Professor Quatermass investigates alien body snatchers that have secretly taken over the British government in this 1957 sequel. The script is original but sprawling, and lacks the original’s claustrophobic horror 6/10.

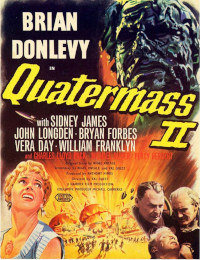

Quatermass 2. 1957, UK. Directed by Val Guest. Written by Nigel Kneale & Val Guest. Starring: Brian Donlevy, John Longden, Sidney James, Bryan Forbes, Tom Chatto, Vera Day. Produced by Anthony Hinds. IMDb: 6.8/10. Letterboxd: 3.3/5. Rotten Tomatoes: 6.5/10. Metacritic: N/A.

Professor Bernard Quatermass (Brian Donlevy) is in a bad mood. The government has decided to scrap his project for a colony on the moon. But his attention is soon diverted. Small, strange objects are falling from the sky around Winnerdon Flats. Professor Qatermass and his assistant Marsh (Bryan Forbes) investigate and find Winnerdon flats off-limits to the public, by goverment creed. Proceeding anyway, they discover dozens of small rocket-shaped objects near a huge facility which looks exactly like Quatermass’ plans for the lunar colony, only built at Winnerdon Flats. One of the objects cracks open and spews gas over Marsh, leaving him with a distinctive scar on his face. Immediately a team of armed guards with gas masks arrive and take Mars away, sending Quatermass packing.

So opens Hammer Films’ 1957 Quatermass 2, the first official sequel to the studios hugely successful horror/SF movie The Quatermass Xperiment (1955, review), based on Nigel Kneale’s BBC TV series Quatermass II (1955). Val Guest returns to the director’s chair, and American guest star Brian Donlevy is also back as the grumpy but effecient Professor Bernard Quatermass.

Along with Inspector Lomax (John Longden) and a nosy government MP who wants to uncover the truth about the top-secret facility (purporteldy manufacturing synthetic food), Vincent Broadhead (Tom Chatto) and reporter Jimmy Hall (Sidney James). Quatermass sets out to investigate what turns out to be a conspiracy reaching the highest levels of administration. The gas contained in the meteor-like objects is an alien life form, which is unable to live in Earth’s atmosphere, and uses humans as vessels, taking over their minds and creating an army of zombies. When invited to an official “inspection”, Quatermass and Broadhead realise they are about to be gassed. Quatermass escapes, but Broadhead perishes while investigating one of the huge metal domes at the facility, which turns out to contain a black goo, in essence a hive mind of millions of tiny alien life forms. The aliens have used Quatermass’ model of a lunar colony as a starting point to colonise Earth, rather than the other way around, and are now in the process of acclimatising themselves to Earth’s atmosphere.

In the vicinity of the facility, a small village of construction workers has been built to house guest workers unwittingly helping the aliens build their colony. They are initially hostile towards the nosy investigators, but when a “meterorite” falls through the roof of their community hall and infects a barmaid (Vera Day), and a team of guards armed with machine guns shoots hall dead for reporting to his newspaper by phone, they march upon the facility, where the film’s showdown takes place.

Background & Analysis

In 1953 writer Nigel Kneale created British TV history with his live broadcast TV series The Quatermass Experiment (review) — a groundbreaking science fiction series about an alien life form returning to Earth within the body of an astronaut, who slowly mutates into a giant blob that theatens to spread its spores all over London. It was without challenge the most popular TV show in British history, and the final episode almost eclipsed the audience numbers of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, which was held the same year. Hammer Films, which often bought BBC teleplays and TV shows and used them as basis for their films, snatched up the movie rights to the series, and set about adapting it into more of a horror film than a strict science fiction show. Because of their clause with US distributor Lippert Pictures that films intended for a US release had to feature a well-known American actor, slumming star Brian Donlevy was shipped to London, corset and whisky bottle in tow. The dark, tense and atmospheric SF/horror thriller was given an X rating by the British censors, usually a dreaded verdict, but one which Hammer shrewdly relished in, even slapping it into the title of the film, The Quatermass Xperiment (1955). Like the TV show, the film was a major hit, and made waves even in the US. A sequel was planned for 1956, but Nigel Kneale forbade Hammer from using the name Quatermass, as he wasn’t allowed by the BBC to participate in the writing process with a rivalling company. So Hammer changed the name of the lead character and the title to X the Unknown (review) and brought in Dean Jagger to play the “Quatermass” role instead. The film was successful, but without the Quatermass name, it didn’t quite have the same impact as the original. ‘

In 1955 Kneale made a second Quatermass TV series, Quatermass II, and in 1957 was given special permission by the BBC to adapt his teleplay into a script for Hammer. The director of the original film, Val Guest, was once again brought in, and took on the task of editing and re-writing Kneale’s script. The plot of the TV series remained largely intact, but Guest said on a DVD commentary, it had “lots of philosophising and very down-to-earth thinking but it was too long, it would not have held screenwise. So, again, I had to tailor it and sharpen it and hopefully not ruin it.” The main change is that in the climax of the series, Quatermass flies a rocket toward the alien “mothership” — in the film, it is Quatermass’ assistant Marsh (Bryan Forbes) who shoots an unmanned rocket toward the ship. The film also omits certain characters from the TV show and brings back some characters from the first film, which do not appear in the show (notably Inspector Lomax).

The budget for Quatermass 2 was considerably larger than that for the original film, close to £100,000 or around $400,000. This allowed for a great deal more location shooting. Hammer was given permission by oil company Shell to film at the Shell Haven refinery in Essex, standing in for the aliens’ base. Despite being a large facility, it was operated by a small crew, which made it easy for Guest to make the place feel empty and deserted. Guest also says he was surprised at how lax the management was about letting him stage a large-scale gunfight at the refinery. However, in some locales, a clockwork camera had to be used instead of an electric one, because of the risk of sparks. The steel domes that play a crucial role for the plot weren’t part of the actual refinery, but were added as matte elements by matte painter Les Bowie. A miniature model of the alien base was also used, in particular for the final scene in which the base is set on fire and the giant slime creatures erupt from the domes. The miniature work is fairly good. For the so-called “new town” built on-site for the construction workers, a real “new town” in Hertfordshire, which was under construction, was used. Some scenes were still filmed at the home of Hammer in Bray Studios, and some at the New Elstree Studios.

Quatermass 2 definitely feels more open and wide than the original film. This has pros and cons. The location shooting gives the movie an almost documentary feel, something which is enhanced by Guest’s and cinematographer Gerald Gibbs’ employment of cinéma vérité techniques, such as shaky camera an overlapping dialogue. The Shell location lends the movie both a grand and alien quality — it’s a worthy substitute for the legendary use of Westminster Abbey as a location in the original TV series. On the other hand, the film loses some of the claustrophobic atmosphere and sweaty pressure-cooker feeling that the first movie excelled in. Gibbs makes extensive use of day-for-night photography during the final act of the film, and it is not always convincing. The use of shaky cam also clashes with the movie’s otherwise rather conventional cinematography, and while sometimes effective, is also somewhat jarring. Neither am I convinced by the giant slime creatures at the end, especially when they are shown in “full figure” in the miniature shot. They look a bit too much like sock puppets covered in texture.

Once again, Nigel Kneale was unhappy with the casting of Brian Donlevy as Quatermass. You can’t really blame him — in the TV series Reginald Tate played him as an intelligent and refined, if driven, character. Brian Donlevy feels as if he has stepped right out of a hard-boiled detective noir. The problem is that Kneale insisted on writing Quatermass as the Tate character, when Hammer had created a distinctively different Quatermass for their first movie. Here, when Kneale is given more script input, the two characters clash. Donlevy has difficulties with the character in the beginning of the film, when he is prone to emotional outbursts and a sort of openness wholly incompatible with the Hammer Quatermass. As the story progresses, the Hammer Quatermass takes the front seat, and Donlevy’s performance improves along the way. In a biography by Andy Murray, Kneale says that he visited the set one day and that Donlevy was so drunk he could hardly stand up or read his lines from the cue card. However, in an interview with film historian Tom Weaver, Val Guest refutes these claims: “So many stories have been concocted since, about how he was a paralytic. It’s absolute balls, because he was not paralytic. He wasn’t stone cold sober either, but he was a pro and he knew his lines”. Donlevy clearly isn’t very agile when moving up and down stairs and feels very stiff throughout both Quatermass films. But this may partly be down to the fact that he was wearing a corset in order to slim down, and the fact that he was nearing 60 and perhaps not in the best physical shape. Plus some whisky, with which he laced the coffee that the crew fed him in their efforts to sober him up.

In the Weaver interview, Val Guest says he feels sad that Nigel Kneale ended up disliking all the film adaptations of his work. According to Guest, it may be because of hurt feelings because screenwriters and directors made changes to his original script drafts, and he didn’t get sole credit or the scripts just like he wanted; “A brilliant writer, but one whe writes stuff as though you were reading it in a book. […] So you have to make it a little more concise. […] But I really, honestly am sad about the situation with Nigel. He’s a brilliant guy and he’s had enormous success with all of these things – and he hates every minute of them.”

In the interview Guest also tells Weaver he agreed to make the first Quatermass film if he got to make it his way, with a documentary style, as if the things happening in the film were really happening, and someone told him to just grab a camera and go and document the story as it unfolded. The same thing is obviously true, maybe to an even greater extent, with Quatermass 2. Guest says that many people feel that Quatermass 2 was the best of the Quatermass films. Not Guest himself, however, who was “very disappointed” with the movie: “I didn’t think it was a patch on the first one, because the first one had a freshness. Quatermass 2, I felt, was reaching, somehow or other. But, it was very successful.”

I agree with Guest. There is a freshness in The Quatermass Xperiment that is lacking in Quatermass 2, a feeling that you are watching something extraordinary taking place in film history. Quatermass 2 also lacks the claustrophibic atmosphere and the sheer breathless energy of the first movie. Much of it comes from the fact that instead of a giant conspiracy, we have a much more personal invasion, an invasion taking place inside the body and the mind of a central characters – mysterious and wordless. The body horror of The Quatermass Xperiment makes it a predecessor of the films by David Cronenberg and his nightmarish visions. Quatermass 2, instead, labours with similar ideas as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, review), but not nearly as well as that film. Well, in a sense, Invasion also has a Cronenbergian feel and theme to it, which the second Quatermass film fails to capture – perhaps because all the infected people are side characters and are treated as cannon fodder, more than anything else. The possessed are merely faceless zombies for which you care little, and in whose presence you spend very little time. The horror here is cerebral, rather than visceral, which is something that divides modern critics.

Nevertheless, Quatermass 2 is a perfectly fine science fiction thriller, and it definitely has its moments. Guest’s direction is solid, and in parts, the films reaches a creepy, paranoid atmosphere. And as film scholar Bill Warren writes in his book Keep Watching the Skies!, Nigel Kneale’s strength was his “incredibly inventive, intelligently original storylines”. One should remember that Kneale’s original TV series aired before Invasion of the Body Snatchers came out in the US. When other films dealing with similar themes (the few that had been produced) dealt with local incidents, the beginnings of an invasion, in Quatermass 2, the protagonists realise that they are, in a sense, already too late – the aliens have already taken over the government. This was something novel on screen, and since I am at the moment reading Robert Heinlein’s 1951 novel The Puppet Masters, I can’t refrain from making a connection. As Kneale was obviously well-versed in literary SF, it’s not impossible he was inspired by the book.

Like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Quatermass 2 comments the cold war paranoia of the 50’s in a manner that can be interpreted in a number of ways. The aliens, of course, can be seen as communists infiltrating Britain. Post-WWII, Britain had been somewhat left-leaning, and had not taken on such drastic anti-communist measures as the US. The way the aliens easily infiltrate government may well be meant as a comment on England’s lax attitude toward the threat of communism. This is a view supported by film critic Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant, among others. But on the other hand, Britain at the time was ruled by a Conservative government whose almost draconian secrecy measures were strongly criticised by liberal and left-wing pundits. As Bruce Eder writes on AllMovie: “the story takes place against a backdrop of mounting government secrecy, deeper than anything seen in England since the war, and comments on the ways that democratic governments increasingly felt compelled to act amidst the Cold War and the Red Scare.” In the beginning of the film Quatermass is stonewalled by the government, trying to get his lunar project off the ground, only to find out later that it has already been realised in secrecy on Earth. Everywhere he turns to get information about the facility at Winnerdon Flats, he is met with ill-disguised cover stories, lies and and secrets, and it turns out anyone who tries to find out the truth end up either dead or brainwashed. To his horror, he finds that the conspiracy reaches the highest levels of government.

I think one of the main problems I have with the film is that I can’t quite make out which side of the fence Kneale and Guest are on. This didn’t bother be as much in Invasions of the Body Snatchers, a film which dealt more with the general atmosphere of Cold War America. However, I feel that Kneale is is making a specific point with Quatermass 2, and that I can’t quite put my finger on what his point is. As Richard Scheib writes on Moria: “I am not fully sure what Nigel Kneale’s underlying fear is here – the sinister power of government bureaucracy or of new industries like nuclear power gaining an ominous foothold into the British public – but the film certainly looms with an apprehension about its power and implacability.”

The acting is, as is often the case in British films, good. Donlevy’s range was extremely limited, and he struggles in the beginning of the movie, but comes into his own around halfway through. If he was intoxicated on set, it doesn’t show in the final product. Johnny Longden has the thankless task of taking over the role of Inspector Lomax from Jack Warren (who was unavailable for the film), but he easily makes it his own. He plays Quatermass’ confidante with a greater seriousness than Warren, which is welcome in this film, which instead has its comic relief in journalist Jimmy Hall. Hall is played by Hammer stalwart Sidney James, more accustomed to playing heavies, and he brings both charm and energy to the role. Despite providing some humour, his character also has its heroic moment, and his death becomes a dramatic highlight of the film, a sort of catalyst for refocusing the energy of the story, which up to that point is a bit scattered. We have seen the aliens possess and abduct people before, but this is the first time they commit cold-blooded murder, and it is a bit of a shock. Tom Chatto also brings a fresh energy, as the driven and idealistic MP determined to get to the bottom of the mystery. His death, although accidental, is another one that brings a sense of urgency to the proceedings. Vera Day, as the chirpy, air-headed barmaid who gets infected by the aliens, brings some lightness and fun to the proceedings, as well as some female beauty for the benefit of the male audience.

Reception & Legacy

Quatermass 2 was the first Hammer film for which the studio pre-sold the distribution rights to the US, which soon became their standard practice. While the first film had been successful in the States, that one had been released as The Creeping Unknown, so there was no point in releasing the second one under its original title. The movie was distributed by United Artists, and re-titled Enemy from Space, a descriptive if generic title. Like its predecessor, Quatermass 2 was very succesful at the box office both in the UK and abroad, however, it was eclipsed by Hammer’s own film, released around the same time, The Curse of Frankenstein (review). With the worldwide success of the monster revamp in colour, Hammer swiftly latched on to the possibilities of re-inventing the old, classic horror characters, quickly digging out both Dracula and the Mummy from the moth balls. This meant that while Nigel Kneale produced a third Quatermass series in 1959, Quatermass and the Pit, generally thought of as the best work of his career, Hammer passed on the opportunity to make a third Quatermass film. It wasn’t until the monster gallery was getting saturated after several Frankenstein and Dracula sequels that the studio returned to Quatermass in 1967.

Quatermass 2 premiered in May 1957 in the UK, where it was often screened alongside Roger Vadim‘s And God Created Woman, Brigitte Bardot’s breakthrough film — a somewhat unlikely pairing, perhaps. It premiered in the US at the end of September and was distributed in most of the country in October, just after the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik. With a US title like Enemy from Space, American reviewers were not above making references.

As usual, I have had problems finding British reviews, but accorcing to Wikipedia Campbell Dixon in The Daily Telegraph found the film “all good grisly fun, if this is the sort of thing you enjoy”. The reviewer in The Times remarked that “the writer of the original story, Mr Nigel Kneale, and the director, Mr Val Guest, between them keep things moving at the right speed, without digressions. The film has an air of respect for the issues touched on, and this impression is confirmed by the acting generally”. On the other hand, Jympson Harman of the London Evening News wrote: “Science-fiction hokum can be convincing, exciting or just plain laughable. Quatermass II fails on all these scores, I am afraid”.

The Los Angeles Times called the film “one of the half-dozen or so halfway decent science-fiction films of the season”, and said that Guest extracts “a generous amount of suspense” from Neale’s script. On the other hand, the Los Angeles Mirror opined that the film is “hampered by a muddled script”. The critic ended his report with: “the beast doesn’t get very far, leaving one of Donlevy’s baffled colleagues to mutter: ‘How am I going to report this?’ Funny thing, that’s what was worrying me.”

Neither was the US trade press impressed. Variety called it a “lesser entry in its field”, and continued: Val Guest’s direction is as uncertain as script […], with the result that all characters are stodgy”. Likewise, Harrison’s Reports said that “those who follow this sort of hokum” would find the film satisfying, but “Those who have some regard for story value, however, will find it disappointing, for, after building up interest in the proceedings, the story ends without clarification of its mystifying angles”. Motion Picture Daily also thought “the screenplay lacks cohesion and clarity”.

However, Phil Hardy in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Movies is one of those who thinks Quatermass 2 is “the bleakest and best of the trilogy”, and notes that “although the film has a conventional happy ending, its consiratorial edge remains”. According to Hardy, “With The Damned (1961), this is the hightpoint of the British Science Fiction film”. Film historian Bill Warren also calls it “one of the best science fiction films of the 1950s”. According to Warren, “the story idea is more involving, the production is livelier, and the story unfolds more eventfully”, than in The Quatermass Xperiment.

Today, Quatermass 2 has a 6.8/10 audience rating on IMDb, a 3.3/5 rating Letterboxd, and a 6.5/10 critic consensus on Rotten Tomatoes. AllMovie gives it a full 4.5/5 stars, with Bruce Eder writing: “The movie is often compared to Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers, […] but it goes deeper than that: the alien invasion of England, village by village, is depicted in grim enough terms, but Kneale and Guest focus on the ways that the invaders appropriate Cold War secrecy to their own ends, turning the government’s policies against the country and the people. In that sense, Quatermass 2 has nearly as much in common with All the President’s Men as with Invasion of the Body Snatchers. As in Alan J. Pakula’s dramatization of the fall of Richard Nixon, the heroes are men who dare to speak up.”

Many modern critics hold the film in very high regard, one of them is Glenn Erickson at DVD Savant, who says the film “took his head off”, as he “wasn’t prepared for the rich experience” provided by the film. Another one is Mark Cole at Rivets on the Poster, who says: “Quatermass 2 is one of the best SF films of the era — and easily better than The Quatermass Xperiment, which reduced Nigel Kneale’s unique original to a more or less routine monster movie”. David Pririe in his classic book A Heritage of Horror: The English Gothic Cinema 1946 – 1972 also hold the second film in the trilogy as the best, as do the authors of the The Aurum/Overlook Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction.

Others aren’t as ecstatic. Richard Scheib at Moria gives it “only” 3/5 stars, writing: “Finally seeing the film, it seems somewhat the lesser of what its reputation holds”. He continues: “ Quatermass 2 is much more of a prosaic film than The Quatermass Xperiment. The scenes with the alien conspiracy are muted […] There is not the sense of dehumanisation, of the familiar being abruptly alienated that we get in these other films.” And at Fantasic Movie Musings and Ramblings, Dave Sindelar writes: “This is the second of the three Quatermass movies made by Hammer. Even though I have a slight preference for the other two, this is far from a disappointment.”

Reportedly, Quatermass 2 has the distinction of being the first sequel in cinema history which has the number 2 in the title.

Cast & Crew

Writer Nigel Kneale initially educted himself as a lawyer, but but soon left the profession behind and started studying acting in the mid-40’s, while also beginning as a radio actor, reading some of his own short stories on the air. After having finished his studies, he published a story collection, which won the Somerset Maugham award, and encouraged in his writing, he left his short and uneventful acting career behind. He became a staff TV writer at the BBC in 1951, and graduated to the head of the TV drama writing department in 1952, where he struck up a fruitful companionship with fellow writer and director Rudolph Cartier.

In Europe, most countries had a single, often state-owned TV company that sort of could do whatever they pleased, and often simply filled the managerial posts with radio people. This meant much of early European TV was simply radio with pictures, and that was exactly the way Kneale and Cartier felt about the BBC. Especially the drama productions were often little more than filmed stage plays.

So when Kneale was called in to write six half-hour episodes of a new series to fill in gaps in the programming, he saw his chance to create something new and innovative, that would push the medium of TV further. Although never a big science fiction fan, Kneale loved horror stories and was fascinated by science, and when you combine these, you almost inevitably get sci-fi. Kneale was also an avid cinema-goer and was especially inspired by what he had seen been done in American films. Latching on to current events and the American SF trend, the result was The Quatermass Experiment. The show catapulted Kneale to fame, making him one of the most popular TV writers of his time. It also led to a second Quatermass series, Quatermass II (1955).

Nigel Kneale left BBC after his contract ran out in 1957, and immediately adapted the second series into a screenplay for Hammer, becoming Quatermass 2 (1957). 1957 was also the year he wrote the screenplay for The Abominable Snowman for the studio that really hit its stride with The Curse of Frankenstein – also in 1957 (review). Kneale wrote a third series for BBC as a freelancer, Quatermass and the Pit, in 1959, and like the previous shows it was directed by Cartier. This time he had a markedly bigger budget of one million pounds to make the series, and it is considered by many as the best of the three. Again Kneale wrote a film adaptation for Hammer, but the movie version of Quatermass and the Pit wasn’t released until 1967. Quatermass received a fourth and final series on the commercial channel ITV in 1979, again written by Kneale.

But Kneale and Cartier weren’t quite done shocking the fifties audiences yet. Encouraged by The Quatermass Experiment, they went to work on a two-hour TV film, released within the confines of BBC Sunday-Night Theatre, an adaptation of George Orwell’s Ninenteen Eighty-Four. The BBC received hundreds of complaints from viewers that thought the episode was gruesome and hideous and unfit for TV, and there was even a question filed in the Parliament about it. BBC even considered cancelling the second broadcast of it. But then word came from Buckingham Palace that Queen Elizabeth had watched it, liked it very much, and couldn’t wait for the second broadcast. With that, the matter was settled.

Nigel Kneale specialised in writing horror scripts, well-remembered for penning the six hour-long episodes for the mini-series Beasts (1976), but despite his outspoken dislike for sci-fi, he couldn’t stay away from the genre. He also adapted H.G. Wells’ book into First Men in the Moon (1964), wrote the TV movie The Stone Tapes (1972), probably the first film in which scientists use modern technology and computers to catch a ghost, and wrote the comedy sci-fi TV series Kinvig (1981). Approached by producer John Carpenter, he agreed to write a script for Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982). However, he disliked the re-writes by the director so much that he had his name removed from the film. He was also approached to write scripts for The Twilight Zone and The X-Files, but declined.

Director Val Guest began his career as a stage and movie actor in the late 20’s and 30’s, without any greater success, and then had a short stint as the London correspondent for the Hollywood Reporter. It was during this time that director Marcel Varner got miffed with his criticism, and jokingly challenged Guest to write a better script himself if he could. So in 1935 he wrote the comedy No Monkey Business, which Varner directed. The film won no accolades, but turned out decent enough that Guest kept at it, and wrote or co-wrote over 30 scripts between 1935 and 1943 – 18 of them for Varner, who apparently found that Guest was indeed better than his previous writers. After some uncredited assisting directorial work, he got the chance to direct his first movie in 1943, Miss London Ltd., which was a fairly well received comedy quota quickie for Gainsborough Pictures. He continued to direct nearly 20 comedies for Gainsborough between 1943 and 1955, as well as a few for Hammer.

After Quatermass 2, Guest continued to dabble in a number of different genres, and made a few more films for Hammer. However, the Quatermass movies were the only science fictions films he made for the studio, unless you count The Abominable Snowman (1957) or the cult film When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) as sci-fi. The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961) is often considered Guest’s best movie. He wrote the film, concerning the build-up to a nuclear holocaust, together with Wolf Mankowitz, and the two were awarded with a BAFTA for best British screenplay in 1962. Even if the climate change depicted in the movie is nuclear-caused, it seems eerily prescient today. In 1970 Guest was attached to direct the bizarre science fiction musical comedy Toomorrow, a vehicle to promote a new TV pop band helmed by Olivia Newton-John, which the producers hoped would be the new The Monkees. “Terrible”, was what Newton-John called it. That same year he also directed the tacky caveman film When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth, best remembered for Jim Danforth’s stop motion animation and Italian-American starlet Victoria Vetri’s skimpy outfit. Vetri took up the battle with Raquel Welch over which cave girl could wear the least clothes without actually being nude. In an interview with Tom Weaver, Guest calls the movie “awful, awful, awful”, and says Vetri, a centrefold, was a “bimbo” and a “nitwit”.

Guest is also known as one of the five directors who took on the impossible task of trying to direct the train wreck that was Casino Royale (1967). In 1971 he co-wrote and directed the heist movie Killer Force, best remembered for its amazing cast, including Telly Savalas, Peter Fonda, Christopher Lee and Maud Adams. He worked primarily in TV in the late seventies and eighties, and retired in 1984, after directed three episodes of Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense. Guest passed away in 2006.

Brian Donlevy was a celebrated character and lead actor in the forties, after he had been nominated for an Oscar for his role in Beau Geste (1939). He played the title role in The Great McGinty (1940). He had leads or second leads in John Farrow’s Wake Island (1942), the noir classic The Glass Key (1942), Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die! (1943) and John Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947), among others. From 1949 to 1953 he starred in the radio serial Dangerous Assignment, which was turned into a TV series in 1952, but it aired only for one season. This was sort of the last hurrah for the ageing actor, and in the early fifties film roles were sparse, and he got attached to Robert Lippert’s small production company (a front for 20th Century Fox), which amassed a roster of star actors down on their luck. Drinking was one of the reasons for Donlevy’s fall from grace in Hollywood.

Brian Donlevy went on to star in Quatermass 2, but wasn’t called back for Quatermass and the Pit. He starred in two other science fiction movies; he played the lead in Curse of the Fly (1965), and one of the leads in Gammera the Invincible (1966), the re-shot and Americanised version of Daikaiju Gamera (1965). In Denis Meikle’s book A History of Horrors: The Rise and the Fall of the House of Hammer, Val Guest doesn’t have anything bad to say about Donlevy, despite his drinking problem: ”He was a great guy. He used to like his drink, however, so by after lunch he would come to me and say, ‘Give me a break-down of the story so far. Where have I been just before this scene?’ We used to feed him black coffee all morning but then we found out he was lacing it. But he was a very professional actor and very easy to work with.” Donlevy had created for himself a carefully managed image. Although quite dashing in his own right in his younger years, he very early started using a girdle to give him the triangle-shaped torso of an athlete. Every time he came on set, his ritual started with putting in his false teeth, then the girdle, platform shoes to make him seem taller, and lastly a hair-piece to hide his balding head. One of the few mishaps on Quatermass 2, apparently, happened in one of the last scenes, in which the alien facility blows up, sending a shockwave over the protagonists. The heavy fans used in the scene dislogded Donlevy’s toupee, sending the crew scrambling for it across the hillside.

John Longden, playing Inspector Lomax, was a leading man of early British talkies, before becoming a dependable supportinh actor. A favourite of Alfred Hitchcock’s, who appeared in 5 of Hitchcock’s films. He had a supporting role in the British-German sf film Human Factor (1964). Sidney “Sid” James, born in Johannesburg, was a respected and in-demand character actor specialising in gruff, sometimes villanous roles, often in comedies. He rose to stardom in the Carry On comedies, starting 1960, in which he made close to 20 apperances up until his death in 1976.

Bryan Forbes, who plays assistant Marsh, was another well-respected character actor, who also dabbled in screenwriting. Although he kept appearing in movies throughout his career, in 1959 started focusing more on the production side, setting up an independent company alongside frequent collaborator Richard Attenborough, and in 1961 made his debut as a director. That same year Forbes was nominated for an Oscar and a BAFTA for his writing on The Angry Silence. His comedy The League of Gentlemen was also nominated for a screenplay BAFTA the same year. In 1962 his movie Whistle Down the Wind was nominated for a Best Film BAFTA. He won an Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Foreign Film in 1965 for Seance on a Wet Afternoon, and in 1967 his perhaps best-regarded film, The Whisperers, was nominated for the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. However, his most lasting legacy may be the direction of the creepy middle-class science fiction satire The Stepford Wives (1975). In the 70’s Forbes worked as the managing director of Elstree Studios.

Vera Day (apperently her real name) plays the only featured female role in the film – a crucial, if small one. Day was a hair model who got hired as a stage showgirl in the mid-50’s after auditioning in the smallest bikini she could find. She was spotted by Val Guest at one of the shows, and was brought into the film business. Here she made a modest career as a blonde bombshell in both serious and comedic films. She is perhaps best remembered for appearing in Quatermass 2 (1957), the crime drama Hell Drivers (1957), the horror film Womaneater (a rare lead, 1958, review), the Boris Karloff vehicle Grip of the Strangler (1958) and the crime comedy Too Many Crooks (1959). Day dropped out of acting in the early 60’s but made a surprise return in 1998 in Guy Ritchie’s likewise surpsise hit movie Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. She had a small but memorable role as a croupier explaining the rules of a poker game, and said in an interview she was extremely happy to have “the only female role in the film with lines and her clothes on”. She accepted occasional roles in the years to come, most notably in the straight-to-video release The Riddle (2007). Her latest film appearance was in the short film Bad Friday in 2017.

Percy Herbert went on to become a recognisable supporting actor in both UK and US films, especially for his roles as soldiers in Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and The Guns of Navarone (1961), and as a seaman in Mutiny on the Bounty (1962). He also held a co-lead as Sakana in Hammer’s legendary remake of One Million, B.C. (1966), starring Raquel Welsh. He appeared in the SF films Timeslip (1955, review). Quatermass 2 (1957), Mysterious Island (1961), Night of the Big Heat (1967) and Doomwatch (1972).

Michael Ripper is a Hammer legend. He switched between stage work and small roles in film from 1936 to 1952, when a thyroid infection put an end to his stage career, and he switched to film and TV, which required less volume and projection. He made his Hammer debut in 1956 with X the Unknown, and subsequently appeared in a whopping 35 Hammer movies, often in small but quirky and memorable roles, with a humorous twist. He is particularly memorable in three of his collaborations with director John Gilling, with two large supporting roles as the zombified Sergeant Smith in Plague of the Zombies (1966), in a rare heroic co-lead in The Reptile (1966) and as the sympathetic manservant to the obnoxious John Phillips in The Mummy’s Shroud (1967). After his work at Hammer, Ripper mainly appeared as a guest star on TV – often in big and successful shows, and kept acting until the mid-90’s. All in all, he appeared in small roles in nine SF movies.

John Stuart was another Hammer staple, and appeared in a are 1948 TV version of Karel Capek’s R.U.R., as well as in Four-Sided Triangle (1953, review), Raiders of the River (1956), Quatermass 2 (1957), The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958, review), Blood of the Vampire (1958), Village of the Damned (1960) and Superman (1978).

Composer James Bernard created the musical backdrop that we so readily associate with the Hammer horrors, and he almost exclusively worked for Hammer during his career. Oddly enough, his only real accolade was an Oscar for writing, as he co-wrote the story for the 1950 thriller Seven Days to Noon. Editor James Needs was yet another part of the Hammer family, seemimgly editing every Hammer horror film from 1955 to 1968. Production designer Bernard Robinson falls into the same category, praised by Val Guest for his ability to whip up extravagant sets for next to no money. Makeup artist Philip Leakey, however, didn’t stay on with Hammer past 1958, and went on to work on more “traditional” films. Among the special effects people in the crew we find Frank George, who went on to work on several James Bond movies, Bill Warrington, who won an Oscar for his work on The Guns of Navarone and not least Brian Johnson, a key special effects worker on the Alien and Star Wars franchises.

Janne Wass

Quatermass 2. 1957, UK. Directed by Val Guest. Written by Nigel Kneale & Val Guest. Starring: Brian Donlevy, John Longden, Sidney James, Bryan Forbes, Tom Chatto, William Franklyn, Vera Day, Charles Lloyd Pack, John Van Eyssen, Percy Herbert, Michael Ripper, John Rae. Music: James Bernard. Cinematography: Gerand Gibbs. Editing: James Needs. Art direction: Bernard Robinson. Sound editor: Alfred Cox. Special effects: Frank George, Henry Harris, Bill Warrington, Brian Johnson. Visual effects: Les Bowie. Produced by Anthony Hinds for Hammer.

Leave a comment