most foremost adventure writers of his generation. He continued adding to the saga of both Allan Quatermain and She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed (Ayesha) into the early thirties with a number of novels of varying quality and originality. Few, if any, of these books surpass King Solomon’s Mines in terms of sheer sense of adventure and spectacle.

Unfortunately, King Solomon’s Mines and She both belong to the category of books that have been adapted for the screen numerous times, but never quite satisfactory. This does not mean that the adaptations are bad films as such, but most of them omit much of the original story that made the book so enjoyable in the first place. MGM’s 1950 adaptation if King Solomon’s Mines is the third, following a now lost 1918 South African film and a British 1937 black and white production, reviewed here. The 1937 version is considered by many to be the best, and I gave it an approving 6/10 rating in my review. After now watching the American 1950 version, I must also conclude that it is the British adaptation that sticks closest to the source novel. (The 1985 version is hardly worth mentioning, as it borrows precious little from the book except the title and the character names.) In 1937 British Gaumont sent its B-unit to Africa to shoot location footage and crowd scenes and used body doubles for the main characters. However, the principle cast of that film, including Cedric Hardwicke as Quatermain and American musical star Paul Robeson as Umbopa, never actually set foot in the continent. Here the 1950 MGM version does one better: Almost the entire film is shot in Africa, principle cast and all, and the films relies heavily on local talent for the supporting roles — greatly diminished though they are.

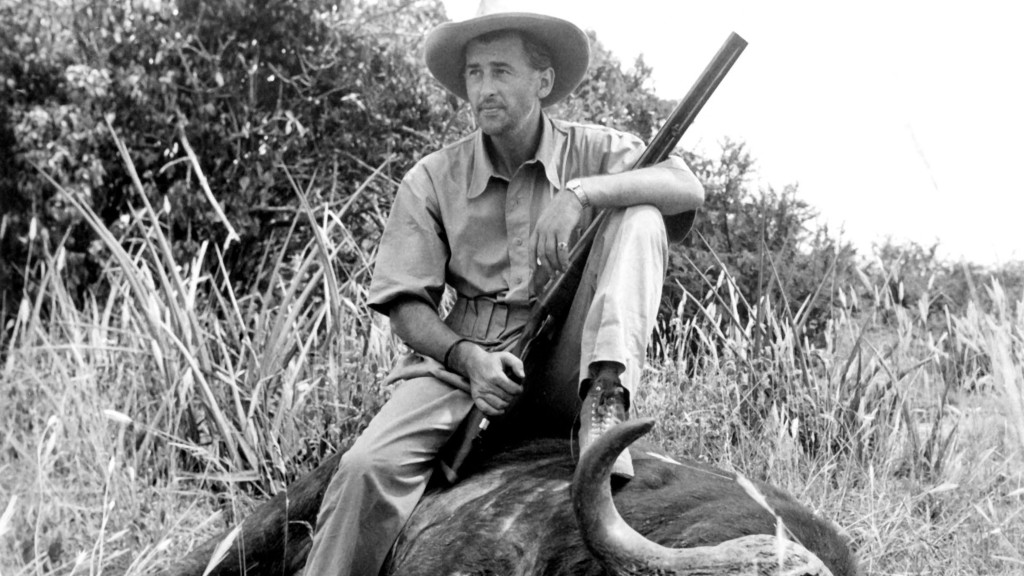

Plot-wise, the film hits many of the major beats of the book. We’re introduced to Allan Quatermaine (here, as in most adaptations, as QuaRtermain) in a newly written prologue in which the protagonist (Stewart Granger) immediately reveals himself to be a gruff big game hunter with a heart. Leading a group of rich British nitwits on an elephant hunt, he stops them from killing more than one elephant, and later pays his heartfelt respects to the widow of the African hunter who died on the expedition, protecting one of the Brits. In this scene, by the way, it is painfully obvious that the elephant is killed for real, a startling realisation for 21st century audience. While incredible to a modern audience, the elephant was put down as part of an environmental culling operation, as the area had too many elephants for the ecosystem to cope with.

Quatermain, as in the book, is ready to give up “the life” and return to Britain to look after his son, as he feels that roaming Africa is a bit “been there, done that and I did it before it was cool”. But he is persuaded to go on one last ridiculous adventure by Captain Good (Richard Carlson) and Sir Henry Cur … ahem, Mrs Henry Curtis, Elizabeth (Deborah Kerr), and, more importantly, by an astronomic sum of money.

The problem for movie producers adapting King Solomon’s Mines is that the fellowship of the mines doesn’t include a female character — well it actually does, but she arrives late to the party and she is black and in love with Captain Good, which just wasn’t appropriate either in Britain in the thirties or the States in the fifties. The British version got around this problem by simply adding one more member to the party. The US version instead turns the man-mountain Henry Curtis into the prissy love interest Elizabeth Curtis, who is on a mission to find her husband Henry, lost on a crazy quest to find King Solomon’s fabled mines. In this version, Captain Good is her brother. This isn’t something to take great offence over, as it was, naturally, unthinkable for any screenwriter to deliver a script for a big-budget adventure movie to the heads of a major studio without a white female lead. However, one does mourn the fact that in removing Sir Henry from the equation, one also removes the wonderfully undynamic duo of Good and Curtis from the story, which is one of the things that makes the book so enjoyable. And without the viking-like Henry Curtis as a counterpoint, there is no point in keeping Good’s prissy mannerisms, and screenwriter Helen Deutsch has also reduced Richard Carlson’s character to a wholly forgettable “moral support character”, or “audience stand-in” if you like.

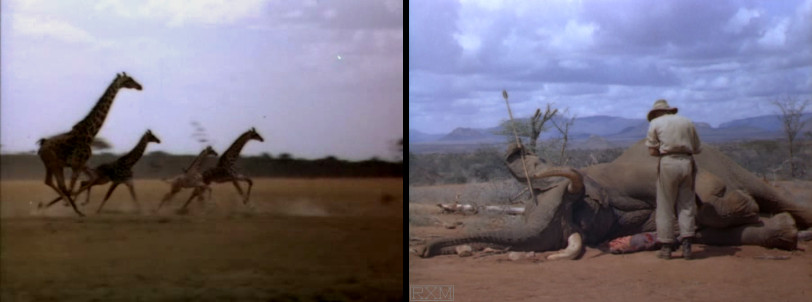

After the meeting between Mrs. Curtis and Quatermain, which tingles with both mutual contempt and sexual tension, the party sets out on a long — long! — trek through an ever-changing backdrop of jungle, savanna and rock desert, encountering along the way every conceivable species of wildlife that Africa has to offer. A dozen times the lives of the adventurers are in danger, and just as many times they are saved by the cunning and bravery of Allan Quatermain. At one point the group is caught in a massive stampede, with antelopes, zebras and giraffes wildly rushing past the party, threatening to trample them all underfoot. The sequence is perhaps a tad too stretched-out, but it is an awesome sight to behold — reportedly 6 000 animals were rounded up, all in all, to star in the movie, the majority of which are crammed into this scene. With the help of long lenses, some superb animal wrangling, very brave stuntmen and a little bit of special effects trickery, the sequence catches the viewer with their heart in their mouth.

Apart from the never-ending barrage of wildlife, the theme of the movie is the tension between Quatermain and Mrs. Curtis, a love/hate relationship in which the former, unsurprisingly, soon gets the upper hand. The romance develops at the same rate as Elizabeth sheds her corsets for more practical attire and lets her tough-as-nails attitude emerge. The final turning point is when she stops complaining about bugs in her long hair, and emerges from a bath in the wild with a perfectly coiffed Doris Day hairdo, for which Quatermain heartily complements her. Apparently the scene with Elizabeth emerging from the mountain pond with a glamour hairdo elicited roaring laughter at the previews, and the producers considered cutting it out. However, Deborah Kerr spends half of the film in this hairstyle, and they finally decided they needed a scene to explain why her hair is suddenly short, so they decided to keep it in, laughs or no laughs.

Aside from the afore-mentioned travellers, the party is rounded up by Allan’s trusted (something, it remains unclear what his actual function is) Khiva (Kimursi), a variation on the literary character of Hans, Quatermain’s friend and tracker, as well as a large retinue of bearers, who get scarcer by each danger they encounter. Apparently hiding behind a rock and waiting for the party to pass by is also the mysterious and tall Umbopa (Watusi local Siriaque), who offers to join the expedition and act as guide. Despite his suspicions, Quatermain accepts the offer. At one point the fellowship run into a group of natives (apparently Masai) harbouring a white criminal on the run (Hugo Haas), and during a chase through the jungle, Khiva is killed.

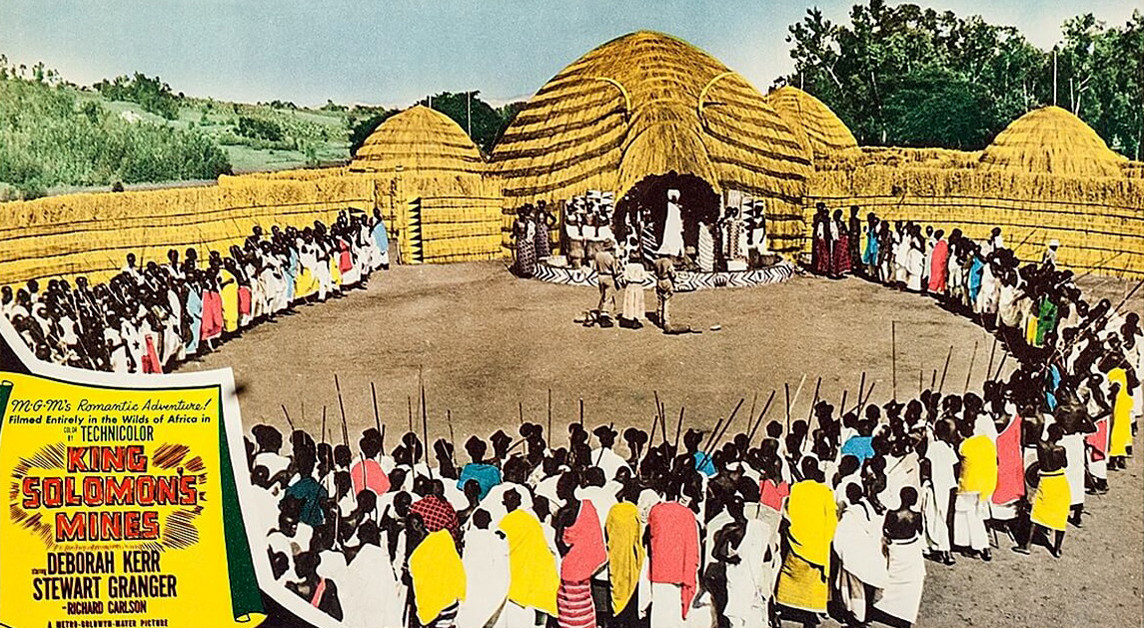

Around 75 minutes into the 100-minute-long film, the explorers finally arrive at the fabled desert, a scene which begins on page 43 in my 200-page long copy of the book. Ten minutes later our heroes encounter the lost Kukuana tribe (here played by the tall and slender Watusi/Tutsi people), which occurs in my book on page 54. As stated, the movie hits most of the major beats of the novel, which means there is now about 15 minutes time to introduce King Twala and his witch doctor, present the notion of the lost people, introduce Umbopa as the rightful king, build up to a civil war, find King Solomon’s mines, get the heroes trapped by Gagool and find their way out, and finally have Umpoba and Twala engage in a duel. Four of those minutes are taken up by a scene featuring a wholly pointless tribal dance. Which means that about 3/4 of the entire novel is here condensed into 11 minutes. Miraculously, the film pulls it off (omitting quite a few plot points along the way, of course).

The background of the film is that MGM at the time had a habit of making one or two big-budget overseas spectacles a year, and King Solomon’s Mines was slated for 1950. This choice might have had something to do with the fact that Warner had another African adventure, African Queen (1951), in the pipeline, also to be filmed on location. MGM had bought the film rights to the novel King Solomon’s Mines from Gaumont, who produced the British adaptation, in 1946, and in 1948 Helen Deutsch signed on as scriptwriter. Deutsch was not necessarily known for writing the sort of juvenile, swashbuckling adventure that Haggard represented, but rather for more adult-oriented romance adventures and family comedies, and the choice of screenwriter clearly shows how MGM envisioned the movie. The tagline on the poster read: “MGM’S MIGHTY ROMANTIC ADVENTURE! Lovers Trapped in Animal Stampede!” The budget of the film was a staggering 3.5 million dollars, which made it one of the most expensive movies ever made at the time. This also meant that King Solomon’s Mines could not only be marketed to the adventure-hungry juveniles that were the target audience for the original book, but had to appeal to a broad demographic, including adults of both sexes. While the fantastic and magical aspects of Haggard’s novel are more ambiguous and toned down in King Solomon’s Mines than in many of his other novels, they are still a central element in the creation of the sense of wonder in the original work — not least personified in the character of the “ancient” female witch doctor Gagool. But anything encroaching on the boundaries of magic and fantasy was at the time of the film’s making deemed as children’s fare, so Deutsch has meticulously cleansed the script of any and all fantastic content, which makes for a somewhat dry and dull retelling of the second half of the story. In the film Gagool is, for some reason, changed into a man (Sekaryongo), and barely even registers on screen, even though he/she is one of the central, and most memorable, characters of the book.

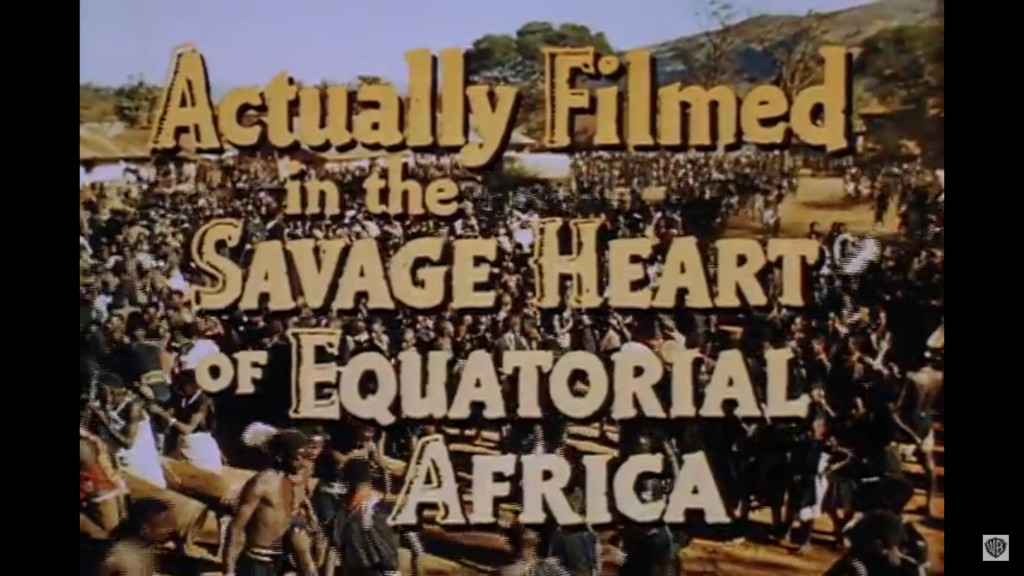

The movie is filmed in Technicolor — not a super-new technique in 1950, but still reserved mostly for major studios, and mainly for their high-profile projects. Three-strip Technicolor was an expensive, cumbersome and noisy process, requiring very large cameras filming three different strips of film at one time. Not only this, but the cameras had to be lugged around the African countryside on savannas, in jungles and on snow-covered mountains. The crew spent a full five months in Africa, shooting much of its wildlife which was then inserted into the picture, sometimes resulting in mis-matching biology, geography and background. Nevertheless, this was the first major Hollywood production to be shot primarily in Africa since 1937, and probably the first Technicolor movie to be filmed on the continent. The site Colonial Film writes: “With 95% of its footage filmed on location in Kenya, Uganda, Ruanda-Urundi, the Belgian Congo (today the Democratic Republic of Congo), and Tanganyika (today Tanzania), the film cost $3.5 million and required a monumental production team who enlisted 8000 Africans from twelve different tribes and 6000 animals, many of which needed to be organised by trainers to stampede. One historian has called it the ‘largest safari since Theodore Roosevelt’s’ (in 1909), including 53 Europeans and 130 Africans travelling by plane, steamboat, car, and foot”.

Of course, it was not only the local wildlife that held interest for audiences, but also the vivid colour photography of African tribes. There is a long scene involving Hugo Haas’ criminal who is hiding among a tribe that is not named in the film, but which was filmed with a large group of Masai extras in traditional body paint and clothing. Chiefly, though, it is the Watusi, which we today call the Tutsi, people who are featured in the movie, because of their tall and slender build, easily recalling something otherworldly if you put a whole group of their tallest members in one shot. It is no surprise then, that much of the film’s running time is filled up with tribal dances and shots of solemn, perhaps threatening-looking Africans looking into the camera lenses.

In essence, what MGM was offering audiences was an adventurous and romantic safari into darkest Africa, with stunning colour photography of animals, nature and peoples that had previously only been seen in still images or in black and white movie photography. The film also went out of its way to capture the traditional music of Africa, as well as genuine culture and tradition. The focus of the movie, thus, was to take the audience on a safari, and the actual story on which the film was based was pushed to the background.

From a commercial point of view, MGM played their cards right. King Solomon’s Mines was a huge success, becoming the studio’s top-grossing film of 1950, and the third most successful film in the US the same year. Its incredible on-location footage garnered it two Oscar wins and even lifted it up to a best picture nomination, which in hindsight is one of the more bizarre nominations in the history of the Academy Awards, as the movie is almost renons of any actual plot for over half of its running time, as we hop from one animal encounter to the next.

I have made several comparisons with the novel during this article, partly because it is one of my favourite novels, but also because I want to point out what it was in the novel that made it such a success, and a story which still captivates a reader today, despite its many dated notions. It is not that I frown upon films that use a work of literature as a starting point and then change the story up, for one or another reason. I do, however, dislike when a film uses a book as a starting point and then throws most of it out the window — unless, as in some rare cases, it does so purposely in order to make a point or comment upon the original work. King Solomon’s Mines is not one of those rare cases. As I have tried to point out above, MGM’s purpose seems not so much to have been to tell Haggard’s story, but rather to take the audience on an African safari in Technicolor. And this could have been a great story, had Helen Deutsch actually added any proper plot to the script. However, her job seems to have ended where filming begun, and the producers, directors and editors then hacked away as much of the plot as possible in order to make room for more animals and tribal dances. This means that for about an hour in this 100-minute film there is really no plot in play, other than Allan Quatermain introducing us to yet another animal that the production crew has stumbled over. Unless you count the inane romance between Quatermain and Mrs. Curtis as “plot”.

What I especially mourn is that the book is so rife with wonderful characters and moments that have all been cut out of the movie — for no apparent reason other than to minimise the amount of time taken away from animal footage. Allan Quatermain is actually the least interesting character in the books featuring him. The British filmmakers understood this, giving the spotlight to Umpoba and keeping the wonderful idiosyncrasies of Good and Henry intact. Here Henry is omitted and Good turned into a dullard. In a sense, Captain Good’s uptight behaviour and his penchant for cleanliness and manners have been transferred to the character of Elizabeth. However, it is far less funny when it is played out as “typical female behaviour” from a woman out of her element, than when it was attached to Captain Good, a seasoned military officer and a veteran of the African wild. And as stated earlier, when Elizabeth takes on the mannerisms of Captain Good, Richard Carlson, playing Good in the movie, is left with a character wholly bereft of personality. Deborah Kerr is a great actress and does the role as intended with panache, however idiotic it may be. Carlson gets little chance to show off his acting chops as Good, and doesn’t even attempt a British accent. He’s not necessarily miscast as much as wasted in the role.

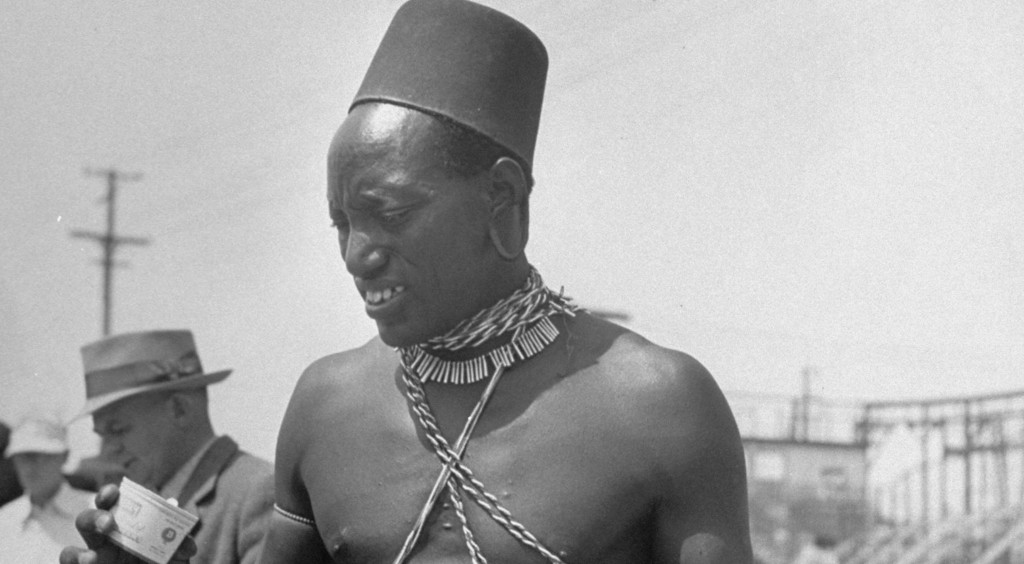

From one point of view one can applaud the fact that MGM used local talent for Umpoba, but unfortunately the talent in question, Siriaque, was no actor and spoke no English. Not only does this greatly reduce his screen time, but he also does a fairly poor job with what little material he has, and at no point in the film evokes the majesty and mystery — and wit — described in wonderful detail about the literary character. The same goes for the characters of Twala and Gagool. The African character from the book most accurately transferred to the screen is probably Khiva/Hans, played by a fellow called Kimursi, who actually does a pretty good job of capturing Hans’ dry wit and laid-back attitude. The actor seems to be proficient in English, which is probably why Khiva becomes the most heavily featured African of the film.

On the one hand, it was a bold move by MGM to fill a number of the central roles in the movie with African amateurs, even more so to give three of them room in the opening credits. This was almost unheard of in 1950, with Jim Crow laws still in effect in the US, and the civil rights movement still in its infancy. In King Solomon’s Mines, the African players were no longer just nameless and faceless savages posing as an exotic threat to the white protagonists, but were recognised as individual contributors to the movie. The character of Khiva is given a heroic death, which is emotionally mourned by Quatermain. Likewise, the cameras treat Umbopa with respect and the story even tries to make him seem majestic and awesome. The actor playing Khiva, Kimursi, was a police officer, which may account for his understanding of English, and he was even flown to Hollywood in order to do PR for the film (he was allegedly paid a bonus of eight cows).

On the other hand, despite the touch of reality that using African amateurs in the movie brings, it also poses the problem that none of these players were trained actors, and most of them couldn’t speak any English. So despite that legendary film critic Pauline Kael wrote at the time that “the Africans take all the acting honors”, it’s a serious problem for the film that a number of its central characters can’t act themselves out of a paper bag.

There’s a lot that can be said about what place King Solomon’s Mines hold in the history of Hollywood cinema when it comes to challenging the stereotypes of Africa and in the treatment of the African characters in the film. On the one hand, it is far more progressive than probably any big-budget Hollywood movie set in Africa at the time. On the other hand, it pales considerably when compared to Haggard’s novel, written during the height of imperialism over sixty years prior. And while the film itself treats its African characters with respect, the whole purpose of the movie is to give US and European audiences a piece of lurid exotism, a chance to glimpse the dangerous wildlife and the primitive African tribes in spectacular Technicolor. But for more on these issues, please read the brilliant article on the subject at Colonial Film.

From a purely cinematic perspective, King Solomon’s Mines is wildly uneven. There is no arguing that the images of nature, wildlife and African tribal culture earned cinematographer Robert Surtees a well-deserved Academy Award. The setups, subtle visual effects and superb editing in the stampede scene make it a standout sequence in movie history. But alongside some of these beautifully filmed and edited scenes, just as many stand out as sore thumbs because they seem flat, uninspired, unrehearsed and downright clumsy. There is almost no finesse in any of the character footage and especially scenes in which the lead actors interact with large groups of African extras or animals have the feel of being hastily shot, often from uninteresting angles and setups. One can imagine there were considerable problems getting a group consisting of up to a hundred extras or more, poorly paid, unaccustomed to filmmaking, unfamiliar with the English language, and to some extent even hostile toward the cast and crew, to all take direction at the same time. And when everyone were lined up and quiet, the director probably just rushed through all the dialogue in order to get it all in the can before the situation unravelled. One of these scenes, unfortunately, is the final climax of the movie, where King Twala and Umpoba go up against each other in a spear duel. Here we have the two tall, gangly, fellows with no experience in acting, stunt work, fight choreography or anything else relevant to the task, going up against each other. Furthermore, none of them probably understood any English, so in all probability, the scene had to be directed through at least one interpreter. Plus, there is a whole tribe of Watusis behind them, threatening to break formation any minute, so director Andrew Marton and DP Surtees probably have no time to do multiple takes or play with camera setups. The end result is staged, flat and anticlimactic.

The initial director of King Solomon’s Mines was Brit Compton Bennett, who had previously worked for Alexander Korda’s production company London Films. His feature debut was the well-received The Seventh Veil (1945), which caught the eye of MGM, who brought him to Hollywood. After a few minor movies for the studio, King Solomon’s Mines was supposed to be his big break-out movie. However, the soft-spoken and somewhat inexperienced director didn’t get along with Stewart Granger, who apparently thought that Bennett wasn’t quite where it’s at, and he was fired fairly early on in the production. He was replaced by Andrew Marton, a Hungarian with a fierce reputation, especially as an assistant director specialised in big crowd and action scenes. Today he is probably best known for directing the famous chariot race scene in Ben-Hur (1959). The stampede scene in King Solomon’s Mines has his fingerprints all over it. Marton and Granger got on like a house on fire.

The film received largely positive reviews after its premiere. Variety wrote: “King Solomon’s Mines has been filmed against an authentic African background, lending an extremely realistic air to the H. Rider Haggard classic novel of a dangerous safari and discovery of a legendary mine full of King Solomon’s treasure.” Harrison’s Reports called it “a highly spectacular romantic adventure melodrama that has the rare quality of holding an audience captivated from start to finish.” And John McCarten of The New Yorker wrote, “King Solomon’s Mines undertakes to show what a safari through Africa might have been up against fifty years ago. In this, I think, the picture, which was shot in the African highlands, succeeds admirably.” However, some critics looked beyond the striking wildlife photography wowing the audiences. For example, The Monthly Film Bulletin called King Solomon’s Mines “a somewhat stilted epic, strangely lacking in excitement”. Bosley Crowther of the New York Times did praise the film’s “scenic novelty and beauty”, and wrote that “the genuine assets of the game-crowded African veld, of picturesque native villages and of the rugged, magnificent countryside have been so utilized in producing this picture’s well-calculated thrills that it is hard to apportion precisely the phoney and the real”. However, he also noted that “the elemental story of a safari going into the African wilds in quest of a lost explorer who had gone searching for a fabled diamond mine is as lurid and artificial as any low-budget Tarzan tale, and the romance that blossoms on the journey between the guide and an English lady is just as pat”. Crowther noted that at heart it is an “adventure story that is loaded with standard perils and thrills”.

As mentioned repeatedly, King Solomon’s Mines certainly deserved its Oscar wins for cinematography and editing, but in hindsight it is one of the odder best picture nominations in the history of the Academy Awards. That’s not just me talking — the film received no other accolades that year. It wasn’t even nominated for best picture in any of the other big award ceremonies in 1951, not the Golden Globes, the Director’s Guild of America Awards, the National Board of Review Awards, nor the New York Film Critics Circle Awards.

Still a lot of modern critics hold the film in high regard, wowed by its photography of Africa and its wildlife. It has a decent 6.8/10 audience score on IMDb and a staggering 92/100 rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Both TV Guide and AllMovie give it 4/5 stars. While Richard Gilliam at AllMovie notes that the acting is standard and the chemistry between the romantic couple minimal, he writes: ” What works well are Robert Surtees’s superb cinematography and the outstanding editing of Conrad Nervig and Ralph Winters.” TV Guide also notes the somewhat stale story and wooden acting, but calls King Solomon’s Mines “one of the most majestically filmed adventure tales ever put on celluloid”.

Andy Webb at British The Movie Scene gives the film 4/5 stars, as does Derek Winnert. Webb praises “the excitement of a trek through a foreign country” and the “brilliant nature footage”, and writes that “in many ways it feels like a nature movie”. Winnert, on his part, lauds the “lively acting”, “sprightly direction” and “spectacular adventure”. Another 4/5 star review comes from French L’Oeil sur l’écran, which states: “The images in Technicolor are superb and often impressive, skillfully mixing the almost documentary aspect of the numerous shots of wild animals with the history of this expedition full of adventures and dangers.”According to the site, the film “has not lost its magic, thanks to its subtle blend of adventure and exoticism, even if may seem clichéd today”.

Interestingly enough, even those willing to admit the obvious narrative shortcomings of King Solomon’s Mines insist on giving high marks. Steven D. Graydanus from the National Catholic Register gives the film 3/4 on the site Decent Films, even while stating: “In the end, if King Solomon’s Mines doesn’t quite fulfill its promise, that’s in part because the title destination is too obviously a MacGuffin, a mere plot device in which the film ultimately doesn’t even feign mild interest. [D]irectors Compton Bennett and Andrew Marton are so eager to get back to Umbopa and his nemesis Twala that they can’t be bothered with the awe and dread of the mines themselves. It’s a miscalculation from which the film can’t really recover.”

While I admit that the quality of a film is often a matter of taste, I still find it puzzling that many reviewers and sites who often write sharp and insightful analyses of story and film composition manage to overlook the fact that for over half of its running time, King Solomon’s Mines is not a narrative film at all, but a potpourri of wildlife footage. Yes, it would be great if David Attenborough narrated it, but it’s a lousy excuse for a 3.5 million dollar adventure film, and it’s certainly not King Solomon’s Mines. Haggard himself loved to insert encounters with dangerous animals into his novels, but he had the wisdom to narrow these down to one or two per book. And when recognised that the film is rather plodding and narratively scant, it is often brushed under the carpet with statements like: [it is] “probably not going to work for those who watch it having watched more recent ‘Indiana Jones’ style versions” (from Andy Webb) or that it “might seem a bit tame to a generation raised on spectacular special effects, lighting fast editing and the irreverent fantasies of Raiders of the Lost Arc [sic]” (from Carter B. Horsley at The City Review). Not only is this condescending, but also misses the point that the 1950 adaptation of King Solomon’s Mines is, first and foremost, a special effects movie. But it’s not explosions or CGI critters that make up the effects, but the Technicolor footage of Africa. This was what audiences went to see, and this is what is now being touted as “real filmmaking” and “classic old-school cinema”. But what it all boils down to is that MGM has filled the movie with special effects without paying much attention to characters, narrative or story development. When critics now give 4-star reviews based on the nature footage of King Solomon’s Mines, it’s no different than giving 4-star reviews to the Transformer films based on the CGI. Just because it was made in the fifties doesn’t forgive it for riding on an effects gimmick. Yes, it’s great footage, but how does it all stack up as a film?

I suspect that the lack of critical perspective can be summed up by this sentence by Carter B. Horsley: “it was my favourite movie”. This is a film that a lot of critics grew up watching on TV as kids, and it was probably a film that their parents had seen and liked when premiered in the cinema. It is a “serious” melodrama spectacle and it’s got that Oscar pedigree, which makes it a “classic”, so it isn’t as easily dismissed as a low-budget genre film would be.

However, not everyone is awed by the movie. Charles T. Tatum gives it a decent 3/5 star review, writing: “The film is credited to two directors, since one apparently left the production midway through, but there is no noticeable change in the shooting style. Being on location, with hundreds of extras and wild animals, there really is no style onscreen at all. The camera set-ups are standard, as if they hurried to get a shot before anything could go wrong. The cast is good, but it’s hard to steal scenes from an entire continent.” Gene Phillips at Naturalistic Uncanny Marvellous notes that the film’s only real concern is the “banal ‘will-they-won’t-they’” between Quatermain and Mrs. Curtis. The Ace Black Blog, giving it 3/5 stars also, writes: “King Solomon’s Mines conveys the sweaty beauty of Africa, but fades into a safari trip postcard with a bit of plot on the margins of the pretty pictures.” Erik Beck notes: “It’s a documentary – one of those Disney nature films about the wilds of Africa. […] It’s mostly just an excuse to film a lot of Africa that had never been on screen before. And it looks wonderful. But to nominate it for Best Picture? That’s going a bit too far.” Lisa Marie Bowman at Through the Shattered Lens is likewise dumbfounded by King Solomon’s Mines’ best picture nomination: “It’s true that the film has a plot but, for the most part, it’s a travelogue. One gets the feeling that it was mostly sold as a chance for American and European audiences to see a part of the world that, up until that point, they had only read about.” Danish Tobies Lynge Herler writes at Philm.dk: “This is also the biggest weakness of the movie: As stated, it takes us through and over jungle and desert, but, then again, not much else happens in it”.

King Solomon’s Mines has been cited as a huge influence on later adventure movies, not least the work of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. But as Graydanus writes: “It is here, more than in the wall-to-wall excitement, that Raiders of the Lost Ark decisively surpasses its forerunner. Not first of all because Indiana Jones clings to the underside of a Nazi truck (although that’s good too), nor because Harrison Ford has far more appeal than Granger (though he does), but because in the end Steven Spielberg knows what to do with the ark of the covenant while Bennett and Marton don’t know what to do with King Solomon’s mines, King Solomon’s Mines, though enjoyable, falls short of the film it helped inspire.”

I don’t hate King Solomon’s Mines. It’s a (sometimes) beautifully shot, (sometimes) entertaining and (sometimes) quite funny adventure yarn with a classic Hollywood feel. The performances are, on the whole, decent. The images of East Africa are nice. But if you disregard the zoological parade and the tribal dances, it just feels like a flat, uninspired and rushed by-the-numbers retelling of the original story. Nobody in the production team seems to have had any particular interest in bringing Haggard’s work to life, as all sequences that actually have anything to do with the novel are told without much enthusiasm. And unfortunately Helen Deutsch’s own additions are dull and routine.

Deborah Kerr, of course, is one of the true legends of the screen, a six-time Oscar nominee and honorary award winner, probably best remembered for her work in From Here to Eternity (1953) and The King and I (1956). Kerr got the part as Elizabeth Curtis when she asked MGM brass for the lead in The African Queen, unaware that the film was going to be backed by United Artists. Of course, the role memorably went to Katherine Hepburn. But MGM told Kerr they had another lead lined up in another big-budget production that was also going to be filmed in Africa, and Kerr took the bait. Deborah Kerr did not do any other science fiction related films, but genre fans may have spotted her in the horror films The Innocents (1961) and Eye of the Devil (1967).

Stewart Granger is not often remembered today in discussions of old Hollywood legends, but there was a period in the early nineties when this British macho man was slated as the heir apparent to Errol Flynn. In fact, Flynn was tentatively attached to play Allan Quatermaine (as Haggard turned in his grave), but ultimately chose to instead star in the movie Kim (1950), another MGM Technicolor adventure, filmed in India. Apparently, the reason Flynn went with the Indian movie was that while filming Kim he would be allowed to stay at a resort, rather than roughing it in the African wild. And while I love Flynn, he would have been a really odd choice for Quatermain. Like Deborah Kerr, Granger had a solid background on the British stage and was likewise a star player in British cinema in the forties. Hollywood called in 1949 and King Solomon’s Mines was his first picture for MGM. His good looks and gruff macho demeanor paired with a snide smile made him a swashbuckling star of films like The Prisoner of Zenda and Scaramouche (both 1952), but Granger was displeased with his typecasting in flat romantic leads, something which had followed him from his career in Britain, where fellow Hollywood immigrant James Mason had always snatched the meatier roles at Gainsborough Pictures.

While Deborah Kerr dropped out of action in the late sixties, appalled at the sex and violence of modern movies, Stewart Granger divorced movie star Jean Simmons in 1960 and spent much of the sixties making movies in continental Europe. Largely forgotten by the broad audience upon his return to the US, he continued his stage work in New York, and spent much of the seventies and eighties doing guest spots on TV shows.

Richard Carlson is probably well-known to most readers of this blog, and I’ll get back to him in a later post. Suffice to say, King Solomon’s Mines was his first outing in a film with an SF connection, and it would still be a couple of years before he became a genre staple in films like The Magnetic Monster (1953, review), It Came from Outer Space (1953, review), The Maze (1953, review), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, review), Riders to the Stars (1954, review), The Power (1968) and The Valley of Gwangi (1969). As stated, Carlson is underused in King Solomon’s Mines. He turns in a solid performance, but his role is just completely redundant.

Hugo Haas, playing the escaped criminal, is primarily remembered today as a producer and director of a good dozen cheap potboiler melodramas in the fifties, with lewd titles like Pickup, One Girl’s Confession and Bait. But before that he was a respected writer, actor and director in his home country of Czechoslovakia, both on stage and in film. He both directed and played the lead in the flawed but very interesting Karel Capek adaptation Skeleton on Horseback (1937, review), a thinly veiled dystopian satire on Nazi Germany.

Haas fled to the US with the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia, and after spending the war years learning the language and building up his network with odd jobs, he achieved reasonable success as a respected character actor in a number of decent Hollywood movies, often playing somewhat flamboyant foreign villains. His role in King Solomon’s Mines was probably his most memorable one. As a director Haas earned the nickname of “the Czech Ed Wood“, which has later been interpreted as a comment on the quality of his films, which would seem somewhat uncalled for. But I suspect that this is later misunderstanding. Ed Wood’s reputation as “the worst director in history” is a rather modern one. At the time that Wood made his films they were generally viewed as bad, but not worse than a lot of the other Poverty Row productions made at the time. Rather, what set Ed Wood apart was that he was passionate about his bad movies, and styled himself an Orson Welles who would be involved in every aspect of the production: writing, producing, directing and often starring. This is what Wood and Haas had in common. According to his IMDb bio, Haas would take “total creative control with almost a Svengali-like obsession” over his so-called “vanity projects” that were “badly acted and obviously cheap and cheesy in production values”: While Haas’ films were critically panned, they were often moderately successful at the box office.

As one of the British safari members in the very beginning of Solomon’s Mines we see John Banner, who would later go on to TV immortality for playing Luftwaffe POW camp guard Sergeant Schultz in nearly 170 episodes of Hogan’s Heroes (1965–1971). He also had a number of guest appearances on the TV show Rocky Jones, Space Ranger in 1954.

As I mentioned in my previous reviews of films based on H. Rider Haggard’s work, I can understand why someone might question the validity of featuring Haggard on a blog devoted to science fiction movies. And I wouldn’t really go as far as claiming that even the novel King Solomon’s Mines is all-out science fiction. However, it is difficult to accept films like The Lost World (1925, review) and King Kong (1933, review) as SF without paying tribute to Haggard. Both films feature adventurers travelling to an unexplored region of the Earth, where they happen upon a lost world, isolated and untouched by time and civilisation, inhabited by creatures thought to belong only to fairy-tales. In the case of said films these creatures are dinosaurs and giant apes, and in King Solomon’s Mines it’s a lost African tribe and an evil witch doctor, but the principle is the same. That said, there is little in the 1950 adaptation of interest to the SF buff.

Janne Wass

King Solomon’s Mines. 1950, USA. Directed by Compton Bennett & Andre Marton. Written by Helen Deutsch. Based on the novel King Solomon’s Mines by H. Rider Haggard. Starring: Deborah Kerr, Stewart Granger, Richard Carlson, Hugo Haas, Kimursi, Siriaque, Sekaryongo, Baziga, Lowell Gilmore, Munto Anampio, John Banner, Benempinga, Gutare, Ivargwema, Henry Rowland. Music: Mischa Spoliansky, Cinematography: Robert Surtees. Editing: Conrad Nervig, Ralph Winters. Art direction: Cedric Gibbons, Paul Groesse. Costume design: Walter Plunkett. Recording supervisor: Douglas Shearer. Produced by Sam Zimbalist for MGM.

Leave a comment